Introduction

In June of 2016, the Government of Canada passed federal legislation allowing eligible adults in Canada to seek medical assistance in dying (MAID) (Government of Canada, 2016). Eligibility criteria included individuals who have health services funded by a government in Canada, are aged 18 or older, are able to make a voluntary request without external pressure, have the capacity to give informed consent, and have a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” as per the law (Government of Canada, 2016; Reel, Reference Reel2018). During the course of the study, for a medical condition to be considered grievous and irremediable, the person must have had a serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability, been in an advanced state of decline in capability, and been experiencing intolerable physical or mental suffering that cannot be relieved under conditions acceptable to them, and a natural death that was “reasonably foreseeable” (Government of Canada, 2016; Reel, Reference Reel2018). Prior to engaging in MAID, individuals must be deemed eligible by two MAID assessors, wait a 10-day reflection period, and provide informed consent twice, once prior to the 10-day waiting period and again right before the service (Government of Canada, 2016; Reel, Reference Reel2018). Some eligibility criteria and procedural safeguards were changed in March 2021 when the law was amended, after all data collection (Government of Canada, 2021).

Family members often play an integral role in the provision of care for their loved ones. Family caregiving is defined as an unpaid role adopted by partners, family members, or friends, usually taken on in addition to other personal roles such as full-time employment (Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2013; Battams, Reference Battams2016). In 2012, approximately one-third of Canadians reported providing care to a family member or friend with a long-term health condition, disability, or aging need at one point in their lives (Battams, Reference Battams2017). Additionally, family caregiving yields benefits to Canada's healthcare system as it contributes over $25 billion (2,006 dollars) in unpaid labor by reducing the cost of health services and institutionalization (Hollander et al., Reference Hollander, Lui and Chappell2009; Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2013; Battams, Reference Battams2017; Healthcare, 2018; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, Nissim and An2021).

Family caregivers hold different perspectives regarding assisted dying. A prospective cohort study completed between 1996 and 1997 in the USA found that family caregivers were in favor of assisted dying if their terminally ill care recipient was in pain, their caregiver role interfered too much with their personal life, or if their care recipient felt like they were a burden (Jacques and Hasselkus, Reference Jacques and Hasselkus2004). Family caregivers who were religious, African American, and those with strong social supports were less in favor of assisted dying. A qualitative study in Switzerland, where assisted dying is available, revealed family caregivers were conflicted with moral dilemmas when involved in the decision-making process (Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015). Most caregivers stated they feared blame and social stigma when supporting their loved one with this request; while most caregivers resolved these feelings through respect of the care recipient's autonomy, some remained conflicted with these issues years after the care recipient had died. A recent Canadian qualitative study conducted with family caregivers to individuals who sought MAID described their experiences as a “race to the end” (Thangarasa et al., Reference Thangarasa, Hales and Tong2021). The study captured caregivers’ experiences related to being a “co-runner,” “onlooker,” and “tending to the finish line.” Another recent Canadian study of family caregivers characterized the bereavement experience (Beuthin et al., Reference Beuthin, Bruce and Thompson2021). It highlights caregivers’ experiences related to certainty of a date and time for death, planning the death, and enacting MAID as a ceremony. These studies provided valuable insight into caregivers’ experiences with their involvement in MAID.

Existing research has not explored the experiences and needs of caregivers to specifically inform programs and services to support them in their important role. As Canada's MAID legislation varies from other countries, for example its eligibility criteria including an individual's “foreseeable natural death,” family caregiver experiences with MAID may vary greatly across the globe (Gamondi et al., Reference Gamondi, Pott and Forbes2015). Therefore, the objective of this qualitative study was to explore the experiences and support needs of family caregivers who are or who have provided care to individuals who are seeking or have sought MAID in Canada.

Methods

Study design

This study used a descriptive qualitative design (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000, Reference Sandelowski2010).

Participants

Canadian family members involved in the provision of care for their loved ones who were seeking or have sought MAID were recruited. Adults living in Canada, 18 years and older, assisting with a minimum of one activity of daily living or instrumental activity of daily living per week were included. Non-English-speaking individuals and individuals receiving monetary compensation for their care were excluded. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants through social media outlets, such as Twitter and Reddit, and various support organizations including ALS Society of Canada, the Canadian Cancer Society, and Dying with Dignity Canada. Snowball sampling was used to obtain additional participants.

Data collection

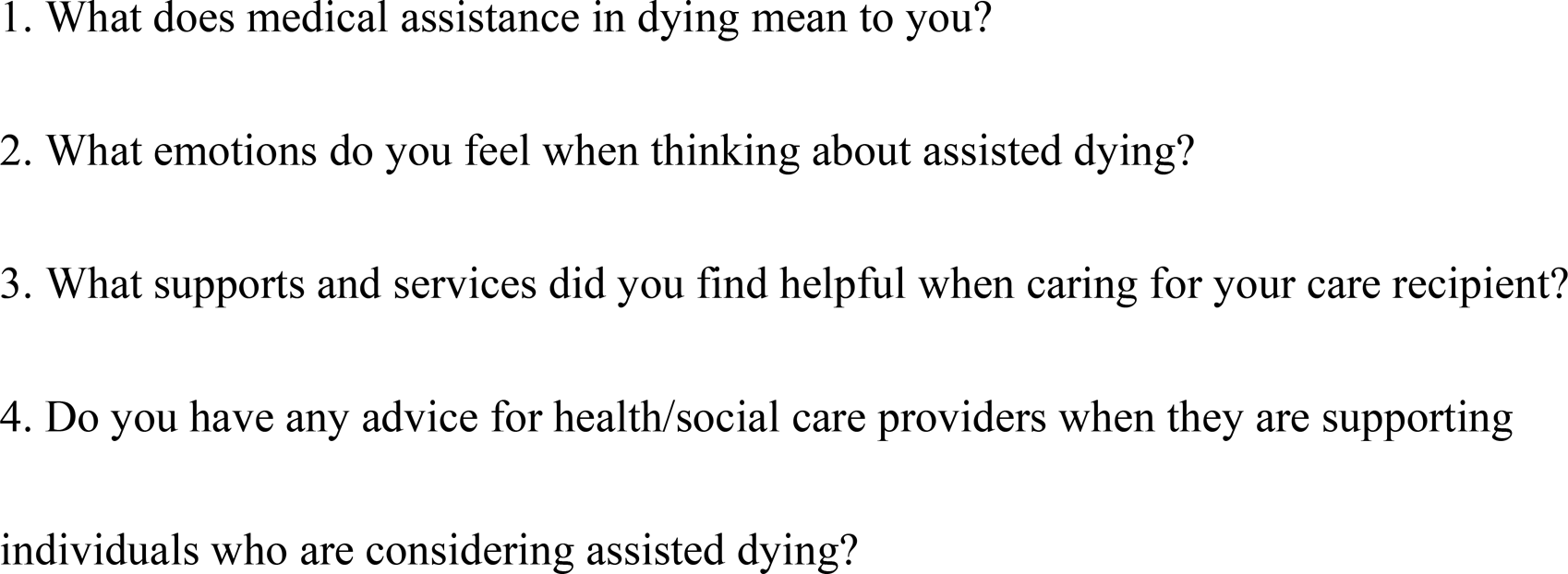

Data were collected between February 2018 and April 2020 using an online survey and in-depth telephone interviews. Consent forms outlining the nature and purpose of the study were included in the online survey or circulated electronically and signed prior to being interviewed. The telephone interviews adapted the questions that were included in the online survey (see Figure 1 for sample questions). Qualitative interviews allowed the participants to elaborate on their experiences, through prompting of open-ended questions (Merriam and Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified by researchers (Patton, Reference Patton2015; Merriam and Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016). Researchers wrote memos to capture initial ideas following each interview to aid in the exploration of the phenomena, and begin to extract meaning from the data (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Birks et al., Reference Birks, Chapman and Francis2008). Thematic saturation was achieved through the total collection of online surveys and interviews (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985).

Fig. 1. Sample online survey and interview questions.

Data analysis

Braun and Clark's Six Phases of Thematic Analysis were used to guide the organization, description, and interpretation of the in-depth telephone interviews and online surveys (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The computer software program, NVivo (Version 12) (NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software, 2012), was used to support the text-based analysis process (Hilal and Alabri, Reference Hilal and Alabri2013). Researchers individually immersed themselves within the data by actively reading through each transcript/survey response repeatedly to aid in identifying level one codes, which were defined and redefined throughout the analysis. Once the independent analyses were complete, the researchers completed level two coding by comparing and discussing findings to consolidate final themes.

Investigator triangulation and peer review by all authors were employed to ensure the credibility of the findings (Merriam and Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016). In addition to credibility, researchers contributed to self-reflexive journals weekly to minimize potential biases and assumptions related to the study context of MAID. This strategy further enhanced the transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the findings (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985; Carpenter and Hammel, Reference Carpenter, Hammel, Hammell, Carpenter and Dyck2000; Merriam and Tisdell, Reference Merriam and Tisdell2016).

Ethical approval

The institutional research ethics boards approved this study protocol.

Results

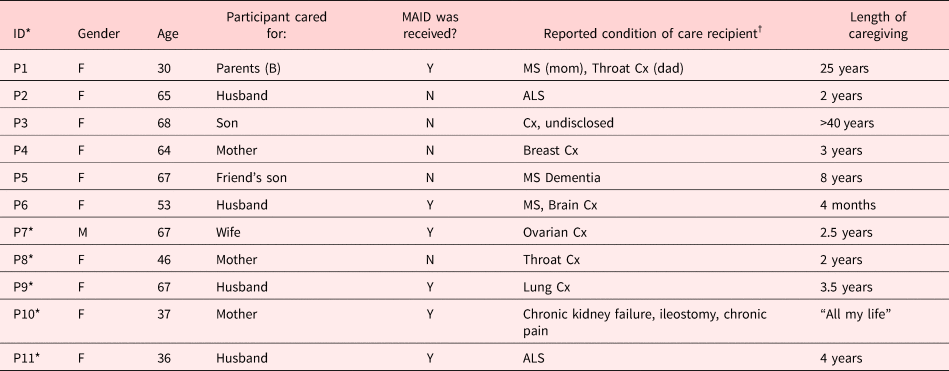

Data were collected from 11 participants, through six interviews approximately 1 h in length, and five online surveys. A summary of participant characteristics is presented in Table 1. Briefly, participants were female (n = 10), aged 30–68 years, caring for a spouse (n = 5), parent (n = 4), or son (n = 2), and 6 had experienced MAID. Three main themes were identified: the caregiver experience including roles and responsibilities and the impact of their role; the MAID experience including the process and their thoughts and feelings about MAID; and caregiver insight into supports and services viewed as valuable or needed for the MAID process.

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 11)

* represents data collected through an online survey in 2018.

†Cx: cancer.

The caregiving experience

Caregiver roles and responsibilities

Caregivers assume various roles and responsibilities including assisting with bowel and self-care activities, physical handling and positioning, supporting their care recipients’ engagement in social activities and vocational roles, and providing emotional support. Participants commonly expressed their role as a caregiver to be all-consuming: “I felt as though I was on call in some ways” [P1]. Several participants reported their role as a coordinator of care. One participant expressed she felt “sort of like a general contractor” [P4]. Caregivers also identified the provision of emotional support as a common role to fulfill: “My role was trying to be emotionally there” [P6].

Consequences and impacts of caregiver roles and responsibilities

Participants reported that their caregiver role greatly impacted their identity, engagement in personal activities, and their relationship with their care recipient. For example, one participant found it difficult to distinguish between their role as a caregiver and their role as a partner:

“So, then it became there I am, I'm the nursing aid and it grew from there. I don't think that's an uncommon factor and even over time our neurologist would say ‘stay the wife, don't become a caregiver’ and I don't think that's possible to separate … I just became the shrew in the pink housecoat.” [P2]

Additionally, the roles and responsibilities caregivers assume directly impact their ability to engage in meaningful activities related to career aspirations, leisure activities, and socialization. Participant 5 stated caregivers are “not able to take care of their own careers or passions” [P5]. Similarly, participant 11 expressed: “I always put their [care recipient's] needs and wants before my own” [P11].

Furthermore, participants expressed the quality of their relationship with their care recipient was impacted due to their caring roles and extensive responsibilities. This inevitably caused strain and “disconnect” [P2] in their relationship:

“It can be very hard to stay patient and kind when you're helping someone who's going through something that is slowly taking away their ability to be their own person. That brings up a lot of emotions in them and especially being such a close member of their family it can make things really tense sometimes.” [P1]

In contrast, another participant spoke about how their caring role brought them and their care recipient closer: “I think it makes you appreciate the person more, you know they are considering dying in the near future and you take that time to connect with them before they are gone” [P11].

The MAID experience

Logistical process

All participants expressed positive opinions about the legalization of MAID in Canada; however, many felt that there are “a lot of improvements that need to be made” [P1]. Participant 1 continued:

“I like that we chose not to make terminal illness a criteria. I think that the phrasing of ‘grievous and irremediable conditions’ is a fair bracket and the wording really covers the situation well and covers different categories of patients. But I also think that we leave a lot of people behind with those criteria.” [P1]

Most participants negatively viewed the mandatory 10-day reflection period as it is possible for a care recipient to be considered ineligible to receive MAID due to sudden fluctuations in one's capacity. Participants viewed this requirement of the legislation as “constrictive” [P3]. For one participant's wife in particular, “the 10-day cooling off period were the most cruel days of her life” [P7].

Participants expressed they were often the ones to initiate the MAID conversation rather than the healthcare practitioner (HCP) involved: “I was the one who brought it up at the hospital because we were given absolutely no choices, options, or hope” [P4]. Many expressed that they would have appreciated transparency from the medical staff regarding MAID as an option for their care recipients: “I think that they [caregiver and recipient] should be given the information. If they do not want to discuss it, leave it alone, but providing the information is important for them to have it” [P6].

Participants stated that the MAID experience was challenging to organize and required extensive planning in advance, such as funeral planning, and closing personal affairs (e.g., bank accounts and social security). One participant recounted the planning of their care recipient's funeral: “It was just very surreal, it was strange. It was like planning Christmas” [P6]. Additionally, another participant found it hard to “to predict and to see forward all these things we have to take care of” [P2].

Thoughts and feelings about MAID

Respect for one's autonomy was common: “I completely support it and it's extremely important to be able to give people that option in a dignified way, and respect them and not have a stigma associated with it” [P1]. In one case, MAID allowed a participant's wife “to have autonomy over her life … at a time she needed it most” [P7].

Caregivers also spoke to the importance of having empathy toward individuals who were contemplating or have chosen MAID: “Having lived through my wife's illness and death by MAID, I believe it allows me the empathy to relate to the decision process” [P7]. Participants were able to extend their empathy toward other individuals who may be considering MAID: “People shouldn't have to suffer horribly before they die if there's an alternative to ease their suffering – to make their passing a little easier on them and everyone else” [P6]. Additionally, caregivers reported feelings of compassion toward individuals in similar caring situations, “for the idea that someone else is going through that … that those people [family caregivers] need extra support that they aren't getting, so that's why I feel compassionate in that situation” [P1].

Many participants expressed that MAID gave their care recipients a sense of relief: “Relief from the indignities, the end to suffering whether it's pain or emotional” [P2]. One participant shared that, “if it had not been for MAID, my wife would have ended her life alone by her own hand and possibly earlier in her disease. Knowing this was her option, allowed time to reflect on a life that was well lived knowing the end would be a peaceful event” [P7].

Lastly, the option of MAID enabled caregivers and their care recipients an opportunity for closure: “We were able to have conversations that you always wish you could have with someone because we knew what was coming, so we were able to have those in time and I think there was a lot of closure on both ends” [P1]. Since MAID is a scheduled procedure, participants found they were able to focus on spending quality time during the last days with their loved ones: “It was wonderful knowing there was an option so that we could focus more on the remaining days together” [P7]. Other participants, however, found the remaining days to cause added stress: “I would be very anxious about making sure the last few days were really happy” [P8].

Caregiver supports and services

The third theme, access to supports and services, is integral to both the caregiver experience as well as the MAID experience and is not mutually exclusive. Caregivers discussed their limited insight into supports they found valuable and would have liked to receive.

Limited insight into supports needed

Caregivers acknowledge that they need a variety of supports to assist with their caring role, such that “it takes a village” [P2]. In some instances, however, caregivers were unable to identify the specific supports necessary to assist them:

I would be absolutely at my wit's end going ‘I need help I need help ‘and they [palliative care team] asked what do I need and I would go ‘I don't know this is your job, you tell me what I need' … How can I identify my needs right now, I need help [P2].

Valuable supports

Participants expressed counselling, support groups, and self-care activities were critical to adequately care for their family members. One participant engaged in grief-counseling services a year and a half prior to both her parents opting for MAID: “I knew what was coming and I continued after they passed as well, going in advance helped me to process what was going on” [P1]. Furthermore, many participants reported that peer support groups fostered a sense of belonging, regardless of the groups taking place in person or virtually: “I think that's really important in people feeling that they are not isolated … That they have support from other people who understand what they are talking about” [P5]. Support groups offer caregivers the opportunity to connect, “through conversation and friendship” [P10] with like-minded individuals who have encountered similar experiences.

Desired supports

Advance care planning was identified as a support that could have assisted with the administrative aspects of MAID (e.g., accessing MAID, liaising with stakeholders, and processing appropriate paperwork): “I think the biggest area that we could have used help is having assistance to go through that process [MAID] during a time that is already highly emotional and confusing. I think that's a service that's lacking right now” [P1]. Furthermore, participants commonly identified the MAID process as highly emotional and suggested a MAID or “death” coach as a potential support: “That's a role that could be taken on in supporting the patient and the family while the MAID process is happening” [P5].

Discussion

This study added to the small body of research examining family caregivers’ perspectives on assisted dying. It explored the experiences and needs of family caregivers who have provided care to individuals seeking or who have sought MAID. The results demonstrated the participants’ roles as caregivers (e.g., assisting with self-care practices, physical handling, and the provision of emotional support) had greatly impacted their personal identity, ability to engage in meaningful activities, and their relationship with their care recipient. This first theme is common to other caregiving situations, but the subsequent themes were more unique to MAID. The MAID legislation influenced the trajectory of their caring roles and experiences as a caregiver from initiating the conversation about MAID to participating in extensive care planning. Access to various services such as counseling, peer support groups, as well as MAID or “death” coaches were identified as necessary to improve caregivers’ MAID experience. There are aspects of the process that can be modified, such as amendments to the legislation, communication improvements among stakeholders, and enhancing supports for family caregivers.

All participants positively reflected upon the legalization of MAID in Canada; however, each expressed the need for improvements. From the caregiver's perspective, the legislation is seen as partly restrictive and inconsiderate of the emotional aspect for both the care recipient and the caregiver. Caregivers directly felt the negative impact of the 10-day reflection period, leading to additional undue stress for both parties. The uncertainty of maintaining capacity during this waiting period presented a barrier for family caregivers, cultivating concern around the revocation of their care recipients’ eligibility for a dignified death. Another Canadian study similarly highlights this concern, labeling this requirement as highly negative and anxiety-provoking for family caregivers (Hales et al., Reference Hales, Bean and Isenberg-Grzeda2019). Since the completion of this study, amendments to the law have introduced two procedural streams — depending on whether natural death is reasonably foreseeable. Where natural death is reasonably foreseeable, no reflection period is required and a waiver of the final consent is possible. Where natural death is not reasonably foreseeable, a 90-day assessment period is required (Government of Canada, 2021). These changes should improve the emotional experience for some caregivers, but more research is needed to explore the impact of all the changes.

Another challenge experienced by the caregivers was the limited communication within the healthcare system about MAID as an end-of-life option. All family caregivers reported the MAID discussion was never initiated by healthcare professionals and felt that the onus was placed on them to explore MAID. Professional standards of practice across Canada suggest that a request for MAID is initiated by a patient request; however, it does not prohibit healthcare professionals from initiating the MAID conversation (College of Physicians & Surgeons of Nova Scotia, 2017; College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta, 2018; College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario, 2018; British Columbia College of Nursing Professionals, 2020). Despite the numerous professional practice resources available to assist healthcare professionals when navigating the MAID process, the literature suggests they may shy away from such conversations due to legal jargon regarding the “counseling” of suicide, as this is deemed a criminal offense in Canada (Seccareccia et al., Reference Seccareccia, Ying and Isenberg-Grzeda2018); religious beliefs (Bator et al., Reference Bator, Philpott and Costa2017; Beuthin et al., Reference Beuthin, Bruce and Scaia2018); ambiguous care pathways (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Goodridge and Harrison2020); and lack of knowledge about MAID (Fujioka et al., Reference Fujioka, Mirza and Klinger2019; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Goodridge and Harrison2020). Furthermore, the literature emphasizes the importance of compassionate listening when providing information about MAID to patients and their caregivers (Bushinski and Cummings, Reference Bushinski and Cummings2007; Gauthier, Reference Gauthier2008; Beuthin et al., Reference Beuthin, Bruce and Scaia2018); one study highlighted medical students’ desire for MAID-specific communication skills training (Bator et al., Reference Bator, Philpott and Costa2017). Interpersonal communication training about MAID conversations will be imperative for healthcare professionals to lessen the distress, anxiety, and stigma both parties experience when initiating these conversations. This may be an area where MAID-specific coaches can be introduced (e.g., allied health professionals) to normalize the MAID process as an available end-of-life option. This may also bridge the communication gap by helping individuals suffering from grievous and irremediable conditions to initially receive the necessary information to make an informed decision.

This study has added to the literature on the value of various supports for caregivers within a MAID-specific context, including caregivers’ engagement in self-care practices, MAID-specific peer support groups, and grief-counseling in advance. Yet, as seen through this study, there was not one support or service that seemed to be helpful across all caregivers, suggesting caregiver support does not warrant a universal approach. This coincides with the existing literature on palliative care, which “found that interventions aimed at individual caregivers were more effective in improving caregiver well-being” (Reinhard et al., Reference Reinhard, Given, Petlick and Hughes2008). These findings highlight the importance of family-centered practice within healthcare regardless of the practice context, which aims to create a partnership between the patient, family, and healthcare professionals (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Chaboyer and Burmeister2009). This holistic approach allows for families to be included in the care, subsequently acknowledging the distinctive needs of all stakeholders involved (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Chaboyer and Burmeister2009). Employment of this approach in the context of MAID will therefore allow the unmet needs of family caregivers to be addressed. By providing adequate and appropriate support, caregivers will be better equipped to provide the best possible support for their loved ones.

Limitations

Despite recruitment efforts, the lack of gender diversity, exclusion of non-English speakers, and small sample size may limit the transferability of study results. Additionally, 5 of 11 caregiver perspectives were collected via an online survey, limiting exploration of topics and probing for additional detail. All study participants were in favor of MAID presenting a possible bias, further limiting the transferability to other individuals and perspectives.

Conclusion

This qualitative study is among few within the literature and provided valuable insight into the family caregiver perspective regarding MAID. Family caregivers play an integral role in supporting their care recipients throughout the complex MAID process. As a result, findings from this study may guide the development of best practice resources and guidelines to better support the various healthcare professionals involved in this process. These resources may improve healthcare professionals’ competency in this context by aiding in the understanding of the needs of family caregivers. The aim is to ensure caregivers feel well supported when involved in MAID. Future studies should explore ways in which Canada's healthcare systems can incorporate the family caregiver perspective within practice to ensure holistic family-centered care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the organizations that assisted with recruitment and the caregivers for sharing their experiences.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.