Researchers and aid administrators have observed that the rise of populist radical right (PRR) parties has pressured change in government policies not only on the issues of immigration and integration but also regarding the reduction of foreign aid (Jakupec and Kelly, Reference Jakupec and Kelly2019; Thier and Alexander, Reference Thier and Alexander2019).Footnote 1 Their observations align with PRR parties’ manifestos that critically discuss the aid–immigration nexus. In Austria, the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) states that it ‘rejects traditional development aid as a failed model and urges efficient development cooperation as ‘helping people to help themselves.’’ In Switzerland, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) states that ‘with a new direction of development cooperation, the SVP particularly welcomes the intended stronger link with migration issues…and criticizes that the federal government still wants to put too much tax money into development aid. It calls for one billion of this money to be used to secure pensions and thus for the people in Switzerland’ (Swiss People’s Party, 2019). In the Netherlands, the Party for Freedom (PVV) states ‘no more money for development aid, wind power, art, innovation, and broadcasting. Immigration should stop for people from Islamic countries…, instead of financing the entire world and people we don’t want here, we’ll spend the money on ordinary Dutch citizens’ (Party for Freedom, 2019).

Despite these hostile words toward aid and immigration, the PRR’s aid-reducing impact is far from certain, given that studies show mixed findings on the significance and direction of PRR influence in aid policy (Hammerschmidt et al., Reference Hammerschmidt, Meyer and Pintsch2022; Hackenesch et al., Reference Hackenesch, Högl, Öhler and Burni2022). This may be because they neither modeled immigrant inflows as an intervening variable nor employed a bilateral framework capable of ascertaining crucial properties in both donor and recipient countries that affect the PRR’s political strategies and aid allocation. Nevertheless, the parties’ aid-reducing pressure seems consistent with their ideational profiles of nativism and anti-establishment that motivate them to prioritize ordinary citizens at home and condemn the establishment’s aid policy that ignores the people’s well-being and fails to control immigration. By engaging in these ideational profiles, radical right movements complicate a political space in donor governments’ policymaking through electoral pressure and participation in governing coalitions with mainstream parties (Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; de Lange, Reference De Lange2012; Lutz, Reference Lutz2019; Schain, Reference Schain2006).

Therefore, this study analyzes the PRR’s influence on aid policy via the electoral and coalitional pathways by employing a bilateral framework. It considers immigrant inflows as a lever and mainstream parties’ ideological positions as a control, because PRR parties often partner with mainstream- or center-right parties that have similar ideological and policy orientations despite different views toward constitutional democracy, the self-regulating power of the market, and a non-intervening government attitude (Greene and Licht, Reference Greene and Licht2018; Tingley, Reference Tingley2010). The bilateral framework enables analysis of how donor governments alter aid allocation to specific recipient countries, conditional upon the flows of immigration therefrom. Further, this helps ascertain the recipients’ sociocultural characteristics and donors’ institutional arrangements affecting PRR political strategies and thus aid allocation.

This study examines panel data to estimate the PRR’s effect on bilateral aid allocation by 17 parliamentary democracies in Western Europe. It focuses on Western European democracies because they have robust constitutional structures that are consistent with the central premise of the coalition theory considered in the study (Meguid, Reference Meguid2008; Twist, Reference Twist2019). By contrast, emerging democracies in Eastern Europe often have fragile constitutional structures and limited experiences in aid provision. In several East European countries, PRR parties have captured many parliamentary seats and executive control through historical and Eurosceptic narratives that differ from the ideational profiles of their Western European counterparts (Petrović et al., Reference Petrović, Raos and Fila2022; Santana et al., Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020). Their electoral successes have rendered it unnecessary to gain mainstream parties’ partnership or accommodation for influence. Thus, PRR parties in Eastern Europe are incompatible with the theoretical premise and are not considered here.

This study demonstrates, through extensive data analysis, that PRR parties exert significant aid-reducing pressure toward recipient countries that send substantial numbers of immigrants to the donor country, by either participating in or providing support for government coalitions, given that mainstream parties’ ideological positions and other things are equal. The depth of PRR aid-reducing pressure is correlated with the immigrant inflow from the recipients. It further shows that such pressure is more likely to occur in conjunction with donors’ weak pluralistic institutions and immigrant-sending recipients’ heterogeneous sociocultural characteristics than otherwise.

The finding of punitive aid reduction has two important implications for political scientists. First, the PRR’s influence over aid contradicts conventional wisdom in the literature, which suggests that major determinants of aid allocation are foreign policy objectives, mainstream parties’ ideologies, and welfare norms in donor countries (Morgenthau, Reference Morgenthau1962; Tingley, Reference Tingley2010; Thérien and Noël, Reference Thérien and Noël2000; Lumsdaine, Reference Lumsdaine1993). PRR influence over aid is a significant turning point in populist politics because aid policy is essentially driven by the establishment tapping into the public’s moral and instrumental concerns with promises about what aid will achieve regarding diplomacy, international distributive justice, and immigration. Second, targeted aid reduction can be considered a punishment to the recipients who have become a source of threat to the donor’s ordinary citizens through emigration control failures. Such politics of punishment, which has been observed in the penal policies of several liberal democracies (Pratt, Reference Pratt2007; Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stalans, Hough and Indermaur2003), now appears in aid policy. Through coalitional partnership with mainstream parties, the PRR engages in the politics of punishment specifically toward immigrant-sending recipients with sociocultural characteristics different from the donor’s ordinary citizens, by exploiting the establishment’s immigration control failure under weak pluralistic institutions.

The remainder of this paper is structured into four sections. The next section presents a literature review on the politics of aid and identifies the determinants of aid. The second section discusses the theory and hypotheses to evaluate the PRR’s influence over aid. The third section provides an empirical evaluation of the hypotheses, discusses the results, and reports the results of sensitivity analyses. Finally, the concluding section presents implications of the findings.

The political economy of foreign aid

This section reviews three streams of research on the political economy of aid and draws implications from these studies to develop a theory and hypotheses. The first stream of studies is premised on the state-centric perspective that links aid and donor governments’ policy interests (Morgenthau, Reference Morgenthau1962). Recent research shows that while their specific objectives differ across time and space, donor governments use aid as leverage to achieve policy objectives in the recipient countries, including the maintenance of close diplomatic relations (Alesina and Dollar, Reference Alesina and Dollar2000), the promotion of democratic governance (Ziaja, Reference Ziaja2020), and the expansion of export markets (Barthel et al., Reference Barthel, Neumayer, Nunnenkamp and Selaya2014). These objectives yield the creation of political-economic environments in the recipient countries that are favorable to the donors’ interests, in turn establishing powerful aid-specific policy structures in the donor governments that obtain support from mainstream parties, irrespective of partisanship. Aid allocation based on such structures is resilient to diminution and will continue despite inadequate achievement of the stated goals of poverty reduction and economic development (Easterly, Reference Easterly2006). From this state-centric perspective, aid policy is exclusively determined by the establishment, including senior officials of mainstream parties, and appears to be free from populist politics.

The second research stream places domestic institutions and partisan ideologies in donor countries at the core of aid policymaking. This stream suggests that aid policy structures have sufficient political space within which partisan differences affect aid policy programs to certain degrees. For example, Lumsdaine (Reference Lumsdaine1993) views aid as a secondary activity of the welfare state institutions based on the social-democratic ideals of public-sector involvement in economic activity and income redistribution. Thérien and Noël (Reference Thérien and Noël2000) find that leftist mainstream parties with a history of augmenting welfare institutions have a limited immediate effect on aid but produce a cumulative long-term effect in expanding welfare institutions that, in turn, influences aid through social-democratic ideals.

Partially consistent with the institutional thesis above, the second research stream includes another perspective—that political parties have not only ideological convictions but also political goals to obtain government office and implement their preferred policies (Strøm, Reference Strøm1990). To achieve such goals and attract political support, they reflect their convictions and goals in party manifestos as policy pledges to voters (Budge et al., Reference Budge, Klingemann, Volkens, Bara and Tanenbaum2001). Parties seek to fulfill their pledges because a failure to do so will lead to the erosion of party credibility and political support (Bevan and Greene, Reference Bevan and Greene2017). Manifestos include not only domestic policy issues that directly determine voters’ well-being but also foreign policy issues that increasingly affect their well-being in an interconnected world (Greene and Licht, Reference Greene and Licht2018).

The above argument implies that partisan politics is deeply embedded in foreign policy instruments, including aid. Consistent with this idea, Tingley (Reference Tingley2010) finds a direct partisan ideological effect of the government on aid allocation. Greene and Licht (Reference Greene and Licht2018) explicitly measure government ideologies based on the right–left (RILE) orientations of governing parties as seen in their manifestos. This creates a unidimensional political space under which the left favors greater aid allocation than the right. Greene and Licht (Reference Greene and Licht2018) add another dimension of anti-internationalism to RILE, leading to a multidimensional space in which a combination of right and anti-international orientations is least favorable to aid allocation, but where a left–international orientation is most favorable. However, these studies do not consider coalition politics, which likely affect the partisan ideological effect. As elaborated in the next section, PRR parties use their electoral and political strength to engage in shrewd coalitional politics with mainstream parties to influence aid policy.

The third and emerging research stream focuses on the relationship between aid and immigration. The studies by Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015) demonstrate that donor countries utilize aid to moderate immigration through the reduction of poverty in the recipient countries, which is considered the root-cause of emigration, and increase aid to migrant-sending countries. However, this scenario has increasingly appeared overoptimistic, given the findings that aid money faces inefficient spending and even exploitation for personal enrichment by corrupt government officials and their clienteles, while motivating recipient governments to send migrant workers to the donor countries as lobbyists for more aid (Easterly, Reference Easterly2006; De Haas, Reference De Haas2007). Hence, aid’s moderating effect on immigration is called into question, likely inducing PRR parties’ condemnation and efforts to alter aid allocation.

More recently, researchers have begun to consider PRR influence more explicitly in conjunction with the aid–immigration nexus but have obtained mixed findings. Consistent with the finding by Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015), Hackenesch et al. (Reference Hackenesch, Högl, Öhler and Burni2022) show that PRR parties press for the expansion of aid budgets and the recalibration of aid programs. By contrast, Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Hackenesch and Stockemer2021) find that PRR votes and seats in parliaments are associated with the salience of the aid–immigration nexus in parliamentary debates. Heinrich et al. (Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Lawson2021) employ public opinion surveys in several developed countries and show that an increase in pro-PRR opinion defined as populism, anti-elitism, and nativism is correlated with aid reduction by donor governments. Hammerschmidt et al. (Reference Hammerschmidt, Meyer and Pintsch2022) find that PRR governments reduce aid spending because of their domestic politics concerns: the larger the share of PRR parties in the legislative and executive branches of government, the less aid is spent.

Overall, the studies in the three research streams provide an analytical scope to guide this study and illuminate lacunae to fill. Particularly, the studies in the first and second streams addressed the powerful aid-specific policy structures that ensure continuous aid allocation based on the establishment’s foreign policy considerations, mainstream parties’ ideological orientations, and aid’s immigration-controlling effect. Such structures deter outsiders from affecting policy and require modeling to decipher the PRR’s influence, if any. Equally important, the third stream of studies did not properly address the PRR’s impact on the aid–immigration nexus, particularly regarding some relevant theoretical and methodological issues.

First, no studies have modeled immigrant inflows as an intervening variable despite immigration heightening the PRR’s criticism over the efficacy of aid as an immigration control measure. Second, the existent studies did not use a bilateral framework that could assess properties in both donor and recipient countries that might affect the PRR’s strategies and aid allocation. In the absence of such a framework, they focused on total aid expenditures and thus were unable to ascertain changes in bilateral aid allocation. Specifically, donor governments under PRR pressure might allocate aid budgets to beef up patrol and border control in the countries en route from the immigrant-sending countries to the donor countries (Bergmann et al., Reference Bergmann, Hackenesch and Stockemer2021). In effect, total aid expenditures might have remained unchanged and even increased, while bilateral aid allocation to the specific immigrant-sending recipients might decline owing to the PRR’s punishment.

Thus, this study seeks to overcome the above issues and address the crucial research question: if aid policy fails to meet the establishment’s functional objective of stemming immigration, how do PRR parties handle the defunct aid policy? The following section presents a theory and hypotheses to address this question, whereas the empirical section presents a model for hypothesis testing.

Theory and hypothesis development

This study’s analysis hinges on the premise that PRR parties are qualitatively different from mainstream parties, including rightist ones, and may not act within the aid policy structures reviewed in the preceding section. Instead, PRR parties typically employ ideologies that diametrically oppose such structures. These ideologies differentiate PRR parties from mainstream right parties and motivate their political activities to exert unique policy influence unseen in mainstream politics. The proceeding text delineates the PRR’s ideologies of nativism and anti-establishment to predict the PRR effect on aid.

Nativism

Mudde (Reference Mudde2007, 19) defines nativism ‘as an ideology, which holds that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (‘the nation’) and that nonnative elements (persons and ideas) are fundamentally threatening to the homogenous nation-state.’ Betz (Reference Betz2019) distinguishes among a variety of nativist ideologies, including cultural, economic, and symbolic nativism and welfare chauvinism, and explains the interactions. In general, through nativist rhetoric, the PRR exploits the demarcation between nationals and foreigners from ethno-nationalistic perspectives, deepening horizontal differentiation (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Mudde, Reference Mudde2007). In particular, cultural nativism invites anti-immigration movements for national dominance, whereas economic nativism and welfare chauvinism lead to anti-aid movements for the well-being of the nationals. Aid policy may mollify anti-immigration movements if it reduces immigration. However, if it fails to do so, substitution between aid and immigration vanishes, motivating a welfare-chauvinistic PRR to advocate rechanneling taxpayers’ money from aid to domestic programs for the nationals who are strained and need government help, as articulated in the party manifestos quoted in the Introduction.

Anti-establishment

This is an ideology whereby PRR politicians identify themselves as being more ‘authentic representatives of the people’ than members of the establishment who hold ‘the political power to connect various social elites and debilitate political equality’ (Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019, 119). In stressing their anti-establishment identities, PRR politicians engage in exclusionary tactics to polarize domestic politics, by creating a division between the people and the establishment, deepening vertical differentiation and forging a mass movement that has profound influence on the political system (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017; Muller, Reference Muller2016). To boost popular support, they exploit the establishment’s policy failures in law and order by allowing immigration expansion and those in economic sovereignty by promoting integration (Albertazzi and Vampa, Reference Albertazzi and Vampa2021; Zaslove, Reference Zaslove2008). From this perspective, aid, along with immigration and integration, is viewed as deepening the division between the masses and the elites who appear to promote aid for these policies without popular consent. The anti-establishment narrative, combined with the nativism narrative, likely generates a strong impetus to alter the status-quo policies.

Politics of punishment

The above ideational profiles provide PRR parties with the behavioral patterns conducive to the politics of punishment. As articulated in the studies on criminology by Pratt (Reference Pratt2007) and Roberts et al. (Reference Roberts, Stalans, Hough and Indermaur2003), this populist policy-making style is susceptible to driving negative emotions such as ‘anger and resentment’ toward a sanction or a punitive approach to the sources of threat to ordinary citizens, such as crime and particular immigrant-sending countries (horizontal differentiation). Expressly, PRR parties appeal to those who see themselves as disenfranchised by the establishment, by engaging in the politics of punishment, rather than the existent preventive policy espoused by the establishment that has failed to stem immigration (vertical differentiation). In this sense, the defunct aid policy acts as the pivotal issue that unites the people who feel victimized by the establishment, by allowing the people abroad to prosper. The politics of punishment in aid is, therefore, an intersection of vertical and horizontal differentiations by the PRR.

Although the punitive approach may be ineffective in stemming immigration, it connotes the cynical exploitation of aid policy for political purposes. It stimulates ‘hostile solidarity’ between PRR politicians and the people via an us-against-them mentality (Carvalho and Chamberlen, Reference Carvalho and Chamberlen2018). This is further reflected in the definition of ‘anti-reason populism’ by Pratt and Miao (Reference Pratt and Miao2017); they argue that populists allow the electoral advantage of a policy to take precedence over its effectiveness. The reduction of aid upon the establishment’s failure regarding immigration control is politically rational for the PRR. It becomes possible to use the saved aid money to augment border control or other domestic welfare programs for the people who need government protection (Krause and Giebler, Reference Krause and Giebler2020).

Influence pathways

The previous discussion provides the ideational sources of the PRR-led politics of punishment without defining an avenue for policy influence. The literature suggests two pathways for policy influence. The direct pathway is derived from the coalitional capacity to take part in government with mainstream parties (de Lange, Reference De Lange2012; Lutz, Reference Lutz2019). If the PRR poses an electoral threat, the most threatened mainstream right parties have an incentive to adopt a coalitional strategy to diffuse the threat by inviting the PRR into a government coalition (Meguid, Reference Meguid2008; Twist, Reference Twist2019).Footnote 2 When an issue (e.g., immigration) is salient, ideological proximity matters in the formation of a coalition between the mainstream right and the PRR (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). Through this coalition strategy, mainstream parties can boost their policy credibility for tighter immigration control by internalizing the PRR’s electoral strength (Akkerman and Rooduijn, Reference Akkerman and Rooduijn2015; van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2011). Whereas mainstream parties benefit from PRR electoral success that provides a strategic asset to consolidate a government office and expand their support base, PRR parties obtain direct access to policymaking capabilities that they vitally lack (Lutz, Reference Lutz2019; Twist, Reference Twist2019). Thus, such a partnership is mutually beneficial for PRR and mainstream right parties and can overcome the ideational differences between them. This pragmatic behavior is summarized by Akkerman (Reference Akkerman2015), who argues that PRR parties break from unilateral opposition and increasingly cooperate with other parties without moderating their anti-establishment ideology.

By contrast, an indirect pathway relies on the PRR’s electoral capacity to influence interparty competition toward its preferred direction by stressing a salient political issue and mobilizing popular sentiment (Bale et al., Reference Bale, Green-Pedersen, Krouwel, Luther and Sitter2010; Schain, Reference Schain2006). This is because, in general, voters take account of whether a party is the most credible proponent of a particular issue when casting their ballots. Owing to such voter calculus, parties are expected to perform well electorally when they are viewed as owning the issues they promote and when these issues are salient (Budge and Farlie, Reference Budge and Farlie1983; Petrocik, Reference Petrocik1996). When an immigration issue becomes salient in elections, it boosts political support for PRR parties that have ownership over the issue by advocating tighter immigration control to protect domestic workers and social order (e.g., Barone et al. [Reference Barone, D’Ignazio, de Blasio and Naticchioni2016] on Italy; Brunner and Kuhn [Reference Brunner and Kuhn2018] on Switzerland; Halla et al. [Reference Halla, Wagner and Zweimüller2017] on Austria). They typically have associative ownership over the issue by addressing it in a manner sympathetic to the ordinary citizens (Lachat, Reference Lachat2014).Footnote 3

The PRR’s electoral success based on associative ownership alters the policy space and turns existent government policy into an electoral liability, hence discouraging mainstream parties from maintaining it. To avoid losing votes to the PRR challenger in future elections, mainstream parties accommodate the PRR’s policy advocacy. The indirect pathway assumes that mainstream parties establish government coalitions on their own without PRR participation or support. Yet, it prompts mainstream parties to amend the existing policy course by adopting the policy advocated by the PRR to maintain popular support for their coalition governments (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017).

Taken together, the two pathways provide the PRR with opportunities to engage in the politics of punishment. In aid policy, such politics takes the form of punitive aid reduction to the recipient countries that send numerous immigrants into the donor countries. It is a juncture of horizontal and vertical differentiations through which the PRR seeks to punish the immigrant-sending countries for degrading the well-being of the ordinary citizens and condemn the establishment for failing to control immigration. The horizontal and vertical differentiation strategies are consistent with and derived from the PRR ideational profiles of nativism and anti-establishment, respectively. This argument leads to a falsifiable hypothesis:

H1: The amount of bilateral aid allocation by a donor country to recipient countries is negatively correlated with the PRR coalitional or electoral capacity in the donor country, conditioned upon immigrant inflows therefrom.

The PRR’s policy influence on aid is substitutive to immigrant inflows and takes advantage of the direct or indirect pathways. The relative weights of the two pathways are indeterminate at the theoretical level and will be ascertained in the proceeding section. The remainder of this section hypothesizes that PRR policy influence accrues from the ability to exploit the horizontal and vertical differentiation strategies in conjunction with recipient countries’ heterogeneous sociocultural characteristics and donor countries’ weak pluralistic political systems.

First, the PRR construes the people as a culturally or ethnically bounded collectivity and sees that collectivity as threatened by outside groups (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017). In general, when outside groups have sociocultural characteristics distinct from the homogenous collectivity, such distinction intensifies horizontal differentiation and aggravates voters’ negative emotions toward them. The studies by Brunner and Kuhn (Reference Brunner and Kuhn2018) and Davis and Deole (Reference Davis and Deole2015) show that immigrants’ sociocultural characteristics affect voters’ emotions and their support for the PRR parties exploiting such characteristics. It can be inferred from the studies that punitive aid-reducing pressure toward recipient countries will be more intense if they send substantial numbers of immigrants to the donor countries and have sociocultural characteristics different from the donor countries’ ordinary citizens. This argument can be hypothesized as follows:

H2: The extent of aid-reducing pressure derived from PRR coalitional and/or electoral capacity is positively correlated with the degree of sociocultural difference between the donor and the recipient countries sending numerous immigrants to the donor country.

Populism reacts against a tension within liberal democracy between the ideal of popular representation and the pluralistic institutions which constrain the power of popular sovereignty (Lacey, Reference Lacey2019; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2019). This is because PRR leaders believe that elites have established a pluralistic system to constrain the will of the people they represent. They stand for populist democracy, unafraid of sidestepping the constitutional procedures (negative integration) to infuse their will directly into government policy through a plebiscitary approach.Footnote 4

In principle, a pluralistic system of checks and balances subdues emotions for reasoned or rational policymaking via rule-based procedures (Dahl, Reference Dahl1956). Institutionalized pluralism diversifies sources of political power and ameliorates vertical differentiation between the masses and the elites (Brubaker, Reference Brubaker2017). On the contrary, a weak pluralistic system, or ‘populistic democracy,’ relaxes the institutional constraints and is susceptible to the rhetorical practice of negative integration, thus being conducive to the exploitation of vertical differentiation by the PRR. Accordingly, considering other things as equal, PRR punitive aid-reducing pressure will be intense if a donor country has a weak pluralistic system. This argument can be written as:

H3: The extent of aid-reducing pressure derived from PRR coalitional and/or electoral capacity is positively correlated with the weakness of the pluralistic institutional arrangements in the donor country.

Empirical model

This empirical section evaluates the three hypotheses through a panel design against the aid policy experiences of Western European democracies. To conduct such analysis, a linear two-way fixed effects (FE) model is constructed and is expressed by,

The dependent variable,

![]() $A_{ijt}^{}$

, on the left-hand side of equation (1), is measured as the logarithm of the ratio of bilateral aid to gross domestic product (GDP) committed by donor country

$A_{ijt}^{}$

, on the left-hand side of equation (1), is measured as the logarithm of the ratio of bilateral aid to gross domestic product (GDP) committed by donor country

![]() $i$

to recipient country

$i$

to recipient country

![]() $j$

in year

$j$

in year

![]() $t$

(constant USD). The aid variable includes all aid categories which, from the perspective of strategic migration, can motivate emigration to donor countries and thus are susceptible to curtailment. The data on bilateral aid were drawn from the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) (OECD, 2021).

$t$

(constant USD). The aid variable includes all aid categories which, from the perspective of strategic migration, can motivate emigration to donor countries and thus are susceptible to curtailment. The data on bilateral aid were drawn from the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) (OECD, 2021).

The equation presented has a potential technical problem related to the censored (non-negative) and volatile characteristics of bilateral aid allocation as the dependent variable. Estimating such an equation with all observations would result in a large bias. Empirical studies on aid allocation treat this problem by estimating equations on samples restricted to strictly positive variables (Alesina and Dollar, Reference Alesina and Dollar2000; Greene and Licht, Reference Greene and Licht2018; Tingley, Reference Tingley2010). They transform aid allocation in logarithmic form, which facilitates interpretation of regression coefficients as elasticities. However, this method may create a second bias, known as selection bias, which is derived from the fact that the selection of a country as a recipient of aid may depend on variables that also influence the amount of aid. It is difficult to resolve selection bias, without credible instruments that could account for the selection of a recipient country, but not the amount of aid that it receives. As a second-best measure, this study ascertains the severity of selection bias via a simple reverse causality test to check feedback effects later in the empirical analysis.

The equation has two variables on the right-hand side that represent the two pathways for PRR policy influence. One is

![]() $C_{it - 1}^{}$

, for the PRR’s coalitional capacity measured by the share of seats controlled by the PRR parties that participate in or provide external support for government coalitions in year

$C_{it - 1}^{}$

, for the PRR’s coalitional capacity measured by the share of seats controlled by the PRR parties that participate in or provide external support for government coalitions in year

![]() $t - 1$

in donor country

$t - 1$

in donor country

![]() $i$

. Another variable is

$i$

. Another variable is

![]() $E_{it - 1}^{}$

, for electoral capacity measured as the share of parliamentary seats controlled by all PRR parties in year

$E_{it - 1}^{}$

, for electoral capacity measured as the share of parliamentary seats controlled by all PRR parties in year

![]() $t - 1$

in donor country

$t - 1$

in donor country

![]() $i$

(data on parliamentary seats and votes are from Döring and Manow [Reference Döring and Manow2020]). This model follows Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, de Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) in identifying ‘far right populist’ as PRR parties in parliaments and Mudde (Reference Mudde and Mudde2016) in identifying PRR parties in government coalitions (See the online supplementary material for the list).

$i$

(data on parliamentary seats and votes are from Döring and Manow [Reference Döring and Manow2020]). This model follows Rooduijn et al. (Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, de Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019) in identifying ‘far right populist’ as PRR parties in parliaments and Mudde (Reference Mudde and Mudde2016) in identifying PRR parties in government coalitions (See the online supplementary material for the list).

In the aforementioned theory, PRR parties influence aid allocation through coalitional capacity conditioned by immigrant inflows. To evaluate the hypothesis, the model includes the variable,

![]() ${M_{ijt - 1}}$

, which measures the net immigrant inflow to donor country

${M_{ijt - 1}}$

, which measures the net immigrant inflow to donor country

![]() $i$

(the number of immigrants in ten thousand) from recipient country

$i$

(the number of immigrants in ten thousand) from recipient country

![]() $j$

in year

$j$

in year

![]() $t - 1$

(data on immigration are from the International Migration Database by the OECD [2022]). Following the recommendation by Lanati and Thiele (Reference Lanati and Thiele2018), this study uses immigrant flows rather than stocks to assess the aid-migration nexus. Using stocks may be misleading as aid cannot directly affect stocks or the number of immigrants who were born in their country of origin and have resided in donor countries for a long period of time.

$t - 1$

(data on immigration are from the International Migration Database by the OECD [2022]). Following the recommendation by Lanati and Thiele (Reference Lanati and Thiele2018), this study uses immigrant flows rather than stocks to assess the aid-migration nexus. Using stocks may be misleading as aid cannot directly affect stocks or the number of immigrants who were born in their country of origin and have resided in donor countries for a long period of time.

The immigrant inflow variable interacts with coalitional capacity,

![]() ${C_{it - 1}}$

, and electoral capacity,

${C_{it - 1}}$

, and electoral capacity,

![]() ${E_{it - 1}}$

, to assess the PRR effects on bilateral aid allocation conditioned by immigrant inflows. The hypothesis predicts that the coefficients on the interaction terms

${E_{it - 1}}$

, to assess the PRR effects on bilateral aid allocation conditioned by immigrant inflows. The hypothesis predicts that the coefficients on the interaction terms

![]() $M_{ijt - 1}^{}C_{it - 1}^{}$

and

$M_{ijt - 1}^{}C_{it - 1}^{}$

and

![]() $M_{ijt - 1}^{}E_{it - 1}^{}$

will be negative and significant. The use of these interaction terms differentiates this study from existing studies on PRR effects by Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Hackenesch and Stockemer2021), Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015), Hackenesch et al. (Reference Hackenesch, Högl, Öhler and Burni2022), Hammerschmidt et al. (Reference Hammerschmidt, Meyer and Pintsch2022), and Heinrich et al. (Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Lawson2021).

$M_{ijt - 1}^{}E_{it - 1}^{}$

will be negative and significant. The use of these interaction terms differentiates this study from existing studies on PRR effects by Bergmann et al. (Reference Bergmann, Hackenesch and Stockemer2021), Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015), Hackenesch et al. (Reference Hackenesch, Högl, Öhler and Burni2022), Hammerschmidt et al. (Reference Hammerschmidt, Meyer and Pintsch2022), and Heinrich et al. (Reference Heinrich, Kobayashi and Lawson2021).

Control variables

The equation contains a vector of covariates,

![]() ${X_{t - 1}}$

, defined as follows. Consistent with the studies on aid reviewed earlier, the covariates model the aid policy structures based on the ideological, foreign policy, and commercial determinants.

${X_{t - 1}}$

, defined as follows. Consistent with the studies on aid reviewed earlier, the covariates model the aid policy structures based on the ideological, foreign policy, and commercial determinants.

First, to measure the ideological orientations of parties in government, this study followed Greene and Licht (Reference Greene and Licht2018) in using the logged-scale of RILE ideology. RILE is computed from the manifestos of the governing parties, weighted by the shares of their votes in parliamentary elections,Footnote 5 using Lowe et al.’s (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) logged scale of parties’ RILE placement to operationalize governments’ broad policy goals in the right–left continuum. Left-leaning positions focus on the role of governments in decreasing economic inequality; more rightist positions tolerate inequality in the name of economic development and market liberalization (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Jolly and Polk2012). Thus, logged scale RILE captures responses to social, economic, and political inequality by all governing parties, including PRR parties, but does not address the PRR’s ideational profiles discussed earlier. Thus, by controlling for logged scale RILE, equation (1) can capture effects on aid allocation of the PRR’s coalitional and electoral capacities that derive uniquely from the ideational profiles of nativism and anti-establishment. The variable on anti-internationalism by Greene and Licht (Reference Greene and Licht2018) is not employed because RILE fulfills the study’s theoretical objective of capturing ideological orientations in government and because anti-internationalism overlaps the PRR’s nativist rhetoric.

Other determinants of the aid policy structures discussed earlier, comprise (1) the degree of electoral democracy in the recipient country

![]() $i$

(data on the electoral democracy index are from the V-DEM Institute 2022); (2) foreign policy disagreement, measured as the distance between ideal points of

$i$

(data on the electoral democracy index are from the V-DEM Institute 2022); (2) foreign policy disagreement, measured as the distance between ideal points of

![]() $i$

and

$i$

and

![]() $j$

estimated based on their rollcall votes in the United Nations General Assembly (data on agreement are from Voeten et al. [Reference Voeten, Anton Strezhnev and Bailey2009]); (3) the logarithm of the share of exports by donor country

$j$

estimated based on their rollcall votes in the United Nations General Assembly (data on agreement are from Voeten et al. [Reference Voeten, Anton Strezhnev and Bailey2009]); (3) the logarithm of the share of exports by donor country

![]() $i$

to recipient country

$i$

to recipient country

![]() $j$

in the GDP (data on exports and GDP are from the Comparative Welfare States (CWS) Dataset by Brady et al. [Reference Brady, Hubber and Stephens2020]); and (4) the cumulative share of seats in parliament held by leftist parties controlling cabinet from 1946 to the year of the observation (Thérien and Noël, Reference Thérien and Noël2000) (data are from the CWS Dataset by Brady et al. [Reference Brady, Hubber and Stephens2020]). Two additional economic covariates are incorporated into the equation. First, the international objective of aid outlined by the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD dictates donor countries to allocate aid to low-income recipients, measured as GDP per capita (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Dreher and Nunnenkamp2014). Second, aid donors face domestic economic constraints, which are modeled as the logarithm of the real GDP per capita in donor country

$j$

in the GDP (data on exports and GDP are from the Comparative Welfare States (CWS) Dataset by Brady et al. [Reference Brady, Hubber and Stephens2020]); and (4) the cumulative share of seats in parliament held by leftist parties controlling cabinet from 1946 to the year of the observation (Thérien and Noël, Reference Thérien and Noël2000) (data are from the CWS Dataset by Brady et al. [Reference Brady, Hubber and Stephens2020]). Two additional economic covariates are incorporated into the equation. First, the international objective of aid outlined by the Development Assistance Committee of the OECD dictates donor countries to allocate aid to low-income recipients, measured as GDP per capita (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Dreher and Nunnenkamp2014). Second, aid donors face domestic economic constraints, which are modeled as the logarithm of the real GDP per capita in donor country

![]() $i$

in year

$i$

in year

![]() $t - 1$

(data on GDP per capita are from the World Development Indicators by the World Bank [2021]). Third, conflicts in recipient countries may be a confounder for equation (1) that affects both immigrant flows and aid allocation (data on conflicts were from Pettersson [Reference Pettersson2021]).

$t - 1$

(data on GDP per capita are from the World Development Indicators by the World Bank [2021]). Third, conflicts in recipient countries may be a confounder for equation (1) that affects both immigrant flows and aid allocation (data on conflicts were from Pettersson [Reference Pettersson2021]).

Estimation

To capture idiosyncratic effects in panel data, equation (1) includes two-way FEs for donor–recipient pairs, denoted by

![]() ${u_{ij}}$

, and for time, denoted by

${u_{ij}}$

, and for time, denoted by

![]() ${v_t}$

. An error term is

${v_t}$

. An error term is

![]() ${\varepsilon _{it}}$

. Linear two-way FE models are widely used in social science studies to estimate causal effects of explanatory variables in panel data by removing the effects of unobserved time-invariant cofounders (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). The equation was estimated with two-way FEs via ordinary least squares (OLS) based on the annual data covering 17 donor countries and 112 recipient countries between 1995 and 2018.Footnote

6

The statistical analysis begins in 1995, when PRR parties gained political strength, and extends until the most recent available data at the time of writing. The time frame includes the early and mid-2010s when massive immigrant inflows from the Middle East and Africa occurred in Western European countries owing to the Arab Spring and the wars in Syria and Sudan. The descriptive statistics of all data used in this study are shown in the supplementary material.

${\varepsilon _{it}}$

. Linear two-way FE models are widely used in social science studies to estimate causal effects of explanatory variables in panel data by removing the effects of unobserved time-invariant cofounders (Angrist and Pischke, Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). The equation was estimated with two-way FEs via ordinary least squares (OLS) based on the annual data covering 17 donor countries and 112 recipient countries between 1995 and 2018.Footnote

6

The statistical analysis begins in 1995, when PRR parties gained political strength, and extends until the most recent available data at the time of writing. The time frame includes the early and mid-2010s when massive immigrant inflows from the Middle East and Africa occurred in Western European countries owing to the Arab Spring and the wars in Syria and Sudan. The descriptive statistics of all data used in this study are shown in the supplementary material.

Empirical results

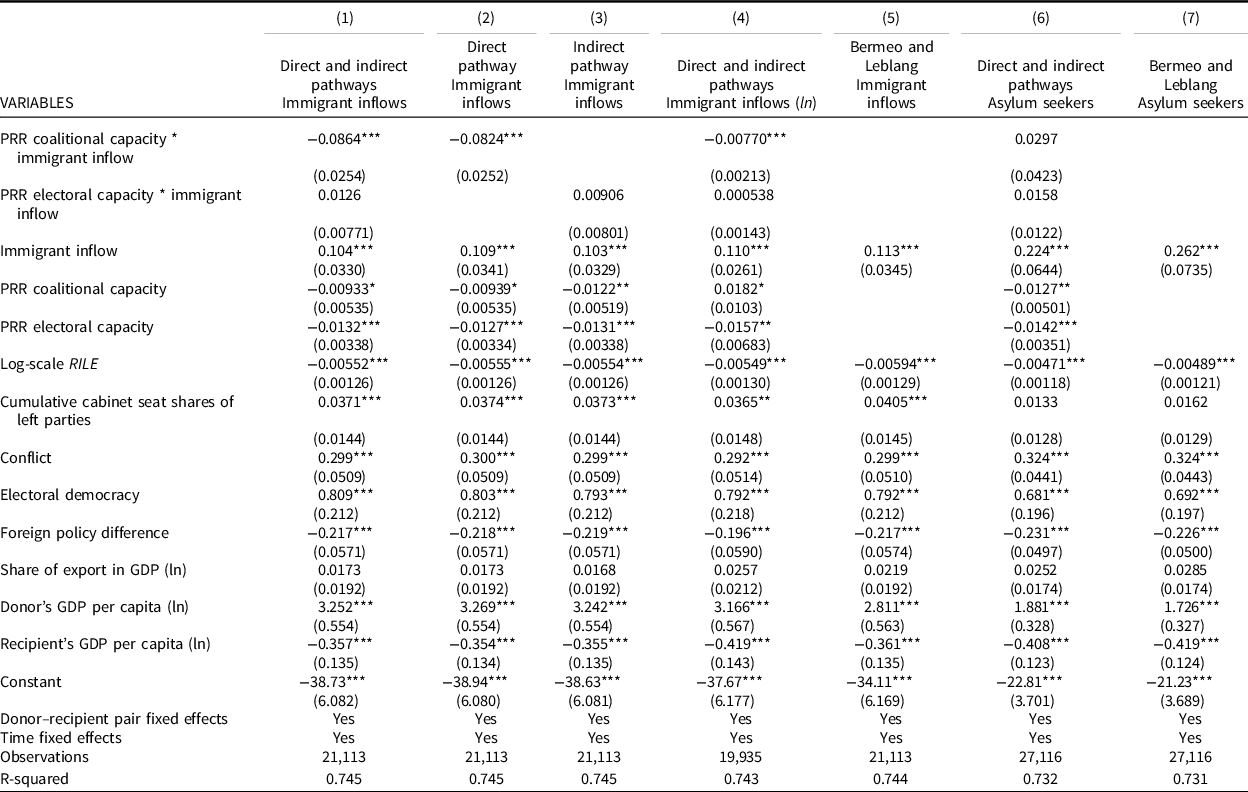

The OLS coefficient estimates of equation (1) are reported in Table 1. Expressly, the estimates render empirical support for H1 by showing that donor coalition governments with PRR participation or external support reduce bilateral aid allocation to the recipient countries that send substantial numbers of immigrants to their countries.

Table 1. Populist radical right’s impacts on bilateral aid conditioned by immigrant inflows

Notes: Estimation was made using ordinary least squares with all variables on the right-hand side of equation (1) being lagged by one year. Robust standard errors clustered in panel pairs are in parentheses. *** indicates P < 0.01; **, P < 0.05; and *, P < 0.1.

The estimates in columns (1) and (2) show that the key interaction term between PRR coalitional capacity and immigrant inflow is negatively and significantly correlated with bilateral aid to the recipient countries at the 95% confidence level. The coefficient is estimated as −0.0864, which suggests that a one-unit increase in the share of parliamentary seats held by PRR parties in government, or immigration flow (in ten thousand), is associated with approximately 8% decline in bilateral aid (.28).

By contrast, the other interaction term between PRR electoral capacity and immigrant inflows is insignificant. Columns (3) and (4) use the logarithm of immigrant inflows because of the volatile characteristics (no immigrants from many recipient countries) and show the estimates similar to those in (1) and (2). These results suggest that PRR parties can influence aid only through the direct pathway to policymaking capability.

In Table 1, column (5) shows the estimates of the model by Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015) and suggests that immigrant flows have a positive effect on bilateral aid in the absence of PRR effects. This result is consistent with their complementarity thesis that a large immigrant inflow increases aid to the recipient countries to reinforce anti-poverty efforts and prevent further emigration. However, the results discussed, already indicate that PRR coalitional capacity, if properly modeled, has a reducing effect on aid.

Columns (6) and (7) show the estimates of equation (1) and the model by Bermeo and Leblang (Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015) that replace immigrant inflows with the inflows of asylum seekers, respectively. In (6), both the interaction terms for the direct and indirect pathways are insignificant, whereas, in (7), the number of asylum seekers is positively correlated with aid. The results suggest that donor governments with and without PRR influence have humanitarian concerns for asylum seekers, differentiating them from immigrants with potential economic motives.

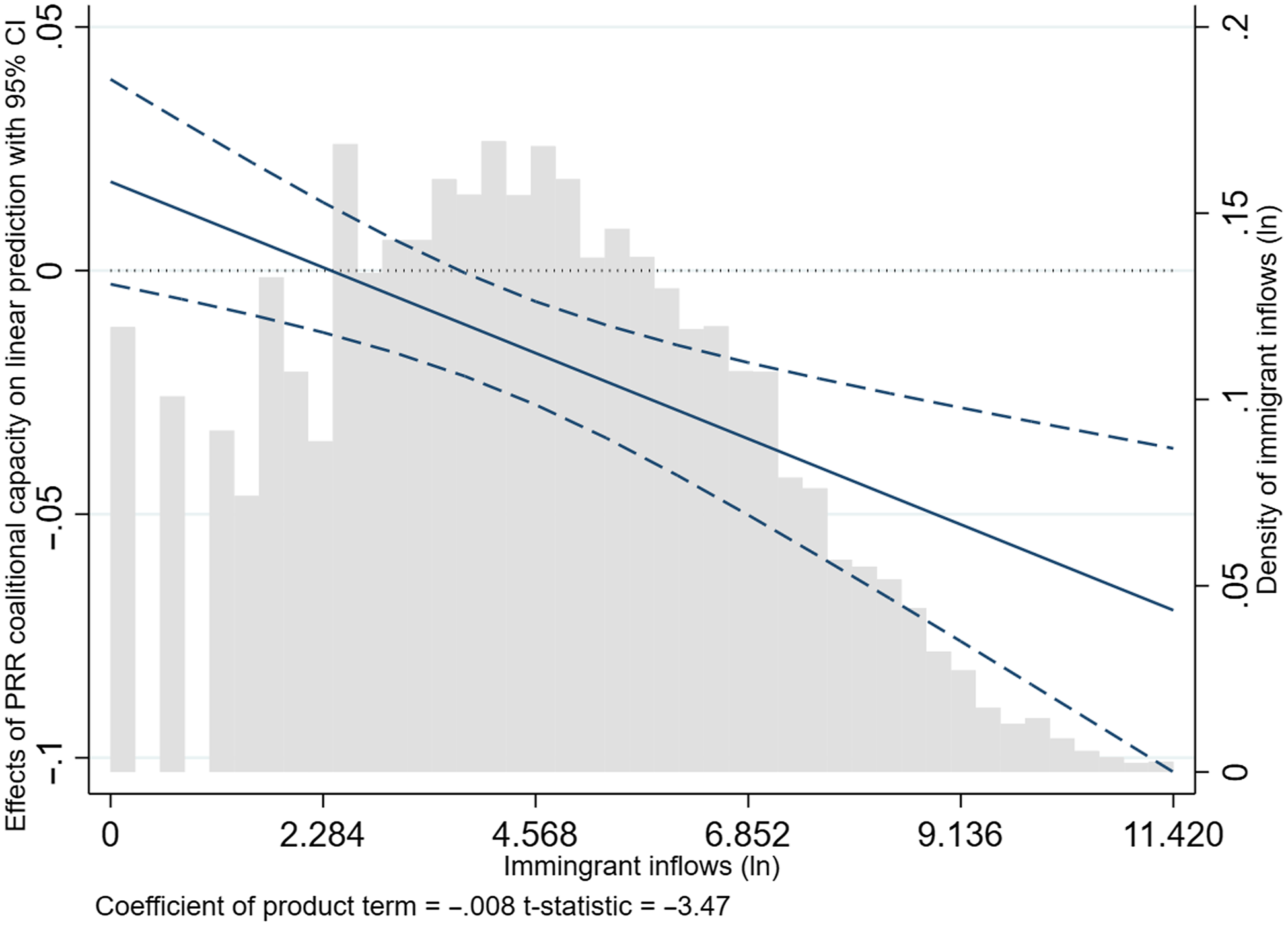

The findings thus far uncover a significant decrease in the volume of bilateral aid allocation specifically to the recipient countries in conjunction with immigrant flows into the donor countries. To show that the PRR’s aid-reducing effects are not due to a particular level of immigrant inflow, Figure 1 plots the average marginal effects with the histogram of the logged immigrant inflows, using the estimates in column (3) of Table 1. In the figure, the negatively sloped solid curve indicates increases in immigrant inflows leading to the deepening of the PRR’s aid-reducing effects via the direct pathway. The two dotted lines for the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals are proximate to the solid line, meaning that immigrant inflows have a symmetric conditioning impact across the marginal effects. This is buttressed by the histogram showing that the vertical bars representing logged immigrant inflows are widely dispersed across the horizontal axis.

Figure 1. Marginal Effects of Radical Populist Coalitional Effect on Bilateral Aid Allocation Conditioned by Immigrant Inflows.

Notes: The figure was constructed from the estimates of column (3) in Table 1. The solid line represents the marginal effects of populist radical right coalitional capacity on bilateral aid conditioned by logged immigrant inflows. The dotted lines indicate the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The vertical bars indicate the density of logged immigrant inflows.

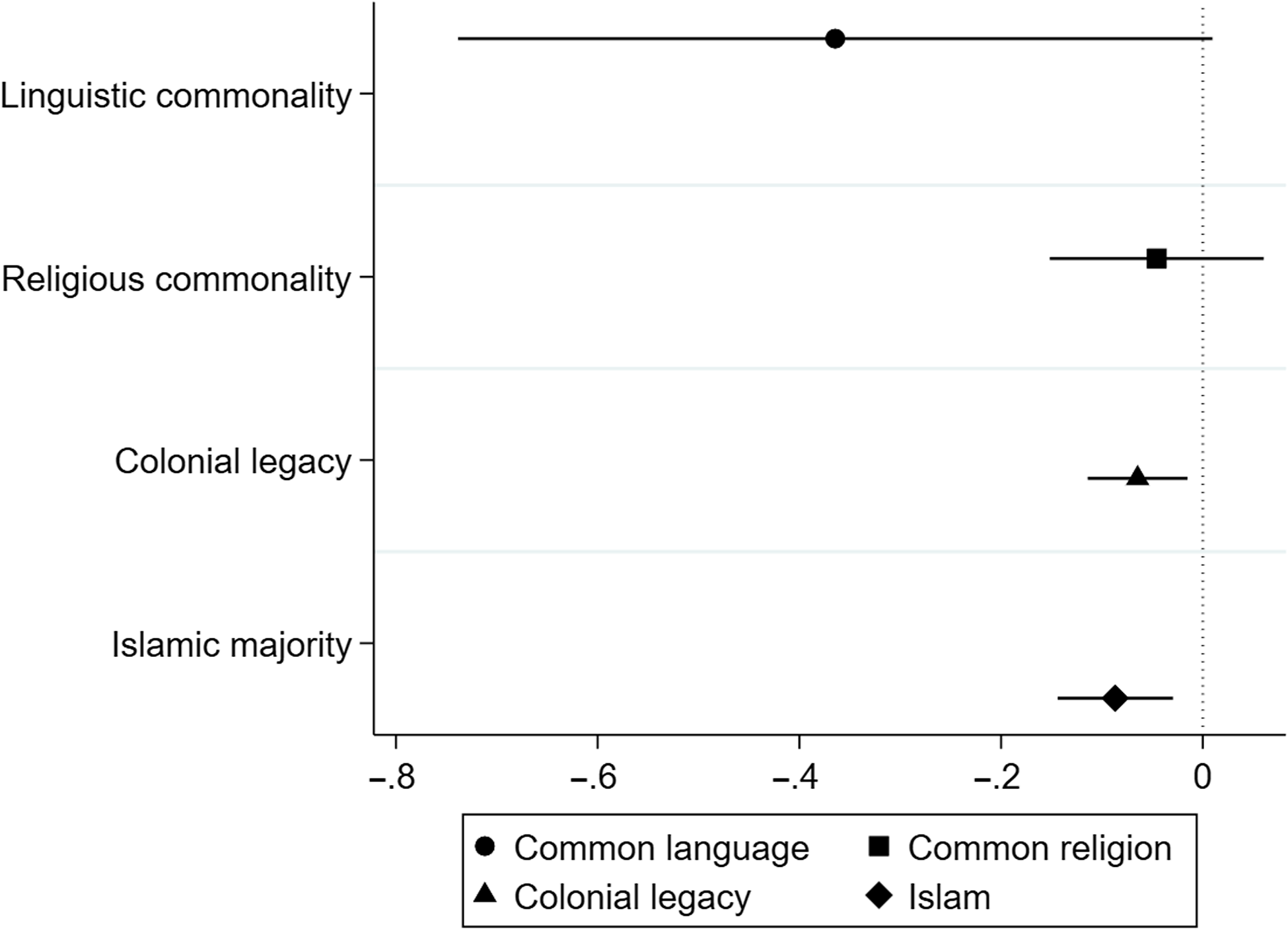

The second hypothesis predicts that immigrants’ particular sociocultural characteristics amplify the PRR’s punitive aid-reducing pressure by allowing them to exploit horizontal differentiation. Drawing on the findings by Brunner and Kuhn (Reference Brunner and Kuhn2018) and Davis and Deole (Reference Davis and Deole2015), the analysis here focuses on (1) linguistic commonality, (2) religious commonality, (3) colonial legacy between immigrants’ home countries and the arriving donor countries, and (4) the share of Islamic population in the immigrants’ home countries.Footnote 7 In equation (1), these sociocultural variables are interacted with PRR coalitional capacity and immigrant inflows. To test H2, the augmented equation was estimated via OLS.

Figure 2 plots the coefficient estimates of the key interaction term and shows that, among the four variables above, only religious commonality is absolutely insignificant (linguistic commonality is almost significant with a large coefficient magnitude), meaning that it has a significant moderating impact on the PRR aid-reducing effect. Religious commonality weakens the punishment perhaps because it eases voter negative emotion by facilitating mutual understanding between immigrants and residents in donor countries, thus lessening the PRR’s horizontal differentiation, even if recipient countries send many immigrants to the donor countries.

Figure 2. Immigrants’ Sociocultural Characteristics and the Populist Radical Right’s Policy Influence.

Notes: The four variables were interacted with immigrant inflows and the share of parliamentary seats held by populist radical right parties that participated in or provided external support for government coalitions in equation (1). Estimation was made by ordinary least squares. The symbols represent point coefficient estimates of the interaction term. The bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The next analysis evaluates H3 which posits that weak pluralistic institutions in donor countries intensify the PRR’s aid-reducing pressure by relaxing constraints on the exploitation of vertical differentiation. Since most countries studied here adopt parliamentary systems with proportional representation, it is impossible to ascertain the effects of parliamentary–presidential and single-member district–proportional representation dichotomies on PRR policy influence. Thus, the analysis here focuses on the constraining effects of other institutional arrangements, including strong bicameralism, federalism, non-plebiscite, and judicial review, which are shown to be resistant to the PRR’s policy (See Arzheimer and Carter [Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006]; See also Golder [Reference Golder2016] and Muis and Immerzeel [Reference Muis and Immerzeel2017] for summaries of findings).

To assess H3, equation (1) was estimated separately for donor countries with strong bicameralism (two chambers with relatively equal power) and those with weak bicameralism (two chambers, one substantially stronger than the other) or unicameralism. Additionally, the equation was estimated for plebiscitary and non-plebiscitary democracies, federal and non-federal government structures, and the presence and absence of judicial review in the political system (data on these variables are from the CWS Dataset by Brady et al. [Reference Brady, Hubber and Stephens2020]).

The results are shown in Figure 3. As predicted, rows (2), (4), and (6) show that the estimated coefficient remains significantly negative for weak bicameralism or unicameralism, plebiscitarism, and no or weak federalism, while rows (1), (3), and (5) show that it is insignificant for the opposite arrangements. By contrast, row (7) on the presence of judicial review shows that the coefficient remains negative and significant, while row (8) on the absence shows that the coefficient is almost significant, suggesting that PRR policy influence occurs even under judicial review. Altogether, the results support H3, by showing that the weak pluralistic institutions, characterized as weak bicameralism or unicameralism, plebiscitarism, and non-federalism, enhance PRR parties’ policy influence through the direct pathway by motivating them to exploit vertical differentiation.

Figure 3. Institutional Arrangements and the Populist Radical Right’s Policy Influence.

Notes: Estimation of equation (1) was made via ordinary least squares for donor countries with the specified institutional arrangements. The symbols represent the point coefficient estimates of the interaction term between immigrant inflow and the share of seats held by populist radical right parties that participated in or provided external support for government coalitions. The bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Sensitivity tests

Three sensitivity tests were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the main finding for H1. The test results are reported as follows.

-

(1) Feedback effects. A common criticism of linear FE models and the log transformation of the dependent variable used in this study is that the main interaction term may respond to preceding declines in aid allocation due to the selection biases discussed earlier. Following the recommendation by Angrist and Pischke (Reference Angrist and Pischke2008), the first test investigated changes in aid allocation before and after PRR government involvement. To do so, the original equation was estimated with leads of the key interaction term and associated variables for each of the three years prior to PRR government involvement and for each of the four years including and following PRR government involvement. As before, the two-way FEs and the control variables were maintained. In this case, insignificant coefficients on the leads of the key interaction term are taken as evidence that, conditional on covariates, PRR involvement and non-involvement cases were similar before PRR coalitional capacity was assigned, which suggests that selection bias does not account for the apparent effect of PRR punishment.

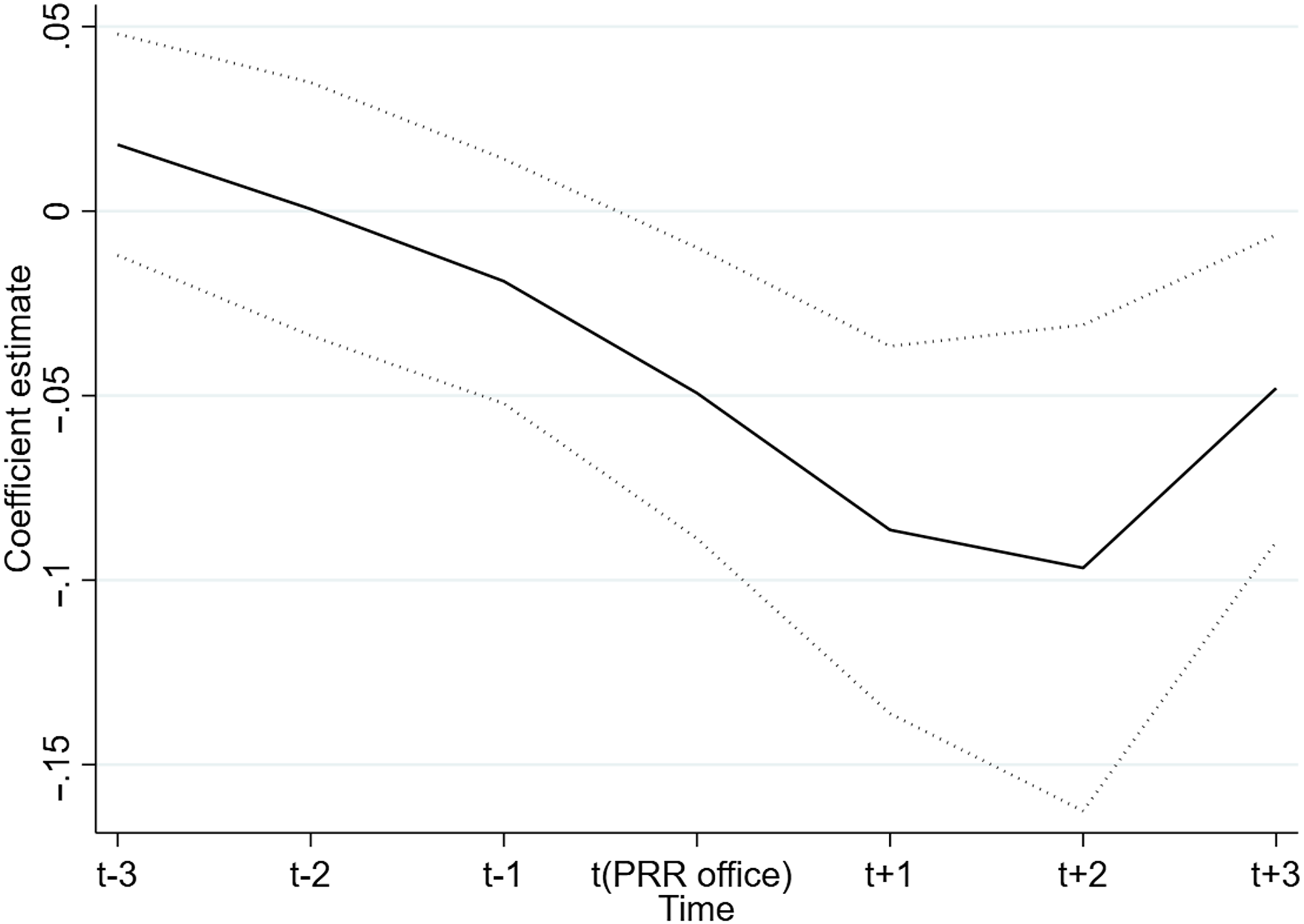

Figure 4 shows that the coefficient estimates for the pre-PRR government involvement interaction term are insignificant in the four years in advance (t − 3, t − 2, t − 1, and t). This test provides evidence that the result is not driven by pre-PRR government involvement trends in aid allocation. Instead, aid allocation started to fall precisely one year after PRR government involvement, with the aid-reducing effects emerging over a period of two years (t + 1, t + 2, and t + 3). The key interaction term remains significantly negative, providing additional support for the robustness of the PRR aid-reducing effect to feedback effects. However, a usual caveat is in order. The linear FE model hinges on the assumption of the PRR’s homogeneous effect across donor–recipient pairs and time. It is implausible that the effects are constant. Relatedly, the analysis controlled for observed covariates and time-invariant cofounders but overlooked unmeasured time-varying cofounders that might influence the estimates.

-

(2) Alternative coding. The second test confirms that the result is not derived from the choice of the particular coding scheme for PRR government involvement. The coefficient estimates from the alternative schemes by Akkerman et al. (Reference Akkerman, de Lange and Rooduijn2016) and Lutz (Reference Lutz2019) are very similar to those from the original Mudde scheme in Table 1, suggesting that the result is robust to the alternative coding schemes (the results are in the supplementary material to conserve space).

-

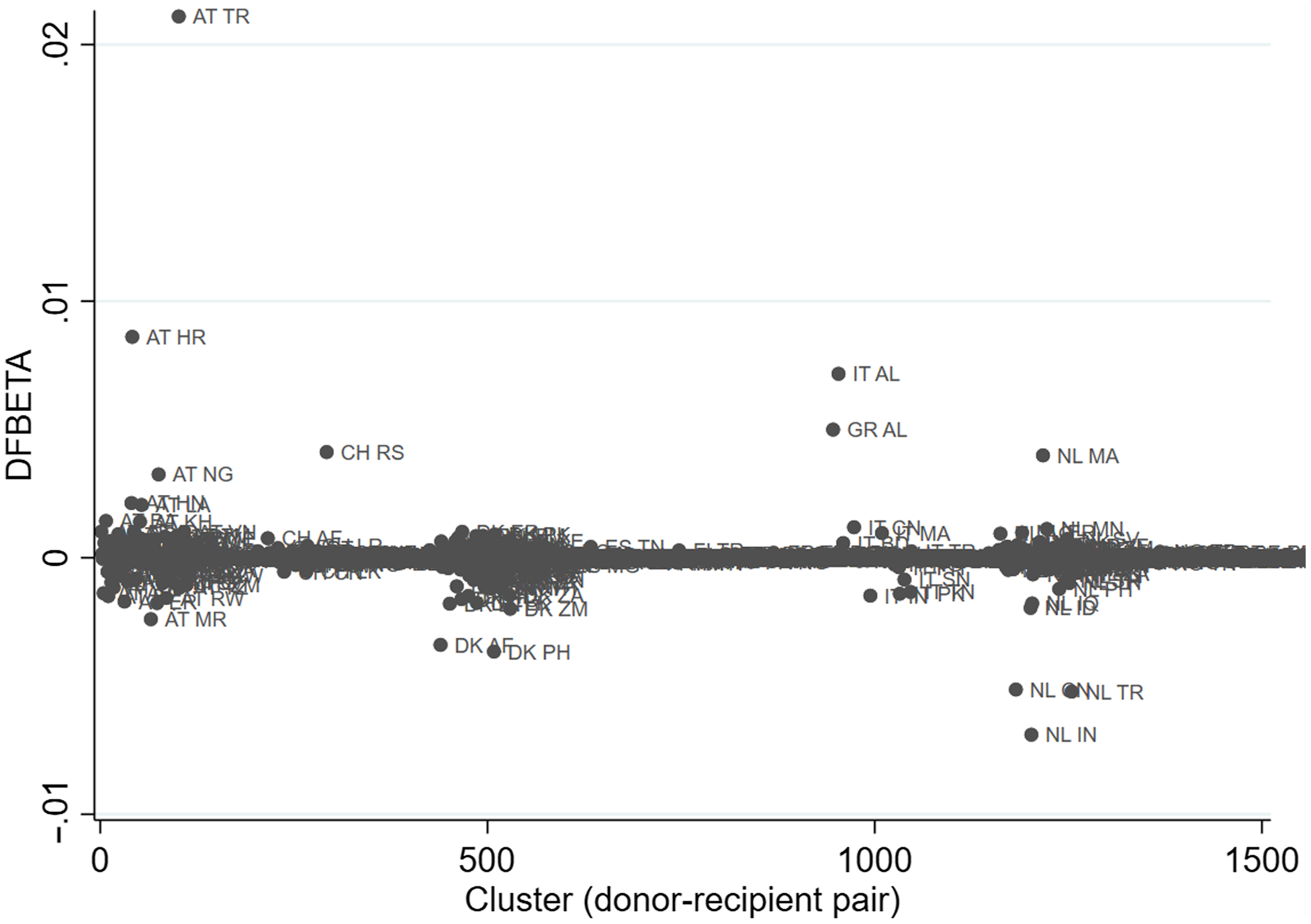

(3) Influential clusters. The third test used Jackknife resampling to confirm that the result is not driven by ‘influential’ observations, or clusters of donor–recipient pairs.Footnote 8 Figure 5 plots the values of DFBETA for the interaction term between PRR coalitional capacity and immigration inflow across all clusters, which is the amount of change in the coefficient of this term when a cluster is suppressed (Belsley et al., Reference Belsley, Kuh and Welch2004, 27–28).

Figure 4. Changes in Bilateral Aid Allocation Before and After the Populist Radical Right’s Involvement in Government Coalitions.

Notes: Estimation was made with two-way fixed effects for each period via ordinary least squares. Robust standard errors were clustered in panel pairs. The solid line indicates the estimated coefficient for the interaction term between PRR coalitional capacity and immigrant inflow. The dotted lines indicate the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5. Regression Diagnosis via Jackknife Resampling.

Notes: The values of DFBETA were calculated as the amounts that the coefficient of the interaction term between PRR coalitional capacity and immigration inflow changes when a cluster is suppressed. The acronyms are ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 country codes.

Figure 5 shows that most of the 1504 clusters are associated with the DFBETAs close to zero. Approximately 10 clusters appear to deviate from zero but, except for the Austria–Turkey pair, are within the threshold of being influential:

![]() $\left| {{\rm{influencial}}\;{\rm{DFBETA}}} \right| \gt {2 \over {{\rm{sqrt}}\left( {\rm{N}} \right)}} = 0.0138$

(Belsley et al., Reference Belsley, Kuh and Welch2004, 28). These clusters are concentrated on the donor countries with substantial PRR coalitional capacity, including Austria, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. In these countries, the DFBETA oscillates around zero due to the perturbations in aid allocation created by the PRR parties both in and out of government but does not exceed the threshold in most cases. To confirm this, the model was reestimated by removing observations above the threshold from the data. The estimates showed that the key interaction term remained negative and statistically significant.Footnote

9

Taken together, the model performs consistently well across the data, suggesting that the result is not an artifact of particular influential clusters.

$\left| {{\rm{influencial}}\;{\rm{DFBETA}}} \right| \gt {2 \over {{\rm{sqrt}}\left( {\rm{N}} \right)}} = 0.0138$

(Belsley et al., Reference Belsley, Kuh and Welch2004, 28). These clusters are concentrated on the donor countries with substantial PRR coalitional capacity, including Austria, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. In these countries, the DFBETA oscillates around zero due to the perturbations in aid allocation created by the PRR parties both in and out of government but does not exceed the threshold in most cases. To confirm this, the model was reestimated by removing observations above the threshold from the data. The estimates showed that the key interaction term remained negative and statistically significant.Footnote

9

Taken together, the model performs consistently well across the data, suggesting that the result is not an artifact of particular influential clusters.

Anecdotal evidence

Lastly, anecdotal evidence is presented to suggest that considerable decreases in bilateral aid occurred in PRR-participating or -supporting governments under weak pluralistic institutions and substantial immigrant inflows. Evidence is found in Italy, Denmark, and the Netherlands with such qualifications.

During the 2000s, Italy’s aid budgets steadily declined under the coalition governments led by Prime Minister Berlusconi with the Lega Nord’s participation. Faced with increasing immigrants, the prime minister passed Law 189/2002 to reflect the stick of the carrot-and-stick approach linking aid and bilateral cooperation on emigration management and reduced aid (Cuttitta, Reference Cuttitta2010). In Denmark, upon its formation in 2011, the center-right minority government led by Prime Minister Anders Rasmussen with support from Thulesen Dahl’s Danish Freedom Party (DF), tightened immigration rules by rejecting poverty as the root-cause of migration and reduced aid to 16 countries in Africa and Asia (European Centre for Development Policy Management, 2013). The Netherlands’ Rutte coalition government, formed after the election in 2011 with support from Wilders’ PVV, announced the reduction of aid by one billion euros, as Wilders requested (Faure, Reference Faure2014). These instances suggest correlation between aid reduction and the PRR. More research is needed to establish a causal link between the two in light of institutional and sociocultural dimensions.

Conclusions

This study investigated PRR influence in bilateral aid amid concerns about a potential connection between the rise of the PRR and the reduction of aid allocation. By analyzing experiences in Western European democracies, this study demonstrated that the PRR uses a direct coalitional pathway to reduce aid to the recipients that fail to stem immigration into the donor countries. It further showed that punitive reduction intensifies in conjunction with the donors’ weak pluralistic institutions and the recipients’ heterogeneous sociocultural characteristics.

However, the study has limitations. It did not analyze public opinion as a potential confounder in the model (Abou-Chadi and Krause, Reference Abou-Chadi and Krause2020), because it was viewed as influencing aid through party systems and also because consistent survey data on aid and immigration were unavailable for a sufficiently large number of donor countries with varied institutional arrangements to evaluate the hypotheses. Nor did it examine aid by donors other than Western European countries. More elaborate research is needed to investigate the unaddressed issues.

Despite the limitations, this study offers a novel contribution to the literature on the PRR by integrating insights on the aid–immigration nexus, political strategies, and ideational profiles. The findings confirm that aid is an issue area, including crime and minorities, wherein PRR parties engage in the politics of punishment. They uncover that the PRR aid-reducing pressure is strategic, driven by horizontal and vertical differentiations vis-à-vis immigrant-sending foreign countries and inept domestic elites, respectively. The politics of punishment in aid is, therefore, a distinctive manifestation of the two differentiation strategies that are commensurate with the ideational profiles of nativism and anti-establishment.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000073.

Acknowledgments

An earlier manuscript was presented at the annual convention of the International Studies Association, April 6–9, 2021, online. The author thanks Deina Abdelkader, Ali Hager, Azusa Uji, and the journal’s editors and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. He is also grateful for the excellent research assistance of Sou Shinomoto, Sonia Ruiz Pérez, and Akira Kawase. This research was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS #18KK0037). All remaining errors are the author’s responsibility.

Competing Interests

This manuscript has not been published or presented elsewhere in part or in entirety and is not under consideration by another journal. I have read and understood your journal’s policies, and I believe that neither the manuscript nor the study violates any of these. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.