I IntroductionFootnote 1

Landlessness and the resulting poverty are major development issues in Bangladesh, not only because of the scarcity of land – since Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries on earth – but also due to the fact that land grabbing or illegal dispossession of land is frequent in Bangladesh and often results in landlessness. The institution of the judiciary has a key role to play in correcting this situation in Bangladesh. There is no denying that access to justice and the rule of law are key elements of sustainable and equitable development. Access to justice is foundational to people’s access to public services, curbing corruption, restraining the abuse of power, and establishing a social contract between people and the state (United Nations, 2019b).

In Bangladesh, there are many institutional weaknesses related to land administration and management which exacerbate the problems of illegal dispossession of land and land litigation. As land is one of the most important means of livelihood security in Bangladesh, improper and unfair litigation of land-related issues can exacerbate poverty, as well as affecting prospects for economic growth (Barkat and Roy, Reference Barkat and Roy2004).

The judiciary, by definition, has the prime role in solving land litigation issues. However, the judiciary has not been able to perform its due role with respect to land litigation in Bangladesh. A number of issues cause inordinate delay in the litigation procedure and create backlog of cases. In developing nations generally, deficiencies and institutional challenges relating to the judiciary further complicate issues related to land litigation, and thus affect economic growth and poverty (United Nations, 2019b). By contrast, where a judiciary functions effectively it can effectively mitigate irregularities and conflicts, and thus can play a critical role in ensuring economic growth and alleviating poverty.

Against this backdrop, this chapter aims to explore the current state and performance of the judiciary of Bangladesh and its possible impact on poverty and development by considering involuntary land dispossession litigation as an example. This chapter attempts to provide a narrative analysis of the process through which involuntary land dispossession takes place in the particular socio-economic and historical context of Bangladesh. Involuntary dispossession of land results in the economic outcome termed forced asset transfer. This chapter aims to examine how this outcome is influenced by the overall functioning of the judiciary in Bangladesh. Consequently, this chapter aims to scrutinise the interrelation between economic assets, human actions, and state institutions, and its possible impact on the overall trajectory of long-term development. Finally, this chapter aims to identify potential reform measures and agendas in relation to land dispossession litigation in Bangladesh.

II The Effectiveness of the Judiciary in Bangladesh: A General Assessment

A well-functioning civil justice system protects the rights of all citizens against infringement of the law by others, including by powerful parties and governments. An essential component of the rule of law is an effective and fair judicial system that ensures that the laws are respected and appropriate sanctions are taken when they are violated (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2015). In order to understand the current state of the effectiveness of the judiciary in Bangladesh, the following subsections set out a brief account of the structure of the judiciary and the degree of its fairness, the expeditiousness of judicial procedures, and the degree of independence of the judiciary from the executive branch of government.

A An Overview of the Structure of the Judiciary

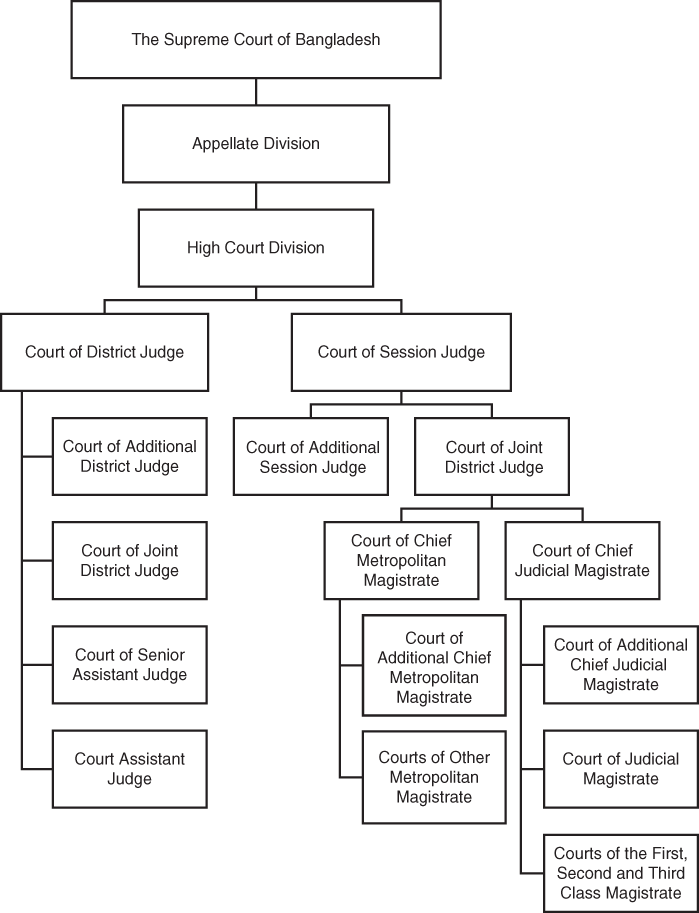

The current justice system of Bangladesh has its roots in both the traditional subcontinental justice system which was developed over centuries during the reigns of Hindu and Muslim rulers, including the Mughals, and the common law justice system introduced by the British colonial ruler in the subcontinent (Halim, Reference Halim2008). Moreover, the Constitution of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh lays out the structure of the judiciary, and has undergone multiple amendments since independence in 1971. Among these amendments, some have greatly influenced the structure, functions, and jurisdiction of the higher and lower courts. Currently, the judiciary of Bangladesh is composed of three adjudicative bodies: the higher judiciary, the lower judiciary, and specialised tribunals. The structure of the judicial system of Bangladesh is presented in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 The structure of the judicial system of Bangladesh.

The higher judiciary refers to the Supreme Court, which consists of the Appellate Division and the High Court Division.Footnote 2 The Appellate Division is the constitutional court, with no original jurisdiction. It hears appeals against: (a) High Court Division orders, judgements, decrees, or sentences involving constitutional interpretation, capital punishment, life imprisonment, and sentences for contempt; and (b) judgements or orders of specialised tribunals, such as the Administrative Appellate Tribunal and International Crimes. The courts that are subordinate to the Supreme Court – namely, the Appellate Division and the High Court Division – were established under Article 114 of the Constitution. The Civil Courts Act 1887 directs the subordinate civil courts, and the Code of Criminal Procedure guides the courts of magistrates and sessions. In the case of civil courts, there are five grades, including: Courts of Assistant Judge, Senior Assistant Judge, Joint District Judge, Additional District Judge, and the District Judge. The District Judge heads these courts for all districts except for the three Chittagong Hill Tracts districts.Footnote 3 There are also five classes of subordinate criminal courts: the Courts of Session, Metropolitan Magistrate, Magistrate of the First Class, Magistrate of the Second Class, and the Magistrate of the Third Class. In the Court of Sessions, the District Judges are empowered to function as Session Judges. In addition, the Government of Bangladesh has enacted the Village Court Act 2006 and has taken the initiative to activate village courts at the union level (UNDP and Government of Bangladesh, 2019). However, village courts have yet to be established throughout the country. When they are, their jurisdiction will be very limited, and they will deal only with civil issues.

The Constitution of Bangladesh guarantees human rights and freedom, equality, and justice and the rule of law for all citizens (Huda, Reference Huda1997). In agreement with the Constitution, there are three basic requirements of a judicial system: fairness (which includes various dimensions); the effectiveness and the expeditiousness in the procedures; and the independence of the judges. The available evidence on various measures of the effectiveness of the judicial system in Bangladesh is discussed in the following subsections.

B Degree of Fairness of the Judiciary

Access to justice is one of the basic principles of the rule of law. If access to justice is hindered and any form of discrimination or bias persists in the process of delivering justice, this can undermine the voice and rights of the people. According to an estimate by the OECD, around 4 billion people around the world live outside the protection of the law, mostly because they are poor or marginalised within their societies. The lack of legal accountability propels local corruption and diverts resources from where they are needed the most. In addition, women are particularly affected by legal exclusion as they often face multiple forms of discrimination, violence, and sexual harassment. Thus, access to justice and fairness of the judiciary are essential to enable the basic protection of human rights (OECD-OSF, 2016).

In Bangladesh, there is a lack of well managed data regarding the various features and functioning of the judiciary. Thus, in order to capture some dimensions of the fairness of the judiciary, in the analysis in this section, three indicators are considered from the World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law IndexFootnote 4 (WJP, 2019): ‘people can access and afford civil justice’, ‘civil justice is free of discrimination’, and ‘civil justice is free of corruption’. It should be noted that the selected indicators are related to civil justice. This is because the main focus of this chapter is land dispossession litigation, which falls under the jurisdiction of civil courts, and this chapter principally intends to highlight the situation of civil justice when discussing the performance of the judiciary.

It should be noted that the WJP Rule of Law Index contains a number of limitations. First, the index has been constructed based on a significant proportion of subjective information given by both experts and the general public. Second, the opinions and perceptions of the individual respondents may vary to a great extent across time and geographic region. Despite these limitations, the WJP Rule of Law Index 2019 provides an opportunity to examine the relative position of Bangladesh compared to another 125 countries. Out of the total 126 countries in the index, roughly 28 can be broadly categorised as developed countries and the rest as developing countries.

The first indicator ‘people can access and afford civil justice’ measures the accessibility and affordability of civil courts, including whether people are aware of available remedies and can access and afford legal advice and representation. It also measures whether people can access the court system without incurring unreasonable fees, or facing procedural hurdles or physical and linguistic barriers. The second indicator ‘civil justice is free of discrimination’ measures whether the civil justice system discriminates in practice based on socio-economic status, gender, ethnicity, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, or gender identity. The third indicator ‘civil justice is free of corruption’ measures whether the civil justice system is free of bribery and improper influence by private interests (WJP, 2019).

Bangladesh ranks 106 among the 126 countries for the ‘people can access and afford civil justice’ indicator of the WJP 2019, with a score of 0.4498, compared to the median score of 0.5637. Likewise, for the ‘civil justice is free of discrimination’ indicator Bangladesh’s relative position is 115 among the 126 countries. Again, its score is 0.3613, relative to the median score of 0.5623. Finally, Bangladesh ranks 100 among the 126 countries for the ‘civil justice is free of corruption’ indicator, with a score of 0.3674, in comparison to the median score of 0.5224. The data show that Bangladesh’s relative performance in all of the three areas with regard to the fairness of the judiciary is in the bottom quintile or the bottom decile of a set of 126 countries.

C Expeditiousness of the Judicial Procedures

One of the fundamental aspects of the effectiveness of the judiciary is the expeditiousness of the judicial procedures. The well-known legal maxim ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ is based on the principle that if redress is not available in time and there is little hope of resolution, it may well be regarded as there being no redress at all. This principle forms the basis of the right to a speedy trial and similar rights which are meant to expedite the legal system. Thus, the expeditiousness of the judicial procedures is often considered to be a critical element for ensuring an effective justice system. If the judicial system guarantees the enforcement of rights, creditors are more likely to lend, businesses are dissuaded from opportunistic behaviour, transaction costs are reduced, and innovative businesses are more likely to invest (OECD, 2013; IMF, 2017; World Economic Forum (WEF), 2018; World Bank, 2017). The relative picture regarding the current degree of expeditiousness of the judicial procedures in Bangladesh is discussed here.

The ‘civil justice is not subject to unreasonable delay’ indicator of the WJP Rule of Law Index measures whether civil justice proceedings are conducted and judgements are produced in a timely manner without unreasonable delay. It can be observed that Bangladesh’s performance is again particularly poor for this indicator, ranking 121 out of the 126 countries in 2019, with a score of 0.1917, compared to the median score of 0.4384.

A closer examination of the primary data reveals that the case backlog is especially acute in the subordinate or district courts of the country.Footnote 5 The total civil case backlog at the end of 2018Footnote 6 was 1,321,038, and the number of total cases including new cases was 1,396,350. Among these, only 58,234 cases were resolved, which is about 24 times less than the total cases. A comparatively smaller number of cases (6,001 cases) were transferred or received a stay order from the higher courts, and also a few (1,716 cases) were resolved through Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). It can also be observed that the total number of civil and criminal cases has increased overtime in the High Court and Appellate Division.

A number of factors may have propelled the growth of the total number of pending cases in the higher and subordinate lower courts of Bangladesh. One of the main reasons behind the growth of pending cases in the last decade is the lack of capacity and resources in the judiciary. The total number of judges compared to the total population and number of cases is still quite low in Bangladesh. According to the annual report of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, there were a total number of seven judges (including Chief Justices in the Appellate Division and 95 judges in the high Court) in 2018 (The Supreme Court of Bangladesh, 2019), which shows the lack of capacity of the overall system. Similarly, the total number of approved posts of judges for the lower courts was 1,655, of which 387 remained vacant until 2017 due to delays in the recruitment process (Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2017).

In addition, in Bangladesh, civil cases are generally based on documented evidence and oral evidence is only taken as a supplement to documents. The civil courts still follow the Evidence Act of 1872, the Civil Courts Act of 1887, the Code of Civil Procedure of 1908, and some other special laws that are applicable to the operation of civil cases. The common practice of examining witnesses in civil courts involves stating the whole case line by line, with the judge writing every statement out by hand. If this manual recording is not followed, then further clarification is required according to the Code of Civil Procedure 1908.Footnote 7 For this reason, the present nature of peremptory hearings consumes a considerable amount of time and the dependence on manual paperwork contributes to increasing case backlog (Tahura, Reference Tahura2015). Likewise, as mentioned earlier, along with a shortage of judges, a number of systematic problems compound the backlog problem, including poor investigation by the police, too many adjournments at courts, an absence of witness, the lack of capacity of legal professionals, a lack of coordination among different government departments, and the unwillingness of some lawyers to settle the case within a short time (Tahura and Kelly, Reference Tahura and Kelly2015; The Supreme Court of Bangladesh and UNDP, 2015; Transparency International Bangladesh, 2017; Rahman, Reference Rahman2018; The Justice Audit Team, 2018).

Moreover, political turmoil and deterioration of the rule of law over time has caused an increase in the number of cases in recent years (Sarkar, Reference Sarkar2015). Besides, according to Bangladesh Bank, the central bank of Bangladesh, more than 55,500 cases involving default loans were pending with the courts as at June 2018 (The Daily Star, 2018b). Furthermore, the Vested Property Return Act of 2013 came as an additional complicating factor as it allowed the Government to confiscate the property of individuals considered to have acted as an enemy of the state during the India–Pakistan war of 1965 (Yasmin, Reference Yasmin2016). From 2013 to 2016, the Government of Bangladesh activated special tribunals throughout the country to restore vested property. Since 2016, claims for vested property have been managed by the formal judiciary.

The upshot of the above situation is that the judicial system of Bangladesh is increasingly burdened with a backlog of cases due to various socio-economic, political, and historical factors. A lack of initiative to compel clerks, advocates, litigants, or witnesses to comply with the due codes, rules, and processes leads to inordinate delays at the different stages of the litigation procedure. However, along with the lack of any adequate initiative to improve the performance of the judiciary, institutional failures in other areas – especially with respect to land management, default loans, and the overall deterioration of rule of law – are also producing a significant growth in the backlog and the slower disposal of cases. This growing backlog and slowly disposed cases are seriously hampering the overall performance of the judiciary. This scenario especially holds in the three major business and administrative hubs of Bangladesh, namely Dhaka, Chittagong, and Khulna. As a result, individuals, businesses, and private investors are increasingly facing uncertainties and challenges. Ultimately, the low level of expeditiousness of judicial procedures in Bangladesh is a severe impediment for the overall business climate and competitiveness of the country.

D Independence from the Executive Branch of the Government

Independence of the judiciary is based on the axiom of the separation of powers: the judiciary should remain separate and independent from the executive and legislative branches of government. The independence of the judiciary depends on certain conditions like the mode of appointment of judges, security of their tenure in office, and adequate remuneration and privileges. Such independence enables the judiciary to perform its due role in the society, thus inspiring public confidence in it. The independence of civil justice thus requires a set of detailed rules and procedures to ensure that a dispute will be treated in a neutral way, without biases in favour of any party (OECD, 2015).

In Bangladesh, despite a constitutional mandate for the separation of the judiciary from the executive organs of the state, the recruitment of subordinate court judges used to be conducted by the Bangladesh Public Service Commission (Islam, Reference Islam2014). However, the government-versus-Masdar-Hossain case in 1999Footnote 8 produced a landmark judgement regarding judicial independence. Nevertheless, until 2006, the judgement remained largely unimplemented. In 2007, the caretaker government took initiatives to implement the judgement.Footnote 9 This removed the impediment to the separation of the lower judiciary from executive control and the appointment of judicial magistrates (Biswas, Reference Biswas2012). However, the ordinances of the caretaker government have not yet been fully enacted and the judiciary has yet to be completely separated from the influence of the executive branch. The Law and Justice Division of the Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs has the constitutional authority to manage the appointment, transfer, resignation, and removal of the judicial officers, judges,Footnote 10 and additional judgesFootnote 11 of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh and the Attorney-General.Footnote 12 In addition, the appointment of the next senior Judge of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court as the Chief Justice is also the responsibility of the divisionFootnote 13 (Law and Justice Division, 2019). This leaves the judiciary somewhat vulnerable to political manoeuvring and vested interests (Huda, Reference Huda2017; Islam, Reference Islam2017; The Daily Star, 2018c).

The ‘civil justice is free of improper government influence’ indicator of the WJP Rule of Law Index measures whether the civil justice system is free of improper government or political influence. Bangladesh ranked 76 out of 126 countries in 2019, with a score of 0.4412, compared to the median score of 0.4907. This shows that Bangladesh has an average level of performance in terms of judicial independence. Overall, there is still much room for improvement with regard to the complete separation of powers in Bangladesh.

An independent and strong judicial system is an essential element of a free, fair, and just society and an efficient economy. If the independence of the judiciary is undermined, it further aggravates many other issues and concerns. For example, when it comes to ensuring the legal accountability of government officials, the judiciary can exercise suo muto (by own initiative) power to uphold justice (Mollah, Reference Mollah2010).Footnote 14 Again, the judiciary can ensure checks and balances in a society through judicial activism. However, these practices will not be effective in the absence of an independent and well-functioning judiciary.

III The Effectiveness of the Judiciary in Bangladesh: The Case of Land Litigation

Understanding the effectiveness of the judiciary encompasses several dimensions. This chapter adopts land litigation in the civil courts of Bangladesh as a case study to explore the effectiveness of the judiciary. This section provides a brief account of the nature of land conflicts, the related litigation process, as well as the methodology and major findings of a qualitative appraisal of effectiveness of the judiciary with respect to land litigation in Bangladesh.

A Land Conflicts and Litigation

It should be noted that the terms land dispossession and land grabbing are sometimes used interchangeably in the Bengali language. In general, land grabbing is synonymous with large-scale land appropriation, usually by large corporations (Rudi et al., Reference Rudi, Azadi, Witlox and Lebailly2014; Semedi and Bakker, Reference Semedi and Bakker2014; Suhardiman et al., Reference Suhardiman, Giordano, Keovilignavong and Sotoukee2015; Tura, Reference Tura2018). As mentioned earlier, Bangladesh is a land-scarce country and due to extreme population pressure, large-scale land appropriation by private companies does not occur on a scale compared to some other countries of the world where land constraints are not as prominent. However, the Government sometimes acquires sizeable quantities of land for special economic zones or other similar economic activities. What appears to be the major land issue is forced or fraudulent takeovers of land of relatively small or moderate size. For this reason, the nature of land grabbing in Bangladesh may best be described as the involuntary dispossession of land. This chapter therefore centres on cases of such dispossession and looks at the effectiveness of the judiciary in resolving them.

1 Land-Related Conflicts

In local dialect, land grabbing reflects the notion of bhumi dakhal, which can be literally translated as ‘to take control of land’. In the Bangladeshi context, land grabbing means forceful dispossession. In its most basic form, land ownership is defined by the physical act of occupying a piece of land. Essentially, dakhal is an outcome of the relations between different sources of power and authority, from large landowners, local strongmen, and goons (mastaans) to influential government officials (military and civil service both), elected officials, and national politicians. Thus, grabbing or dakhal is the result of continuous negotiations between these different actors (Suykens, Reference Suykens2015).

Land grabbing or involuntary dispossession may occur for many reasons. Adnan (Reference Adnan2013) has explained that very often, when peasants are not willing to sell their piece of land due to either emotional attachment to ancestral holdings or its location specificity, involuntary dispossession or dakahl involves use of force through extra-economic and non-market mechanisms, including violence and use of state machinery. In recent years, increasing amounts of land have been taken out of agricultural production as a result of fast urbanisation and industrial expansion. These takeovers are mostly done by realtors for housing, by corporate interests for commercial use, and by the state for military or industrial use.

Feldman and Geisler (Reference Feldman and Geisler2012) examined land grabbing in Bangladesh and viewed such seizures through the lens of displacement and land encroachment. Their study examined two different but potentially interacting displacement processes. The first takes place in the char, riverine and coastal sediment regions, which are in a constant state of formation and erosion and consequently are ripe sites for contestation and power play. In this region, mainly small producers are uprooted from their rich alluvial soils. The second displacement process is observed in peri-urban areas where elites engage gangs and corrupt public servants to coerce small producers into relinquishing titles to their ever more valuable lands. Thus, there are both in situ displacements where people may remain in place or experience a prolonged multi-stage process of removal and ex situ displacements where people are brutally expelled from their homes, communities, and livelihoods.

It is evident that where landholdings are small and everyday subsistence is precarious, even a limited amount of land dispossession at the expense of those whose subsistence depends on agriculture is an engine of landlessness and chronic poverty. This situation in Bangladesh therefore highlights the role of the state, especially the role of the judiciary and its sanctions regarding involuntary land dispossession. During the fieldwork for the present study,Footnote 15 a number of sources of land-related conflicts in Bangladesh were identified. These conflicts are broadly depicted in Box 9.1.

Box 9.1 Common types of land conflicts in Bangladesh

| Types of land conflicts | Victim | Nature of land | Source of conflict |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict with the state/government | Private owners | Private land | Involuntary dispossession due to land acquisition for state-led development activity |

| Conflict with large companies | Government, poor individuals, indigenous community | Private land, community land, public property, or khas land, hills, rivers | Involuntary dispossession due to land acquisition for commercial activity or private gain |

| Conflict with smaller companies | Individuals/indigenous community | Private land, community land | Involuntary dispossession due to land acquisition for commercial activity or private gain |

| Conflict with elites/politicians/goons at the local level | Mostly poor individuals with less economic and socio-political influence/capital, absentee owners | Private land, community land | Involuntary dispossession due to miscalculations or mistakes in the land survey; elite capture due to loopholes in or undue misinterpretation of the existing laws or regulations |

| Conflict with neighbours and family members | Individuals | Private land | Involuntary dispossession due to miscalculations or mistakes in land surveys, fraudulent behaviour, ambiguity in inheritance procedures, and informality in inheritance distribution |

Note: The type and nature of land, victims, and sources of conflict vary based on different circumstances.

The major types of land litigation can be divided into a number of categories, including: a declaratory suit, cancellation of a deed, a partition suit, recovery of khas possession, eviction of a tenant, a money suit, a pre-emption case, pre-emption under Mohammedan law, a vested property release case, a land survey tribunals case, a mandatory injunction, an arbitration suit, succession cases, and other miscellaneous cases. If the suit valuation ranges from Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) 100,000Footnote 16 up to BDT 200,000, the jurisdiction for litigation will fall under the Court of Assistant Judge. Similarly, if the suit valuation ranges from BDT 200,001 up to BDT 400,000, it will fall under the Court of Senior Assistant Judge. Finally, if the suit valuation is BDT 400,001 and higher, the jurisdiction for litigation will fall under the Joint District Judge. Typically, land litigation in Bangladesh follows the workflow of civil litigation (see Figure 9.1 for the detailed hierarchal structure of the judicial system of Bangladesh).

2 Land Litigation in the Formal Judicial System

As suggested by Figure 9.2, the first step of any civil litigation process in Bangladesh begins with the filing of suit to the sherestadar, a court officer. The suit is then entered into the register of suits. The defendant is informed about the case and provided with a copy of the plaint, and thus summons is served. Then if the defendant appears at the court with his written statement, the court tries to mediate between the parties. If the mediation fails, the court fixes a date for a first hearing. At the first hearing, the court examines the claims of the parties and frames the issues. After that, the court announces the date for a peremptory hearing and orders the parties to submit a list of witnesses. The peremptory hearing is followed by a further hearing and presentation of the arguments. Subsequently, the court pronounces the judgement on the day of the trial or later at a fixed date. Ultimately, the court may pass an order. However, if the defendant does not appear before the court throughout the overall litigation process, then an ex-parte hearing takes place. In this case, the evidence is recorded and an ex-parte order is given. Finally, based on the argument and evidence, the court draws up the decree irrespective of the appearance or absence of the defendant at the hearings.

Figure 9.2 Procedure of land litigation in Bangladesh.

Thus, a plaintiff usually first goes to the muhuri to have an appointment with a lawyer. The lawyer then files the case and sends it to the court. The case is then recorded in the sheresta by the sherestadar and summons is issued through the nezarat by the nazir. After that the date of the hearing is usually managed by the peshkar of the court.

B A Qualitative Appraisal of Judiciary Dysfunction in Land Matters

1 Methodology

The purpose of the qualitative analysis in this chapter is to focus on the inherent political economic issues of the factors and processes underlying land dispossession litigation and their outcomes in terms of poverty and well-being in the particular social–historical instance of Bangladesh. The analysis is based on a rich variety of primary data collected through a number of detailed case studies, key informant interviews, focus group discussions, and participant observations conducted between April and July 2019. The victims of the case studies were identified with the help of local activists and the District Lawyers’ Association. References from the case studies will be made in this chapter with the help of coded names. In order to understand the political economy of land dispossession litigation, two areas of Bangladesh, which display different characteristics, were selected for the study: Anwara and Gazipur upazila. The first study area is a heavily industrialised area located near the major sea port, and the second area is situated near the densely populated capital.

Anwara upazila is located in Chattogram Division of Bangladesh. It has an area of about 164.13 square kilometres. Anwara is one of the most heavily industrialised areas of Bangladesh. It is the location of a number of companies, including: Karnaphuli Fertilizer Company Ltd, Karnaphuli Polyester Products Company Limited, Chattogram Urea Fertilizer Limited, and the Korean Export Processing Zone, which is financed by the Korean Young One Corporation. The Korean Export Processing Zone is the largest private export processing zone in the country, spanning 2,492 acres. Korean Export Processing Zone is located on the south bank of the river Karnaphuli, opposite to Chattogram International Airport and close to the country’s major sea port at Chattogram. In addition, the Government of Bangladesh is also building an underwater tunnel under the Karnaphuli River which is going to be connected to a six-lane highway. On the other hand, Gazipur Sadar upazila is located in Dhaka division. It has an area of 446.38 square kilometres. There are also a number of water bodies near Gazipur and the Sadar upazila is home to a number of historical monuments, relics, archaeological heritage sites, and national parks. Moreover, Gazipur is situated right next to the capital and city dwellers can easily plan a day trip to the location. For this reason, the area is a popular destination for tourists and recreation seekers. Furthermore, the proximity to the capital Dhaka has turned Gazipur into a hub of manufacturing and industrialisation. The Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation (BSCIC) industrial areas in Tongi and Konabari alone host a plethora of large and medium-sized industries.

Some secondary data related to case statistics have also been collected from a variety of documentary sources and from the office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh. At the same time, the study draws insights and information from a rigorous review of the relevant literature.

2 Findings

There are a number of possible causes of institutional inefficiencies in the judiciary. However, we focus here only on the causes of institutional inefficiencies in relation to involuntary land dispossession litigation. Based on the analysis of primary data, these inefficiencies can be attributed to various factors, including: the ambiguity of procedural laws; poor updating and preservation of land records; a shortage of qualified personnel and misallocation of roles; unequal access to justice; delays in procedures; and influence peddling and power asymmetries. A brief account of the causes of institutional inefficiencies in the judiciary with respect to involuntary land dispossession litigation is presented in the following subsections.

I Actors Involved in the Land Litigation Process.

The analysis of the qualitative data reveals that different actors are involved at each level of involuntary land dispossession litigation, with different interests and degrees of power or influence (Box 9.2). However, it is worth noting that the actors are connected to each other through various degrees of contest and coalition. The identified actors can be grouped in four categories: state actors, non-state actors, internal actors, and external actors.

Box 9.2 Categories of actors involved in the land litigation process in Bangladesh

| State actors | Non-state actors | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal actors | Police Public prosecutors Judges Sherestadar Nazir Peshkar | Muhuri Lawyers Plaintiffs Defendants |

| External actors | Union parishad chairmen and members Tehsil offices Kanungo Sub-registrars ACs Land Upazila Nirbahi Officer Deputy Commissioner (DC) offices Politicians of the ruling party (holding public office) | District Lawyers’ Associations District Bar Associations Local brokers Local influential people Local businessmen Politicians of the opposition party |

Note: The above categorisation and the position of the actors in the matrix may sometimes vary based on different contexts.

State actors refers to actors who hold positions in government offices and who have a role in land litigation in one way or other. Many of these actors do not have any direct authority over the litigation process: for example, the union parishad chairman has only informal influence over the process. Although the union parishad chairman is not directly a part of the formal litigation process, he can influence the legal support-seeking behaviour of common citizens. On the other hand, non-state actors are those who have a stake in the litigation process but have no official authority to influence the outcome of the litigation. For example, as a professional body the lawyers’ association plays an important role in identifying the appropriate lawyer for the litigation. Usually, the leader of the lawyers’ association has informal influence over the proceedings of the court as the support of the leaders of the lawyers’ association may help to speed up the litigation process.

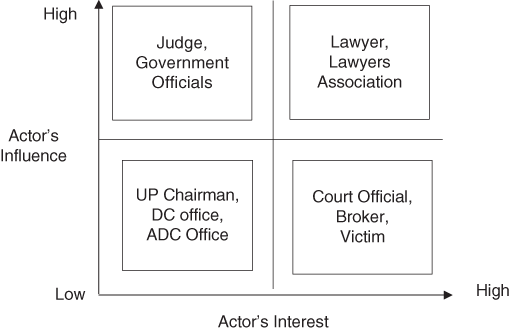

Similarly, there are brokers active in the court area who can connect a service-seeker to an influential lawyer who might not be known to the service-seeker otherwise. These brokers are people who live on their network with court staff and lawyers. However, while monetary transactions take place between the different actors involved in the litigation process, among these payments only the court fee and lawyer’s fees are officially due, while the rest are unofficial fees. In addition, lawyers are also active in national politics and many lawyers aspire to a career in politics. These kinds of intangible interests also play a role in influencing the litigation process. Although the power and influence of the key actors in the land litigation process may vary depending on the context, a general scenario of the interplay between the interests and influence of the main actors is presented in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 Influence and interest matrix of actors.

Note: The above categorisation and the position of the actors in the matrix may sometimes vary based on different contexts; ‘government officials’ in this figure refers to the formal state actors from Box 9.1 (i.e. police, prosecutors, sherestadar, etc.).

Figure 9.3 shows that the judge and other court officials have a high degree of influence over the proceedings, but they also have a low degree of interest in them because they are overburdened with cases. However, the lawyer and the lawyers’ associations have a higher interest and relatively higher influence. If they want, they can increase or decrease the speed and cost of the process. On the other hand, petty court officials like peshkar and serestadar have a high degree of interest because they are usually paid in an unofficial manner by clients for their support and services. On the other hand, they do not wield a high level of control over the litigation process: they have a facilitating role but cannot determine the outcome of that process.

II The Ambiguity of Procedural Laws.

The current structure of the judiciary also bears the historical legacy of the colonial period and is still heavily guided by the institutional traditions of the British era. For this reason, sometimes the laws, rules, and procedures regarding the civil litigation are not clearly articulated in the local language or contain inherent flaws. One senior lawyer explained during an interview that, after a number of amendments, the current law states that a defendant will receive a maximum of three chances to respond to a summons. However, the law does not clarify what will happen after the three opportunities are over. It is unclear whether the case will then become an expert judgement or an unreported right. In sum, the cumulative legacy of the past creates difficulties for the general public to effectively comprehend, access, and use the judicial system.

III Poor Updating and Preservation of Land Records.

Land management in Bangladesh is done by several government agencies, among which coordination is almost non-existent.Footnote 17 Mismatches in historical government records and personal records are a major source of institutional inefficiency as these create inconsistency regarding the identity of the landowner and the size of the landholding at stake. In the case of a land ownership transfer, the sub-registrar office registers the new deed in the book of records (balam bohi). In Anwara, there are two separate index books for accessing these balams. They are ordered according to the names and the daag or plot number. However, as these records are handwritten and manually preserved, they are prone to damages and accidents. Furthermore, the sub-registrar offices do not have access to the khatian or Record of Rights (RoR), which is managed by the AC Land office. It is therefore quite difficult for a sub-registrar to verify the information regarding the ownership, and this again contributes to creating further conflicts and backlogs. In addition, when it comes to the transfer of ancestral property, most contracts are informal in nature, which creates fertile terrain for conflicts.

IV A Shortage of Qualified Personnel and Misallocation of Roles.

There is lack of professional and well-trained civil lawyers in Bangladesh. A land litigation process requires a substantial amount of knowledge and expertise as the relevant documents contain sophisticated and complicated information. Nonetheless, the key informant interviews and focus group discussions reveal that most of the time lawyers are not adequately trained to successfully manage land litigation. In addition, the newly recruited judges and workforce in the judiciary may also not be well equipped to deal with complicated cases. As a result, hearings become lengthy, and this ultimately adds to the overall backlog. Moreover, a lack of resources and a lack of proper infrastructure are another major cause behind the huge case backlog in Bangladesh. Finally, during the fieldwork, one of the judges mentioned that people in the different administrative tiers often make wilful mistakes (e.g. misreporting and fraudulent behaviour by local people or rent seekers) and one of the main causes of land disputes in Chattogram is mistakes made during the Bangladesh Survey.Footnote 18 This judge also suggested that government officials are not doing their part, thus forcing people to file cases to obtain a correction of the mistakes made in the survey. Consequently, the judges now have to bear the extra workload involved in correcting petty mistakes.

V Unequal Access to Justice.

In recent years, the Government of Bangladesh has been acquiring land for the implementation of a number of large-scale or mega infrastructural projects. In many instances, poor and illiterate people have fallen victim to land dispossession in such cases, due to a lack of proper knowledge regarding their legal rights. On top of this, there is also a lack of adequate state-supported legal services for ordinary citizens. One of the respondents from Anwara described how about two years ago, the Government acquired a large amount of land in order to build the Karnaphuli Tunnel. As a result, around 300–400 households may have been evicted from their ancestral land. A good number of these evicted families have filed a case against the Government. However, according to the law of the acquisition of land, if a person files a case against the decision of a government acquisition, he/she cannot receive any compensation until the litigation is over. In the absence of adequate state-supported legal aid facilities, local brokers easily mislead illiterate and helpless people to file such cases and repeatedly seek to obtain various rents from both the victims and lawyers. This is due to the fact that landowners, or the victims in general, lack the proper information, and lawyers and brokers are usually more informed. As a result, lawyers and brokers exploit the lack of knowledge of the owners or victims.

VI Delayed Procedure.

According to one of the senior lawyers of the Chattogram District Bar, there are often undue delays in the issuing of notices. Nevertheless, when the date of the hearing finally arrives, it is quite common for either the plaintiff or the defendant not to be present in the court room. This unnecessarily prolongs the case time. The judge has to set another date for the hearing, and this occurs repeatedly. In this scenario, a judge can declare a one-sided verdict and stop the process. However, some respondents believe that in recent years, as judges usually want a full hearing in the presence of all parties to a case, and as these hearings are often piecemeal in nature, this again is causing a backlog and delays. A number of respondents mentioned the prevalence of numerous such dilatory tactics in the courts.

VII Influence Peddling, Fraud, and Corruption.

When asked about the main reason for the case backlog and delays in the process of land litigation, each of the key actors in the overall land administration and litigation process claimed that they are doing their part and that the other parties involved are to be blamed for the existing problems. During interviews, the local government authorities largely blamed the judges and lawyers, while one of the local judges blamed the local government authorities and lawyers. The latter mentioned that the executive influences the judiciary in a number of ways. Similarly, during the interviews, the lawyers mainly blamed the judges and also the local government officials. Behind this game of responsibility shifting, there is a complex dynamic of power and influence that affects the overall scenario of land dispossession litigation in Bangladesh.

Corruption and rent sharing is one of the propelling forces behind the overall institutional inefficiency of litigation system of Bangladesh in respect of land dispossession. Sometimes people are forcefully evicted or compelled to sell their land at an unfair price to large companies due to widespread corruption (i.e. bribery, extortion, cronyism, nepotism, patronage, etc.). During the fieldwork, one of the respondents in Anwara explained that large companies first buy small amounts of land in a scattered fashion and then they start pushing the surrounding land owners to sell their lands to them. In most cases, these big companies have established a good understanding with the local government officials and the law enforcement agency. For this reason, the local land owners are often compelled to sell their land off to them at an unfair price, and sometimes are even forcefully evicted. Local small landholders are not strong enough to go up against these big companies. They often do not report malpractices or seek any redress, out of fear.

Moreover, local government officials sometimes exercise their authority to seek undue rent. In one of the case studies,Footnote 19 Mr X, a resident of Anwara, explained that a pond that is part of his ancestral property was mistakenly recorded as khas land or government-owned land during the time of the Pakistan Survey.Footnote 20 Although his father had ownership of this pond according to the Cadastral Survey (CS),Footnote 21 he had to file a case and go through the costly litigation process to recover his claim, which took almost three years. Finally, the verdict was in his favour and he went to land office and applied for mutation. However, the upazila office disagreed to act upon the verdict and gave away the lease to another company. Mr X went to the DC and requested him to solve the matter. The DC ordered the Thana Nirbahi Officer (TNO) and AC Land to look into the matter. Even after that move, the problem was not solved, and eventually, Mr X had to go to the High Court. Up until the time of interview, he could not obtain a hearing data.

In addition, Anwara upazila is one of the most unique areas in Bangladesh from the viewpoint of social and demographic features. According to the locals, around 72% of the inhabitants are followers of the Hindu religion, while all other upazilas surrounding Anwara are Muslim-dominated. As a result, there is constant tension between the Hindus and Muslims over the ownership of land. It was also observed that women in general face greater challenges in seeking justice or redress. However, no matter which religion one follows, it is usually the poor and underprivileged segment of the society which is the victim of the worst forms of involuntary land dispossession. In one of the case studies,Footnote 22 Mr Z mentioned that once his grandfather rented part of his ancestral land to a Muslim farmer for share cropping. Later, when his grandfather became old, that farmer forcefully took over the land. Mr Z’s family went to the local authorities but failed to obtain any redress. Mr Z claimed that this is because he belongs to a religious minority in his community. Eventually his family filed a case; the case has been pending in the court for almost 12 years.

In one of the case studies from Gazipur, Mr A reported that his cousin fraudulently sold his land without his consent. When Mr A went to the shalish for redress, his cousin’s husband, who is a dominant political leader, threatened him and influenced the shalish through bribery. There were even instances of intimidation and vandalism. The local police even arrested Mr A instead of the perpetrators. He was in jail for about two months. After getting bail, he filed a case. There was a verdict five years ago which according to Mr A was distorted, and he did not appeal due to his poor economic condition.

VIII The Problem of Illegal Occupancy.

It is often the case that absentee owners or migrants face special problems regarding their land or property. The absence of the owner creates room for illegal occupancy by others. Moreover, if the owner is absent during land surveys, and if he does not claim possession, other people can provide incorrect information to the surveyor and change the ownership in the government land records. In one of the case studies,Footnote 23 Mr D from Gazipur mentioned that his father’s uncle had claimed false ownership of his property during his absence as a migrant worker. Mr D came back from abroad and filed a case, which has been pending for around two years now. Most of the time, the defendant, who is a local political leader, has not been present at the hearing. According to Mr D, money plays a vital role throughout the litigation process. From lawyer to muhuri, everyone demands money every time there is a hearing date. This scenario was repeated in a number of other case studies. Mr C from Gazipur was also a migrant worker, and in his case,Footnote 24 it was his uncle who deprived him of the proper share of his ancestral land. His case has been pending in the courts since 2010. According to Mr C, frequent transfers of judges, excessive bureaucracy in the court room, and political influence hinder a fast disposition of the cases.

Similarly, during the absence of Mr Y, a migrant worker from Anwara, a group of people claimed false possession of his property on the occasion of the Bangladesh Survey.Footnote 25 When he learned about this issue, he filed a case at the District Court and the court ordered the correcting of the mistake in the Bangladesh Survey. The opposite party in his case appealed against the verdict at the High Court. According to him, there might be some kind of collusion between the lawyers of both parties as none of them wants to end the case soon. He believes that the peshkar, lawyer, and muhuri are all informally connected and have conspired to lengthen the duration of the case.

3 What Do We Learn from the Qualitative Appraisal?

The above-mentioned institutional inefficiencies with respect to land dispossession litigation are caused by an increasing number of errors and petty issues that are repeated on a regular basis. While many of these petty issues can be resolved through effective collaboration between the actors, in reality, the land administrative bodies, judiciary, and law enforcement agencies tend to delay in resolving the issues, and even reproduce similar scenarios in some instances. This is because these issues and problems regarding land dispossession litigation generate a comparatively small amount of rent. However, this rent increases significantly when it is generated multiple times and over a long period. This creates an incentive for the major actors to reproduce the overall scenario of institutional inefficiency. For this reason, the actors may sometimes have a deliberate or spontaneous understanding among themselves to act together. The higher the number of interactions between different parties the higher the transaction costs, and thus, the accumulation of rent keeps growing. Thus, the major motivation behind keeping this inefficient system alive is the reality of huge rent generation and rent sharing across the major actors, which is the result of an auto-reproducible, strong but lower level of equilibrium. This strong equilibrium persists because none of the actors have the incentive to break it.

In this overall process, there may be rent sharing only among the actors within the judiciary, rent sharing among the actors in the judiciary and different external actors, and also rent sharing only among the external actors themselves. In the specific case of involuntary land dispossession, there can be delays in several steps of the overall litigation process. Although lawyers or defendants may sometimes attempt to create undue delay, the judges can play a major role in speeding up the hearings, and ultimately reaching a verdict within the time specified in the law. However, the proper implementation of the verdict is also important and the land administration authority here has the major influence, because local-level political leaders and law enforcement agencies usually tend to cooperate with the DC office or subsequent local government offices. Thus, it is evident that the state institutions have the major role to play in either promoting justice or prolonging institutional inefficiency in the judiciary in respect of involuntary land dispossession litigation in Bangladesh.

Nevertheless, it is imperative to note that all of these actors act within a context-specific environment and, given the reality, each individual is bound by their own circumstances. As a result, these actors are influenced by the context-specific actions of others and consciously or subconsciously iterate their process of decision-making at each stage of the overall process. Thus, it is not only the issues within the judiciary that slow the performance of the judiciary but also external factors. Since institutional inefficiency and corruption in other areas affect the overall functioning of the judiciary, the judiciary alone cannot solve these issues. A generic focus on upgrading only the capacity of the judiciary will not be sufficient to solve these issues in Bangladesh.

IV Conclusion

Institutional norms in a society are often dictated by the overarching socio-political and historic factors. The analysis in this chapter shows that the institutional inefficiency in the judiciary of Bangladesh has been an outcome of a longstanding interplay between social, historical, political, and economic factors which have accumulated over the years. In the particular case of Bangladesh, this accumulation of institutional inefficiency has created a spontaneous and auto-reproducible strong but lower level of ‘equilibrium’, with an effective mechanism of rent sharing.

Based on the analysis of the data collected during fieldwork, it is evident that the poor, illiterate, and marginalised suffer the most because of a lack of rule of law, and institutional inefficiency. In fact, they suffer twice. First, they suffer because they are the victims of land dispossession, and later they suffer again in the courts during the litigation process. The judiciary as an institution can have a profound impact on the overall well-being of the citizens of a country. As the fundamental institution to protect the principles of fundamental rights and justice, the judiciary can play a critical role in ensuring the rule of law. Nevertheless, in Bangladesh, if institutional inefficiency continues to persist in the judiciary, it can further propel poverty and marginalisation. Thus, the long-term sustainable development of Bangladesh critically depends on a well-functioning judiciary. For this reason, it is imperative to overcome institutional inefficiencies in the judiciary and to promote the rule of law.

Ultimately, overcoming institutional inefficiency in the judiciary of Bangladesh will require a lot more than the usual generic reform agendas. While there is a need for capacity building within the judiciary, a thorough review of and proper amendments to the existing laws in order to update century-long practices, and the establishment of low-cost legal services for the poor and underprivileged, these measures alone will not be enough to meet the challenges and issues in contemporary Bangladesh. The Government must take steps to ensure the separation of powers between the executive and judicial branches, in order to uphold judicial independence. At the same time, it should be kept in mind that ensuring judicial independence alone also may not be a sufficient measure for ensuring the rule of law if institutional inefficiencies persist in other areas in Bangladesh. Thus, with respect to judicial functioning regarding involuntary land dispossession, external interventions are required to break the inefficiency of the existing system. As long as the ‘equilibrium’ continues to exist, judicial reform alone will not be sufficient. In the past, there have been some failed attempts to digitise the land and court records. Even if the digitisation of court and land records will not necessarily result in the absolute removal of all forms of institutional inefficiencies in the judiciary of Bangladesh, it will surely contribute to improving its performance.

Annex 9.1 Glossary of Terms

| AC Land | Assistant Commissioner (Land) |

| ADR | Alternative Dispute Resolution |

| Balam Bohi | Book of land registration records |

| Bangladesh Survey | The Bangladesh Survey started in 1970 and is still ongoing |

| Bighas | Unit of land measurement (0.333 acres) |

| CS or Kistwar | The Cadastral Survey of undivided Bengal was the first comprehensive record of land rights in Bangladesh. It is still accepted by contemporary courts. The CS Record of Rights (RoR) was prepared under the Bengal Tenancy Act 1885. This is known as the CS. The survey started from Ramu of Cox’s Bazar upazila in 1888 and ended in 1940 |

| Char | Alluvial land or land thrown up from rivers |

| Daag | Plot number |

| DC | Deputy Commissioner |

| Kanungo | Union Land Assistant Officer |

| Khas land | Public property or government-owned land, where nobody has property rights. |

| Khatian | Cadastre or RoR containing the area and character of land (by plot or by owner) |

| Mastaan | Local goons |

| Muhuri | Assistant to a lawyer |

| Namzari | Mutation or actions of Tehsildars and Assistance Commissioners (ACs) (Land) to update records to reflect a change in ownership and physical alterations |

| Nazir | The chief of staff of the Nezarat |

| Nezarat | A central administrative office of a court dealing with a service of summons, etc. |

| Nirbahi | Executive |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| Peshkar | Bench clerk/bench assistant of a court |

| Revisional Survey | The Revisional Survey took place 50 years after the CS survey |

| RoR | Record of Rights (Khatian) |

| Settlement Attestation Survey or Pakistan Survey | The Settlement Attestation or Pakistan Survey of 1956–1962 |

| Shalish | Local informal adjudication |

| Sherestadar | An administrative officer assigned to each judge who sits in a separate room called the Sheresta and can receive a plaint/suit on behalf of the court |

| Tehsil | Lowest union-level revenue unit comprising several Mouza |

| Tehsildar | Local revenue collector |

| TNO | Thana Nirbahi Officer |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| WEF | World Economic Forum |

| WJP | World Justice Project |

Annex 9.2 Selected Case Studies

Case Study 1: Mr X lives in Raipur, Anwara. He is 76 years old. During the Pakistan Survey, part of his ancestral land, a pond, was mistakenly recorded as khas land or government property. Mr X filed a case to reclaim his possession; the case lasted for almost three years. Finally, in 1993, the verdict was in his favour. Mr X then went to the land office and applied for mutation. However, the upazila office refused to act on the verdict. Although Mr X showed them the verdict and requested them to solve the matter, they sanctioned the lease of the pond to another company. Mr X went to the DC and requested him to solve the matter. The DC ordered the TNO and AC Land to look into the matter. Even after that the problem was not solved and Mr X went to the High Court. Up to now he has been unable to obtain a hearing date. Mr X said that this has cost him around BDT 300,000, and he has to visit the court on a regular basis.

Case Study 2: Mr Y lives in Anwara. He is 47 years old. He used to live abroad as a migrant worker. A group of people claimed ownership over his homestead during the Bangladesh Survey. After learning of this, Mr Y filed a case at Patiya Court. However, according to him, the court did not check his documents thoroughly and dismissed the case. He then appealed to the District Court and received a verdict in his favour. The court gave an order regarding correcting the mistake in the Bangladesh Survey. After he completed the mutation, the opposite party in this case appealed against the verdict at the High Court. Nevertheless, once again, the verdict was in favour of Mr Y. Although Mr Y has the proper documents of ownership (land deeds, records from the Revisional Survey), the defendants are unwilling to accept the verdict. His case has been running since 2007 and until the time of the interview, Mr Y had spent around BDT 400,000 to pursue his cases. He said he managed these expenses by selling almost half of his property. The per day rate for a Supreme Court lawyer is BDT 100,000–150,000, which he feels is quite high. Mr Y believes that there is some kind of connection between both of the parties’ lawyers. Because of this informal contact, none of them wants to end the case soon: the peshkar, lawyer, and muhuri all have this informal connection, which is the main reason behind the long suit. The political power of the defendant’s lawyer is one of the major problems in his particular case.

Case Study 3: Mr Z lives in Banikpara, Anwara. He is 40 years old. His grandfather rented their ancestral land to a Muslim farmer for share cropping. When his grandfather became old, the farmer came to Mr Z’s father and told him that Mr Z’s grandfather owed him some amount of money. The farmer tried to force the family to sign a transfer of ownership of the land. Mr Z’s father then went to the District Court and filed a case. The court gave a verdict in favour of him. However, the plaintiff then went to the High Court and then to the Supreme Court and appealed against that verdict. As Mr Z’s father was very poor at that time, they could not go to the Supreme Court. As a result, the case went on for about 12 years. The current market price of the land is about BDT 600,000–700,000. Mr Z said that they have gone to the local chairman but nothing had happened. There were even incidents involving physical assault. Currently, the land is in the possession of the plaintiff party. Mr Z believes that they are suffering more because they are a religious minority in their community.

Case Study 4: Mr A is a farmer. He lives in Gazipur with his wife and four daughters. The problem started when his paternal cousin sold his land without his consent. The land includes his homestead, and its monetary value is about BDT 2,000,000. Mr A went to the shalish to solve the matter. However, according to him, the defendant influenced the shalish through a bribe. After being denied justice from the shalish, he was very disappointed and decided to file a case against his cousin. Nevertheless, before he could do so, he was threatened by his cousin’s husband, who is a dominant political leader in Gazipur. There were even instances of vandalism and although he was the victim, the local police arrested Mr A. He was in jail for about two months. After getting bail, he went to the court and filed a case. The case has been ongoing since then. There was a verdict five years ago which according to Mr A was distorted. As a result, he appealed against it. Mr. A said that from the very beginning, the opponent party influenced the case with money and power. From the local police to the court, he did not get justice anywhere. The defendant party did not only seize Mr A’s homestead: they are not even allowing him to utilise his other lands. He tried to build a house adjacent to the disputed land. After working for a few months, his brother-in-law used his political power again and demolished his hut. He is now living in a one-room house with five other members of his family. Mr A and his family have been suffering for a decade due to corruption, a lack of justice, and the effects of political influence.

Case Study 5: Mr B is the second among the six sons and two daughters of his father. He has one uncle who has a son and two daughters. They live in the village of Vanua in Gazipur Sadar. His father and uncle jointly bought 132 decimals (4 bigha) of land in 1978 from their neighbour, Mr E, who died in 2001. Mr E has five sons and a daughter. When the father and uncle of Mr B bought the land, they completed the registration and collected all the deeds associated with the land. After that they occupied the land and started to cultivate it. From that time onwards, the land has been under their possession and they provide the due taxes to the government associated with the land. However, in September 2016, the sons of Mr E filed a case in the court claiming that his father did not sell the land. From the case files, the family of Mr B came to know that before selling the land Mr E registered a portion of the land (13/14 decimals) in his son’s name. Thus, his sons filed a case claiming ownership of all of the 132 decimals of land and stated that the registration that Mr B’s family holds is not valid. Before filing the case, they did not inform Mr B’s family or any local representative. The family of Mr B had no choice but to hire a lawyer and the litigation is still ongoing. In August 2018, due to the request of Mr B’s family, the upazila AC Land investigated the land. When the AC Land came to investigate, the plaintiffs were absent because they thought that he was influenced by the defendants. Mr B thinks that the report of the AC Land will have a great influence in the verdict and hopes that the verdict will come in his favour as he has legal documents. The land associated with the case is agricultural land and the family of Mr B cultivate paddy in the land. Every year they get approximately BDT 240,000 revenue from the land. The cost of producing paddy is approximately BDT 130,000, which implies an approximate profit of BDT 110,000 per year. The current value of the land is approximately BDT 20,000,000 at the current market price. Moreover, as the land is situated in a good location (adjacent to the road), the value of the land is increasing day by day.

Case Study 6: Mr C lives in Bhanua, Gazipur. He is 47 years old and studied until Secondary School Certificate level. His father had four brothers and one step-brother and Mr C has three brothers and five sisters. There are five members in his household, including: his mother, his wife, and his two daughters. Mr C used to live in Saudi Arabia and worked as a day labourer. He came back to Bangladesh in 2010. When his father was young, his uncle convinced him to buy some land from him, around the year 1970. His father bought the land and obtained the deed; however, he did not know how to properly calculate the amount of land that he deserved. During that time, his uncle misinterpreted the total amount of land that he deserved and deprived him of the proper share of the land. However, during 1975, this same uncle demanded that Mr C’s father owed him some amount of land, and thus, the conflict between these two parties began. According to Mr C, when the two parties to the local shalish, they found out that Mr C’s uncle actually owed them around 2 bighas of land. Mr C filed a case in the District Court in 2012 and since then the case has been ongoing. Every time he visits the court, he has to pay the lawyer, peshkar, and muhuri. The fee of the lawyer is around BDT 2,000 and other costs vary from BDT 500 to BDT 1,000. The litigation process has cost him around BDT 80,000 till now. The present value of the land is about BDT 11,000,000. According to Mr C, frequent transfers of judges hinder the path to obtaining a fair verdict. Besides, an insufficient number of judges and excessive bureaucracy prolongs the litigation. He also believes that the local police and shalish are heavily influenced by a local political leader who is a patron of the defendant.

Case Study 7: Mr D lives in Vanua, Gazipur. He is 65 years old. He has two sons and a daughter. None of his children received a formal education. He went to Iraq in 1982 and worked there as a day labourer. His father was a farmer, and his grandfather had 24 acres of land. His father’s uncle claimed false ownership over his father’s property. When he came back from Iraq, he went to the shalish to solve the problem. The local chairman and member tried to solve the case. However, the opposing party did not accept the verdict and did not agree to give Mr D his land back. As a result, he went to the District Court and filed a case against them. After filing the case, the opposing party sent the police to threaten Mr D. For the past two years, he had to go to the court every now and then and most of the time the opposing party, who is a local political leader, is not present for the hearing. According to Mr D, money plays a vital role in the court process. The case has already cost him around BDT 200,000, over the last two years. From the lawyer to the muhuri, everyone demands money each time there is a date for a hearing.