“The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field. Go! I am sending you out like lambs among wolves. Do not take a purse or bag or sandals; and do not greet anyone on the road. When you enter a house, first say, ‘Peace to this house.’ If a man of peace is there, your peace will rest on him; if not, it will return to you. Stay in that house, eating and drinking whatever they give you, for the worker deserves his wages.”Footnote 1

Does religion affect legislators' support for organized labor? There has been an impressive growth in scholarship on religion's role in shaping elite-level political behavior, especially with regard to the personal religions of legislators (Fastnow et al. Reference Fastnow, Grant and Rudolph1999; Oldmixon Reference Oldmixon2005; D'Antonio et al. Reference D'Antonio, Tuch and Baker2013; McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013, Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2015; Guth Reference Guth2014; Mathew Reference Mathew2018). This literature fits into broader research on descriptive representation, in which elected officials represent the interests, values, and policy preferences of those communities with whom they share a background. Applications of the theory of descriptive representation include race (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999), ethnicity (Rouse Reference Rouse2013), gender identity (Swers Reference Swers2002), sexual orientation (Haider-Markel Reference Haider-Markel2007), and parental status (Burden Reference Burden2007), among others. Religious influence in Congress is apparent on cultural issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights, and general ideological orientations (Fastnow et al. Reference Fastnow, Grant and Rudolph1999; McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013, Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2015; Mathew Reference Mathew2018). While these relationships are now established, less is known about how religion connects with other salient policies.

This article considers religious influence on support for organized labor policy, a set of issues that are perennially at the center of American politics and are important to the doctrine of religious traditions. Dating back at least to the turn of the twentieth century, regulation of big business, labor, and related conflicts over taxation and social welfare spending have cleaved the American two-party system. Not only is this a stable feature of political conflict, but the parties have also maintained fairly consistent and opposing positions on the labor agenda, with Democrats generally more supportive, while Republicans are more sympathetic to business interests. This stability contrasts with issues of race and civil rights, which has seen a partisan realignment over time (Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989), and the newer cultural issues of the post-1960s landscape, which did not see a fully realized partisan realignment until the 1990s (Layman Reference Layman2001). Understanding the structure of this conflict is thus an important scholarly task.

Studying religious influence on support for organized labor is also warranted given the steady decline in labor unions' power since the middle of the twentieth century (Francia Reference Francia2006). The decline of organized labor is one of the culprits responsible for growing economic inequality (Western and Rosenfeld Reference Western and Rosenfeld2011), a shrunken welfare state (Roof Reference Roof2011), and reduced political power for lower-income Americans (Ahlquist and Levi Reference Ahlquist and Levi2013). As labor unions have declined, organized religion has also waned. To take one representative statistic, in 1974, only 7% of Americans were religiously unaffiliated; by 2014, that number had risen to 22% (Jones Reference Jones2016). Even with these respective ebbs in power, organized labor and organized religion are two of the most important social institutions in the United States. It is therefore surprising that there is a dearth of scholarship on connections between the two.

Using scorecards produced almost annually from 1980 through 2020 by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), we find that evangelical Protestant senators are significantly more opposed to the policy preferences of organized labor than any other religious group, but this relationship is inconsistent over time. Meanwhile, Jewish senators are the most pro-labor. Given the broader literature on the relationship between religious identity and congressional behavior, our findings suggest a number of important implications, including that evangelical Protestants anchor the conservative movement and Jewish senators anchor the liberal movement across a whole host of issues, including labor rights, and not just the culture wars. More broadly, the impact of religious identity on American politics is more pervasive than is often understood.

1. Religion, legislative behavior, and organized labor

Research on religious influence in Congress has mostly focused on cultural issues, tapping into the politics of sex, gender, and reproductive rights. This makes a great deal of sense, as most scholars recognized the importance of religion to American politics following the mobilization of the Christian Right into Republican politics during the 1970s and 1980s. The Christian Right devoted a lot of attention to challenging Roe v Wade, fighting the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, promoting prayer in public schools, and opposing the movement for LGBTQ rights (Wilcox and Robinson Reference Wilcox and Robinson2010). As the relationship between religion, cultural policy, and partisanship became more correlated over time (Layman Reference Layman2001), scholars increasingly examined legislatures to understand the nature of religious influence among elected officials. Researchers logically looked for religious influence where it was most likely to be found, which is among the same set of cultural issues that captured the attention of religious voters.

There are two fruitful ways we may summarize findings across this literature to develop expectations for religious influence on labor issues. One is to identify those policies where we consistently see the same political differences across religions. In other words, we ask, are there religious identities that routinely occupy one side of the debate regardless of the issue? The answer to this question will inform whether organized labor's agenda is likely to fit an established pattern. A second approach is to understand how the literature speaks to temporal change. In other words, we ask, what do we know about how the relationship between religion and representation has evolved over time? The answer to this question determines if we should expect religious influence to ebb and flow depending on the content of the agenda or shifts in partisan alignments. Since we leverage data across four decades, we are able to examine whether and when religion shapes support for organized labor.

A review of the literature offers greater insight into the first question than the second. Previous research indicates that evangelical Protestants are worthy of particular attention as likely opponents of organized labor. First, evangelical senators are the most ideologically conservative (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013; Mathew Reference Mathew2018). Moreover, evangelical Republicans have greater party unity, though effects are stronger in the House than in the Senate (Mathew Reference Mathew2018). The punchline of this research is that evangelical Protestants are likely to anchor the right side of the ideological spectrum, especially given their large numbers within the Republican caucus, because those votes of greatest salience to labor unions clearly speak to general ideological and partisan divisions. They also speak to the institutional relationship between organized labor and the Democratic Party, which ought to tap into partisan loyalties independent of ideology. This is important because labor unions promote Democratic party loyalty (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2021) while evangelical congregations promote Republican party loyalty (Layman Reference Layman2001). As labor unions have declined and evangelical incorporation into the Republican coalition has increased over time, white voters in particular have abandoned the Democratic Party. The absence of cues from labor unions to consider class interests politically salient corresponds to the rise of a politicized conservative evangelical movement cueing religious interests as most politically salient. This likewise corresponds to geography, with the highest populations of evangelical Protestants residing in states with low union membership. Per the theory of descriptive representation, this combination of forces likely influences evangelical elites as well as evangelical rank-and-file. Moreover, politicians are obviously aware that labor unions tend to promote a range of policies aligned with the Democratic Party and often endorse and support Democratic candidates with campaign resources (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2021).

Looking beyond measures of ideology and party unity, we see some issues where evangelicals appear unique in their conservatism, and others where they do not. Evangelicals tend to be distinctly conservative on cultural issues, such as abortion (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013, Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2015) and measures of cultural ideology (Edwards Smith et al. Reference Edwards Smith, Olson and Fine2010; McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013), though Catholics may be just as conservative, at least within the Republican Party (Fastnow et al. Reference Fastnow, Grant and Rudolph1999; D'Antonio et al. Reference D'Antonio, Tuch and Baker2013). On the other hand, evangelicals are not unique in their support for Israel, where they are joined by Jewish senators (Rosenson et al. Reference Rosenson, Oldmixon and Wald2009), on their votes for Charitable Choice and the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act, where they look similar to Catholics and mainline Protestants (Burden Reference Burden2007), or in their opposition to environmentalist groups, where they are aligned with colleagues from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Guth, Cole, Doran and Larson2016). Evangelicals are also unexceptional in their levels of support for nutrition assistance programs (Oldmixon and Schechter Reference Oldmixon and Schechter2011) and in measures of concern for animal welfare (Oldmixon Reference Oldmixon2017). In sum, this is a mixed portrait, with only some cause for expecting evangelical senators to be particularly opposed to the AFL-CIO.

Then there is the question of change over time. The literature on religion in Congress is mostly based on shorter time frames, such as a few congressional sessions. Among the exceptions to showcase longer time-series (Fastnow et al. Reference Fastnow, Grant and Rudolph1999; D'Antonio et al. Reference D'Antonio, Tuch and Baker2013; McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013; Mathew Reference Mathew2018), non-cultural issues are typically measured using DW-NOMINATE or ADA scores. If labor's agenda fits the patterns uncovered in those studies, then evangelical Protestants will probably look more conservative than their peers in later years. This is because as evangelicals were increasingly elected as Republicans, they became good team players and adopted the conservative politics of their new party, even on non-cultural policies. One recent study of the electorate shows a growing gap from 1988 through 2014 between white evangelical Protestants and the general public on whether the government or individuals are responsible for securing a standard of living (Deckman et al. Reference Deckman, Cox, Jones and Cooper2017). The magnitude of greater evangelical conservatism on this measure increased considerably in the wake of the 2008 economic recession and the emergence of the Tea Party. This timing is instructive given what political scientists know about how voters receive cues from elites in forming their opinions (Zaller Reference Zaller1992), and how secular realignments are often evident first among elites and only at a lag among voters (Key Reference Key1959; Carmines and Stimson Reference Carmines and Stimson1989; Adams Reference Adams1997). On the other hand, McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz (Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013) show that religious effects diminish over time as partisan effects become stronger. This means we might find null results across the board. In earlier years, evangelicals might not be economically conservative enough to stand apart from their fellow senators, while in later years, there might be little leftover variation once we account for party.

In the following analysis, we frame each religion in the U.S. Senate in comparison to evangelical Protestant senators. Despite the mixed evidence reviewed above, we suspect that evangelical Protestant senators are the most conservative regarding the agenda of organized labor. For one, there is a theological rationale for connecting Protestant religious teaching to economic conservatism. This notion dates to Max Weber's theory that Calvinist Protestant theological individualism contributed to the growth of economic individualism in the societies of the capitalist West (Barker and Carman Reference Barker and Carman2000). As Gorski and Perry (Reference Gorski and Perry2022, 40) describe it, “To follow Jesus and love America is to love individualism and libertarian freedom, expressed in allegiance to capitalism and unequivocal rejection of socialism.” The same emphasis on an individual relationship with God undergirding evangelical theology translates to individual responsibility to take care of oneself economically, and to oppose higher taxes, greater social spending, and a more active role for government (Emerson and Smith Reference Emerson and Smith2000). For example, in an analysis of a 2014 Pew Research Center report, Wald and Calhoun-Brown (Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2018) find that evangelical Protestants in the general public are second only to Latter-day Saints in their opposition to a larger government that provides more services, perhaps because both religious traditions view the church as the proper provider of community services, not the government. As descriptive representatives of these same communities, we expect evangelical senators to substantively represent those values. Second, many of the social welfare policies for which organized labor advocates are racially coded, particularly as it relates to attitudes toward African Americans (Gilens Reference Gilens1996). The longstanding and fraught racial history of white evangelical churches dates back to slavery, not to mention more recent exclusionary practices (Balmer Reference Balmer2010; Jones Reference Jones2020; Butler Reference Butler2021). It is thus difficult to easily disentangle religious and racial motivations from orientations toward the agenda of organized labor. Of course, we must also look beyond those factors prompting opposition to organized labor among evangelical Protestant senators, as there are theological, ideological, partisan, and historic dynamics within each of the other religious groups that inform our hypotheses.

1.1 Mainline protestant

Mainline Protestants, who represent a plurality of senators during our time-series, share the individualistic theology of evangelical Protestants according to the Max Weber theory connecting Protestantism and capitalism. Indeed, mainline Protestant political conservatism has generally been more focused on economic rather than cultural conservatism (Manza and Brooks Reference Manza and Brooks1997). As Wald and Calhoun-Brown (Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2018, 243) note, mainline Protestants, “enlisted their political predominance, due largely to their high socioeconomic status, to resist socioeconomic programs of social welfare and economic regulation.” If Weber's notion of a “Protestant work ethic” applies to issues of concern to labor, then mainline Protestant senators should match the social welfare conservatism of evangelicals.

However, there is also good reason to suspect that mainline Protestants are more supportive of labor compared to evangelicals, given the greater representation of the “social gospel” in mainline churches. Mainline Protestant clergy are more likely to preach that Christians must love their neighbors by working for social reforms, including care for the poor, support for labor actions, rent strikes, civil rights, and anti-war activism (Wald and Calhoun-Brown Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2018, 243–44). This is a different emphasis from the evangelical focus on personal salvation as the key to being a good Christian. While evangelical theology prioritizes individualism, mainline communities are more receptive to structural explanations of social ills and institutional efforts to address those ills (Smidt Reference Smidt2013). The greater concern for the economically and socially marginalized in society is thus likely to translate into relatively greater support for organized labor among mainline Protestant senators.

H1: Mainline Protestant senators will be more supportive of organized labor than evangelical Protestant senators.

1.2 Roman Catholic

For Catholics, we expect more support for organized labor given that the consistent ethos of individualism that is present in Protestant theology is not a feature of Catholicism. Moreover, the Catholic Church has a long history of support for organized labor, leading one scholar to characterize it as, “the world's most eloquent and consistent voice for the rights of all workers” (Gregory Reference Gregory1998, 912). A prominent example is Catholic leaders backing César Chávez and the United Farmworkers in their struggle for economic justice in California in the 1960s and 1970s (Prouty Reference Prouty2006). Another example is the 1986 pastoral letter issued by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, in response to Reagan era cuts to the social safety net, denouncing economic inequality and calling on the political system to increase the minimum wage, among other regulations on unfettered capitalism (Wald and Calhoun-Brown Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2018).

Writing about the expansion of the Christian Right from cultural to economic conservative activism, Wilcox and Robinson (Reference Wilcox and Robinson2010, 173) note that Catholics' “communitarian ethic does not mesh well with calls to cut back on programs that provide food and health care for the poor” and that some Catholic thought leaders fear an increase in abortion would result from a reduction in social welfare spending. This tension between cultural conservatism and economic liberalism cross-pressures Catholics more than Protestants, leading to a sorting by party in which Catholic Democrats act upon their faith through economic liberalism and Catholic Republicans adhere to church teaching through social conservatism. As D'Antonio et al. (Reference D'Antonio, Tuch and Baker2013, 59) put it, referring to Catholic members of Congress and their adherence to the positions advocated by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, “When it comes to key issues such as taxes, minimum wages, health care, defense spending, and the like, Catholic Democrats provide strong support for positions taken by the bishops whereas Catholic Republicans do not.” Consistent with this characterization, Mathew (Reference Mathew2018) finds that Catholic Republicans are just as conservative as evangelical Protestants in models regressed on DW-NOMINATE scores. On the other hand, McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz (Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013) show that evangelical Protestants are more ideologically conservative.Footnote 2

It is possible that because Catholics were key players in the twentieth century Democratic Party coalition that included overlapping identification as Catholic, immigrant, union member, and city dweller, a historic context far less prevalent in Protestant communities, that Catholics will not stand out as more pro-labor than their partisan peers. This is because their pro-labor proclivities led them to identify with the Democratic Party in the first place. If this is the case, Catholics should not be more pro-labor than others within their party because the effect of Catholicism on labor support would be mediated by party. However, we propose that given the historical relationship with labor and the fact that Catholic religious leaders take pro-union positions, that we will find intraparty differences between Catholics and evangelical Protestants.

H2: Roman Catholic senators will be more supportive of organized labor than evangelical Protestant senators.

1.3 Jewish

American Jews have been a mainstay of left-wing politics and the Democratic coalition at least since the New Deal (Levey Reference Levey1996; Wald Reference Wald2015). It is possible that the Jewish presence in the Democratic Party during this time resulted from a perception that a Democratic coalition organized around a liberal social economic agenda would protect Jews from persecution (Ginsberg Reference Ginsberg1993). Likewise, the experience of being a small minority in a majority-Christian country causes Jews to view their own interests as tied to the political stability that is afforded by welfare state economics (Cohen and Liebman Reference Cohen and Liebman1996). Jewish support for the labor movement might therefore result from a sense that Jewish self-interest is inextricably linked to nurturing a classically liberal system that allows Jews to participate fully as citizens (Wald Reference Wald2015). Weisberg (Reference Weisberg2019) finds that American Jews are distinctive in their economic liberalism when it comes to favoring government services, spending, and the guarantee of jobs and income, which complements the issues prioritized by the AFL-CIO and the labor movement more generally.

More directly, Jewish connections to the labor movement run deep both in the United States and internationally. Particularly, Jewish women played an important role in the labor rights movement of the early twentieth century, which likely has had a lasting impact on the way Jewish families view labor organizing in the United States. During this time, Jewish women were highly likely to work outside the home before they were married and to be a primary contributor to the family finances and the ability of their brothers to invest in their education. Some scholars suggest this may have increased their likelihood of becoming involved in labor union organizing compared to other young female immigrants in the same trades (Hyman Reference Hyman and Baskin1991). Moreover, experience in Europe and Russia, where revolutions imbued “whole generations of young [Jewish] women with the desire to fight for social justice” were brought with these immigrants when they came to America and passed on to the next generation (Weinberg Reference Weinberg1988).

During the turn of the twentieth century, Jewish men and women were fervent union activists (Weinberg Reference Weinberg1988). In New York, as in other major urban centers that had large Jewish populations Jewish “garment workers constituted the majority of unionized women workers and the majority of the membership of the Women's Trade Union League” and Jewish men and women emerged as union leaders, where they remained active in union leadership well past this era (Hardman Reference Hardman1962). Moreover, religiously, “the dignity of labor and concern for the rights of laborers” is emphasized in the Talmud and worker rights to strike and organize have been upheld by rabbinical writings (Yaron Reference Yaron2008). Of course, as we note with Catholic senators, Jewish history with the Democratic Party, particularly following the New Deal, could indicate that we will not find that Jewish senators are more pro-labor than other religious groups above and beyond party. However, given intra as well as interparty differences, the history of Jews in the United States, their minority status, their role in the labor movement, and the way scripture has been interpreted in the Jewish tradition will likely cause Jewish senators to be the most supportive of labor rights of all groups, especially evangelicals.

H3: Jewish senators will be more supportive of organized labor than evangelical Protestant senators.

1.4 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Senators from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) are typically among the most Republican and conservative members of Congress. While LDS politics is often associated with conservatism on cultural issues, such as abortion and LGBTQ rights, institutional dynamics make LDS adherents an odd fit with the labor agenda. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is an example of a “strict church” (Iannaccone Reference Iannaccone1992), meaning that congregants must adhere to a multitude of restrictions on their personal behavior, including the requirement to tithe 10% of their income to the church. UT, the state with the largest concentration of LDS adherents, was among the first outside the South to enact Right-To-Work legislation in the 1950s, and very few LDS have served in leadership roles within organized labor (Reference WoodworthWoodworth 2008/2009). In 1965, LDS church leaders even sent a letter to the 11 LDS members then serving in Congress discouraging their support for an effort to repeal the Taft-Hartley Act (Mangum Reference Mangum1968). This speaks to the more general point that there simply is not a significant history of LDS participation in organized labor as is the case in the Catholic and Jewish communities.

Given the role of charity and the sharing of resources within the LDS community, a centralized social welfare state from the federal government receives less support. Moreover, the oppression faced by early church leaders in the nineteenth century has infused the LDS community with a historic distaste for an active government role in society. While these factors point to an expectation that LDS senators will match the conservatism of their evangelical Protestant colleagues, it is also the case that there are simply not a very large number of LDS senators serving during the years under analysis, including former Senate Democratic leader, Harry Reid (D-NV). For this reason, it is possible that we may be unable to statistically test our hypothesis, or know if the results are driven by the small sample size or the true effect. Still, we think there are more reasons to expect LDS opposition to the agenda of organized labor to more closely resemble evangelical Protestants than other religions.

H4: LDS senators will not statistically differ from evangelical Protestant senators in their support for organized labor.

1.5 Other religions

Due to the hodgepodge of different, smaller religious communities that comprise other senators' religions, it is difficult to develop clear positive expectations for the relationship between “other” religions and support for organized labor. However, we do know from previous research that members of smaller religious minorities tend to occupy the left wing of the ideological spectrum on various issues (Burden Reference Burden2007). The lack of coherent unifying theology among this group of senators means that they are unlikely to match the conservatism of their evangelical Protestant colleagues. For this reason alone, we feel confident in expecting their relative liberalism when it comes to the labor agenda.

H5: Senators from other religious backgrounds will be more supportive of organized labor than evangelical Protestant senators.

We note that our tests of religious effects may underestimate the extent of the relationships because we are using the blunt measure of affiliation rather than accounting for religious behaviors or beliefs. Both Guth (Reference Guth2014) and Arnon (Reference Arnon2018) show that measures of religiosity among members of Congress reveal additional effects on substantive representation beyond religious affiliation. This lack of measurement precision means we are more likely to have type-2 errors than type-1 errors. We are limited by an inability to measure religiosity going back decades; of course, having many years of data means we have the advantage of being able to characterize change over time. Where we might lose some measurement precision in our main independent variables, we gain significant payoff in analyzing four decades of roll-call votes.

1.6 The sorting of the parties

Finally, since the 1960s, religious, racial, and ideological groups have sorted into distinct parties (Mason Reference Mason2018). This group sorting coupled with revision in the way the parties in Congress are managed and the strength of the parties in Congress (Lee Reference Lee2015) has led to unprecedented levels of polarization in the U.S. Senate. Congressional leaders have made the “Hastert Rule” that party leadership will not bring any bill up for a vote that will divide the party, a defining feature of both houses of Congress. This approach to governance means that as the partisan leadership in Congress has strengthened and the consequences of breaking with one's party has grown more severe, the ability to measure any intraparty differences may be washed away. The unprecedented level of party polarization in Congress also means that interest groups that once cut across the parties based on the issue at hand have become synonymous with one party (Macdonald Reference Macdonald2021). Labor is a good example of this “sorting” of interest groups. The rise of negative partisanship—the phenomenon whereby Americans largely align against the other party instead of positively affiliating with their own (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2018), means that those with the strongest negative partisanship will not just view the other party negatively, but will also define themselves as opposed to all groups associated with the out party (Mason Reference Mason2018). Given this electoral pressure on senators, we may not find direct effects of religion on voting on labor issues in the most recent years.

2. Data and methodology

The dependent variable in this analysis is the scorecard rating assigned to each U.S. senator by the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) in each year from 1980 through 2020, with the exception of a small number of missing years of data.Footnote 3 As the largest federation of unions in the United States, the AFL-CIO's agenda represents a valid measure of the policy goals of organized labor more generally. Interest group scores are widely used in the study of legislative behavior, both in the broader literature and in the sub-field of religious influence in Congress. For example, scholars have assessed religious influence in Congress using interests group scorecards from the Family Research Council (Edwards Smith et al. Reference Edwards Smith, Olson and Fine2010), the League of Conservation Voters (Newman et al. Reference Newman, Guth, Cole, Doran and Larson2016), and the Humane Society Legislative Fund (Oldmixon Reference Oldmixon2017).Footnote 4

AFL-CIO scores capture a couple of important dimensions of legislative behavior, particularly as it relates to religious influence. For one, varying levels of support for the AFL-CIO position on a vote tells us something about theological differences across religions with regard to individualism versus collectivism. Second, the AFL-CIO's advocacy for a more generous social welfare state and greater government intervention on behalf of laborers means the support scores capture ideological content, which we theorize as downstream of theological belief.Footnote 5 The vast majority of key votes are about wages, government spending, taxes, welfare benefits, trade, and related issues having to do with the government's role in the distribution of resources.

Over time, AFL-CIO key votes speak to perennial concerns having to do with unemployment benefits, retirement benefits, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), funding for the Department of Labor, regulations surrounding overtime pay, the minimum wage, trade agreements, federal workers' rights, opposition to cuts to social welfare programs and regressive tax cuts, opposition to mandated balanced federal budgets, support for jobs dedicated to ensuring energy independence, funding for transportation infrastructure projects, health care, prescription drugs, child care, family and medical leave, and pay equity for women. Votes on these and related issues represent the vast majority of key votes from 1980 to 2020. In addition, there are a smaller number of votes on nominations to executive branch positions and the courts, though these votes became much more prevalent in later years. From 1980 through 2012, only 14 out of 343 key votes concerned an executive or judicial branch confirmation. From 2013 through 2020, this ratio ballooned to 42 out of 97 key votes. For this reason, we expect to see a stronger effect for party in later years as fights over confirmations became a particular focal point of partisan warfare and as partisanship increasingly overwhelms religious effects (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013) and ideological or policy-based conflict (Lee Reference Lee2009). Other votes reveal labor unions' sometimes-uneasy relationship with other players in the Democratic coalition, including support for stemming the flow of undocumented immigrants and disagreement with environmental activists where job creation might clash with environmental protection. There is some variation in the number of key votes represented in each decade, with over 120 votes in each of the 1980s, 2000s, and 2010s, but only 65 in the 1990s.

In the results that follow, we present both descriptive statistics and time-series cross-sectional models using the score for each senator in each year of the study. The main independent variable of interest was gathered by identifying each senator's religious affiliation according to the procedure we used in previous research (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013). We conducted archival research of senators' biographies to determine their affiliation with specific churches, then aggregated those affiliations to the broad denominational families of evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, Roman Catholic, Jewish, and LDS. For religions with very small numbers of senators, such as those white Christians who do not neatly fit as evangelical or mainline, Black Protestants, Eastern and Greek Orthodox, Buddhists, and those without an affiliation, we created a code of “other religion” to avoid generalizing about large religious groups with very small samples in the Senate.

We also control for a number of individual and state-level control variables to account for potential spurious relationships. At the individual level, we model party identification, gender identity, race, and seniority. Since legislative behavior could be due to constituency effects, at the state level, we control for the percentage of each state's population that is evangelical Protestant, mainline Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, and LDS.Footnote 6 We also include the percentage of each state's population that is Black, college educated, belonging to a labor union, and a measure of state liberalism.Footnote 7 A final control for the South addresses regional effects, as both independent variables and the dependent variable likely vary geographically.Footnote 8

The unit of analysis in the time-series cross-sectional models is each senator in each year, such that we have 35 years of data and typically 100 senators in each year, depending on vacancies and senators who missed all relevant votes, leaving us with a sample size of 3,494 in the full model. The modeling strategy and the state-level control variables help us isolate the correlation of religious identity with legislative voting behavior above and beyond the influence of constituency, geography, and partisanship. The raw scores of the AFL-CIO scorecard range from 0 to 100, with 100 representing perfect voting records in support of the AFL-CIO's key votes. However, not all years perfectly ranged from 0 to 100. In some years no senators scored a 0, and in others, none scored a 100. As a result, we converted the raw score to a scale ranging from 0 to 1, along with every independent variable, to facilitate comparable coefficient sizes. A one-unit increase in each independent variable represents the expected change of a minimum to a maximum observed value and is equivalent to a percentage point increase in the dependent variable.Footnote 9

3. Results

We first present mean interest group ratings for senators in each religious group for the whole time series and for each year to test whether there is variation across labor support. In addition to comparing across religions, we evaluate whether there are differences in support for organized labor within each party's caucus. Next, we proceed to model the effect of religion on support for the AFL-CIO, including overall results inclusive of all years, and broken down roughly by decade.

The first column of Table 1 shows the mean AFL-CIO score by party and religion. Expected partisan gaps are apparent in the mean rating of 19 for Republicans versus 86 for Democrats. We see some initial evidence of religious differences, with evangelical Protestants (mean = 29) and those from the LDS faith (mean = 33) registering scores well below their peers. The next-most conservative religious group is mainline Protestants (mean = 50), while the most pro-union religious groups are Jewish senators (mean = 82), those from “other” religious faiths (mean = 70), and Catholics (mean = 63). As a very simple test of our hypotheses, we do find greater opposition to labor rights among evangelical Protestant and LDS senators.

Table 1. Mean AFL-CIO support scores by religion and party, 1980–2020

Note: Excludes 1983, 1986, 1995, 1998, 1999, and 2007.

To confirm whether the means in Table 1 are associated with constituency or individual factors we present Table 2.Footnote 10 The first column shows the effects of each religious group, relative to evangelical Protestants, on AFL-CIO support over the entire 1980–2020 time-series. The coefficients indicate that Jewish senators (+0.035), LDS senators (0.044), and senators from “other” religious backgrounds (+0.044) are significantly more supportive of labor than evangelical Protestant senators. For the remaining mainline Protestant and Catholic senators, there is no statistical difference with evangelical Protestants. This is noteworthy in that there is a clear division between senators of the larger Christian religions and those from smaller minority religions, with the latter groups representing more pro-labor legislative action. On the other hand, the hypothesized differences between evangelical senators and most of their fellow Christians are not apparent. The remainder of the first column reveals some other expected outcomes, including a strong result for partisanship (−0.582 for Republican affiliation), greater support for labor among women senators (+0.0540), and a potent relationship for state liberalism (+0.569).

Table 2. Cross-sectional time-series model of religion and support for organized labor in the U.S. Senate, 1980–2020

Driscoll–Kraay standard errors in parentheses. +p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Evangelical Protestants are the excluded comparison group in each model. All variables range from 0 to 1. Excludes 1983, 1986, 1995, 1998, 1999, and 2007.

The second and third models in Table 2 examine the 1980s and 1990s, respectively, to see if there is change over time. We do see some deviations in the results from these decades compared to the full time-series in the first column. Both mainline (+0.03) and Catholic (+0.03) senators are more supportive of labor than evangelical Protestant senators, as initially theorized, in the 1980s. Consistent with the first model, we also see positive and statistically significant effects for Jewish, LDS, and “other” senators. For votes cast in the 1980s, evangelical Protestant senators are uniquely opposed to the AFL-CIO's agenda relative to all other religions. These results shift in the 1990s, however, as the third column shows only Jewish (+0.04) senators registering a positive effect relative to evangelicals, while LDS (−0.02) senators have flipped to less support for organized labor compared to evangelical Protestants.Footnote 11

Finally, the last two columns include models broken down by each of the first two decades of the twenty-first century. During 2001–2010, the results once again mirror those of the 1980s, with each religion positively and significantly more supportive of labor than evangelical Protestants. For the 2011–2020 model, however, religion cannot compete with the overwhelming effect of party. Looking across the row of coefficients for Republican party affiliation, it is clear that the initially strong effect in the 1980s steadily grows to an eye-popping −0.720 by the 2010s. This is noteworthy given the range of the dependent variable from 0 to 1. As partisan polarization increased over time, religion decreased as a direct effect on support for organized labor due to partisan sorting. Instead, religion operates indirectly through party as each caucus has sorted by religion and party over time (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013; Mathew Reference Mathew2018). The lack of direct religious effects in the 2010s is also likely a product of the aforementioned changing AFL-CIO agenda from mostly labor and social welfare key votes to a much larger share of votes on executive and judicial branch confirmations from 2013 through 2020 that were almost entirely partisan. In fact, if we exclude the four years with the most key votes on confirmations (2013, 2017, 2019, and 2020), Catholic senators are significantly more supportive of labor than evangelical senators in the full 1980–2020 model (+0.02, p < 0.10), which is a result more consistent with initial expectations.Footnote 12

Still, the apparent effect of religion on support for organized labor as recently as the 2001–2010 decade is impressive given the growth in party polarization since 1980. While the effect of party swelled in the 2011–2020 model, it was also quite large in the 2000s (−0.62). The unique position of evangelical Protestant senators as a distinct source of opposition to organized labor in these later years of the time-series is particularly notable given this context of greater partisan polarization. Prior to the 2010s, the most consistent finding is that Jewish senators anchor the left and evangelicals anchor the right when it comes to issues of importance to organized labor. Other religions swing between those two poles depending on the decade, but tend to align more closely with Jewish senators in support of organized labor.

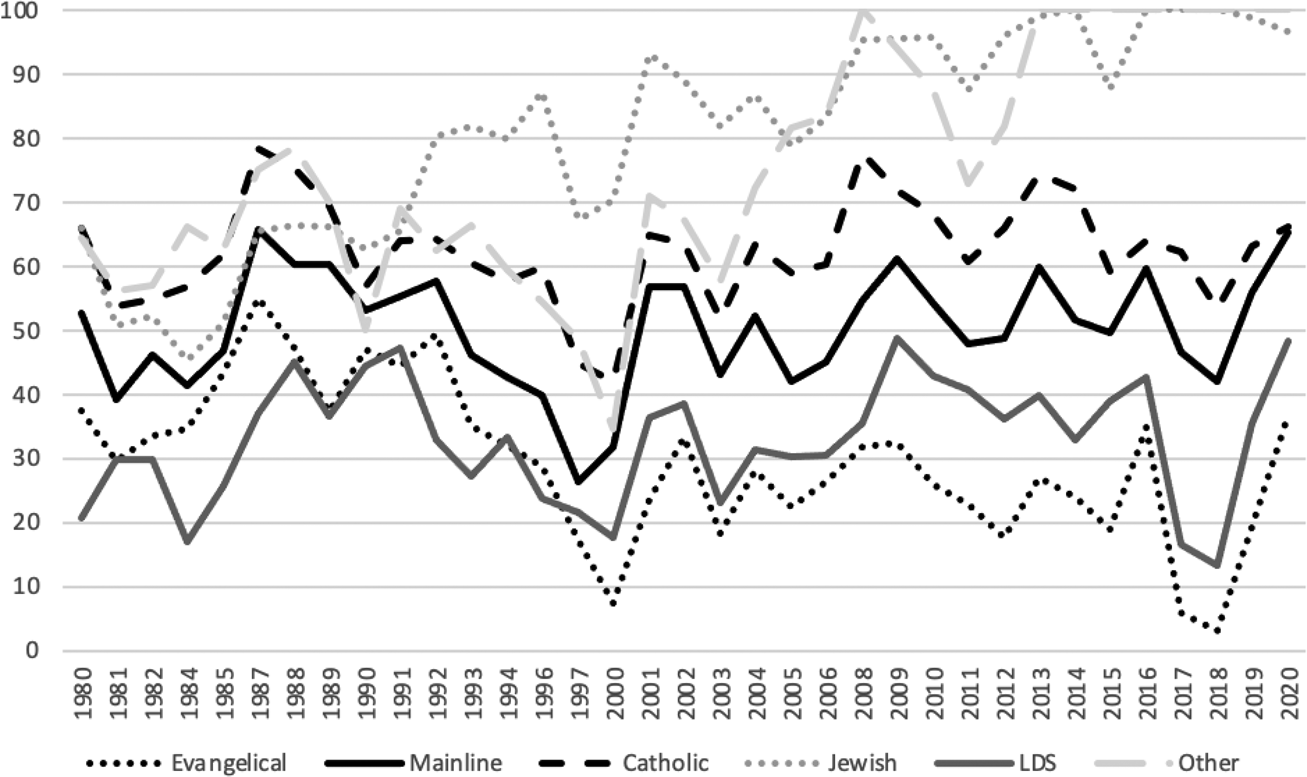

Another look at the data further speaks to change over time as revealed in Table 2. Figure 1 shows each religion in the U.S. Senate and their support for labor from 1980 through 2020. The more clustered collection of religious backgrounds earlier in the figure widens over time. However, this widening is not driven by senators from all religions. Instead, we see evangelicals becoming more ardent opponents of labor, paired with increasingly unified support for labor among Jewish senators and those of minority religions faiths. Mainline Protestant and Catholic senators vary between support scores of about 40 and 70 throughout the four decades, while Jewish, “other,” evangelical, and LDS senators migrate away from the center, especially after the early 1990s. In the 1980s and 1990s, Jewish senators' mean pro-labor score is 66, but that grows to 88 in the 2000s, and even reaches a perfect score of 100 in some of the 2010s. A similar dynamic plays out for senators of “other” religious backgrounds. While Jewish and “other religion” senators were growing more pro-labor, evangelical Protestant senators were heading in the other direction. In the 1980s and 1990s, evangelical senators had a mean score of 38, but that fell to 24 in the 2000s, even cratering to single digits in 2018.

Figure 1. Religion and support for organized labor in the U.S. Senate, 1980–2020. Excludes 1983, 1986, 1995, 1998, 1999, and 2007.

On the whole, our findings confirm expectations that evangelical Protestants would be the least supportive of organized labor and Jewish senators would be the most supportive. This is true in each model up to the final decade of the analysis, when party overwhelms the impact of most other variables. Likewise, senators from “other” religions tend to be significantly more supportive of labor than evangelicals, though this result does not quite achieve statistical significance in the 1990s. Mainline and Catholic senators are more supportive relative to evangelicals in two decades, the 1980s and 2000s, but not in the 1990s or 2010s. LDS senators are more supportive than evangelicals in two decades, the 1980s and 2000s, but less supportive during the 1990s.

4. Discussion

Religion is related to senators' legislative behavior above and beyond the typical cultural issues of abortion, birth control, LGBTQ rights, and women's rights. Our data of senators' behavior on the agenda of organized labor show that, consistent with their religious group's beliefs, evangelicals are the most consistently opposed to labor's agenda and Jews are the most consistently supportive, above and beyond other individual and constituency factors. To take one example, Jewish Sen. Arlen Specter, who served PA as a Republican from 1981 through 2009, had an average AFL-CIO support score of 61, which is triple the Republican mean of 19. Another example, controlling for party and state, contrasts Jewish Sen. Howard Metzenbaum of OH to mainline Protestant Sen. John Glenn of OH. Both OH Democrats whose terms overlapped for all but a few years, Metzenbaum's mean AFL-CIO score was 94 while Glenn's was 78. While both members of the Democratic Party from the same state, Metzenbaum was more supportive labor's agenda than Glenn. Our models from 1980 through 2020 indicate that party explains the overwhelming amount of variation in voting, but it does not explain everything. Religion adds to our understanding of the politics of organized labor.

While we argue that religion is related to orientations toward labor, there is such a high level of polarization in the most recent years that direct religious effects are easier to find among senators at the point of choosing a party (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013; Mathew Reference Mathew2018). Though players such as Arlen Specter used to be able to serve as a Republican but regularly break with the party on certain issues, that type of party heterogeneity is no longer tolerated. While party polarization and party unity currently reign supreme, someday the U.S. Congress may reach a breaking point in which another realignment upends the current coalitions, which would allow greater intra-party diversity in roll-call voting to emerge once again. If that day comes, we would expect religion to again exhibit direct effects on congressional voting on organized labor's agenda.

Evangelical Protestant senators are uniquely opposed to the policies that comprise the core agenda of organized labor and Jewish senators are uniquely supportive. Evangelical Protestants place a greater emphasis on the individual's personal relationship with God to ensure a privileged position in the afterlife. Evangelical theologians also do not preach the “social gospel”—that the Kingdom of God should be pursued by making life better on Earth (Wald and Calhoun-Brown Reference Wald and Calhoun-Brown2018). There is thus a clear religious underpinning for the lack of evangelical support for labor. With evangelical members of Congress playing a starring role in the growth of partisan polarization (Mathew Reference Mathew2018), and with polarization itself a key driver of economic inequality (McCarty et al. Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2016), this paper's focus on the issue agenda of organized labor has added another piece of the puzzle to understand how those two seemingly distinct phenomena are related. The emergence in recent decades of a new wave of evangelical political mobilization, coupled with the continued growth of economic inequality, has not just coincidentally paralleled each other. Likewise, as Jewish and other minority religious groups become a larger presence in the Democratic Party's congressional caucuses over time (McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz Reference McTague and Pearson-Merkowitz2013), we may see a reinvigorated labor identity within the party.

Part of the dynamic we uncover here is also likely due to negative partisanship and political competition in response to the sorting of groups in partisan politics. Interest groups have increasingly become associated with distinct political parties, and as a result, attract or repel potential allies due to their association with that party. Organized labor fits this dynamic as a Democratic Party-aligned group. Above and beyond partisan considerations, it is also consistent with theological differences emphasizing individualism or collectivism, which translates to religious groups being more or less amenable to the policy proposals of labor unions. These general orientations, connecting theology and ideology, are also embedded in different histories between adherents of different religious communities and labor unions. There is a history of Jewish and Catholic engagement in labor union organizing that is simply less prevalent in either evangelical or mainline Protestant traditions. This combination of theology and historical context represents a powerful political force in contemporary American politics. Scholars would be wise to continue paying close attention to how the inter-relationships between religion, party, ideology, and other potent institutional forces in American politics shape the most consequential social and political outcomes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048322000281.

Data

Data for replication purposes will be provided by the authors upon request.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

John McTague is associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Towson University. His research and teaching interests focus on American political parties, religion and legislative behavior, authoritarianism, race, and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Shanna Pearson-Merkowitz is a professor and associate dean of Faculty Affairs in the School of Public Policy at University of Maryland. Her research and teaching interests focus on religion and legislative behavior, public opinion, political polarization, racial and economic inequality, and state and local government.