1 Introduction

On March 28, 2017, just days before the grand ceremony honoring the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi 黃帝) in Xinzheng (新鄭) City, Henan (河南) Provin ce, I was invited by the Henan provincial government to attend an international forum on “Yellow Emperor Culture (黃帝文化).” During the accompanying banquet, I engaged in vibrant discussions with other attendees. A local official from Xiping (西平) County, Henan, shared ambitious plans to promote the legacy of Leizu (嫘祖), Huangdi’s legendary first wife, and detailed an upcoming worship event dedicated to her. A scholar from Hubei (湖北) Province offered insights into their research on Shun (舜), one of ancient China’s revered sage kings, while an official from Luyi (鹿邑) County emphasized the value of Laozi’s (老子) teachings in establishing Luyi as a hub for “Laozi culture (老子文化).” Four days later, I traveled to Xi’an (西安) to participate in the Tomb Sweeping Festival honoring Huangdi in Shaanxi (陝西) Province. There, I attended a conference on “Huangdi culture,” and met Mr. Huo, a senior scholar-official from Baoji (寶雞), Shaanxi. Mr. Huo ardently advocated for the legacy of Yandi (炎帝), the Flame Emperor, a legendary figure believed to have reigned alongside the Yellow Emperor. The prevailing narrative recounts the myth of Yandi’s defeat by the barbarian Chiyou (蚩尤) and his subsequent alliance with Huangdi to overcome Chiyou in Zhuolu (逐鹿), Hebei (河北) Province – a pivotal event in the foundation of Chinese civilization. Today, Zhuolu commemorates these figures with a joint ceremony at a cultural park featuring three temples dedicated to Huangdi, Yandi, and Chiyou. In Shaanxi, I encountered other local officials, each overseeing ceremonies for a “deity,” “ancestor,” or “historical celebrity.” After participating in two grand ceremonies honoring Huangdi within one week, I was struck by the feeling of stepping into a “garden of deities,” where mythical figures from Chinese history seemed vividly alive.

The Chinese people are often referred to as the descendants of Yandi and Huangdi – collectively known as “Yan huang zisun (炎黃子孫),” meaning “descendants of the Yan Emperor and the Huang Emperor.” The figures described earlier are central to China’s foundational origin myths and are key to the mytho-historical narrative of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors (三皇五帝), a period traditionally believed to span from 2900 BC to 2100 BC. The estimated time span may vary depending on the sources consulted. This era is often regarded as the early phase of Chinese civilization, predating the establishment of dynastic China. The concept of “Yan huang zisun” and a linear, cohesive narrative of Chinese history emerged during the nineteenth century, a period marked by the transition from imperial China to a modern nation-state (Shen, Reference Shen1997). Today, enthusiasm for common ancestors has experienced a resurgence, finding new expression within popular religion and the framework of cultural heritage, particularly under the influence of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). These mythological figures are now regarded as real ancestors to be honored by the government. The Chinese state has actively promoted ceremonies, festivals, and the construction of temples and monuments to commemorate these ancestors, officially recognizing them as part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.

In the context of global heritage-making, it is crucial to avoid overgeneralizing or standardizing practices such as heritagization (Walsh, Reference Walsh1992) or UNESCOization (Berliner, Reference Berliner2012) across the world. Instead, critical heritage scholars should examine how different cultures respond to these global heritage trends and engage with the processes of globalization (Herzfeld, Reference Herzfeld2004). This raises important questions: How is cultural heritage situated within China, and how is it translated, transformed, and embedded in its contemporary sociopolitical, cultural, academic, and local contexts? Specifically, this Element investigates the role of the cults of the Yellow Emperor and other mythic ancestors in promoting nationalism in China. It examines how UNESCO’s heritage discourse has been leveraged to support the revival of popular religion and traditional culture, even triggering new religious expressions. Furthermore, it explores how heritage discourse has been transformed and internalized in China, where localism and competition have emerged, leading to new forms of heritage rivalry. Focusing on the cult of the Yellow Emperor, this Element examines the rise of remote ancestor ceremonies in contemporary China, alongside the national enthusiasm for heritage listing and heritage-making, all set against the backdrop of China’s search for national roots, where heritage discourse plays a central role in shaping both cultural and political landscapes. Despite criticism of the tangible–intangible distinction by critical heritage scholars, the inclusion of intangible heritage discourse has profoundly reshaped China’s understanding of what constitutes heritage. This Element retains the term “intangible cultural heritage” (hereafter ICH).

This widespread revival of popular religion stands in significant contrast to Marxist atheist ideology. During Mao’s regime [1949–1976], practices such as ancestor worship and temple visits were condemned as relics of feudal superstition. With the political loosening after the economic reforms in 1978, religious activities gradually resumed once again. Since the 1990s, there has been a resurgence in locally organized religious events, festivals, ancestral rites, and the construction of temples in every place, despite the relatively passive stance of the central government (see also Chau, Reference Chau2006). However, in recent years, particularly since the 2000s, there has been a notable resurgence of these traditional customs, demonstrated through performances, folk dances, rituals, and religious practices, aimed at their promotion and preservation under the framework of ICH. In other words, aside from the general public, both governments and elites are becoming increasingly enthusiastic about promoting certain religious practices, albeit selectively, under official policies.

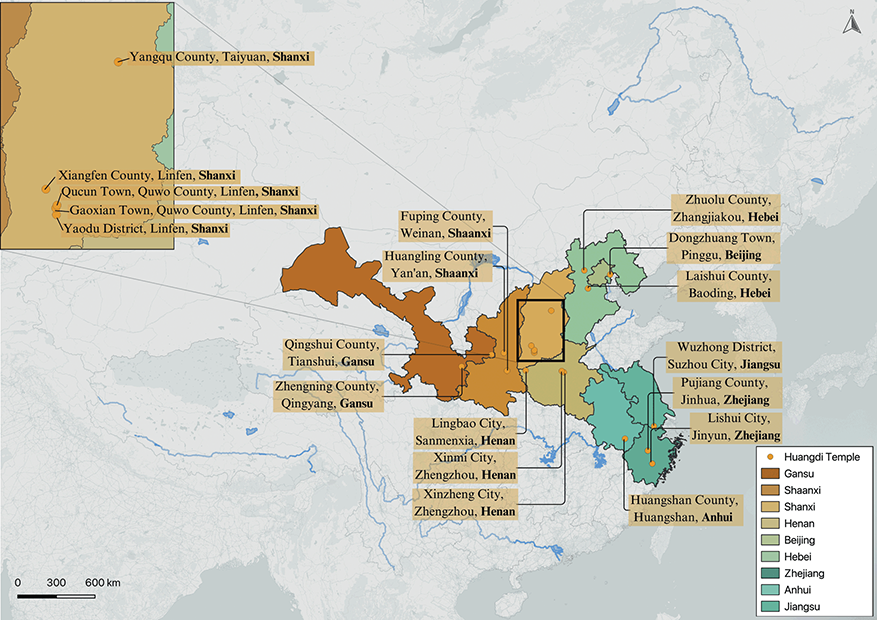

In today’s China, there has been a significant resurgence in popular religion, evident in its growing prevalence and vitality (Chau, Reference Chau, Ashiwa and Tank2009; Johnson, Reference Johnson2017; Madsen, Reference Madsen2014). Among the diverse religious practices experiencing a revival, one notable trend is the emergence of large-scale “remote ancestral cults,” a term I coined, which pay homage to legendary ancestors from distant epochs. These ceremonies actively involve various levels of governments, local officials, scholars, and numerous lineage organizations. Ancestor worship, once confined to familial or lineage settings, has now expanded into expansive communal rituals, increasingly managed by local governments in collaboration with tourism, commerce, and economic bureaus, drawing thousands of participants. Since the 1990s, my research has observed a gradual revitalization of Huangdi worship activities on a small scale in several places that are historically connected to Huangdi. Starting from 2000, government-led large-scale ceremonial events have been organized in Shaanxi, Henan, and Zhejiang (浙江), gaining recognition as national-level ICH. In addition to Huangdi, there has been a resurgence in the veneration of various “deified ancestors” such as Nüwa (女媧), Pangu (盤古), Fuxi (伏羲), Yandi, Dayu (大禹), Shun, Yao (堯), and other figures from the mythical period, across China. Although the temporal understanding of the concept of myth was introduced from Japan only in the late nineteenth century, debates surrounding these figures can be traced through various official historical and even “unorthodox” ancient texts throughout imperial China, due to their remoteness in time. In these contemporary new religious expressions, “mythical” and “legendary” figures from ancient Chinese culture are being rejuvenated through large-scale ancestor worship initiatives orchestrated by various local governments. Surprisingly, these large-scale ancestral cults are in the process of applying for various levels of heritage designation, signaling official recognition and endorsement of this practice of root worship and ancestral searching.

This zeal for rediscovering the national past and tradition, including religion – once dismissed as superstition or incompatible with modernity – is helping to foster a sense of national pride in China’s long history, resonating with Benedict Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1983) concept of the “imagined community.” Anderson (Reference Anderson1983) emphasizes the “imagined” nature of national communities, where shared media, language, symbols, narratives, and cultural practices foster a sense of belonging among people who may never meet. These elements, many drawn from a nation’s cultural heritage, contribute to the creation of a collective identity. Similarly, Michael Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1991, Reference Herzfeld1997) has explored the concept of the “historical imaginary,” in which certain historical events or figures are selectively remembered or forgotten to shape new narratives that suit present needs. In this view, history is not a static, fixed record but a dynamic and selective process through which societies reinterpret and reimagine their past to serve contemporary ideologies, power structures, or societal goals. Herzfeld’s approach often focuses on how national identities and cultural practices are shaped by these reimaginings and appropriations of history. In this context, Herzfeld’s work complements Benedict Anderson’s theory of “imagined communities,” where the shared narratives of the past (whether through print media, heritage, or collective memory) are instrumental in creating a sense of national cohesion. Additionally, Hobsbawm and Ranger (Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983) examine the constructive nature of tradition, arguing that nationalism is closely tied to state formation and often involves the “invention” of traditions to promote unity. They highlight that much of what is considered “traditional” or “heritage” is actually a modern construct, shaped by historical forces and political agendas, thus challenging the view that traditions are inherently ancient or natural. While all four scholars view nationalism as a modern phenomenon, closely tied to the development of capitalism, print media, and the modern state, this Element also adopts a constructive approach to China’s nation-building, highlighting the heritage boom with distinct Chinese characteristics that reflect the country’s unique cultural landscape.

Building on this discussion, this Element analyzes various remote ancestral cults within the framework of contemporary nation-building, the continually selective use and construction of history, the transformation of tradition into heritage, and the ways in which heritage discourse has empowered this process, shaping a new heritage landscape in China. First, this Element argues that the cults of the Yellow Emperor are driven by strong nationalism, aiming to unify China’s ethnicities and territorial integrity through a shared lineage based on blood and kinship. Recent leadership policies, such as the “China Dream,” reinforce this emphasis by linking national revival to cultural heritage. The UNESCO heritage discourse echoes this sentiment, promoting the idea that heritage strengthens national identity. Together, these forces reinforce the resurgence of the Yellow Emperor cult as a tool for cultural and national consolidation. Heritage projects, like those reviving popular religion or traditional culture, seek to construct a cohesive national narrative by linking people to a shared past. These initiatives are playing a vital role in cultivating an imagined community (Anderson, Reference Anderson1983) in modern China, enabling individuals from diverse regions and backgrounds to connect with a unified historical identity.

Second, this Element observes a grassroots revival involving localities and individuals motivated by a search for national glory and a return to traditional culture. Local religious revivals, which have been emerging since the 1980s reform era, play a crucial role as communities reconnect with historical and cultural roots. As Stewart (Reference Stewart2016, p. 300) asserts, “History thus takes shape in a hermeneutic circle consistent with Gadamer’s (Reference Gadamer1994) idea of ‘historically effected consciousness,’” wherein historical documents and heritage sites serve as repositories of social memory, integrated into individual cultural memory and actions.

Third, the Element identifies a new shift in China’s heritage discourse, where localities – municipal, county, or provincial – shape their identities by aligning with legendary or historical figures and organizing public ceremonies to honor these ancestors. Handler (Reference Handler, Brosius and Polit2011, p. 48) argues that “the contemporary world is organized by the model of the nation-state,” in which nations are imagined to possess cultural properties that define their identity and legitimacy. Echoing Handler, this ethnography reveals how localities in China, much like individuals, construct distinct personalities through cultural heritage. In the context of globalization, as Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1999) suggests, “culturalism” positions local culture as a marker of unique identity, making it essential to examine how this local cultural production materializes. The construction of local identities will be discussed in Sections 4 and 5 through case studies in Huangling 黃陵 (Shaanxi), Xinzheng, Xinmin 新密, Lingbao 靈寶 (Henan), and Jinyun 縉紜 (Zhejiang).

Additionally, this resurgence is empowering a group of academic nationalists – including historians, archaeologists, and heritage makers – who are celebrating various ancestors and reshaping historical narratives. This academic nationalism is strengthening the cultural significance of the Yellow Emperor and other ancestral figures, contributing to the larger project of redefining China’s past to suit contemporary national and cultural goals. My research on ancestral cult ceremonies found ongoing efforts by Chinese scholars to authenticate ancient texts and use archaeology to prove the historical existence of these figures, and this will be described in Section 5.

Drawing on ethnographic investigations conducted in China between 2017 and 2024, this Element examines the contemporary remembrances and appropriations of Huangdi as a common ancestor of the Chinese people, intertwined with an analysis of heritage-making processes in China. It transcends long-standing debates over Huangdi’s historical or legendary status, traditionally examined by historians (Shen, Reference Shen1997; Wang, Reference Wang2002), and discussions on the construction of “Chinese” racial identity (Dikotter, Reference Dikötter1992; Fei, Reference Fei1989).

Instead, this Element primarily focuses on understanding how and why the revival of remote ancestral cults is influenced by national identity, local placemaking, and the heritage discourse. The Element uncovers the mechanisms behind cultural revivals and historical consciousness, driven by diverse actors and influenced by various factors in contemporary times. Historians continue to debate Huangdi’s role as the ancestor of Chinese civilization, or even to question his existence, while archaeologists diligently seek material evidence that could provide insights into Huangdi’s historical presence. Both efforts are supported by the state, aiming to establish a cohesive, unified Chinese ethnicity. Local governments vie to assert their legitimacy by organizing annual ceremonies, erecting monuments, and constructing temples dedicated to ancestor worship under the banner of “Huangdi culture.” Beyond institutional efforts, this Element highlights how the desires of ordinary people for religious practices, ancestral veneration, and national unity contribute to the commemoration of this national ancestor. This is evident in the construction in his honor of temples, sculptures, and monuments that are gradually shaping new religious practices.

This revival reflects a nationwide resurgence of folk religious practices in public spaces following the Reform and Opening-Up era, and intriguingly promotes the phenomenon of Yellow Emperor Fever as ICH. While the pursuit of autochthonous common ancestors aims to build a kinship-based lineage among all Chinese people, including diverse ethnic minorities, there exists a dynamic tension between central and local authorities, as well as among localities in the scale and rights of holding Yellow Emperor ceremonies. I have observed a competitive spirit among localities, each striving to assert their “ownership” of these figures and the cultural heritage they embody. Driven largely by nationalism, this discourse on heritage aims to depict China as a historically profound nation. Yet, it also underscores a localized Chinese heritage discourse with regional competition, as localities strive to brand themselves with distinct cultural heritages, as argued in this Element.

2 Locating Religious Revivals in China within the Framework of Intangible Cultural Heritage

National Cultural Revivals

Living in today’s China, it is evident that history is prominently and grandly displayed, from public monuments and sculptures to historically themed shopping districts, theme parks, restored temples, and impressive museums (Anagnost, Reference Anagnost1997; McNeal, Reference McNeal2012). A strong historical sense of the ancient Chinese nation is conveyed both spatially and visually through various heritage projects. This phenomenon has been bolstered by the introduction of the global heritage discourse, particularly with the establishment of the World Heritage Sites designation in 1972. China signed the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in 1985, and since 1987 has actively pursued the nomination of various historical sites as World Heritage candidates. Furthermore, the adoption of the Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004 has further deepened China’s commitment to preserving its traditional culture and practices.

Since China began its extensive economic and social transformation following reforms in 1978, there has been a notable resurgence of interest in the country’s historical heritage. This interest reflects a desire to reconcile with past ideological shifts and the rapid societal changes brought about during the reform era. This appreciation of tradition and history marks a sharp contrast to Mao’s era, when iconoclasm sought to erase China’s historical legacy. The shift in China’s view of its heritage emerged not only in response to the global heritage discourse but also within a specific political and social context. Beginning in the 1980s, as the Communist Party transitioned from Marxist-Maoist ideology to a market economy, the move challenged its political legitimacy rooted in communism (Guo, Reference Guo2004). This “crisis of faith,” triggered by Deng Xiaoping’s Open-Door policy, sparked significant social upheaval. In response to these ideological changes, the Chinese government not only vigorously promoted national traditions to rejuvenate the nation’s culture and spirit but also made the appreciation of China’s historical past a central component of various political projects, even institutionalizing it. For example, Chinese state rhetoric has reinterpreted Confucianism in various political contexts. Political leaders such as Jiang Zemin publicly endorsed Confucian values, reasserting Chinese culture as Confucian and highlighting how patriotism and tradition harmonize with socialism (Guo, Reference Guo2004, pp. 30, 74). Xi Jinping has rhetorically embraced the “China Dream (中國夢),” positioning China’s rich traditions as sources of national pride and confidence. In 1994, a project was launched that framed heritage sites and museums as a basis for patriotism. The integration of historical narratives and traditional values into patriotic education underscores both China’s millennia-old cultural glory and its more recent challenges, shaping the official narrative of China’s global ascent (Callahan, Reference Callahan2005; Guo, Reference Guo2004). “Cultural heritage” has been strategically employed to foster nationalism and provide a moral foundation for the legitimacy of the Chinese state as it transitioned from Marxist ideology to a reform-oriented era aimed at achieving a “spiritual socialist civilization” and a “harmonious society” (Madsen, Reference Madsen2014). This renewed embrace of China’s historical past and traditional culture is being fueled by the nation’s economic development and a surge in national confidence. This national revival mirrors global trends in heritage appreciation, where relics, traditional cultures, and historical narratives are increasingly valued as national or World Heritage sites, strengthening local and national pride and identity. As a result, the Chinese heritage landscape has become distinctly shaped by political instruments.

Additionally, since the 1980s, there has been a rise in “academic nationalism,” with official sponsorship and extensive study of Chinese philosophies such as Confucianism and Daoism attracting more followers and enthusiasts (Guo, Reference Guo2004, p. 124). At the local level, many Chinese intellectuals have actively advocated for using traditional Chinese values to guide society, sparking widespread enthusiasm known as the “national essence fever” (國學熱) across the country. Recent scholarship has observed a new trend over the past decade: the emergence of neotraditionalism and new Confucianism. This is evident in the global expansion of Confucius institutes and the revival of interest in traditional attire (known as the Hanfu revival movement), driven by grassroots individuals and local actors, that traces its origins to Huangdi as the progenitor of Chinese civilization and promotes a distinct vision of traditional clothing (Carrico, Reference Carrico2017). The cults of the Yellow Emperor and various other deified ancestors have emerged within a nationwide zeal for China’s national past.

At the same time, indigenous popular religion, which has guided moral conduct in Chinese society for centuries, is undergoing a resurgence. This revival of popular religion has simultaneously fueled growth in religious tourism within China. As China opened up and underwent reforms, increased citizen mobility facilitated the rise of heritage tourism, exemplified by Han Chinese visiting destinations like Lijiang for ethnic tourism (Zhu, Reference Zhu2018). Oakes and Sutton (Reference Tim, Sutton, Oakes and Sutton2010, pp. 6–7) note how government-managed tourism guides citizens toward exemplary modern behavior.

Madsen (Reference Madsen2014), McNeal (Reference McNeal2015), and Oakes and Sutton (Reference Tim, Sutton, Oakes and Sutton2010) all emphasize the pivotal role of heritage in serving as a moral framework for regulating Chinese society. They note the resurgence of popular religion in China, reflected in the contemporary framing of heritage as a tool for patriotic education and cultural confidence. This includes the designation of temples, monuments, and cultural practices as heritage sites. This revival of China’s historical consciousness can be attributed to the country’s transition to a market economy, the rise of new Confucianism (which integrates Marxism with traditional culture to rejuvenate capitalism), and the promotion of a moral society with exemplary figures, all reflecting the state’s efforts to nurture national identity.

Across the discussed heritage sites, markers of patriotic education are prominently displayed, promoting nationalism through heritage preservation. Scholars studying cultural heritage in China have found that heritage legitimizes political governance and contributes to social cohesion and stability. However, these analyses often overlook the roles played by various non-state entities in the heritage-making process and fail to recognize how heritage discourse can reshape or even promote new historical narratives, thereby reformulating regional identities. This Element finds that the appropriation of heritage discourse is playing a significant role in shaping regional and local identities in China. It will explore this further through case studies of the cults of the Yellow Emperor in various localities in China.

Intangible Cultural Heritage in China

Since the 1980s, a significant influx of discourse on UNESCO’s World Heritage has permeated China, igniting a distinctive heritage fever phenomenon. Nearly every year, a new potential heritage site has been nominated for World Cultural Heritage status, contributing to the largest number of designated heritage sites globally. The introduction of global heritage discourse has profoundly influenced Chinese society over the past forty years, notably reshaping the definition of “cultural heritage” through the formulation of new principles and revisions in cultural heritage laws (Wang & Rowlands, Reference Wang, Rowlands, Geismar and Anderson2017). In 2001, Kunqu opera was designated as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. Furthermore, the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage was adopted in 2003, and China ratified this international convention the following year, thereby introducing the concept of “intangible cultural heritage (Fei wuzhi wenhua yichan 非物質文化遺產).” According to the UNESCO convention, ICH includes five domains:

oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the ICH;

performing arts;

social practices, rituals, and festive events;

knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe;

traditional craftsmanship.

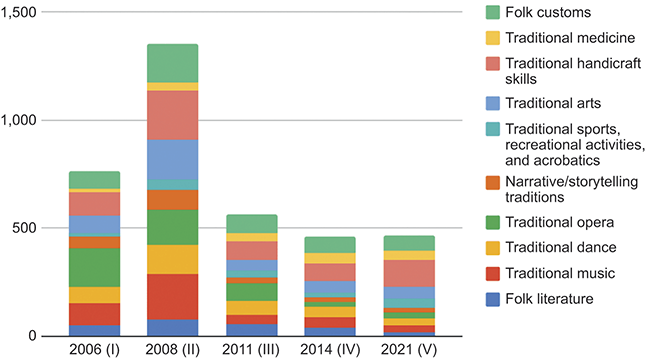

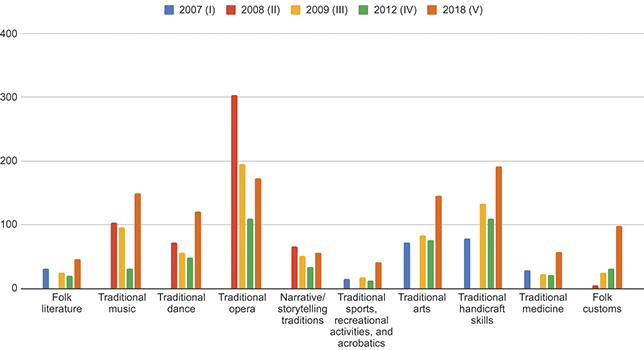

The introduction of ICH into China has facilitated the revival of folk religions, traditions, and customs that were previously restricted, but are now rebranded and protected under the framework of “cultural heritage.” In 2005, the Chinese government officially issued two documents: the Opinions of the State Council General Office on Strengthening the Protection of China’s Intangible Cultural Heritage (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2005b) and the Notice of the State Council on Strengthening Cultural Heritage Protection (State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2005a). These documents were aligned with UN conventions and marked the nationwide initiation of the application and evaluation process for “national-level” ICH projects. By July 2024, China had announced five batches of national-level ICH lists in 2006, 2008, 2011, 2014, and 2021, comprising a total of 3,610 items (Table 1, Figure 1). The concept of “heritage bearers (or inheritors) (Fei wuzhi wenhua yichan chungchenren 非物質文化遺產傳承人)” was introduced alongside ICH. By 2024, five batches – selected in 2007, 2008, 2009, 2012, and 2018 – had been established, totaling 3,057 national heritage bearers (Figure 2). China employs four levels of protection and selection – national, provincial, city, and county – in the designation and safeguarding of ICH. The National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage is established through successive applications and evaluations based on provincial-level lists, ultimately receiving approval from the State Council, denoting its national significance. In 2011, the Law of the People’s Republic of China on Intangible Cultural Heritage (2011) was passed, providing a more comprehensive legal framework for the protection of ICH.

Figure 1 Table of the five lists of ICH in China, updated through 2024.

Figure 2 Number of representative inheritors of national ICH in China, updated through 2024.

Table 1 Number of entries in the five lists of ICH in China, updated through 2024

| 2006 | 2008 | 2011 | 2014 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (I) | (II) | (III) | (IV) | (V) | |

| Folk literature | 53 | 79 | 58 | 40 | 21 |

| Traditional music | 100 | 208 | 44 | 49 | 30 |

| Traditional dance | 74 | 139 | 65 | 46 | 32 |

| Traditional opera | 181 | 161 | 77 | 26 | 28 |

| Narrative/storytelling traditions | 54 | 90 | 31 | 18 | 20 |

| Traditional sports, recreational activities, and acrobatics | 18 | 52 | 31 | 23 | 42 |

| Traditional arts | 77 | 182 | 46 | 54 | 58 |

| Traditional handicraft skills | 112 | 224 | 90 | 80 | 123 |

| Traditional medicine | 13 | 40 | 36 | 48 | 45 |

| Folk customs | 81 | 177 | 89 | 79 | 66 |

| Total | 763 | 1 352 | 567 | 463 | 465 |

Notably, within China’s ICH categories there are ten items: folk customs; traditional medicine; traditional handicraft skills; traditional arts; traditional sports, recreational activities, and acrobatics; narrative/storytelling traditions; traditional opera; traditional dance; traditional music; and folk literature. Many elements of these, particularly those related to religious practices and ethnic traditions, which were once dismissed as superstitions in favor of modernity during the New Cultural Movement (1915) and the May Fourth Movement (1919), are now recognized as part of ICH. With the gradual political loosening following the 1978 opening-up, folklorists began to study folk beliefs more openly (Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). However, during this period, the study of folk beliefs – incorporated into the broader folklore tradition – often concentrated on rites of passage, funerals, temple festivals, and material culture rather than on the “religions” themselves (Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). As noted by Chen (Reference Chen and yu wenhua bianjibu2010), during the 1980s when the state launched the “Chinese Folk Literature Integration Project,” local cultural practitioners faced uncertainties regarding the categorization of folk beliefs and religion under the religious policies of that era, posing challenges for researchers. It wasn’t until the 2000s that this field truly flourished within the discourse of ICH, and folk beliefs have been allocated a specific place in national discussions through a series of national surveys of ICH (Chen, Reference Chen and yu wenhua bianjibu2010; Gao, Reference Gao2007; Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). This inclusion of traditional festivals and folk rituals in the national lists of ICH under the “folk customs” section has sparked a new discourse in folklore studies regarding the relationship between folk beliefs and ICH. Within this new framework, religious practices are sometimes categorized under festivals such as temple fairs and traditional festivals, and at other times under narrative traditions, dance, or music.

In addition to the institutional framework, there were political motivations for promoting the revival of folk religions, particularly those that could strengthen national identity among the Chinese people and overseas Chinese communities. As described by Wu (Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009) and Ku (Reference Ming-chun, Akagawa and Smith2018), in the early 1980s, for example, with Mazu belief being one of the most popular religious practices and goddess figures in Taiwan, and following mainland China’s opening to the world in 1978, many Taiwanese embarked on pilgrimages to Mazu’s hometown in Fujian and to Mazu temples predominantly in southern China. This prompted the mainland Chinese government to emphasize and promote the study of Mazu. The revival of Mazu belief began, under the guise of “folk culture” or “folk belief,” to replace “superstitions,” with Mazu worship in Fujian becoming a symbol of “Fujian-Taiwan folk culture” in mainstream media discourse from 1983 onwards. The Mazu ceremony was nominated for inclusion on the first list of national intangible heritage in 2006, and later “Mazu belief” was recognized as UNESCO ICH in 2009, marking the first instance of a folk belief or religion from China to achieve such status. This recognition undoubtedly carries a significant political message.

Remote ancestral cults, which sought to identify a common ancestor for the Chinese people and to integrate them into a grand historical narrative of ancient Chinese history, were among the first to receive official recognition within the new framework of ICH. For example, the first list, compiled in 2006 with seventy items, includes eleven related to religious practices, mostly focusing on common ancestral cults such as the Huangdi, Yandi, Dayu, Fuxi, Nüwa, Confucius, and Genghis Khan. After the first designation, in the 2006 Handbook for the Survey of Intangible Cultural Heritage in China by the China Arts Center, folk religious practices are listed among sixteen items included in ICH (Chen, Reference Chen and yu wenhua bianjibu2010). This handbook serves as the basis for ICH designation across cultural departments nationwide. Viewing folk beliefs through the lens of ICH enables complementary research into the rituals and customs associated with these beliefs, thereby highlighting their cultural significance and reinforcing their legitimacy (Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). It is through this step-by-step process of study and designation that the Chinese state openly acknowledges folk beliefs as part of ICH.

Religious Revivals in China

Since the early twentieth century, the question of how to define “religion” in state discourse has been contentious. Chinese folk religions, known as Minjian Xinyang (民間信仰), are referred to by various English terms such as religion, folk beliefs, popular cult, popular religion, and communal religion (Chen, Reference Chen and yu wenhua bianjibu2010).Footnote 1 They incorporate sources from Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Legalism traditions. During the Republican era (1911~1949 in mainland China), folk religious practices and Confucian ideology were viewed as hindrances to progress and modernity. Even in the late Qing period, many Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian temples were converted into public or private schools as part of reform efforts to adopt Western knowledge and science. In 1949, with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese Communist Party, as atheists, attempted to outlaw religious beliefs, viewing all religious activities, including ancestral worship, as feudal superstitions. Temples and ritual practices were especially targeted during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when all public religious activities were banned.

However, since the reform era, ancestral worship and folk temples in China have seen a resurgence and signs of prosperity. The revival of folk religious activities began during this period, initially driven by grassroots initiatives, as ordinary people started to revive ancestral worship and temple beliefs (Chau, Reference Chau2006; Gao, Reference Gao2004). These activities were often categorized as tourist festivals or temple fairs, as “religion” continues to be heavily censored by the central state and the bureau of religions. During the 1990s, amid the trend of “culture as the stage, economy as the performance” across diverse regions, local governments increasingly embraced the integration of folk belief activities into temple fairs and cultural tourism initiatives. This strategic approach facilitated the resurgence of traditional practices, including rural temple festivals and other forms of beliefs.

In China, as described by Wu (Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009), the construction of temples follows a standard procedure. Initially, it requires approval from the religious authorities, followed by the issuance of a land use certificate from the land management bureau, and approval of the design plans by the construction planning department. In the 1990s, the various levels of religious administration departments had sufficient policy reasons to reject applications for land use certificates for temple construction plans related to folk beliefs (Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). However, when local governments develop cultural tourism, they often establish temples within museums, memorial halls, tourist attractions, and parks, all managed under the bureaus of culture or tourism, in the name of promoting cultural tourism. Therefore, when applying for land use, they cleverly circumvent the management regulations of religious institutions and other departments, directly using the identity of cultural institutions to construct a legal cultural rationale for themselves (Wu, Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009). Due to temples being designated as tourist attractions and charging high entrance fees, only visitors who purchase tickets can enter. This has led to criticism that religions are being used as a stage for tourism performances.

Gao (Reference Gao2004) has revealed how the “Dragon Brand Association (龍牌會)” in Hebei built up a “temple” in the name of a “museum” under the efforts of folk traditional belief organizations, scholars, and local literati to achieve the legitimate acquisition of folk temples. Through the study of the Black Dragon King Temple in northern China, Adam Chau (Reference Chau2006) explores the interaction patterns between local temples and local governments, including how grassroots religious revivals involve villagers in reviving religious practices and building local temples, as well as the adjustments and controls exerted by local governments. In his book The Temple of Memories: History, Power, and Morality in a Chinese Village (Reference Jing1996), Jing explores the reconstruction of an ancestral hall in Dachuan (大川), Gansu (甘肅) Province, focusing on its transformation into a Confucius Temple and examining the difficulties and strategies employed by villagers during the rebuilding process.

While local communities revived folk temples and their associated customs from a bottom-up surge, local governments incorporated them into their cultural and economic development, primarily through tourism. On a broader level, the central state, prior to the 2000s, did not actively interfere or enforce strict regulations, perhaps recognizing the role that folk religion could play in moral regulation (Madsen, Reference Madsen2014). These spontaneous revivals of folk religion have provided significant spiritual solace to the people during the transition from communist political ideology to the Reform and Opening-Up period. Jing (Reference Jing1996) examines how memory, power, and moral authority within the village were reflected in the temple rebuilding project between the 1980s and the 1990s, showing how historical narratives and local identities evolve and interact over time. Jing (Reference Jing1996) reveals how Dachuan villagers use “memory” to rebuild social relationships and adapt to challenges, impacting the revival of folk religion and the restructuring of rituals. For example, a key innovation in the reconstruction of the ancestral hall was the creation of a new Confucius Temple, which expanded ancestor worship – initially reserved for the Kong descendants from Dachuan (大川) – to include all villagers in 22 nearby villages (about 20,000 people). In the process of creating Confucius statues, the Kong family unintentionally transformed their ancestor into a non-ancestral deity. By identifying as descendants of Confucius, they turned the exclusive practice of ancestor worship into an inclusive Confucian ritual for the entire village. This effort was driven by a growing sense of identity, spontaneous social groups, and community self-governance, highlighting how such efforts shape local identity. Madsen’s fieldwork in temples across Handan and Wenzhou illustrates the revitalization of folk religious practices and ancestral shrines, which serve as moral touchstones for societal norms. Similarly, studies by McNeal (Reference McNeal2012, Reference McNeal2015) document the commemoration of figures like Sage King Shun and the promotion of ancestor worship in regions like Wuhan and Hebei Province. Local elites have invested in constructing temples and monuments dedicated to these figures, aiming to bolster local identity and stimulate the regional economy.

It was not until UNESCO’s ICH convention was recognized by Chinese officials in 2003 that these religious activities were officially permitted and integrated into cultural heritage projects across China. With the inclusion of traditional festivals and folk rituals in the “folk customs” section of the national ICH list, the relationship between folk beliefs and ICH has emerged as a new discourse in folklore studies. The recognition of ICH by authorities has led to the revival of traditional practices once considered feudal superstitions, elevating them to the status of cultural heritage. Once an advocate of Marxist ideology and viewing heritage as an obstacle to modernity, China now proudly celebrates its 5,000-year cultural heritage, and religion is not only surviving but flourishing (Johnson, Reference Johnson2017; Madsen, Reference Madsen2014). Despite having the largest population of non-religious individuals and a government that espouses atheism, religious practices continue to thrive. Yet not all traditions and religions are recognized; it is only through obtaining ICH status that they gain official recognition, enhancing China’s global image and influence and portraying the nation as culturally continuous. Otherwise, they continue to be dismissed as superstitions. Chinese scholars have noted that approaching the study of folk beliefs from the perspective of ICH grants them a rightful place in public discourse, which is essential for their presentation. Wu (Reference Zhen, Jin and Qiu2009) argued that this approach could legitimize the intangible aspects of folk beliefs. However, Gao (Reference Gao2007) critically observed that when folk beliefs are acknowledged as “intangible heritage,” it further solidifies their identity as “folk culture” and “customary culture,” positioning them as relics of historical traditions and pillars of ethnic memory.

With the resurgence of folk religion during the Reform and Opening-Up period, ancestor worship was the first to experience a revival, and remote ancestral cults were the most widely recognized officially. These ancestral cults, which had been in decline for a century, are helping to foster a sense of pride in lineage and tradition linking individuals to a larger shared historical narrative. Each year, tens of thousands of Chinese return to their hometowns to participate in ancestor worship activities. Despite previous restrictions on many religious practices, the Qingming Festival has been established as a national holiday and recognized as a national-level ICH. As a result, central and local governments, as well as various clans and organizations both within China and abroad, have been allowed and even encouraged to carry out ancestor worship activities.

Belief in the “Yellow Emperor,” for example, which this Element examines, began to resurge in various regions during the 1990s on a relatively localized level. Official recognition of the Yellow Emperor as a common ancestor of the Chinese people began after 2000, with ceremonies gradually established in Shaanxi, Henan, Zhejiang, and other areas under the leadership of provincial governments. The Yellow Emperor ceremonies in Henan, Shaanxi, and Zhejiang were designated as national-level ICH in 2006, 2008, and 2011, respectively. According to legend, the Yellow Emperor is viewed as the common ancestor of the Chinese nation and the creator of Chinese culture. As belief in the Yellow Emperor revived, regions began competing to host national-level worship ceremonies. For instance, Henan Province claims to be the birthplace of the Yellow Emperor and thus asserts exclusive rights to “Huangdi culture.” In contrast, Shaanxi Province emphasizes that the Yellow Emperor was buried there and that official ceremonies have been held since the Tang Dynasty, thus claiming its own authority over “Huangdi culture.” Many other regions use historical records, oral histories, or relics from Huangdi temples to claim their connections to the Yellow Emperor. In fact, there are even competitions among various localities within Henan Province to assert their association with Huangdi culture. Today, the intense competition between regions such as Shaanxi and Henan to host a national-level ceremony and assert control over Huangdi culture highlights the distinctive nature of cultural heritage discourse in China. Beyond this competition, since 2003, numerous localities across China have organized large-scale remote ancestral ceremonies.

Additionally, even party officials are encouraged to visit the sites of remote ancestors as part of their annual training in communism. During my fieldwork in China in 2023, I observed that, aside from the dates of grand ceremonies, individuals, businesses, and government officials – who, as Communist Party members, are typically expected to adhere to atheism – participate in organized group trips to these sites. These visits allow these officials to learn about Chinese history and pay respects to their ancestors as part of their patriotic education. This approach is endorsed by the government as part of its promotion of sites of patriotic education.

Yet these religious revivals are selective, a trend that became particularly evident following the promotion of religious Sinicization (Zhongjia zhongguohua 宗教中國化) in 2012, which was officially endorsed by Xi Jinping in 2015 (Y. Wang, Reference Wang2021; Xinhua News Agency, Reference News Agency2021). There is a noticeable trend of Sinicization of religions, where the religious groups are required to operate under the state’s sanction and to incorporate patriotic education (Y. Wang, Reference Wang2021). In 2018, the Religious Affairs Regulations came into effect, leading to the removal of Catholic crosses and the renovation of mosque buildings. Five approved national religious organizations – Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism – are required to operate within their sanctioned frameworks under the supervision of the National Religious Affairs Administration. State-sanctioned Catholic and Christian churches have been rebranded as “Patriotic Churches” under government oversight. Unregistered religious groups face varying degrees of harassment and destruction. Among the five officially recognized religions in China, there is evident repression of institutionalized religions from “abroad” such as Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism. Examples include the demolition of Christian churches in Zhejiang in 2016 and Henan in 2018, and nationwide crackdowns on Catholicism (Y. Wang, Reference Wang2021). In contrast, indigenous religions like Taoism and Buddhism have been successfully integrated into the Chinese government’s religious framework as they contribute to the broader discourse of fostering nationalism and pride in history and heritage. Within this trend, under the banners of nationalism and patriotism, indigenous religious practices, particularly remote ancestral cults that venerate China’s historical past and strengthen national unity, enjoy broad support compared to other religious practices. These practices are conducted by various levels of local governments.

In summary, religion in contemporary China is being selectively revived, focusing primarily on indigenous religions such as folk beliefs, especially those recognized as ICH. The evolution of these beliefs – from being initially classified as “superstition” to being acknowledged as “folk culture,” and now as part of the expanding concept of “ICH” – represents a significant transformation in the perception and revival of Minjian xinyang.

Internalized Heritage Discourse in China

Thanks to UNESCO’s World Heritage discourse, localities in China are engaged in competitive efforts to establish themselves as the hometowns of “historical figures” by designating sites as heritage. Regional and local governments are striving to register cultural expressions associated with these historical celebrities for intangible heritage status, starting at regional levels and progressing to national and global recognition. Such cultural expressions encompass rituals, dances, music, and oral histories. In recent years, a new cultural form known as “grand ceremony” has emerged. Crucially, these ceremonies are modern inventions that blend historical traditions with contemporary expressions.

Studies have demonstrated that the designation of World Heritage items can enhance national pride and identity (Yan, Reference Yan2018), promote tourism and economic development (Zhu & Maags, Reference Zhu and Maags2020), and cultivate new forms of heritage consumption (Zhu, Reference Zhu2018). However, despite these comprehensive studies on heritage in China, there remains a gap in explaining why the Chinese state is more assertive in designating cultural heritage compared to other nations, as well as the intense competition among Chinese localities for these designations. My research reveals a distinct internalization of heritage discourse within China. While the central government ambitiously participates in the global heritage arena by nominating World Heritage Sites, adhering to international conventions, and redefining the legal definition of heritage according to global standards, localities within China are utilizing heritage designations domestically to redefine themselves. Political scientists have analyzed how gross domestic product (GDP) targets foster competitive regionalism. I argue that this competition also manifests in the cultural realm, particularly in the formal recognition of heritage sites. In this Element I explore how local competition shapes the construction of heritage and transforms religious practices, ultimately contributing to the development of new historical narratives that support regional identities.

Since the revival of ancestor worship and the discourse on UNESCO heritage after the Reform and Opening-Up period, the worship of the Yellow Emperor has become widely revitalized since the 2000s. Interestingly, today, various provinces in China are vying for ownership of “Huangdi culture” as if it were a possessable entity. In 2005, the government of Shaanxi Province designated the Yellow Emperor’s ceremonies held within the province as provincial-level ICH, and included them in the national-level ICH the following year. Similarly, ceremonies honoring ancestors organized by Henan Province in Xinzheng City have been led on a large scale by the provincial government since 2006, and were recognized by the State Council as national-level ICH in 2008. Jinyun’s Yellow Emperor ceremony in Zhejiang Province was recognized as national-level ICH in 2011. All three provinces claim legitimacy in their worship of the Yellow Emperor. Other areas, such as Zhuolu in Hebei Province, Zhengning (正寧) in Gansu Province, and Qufu (曲阜) in Shandong (山東), are also vying for ownership of Huangdi culture. As Sangren (Reference Sangren2000, p. 16) noted, “history becomes a heavily ideologically inflected discourse complexly embedded in the sometimes congenial and sometimes strained relations between localities and the state.”

Rivalry among Localities

As part of the revival of ancestor worship and folk religion in Reform Era China (1978–), the 1990s saw a resurgence in popular religion, including the localized worship of Huangdi in various places. Since the 2000s, there has been a growing trend for localities to connect their regions with remote ancestors, revered deities, and/or famous historical figures. For example, Henan’s Zhoukou Huaiyang (周口淮揚) and Gansu’s Tianshui (天水) both claim the legacy of the remote ancestor Fuxi. Similarly, Shanxi’s Linfen (山西臨汾), Hebei’s Handan Shexian (邯鄲涉縣), and Gansu’s Qinan (秦安) compete over the legacy of the remote ancestor Nüwa. Hunan’s Zhuzhou Yanling (湖南株洲炎陵), Shanxi’s Gaoping (高平), Shaanxi’s Baoji (寶雞), and Henan’s Shanqiu (商丘) vie for the heritage of Emperor Yan. Hunan’s Ningyuan (寧遠) and Shanxi’s Yuncheng (運城) contest over Emperor Shun, while Henan’s Luyi (鹿邑) and Anhui’s Woyang (安徽渦陽) compete for the title of Laoyi’s hometown, to name just a few. Even for historical figures like Zhuge Liang (諸葛亮), there are competing claims to his legacy. Shandong’s Linyi (臨沂) asserts itself as his birthplace, while Henan’s Nanyang (南陽) and Hubei’s Xiangyang (襄陽) vie for recognition as his established residence. Furthermore, Shaanxi’s Hanzhong (漢中) claims to be his burial site. Despite these distinctions, all these locations vie for the right to honor and assert ownership of this historical figure’s legacy. These places all compete with each other, claiming exclusive rights to the cultural heritage associated with their locations, and the governments organize large-scale ceremonies to honor these ancestors. Additionally, they are applying for ICH designations for customs, festivals, and legends (oral histories) related to these figures at various levels.

Despite the extensive historical sources and legends about Huangdi, as well as the numerous temples dedicated to him across China, several localities are now competing for ownership of “Huangdi culture,” treating it as a brand to be possessed. Each region uses different historical sources to justify its exclusive claim to Huangdi culture. For instance, Xinzheng in Henan cites the “Bamboo Annals (竹書紀年)” as evidence of the Yellow Emperor’s hometown, while Qufu in Shandong refers to the “Records of the Grand Historian (史記).” The competition extends to claims about the Yellow Emperor’s burial site. Huangling County in Shaanxi points to the “Records of the Grand Historian: Basic Annals of the Five Emperors,” which states: “The Yellow Emperor passed away and was buried at Mount Qiao.” Zhengning County in Gansu also cites this record but claims that Mount Qiao within Gansu is the true burial site. Zhuolu County in Hebei asserts that it was the location of the Yellow Emperor’s battle against Chiyou and cites the “Commentary on the Water Classic (水經注)” to suggest that Zhuolu has historically been a site of Huangdi worship. This competition for legitimacy is widespread among contemporary provinces such as Xinzheng, Qufu, Huangling, Zhuolu, Zhengning, and Jinyun, all of which host official ceremonies honoring the Yellow Emperor and feature statues recognized as part of ICH. In this context, various regions of contemporary China are engaged in a fierce competition using their respective historical documents to lay claim to the legacy of the Yellow Emperor. They not only compete for the legacy of the Yellow Emperor’s existence in various provinces but also contest the legitimacy of their places as the traditional sites for worshipping the Yellow Emperor over dynasties.

In this Element I argue for an internalization of heritage discourse in China, where localities brand themselves with heritage status. It is evident that localities are competing to brand themselves through promoting various ancestral cults and by designating heritage statues. I further present how contemporary China is undergoing extensive placemaking processes alongside the heritagization processes (Wang, Reference 72Wang, Brumann and Berliner2016). These places have all undergone large-scale placemaking, including the creation of large parks, the erection of monuments, and the establishment of temples and museums. In China, placemaking is marked by a fervent desire to brand localities with heritage labels, mirroring UNESCO heritage initiatives aimed at culturally branding locations. As part of attaining heritage status, places are defined by their distinctive “culture (文化 wenhua).” I argue that, in China, localities act as collective entities, treating cultural heritage as proprietary and utilizing it to define themselves, thereby asserting ownership over designated heritage “culture” (e.g., Handler, Reference Handler1988). This Element illustrates how cultural heritage functions as a “name card (名片 mingpian),” strategically used by localities to distinguish themselves. Moreover, official cultural heritage status is employed to authenticate historical narratives as localities cultivate their local and regional consciousness through heritage-making, effectively reshaping history.

3 The Search for a Common Ancestor

The Search for a National Past

In the late nineteenth century, the establishment of nation-states in Europe heightened people’s demands for allegiance, and, as a result, collective memory became a catalyst for national fervor (Olick, Reference Olick2007). Koselleck (Reference Koselleck1985) illustrated that during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Europe saw the emergence of a new historical consciousness, characterized by what he termed “collective singularity.” This shift in historical consciousness moved beyond isolated events to encompass broader historical periods (Geschichte), and from a retrospective focus on the past to a prospective consideration of the future. Individual historical narratives gradually coalesced into a collective understanding, fostering an imagined history. Furthermore, Gadamer (Reference Gadamer1994) introduced the concept of “historically affected consciousness,” suggesting that individuals are influenced by the historical and cultural contexts that have shaped them, whether or not they are consciously aware of these influences.

In a similar vein, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, China underwent a transformation from an imperial system to a modern nation-state, which brought forth a new perspective on its past. Intellectuals grappled with questions about the essence of China’s historical legacy and how to construct a national history suitable for the modern era. Concurrently, there was a surge of public interest in Chinese autochthonous ancestors. Liu (Reference Liu2019) contends that this transition propelled traditional historiography toward modern methods, marking a significant shift in how history was written. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century that scholars endeavored to formulate China’s first chronological calendar, marking a pivotal moment in the formalization of Chinese historical chronology.Footnote 2

This process echoes Benedict Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1983) concept of imagined communities, which emphasizes the role of print capitalism in the formation of modern nations. Anderson argues that print media – particularly the spread of newspapers, books, and other forms of mass communication – played a crucial role in standardizing language, creating a shared sense of belonging, and fostering national identity. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was recognized that there was a need for a unified national narrative, to enable nation building; this prompted historians and archaeologists from the twentieth century onward to delve into the origins of Chinese civilization. This quest aimed to establish a linear historical trajectory, delineate national ethnicities, and demarcate national boundaries. Over time, diverse individual histories and regional narratives amalgamated into a cohesive national timeline, as described by Duara (Reference Duara1995). He argues that national history constructs a semblance of unity for nations embroiled in complexity and uncertainty, presenting a consistent national subject evolving through time.

At this pivotal moment of political and social transformation, beginning in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, there was a notable surge in public enthusiasm for Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor. But who exactly was Huangdi? As a legendary figure from antiquity, Huangdi is surrounded by multiple origin stories and associations. One prominent narrative holds that approximately 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, Huangdi founded the first Chinese nation by triumphing over the evil king Chiyou and his counterpart Yandi (Liu, Reference Liu1999). Revered as the foremost leader among ancient sages, Huangdi is credited with pioneering agriculture, establishing the lunar calendar system, advancing medicine, and developing techniques in weaving, pottery, clothing, housing, and currency – attributes that earned him the title of the founding father of Chinese civilization.

The Yellow Emperor in Historical Narratives

In his works, Michael Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1991, Reference Herzfeld1997) argues that history is not remembered and represented neutrally or objectively but is shaped by social, political, and cultural forces. Using Greece as a case study, he explores how societies “imagine” history, shaping the past to serve contemporary needs. Herzfeld contends that historical imagination is a dynamic, selective process influenced by power, social context, and cultural practices. He emphasizes that historical narratives are actively constructed, not passive reflections of past events, and play a crucial role in shaping collective identity, memory, and political power. Herzfeld highlights how individuals and communities use historical memory to navigate contemporary life and construct national identities.

Similarly, the historical narratives surrounding the Yellow Emperor, both in ancient Chinese texts and today, reveal how his portrayal has evolved over time. The discourse surrounding him traces back to the ninth century and has since reached a new peak, taking on a contemporary form in the present day. His position within China’s “Five Emperors” and “Three Sovereigns” has also shifted multiple times throughout history. Chinese popular discourse holds that the Yellow Emperor is considered the common ancestor of the Chinese people and the founder of Chinese culture. However, records about the Yellow Emperor only appeared during the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States periods (770–221 BC). Records of “ancestors” in pre-Spring and Autumn works like “The Book of History (尚書)” and “The Book of Odes and Hymns (詩經)” trace back at most to sage Yu (禹) and Houji (后稷) (Sun, Reference Sun2000, p. 69). Western Zhou (1046–770 BC) inscriptions trace ancestors no further back than King Wen (文王) and King Wu (武王). The Yellow Emperor only began to be widely mentioned in documents from the Warring States (475/403–221 BC) to the early Han Dynasty (202 BC–AD 220). Initially, he was listed alongside ancient emperors such as Fuxi, Gonggong (共工), and Shennong (神農). It wasn’t until the first century BC that the Han historian Sima Qian, in the “Records of the Grand Historian,” established him as the first ancestor among the Five Emperors of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.

The portrayal of Huangdi (the Yellow Emperor) in ancient Chinese texts has undergone significant transformations, and the sequence and the identification of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors as common ancestors of the Chinese people have also changed over time. During this period, systematic theories about the Five Emperors emerged from works such as the “Annals of Lü Buwei (呂氏春秋)” and “The Master of Huainan (淮南子).” The Five Emperors mentioned are Taihao (太皞), the Yan Emperor, the Yellow Emperor, Shaohao (少皞), and Zhuanxu (顓頊). Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian” lists the Five Emperors as the Yellow Emperor, Emperor Zhuanxu, Emperor Ku, Emperor Yao, and Emperor Shun. The “Greater Rites of the Han Dynasty: The Virtues of the Five Emperors (大戴禮記)” also adopts the theory of the Yellow Emperor, Emperor Zhuanxu, Emperor Ku, Emperor Yao, and Emperor Shun as the Five Emperors.

The name “Three Sovereigns” first appeared in the “Annals of Lü Buwei.” The “Records of the Grand Historian: Annals of Emperor Qinshihuang” states that after Emperor Qinshihuang annexed various states, his ministers suggested that Qinshihuang’s achievements surpassed those of the Five Emperors, unprecedented since ancient times, making him Grand Sovereign. In the Han Dynasty, the apocryphal texts “Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋瑋)” and “Sequence of Fate (命歷序)” made the Three Sovereigns the Heavenly Sovereign (天皇), the Earthly Sovereign (地皇), and the Human Sovereign (人皇). Later, Han Confucians gradually abandoned the titles of Heavenly Sovereign, Earthly Sovereign, Grand Sovereign, and Human Sovereign, pairing the “Three Sovereigns” with ancient emperors. Most theories included Fuxi and Shennong, with the third being Nüwa, Suiren (燧人), Zhu Rong (祝融), or Gonggong. As for the “Records of the Grand Historian: Annals of the Three Sovereigns,” it was supplemented by Sima Zhen (司法貞) of the Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907) describing the Three Sovereigns as Fuxi, Nüwa, and Shennong. According to the “Records of the Grand Historian” annotations by Tang Dynasty scholar Huangfu Mi, “Fuxi, Shennong, and the Yellow Emperor were the Three Sovereigns,” while the Five Emperors were Shaohao, Zhuanxu, Ku, Yao, and Shun (the Yellow Emperor became one of the Three Sovereigns, and Shaohao joined the Five Emperors). Yuan Dynasty temples of the Three Sovereigns also adopted this theory, establishing Fuxi, Shennong, and the Yellow Emperor as the Three Sovereigns.

The evolution of Huangdi’s image from a historical to a legendary and mythological figure illustrates the dynamic nature of historical narrative construction. Initially, Huangdi appears sporadically in texts from the Warring States period, gaining prominence during the early Han Dynasty through the works of historians like Sima Qian. Sima Qian’s “Records of the Grand Historian” formalized Huangdi as a central ancestral figure, integrating him into the genealogical framework of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. The concept of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors also shifted over time, with various texts and scholars proposing different configurations. In works like “Annals of Lü Buwei” and “The Master of Huainan,” the Five Emperors include Taihao, the Yan Emperor, the Yellow Emperor, Shaohao, and Zhuanxu, each associated with different elements and seasons. Sima Qian’s list of Five Emperors – Huangdi, Zhuanxu, Ku, Yao, and Shun – became widely accepted. The Three Sovereigns, initially mentioned in “Annals of Lü Buwei” included figures such as Fuxi, Nüwa, and Shennong. During the Tang Dynasty, Sima Zhen’s supplementation of “Records of the Grand Historian” further elaborated on these figures, incorporating them into a cohesive historical narrative.

By the late Qing period, the study of Huangdi and the broader mytho-historical framework had peaked, with global sinologists examining and debating his origins. During this time, many Chinese intellectuals worked on developing history as a modern discipline, distinguishing it from “myth (神話),” a concept introduced from Japan in the early twentieth century. This distinction between myth and history introduces a new temporal understanding of remote “history.” Influenced by Western scientific and critical approaches, scholars like Gu Jiegang (顧頡剛), Ch’ien Mu (錢穆), and Hu Shi (胡適) critically examined the authenticity of Chinese historical records, often dismissing early history as mere mythology. Known as the “School of Doubting Antiquity (疑古學派),” this group critically examined and questioned the authenticity of ancient Chinese historical texts and traditions. They argued that many ancient texts were mythologized or written long after the events they described, casting doubt on their reliability. Gu Jiegang, a leading figure in this movement, encouraged a scientific perspective on ancient texts and figures. He questioned whether Huangdi was a historical figure mythologized over time or a mythological ancestor humanized and historicized. This movement gained prominence in the early Republican period (1912–1949) and continues to exert influence today. It encouraged a more critical and analytical approach to history, moving away from the uncritical acceptance of traditional narratives. However, it faced controversy, with some scholars and traditionalists criticizing it for undermining Chinese cultural heritage and national identity. The debate between traditionalists and skeptics continues to shape Chinese historiography. This ongoing challenge in Chinese historiography involves differentiating between myth and history and determining which sources to trust.

On the other hand, the late Qing and early Republican eras were periods of significant transition, marking the shift from imperial China to the establishment of a modern nation-state. During this time, there was a growing need to define national ethnicity and establish a continuous national history. Although the Chinese imperial project had long distinguished between the “civilized” Han people and “barbarians” (Dikotter, Reference Dikötter1992), Western ideas of race and ethnicity were introduced to China in the late nineteenth century (Yang, Reference Yang2010). This led Chinese intellectuals to reassess Chinese ethnicity.Footnote 3 For example, late Qing intellectual Liang Qichao (梁啟超) identified the Chinese people as the “Yellow race” (黃種) after learning that Europeans used the color yellow to symbolize China. This symbolism popularized terms like the Yellow River, Yellow land, Yellow race, and Yellow Emperor to refer China (Yang, Reference Yang2010).

A significant development in the historiography of ancient China occurred with the establishment of the Yellow Emperor Era chronology by Liu Shipei (劉師培) in 1903. Liu, a late Qing intellectual, dated Huangdi’s birth to 2711 BC in the Gregorian calendar (Cohen, Reference Cohen2012, p. 4). This chronology aimed to systematize the origins and evolution of the Han race and Han culture, linking historical events to specific dates and reinforcing a sense of continuity in Chinese civilization. Liu’s work sought to reclaim and redefine Chinese identity amid modernization and foreign influence, positioning Huangdi within a historical timeline and emphasizing the deep roots of Han culture. This dating is one of several speculative dates for Huangdi’s era, reflecting ongoing efforts to align myth with history. Liu’s chronology is significant not only for dating Huangdi’s birth but also for constructing a cohesive narrative of Han origins, focusing on kin relationships and cultural development.

This evolution reflects the complex interplay between myth, legend, and historical record in the construction of cultural and national identity. This ongoing scholarly discourse reflects the complexities of distinguishing history from myth in the construction of cultural heritage and identity. The narrative of Huangdi exemplifies how ancient figures can be reshaped to meet the evolving needs of historical memory and cultural symbolism.

Official Worship of the Yellow Emperor in Imperial Times

Throughout imperial China, sacrificial ceremonies of the Yellow Emperor were divided into official worship (公祭) and private worship (民祭). Official worship refers to state-sponsored sacrificial ceremonies organized by the government or official institutions to honor ancestors, deities, or significant historical figures. These public sacrifices are often attended by officials, involving elaborate rituals, music, dance, and other ceremonial elements. They are conducted on a large scale and reflect the collective reverence of the state or community. Examples include state ceremonies held to honor the Yellow Emperor, Confucius, and other important cultural and historical figures. For example, in imperial times, the official worship of Confucius was a highly formalized and significant state ritual known as the “Confucius Worship Ceremony” or “Sacrificial Rites to Confucius” (祭孔大典). This ceremony was an important part of the state rituals and was conducted with great reverence and precision. The main ceremony took place at the Confucius Temple in Qufu, Shandong Province, Confucius’ birthplace, or at the capital where the emperor, as the main host, presided over the ceremony alongside the Minister of Rites. Similar ceremonies were held at Confucius temples across China, conducted by various levels of administrative officials (Huang, Reference Huang2015).

Ritual offerings included sacrificial animals (such as oxen, sheep, and pigs), wine, grains, silk, and other items. These offerings were presented on an altar before the spirit tablets of Confucius and his notable disciples. The ceremony featured ancient ritual music and elaborate dances known as the Six Rows Dance, performed by dancers in traditional attire. The music was played on classical instruments such as bells, chimes, and flutes.

Incense was burned, and prayers were recited to honor Confucius and seek blessings for the state, its people, and the cultivation of moral virtues. Passages from Confucian classics, such as the “Analects (論語)” and other important works, were recited as part of the ritual to underscore the importance of Confucian teachings. The ceremony was rich in symbolism, reflecting the core values of Confucianism such as respect for hierarchy and the importance of education, moral integrity, and social harmony. The emperor’s participation signified the state’s endorsement and promotion of Confucian values as the guiding principles of governance and society. The official worship of Confucius in imperial times was not just a religious or cultural event but also a political statement, reinforcing Confucian ideology as the foundation of the Chinese state and its governance.

When the emperor served as the host, it represented the highest level of official worship. From the Han Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty, the state’s official worship of the Yellow Emperor began to become standardized, with only minor details changing across different dynasties. Generally, there are three main aspects: (1) the Yellow Emperor was included in the grand rites of sacrificing to heaven and Earth as one of the celestial deities; (2) the Yellow Emperor was honored in the imperial temples dedicated to successive emperors, as one of the revered imperial figures; and (3) the Yellow Emperor’s mausoleum was venerated as one of the royal tombs.

According to Liao (Reference Liao2016, pp. 513–514), Emperor Xiaowen (孝文帝) (AD 467–499) of the Northern Wei Dynasty was a key initiator in the state’s official veneration of previous sovereigns and sages, and became the origin of state rituals for earlier emperors from the Sui and Tang dynasties onward. During the reign of Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei to Emperor Xuanzong (宣宗) of the Tang Dynasty, it was found that not only did the rituals become increasingly stable but the continuity of worship of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors was also highlighted through the inclusion of Emperor Ku in the state sacrificial rites. Liao also emphasizes that the changes and re-confirmations of sacrificial locations are crucial in distinguishing official rites from popular folk altars. However, how these locations were decided remains a question. Liao (Reference Liao2016, p. 538) argues that Emperor Xiaowen’s decisions regarding sacrificial sites and subsequent changes were not based on old or singular criteria but were the result of a balance achieved by inheriting existing traditions and reconciling different theories. Liao’s research has illustrated how the Yellow Emperor has had different representations throughout history, and the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors as the ancestors of the Chinese nation have been referred to differently over time. Temples and tombs established for official and private worship during imperial times have become key sites for today’s grand ceremonies, which are often held competitively to assert their legitimacy.

Private worship refers to informal sacrificial ceremonies performed by individuals, families, or local communities. These private sacrifices are typically smaller in scale and may involve personal or family rites conducted at home, in ancestral halls, or at local temples. These ceremonies are deeply rooted in local customs and traditions and reflect the personal piety and cultural heritage of the participants. Examples include family ancestor worship during festivals such as Qingming Festival, Double Ninth Festival, or personal offerings at local shrines. Both official and private acts of worship illustrate the structured and regulated nature of ritual practice in imperial China, balancing the need for reverent observance with practical considerations that could necessitate temporary exemptions.

The Yellow Emperor in Popular Religious Discourse

As observed by many anthropologists studying China, the elevation of notable individuals into lineage genealogies (e.g., Faure, Reference Faure2007; Siu, Reference Siu1990) and their subsequent worship as deities (e.g., Duara, Reference Duara1988) is a defining feature of Chinese ancestor worship. Sangren (Reference Sangren2017) explores Chinese deity cults, arguing that these divine beings often originate from real historical figures. They are enveloped in narratives about their life histories and powers, and are revered by followers who testify to their miraculous abilities. Duara (Reference Duara1988) examined the deification of the historical figure Guan Yu (關羽) (or Guangong 關公), whose image evolved across time and space until he ultimately became a popular guardian deity known as Guan Gong. Originally a general during the late Eastern Han Dynasty, Guan Yu was later deified and worshipped across various sectors of Chinese society, including among martial artists, businesspeople, and politicians. His temples are widespread, found not only throughout China but also in Chinese communities worldwide. Duara (Reference Duara1988) argues that while Guan Yu’s worship is rooted in history, his characteristics and perceived powers have continually evolved over time, shaped by the needs and values of different periods and groups.