These two contributions, the first single-authored and the second an edited volume, push the leading edge of approaches to the study of past politics. How we governed ourselves after the close of the Pleistocene and how we got to where we are today—partitioned into territorial nation-states with a barely controlled impulse towards hierarchy and coercive control—provide the backdrop for both books. The first (by Charles Stanish) takes a more evolutionary longue durée approach to the emergence of social complexity prior to archaic states, while the second (edited by Sarah Kurnick and Joanne Baron) focuses on the strategies of rulership (both inclusionary and exclusionary) that characterised the multitude of archaic states that flourished in Mesoamerica prior to sixteenth-century Spanish incursions. Both books emphatically attempt to move beyond Marxist dialectics of class and power, and are selective in deploying post-modern concepts, such as Foucault’s surveillance and punishment. Most importantly, contributing authors in both books make a concerted effort to ground their ideas about past politics in archaeological case studies. I start with Stanish’s book, move on to the essays about Mesoamerican political strategies and then speak to the larger impact of these works on scholarship of the archaeopolitical.

The goal of The evolution of human co-operation is to provide an explanatory framework for the now countless archaeological sites that defy the logic of the traditional neo-evolutionary framework. Too large, too early, too elaborately non-residential and too riddled with beautifully crafted objects, these ‘anomalous’ sites (as they are called by some) do not fit an evolutionary model of post-Pleistocene humans in lock-step from mobile hunter-foragers to sedentary village dwellers and ultimately to participants in the creation of monumental architecture that is symptomatic of the state. Archetypal examples of such early sites include Göbekli Tepe, Stonehenge, Caral and Poverty Point. What were our ancestors thinking about and doing at these intriguing locales?

The explanation offered by Stanish upsets more than the applecart of neo-evolutionism; he seriously damages population density-dependent models of social evolution, particularly those with a compulsory driver, and he embraces cooperative management of common-pool resources, an idea for which Elinor Ostrom received a Nobel Prize in economics (although her publications are not directly cited in this book). Such cooperative management is not modelled as existing within a leadership vacuum, however; Stanish proposes that managerial-style leaders (not rulers) accrued status through carefully choreographed routines that included conflict resolution, rewards for cooperation (dances, feasts and so forth), and non-coercive censure (primarily ostracism) for non-compliance. The latter effectively dealt with the problem of free-riders, an issue that Ostrom also dwelled upon in her classic Reference Ostrom1990 publication, Governing the commons.

In Stanish’s view, higher population levels enabled (rather than forced) large-scale cooperation, the material record of which is preserved in large, early sites that Stanish refers to as special rather than anomalous (examples reviewed in detail in Chapter 7). The prosocial organisations underpinning these locales subsequently fell apart if/when large-scale defection from seasonal group aggregation occurred. From this perspective, a critical mass of humanity was important, but not because it pushed people across a Malthusian threshold, or forced hierarchy and despotic forms of governance. Stanish pushes back on the notion that rank is inherently immoral.

A material characteristic of special places is the large amount of production debris that archaeological excavations tend to encounter. Evidence of prodigious quantities of stone- and shell-working generally is conspicuous and points to activities that would be labelled unambiguously as economic in other contexts. Why go to a special place to work stone or shell, which might have to be transported hundreds of kilometres from its place of origin? Stanish and others before him suggest that production at these early sites of congregation was ritualised in the sense that where something was crafted may have imbued the objects with a charged quality beyond utilitarian functionality. This line of reasoning is enlarged to include ritualised limits on resource extraction (taboos) and a conscious forging of links between subsistence activities and supernatural forces—thus the subtitle of Ritual and social complexity in stateless societies—is explored through ethnographic vignettes in Chapter 5.

A bottom line of this treatise is that coercion is a characteristic of archaic states and not the complex, stateless forms of social organisation under study in this book. But a lack of coercion does not equate with a lack of intergroup violence, of which there is plenty of archaeological evidence and from which Stanish does not shy (see Chapter 4). Building upon the vocabulary and concepts of game theory, Stanish labels the free agents as conditional co-operators, meaning that participants are not involuntarily bound into a cooperative agreement, but are free to walk away to join another group or scale back their group inclusion and the benefits thereof. Such a prosocial approach to the evolution of complexity surely turns a corner and upends much received knowledge regarding how political change occurred as the world became a more populous place in wake of the last great period of climate change. In the opening chapters (1 & 2), Stanish chronicles the rise and fall of Homo economicus, which might also be understood as the limits of what could be understood when the past is viewed strictly from the framework of modernist Western rationality.

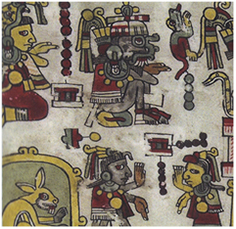

The voluntary and conditional cooperators of the stateless but socially complex society—agents used to a fair deal—become the enigma, the energy and the brakes of archaic states. In Political strategies in pre-Columbian America, contributors focus on the myriad strategies by which Mesoamerican rulers (not leaders) worked to impart a sense of fairness and group solidarity while, at the same time, reinforcing their aura of royal otherness and separateness from their constituents. In the introductory chapter, Sarah Kurnick refers to this paradox as the central contradiction of political authority. Noting the deep history of Western scholarship on authority and legitimacy, Kurnick suggests that rather than pigeon-holing archaic states of Mesoamerica as conforming to a certain authority type, it might be more productive to examine how the contradiction stated previously was negotiated in Mesoamerica and elsewhere as well. Such an approach moves us beyond the threadbare question of why authority structures are accepted and into a more fertile intellectual space in which commoners might be conditional cooperators and rulers may only have a tenuous hold on kingly authority. Each case study in this book, arranged chronologically, circles around the paradox of rulership.

Takeshi Inomata (Chapter 2) dwells on the fragility of rulership by focusing on Formative-period public architecture at the southern lowland Maya site of Ceibal. At a point when the political idea of kingship was only taking shape, Inomata argues that early forms of public architecture—such as E Groups—were built by and for communities, rather than by and for kings. During the Formative period, these places were probably “arenas of negotiation and contestation among diverse parties” (p. 47). The idea of communities as conditional cooperators in the crafting of kingship is reiterated by Arthur Joyce and colleagues in reference to coastal sites from Terminal Formative Oaxaca (Chapter 3). Focusing on negotiation and contestations at Río Viejo, they find ample evidence of large, communal labour projects and feasting, but no ruler’s palace or royal tomb. Analogous perhaps to the ‘special’ places described by Stanish, Río Viejo was “abandoned at ca. 250 CE” (p. 80) and never coalesced into a royal court in the manner seen at Monte Albán in the highlands of Oaxaca.

In central Jalisco, the tension between community solidarity and competition among lineages is detailed by Christopher Beekman who focuses on architectural forms of the Tequila Valley on the cusp of the Late Formative to Early Classic periods (Chapter 4). Ball courts, although arenas of competition, are interpreted by Beekman as a “material manifestation of community ritual oriented towards the higher goal of social and cosmic balance” (p. 103). These constructions are contrasted with shaft tombs that promote the status of specific families through memorialising ancestors.

Joanne Baron (Chapter 5) threads the needle between royal authority and group solidarity by focusing on patron deity shrines in the Classic Maya southern lowlands. Although royal lineages could be highly exclusive, patron deities were group inclusive and provided effective vertical integration at the archaeological site of La Corona and others as well. Baron argues that this form of ritualised group solidarity (I use Stanish’s term here) was manipulated by the rulers of La Corona, who positioned themselves as most capable of interceding with, and nourishing, patron deities. By doing so, rulers of La Corona, and perhaps other royal courts as well, temporarily resolved the central paradox of their otherness and promoted group inclusivity.

The nature of governance at Teotihuacan in central Mexico has never been easy to read from archaeological remains. Yet Tatsuya Murakami brings substantial evidence to bear on the proposition that around 450 CE (Late Xolalpan phase) the governance of Teotihuacan shifted from despotic rulership (characterised by pyramid construction and ritual human sacrifice) to a bureaucracy characterised by non-residential, administrative constructions built along the Street of the Dead (Chapter 6). At the primate capital of Teotihuacan, one of the five largest urban entities globally at this time, another kind of political tension is in evidence. For a large city to retain its occupants—who provide the engine of viability—public goods and services must be organised and provided by public servants awarded for their efforts. The governance of Teotihuacan appears to have been restructured to provide such goods and services in order to ensure its longevity, at least for another 100–200 years.

Bryce Davenport and Charles Golden spatially reframe the tension between community and kingly prerogative by focusing on the moral order of royal ideology and how it was performed and recreated throughout the realm (Chapter 7). Their notion of boundedness is echoed by Helen Pollard in Chapter 8 who observes that Tarascan imperial strategies of Late Postclassic times pursued both “greater social inequality and greater ethnic solidarity” (p. 217). Simon Martin provides a final overview of political theory and things “archaeopolitical” (p. 241), warning archaeologists that political stability is ephemeral, particularly within archaic states.

What is the take-home message of these two books, both eminently worthy of a read and seminar discussion? I think there are three. First, the conditional cooperators exemplified by complex, stateless societies do not disappear when kings manage to carve out sufficient authority to ensure kingly prerogative and regeneration through time. Their presence continues to be a palpable source of tension that is archaeologically visible. Second, there is empirical evidence to support the idea that humans historically have cooperated in large groups in the absence of coercion (and without the state). Third, political strategies are fragile experiments in living as a community, a group, a state or a nation. Riddled with contradiction, such experiments—while important and creative indicators of the human experience—should not be freighted with embellished expectations of longevity.