Background and introduction

States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child. (United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 12.1; ratified by Australia on 17 December 1990)

Australian researchers, in line with a global trend, have demonstrated growing interest in including the voices of children in research and seeking their perspectives on the relevance and effectiveness of the services and supports that are, or should be, available to them (Danby & Farrell, Reference Danby and Farrell2004; Graham & Fitzgerald, Reference Graham and Fitzgerald2010). This paper provides a scoping review of Australian child participatory research published since 2000 across the service sectors that are most directly involved in supporting children: child protection and family law, community, disability, education, health, housing and homelessness, juvenile justice and mental health. It is a descriptive paper, focusing on child and youth engagement in research relating to formal services, with the aim of examining the extent to which the research documents child and youth involvement in service policy, design, implementation and evaluation. Of course, children and young people may engage with system and service change in other ways, such as through quality improvement processes, policy development and community consultation; however, this paper gives focus to those mechanisms documented within a research context. We have chosen a cross-sectoral approach because we are interested in understanding the landscape of Australian child participatory research, in identifying where child and youth voices are absent in research (or the ‘silences’) and in challenging the siloed nature of the service system to understand how the different sectors collectively engage with children and young people and can learn from each other.

Research focused on child perspective and child experience has a long history within sociology and social anthropology (Qvortrup, Reference Qvortrup, Qvortrup, Corsaro and Honig2009). However, it was not until the widespread embrace of the ‘New Sociology of Childhood’ that policy and practice began to respond to notions of child agency and the role of children in decision-making, further reinforced by the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (Tisdall & Punch, Reference Tisdall and Punch2012). The New Sociology of Childhood positions children and young people as critical agents in their own development and in decision-making about the supports they need (James & Prout, Reference James and Prout2015).

Leading Australian researcher, Dorothy Scott, argues that a ‘sophisticated social policy response’ to the fragmented and inefficient nature of services will only come about by a ‘whole of society response’ that ‘draw[s] upon the capacity of children themselves to be, and be seen to be, contributors to the community, rather than merely clients and consumers’ (Scott, Reference Scott2014). The importance of actively engaging young people in the Australian service context was reinforced in the recent recommendations from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Assault (2017), which require that all Australian service providers put in place formal mechanisms to listen to the voices of children and young people. This growing commitment to child participation is ultimately underpinned by Article 12 in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which is a statement not only of their right to be heard on ‘all matters affecting them’ but also to have their views ‘given due weight’ by institutional adult decision-makers (UNICEF, 1989). Children and young people have an important role to play both in service policy and practice. Beyond their legislated right to be heard on the issues that affect them, we know from the literature that children and young people can offer perspectives that build adult capacity in terms of understanding childhood and children’s lives and that these insights are essential to accurately identify the need and the development of service innovation (Kellett, Reference Kellett2010).

The term ‘participation’, for the purposes of this paper, is used broadly to describe research in which children have been involved in one or more of the nine stages of a research study, including: (1) determining the research questions; (2) designing the research and choosing the methods; (3) preparing the research instruments; (4) identifying and recruiting participants; (5) collecting data; (6) analysing the data and drawing conclusions; (7) producing a report; (8) disseminating the report and its findings and (9) advocating and mobilising to achieve policy impact (Shier, Reference Shier, Berson, Berson and Gray2019). It is important to note that the child participatory agenda has been critiqued, particularly as this relates to the notion of agency and the extent to which children’s decision-making is significantly constrained as the result of context, positions of power, life-course stage, so on. Robson, Bell, and Klocker (Reference Robson, Bell, Klocker, Panelli, Punch and Robson2007) argue that agency must be scrutinised, that we should not always assume it is a positive experience for children and young people to share their views and advocate for change, and that we must respect that children and young people have a right to assert their agency in different ways of their own choosing. With that in mind, it is not the intention of this paper to argue that children should be obliged to fill all of the silences in child voice research, as this relates to the Australian service system. The purpose is simply to provide, in one document, an overview of the research that has been undertaken within Australia and identify where there seem to be gaps.

The landscape of Australian child participatory research is broad. Examples of high-quality research exist within the fields of child protection (e.g. Cashmore, Reference Cashmore2002), education (e.g. Dockett & Perry, Reference Dockett and Perry2002), health (e.g. Ford, Reference Ford2011), adolescent mental health (e.g. Davis et al., Reference Davis, Davies, Cook, Waters, Gibbs and Priest2008), juvenile justice (e.g. Ashkar & Kenny, Reference Ashkar and Kenny2009) and new arrivals to Australia (e.g. Nathan et al., Reference Nathan, Kemp, Bunde-Birouste, MacKenzie, Evers and Shwe2013). Also emerging are innovative bodies of research capturing, from their own perspectives, the support needs of young people who are homeless (e.g. Moore, McArthur, & Noble-Carr, Reference Moore, McArthur and Noble-Carr2008) and exploring concepts such as belonging and connection with young people with disabilities (e.g. Robinson & Notara, Reference Robinson and Notara2015). The Australian research literature also includes in-depth studies exploring overarching concepts such as community (e.g. Bessell & Mason, Reference Bessell and Mason2014), wellbeing (e.g. Fattore, Mason, & Watson, Reference Fattore, Mason and Watson2016) and neighbourhood (e.g. Goodwin & Young, Reference Goodwin and Young2013) from the perspectives of children and young people. There is also an extensive grey literature reporting on the work of government and non-government organisations engaged in service development and policy design with children and young people (e.g. NSW Advocate for Children and Young People, 2017). The collective body of both academic and ‘grey’ literature demonstrates that children and young people can competently express their views when asked within the context of a supportive research environment, one in which the power imbalances are directly addressed and the methodologies are age appropriate and flexible in response to the support needs of the child (Fraser, Lewis, Kellett, Ding, & Robinson, Reference Fraser, Lewis, Kellett, Ding and Robinson2004). There is a growing body of literature that directly addresses the challenges associated with child participation in research including, for example, issues around securing informed child consent (Alderson & Morrow, Reference Alderson and Morrow2011) and adult gatekeeping as a barrier to research recruitment (Collings, Grace, & Llewellyn, Reference Collings, Grace and Llewellyn2016). These issues are coming more strongly into focus as the field moves from justifying that child participatory methods are important to a focus on how to support the participation of children and young people well.

The extent to which the views of children and young people are taken into account and given appropriate weight in service decision-making is not straightforward. Certainly, the intent to listen to children and young people is present across Australian government and many service organisations, as evidenced by the consultation structures in place and some key national policy initiatives. For example, the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 recognises the importance of children’s participation. Nonetheless, the extent to which young people are involved in service decision-making processes very often depends on the receptiveness and underlying philosophical approach of the adults directly involved: the caseworkers, teachers, administrators, lawyers, health professionals and early intervention specialists (Berrick, Dickens, Pösö, & Skivenes, Reference Berrick, Dickens, Pösö and Skivenes2015). The known barriers for service providers include concern that children may not have the capacity to express a well-reasoned view and that they can be easily manipulated (Parkinson & Cashmore, Reference Parkinson and Cashmore2008). Some argue that responding to the perspectives of children and young people requires resources their organisation do not have, and others claim that too often the child voices being heard are only those of well-educated, middle-class youth (Bell, Vromen, & Collin, Reference Bell, Vromen and Collin2008). Others are supportive of children and youth sharing their views, but see this as providing a learning opportunity for the children and young people, rather than as a learning opportunity for the service organisation (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Vromen and Collin2008). These concerns suggest that there is a need for child participatory research to consider the extent to which the voices being heard are representative and to explore the most effective models of child and youth engagement and the impactful translation of their perspectives into policy and practice.

This paper scopes the landscape of participatory research on service policy, design, implementation and evaluation in Australia across eight service sectors. It has been designed to answer questions about where child and youth voice is being sought and where it is silent and the extent to which the current research reflects a diversity of cultural and other life experiences. The value of a scoping paper lies in its ability to identify the gaps and prompt new avenues of research enquiry. It is our hope that this paper will contribute to the momentum for participatory research that is growing in the Australian context, with the ultimate goal of engaging children and young people at all levels of policy debate and implementation as we work towards more effective models of service support.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review because our objective was to develop a broad-brush picture of current child participatory research in Australia within a relatively short time frame, requiring the setting of manageable boundaries around our search, as described below. This was a mapping exercise and did not involve assessment of research quality, as required for a systematic review (Armstrong, Hall, Doyle, & Waters, Reference Armstrong, Hall, Doyle and Waters2011). The description of our method has been structured according to the five phases for conducting a scoping review proposed in the Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) framework.

Identifying the research question

Our search of the literature was guided by the following core question: What is the state of current Australian research knowledge on child and youth participation in research undertaken within formal service sectors?

We targeted research designed to directly inform eight service sectors: (i) child protection and family law, (ii) community, (iii) disability, (iv) education, (v) health (excluding mental health), (vi) housing and homelessness, (vii) juvenile justice and (viii) mental health.

Identifying relevant studies

This review includes only studies published in peer-reviewed journals. This criterion serves as a loose proxy for quality control. We are aware that there is an extensive body of ‘grey’ literature in the form of both published and unpublished research reports that describe participatory research with children and young people in Australia (e.g. Bessell, Reference Bessell2011). However, for the purposes of this review, only peer-reviewed journal publications were within scope.

Articles were sourced through online databases. One member of the authorship team took primary responsibility for each of the eight focus areas, with a second team member conducting checks. For each field, we conducted an initial search within Scopus and then a search in at least one discipline-specific database (ERIC for Education; PsycINFO for Child Protection; MEDLINE for Health and Mental Health; CINAHL for Disability; CINCH for Juvenile Justice and SocINDEX for Homelessness, Neighbourhood and Community). Relevant papers were also identified in the reference lists of previously identified papers.

To be included, the following search terms needed to be present within titles or keywords (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Search terms.

The search was also limited to studies published from the year 2000 to 2018. Limiting the timeframe was a pragmatic decision to support the rapid review of recent literature relevant to the current policy context.

Study selection

To be included, the paper needed to meet two inclusion criteria:

1. The paper under review needed to present the perspectives of children and young people aged 18 years and younger. We selected 18 years as the cut-off, reflecting both Australian general law which sees 18 years as marking the commencement of the legal rights and responsibilities of an adult, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, cited above, which guarantees the participation rights of all those under 18.

2. The study needed to employ participatory research methods. We applied a very broad definition of ‘participatory’, requiring that papers report on research that provided an opportunity for children and young people to express their views on the topic at hand, to be treated as social actors whose experiences and opinions were important. This included both qualitative and quantitative studies where participating children and young people were asked to either talk about their views and experiences, present them in a creative form (e.g. photos and drawings) and discuss what their creations represented to them, or give their opinions in a survey form. Very broadly, the research needed to be with or by children, and not on children (i.e. children treated as the objects of study without opportunity to express their own opinions) (Mason & Watson, Reference Mason, Watson, Ben-Arieh, Casas, Frønes and Korbin2014). It was sometimes challenging to make a distinction between studies that only assessed children (were on children), which were not included, and those that sought their views. For example, a study looking at the impact of bullying by assessing child wellbeing using a measure like the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) or the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), even if the checklist was completed by the child, was not included. In this case, while the children were being asked to rate their experiences, they were not being asked to talk specifically about bullying (i.e. giving their views directly on the issue at hand) and it was the researcher, rather than the child, who drew conclusions about the impact of bullying. If, on the other hand, the researchers had included some qualitative or quantitative questions in their design asking the participating children to share their perspectives on bullying and/or its impact, then the study would be included.

We are aware that there are some who would consider our definition of ‘participatory’ too broad. For example, in their 2013 position paper, the International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research described a participatory research design as one in which every step of the research process is fundamentally influenced by the people who are directly impacted by the issue being studied (ICPHR, 2013). Most child voice research in Australia remains researcher-controlled, with those who are directly impacted playing a consultative role by contributing data. Because this is a scoping paper, we have erred on the side of inclusion.

Charting the data

For every paper that met our inclusion criteria, we documented the following variables: (i) the topic area; (ii) the methods used; (iii) the number of participating children and young people; (iv) the age range of the participants; (v) participant diversity and (vi) the nature of child and youth participation in the study.

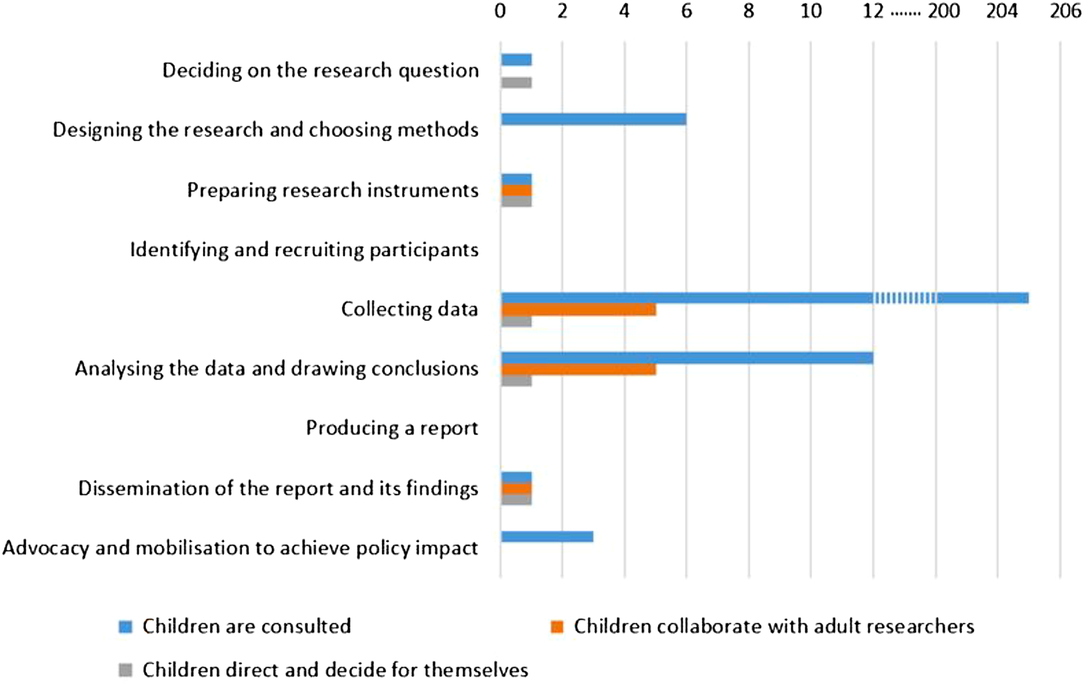

The nature of child and youth participation was determined using the Shier’s participation matrix (Shier, Reference Shier, Berson, Berson and Gray2019), a tool for examining the level of child and youth participation across the phases of a research project, as presented in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Shier’s participation matrix (Shier, Reference Shier, Berson, Berson and Gray2019).

The findings of individual studies were not included in our summary tables. As mentioned earlier, the purpose of this scoping review was to understand what research was being conducted within Australia, how it is conducted and identifying where child and youth voices appear to be absent. It was beyond scope to provide a summary of findings.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The findings have been organised under headings relating to the service system to which they most closely corresponded. A number of studies had been developed to inform more than one service system (e.g. health and education), and in these instances, the paper was assigned to the service system grouping to which it was most strongly aligned.

For each grouping, gaps in the research were identified based on the critical reflections of the 11 members of the authorship team, all of whom brought extensive expertise in one or more of the eight service sector areas reviewed. Given the subjective nature of such judgements, it is hoped that this paper will serve as a catalyst for further dialogue.

A discussion of what we can learn from across the sector groupings is presented. In addition, an analysis of the level of participatory methods collectively represented in the included research according to the Shier’s participation matrix is provided.

Full details of the studies included in the scoping review are presented in the Supplementary material that accompanies this paper.

Results

Part 1. Scoping the research according to service sector groupings

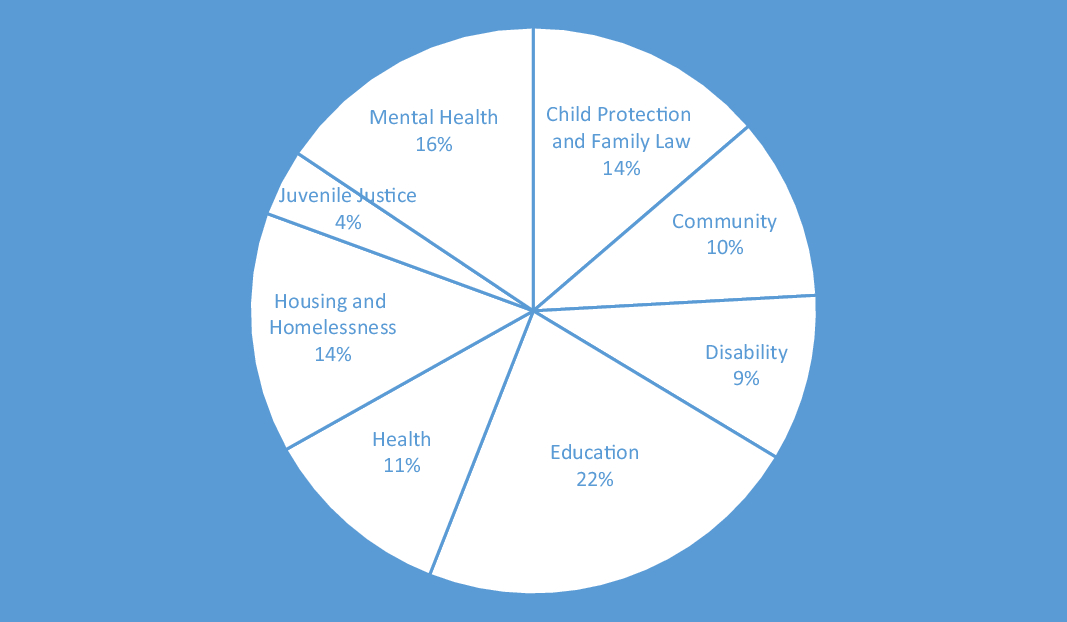

In total, 207 Australian peer-reviewed research papers published between 2000 and 2018 that included the perspectives of children across eight areas of research were identified (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Distribution of Australian child voice research papers across sectors 2000–2018.

Tables summarising the research literature are presented for each sector, followed by our reflections on where there appear to be gaps within the literature. Numbers within the tables are based on the information provided in the papers. Some papers did not provide the detail we were looking for and so could not be counted on some variables, meaning that it is possible that some of the numbers are an under-representation.

Education

The education sector produced the largest number of papers that met the inclusion criteria, with 46 papers identified. These papers were organised under three broad topic areas, as summarised in Table 1: experiences and perspectives on education and schooling; factors impacting on child learning and development; and program participation.

Table 1. Australian child participatory research on education from 2000 to 2018

Under the heading ‘experiences and perspectives on education and schooling’, there was a range of papers giving focus on school transitions, spaces within school settings, and the experiences of young carers and homeless young people and school. Papers identified as relating to ‘factors impacting on child learning and development’ explored issues such as learning through play, education practices and child aspirationalism. ‘Program participation’ consolidated research on topics including the implementation of positive education strategies and the impact of community mentoring programs. A full list of papers is included in the Supplementary material.

The research literature included in the education table engages with a diverse range of children and young people, including Indigenous and CALD children and young people. A broad range of methodological approaches are utilised, most commonly to support the participation of children in the early years who are more strongly represented in the education research than in any other service system grouping, to the point where it could be argued that adolescent voices are under-represented. It should also be noted that there are more papers within the education literature that have sought to utilise a range of participatory approaches across the phases of the research. There are, however, some significant issues relating to school and education that are not addressed in the above literature.

Gaps in the research literature

Following is a list of major topics within education that do not seem to have attracted significant research focus employing child participatory methods based on the papers identified by this scoping review:

The school curriculum, that is, the content of what children are taught in schools

The quality of teaching in schools

Experiences of home schooling

Reward and punishment strategies within the school context, including point systems, detention and suspension

Truancy

Bullying in the school context, peer group dynamics

Early school leavers

Pastoral care and experiences of school counselling services

Perspectives on effective teaching strategies

Views on the Private versus Public School debate

Views on the Co-educational versus Single-sex school debate

Experiences and views on NAPLAN testing

The advantages, disadvantages and pressures associated with opportunity classes (OC) and selective school opportunities

Interactions between home and school environments, including homework, private tutoring and the nature of support required from parents

Gender and sexual diversity issues (e.g. LGBTIQ+) within school settings

Mental health

Thirty-two papers within the mental health field met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. These papers could be organised under two broad topic areas (see Table 2): concepts and experiences associated with mental health; and feedback and insights into service provision.

Table 2. Australian child participatory research on mental health from 2000 to 2018

Papers relating to ‘concepts and experiences of mental health’ explored topics including wellbeing, the impact of drought on mental health, health behaviours and self-harm, and social inclusion. ‘Feedback and insights into service provision’ included research on the engagement of services with vulnerable and disadvantaged populations, supporting children of parents with mental illness, sport programs to improve mental health and the role of technology in assessment and service delivery.

Gaps in the research literature

There are very few young voices represented in mental health research, suggesting the need for further research engagement with children within the early and middle-childhood years on issues relating to mental health and wellbeing. The gaps we have identified, based on our scoping review, include the following topics:

Experiences of young people with mental health issues and their engagement with universal services

Adolescents, mental health and employment

Impact of mental health challenges on family members and family relationships

Self-harm and suicidal ideation

The impact of social media/Facebook/cyberbullying on mental health

Mental health of child and youth from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds

Intergenerational impacts for the children of people seeking asylum

The impact of culture on the perceptions of mental health challenges

How children and youth identify and connect with people in the community who will support them

Mental health of children and youth that identify as LGBTIQ+ and other sexuality, bodily and gender diverse persons

Child protection and family law

We identified 29 papers that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review within the child protection and family law field, as summarised in Table 3. Each paper was reviewed, and three broad topic areas were identified across the papers: experiences of out-of-home care; family dispute resolution, courts and family law; and project or program evaluation.

Table 3. Australian child participatory research on child protection and family law from 2000 to 2018

* Where there was more than one paper reporting on the same study with the same participant group, we counted the participant numbers only once.

Papers that were grouped together under the heading ‘experiences of out-of-home care’ included a broad range of research topics, including looking at issues of identity and relationships within foster families. Papers that were collected together under the heading ‘family dispute resolution, courts and family law’ focused largely on child decision-making in the context of parent divorce. The scoping review identified very few papers reporting on child perspectives relating to the effectiveness of intervention programs. A list of topics that were addressed by the papers included in our review appears within the Supplementary material.

Gaps in the research literature

There were several papers that did not provide detail on the diversity of the participant group, making it difficult to know to what extent the voices shared were representative of diverse cultural and other life experiences. Nonetheless, it appears that research engagement with Indigenous (7 of 29 papers) and culturally diverse (4 of 29 papers) children and young people is low. There is a particularly strong need for more research with Indigenous children, given how over-represented they are within the out-of-home care system. There is a need for more research with children in the early years. The summary table also suggests that there are low levels of engagement with children and young people as this relates to the perceived effectiveness of support programs. There appear to be gaps in the peer-reviewed participatory literature on topics that attract considerable discussion and debate in other research, practice and policy contexts, including:

Experiences of those who transition from foster care to adoption

Experiences of reunification with biological parents

The separation of siblings

Cultural connection and cultural identity for those in out-of-home care

Agency and decision-making

Maintaining connection with extended family, including grandparents and cousins

The effectiveness of trauma-based and other intervention/support programs

Housing and homelessness

We were able to identify 28 papers on housing and homelessness that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review, as summarised in Table 4. These papers could be organised into two broad topic areas: concepts and experiences associated with homelessness; and feedback and insights into service provision.

Table 4. Australian child participatory research on housing and homelessness from 2000 to 2018

* Where there was more than one paper reporting on the same study with the same participant group, we counted the participant numbers only once.

The topic area ‘concepts and experiences associated with homelessness’ included research on general experiences, pathways into homelessness, social relationships and food insecurity. The research papers that fell under the heading ‘feedback and insights into service provision’ were focused on service system responses and service engagement. Research within this field employs a diverse range of methods and included several papers that sought to be participatory in their methods beyond consulting with children in their data collection. The Supplementary material provides the full list of papers.

Gaps in the research literature

Collectively, this body of research is very focused on adolescence, pointing to the need for research that seeks to understand the experiences and support needs of children in the middle childhood and early childhood years. Topics not explored within the papers identified in our scoping review include:

The concept of a ‘street family’

The use of sex to secure accommodation and how to keep safe

Family and extended family connections and relationships

Homelessness and school/education engagement

Homelessness and participation in sport and other recreational activities

Health

There were 23 papers identified from the health literature that met our inclusion criteria. Based on their research focus, they fell within four broad topic areas: concepts and experiences of health; feedback and insights into service provision; aboriginal health; and adolescent health.

Under the ‘concepts and experiences of health’ topic, the research addressed physical activity and sedentary lifestyles. The research papers that were collected together under the ‘feedback and insights into service provision’ heading included research on food choices, hospital environments and treatment compliance. The ‘Aboriginal health’ topic included papers on smoking and general health and wellbeing. ‘Adolescent health’ included research addressing access to health care, emergency contraception and the transition to adult services (see Supplementary material).

Gaps in the research literature

Overall, there is not a lot of diversity represented in the voices included in the papers summarised in Table 5. There is, however, a reasonable spread across the age ranges. This scoping review would suggest that the gaps within the child participatory health literature include the following:

Sexual health and safe sex education

Safe injecting

Public health, rather than, hospital-based research

Screening and immunisations, including awareness of their purpose and consent

Allied health therapies other than music therapy

Experiences of chronic health issues, including childhood obesity

Family and other support services, such as Ronald McDonald House and hospital schools

The experiences of refugees and people seeking asylum accessing and engaging with the health system

Table 5. Australian child participatory research on health from 2000 to 2018

Community

There were 22 papers identified that met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review as this related to research on community (See Table 6). The papers could be organised under two broad topic areas: experiences and perspectives on community; and experiences of participation in community-based programs.

Table 6. Australian child participatory research on community from 2000 to 2018

The papers that were grouped together under the heading ‘experiences and perspectives on community’ described research on children’s experiences of community, neighbourhood and home, as well as social capital and class distinctions. ‘Experiences of participation in community-based programs’ brought together research on a range of intervention programs, including two programs run in remote Indigenous communities (see Supplementary material).

Gaps in the research literature

Our scoping review would suggest there is room for more research, exploring how children in the early years understand and engage with community. One half of the research on participation in community-based programs focused on sport programs. Whilst sport is clearly a very important part of social connection and community, there is a need for research that explores other forms of community engagement, such as through music and the creative arts or through volunteering, and particularly the range of opportunities for children’s play outside the home (other than sports activities) afforded in different communities. There is also room for research that explores the engagement of children and young people in political activism, for example, child involvement in driving change as this relates to environmental policy, and so on.

Disability

Nineteen papers were identified within the disability field as meeting our inclusion criteria, as summarised in Table 7. Based on their focus, they could be organised under two broad topic areas: concepts and experiences of disability; and feedback and insights into service provision.

Table 7. Australian child participatory research on disability from 2000 to 2018

Papers within the ‘Concepts and experiences of disability’ literature addressed issues such as friendship and belonging, social connection and disability within family systems. ‘Feedback and insights into service provision’ included papers on therapy and remediation, satisfaction with assistive technology and appropriate communication within medical settings.

Gaps in the research literature

The literature captured within our scoping review points to a general lack of diversity in the participants who were engaged with disability research. There appears to be under-representation of the voices of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) and Indigenous children and young people, as well as those living in rural and remote areas. Most of the studies are with children in middle childhood, suggesting the need for research that includes the perspectives of young children and adolescents. There is also more research with children and young people who have physical rather than sensory or intellectual disabilities, suggesting the need for the utilisation of more diverse and creative methodologies to ensure that all children have their views taken into account. Our scoping review suggests that there is a need for research with Australian children and young people on the following topics:

Experiences of services other than medical services, including experiences of engagement with mainstream services

Engaging with the physical environment

Child and youth perspectives on families and home environments

Children and young people as carers

Experiences of, and perspectives on, the National Disability Insurance Scheme

Juvenile justice

The juvenile justice field produced the smallest number of research papers that met our inclusion criteria, with eight papers identified. These papers have focus to the following three broad topic areas: risk factors and criminal behaviours; behaviour change and diversionary programs; and feedback and insights into service provision.

The research papers that were collected under the ‘risk and criminal behaviours’ heading addressed relationships between incarceration, family and school factors and offending behaviours. ‘Behavioural change and diversionary programs’ included research on a music program and an injury prevention program. The ‘feedback and insights on service provision’ heading included research such as transition from a juvenile justice facility back into the community.

Gaps in the research literature

There are few papers identified that give focus to the voices of children and young people with experience in the justice system (See Table 8). The existing papers largely capture the voices of young males in juvenile detention, including Indigenous males. There is a need for more research exploring the experiences and views of females in juvenile justice facilities. It is also important for future research to include the voices of CALD children and young people, including refugees. This review suggests that the gaps in child and youth voice include the following topics:

The impact of detention on social networks and family relationships

The experience of living in a juvenile justice facility

Juvenile detention and the impact on sense of self and agency

Programs to reduce recidivism, including those designed to address violent behaviour, addiction, literacy, numeracy and life skills

Therapeutic services addressing trauma

The experiences of juveniles in adult facilities

Table 8. Australian child participatory research on juvenile justice from 2000 to 2018

Part 2. The extent to which the included research is participatory

All 207 papers identified were reviewed according to the Shier’s (Reference Shier, Berson, Berson and Gray2019) participation matrix. All of the papers involved children as research participants who provided data to adult researchers. This is not surprising, given that this was the baseline criteria for inclusion in the scoping review. Relatively few papers engaged with participatory methodologies across other phases of the research. Level of participation for each of the Shier’s research phases is summarised in Figure 4. In interpreting Figure 4, note the interrupted horizontal scale. The graphic cannot adequately visualise the fact that the role of children as data subjects (providers of data to adult researchers) exceeds all other kinds of involvement by a significant order of magnitude.

Fig. 4. Nature of participation across 207 papers.

Discussion and conclusion

The scoping review described in this paper demonstrates the interest across Australian service sectors in conducting child voice research and working to gather the perspectives of children and young people as this relates to their experiences as users of services. It is evident that there is room within the Australian context to more actively pursue a participatory child research agenda, and it is important that we continue to explore the many ways in which this agenda can be advanced. Academic self-awareness, or researcher ‘reflexivity’ (Shier, Reference Shier2016), is essential, as researchers consider how their own identity and presence are accounted for, and the extent to which formal academic conventions (such as the use of a third person narrative or the measures of academic success and track record) may obstruct a participatory approach.

Across the literature included in the scoping review, there were commonalities. For example, all sectors most commonly relied on interview and focus group methodologies. A stark commonality was the observation that there were very few published projects across all sectors that engaged with children and young people in the different phases of the research beyond data collection. Shier’s participation matrix (Reference Shier, Berson, Berson and Gray2019) proved to be a very useful tool in looking at the extent to which the Australian literature was participatory across all phases of the research process. This paper is the first to employ Shier’s recently published matrix as a tool for reviewing a body of literature. Only 7 of the 207 papers included in this scoping review reported engaging children in decisions about research questions and project design. This is likely to primarily be a reflection on the processes required for researchers to secure research funding, in which all design work must be presented in funding applications, and so the questions and design are set in stone before researchers have the resources to engage with research participants. Shier’s matrix is unique in that it includes advocacy as a final step in the research process. Shier argues that advocacy is essential both to research impact and to fulfilling researcher commitment to the participants. Only 3 of 207 papers reported on advocacy activities. It is possible that there were advocacy activities that were not reported. It is also likely that current funding schemes do not extend to supporting advocacy activities. There is an important cross-disciplinary discussion to be had on how participatory researchers can work within, or work to change, current funding and review processes so that participatory research methods can be supported, from project conceptualisation through to advocacy for policy impact.

This paper supports the importance of the cross-fertilisation of research ideas across sector areas. For example, education is the only field in which participatory research is most often conducted with children in the early years (61% of the education papers identified in this review). For all other sectors covered in this review, early childhood is the least likely age group to be represented in the research. It is not surprising that the education literature is also the strongest in terms of the range of creative methodological approaches, precisely because of the interest in engaging meaningfully with young children. The education literature, therefore, has much to offer researchers from other sectors as this relates to understanding how to conduct research with young children, and also in relation to the use of creative methodologies to support research participation. As a case in point, within the disability literature, there is a tendency for participatory research to focus on children with physical disabilities. Presumably, an influential factor in this focus is that it is easier to employ common qualitative approaches, such as interviews and focus groups, with groups of children who do not experience cognitive or sensory impairment. Understanding of more creative methodologies may open the way for the participation of children and young people for whom methodologies requiring verbal responses may not be appropriate. It should be noted that the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, as quoted at the start of this paper, guarantees the right to be heard to every child who is ‘capable of forming’ a view and does not restrict this right to those who are also capable of expressing their views in a standard, adult-approved way. The mental health literature was exemplary in engaging with diverse participant groups, as was research on housing and homelessness and community. These literatures could be drawn on to support other research across the sectors that seek to engage with vulnerable or marginalised populations.

This scoping review is limited by the time boundaries that we placed on our searches, along with restrictions on the number of databases searched. We also acknowledge that there is high-quality research conducted with children in Australia that has not been published in peer-reviewed journals and so has not been captured within this review. Nonetheless, this paper sketches the landscape of peer-reviewed participatory Australian research with children since 2000. Our hope is that this paper will serve as a catalyst for new discussions and new collaborations to continue to build the strength of child participation within the Australian research context. Future research will give focus to the nature of child participation within the grey literature and Australian policy documents and will examine the effectiveness of strategies that have been employed with the aim of meaningfully engaging children and young people in research.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of research assistants Lindy Walsh, Kim Miller and Emily Cheater.

Financial Support

This review was supported by a Macquarie University Collaborative grant awarded to Rebekah Grace and Kelly Baird.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cha.2019.32