Introduction

In July 2014, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples concluded that Canadian Aboriginal peoples face human rights problems of crisis proportions. 1 The consequences of this are evident every day in many of Canada’s emergency departments (EDs), yet the implications for ED patient care are not obvious. In a recent report, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) stated, “[I]f the mainstream healthcare system in Canada is to be effective in helping to improve the health of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis clients, it must provide culturally safe care.” 2 EDs across the country treat the most acute manifestations of Aboriginal health inequities, manifested through disproportionate burdens of addiction, mental illness, physical trauma, chronic diseases, and infectious diseases. However, concepts related to cultural safety remain nebulous to most emergency physicians. The purpose of this paper is to present background and principles relevant to the practice of cultural safety in the ED.

Urban Aboriginal Peoples’ Health in Canada

Cultural safety in health care for Aboriginal peoples refers to practices rooted in a basic understanding of Aboriginal peoples’ beliefs and history and a process of self-reflection regarding the power differential existing between provider and patient that may affect the process of care and healing. 3 The health inequities faced by many Aboriginal peoples today first took root in striking social, economic, and cultural trauma experienced throughout our collective history. The history of “residential schools,” which spanned over one hundred years and lasted until 1996, is perhaps the most recognized example. 1 A particularly distressing time was during “the Sixties Scoop,” (1960–1980) during which time over 11,000 Aboriginal children were forced to leave their homes, 4 placed in the child welfare system, and made to attend culturally foreign institutions with the stated goal of erasing their culture and family tiesReference Johnston 5 . Though the last residential school closed in 1996, the disruption of Aboriginal families persists, and Aboriginal children continue to be significantly more likely to be in foster care compared to non-Aboriginal children. 6 Though much positive work has been done to repair the relationship with Aboriginal peoples in Canada, 1 the legacy of residential schools and colonial policies created deep intergenerational traumas and suspicion, the consequences of which remain visible today in many EDs 1 , Reference Brascoupé and Waters 7 , Reference Felitti, Anda and Nordenberg 8 . Furthermore, systemic race-based policies such as the federal Indian Act (which externally defines who is “Indian” and who is not), and marked inequities in the distribution of health and social resources continue to harm Aboriginal individuals and communities in Canada and undermine efforts of communities to govern themselves.

It is well documented that Aboriginal peoples in Canada suffer much higher rates of infectious diseases,Reference Morrisseau 9 , 10 chronic disease,Reference Adelson 11 , Reference Lix, Bruce and Sarkar 12 and mental illness, 13 all contributing to a significantly lower life expectancyReference Adelson 11 , Reference Lix, Bruce and Sarkar 12 , Reference Tjepkema, Wilkins and Senécal 14 , Reference Young 15 . Evidence suggests health inequities are exacerbated among urban populations.Reference Tjepkema, Wilkins and Senécal 14 , Reference Shah and Ramji 16 , 17 Today, over 60% of Aboriginal peoples in Ontario reside in urban areas. 18 While some have benefited from the rural to urban transition, 19 , Reference McCaskill, FitzMaurice and Cidro 20 many others have experienced marginalization, poverty, and housing insecurity 18 , Reference Garner, Carrière and Sanmartin 21 – Reference Shah, Klair and Reeves 23 . A recent study of Aboriginal peoples living in downtown Toronto found a mean age at death of 37 years, and linked most of these premature deaths to homelessness, physical violence, and substance use, exacerbated by poorly treated chronic conditions.Reference Shah, Klair and Reeves 23

Urban Aboriginal Peoples and the ED

Urban Aboriginal peoples are more likely to access ED care than the general population. A recent study of First Nations people living in Hamilton, Ontario, found that over 10% had more than six ED visits during the preceding two years, compared to 1.6% of overall Hamilton residents.Reference Firestone, Smylie and Maracle 22 Yet, 44% of First Nations people surveyed rated the quality of their ED care as fair or poor.Reference Smylie, Firestone and Cochran 24 A recent qualitative study in Vancouver found that during ED visits, Aboriginal patients often feel judged for being Aboriginal and living in poverty or presumed to be expressing illegitimate pain.Reference Browne, Smye and Rodney 25

In 2012, the Health Council of Canada held discussion groups with Aboriginal patients and their care providers who reported experiences of racism or stereotyping affecting the quality of ED care. One participant reported witnessing: “An Aboriginal man… was beaten and bloodied… he was not allowed to lie on a bed. When a physician asked why the patient was not lying down, the nurse explained that the man was dirty, and would just return to the street… to engage in the same risky behaviours that had landed him in emergency. In fact, the patient was employed, owned a home, and had been attacked on his way home from work.” Other participants reported instances of missed or late diagnosis (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis) arising from assumptions of addiction and intoxication. 26 As frontline providers, ED health care providers are well-situated to intervene on inequities faced by Aboriginal patients. In the chaotic and risk-prone environment of the ED, cultural safety can help patients, their communities, and their health care providers.

What is Cultural Safety?

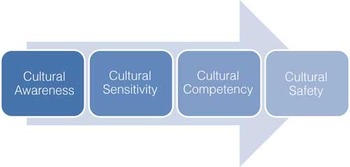

Cultural safety is usually seen as a continuum of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours that begins with cultural awareness.Reference Ramsden 27 (Figure 1.) Culturally safe care involves understanding and acknowledging the power differential existing between provider and patient,Reference Brascoupé and Waters 7 , 28 and adjusting behaviour and services to empower and better meet patients’ needsReference Peiris, Brown and Cass 29 . In a recent analysis, Kumagai and Lypson stated that in order to adequately meet these needs, physicians must progress beyond cultural competency and develop a “critical consciousness” that views patients within a social, cultural and historical context, regardless of income, gender, or ethnicity.Reference Kumagai and Lypson 30 The RCPSC wrote that a culturally safe provider “practices critical thinking and self-reflection,” and, in specific regard to Aboriginal peoples, “understands the unique historical legacies and intergenerational traumas affecting [their] health and fosters an understanding of [their] health values.” 3 This process of recognizing our own biases minimizes the risk of cognitive errors that can affect diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. Critical self-reflection helps identify stereotypes that ultimately result in unsafe care.

Figure 1 Continuum of Cultural Safety 38 Cultural safety can be seen as a continuum of knowledge, attitudes and behaviours that begins with cultural awareness.

The value and relevance of cultural safety principles extends beyond Aboriginal peoples. Cultural safety principles can be applied to the challenges faced by many groups in Canada whose health status and health care access has the potential to be compromised by historical and social context, discrimination, material deprivation, or power imbalances. Past experiences of alienation, perceived inequality, and maltreatment require sensitivity and compassion from health care providers. Trust and relationships are integral to the practice of cultural safety, and can be enhanced by the use of a language interpreter, a cultural broker, or by obtaining greater knowledge of the patient’s culture or values.

Accessing health care involves potential harms as well as potential benefits. Iatrogenic injuries and nosocomial infections have been shown to harm thousands of patients every year in Canada.Reference Baker, Norton and Flintoft 31 Similarly, health care can carry the risk of emotional and psychological harm. While medical care brings comfort for many, some patients receive care that makes them feel judged, disempowered, or unimportant. As a result, old emotional wounds may unexpectedly arise—particularly with survivors of psychological trauma—as a consequence of culturally unsafe care.

Aboriginal Patients and a Culturally Safe ED

Cultural safety matters in the ED. Aboriginal peoples in Canada currently face a national health crisis. Cultural safety allows providers to create respectful alliances with patients to improve their health. 2 , Reference Peiris, Brown and Cass 29 A lack of cultural safety can reduce effective access to health services. 28 It can also alienate patients, reduce adherence to treatment, exacerbate psychological trauma, and leave patients with a diminished sense of autonomy and empowerment (a factor known to be associated with care avoidance).Reference Browne, Smye and Rodney 25 , 26 Drawing on previous work in Canada and New Zealand, 32 - Reference Allan and Smylie 34 we propose four guiding principles and resulting possible actions to address cultural safety in ED care (Table 1).

Table 1 Proposed Principles to Address Cultural Safety in ED Care

Cultural safety is relevant to every person involved in ED patient care, from security personnel to nurses and physicians. The RCPSC emphasizes that cultural safety must be an important component of physicians’ professional development and practice. 3 The RCPSC’s CanMEDS framework for post-graduate medical education has been very influential in shaping the development of specialist emergency medicine (EM) training programs over the past decade, unambiguously supporting critical thinking and self-reflective skills that promote cultural safety. The framework now specifically states that “the culturally competent physician embraces Indigenous knowledge,” and “Indigenous health is an integral component of medical research, education, training and practice.” 35

Recent encouraging initiatives have advanced cultural safety in Canadian health care. For example, a First Nations Health Authority was recently created in British Columbia (BC) as part of a unique governance structure intended to enable First Nations people to take charge of the planning, management, delivery and funding of health programs. 36 Another BC initiative recently created an online program on cultural competency for health care providers who work with Aboriginal patients. 37

Emergency physicians are in a unique vantage point to witness the consequences of health disparities within our society. As a community, we have previously shown a great capacity for introspection and evolution in responding to health-related social issues, from the AIDS epidemic to intimate partner violence. At the same time, Aboriginal communities have demonstrated tremendous resilience in the face of economic and social obstacles, and organized themselves to bolster self-determination and well-being. In many communities across Canada, EDs represent a crucial point of access to care for Aboriginal patients. As a result, Canadian emergency physicians are ideally positioned to lead and take on the challenges of improving the cultural safety of ED care.

Competing Interests: Dr. Janet Smylie is supported by a Canadian Institute for Health Research Applied Public Health Research Chair. The authors do not have any other financial or other conflicts of interest to declare.