The effects of conspiracy theories (CTs) on health were scrutinized by many studies, particularly with respect to COVID-19. The validity of surveys measuring CTs was often taken at face value, although survey answers do not always reflect the true beliefs of respondents.Reference Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski1 GrahamReference Graham2 revealed that respondents denying the existence of global warming in a survey were more likely to answer that global warming exists when asked again. Across different topics, endorsement of CTs was negatively related to temporal stability of answers (TS): the consistency of repeated answers of the same respondent. This study conceptually replicates the Graham’s findings with a popular survey measuring COVID-19-related CTs and explores their potential causes.

TS may be reduced in those who endorse CTs (“conspirators”) compared to those who do not (“skeptics”) for 3 reasons. First, novel information may lead the “conspirators” to re-evaluate their opinions (“re-evaluation hypothesis”). Second, “conspirators’” answers may be random or erroneous. When asked repeatedly, “conspirators” may provide more accurate answers or different guesses. The “conspirators” responses would have lower TS than “skeptics’” responses, provided most respondents do not endorse CTs due to regression to mean and middle (“regression hypothesis”).Reference Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski1 Third, “conspirators’” opinions may reflect respondents’ momentary mindsets rather than stable beliefs (“mindset hypothesis”).

Method

Procedures and Participants

Mimicking our previous studies,Reference Pisl, Volavka and Chvojkova3, Reference Pisl, Volavka, Chvojkova and Cechova4 we presented a set of 6 items addressing the beliefs that COVID-19 was created for evil purposes (CC-CT) and that COVID-19 is a hoax (CH-CT)Reference Imhoff and Lamberty5 to 179 students of the third year of general medicine (115 females). The items were presented 3 times: in March 2022 with 11-point Likertian options (L1), few minutes later with a request to estimate the percentual probability of the statement being correct (N1), and 2 months later with Likertian options (L2). The study was approved by Ethical Committee of University Hospital Pilsen and Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University (79/2022).

Analysis

The analysis was conducted separately for CC-CT and CH-CT.

Paired t tests comparing L1 and L2 scores were used to rule out the “re-evaluation hypothesis.” Pearson correlation was used to calculate TS (between L1 and L2) and to compare the inconsistency of answers (absolute difference between L1 and L2) to conspiracy endorsement (L1).

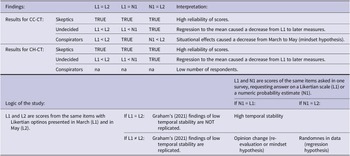

To test the regression and mindset hypotheses, the sample was split by the L1 scores into groups of “skeptics,” “undecided,” and “conspirators.” In each group, rmANOVA followed by t tests was used to compare the L1, N1, and L2 scores. The regression hypothesis would be supported if L1 > N1 = L2 in conspirators, because regression to the mean/middle would happen already from L1 to N1. The mindset hypothesis would be supported if L1 = N1 > L2 in conspirators, because mindset would be the same in L1 and N1 but different 2 months later (L2).

Results

CC-CT: The L1 and L2 did not differ (P = 0.28); TS was poor (r = .67); inconsistency correlated with L1 (r = .21; P < 0.01). Of 18 participants endorsing the CC-CT in March (L1), 8 endorsed it in May.

When split into groups, in skeptics (n = 146), L1, N1, and L2 did not differ (F(1.87,266) = 1.87; P = 0.16). Those undecided shown decrease (n = 27; F(2,52) = 10.44; P < 0.05) from L1 to N1 (t(26) = 2.24; P < 0.05) and L2 (t(26) = 2.39; P < 0.05); N1 and L2 did not differ (P = 0.49)). The conspirators’ (n = 10) scores differed (F(2,18) = 10.44; P < 0.001) from L1 to L2 (t(9) = 3.61; P < 0.01) and from N1 to L2 (t(9) = 3.59; P < 0.01); L1 and N1 did not differ (P = 0.41; see Figure 1 and Table 1 for summary).

Figure 1. Mean CC-CT scores in groups identified by the initial (L1) answers; * for P < 0.05, ** for P < 0.01.

Table 1. Summary of the key findings and their explanation

Note: To test the “mindset” and “regression” hypothesis, participants were split into groups of conspirators, undecided, and skeptics by their first (L1) score.

CH-CT: L1 and L2 did not differ (P = 0.75); TS was poor (r = .57); inconsistency was correlated with L1 (r = .44; P < 0.001). Of 6 participants endorsing CH-CT in March, 1 endorsed it in May.

The skeptics’ (n = 167) answers did not differ between L1, N1, and L2 (F(2,324) = 1.78; P = 0.17). Decrease was observed in those undecided (n = 13; F(2,24) = 4.75; P < 0.05) from L1 to N1 (t(12) = 2.29; P < 0.05) and to L2 (t(12) = 2.44; P < 0.05); N1 and L2 did not differ (P = 0.34; Table 1). Not conducted for conspirators due to inadequate sample (n = 3).

Discussion

The TS was suboptimal (r < .7) and negatively correlated with endorsement of CTs. The mean endorsement of CTs has not changed from March to May 2022, but the majority of those endorsing a CT in March did not endorse the same CT in May. The “conspirators’” answers were stable when responding in March on a different scale, indicating their answers were not random (not supporting the “regression hypothesis”). Yet, they differed 2 months later, supporting the “mindset hypothesis” that the endorsement of CTs in March reflected momentary mental processes rather than stable beliefs. Thus, the endorsement of CTs may have been increased by momentary judgements and motivations Reference Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski1 or situational factors, such as affect or stress.

Endorsing CTs in a survey have not reflected stable beliefs of respondents in this study. Instability of the answers of those who endorse CTs in survey may inflate the estimates of the prevalence of CTs, in addition to other biases.Reference Clifford, Kim and Sullivan6 Furthermore, the situational mindset may simultaneously affect endorsement of CTs and other survey-based variables, resulting in spurious correlations.Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Lee7

These results are consistent with studies revealing lowReference Graham2 rather than highReference Williams, Ling and Kerr8 TS of survey-based measures of CTs. This study is limited by specific sample and small number of “conspirators.” The proportion of unstable answers of all pro-conspiracy answers may be higher in this study due to low prevalence of stable pro-conspiracy beliefs in this medically educated sample. Yet, many quantitative studies on COVID-19-related CTs, including ours,Reference Pisl, Volavka and Chvojkova3, Reference Pisl, Volavka, Chvojkova and Cechova4 used the same or similar items and samples. Their results should therefore be taken as potentially biased, until the instability of pro-conspiracy answers about COVID-19 is reliably quantified.

Author contribution

Conceptualization – VP, JVo, GK, JVe; Data curation – VP; Formal Analysis – VP; Funding acquisition – Jve; Investigation – VP, GK, JVe; Methodology – VP, JVo, JVe; Project administration – VP, JVe; Supervision – JVo, JVe; Writing – original draft – VP; Writing – review & editing – VP, JVo, GK, JVe.

Funding

This work is supported by the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, under the grant number VJ01010116.

Competing interest

The authors report they have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical standard

The research was approved by the Ethical Committee of University Hospital Pilsen and Faculty of Medicine in Pilsen, Charles University, nr. 79/2022.