What is the law? Is it the answer that courts have already provided in response to a question, or is it the answer that courts would provide to the same question if it was put to them again? The question cuts to the heart of debates in the philosophy of law. But it also makes one thing particularly clear: the law is not static. Indeed, the law is always in flux, constantly changing and evolving, in response to both underlying social and economic forces and the social dynamics of the legal profession and legal institutions. It is impossible to fully understand the role of law and legal institutions in society without understanding the relationships between legal and social change and the ways in which legal institutions influence the dynamics.

This article attempts to further our understanding of legal innovations through an empirical study of important changes in American employment law in the last quarter of the twentieth century. By the middle of the twentieth century, the employment-at-will rule had become the most distinguishing feature of American employment law (Reference MorrissMorriss 1994). Under the employment-at-will rule an employer could terminate an employee without notice and for any reason, good or bad (Reference MorrissMorriss 1994). As the United States entered the 1960s this gradually began to change. Some courts began to recognize limited exceptions to the employment-at-will rule. Soon enough, a movement was afoot and by the 1990s most states had adopted at least one of three basic exceptions to the employment-at-will rule (Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006).

Today, these exceptions to the employment-at-will rule define the contours of modern wrongful-discharge law. Under the wrongful-discharge laws of most states today, for instance, an employer cannot terminate an employee without notice or reason if the employer has stated termination policies and grievance procedures in its personnel manuals or employee handbooks that are inconsistent with employment-at-will (Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006). Similarly, an employer cannot terminate an employee for absences due to the fulfillment of jury duty obligations or the employee's decision to file worker's compensation claims, or for any other reasons that conflict with important public policies (Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006). Wrongful-discharge laws have thus brought about significant reforms in the American labor market.

This article evaluates the factors that have influenced the diffusion of the wrongful-discharge laws across the states.Footnote 1 A number of other studies in the social sciences and law have examined the diffusion of other new laws across the states. Some of these have focused on the diffusion of new state legislation (Reference Fishback and KantorFishback & Kantor 1998; Reference MooneyMooney 2001; Reference MahoneyMahoney 2003), while others have examined the diffusion of new legal precedents (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985; Reference SiskSisk et al. 1998), but only two have directly addressed the employment-at-will rule. In one study, Reference MorrissMorriss (1994) examined the diffusion of the employment-at-will rule during the late nineteenth century, and in another Reference KruegerKrueger (1991) examined the diffusion of unjust-dismissal legislation proposals across the states. No one has yet examined the diffusion of the wrongful-discharge laws across the states.

This study thus attempts to evaluate which factors have influenced courts' decisions to adopt wrongful-discharge laws. One obvious possibility is that legal precedents from other jurisdictions may have influenced courts' adoption decisions. This raises questions about how to evaluate the persuasiveness of legal opinions from other jurisdictions. Other scholars have attempted to do so using citation counts (Reference SiskSisk et al. 1998). While this approach is interesting, it may be fallible. Reference WalshWalsh (1997), for instance, used wrongful-discharge cases to study the role of legal citations in court opinions. He found evidence that legal citations in wrongful-discharge cases reflected both meaningful inter-court influences and courts' legitimizations of their decisions. This suggests that citation studies may have important limitations as a method for evaluating the persuasiveness of legal precedents and that other approaches may also provide useful insights.

In contrast to the citation studies, this article uses social network theory to help frame the empirical analysis. It conceives of state courts as actors within social networks. Thus, instead of using citation counts, it assumes that the relative persuasiveness of decisions by other courts depends on the relationship between two courts within the social network. One advantage of this approach is that it allows us to assess whether the structure of American legal institutions may have had an influence on the diffusion of wrongful-discharge laws. It also provides a very flexible way of evaluating how patterns of influence may operate within the American legal system. By framing the empirical analysis as a diffusion process within a social network, for instance, we are able to assess which courts have been most influential in the diffusion process. We are also able to compare the relative importance of social network variables in the diffusion process to economic and political variables.

The results are surprising and quite striking. Other diffusion studies have often assumed that geography dominates in diffusion processes (Reference Fishback and KantorFishback & Kantor 1998; Reference MahoneyMahoney 2003). Based on these other studies, therefore, we expected that decisions to adopt wrongful-discharge laws by courts in neighboring states would dominate decisions to adopt by courts that belonged to other reference groups. As it turns out, however, precedents by other courts within the same federal circuit region were generally more influential in the diffusion of the wrongful-discharge laws than precedents by courts in neighboring states or by courts within the same censusFootnote 2 or West legal reporting region,Footnote 3 even though the precedents were on matters of state law rather than federal law and the decisions were usually made by state courts rather than federal courts. Thus, legal institutions rather than geography appeared to play the most important role in the diffusion process. Moreover, because some studies have found that wrongful-discharge laws have had adverse economic consequences (Reference Bird and KnopfBird & Knopf forthcoming; Reference Dertouzos and KarolyDertouzos & Karoly 1992; Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006), we also expected to find that economic and political variables would play an important role in the diffusion process. This proved not to be the case. There is some limited evidence that political variables may have been a factor, but economic variables did not appear to be important at all. Thus, social network effects appear to have been far more important in the diffusion process than economic or political variables.

The next section of the article offers an overview of wrongful discharge laws as well as the application of social network analysis to the study of the American legal system. The second section describes the data and the variables used in the empirical analysis, and the third section explains the empirical methods. The fourth section presents the results, and the final section offers some conclusions and suggestions for further research.

Overview

The Employment-At-Will Rule and the Wrongful-Discharge Exceptions

The employment-at-will rule was described in a classic nineteenth-century case as allowing employers to “discharge or retain employees at-will for good cause or for no cause or even for bad cause without thereby being guilty of an unlawful act per se” (Payne v. Western & Atl. R.R., 81 Tenn. 507, 518 [1884], overruled on other grounds, Hutton v. Watters, 179 S.W. 134 [Tenn. 1915]). The court went on to note that it was a right that employees “may exercise in the same way, to the same extent, for the same cause or want of cause as the employer …” (Payne v. Western & Atl. R.R., 81 Tenn. 507, 518 [1884], overruled on other grounds, Hutton v. Watters, 179 S.W. 134 [Tenn. 1915]). Although employment-at-will became the generally accepted default rule for employment contracts in all states by the early twentieth century, it emerged from the case law only in the late nineteenth century (Reference MorrissMorriss 1994). By the middle of the twentieth century, however, few cases that challenged the rule were even taken to court (Reference MorrissMorriss 1994). Ironically, the history of American employment law since the middle of the twentieth century has been dominated by the emergence and diffusion of various exceptions to the rule and a proliferation of wrongful-discharge cases.

The employment-at-will rule was first modified by a California court in Petermann v. International Brotherhood of Teamsters in 1959. Soon after that, Reference BladesBlades (1967) published an influential article criticizing the rule; several other commentators subsequently also criticized the rule (Reference MorrissMorriss 1994). Between the late 1970s and the 1990s, the rule was successively modified throughout most states by court decisions that adopted one or more of three basic exceptions to the employment-at-will rule.Footnote 4 For convenience, these have been described in the literature as the implied contract exception, the public policy exception, and the good faith exception (e.g., Reference MorrissMorriss 1994; Reference MilesMiles 2000; Reference AutorAutor et al. 2004). Each of the exceptions is rooted in a fundamental legal doctrine that justifies a departure from the employment-at-will rule.

Under the implied contract doctrine, courts infer that the parties have implicitly contracted around the employment-at-will rule, usually through the assurances implicit in the employer's procedures and practices. These assurances may be oral, but they are more commonly included in a personnel manual or employees' handbook or other written information provided by the employer to the employee (Reference MilesMiles 2000; Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006). Although many employers now include disclaimers of the implied contract doctrine in their personnel manuals and employees' handbooks, some courts have held that these are ineffective (Reference MilesMiles 2000). The implied contract doctrine was not widely adopted until the 1980s. In 1980, the Michigan Supreme Court adopted it in a highly publicized case; California followed a year later, and by 1986, courts in 25 other states had adopted the exception. It has now been adopted by 41 states (Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006).

Under the public policy doctrine, courts hold that an employee's discharge is wrongful if it violates well-established principles of public policy (Reference MilesMiles 2000; Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006). The doctrine normally applies only when an employee is terminated for refusing to commit an illegal act, such as price-fixing or perjury; for missing work to perform a legal duty, such as jury duty; for exercising a legal right, such as filing a workmen's compensation claim; or for disclosing the employer's wrongdoing. Although the public policy doctrine was first adopted by California in 1959, it did not diffuse widely until the 1980s. Between 1979 and 1994, 34 states adopted the exception, and it has now been adopted by 43 states (Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006).

Under the good faith doctrine, courts hold that an employee's discharge wisas wrongful if it serves to prevent the employee from realizing his or her contract rights—for instance, because the employee is denied compensation due for commission sales, or because the employee was discharged just before his or her pension was about to vest (Reference MilesMiles 2000; Reference AutorAutor et al. 2006). Although California and a few other states adopted the good faith doctrine in the 1970s and 1980s, it has not diffused as widely as the other exceptions. Only 11 states currently recognize the good faith exception.

Social Network Theory and the Diffusion Process

This study attempts to assess how and why the three exceptions to the employment-at-will diffused across most of the American states. In an early study Reference WalkerWalker (1969) framed this type of research problem as a sociological phenomenon and drew insights from the sociological literature on the diffusion of innovations (for an overview, see Reference RogersRogers 1995).Footnote 5 Many subsequent studies have also adopted this approach (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985; Reference MooneyMooney 2001; Reference Boehmke and WitmerBoehmke & Witmer 2004). Indeed, there is a natural sense in which new legislation and new legal precedents are merely innovations like any others, and legislatures' or courts' decisions to adopt them bear an analogy to the decisions that other actors make about whether to adopt new production techniques, professional practices, or modes of behavior. This study therefore also draws on that approach.

In contrast to the previous studies, however, this article focuses on how the social structure of legal institutions has influenced the diffusion process. To that end, it assumes that the social structure of the legal system influences judicial outcomes and attempts to draw inferences about the pattern of social influence between judicial actors.Footnote 6 From this perspective, the American legal system is a social network, and the decisions of a court in any one state depend to some extent on the relative influence or persuasiveness of precedents by courts in other states.Footnote 7 The relative influence of precedents by other courts depends on the relationship between the two courts in the social network. Decisions by courts within the same reference group (members of a subgroup that relate more closely to one another than to others outside the group) will be more persuasive than decisions by courts that are not within the reference group.Footnote 8

Of course, the American legal system is somewhat more complicated than that, and so precedents operate on at least three levels. Cases must first of all “bubble up” to the courts before the courts can have a chance to hold on any new legal questions they raise. In the American legal system parties are responsible for asserting their private legal rights, and so at the first stage in the legal process, a precedent by a court in another state adopting an exception to the employment-at-will rule could encourage discharged employees to seek a remedy for wrongful discharge based on the same exception. They would normally then take their case to an attorney. At this second stage in the legal process, court precedents adopting an exception to employment-at-will in other states might encourage the discharged employee's attorney(s) to accept the case and use the exception as the basis for a wrongful-discharge complaint. At that point, the question of whether the exception applies in the discharged employee's state would come before a court, and the court would be required to make a decision one way or another. Precedents in other states could influence the court's decision at this third stage in the legal process.

The social structure of the legal system could be important at all three stages in the process. First of all, a discharged employee may be more likely to feel he or she has grounds for a lawsuit against an employer if he or she hears about a successful wrongful discharge case from another jurisdiction, and the employee may be more likely to hear about such a case if it is from a neighboring state or a state within the same region of the country than if it is from some distant and dissimilar state. Second, any attorney to whom the employee initially takes grievances may be more inclined to take the case in reliance on a precedent if the attorney feels it will be a persuasive one that will allow the client's complaint to survive summary judgment. An attorney might feel that a precedent from a court within the same federal circuit region or the same geographical region will be more persuasive than others. Finally, the court that hears the case may actually be more persuaded by some precedents than others; courts may be more strongly influenced by precedents within the same federal circuit area or the same geographical region of the country than by courts in states that belong to some other reference group, whatever that might be.

One of the difficulties in using social network theory to study the diffusion of legal precedents is in identifying the relevant reference groups. What criteria determine whether another court's precedent will be persuasive? Previous studies of legal citations in courts' opinions suggest that the persuasiveness of a precedent may depend on criteria such as membership in the same legal reporting district, geographical proximity, and regional culture (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985). Other studies suggest that the federal circuit regions are an important reference group for federal judges and that federal judges frequently attend the meetings of the state bar associations within their circuit districts (Reference CarpCarp 1972; Reference Stidham and CarpStidham & Carp 1988). This suggests that the federal circuit regions may also define an important reference group for attorneys and state judges.

This study therefore identified four reference groups and tested and compared the influence of precedents by other courts within these groups in the diffusion of the new employment doctrines. The four reference groups were (1) neighboring states, (2) states within the same federal circuit region, (3) states within the same West reporting region, and (4) states within the same census region. The objective in the first place was to determine whether precedents within any of these reference groups were at all persuasive on their own, and in the second place to distinguish whether precedents in any one of the reference groups were generally any more influential than precedents in the others.Footnote 9

Of course, each of the three exceptions to the employment-at-will rule is legally distinct from the others. Nonetheless, the adoption of one of the exceptions by the courts within a state may have influenced their decision whether to adopt one of the other exceptions. For instance, a court's decision to adopt the implied contract exception may have subsequently influenced that court or another court within that state to have adopted the public policy exception. Alternatively, a court's decision to adopt the good faith exception may have subsequently influenced it or another court within that state to have adopted the implied contract exception. Therefore, this study also attempts to determine whether prior adoptions of other exceptions influenced the diffusion of each of the employment doctrines.

Economic and political factors may also have been important. Indeed, most of the research on the employment doctrines has focused on their economic consequences. Since these doctrines should all, in theory at least, increase the costs to employers from wrongfully discharging employees, they might also inhibit employers from hiring workers in the first place. Thus, Reference Dertouzos and KarolyDertouzos and Karoly (1992), Reference MilesMiles (2000), and Reference AutorAutor et al. (2006) have studied and debated the labor market responses to the diffusion of the new employment laws. Of course, if a court anticipated that a new legal holding adopting one of the employment doctrines might have adverse consequences for labor markets, that might influence the court's decision. For instance, a court might have been less likely to adopt an exception to the employment-at-will rule if the state unemployment rate was already high. Or it might have been more likely to adopt an exception if the proportion of the state's labor force that was unionized was high (under the reasonable assumption that the exception would have less impact on the unionized sector of the labor market).

The absolute size of the labor market could also have influenced the likelihood of adoption. The likelihood that a case might come up requiring a court to make a decision about whether to adopt one of the new employment doctrines probably depended in large part on the size of the labor market. Other things remaining equal, the likelihood that a plaintiff might have asserted a cause of action based on one of the new employment doctrines should have depended on the number of contentious employment terminations, and the number of contentious employment terminations should have depended on the total number of people employed.

If the wrongful-discharge laws had important economic consequences, there is also a possibility that courts' adoption decisions may have been influenced by larger political and ideological trends. One might expect, for instance, that courts in politically conservative states during politically conservative periods would be less inclined to adopt wrongful-discharge laws that they expected to have adverse economic consequences. Conversely, one might expect that courts in politically liberal states during politically liberal periods would be far more inclined to adopt wrongful-discharge laws in spite of any expected adverse economic consequences.

The Data

The Employment Doctrines

The dates on which each of the exceptions to the employment-at-will rule were adopted as the law in any state were obtained from the study by Reference AutorAutor et al. (2006).Footnote 10 Since that study spanned the years from 1978 to 1999 and included Alaska and Hawaii as well as all contiguous states, the full sample includes 1,100 observations on each variable. Since each exception was adopted in a few states prior to 1978, there is a small amount of left-censoring in the data. It was not possible to extend the entire dataset far enough back to eliminate the left-censoring, but estimations of a slightly modified version of the basic model indicate that the main results herein are robust to a correction for left-censoring bias.Footnote 11

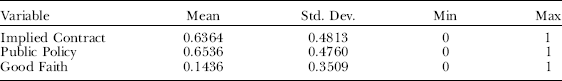

Summary statistics on the three employment doctrine variables are presented in Table 1. Since the implied contract and public policy exceptions were much more widely adopted over the sample period than the good faith exception, the means of the implied contract and public policy binary variables are significantly greater than the mean of the good faith binary variable. As with all binary variables, the standard deviations provide little information. Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative distributions of each of the three exceptions across the sample period. The cumulative distributions of both the implied contract and public policy exceptions conform to the S-curve pattern common for most innovations. The cumulative distribution of the good faith exception is much flatter; however, as Figure 1 indicates, the good faith exception was much less widely adopted than the other two.

Table 1. Summary Statistics for the Employment Doctrine Variables—Means and Standard Deviations

Figure 1. The Cumulative Adoptions of the Wrongful-Discharge Laws, 1978–1999

The “Social Network” or “Contagion” Variables

A state court's decisions (or a federal court's decisions on questions of state law) have no binding authority over other states' courts, but they may well have significant persuasive authority. They may also encourage litigants in other states to invoke new legal doctrines. The implied contract, public policy, and good faith binary variables were therefore used to construct a number of “social network” or “contagion”Footnote 12 variables. These provided a way of evaluating the precedential effects of prior adoptions of the doctrines by courts in other states. Network variables were constructed to isolate and compare the effects of precedents by courts in (1) neighboring states, (2) the same federal circuit region, (3) the same West reporting region, and (4) the same census region.Footnote 13 The network variables were defined as the proportion of states within the reference group that had adopted the employment doctrine by the end of the previous year.Footnote 14 It is worth emphasizing that although two of these network variables (the ones defined for the census regions and neighboring states) are strictly geographic in nature, the other two (the ones defined for the federal circuit and West reporting regions) primarily reflect the social structure of American legal institutions.

For each of the employment doctrines, this implied the following network variables: a neighboring state network variable equal to the proportion of neighboring (contiguous) states that had adopted the employment doctrine by the end of the previous year; a federal circuit region network variable equal to the proportion of states within the same federal circuit region that had adopted the employment doctrine by the end of the previous year; a West reporting region network variable equal to the proportion of states within the same West reporting region that had adopted the employment doctrine by the end of the previous year; and a census region network variable equal to the proportion of states within the same census region that had adopted the employment doctrine by the end of the previous year.Footnote 15

It is often the case that a state belongs to two or more of the reference groups for another state. For instance, Oregon is a neighbor of California, as well as a member of the same federal circuit region, the same West reporting region, and even the same census region. A precedent in Oregon, therefore, could influence courts in California through Oregon's membership in any or all of these reference groups. It is not surprising, therefore, that the network variables defined for each of the employment doctrines generally exhibited a high degree of correlation.Footnote 16 Indeed, the correlation coefficients for the implied contract network variables were all more than 0.70. The correlation coefficients for the public policy network variables were a bit smaller. The correlation coefficients for the good faith network variables were the smallest: they ranged from 0.43 to almost 0.68. One would naturally expect that these large correlations should make it difficult to distinguish between the effects of precedents within the various reference groups. This made some of the results particularly striking.

Economic Variables

To test whether courts may have been responsive to labor market conditions in deciding whether to adopt one of the new doctrines, economic variables were added to the dataset. These included the unemployment rate, defined as the state's average annual unemployment rate expressed as a percentage of the total labor force,Footnote 17 and the percentage of the state's labor force that are union members, defined as the percentage of the state's nonagricultural labor force that belonged to a union in each year as calculated by Reference HirschHirsch and colleagues (2001).Footnote 18 The size of the state's labor force was also added to the dataset to account for the likelihood of wrongful-discharge cases making their way into the courts in the first place.Footnote 19

Political Variables

A state's political culture may have influenced its courts' propensity to adopt one of the new employment doctrines directly, through the selection of state court judges, or indirectly, through the social context in which the judges made their decisions. Two types of political variables were thus added to the dataset. Eight binary variables based on Elazar's typology of political subcultures (1984) were added to the dataset to control for differences in states' political cultures. Reference ElazarElazar (1984) distinguished three dominant types of political cultures: moralist, individualist, and traditionalist. A moralist political culture views politics as the pursuit of the public interest and has little tolerance for corruption. An individualist political culture emphasizes the virtues of a free marketplace, a limited role for government, and skepticism of politicians. A traditionalist political culture values the status quo and tolerates the concentration of political power. Elazar elaborated on his typology by recognizing that a state might have one dominant culture in conjunction with a strong strain of another. He thus identified eight types of regional political subcultures.

In addition, two variables based on Erikson and colleagues' compilation of the CBS/New York Times annual polls of state respondents' party and ideological identifications were added to the dataset to control for changes in public opinion over the sample period (Reference Erikson and CohenErikson et al. 2006). These two variables were the percentage of a state's respondents who identified themselves as Republican in the CBS/New York Times polls and the percentage who identified themselves as liberal. Since the Erikson and colleagues data did not include Alaska and Hawaii, observations for these states had to be dropped in most of the regressions.

Empirical Method

This article uses hazard methods to evaluate which, if any, of the network variables most strongly influenced the diffusion of the three exceptions to the employment-at-will rule. There are two basic approaches to hazard analysis: one assumes that the data are generated in continuous time, and the other assumes that they are generated at discrete intervals. The data for this study were measured at discrete intervals, so this article reports the results of discrete time hazard estimations using a complementary log-log specification.Footnote 20 The complementary log-log model provides estimates that are the discrete time analog to the Cox regression model (Reference AllisonAllison 1982; Reference JenkinsJenkins 1995). If binary variables for each time interval are included in the regressions, then each time interval can contribute to the intercept of the model separately. This is tantamount to allowing the baseline hazard rate to vary across each interval.

The basic strategy was to try to identify robust empirical results.Footnote 21 Thus, all 10 political variables were included in most of the regressions even though they probably had overlapping effects. The point was to try to control for any political influences rather than isolate the influence of particular political variables. Moreover, binary variables for each time interval were included in all the regressions so that the baseline hazard rate could vary across years. Finally, in addition to the results reported here, many other regressions were run to determine whether the results were robust to the way in which the network variables were defined, whether continuous- or discrete-time methods were employed, which explanatory variables were included in the model, and whether the main findings could have been attributable to any left-censoring bias.Footnote 22 Not all of the results are presented here, but none of the results that have been omitted contradict any of the conclusions.Footnote 23

Results

The Implied Contract Exception

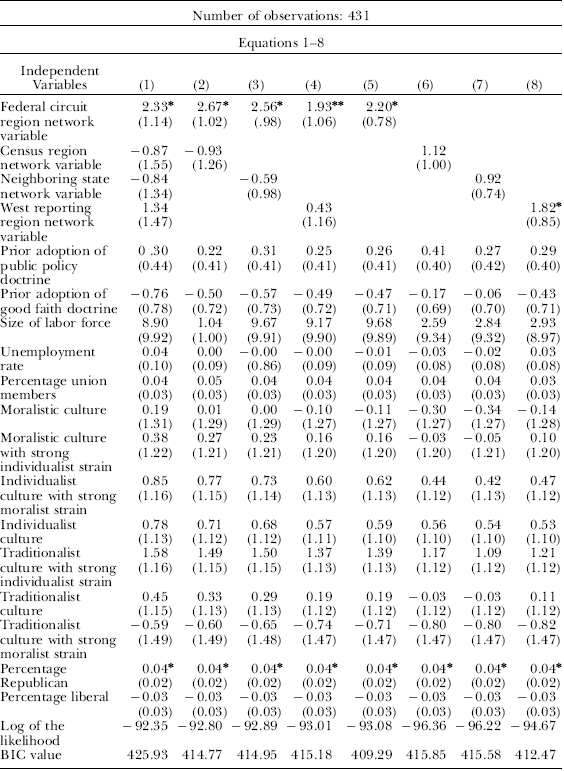

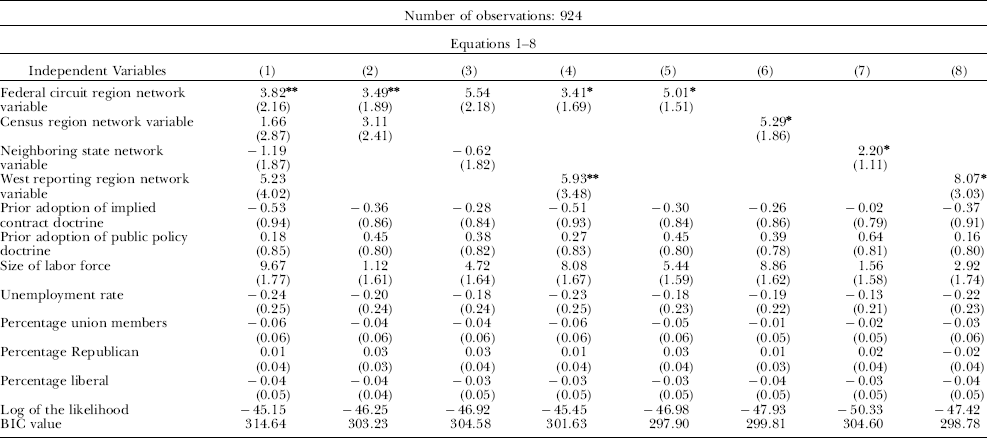

Table 2 reports results from complementary log-log regressions in which the implied contract exception is the dependent variable.Footnote 24 The results are quite striking and surprisingly robust.

Table 2. Complementary Log-Log Regressions With the Implied Contract Doctrine as the Dependent Variable

The coefficients are on top; the standard errors are in brackets. All estimates have been rounded to two decimal places.

* Statistically significant at the 95 percent level of confidence.

** Statistically significant at the 90 percent level of confidence.

As Column 1 indicates, when all the implied contract network variables are included in the estimations, the one that uses the federal circuit regions to define the reference groups is clearly dominant. It is the only network variable whose coefficient is both positive and statistically significant (at the 95 percent level of confidence). As columns 2–4 indicate, when the federal circuit network variable is included in the regressions with each of the other network variables individually, it is again the only one that is both positive and statistically significant (although when it is run against the network variable defined using the West reporting regions as the reference groups, it is only significant at the 90 percent level of confidence). As columns 5–8 indicate, when the estimations are done on each of the network variables individually, only the ones defined for the federal circuit regions and the West reporting regions are both positive and statistically significant.

In light of the strong correlations between the network variables, these results are quite surprising. Indeed, these are the most striking and robust result of the entire study: decisions to adopt a new employment doctrine by other courts within the same federal circuit region appear to dominate decisions to adopt the new employment doctrine by other courts in neighboring states, the same West reporting region, or the same census region. There is a very strong and distinctive social network effect in the diffusion of the exceptions to the employment-at-will rule, and it is one that appears to operate most strongly through reference groups defined by the federal circuit regions.

It is interesting to observe that prior adoptions of one or both of the other exceptions to the employment-at-will rule by a state's courts do not appear to influence their propensity to adopt the implied contract exception. Thus, courts' decisions about whether to adopt the implied contract exception appear to be independent of any prior decisions they made to adopt either the public policy or good faith exceptions.

None of the economic variables has a positive and statistically significant effect in any of the estimations. Indeed, this is true when they are tested both individually and collectively. Likelihood ratio tests reject the hypotheses that all three or any two of them are statistically significant. While the implied contract doctrine may have consequences for states' labor markets, therefore, labor market conditions and the size of the labor market do not have a statistically significant effect on the diffusion of the implied contract doctrine across the states.

It is interesting to note that one of Reference Erikson and CohenErikson and colleagues' (2006) political variables—the proportion of the state's respondents that identified themselves as Republicans in the CBS/New York Times polls—is positive and statistically significant in all the estimations. This suggests that a state's courts were more likely to have adopted the implied contract exception to the employment-at-will rule if its voters were more likely to have identified themselves as Republicans than Democrats. While one might have expected a state's political orientation to influence the evolution of its employment laws, it is difficult to understand why a Republican orientation, and presumably a more conservative, pro-market political leaning, should have increased the likelihood that state employment law would have deviated from the employment-at-will rule. Indeed, this Republican orientation may have been only coincidentally rather than causally related to the adoption of the implied contract doctrine. Many state courts adopted the implied contract exception during the early to middle 1980s. This was, of course, right in the middle of the Reagan presidency, and it coincided with President Ronald Reagan's second-term electoral sweep. Regardless, all of the results in Table 2 are robust to the exclusion of the political variables.

The Public Policy Exception

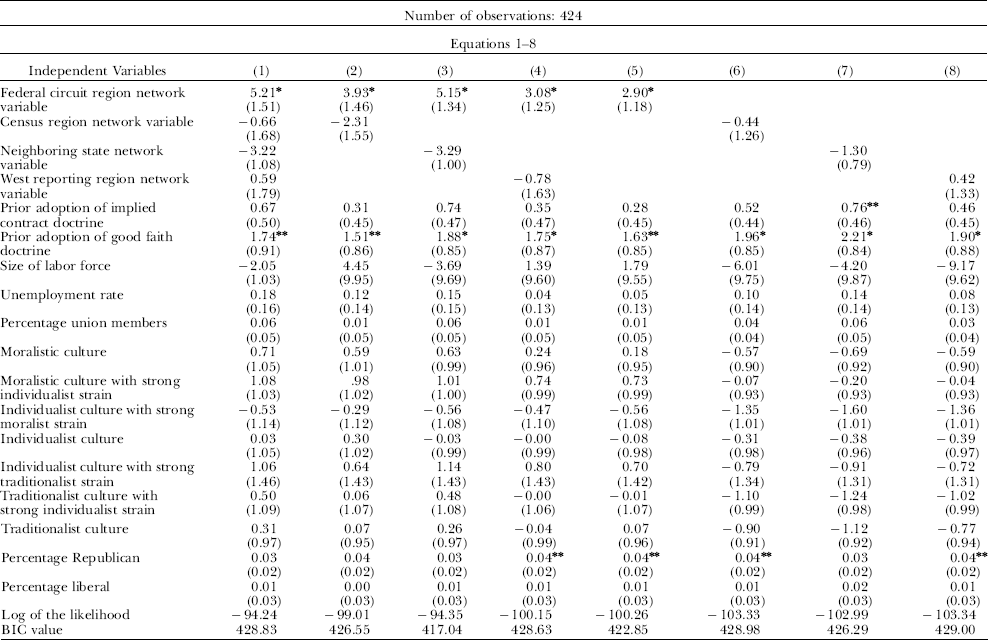

Table 3 reports results from complementary log-log regressions in which the public policy exception is the dependent variable.Footnote 25 These results are also quite striking, and very similar to those obtained for the implied contract exception.

Table 3. Complementary Log-Log Regressions With the Public Policy Doctrine as the Dependent Variable

The coefficients are on top; the standard errors are in brackets. All estimates have been rounded to two decimal places.

* Statistically significant at the 95 percent level of confidence.

** Statistically significant at the 90 percent level of confidence.

As column 1 indicates, when all the network variables are included in the estimations, the one that is defined using the federal circuit regions as the reference group clearly dominates once again. It is the only one that is both positive and statistically significant. As columns 2–4 indicate, when the federal circuit network variable is run against each of the other network variables individually, it is again the only one that is both positive and statistically significant. And as columns 5–8 indicate, when the regressions are done using each network variable individually, only the network variable defined using the federal circuit regions as the reference groups is both positive and statistically significant. Thus, a strong social network effect appears to be at play in the diffusion of the public policy exception also, and it again appears to operate most strongly through reference groups defined by the federal circuit regions.

It is interesting to observe that a state's prior adoption of one of the other exceptions to the employment-at-will rule—especially the good faith exception—appears to have increased the likelihood that it would adopt the public policy exception. The variable defined to reflect the prior adoption of the good faith exception is positive and statistically significant in all of the estimations reported in Table 3. The variable defined to reflect the prior adoption of the implied contract exception is positive and statistically significant in some of the estimations, although this result is very sensitive to which of the network variables are also included in the estimations.

None of the economic variables are statistically significant in any of the estimations. This suggests that economic factors had little, if any, influence on courts' decisions about whether to adopt the public policy exception to the employment-at-will rule. Once again, the only political variable that is statistically significant in any of the estimations is the proportion of the state's respondents that identified themselves as Republicans in the CBS/New York Times polls. This time, however, it is significant in only some of the estimations and only at the 90 percent level of confidence.

The Good Faith Exception

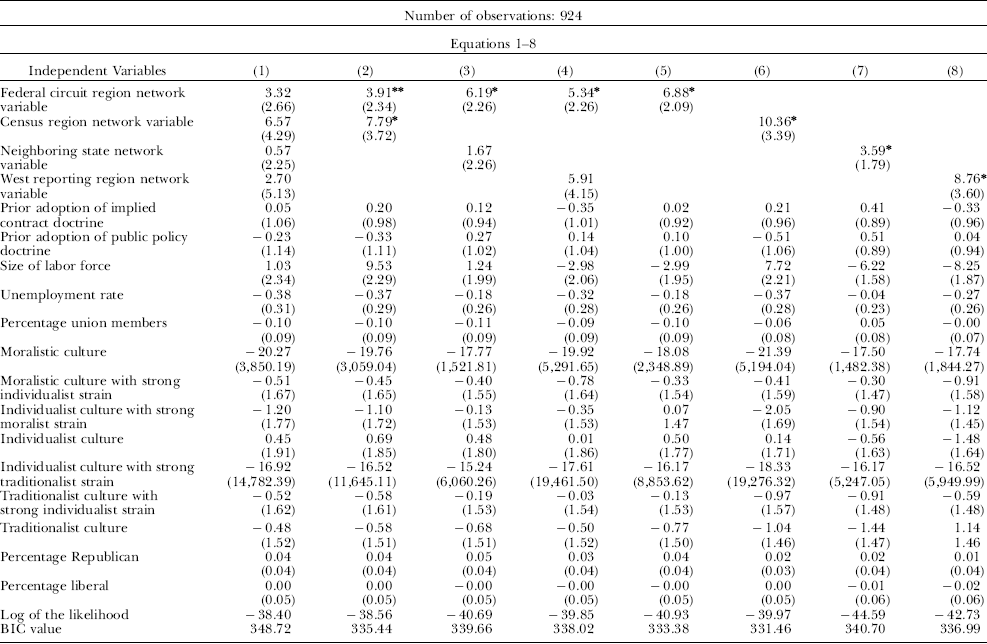

Tables 4 and 5 report results from complementary log-log regressions in which the good faith exception to the employment-at-will rule is the dependent variable.Footnote 26 Although these results are generally consistent with those obtained for the implied contract and public policy exceptions, they are not as robust. In particular, they appear to depend on whether Elazar's variables reflecting the states' political subcultures are included or excluded from the estimations.

Table 4. Complementary Log-Log Regressions With the Good Faith Doctrine as the Dependent Variable Including the Elazar Variables

The coefficients are on top; the standard errors are in brackets. All estimates have been rounded to two decimal places.

* Statistically significant at the 95 percent level of confidence.

** Statistically significant at the 90 percent level of confidence.

Table 5. Complementary Log-Log Regressions With the Good Faith Doctrine as the Dependent Variable Excluding the Elazar Variables

The coefficients are on top; the standard errors are in brackets. All estimates have been rounded to two decimal places.

* Statistically significant at the 95 percent level of confidence.

** Statistically significant at the 90 percent level of confidence.

Table 4 reports results from estimations in which the Elazar variables are included. Column 1 reports the results of a complementary log-log regression in which all of the network variables are also included. In this case, none of the network variables appears to dominate. None of them is statistically significant at even the 90 percent level of confidence. As column 2 indicates, when the network variable defined using the federal circuit regions is run against only the network variable defined using the census regions, both are positive and statistically significant (although the one defined using the federal circuit regions is significant at only the 90 percent level of confidence, whereas the one defined using the census regions is significant at the 95 percent level of confidence). Moreover, when the estimations are done using each of the network variables individually, the one defined using the census regions has a higher BIC value than the one defined using the federal circuits.Footnote 27 While this suggests that the federal circuit regions may have been important in the diffusion of the good faith exception, the reference groups they defined did not clearly dominate reference groups defined using the census regions.

Table 5 reports results from complementary log-log regressions in which the good faith exception is the dependent variable, but the Elazar variables are not included in the estimations. Column 1 indicates that when all the network variables are included, only the one defined using the federal circuit regions is positive and statistically significant (although only at the 90 percent level of confidence). As columns 2–4 indicate, when the regressions are run on the federal circuit network variable against the others individually, the federal circuit variable is positive and statistically significant in each case. The only other network variable that is positive and statistically significant is the one that uses the West reporting regions to define the reference groups. As columns 5–8 indicate, however, when the regressions are done on each of the network variables individually all are both positive and statistically significant. The regression with the lowest BIC value is the one that uses the federal circuit network variable, although the BIC value is only marginally lower than in the other regressions.

The results thus suggest that the federal circuit regions defined important reference groups in the diffusion of the good faith exception but that they did not clearly dominate the other reference groups. Interestingly, none of the economic or political variables are statistically significant in any of the regressions, regardless of whether the Elazar variables are included or excluded. Indeed, it is important to remember that the good faith exception never diffused as widely as the implied contract or public policy exceptions. Given that it was never widely adopted, it is not surprising that it seems more difficult to identify any pattern in its diffusion.

Discussion

The most interesting implication of this study is that the federal circuit regions appeared to play an important role in the diffusion of all three exceptions to the employment-at-will rule. The results thus suggest that there may be an interesting pattern of intra-circuit communication and influence among state judges. Indeed, there are other reasons to believe that intra-circuit communications are important. State courts within the same federal circuit are influenced by the same federal circuit precedents on habeas corpus petitions, certification questions, abstention issues, death penalty cases, concurrent jurisdiction, and bankruptcy issues that affect state claims, among others (Symposium 2005; Reference ArmatasArmatas 2002). State judges may also find new precedents on questions of state law by courts within the same federal circuit region more persuasive than new precedents by courts outside of the region.

Unfortunately, no research has been done yet on the extent and impact of intra-circuit communication among state judges. The closest useful analogue is research on intra-circuit communications among federal judges. Reference CarpCarp (1972), for instance, explored the intra-circuit communication between federal district and appellate judges in the Eighth Circuit. He found that judges communicate intra-circuit in a variety of ways, such as through circuit judicial conferences, informal social contact, daily personal contact, and correspondence. Carp's analysis of an Iowa federal judge's personal papers, for instance, revealed that the vast majority of the judge's correspondence was based upon communication within his federal circuit. This did not appear to be due to mere geographic contiguousness. Carp noted that the judge communicated frequently with judges in Arkansas and North Dakota, noncontiguous states that comprise part of the Eighth Circuit. There was not a single piece of correspondence, however, between the judge and federal judges in Illinois or Wisconsin, contiguous states outside the Eighth Circuit. Carp also cited the importance of state bar association meetings and professional journals in the intra-circuit communications between federal judges. Since state court judges likely attend the same state bar association meetings and read the same professional journals as the federal judges within their circuit, and since state court judges within the same circuit have common interests in a variety of legal issues, the federal circuits may shape the pattern of communication and influence among state judges as well as federal judges. State court judges may thus reflect the same local and regional influences as federal district judges (Reference Stidham and CarpStidham & Carp 1988).

Intra-circuit communications among state judges may also have been increased by the State-Federal Judicial Councils, which were established in the early 1970s to help facilitate communication between state and federal judges. The councils are often organized by federal circuits and always include federal as well as state judges from a particular state (U.S. Courts 2003). But the councils can and do bring together state judges from across states. The councils formed for New York and Connecticut, for example, meet on a regular basis to resolve problems of mutual interest. The Seventh Circuit has also held joint judicial councils for state and federal judges within the Seventh Circuit (U.S. Courts 2003). Meetings such as these provide opportunities for state judges from the same federal circuit to discuss a variety of doctrinal matters (Annual Judicial Conference 1987). They may facilitate and reinforce a pattern of communication and persuasion between state courts within the same federal circuit.

The literature tends to corroborate the conclusion that economic factors did not play a role in the diffusion of the employment doctrines. Reference Walsh and SchwarzWalsh and Schwarz (1996) reviewed precedent-setting state wrongful-discharge cases and found nine, 14, and 38 rejections of the public policy, implied contract, and good faith doctrines respectively. Out of the 61 rationales given by state courts refusing to adopt one of the three exceptions, only one court cited an economic reason, noting that the adoption of the doctrine would harm the state's ability to attract new businesses. It seems likely, therefore, that judges usually base their decisions on legal authorities rather than policy considerations or economic conditions.

Nonetheless, there are some important limitations to this study. It is possible that the economic variables may have had different effects at different stages of the legal process. For instance, it is possible that a high unemployment rate might have caused more wrongful-discharge claims to be made, but that judges may have simultaneously been less likely to rule in their favor because of the weak employment conditions. In this case, the positive effect of the unemployment rate on the likelihood of a wrongful-discharge claim being made would be offset by the negative effect of the unemployment rate on the likelihood that a judge would rule in its favor and thus adopt the wrongful-discharge doctrine as state law. The economic variables may thus have had complicated and offsetting effects at different stages of the legal process that cannot be separated in the present student and merit further research. It is also possible that the use of binary variables for each of the years of the sample may have captured the effects of the temporal variation in the economic variables and that the reported estimates therefore reflect only the effects of the cross-sectional variation.

The results of this study have implications for lawyers, business managers, policy makers, political advocates, and anyone else who might want to predict or initiate changes in the law. An employment lawyer during the 1980s would have been well-advised to follow legal developments within the federal circuit region carefully in assessing the likelihood of an imminent change in a state's wrongful-discharge laws. Human resource managers would also have benefited from an understanding of the particular importance that legal developments within the federal circuit region might have for the state law that applied to their own organizations' employees. Indeed, Reference EdelmanEdelman and colleagues (1992) conducted an extensive study of the ways in which legal and human resource professionals actually responded to developments in wrongful-discharge laws during the 1980s. Although they found that both groups tended to exaggerate the threat to their organizations, they also found significant evidence that their advice initiated important organizational responses. Their study thus corroborates the importance of predicting the diffusion of new laws for actual organizational practices. Indeed, as Reference EdelmanEdelman (1990) and Reference Edelman and SuchmanEdelman and Suchman (1999) have argued, organizations have often responded to changes in their legal environment with significant new administrative procedures that have effectively “internalized” the law.

Conclusion

This article focuses on how the social structure of legal institutions influences the diffusion of new state laws. It assumes that the American legal system is a social network, like any other, and attempts to draw inferences about the pattern of social influence between judicial actors. To that end, it uses social network theory and hazard analysis to evaluate the role of legal precedents in the diffusion of three exceptions to the employment-at-will rule in American employment law over the period from 1978 to 1999. It also attempts to evaluate the role of economic and political factors in the diffusion process. Two robust results stand out: (1) precedents by courts within the same federal circuit region tended to be the most influential, and (2) economic variables reflecting labor market conditions did not have statistically significant effects on the diffusion of any of the exceptions. There was, in addition, some evidence that political factors may have influenced the diffusion processes and that prior adoptions of another exception may have had some limited influence.

The federal circuit effect was surprising—all the more so because it arose in the diffusion of new state laws rather than the diffusion of a new precedent on a question of federal law and from the decisions of state courts rather than the decisions of federal courts. The dominance of the federal circuit network variable may suggest that the federal circuit regions play an important role in initiating new lawsuits, or it may suggest that precedents by other courts within the same federal circuit region are particularly persuasive. Regardless, it implies that the social structure of American legal institutions—in particular, the administrative structure of the federal courts—may have had and may continue to have an important influence on the evolution of state law. Further research will be necessary to determine whether this effect was unique to the diffusion of the exceptions to the employment-at-will rule or whether it is a more pervasive phenomenon in the diffusion of new state laws.

Indeed, the results of this study suggest a number of potentially fruitful avenues for future research. Obviously, further studies of the diffusion of new state laws would be helpful in determining whether the federal circuit network effect is also evident in the diffusion of other state laws. In conjunction with such studies, further research on the nature and extent of communications between judges and the consequences for their judicial decisions would also be very enlightening. This study was unable to separate out the effects of the variables on the various stages of the legal process; research directed at understanding the role that network effects and economic and political variables play at each of the stages in the legal process might also yield many nuanced insights. Further studies that attempt to assess whether some states' courts are more sensitive to political trends than other states' courts might also be particularly interesting. One possibility is that the manner in which a state's judges are selected may be important; elected judges, for example, may be more sensitive to political currents than judges who are appointed.

Finally, this study has implications for lawyers, business managers, policy makers, political advocates, and anyone else who might want to better predict or more effectively initiate changes in the law. It also has implications, therefore, for our understanding of the responses of economic and political actors to changes in their legal environments. Further research on the responses of economic and political actors to changes in their legal environments that integrates social network analysis might also prove to be particularly fruitful.