1. INTRODUCTION

As environmental courts and tribunals have proliferated across the globe, interest in these institutions continues to increase. Environmental courts are now found in diverse domestic contexts,Footnote 1 and varied actor classes are promoting their establishment,Footnote 2 including intergovernmental organizations,Footnote 3 regional organizations,Footnote 4 legal scholars,Footnote 5 and judges.Footnote 6 The diversity of forms and functions assumed by environmental courts across legal cultures and political settings complicates generalization.Footnote 7 In the light of their widespread diffusion, it is nonetheless valuable to consider broadly the governance implications of these specialist institutions. Environmental courts offer potential spaces for experimentation and innovation, in line with the recently highlighted contributions of domestic courtsFootnote 8 and domestic judgesFootnote 9 to the governance of complex, systemic global environmental challenges.Footnote 10

At present, all environmental courts and tribunals are situated domestically,Footnote 11 and no international environmental court currently exists. Their diverse settings, coupled with the wide range of their jurisdictional, procedural, and functional characteristics, raise compelling questions about the capacity of individual environmental courts to support global environmental governance (GEG). In particular, the specialist attributes of such courts and the complex environmental issues they encounter suggest that they may be uniquely positioned to facilitate the domestic interpretation and application of international environmental law (IEL) norms, including polluter pays, sustainable development, intergenerational equity, and precaution.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, individual court capacity to support such application of IEL norms, and IEL principles more broadly, may vary considerably.

This article explores the implications of environmental courts’ institutional features for judicial contributions to GEG and the application of IEL norms and principles.Footnote 13 In so doing, it offers initial answers to three questions:

(1) Which institutional factors may influence an environmental court's capacity to identify and apply norms of IEL in its decisions?

(2) How can these institutional factors be conceptualized to assess the capacity of environmental courts to identify and apply IEL norms?

(3) To what extent do existing domestic environmental courts exhibit the institutional capacity to identify and apply IEL norms in decision making?

In answering these questions, this article couples theoretical analysis with a census and subset analysis of eight existing environmental courts. It integrates existing environmental court knowledge with insights from multiple subdisciplines (notably, environmental law and global environmental politics (GEP)), and qualitative institutional analysis. Researchers have demonstrated that the environmental court model has been promoted by diverse authors, each bearing diverse motivations,Footnote 14 and they have posited that individual institutions are likely to vary in form and capacity.Footnote 15

Earlier studies have explored environmental courts through in-depth single-case studiesFootnote 16 and examinations of decision-level attributes.Footnote 17 Others explore their diversity through analyses,Footnote 18 including theoretical and comparative examinations,Footnote 19 which seek to identify environmental court outcomes.Footnote 20 Most existing scholarship highlights desirable environmental court attributes and emphasizes outcomes resulting from courts incorporating these best-practices elements.Footnote 21 Notwithstanding some notable exceptions,Footnote 22 researchers generally laud environmental courts’ potential contributions to access to justice and environmental outcomes,Footnote 23 particularly when compared with generalist courts.Footnote 24 However, how exactly institutional design factors relate to desirable outcomes remains poorly understood.

The institutional embeddedness of environmental courts renders a comparative lens valuable to support richer understanding of norm interpretation,Footnote 25 entrepreneurship,Footnote 26 and contestation.Footnote 27 The importance of comparative analysis to reflect and support a broader understanding and reimagination of IEL has been stressed repeatedly by environmental law researchers,Footnote 28 as well as governance scholars.Footnote 29

This article represents an initial, theoretically and methodologically explicit analysis of how environmental courts and tribunals may support domestic application of IEL norms. Firstly, I review how structural factors influence the domestic application of IEL norms. I expand this discussion beyond pure IEL scholarship, referencing (i) GEP and GEG literature exploring norm dynamics and circulation, and (ii) legal research examining structural determinants of court capacity.

Secondly, I use these insights to identify structural attributes that, in theory, might equip a court to interpret and apply IEL norms in its domestic opinions. I note that courts situated at any level of a country's judiciary, and bearing any combination of structural attributes, can interpret and apply IEL. However, by constructing a theoretical typology, I suggest that the likelihood of an individual court applying IEL will vary according to these structural factors. I hypothesize that, all else being equal, a court with national geographic jurisdiction that also enjoys attributes of broad subject-matter jurisdiction and discretion may be expected to be best equipped to perform this function.

Thirdly, I couple theory with empirical analysis. I integrate existing assessments of environmental court presence with original outreach and web research to identify all countries that possess environmental courts. Among these, I note eight environmental courts that enjoy national geographic jurisdiction and then consider their attributes as relevant to jurisdiction, discretion, and theoretical capacity to interpret and apply IEL.

Fourthly, I consider how these findings might inform our understanding of environmental court contributions to environmental governance. I urge that (i) the IEL interpretation and implementation capacity of existing environmental courts and tribunals offers cause for both caution and optimism; (ii) environmental courts offer a useful case study to examine how domestic institutional capacity affects international norm circulation and contestation; and (iii) domestic environmental courts merit further recognition and analysis for their contributions to GEG.

This analysis makes three key contributions. Firstly, researchers have long highlighted the centrality of judicial agency and discretion in IEL.Footnote 30 This study emphasizes the simultaneous importance of evaluating the institutional characteristics and preconditions that can influence the extent and effectiveness of judicial discretion and judges’ incorporation of IEL norms in their work. Secondly, as GEP scholars have long recognized, domestic institutions contribute directly to the architecture of global governance in climate and other regimes.Footnote 31 This study emphasizes domestic courts, and specifically specialist environmental courts, as an important but as-yet understudied component of GEG architecture. Thirdly, the project underscores the value of IEL's detailed decisional insights,Footnote 32 especially when coupled with the formalized, comparative analysis commonly employed in GEP.Footnote 33 Therefore, it demonstrates the benefit of additional interdisciplinary work at the nexus of IEL, GEP, and earth system governance (ESG).

2. ENVIRONMENTAL COURTS AND IEL NORMS

Numerous publications have described environmental courts in developed countries,Footnote 34 as well as within developing jurisdictions;Footnote 35 noted individual courts’ attributes,Footnote 36 outcomes,Footnote 37 and procedures;Footnote 38 and considered the implications of their emergence.Footnote 39 More generally, interest in environmental courts and tribunals aligns with growing attention to how domestic courts and judges address systemic environmental challenges, including climate change.Footnote 40 It also complements broad interest in understanding how courts at international and domestic levels apply IEL norms and principles,Footnote 41 including the principles of polluter pays,Footnote 42 common but differentiated responsibilities,Footnote 43 and sustainable development,Footnote 44 and the precautionary principle.Footnote 45

2.1. Environmental Courts and Tribunals as Agents and Sites of IEL Norm Application

The engagement of environmental courts and judges with global norms and transboundary issues is highly relevant to IEL and GEP considerations of structures and agents.Footnote 46 In turn, both IEL and GEP advance research in international law and international relations which examines the relationship between domestic legal structures and global processes. Though the two disciplines conceive of ‘norms’ somewhat differently,Footnote 47 both explore how shared conceptions of collective expectations evolve, gain acceptance, and diffuse.Footnote 48 For instance, comparative law scholars examine legal transfer and transplantation,Footnote 49 while international relations scholars examine norms and the dynamics driving their diffusion and adoption.Footnote 50

Additionally, it is essential to understand how IEL norms are operationalized and given domestic effect,Footnote 51 as it can clarify the role of norm agents and entrepreneurs,Footnote 52 norm diffusion,Footnote 53 and norm circulation.Footnote 54 Researchers regularly highlight the iterative relationship between domestic structures and global norms.Footnote 55 They also emphasize how domestic institutions, including courts,Footnote 56 can be equipped to identify and implementFootnote 57 international norms.Footnote 58 Collectively, domestic courts contribute substantially to the application of, and compliance with, international law.Footnote 59 Understanding these domestic implementation dynamics is urgent,Footnote 60 given the ongoing fragmentation,Footnote 61 decentralization,Footnote 62 and bottom-up character of GEG,Footnote 63 especially in recent international environmental conventions.Footnote 64

Under what conditions can environmental courts and tribunals support domestic applications of IEL norms? Researchers have explored this question both implicitly and explicitly.Footnote 65 Studies suggest that environmental courts and tribunals may advance environmental law principles and rights,Footnote 66 promote access to justice,Footnote 67 redress a perceived lack of ‘visionary decisions’ that ‘meet national and international norms’,Footnote 68 and ‘help in advancing the cause of environmental justice’.Footnote 69 Individual environmental courts may choose, or even be obligated, to apply norms of IEL when issuing judgments.Footnote 70 Despite widespread excitement about their potential to strengthen the international environmental rule of law,Footnote 71 environmental courts are incredibly diverse. Their individual and collective capacity to apply IEL norms depends on several factors that require careful analysis.

2.2. Factors Influencing Environmental Court Implementation of IEL

Among environmental courts, many facets can shape the effectivenessFootnote 72 and application of IEL norms. These may include contextual factors, such as whether a court is located in a common law or civil law jurisdiction, or individual-level factors, such as the training of an individual environmental court panellist. At the institutional level, I single out three attributes that are drawn from the existing literature and input gathered from environmental court scholars and practitioners through an original expert survey:Footnote 73 (i) an environmental court's substantive jurisdiction, (ii) the discretion afforded to environmental court jurists, and (iii) an environmental court's geographic reach and position within domestic legal contexts.

The first attribute, jurisdiction, broadly represents ‘the power of a court to adjudicate cases and issue orders’.Footnote 74 This power stretches across multiple dimensions, including the subject matter a court may review, statutory grants of authority, and whether a court can hear a case involving a given defendant,Footnote 75 with each presenting potential ‘jurisdictional obstacles to litigation’ that constrain the application of IEL.Footnote 76 Researchers, therefore, largely advocate environmental court jurisdiction that is ‘as comprehensive as possible’.Footnote 77 They identify ‘lack of jurisdiction’Footnote 78 as a key bar to a court's ability to implement IEL effectively, and they note that practices such as separating criminal and civil jurisdiction can impair ‘the effective administration and understanding of environmental issues’.Footnote 79 Therefore, existing insights suggest that, all else being equal, environmental courts with broad jurisdiction would be better able to incorporate IEL norms in domestic judgments.Footnote 80

Secondly, the application of IEL norms can be influenced by the discretion, or flexibility, granted to environmental court panellists. Judicial discretion is a relative concept, representing the latitude afforded to jurists by various structural attributes.Footnote 81 Discretion describes a type of bounded freedom, allowing judges flexibility within the scope of statutory and procedural mandates when applying the law and seeking justice in a given case.Footnote 82 Judges with greater discretion can ‘exercise … judgment based on what is fair under the circumstances and guided by the rules and principles of law’.Footnote 83 Some existing environmental courts have granted panellists flexibility to employ innovative practices,Footnote 84 or to deviate from procedural requirements that bind generalist courts.Footnote 85 Scholars note that a ‘lack of flexibility in court rules and procedures [makes] it impossible to respond to international environmental laws and standards’Footnote 86 and advocate ‘the authority to impose a variety of civil, administrative and criminal penalties’.Footnote 87 Elsewhere, researchers and practitioners advocate ‘creativity in designing remedies’Footnote 88 and a ‘willingness and capacity to incorporate IEL and associated norms and principles into their judgments’.Footnote 89 Therefore, a domestic environmental court which grants its panellists broad discretion may be expected, all else equal, to be better-equipped to interpret and apply IEL norms in decision making.

Thirdly, a court's geographic reach and position within a domestic legal system can influence its awareness or receptiveness to IEL norms and the types of question that it addresses. While judicial specialization may be well suited to localized, first-instance courts,Footnote 90 where technical fact finding occurs, dialogue and exchange among national-level appellate judges is widely advocated as key to international law development.Footnote 91 Climate jurisprudence, for instance, is increasingly moulded by judicial borrowing, influence, and transplantation among apex court judges.Footnote 92 Exchanges among domestic institutions can advance environmental justice by promoting ‘access to effective, transparent, accountable and democratic institutions’,Footnote 93 yet these efforts and exchanges may not be a focus of trial for more localized courts.Footnote 94 While subnational and trial-level environmental courts certainly influence and apply IEL,Footnote 95 those at the national level may be viewed as most likely, all else equal, to identify and apply IEL norms.

2.3. Environmental Court and Tribunal Typology

I constructed a 3×3 typology (Figure 1) to theorize the effect of substantive jurisdiction, discretion, and placement on the application and adoption of IEL norms. The resulting categories emphasize (i) the potential for variation among environmental courts across a judicial hierarchy, and (ii) that, at a given governmental level, a single institution may possess attributes of broad jurisdiction and discretion, narrow jurisdiction and discretion, or a combination. The typology does not permit fine-grained analysis of single environmental courts or of individual socio-political factors that may influence IEL interpretation capacity, such as a country's civil or common law legal system, its monist or dualist disposition to international law, or its unitary or federal legal system. However, it does support comparative analysis of norm dynamics.

Figure 1 Typology of Environmental Court Forms

The typology allows for the formulation of some initial hypotheses (Figure 2). Firstly, it predicts that local or municipal environmental courts, with their comparatively limited geographic scope, are least likely to interpret or apply IEL norms in their decision making. In contrast, environmental courts located at intermediate (e.g., state or regional) judicial levels are comparatively more likely to invoke IEL norms in their decision making, given their greater geographic remit and the capacity of some to engage in appellate decision making. Yet, institutions at this level vary widely in terms of institutional attributes and orientation, suggesting that this capacity is likely to be uneven.

Figure 2 Environmental Court and Tribunal IEL Norm Implementation Potential

Therefore, absent the establishment of a dedicated international environmental court,Footnote 96 it appears most likely, all else being equal, that those existing environmental courts with national geographic jurisdiction would be best positioned to interpret and apply IEL norms in decisions (Figure 2). The comparatively broad territorial jurisdiction of such institutions renders them most likely to engage with systemic environmental issues that may invoke IEL norms. Similarly, existing scholarship emphasizes the contributions of apex courts and judges of national high courts to environmental norm dialogue,Footnote 97 innovation, and learning.Footnote 98

Given these hypotheses, I conduct a detailed census of those environmental courts and tribunals that enjoy national geographic jurisdiction. Nevertheless, I again emphasize the potential for environmental courts at any level within a legal system to contribute to the application of IEL norms.

3. METHODS

3.1. Data Collection

I used a subsampling approach, informed by a point-in-time census, to identify national-level environmental courts and evaluate their capacity to engage with IEL norms. I used three approaches to seek all countries with documented environmental courts or tribunals:

(1) review of a 2016 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report,Footnote 99 regularly used to quantify environmental court establishment (‘list approach’);Footnote 100

(2) a web search of each United Nations (UN) member state's judicial system to identify environmental courts and tribunals (‘web approach’);Footnote 101 and

(3) direct outreach to each UN member state's (a) UN mission and (b) embassy to the United States (‘contact approach’).Footnote 102

To detect courts that one approach might overlook, while omitting erroneously identified courts or those falling beyond the scope of this project, I included only countries identified by at least two approaches (list, web, and contact). Finally, after identifying countries with environmental courts at any level, I used detailed web-based research and personal contacts to identify those with national-level courts meeting the project criteria.

Furthermore, I bounded the scope of institutions that this project seeks to identify in two ways, recognizing the variability of specialist courts.Footnote 103 Firstly, many institutional models can be characterized as environmental courts and tribunals, including quasi-judicial tribunals established within administrative agencies. However, this project seeks to examine institutions that may possess an outward orientation to norms of IEL. Therefore, I limit my sample effort to identifying formal, freestanding judicial institutions, though these may be termed ‘environmental courts’,Footnote 104 ‘environmental tribunals’,Footnote 105 ‘green courts’,Footnote 106 or otherwise, depending on the jurisdiction. Moreover, many jurisdictions have established specialist institutions with competence in anthropocentric domains that affect environmental quality, including water,Footnote 107 agriculture,Footnote 108 and sanitation.Footnote 109 Yet, given the objective of examining attributes that may shape engagement with systemic environmental challenges and norms, I focused here on courts which present themselves as centrally addressing environmental issues across issue domains and regimes.

3.2. National Environmental Court and Tribunal Characterization

Next, I collected data about each identified national-level environmental court or tribunal (Table 1). I coupled internet research with outreach to sitting judges (Kenya, Sweden), court registrars (New Zealand), local professors (China, India, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago), and attorneys (Bolivia).Footnote 110 I evaluated these data qualitatively to determine each court's jurisdiction and discretion/flexibility – and, in turn, its capacity to identify and apply IEL norms in decisions.

Table 1 Attributes Evaluated in Environmental Court Analysis

4. FINDINGS

4.1. Extent and Distribution

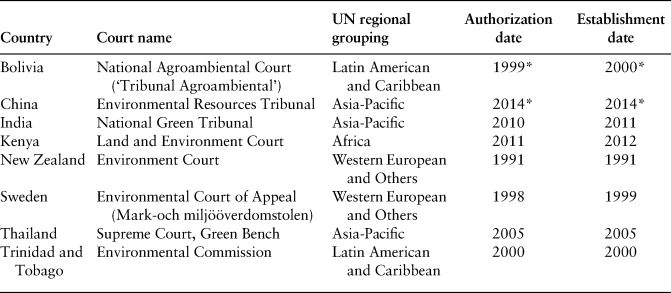

My point-in-time census, completed by 2018, identified clear evidence of stand-alone environmental courts or tribunals in 36 countries (Figure 3) and institutions with national geographic jurisdiction in eight (ibid.; Table 2). Those eight national-level courts are widely distributed geographically and in terms of longevity, with authorization and establishment spanning from 1991 to 2014 (Table 2).

Figure 3 Countries Identified with Environmental Courts and Tribunals at National Level (dark green) or Other Judicial Level (light green)

Table 2 National Environmental Court Geographical and Temporal Attributes

Note * Asterisk indicates uncertainty

4.2. Jurisdictional Elements

I observed wide variation among the eight institutions on attributes relevant to their jurisdiction. Four environmental courts (China, India, Kenya, Trinidad and Tobago) have civil jurisdiction, while the other four (Bolivia, New Zealand, Sweden, Thailand) appear to integrate both civil and criminal jurisdictional elements.

Similarly, institutional architecture exhibits variability (Table 3): two courts (China, Thailand) exist as components of broader supreme courts; two (Trinidad and Tobago, India) exist as institutions that interlink executive and judicial authority; one (Sweden) functions as an administrative court of appeal; and three (Bolivia, Kenya, New Zealand) operate as freestanding judicial courts with environmental jurisdiction.

Table 3 National Environmental Court Geographical and Temporal Attributes

Note * Asterisk indicates uncertainty

The subject-matter jurisdiction of nearly all institutions is broad (Table 3). Thailand's Supreme Court Green Bench enjoys jurisdiction over ‘about 24 Acts related to Environment’;Footnote 111 New Zealand's Environment Court can hear appeals under the country's Resource Management Act and ancillary statutes; Trinidad and Tobago's Environmental Commission may hear environmental appeals on numerous specified matters (Table 3). Likewise, at least three courts possess enabling legislation which explicitly affirms jurisdictional breadth. Kenya's Environmental and Land Court enjoys jurisdiction over ‘[a]ll disputes concerning the environment, title, use and occupation of land’;Footnote 112 India's National Green Tribunal enjoys ‘jurisdiction over all civil cases where a substantial question relating to environment … is involved’;Footnote 113 Bolivia's Constitution grants the Tribunal Agroambiental jurisdiction in a number of environmental issue areas ‘in addition to those [areas] indicated by law’.Footnote 114

4.3. Discretion and Flexibility

I observed substantial variation among elements that may affect judicial discretion or flexibility in rendering judgments (Table 4). Firstly, the panellists available to hear disputes in each court range from as few as two full-time and four part-time (Trinidad and Tobago) to as many as 41 (India) or even 150 (Thailand). Secondly, half of the courts (Bolivia, China, Kenya, Thailand) exclusively seat law-trained judges, while four others (India, New Zealand, Sweden, Trinidad and Tobago) have mixed benches of both law-trained judges and environmental experts. Thirdly, while most institutions seek jurists with considerable environmental expertise, there is substantial variation in the formalization of these training requirements. New Zealand's Environment Court imposes no formalized environmental training requirements upon its panellists;Footnote 115 Sweden expects judges to regularly attend training sessions on environmental issues;Footnote 116 Kenya's Land and Environment Court requires prospective judges to have at least ten years’ experience and annually attend at least two relevant continuing judicial education sessions.Footnote 117

Table 4 National Environmental Court Discretion and Flexibility Attributes

Notes

* Asterisk indicates uncertainty.

![]() Enabling legislation directly or indirectly references IEL norms or principles.

Enabling legislation directly or indirectly references IEL norms or principles.

I observed similar variation in dimensions relevant to judicial independence. In India, Kenya, New Zealand, Sweden, and Trinidad and Tobago, judges are appointed by the executive with judicial input, while Bolivian judges are nominated by the executive and then selected by popular vote. Panellists’ terms of appointment also vary widely across institutions, from limited (e.g., Trinidad and Tobago, minimum three years; Bolivia, maximum six) to lengthy (‘life’ appointments until age 67 in Sweden; 70 in Kenya and New Zealand).

Finally, I found considerable variation in whether and how courts’ enabling legislation formalized references to IEL norms. My analysis indicates that courts generally exhibit one of three main approaches. Firstly, in some jurisdictions, including China, environmental court-enabling legislation makes no apparent reference to IEL norms. Therefore, any incorporation of these elements in decisions would be accomplished voluntarily by panellists.

The second approach indirectly promotes formalized incorporation of IEL norms in opinions. Here, an environmental court's enabling legislation does not itself directly reference principles or norms of IEL, but instead obligates or empowers the court to implement or adjudicate statutes that do. For example, the Thailand Supreme Court Green Bench enjoys jurisdiction over at least two statutes that engage with IEL norms, including an environmental quality enactment which seeks ‘to protect the natural resources and environment, to remedy the effected [sic] areas, and the Polluter Pays Principle’.Footnote 118

In a third approach – the direct approach – legislation may explicitly obligate environmental courts to engage with IEL norms in rendering opinions. Bolivia's Tribunal Agroambiental must operate with regard to principles that include sustainability.Footnote 119 India's National Green Tribunal must, ‘while passing any order or decision or award, apply the principles of sustainable development, the precautionary principle and the polluter pays principle’.Footnote 120 Actions under Kenya's Environment and Land Court Act must reflect:

the principles of sustainable development, including the principle of public participation … the principle of international co-operation in the management of environmental resources shared by two or more states; the principles of intergenerational and intragenerational equity; the polluter-pays principle; and the pre-cautionary principle.Footnote 121

The Trinidad and Tobago legislation makes an apparent oblique reference to the principle of sustainable development: ‘The Environmental Commission shall … protect the rights of citizens while being cognizant of the need for the balancing of economic growth with environmentally sound practices’.Footnote 122 Collectively, these institutions demonstrate a promising, direct mechanism for mediating the incorporation of IEL norms.

4.4. IEL Application Capacity

By integrating the foregoing findings regarding individual court attributes, I develop a qualitative and relative placement of each court's theorized IEL implementation capacity (Figure 4). Doing so emphasizes the heterogeneity of existing environmental courts with regard to attributes that may be expected to affect their capacity to interpret and apply IEL norms in decision making.

Figure 4 Qualitative Evaluation of National-level Environmental Court/Tribunal Capacity to Implement IEL.

Note Qualitative assessments of court's jurisdiction (J) and discretion (D) are indicated by upper-case (broad) or lower-case (narrow) letters.

5. DISCUSSION

This article underscores the complexity and diversity of an emergent institutional model. It similarly emphasizes the need to further examine the capacity of environmental courts to interpret and apply IEL norms in decision making, both individually and collectively. These findings advance existing scholarship by nuancing assessments of environmental courts as venues to implement IEL (5.1); contributing to individual- and institutional-level debates in TEL and IEL scholarship (5.2); supporting norm circulation/contestation scholarship in GEG and GEP (5.3); and highlighting clear benefits of additional interdisciplinary scholarship at the nexus of IEL, GEP, and earth system governance (5.4).

5.1. Cause for Caution and Optimism in IEL Implementation Capacity

Despite widespread advocacy for,Footnote 123 and the rapid establishment of domestic environmental courts and tribunals, few currently exist with national geographic jurisdiction at higher appellate levels of judicial systems. Further, this project suggests that even fewer possess attributes that would best equip panellists to incorporate IEL norms in their decision making. While this project underscores challenges in generalizing across contexts, some trends may account for the comparatively limited establishment of environmental courts with broad geographic or appellate jurisdiction. Firstly, while many jurisdictions have considered specialist environmental courts,Footnote 124 some have intentionally chosen not to establish them,Footnote 125 based on a belief that environmental matters may be resolved effectively through generalist institutions.Footnote 126 Secondly, many jurisdictions that do establish environmental courts may view the courts as better suited to lower judicial levels, or to regional, provincial, or other subnational settings, where most technical fact finding occurs.Footnote 127 Thirdly, the establishment of environmental courts may still be constrained by their relative novelty and the complexity of importing the institutional form into complex domestic politics.Footnote 128 Regardless of cause, this study's finding of national environmental court diversity emphasizes that structural factors must be considered alongside the discretionary actions taken within individual cases or by individual judges.

However, the diversity observed among existing national environmental courts also offers cause for optimism. Firstly, the findings underscore the malleability of the environmental court model, implying its further potential to support domestic application of IEL in the Anthropocene. The eight institutions surveyed in detail illustrate diverse applications of practices which may facilitate the domestic application of IEL. For instance, while five of eight jurisdictions with national-level environmental courts or tribunals mandate the incorporation of IEL in their operations and decision making, they employ diverse statutory mechanisms to do so. Two institutions (Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago) use permissive or expansive language, and three (Bolivia, India, Kenya) specify the incorporation of certain IEL norms. Likewise, many of the eight institutions enjoy broad jurisdiction, yet this is operationalized in various ways: some enjoy permissive jurisdictional grants to broadly oversee environmental matters, while others are permitted to review numerous specified statutes and acts.

Finally, the eight identified institutions demonstrate diverse pathways for broadening discretion and flexibility in ways that might empower panellists to introduce IEL into domestic jurisprudence. Some invest panellists with life tenure, affording greater judicial independence; others employ ‘mixed benches’ of both scientific and legal experts who diversify the experiential and educational make-up of court personnel; and still others permit panellists to deviate from generalist procedure or evidentiary rules, offering space to innovate in resolving environmental disputes.

Ultimately, these findings underscore the potential of domestic environmental courts to support innovation in the face of complex environmental challenges. More broadly, domestic courts are recognized as key environmental governance institutions,Footnote 129 and judges are widely recognized,Footnote 130 in turn, for their potential to support innovation, particularly in the global south.Footnote 131 This project demonstrates that environmental courts can be particularly well adapted to situate domestic environmental disputes in their systemic, global context.Footnote 132 Furthermore, the eight national environmental courts demonstrate the malleability of the institutional model to varied settings. Thus, the foregoing assessment paints a nuanced portrait of IEL implementation capacity in individual courts, while also offering hope regarding the potential of environmental courts to support domestic judges in contributing to international judicial function.Footnote 133

5.2. Insights regarding Individual and Institutional Interplay

This study highlights the interplay between individual and institutional dynamics when examining how environmental courts influence IEL. Firstly, it shows that institutional attributes can influence the discretion enjoyed by judges. The differences in the approaches of environmental courts to panellist selection, training, and review highlight the need to understand how institutions condition judicial and expert engagement with global normative adoption, diffusion, and transfer. Existing research documents the importance of networked interactions among domestic environmental court judgesFootnote 134 and even suggests their collective status as an epistemic community which collaboratively advances responses to environmental challenges.Footnote 135 The study provides a necessary complement by underscoring that institutional attributes can affect judicial-level attributes and engagement, including judges’ familiarity with the existence of international lawFootnote 136 and their ability to apply international principles in domestic contexts.Footnote 137

Similarly, paying attention to the institutional attributes of domestic environmental courts helps to elucidate the interplay between domestic factors and IEL development. While most existing national-level environmental courts either enable or obligate panellists to incorporate IEL, their judicial training, selection, and oversight processes vary dramatically across courts. This finding echoes conclusions in the broader literature that domestic court engagement with international law frequently reflects institutional attributes, including whether a court has internalized international law and whether its jurisdiction explicitly directs it to address international law.Footnote 138 Research across legal issue areas,Footnote 139 including intellectual property and human rights,Footnote 140 already emphasizes that domestic statutes and contexts can affect a court's ability to employ international norms,Footnote 141 in some cases expanding the abilityFootnote 142 and elsewhere constraining it.Footnote 143 Finally, this study underscores the potential for productive integration between environmental court institutional analyses and broader research to examine the application of IEL in domestic courts.Footnote 144

5.3. Insights for Norm Circulation and Implementation

This study demonstrates a connection between environmental court scholarship and broader governance analyses of environmental norm circulation and adoption. Its focused analysis indicates that individual environmental courts vary in their attributes relevant to their capacity to adopt and apply IEL norms. These insights advance existing environmental policy and governance scholarship, which emphasizes the influence of context, local actors,Footnote 145 fit with local or regional setting,Footnote 146 and domestic ideology and culture.Footnote 147 However, few analyses concentrate exclusively on judges, and courts and tribunals judicial venues, instead frequently highlighting the complex milieu of public-private governance in specific normative regimes, including marine plastics,Footnote 148 single-use plastics,Footnote 149 and extractives.Footnote 150 Likewise, many existing efforts to evaluate environmental norm diffusion and legal transfer offer valuable process-focused insights regarding mechanisms and agents.Footnote 151 However, by centring analysis upon domestic courts and their attributes, this study highlights the importance of granting additional attention to structural institutional analysis. As formal institutions frequently provide toeholds for new environmental norms, these insights are crucial as diverse actors and institutions interpret and apply norms in context-dependent fashion, ‘particularly in the non-Western world’.Footnote 152

Similarly, this study's finding of institutional diversity among national environmental courts underscores the need for continued examination of domestic engagement with global environmental norms. Contemporary GEG and IEL are increasingly conducted less formally and centrally,Footnote 153 emphasizing the relevance of domestic institutional diversity, interpretation,Footnote 154 and the patchwork of institutions that differ in their legal character (organization, regimes, implicit norms).Footnote 155 This study's finding of broad diversity, even within a single institutional model, demonstrates that factors, including jurisdiction and discretion, can condition normative uptake and the context-dependent nature of domestic application. These insights demonstrate the direct relevance of environmental court scholarship to GEG and related academic discourses.

5.4. Value and Necessity of Interdisciplinary Environmental Court Analysis

Finally, the project's integration of legal analysis with environmental governance theory and methods highlights the utility of interdisciplinary environmental scholarship. It also demonstrates the bi-directional, additive benefits of interdisciplinary analysis in evaluating governance of urgent environmental challenges.

Legal scholars examining transnational environmental law and IEL advocate greater interdisciplinary scholarship.Footnote 156 In particular, they note the analytical insights offered by international relations and global governance,Footnote 157 and comparative environmental law scholars urge consideration of systemic interactions and processes,Footnote 158 exchanges facilitated between jurisdictions,Footnote 159 and dialogue through transnational networks.Footnote 160 Simultaneously, GEG scholars advocate heightened interdisciplinary attention to legal process and structures,Footnote 161 decentralized and complex environmental governance,Footnote 162 and environmental norm contestation in contemporary governance.Footnote 163 Therefore, by integrating IEL and GEP, researchers seeking to examine how process influences environmental norms can emphasize ‘a wider range of actors, paths, logics, and interactions, and allow … a much more detailed picture’ of diffusion.Footnote 164

This study highlights the practicability and benefits of an interdisciplinary approach by integrating attention to theoretical institutional attributes, attributes of existing institutions, and implications for IEL. Understanding the implications and capacity of environmental courts is enhanced by deeper context regarding IEL norms, their diffusion, and implementation mechanisms. Conversely, theoretical insights or prescriptions at the systemic level are strengthened by attention to individual institutions. Together, these approaches help to characterize the environmental court landscape while also offering prescriptions for future institutional development and analysis.

Nevertheless, this project provides only a point-in-time snapshot of a single class of environmental courts, rather than a comprehensive, ongoing census. Further, limitations in data access and availability constrained efforts to identify comprehensively all elements of all national-level environmental courts, and some may have been inadvertently neglected. More broadly, theoretically explicit accounts of environmental court establishment and implications remain limited, as do bridge-building efforts between IEL, GEP, and related disciplines, more generally. Accordingly, additional interdisciplinary efforts could extend this initial effort in several ways.

Firstly, future studies could repeat and deepen this census, extending its detailed attention to other classes of environmental court (especially those in state, provincial, and subnational settings). Likewise, studies could explore additional dimensions of environmental courts not characterized here. Both efforts would enhance existing efforts to understand the governance contributions and character of environmental courts. Secondly, this study examines the capacity of environmental courts to apply and implement IEL norms (an institutional-level analysis). However, future research could analyze the extent to which individual environmental court opinions incorporate these norms in practice – and how (a decisional-level analysis). This work would support contemporary efforts to better understand and quantify (i) environmental court outcomesFootnote 165 and (ii) the application of international environmental principles in domestic courts.Footnote 166 Finally, this project explicitly seeks to merge GEP and IEL insights. Nevertheless, opportunities exist to further expand the disciplinary and theoretical reach of environmental court analysis, including by better integrating with efforts in earth system lawFootnote 167 and global environmental lawFootnote 168 to conceptualize institutional innovation in systemic environmental governance.