I

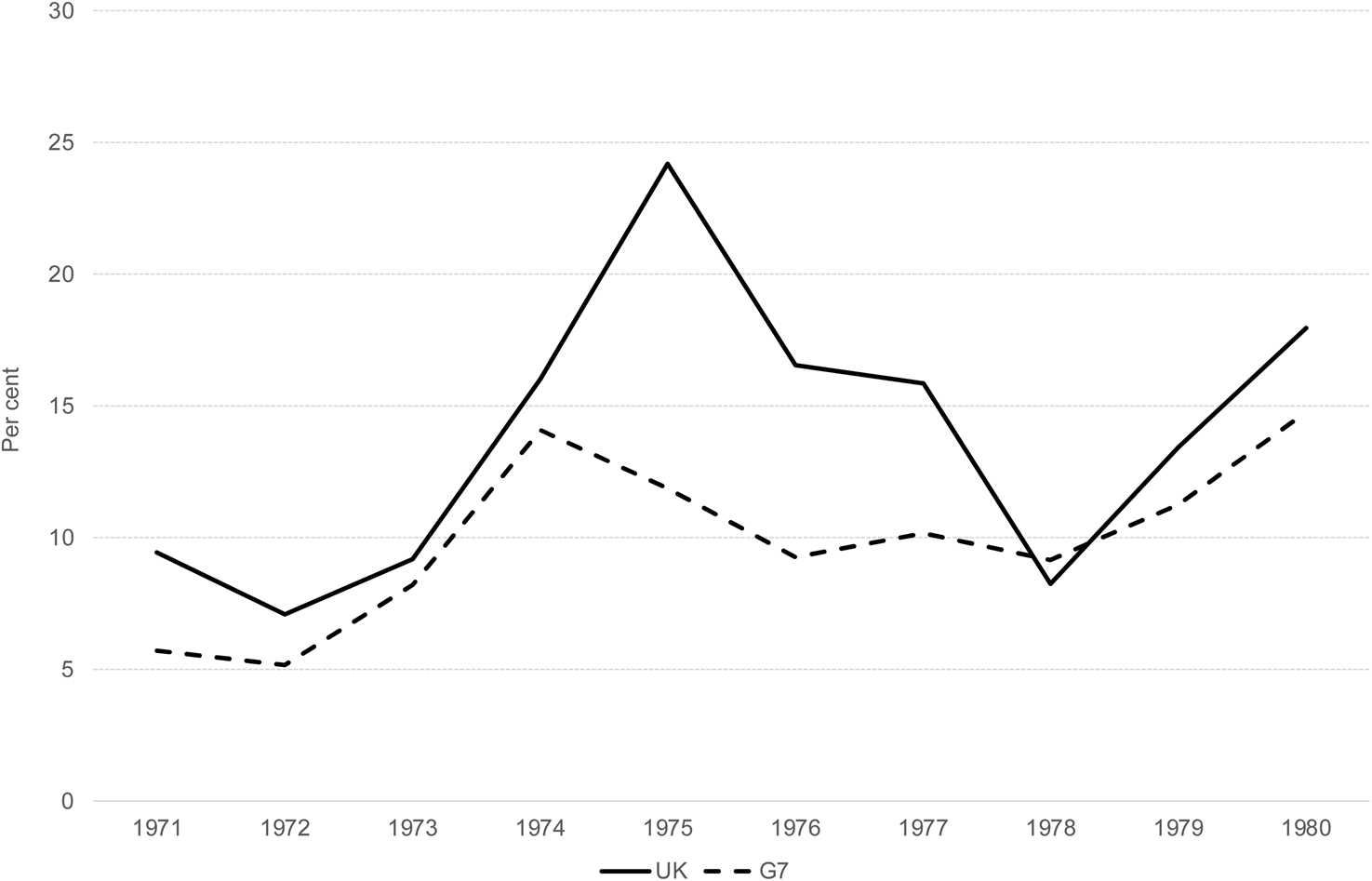

Following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s and the move to a regime of floating exchange rates, one of the biggest challenges facing economic policymakers was how to control inflation in a world without any internationally agreed monetary rules. The problem of inflation became pressing as changes in the pattern of world payments, increased global capital mobility and the oil shock of 1973–4 (OPEC 1) combined to inflict nominal and real shocks on the international economy. Although many countries struggled to adapt to the changing economic circumstances of the 1970s, the UK performed relatively badly (Table 1) and the increase in the rate of inflation among the G7 was particularly pronounced (Figure 1).

Table 1. Macroeconomic indicators in the 1970s

Note: Inflation estimated as compound growth rate of consumer price index; unemployment rates standardised; productivity growth – GDP per worker.

Source: Coopey and Woodward (Reference Coopey, Woodward, Coopey and Woodward1996, p. 3)

Figure 1. Consumer price inflation, UK and G7, 1971–9 (percentage change on previous year)

Source: OECD Statistics.

There are no monetary explanations for inflation in assessments of post-1945 economic history from well-known authors such as Cairncross (Reference Cairncross1992), Pollard (Reference Pollard1982, Reference Pollard1992) or Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson1986, Reference Tomlinson1990). There is no mention of inflation in the index of Booth's (Reference Booth2001) textbook, and in the narrative, the causes and cures of inflation are seen through a traditional Keynesian lens. For such authors, inflation post-1945 is explained by patterns of demand-pull (‘stop-go’) and then in the 1970s, cost-push (Brown Reference Brown1985). Insofar as the 1970s are concerned, Roger Middleton's (Reference Middleton2000, p. 115) assessment is more supportive of a connection between money growth and inflation when he writes ‘most economists would be comfortable with the proposition that the Heath government should not have allowed the loose monetary policy of 1971–3 that preceded the very high inflation rate that we now associate with the 1970s’.

A recent examination of the policy response to the UK's inflation problem in the 1970s has been provided by Nelson (Reference Nelson2005, Reference Nelson2009) and his co-authors (Nelson and Nikolov Reference Nelson and Nikolov2003, Reference Nelson and Nikolov2004; Batini and Nelson Reference Batini and Nelson2009; DiCecio and Nelson Reference Dicecio, Nelson, Bordo and Orphanides2013). Their analysis is formed from what they term the ‘monetary policy neglect’ thesis, which is based on two conflicting views of the inflation process. The first view is that inflation is a monetary phenomenon and that an easy monetary policy is responsible for producing inflation and a tighter monetary policy can reduce inflation. The alternative view is that inflation is purely nonmonetary and driven primarily by ‘cost-push’ factors which will dominate the behaviour of inflation, regardless of the course of monetary policy. The essence of their argument is that UK policymakers erroneously subscribed to the nonmonetary view of inflation, using nonmonetary measures (e.g. wage and price controls) and fiscal tightening as opposed to monetary tightening (Nelson and Nikolov Reference Nelson and Nikolov2004; Nelson Reference Nelson2009). Nelson argues that the apogee of monetary policy neglect occurred in the 1970s, with the highest levels of inflation in the twentieth century.

Along with an econometric analysis to illustrate this assertion, Nelson supports his argument by drawing on primary sources in the form of British Parliamentary volumes (speeches and testimony), newspaper articles and contemporary published speeches as well as some archival material. Additional archival support for Nelson's argument is provided by Forrest Capie in his history of the Bank of England from the 1950s to 1979. For Capie:

At the outset, financial stability was taken for granted; it was always there without anyone apparently having to do anything to maintain it. And monetary policy was downplayed in importance. But monetary policy conducted by neglect failed, and financial stability was lost. (Capie Reference Capie2010, p. 1)

In his account of British monetary policy post 1967, Duncan Needham (Reference Needham2014) disputes the monetary policy neglect thesis, noting how there were several experiments with monetary policy during the decade including Competition and Credit Control in 1971; the supplementary special deposits scheme in 1973; and targets for the broad money supply which were first published in 1976. Needham also accounts for the increasing importance attached to money growth by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and financial markets as the decade wore on. To support his arguments, he draws upon the available releases of archival files for the period and public pronouncements on monetary policy made by senior Bank officials and the published accounts of key advisers. For Needham (Reference Needham2014, p. 122), ‘it is the proponents of the monetary policy neglect hypothesis who have rewritten the monetary policy history of 1970s Britain’.

Needham's very different interpretation of the 1970s is due to how he construes neglect. Needham contends that because new monetary techniques were introduced, the authorities did not neglect monetary policy. Per contra, for Nelson, neglect is the failure to use monetary policy in a way likely to succeed. The central thrust of Nelson's thesis is that the authorities based monetary policy on an internally consistent but incorrect set of beliefs where a nonmonetary view of the inflationary process dominated. In light of this, any experiments with monetary policy were going to fail and inflation would not be controlled.

This article will examine the experiments with monetary policy during the first half of the 1970s when the nonmonetary view was dominant. However, during the second half of the 1970s, the authorities did move away briefly from a nonmonetary view of inflation, and this merits further investigation to determine if it confirms or contradicts the monetary policy neglect thesis. Drawing on archival sources, some of which were not available to Needham, and existing published accounts, this article is divided into five sections to consider the monetary and nonmonetary explanations for inflation in the 1970s. Section II provides a history of inflation in the 1970s to place the arguments by Nelson and Needham into a wider context. Section III explores how the UK authorities wrestled with monetary policy from the late 1960s to the mid 970s. Section IV considers the period between 1975 and 1979 to assess whether policy was still steeped in a nonmonetary view of inflation. Section V concludes.

II

In a chapter in a collection of essays on the British economy in the 1970s, Schulze and Woodward (Reference Schulze, Woodward, Coopey and Woodward1996) provide a slightly different approach from the traditional accounts by economic historians and explain the three peaks in inflation between 1967 and 1980 as being caused by nonmonetary and monetary factors (they label this an ‘eclectic’ approach).Footnote 1 Their explanation for the first inflation peak (using the retail price index, inflation rose from 2 per cent in 1967 to 10 per cent in 1971) is the 1967 devaluation of sterling and the transmission of US inflation to the rest of the industrialised world. Schulze and Woodward acknowledge that these only explain in part the rise of British inflation, which continued to increase as the impulses worked their way through the economic system. They argue that supply-side disturbances were an influence and cite the wage explosion of 1970–1, concluding that the wage bargaining situation was bound to deteriorate at some point (memories of high unemployment of the interwar years faded) as the trade unions became more bellicose and strains were placed on incomes policies from the late 1960s. Thus, the first inflation peak can be explained by an upsurge in world inflation coupled with a domestic wage-push, and whilst Rowlatt (Reference Rowlatt1988) gave both factors equal explanatory weight, she indicates that the most important source of inflation was the endogenous wage-price spiral.

In 1972 and 1973 inflation declined, but from the autumn of 1973 it began to rise again and rose to 15 per cent in 1974, reaching the second peak of 27 per cent in 1975 (again on a RPI basis). Schulze and Woodward conclude, however, that it would be wrong to attribute this second peak entirely to the primary commodity price increases and OPEC 1. Instead, they point to policy mistakes during the Heath–Barber years: fiscal reflation in 1971, tax cuts in 1972 and a significant loosening of monetary policy (which we return to below). Inflationary expectations were not well anchored by the design of the three-stage incomes policies with their destabilising effects.

Inflation began to rise again from 1978 where it stood at 11 per cent, reaching a peak of 21 per cent in 1980 (RPI basis). Schulze and Woodward conclude that three factors contributed to this third peak. The first was a wage explosion as the social contract broke down, culminating in the ‘winter of discontent’ in 1978–9. Another factor was the second oil shock in 1979 (OPEC 2), which was less spectacular than OPEC 1, but led to crude petroleum prices to rise by 126 per cent between 1978 and 1980. The third factor was the increase in indirect taxation in 1979 and the reduction in the standard rate of tax from 33 per cent to 30 per cent.

For critics of British monetary policy for the 1950s through to 1979, the fact that there had been little reliance on monetary policy lay at the door of the Radcliffe Committee (Radcliffe Report 1959) with its ‘uncritical acceptance of neo-Keynesianism as a theoretical basis for monetary policy’ (Walters Reference Walters, Croome and Johnson1970, p. 40). As David Laidler (Reference Laidler1989, p. 1149) remarked, for Keynesians ‘monetary policy, if it matters at all, matters mainly for real income and employment, not prices’. In the wake of the report, the ‘voices in support of the control of money supply were few and, when heard, quietly ignored or put down’ (Capie Reference Capie2010, p. 450) and its influence extended beyond government circles to an ‘economic establishment that seemed to believe that inflation was always and everywhere a real phenomenon’ (King Reference King2000).

For monetary economists, accounting for inflation in the 1970s had little to do with negative supply-side shocks (OPEC 1 and 2) or sociological explanations (e.g. trade unions). The world money supply had grown rapidly in 1971–2 and in 1977–8 (i.e. before OPEC 1 and 2) at between 10 and 13 per cent per year (McKinnon Reference Mckinnon1982, p. 322). Darby and Lothian (Reference Darby and Lothian1983) and Barsky and Kilian (Reference Barsky, Kilian, Bernanke and Rogoff2002) have argued that these expansionary monetary policies in the US and other countries, amplified by the international monetary system, led to higher inflation and to increases in world commodity prices, including the price of oil. These arguments echo the work of Milton Friedman who, writing in the mid 1970s, took aim at those who confused changes in relative prices with changes in absolute prices:

Why should the average level of all prices be affected significantly by changes in the prices of some things relative to others? Thanks to delays in adjustment, the rapid rises in oil and food prices may have temporarily raised the rate of inflation somewhat. In the main, however, they have been convenient excuses for besieged government officials and harried journalists rather than reasons for the price explosion. (Friedman Reference Friedman and Friedman1975, pp. 114–15)

As monetarists argued, even if a government was pursuing a constant money growth rule, a major supply-side disturbance would reduce potential output permanently. That would mean that the level of prices consistent with any level of money stock would be higher, permanently. Monetary policy could not reverse a negative supply-side shock such as OPEC 1, but if it were to accommodate it through an expansionary monetary policy, then inflation would take hold (Cagan Reference Cagan1979, p. 193).

Monetarists were equally dismissive of sociological explanations for inflation. They argued that expansive monetary policies generated excess demand and with the accompanying rise in inflation, trade unions and firms pushed up nominal wages to obtain an increase in real wages. The actual rate of inflation is determined by excess demand and the expected rate of inflation. Rising unemployment and accelerating inflation follows and because of disequilibrium inflation (the actual rate of inflation is higher than expected rates), any real value of money income increases would be eroded by increasing prices at a faster rate than anticipated. As trade unions sought to realise real income increases due to unanticipated inflation, social unrest rose. Industrial unrest is a consequence not a cause of inflation (Laidler Reference Laidler, Johnson and Nobay1971, Reference Laidler1974; Ward and Zis Reference Ward and Zis1974; Zis Reference Zis1975).

Edward Nelson's work draws on the work of the monetarists in the formulation of his monetary policy neglect thesis, which he illustrates through a standard new Keynesian Phillips curve (Nelson Reference Nelson2005). Using this, he shows that high rates of inflation in the 1970s were the result of positive output gaps, produced by an over-expansionary monetary policy, and nonmonetary or ‘cost-push’ events did not exercise any independent effect on the mean of inflation. He notes that whilst the authorities accepted that economic output above potential contributed to inflation and were willing to tighten demand if they felt the output gap was positive, it was usually the case that the authorities believed the output gap was negative. Moreover, whilst the authorities in the 1950s and 1960s believed that aggregate demand was insensitive to monetary policy actions, by the 1970s they viewed monetary actions as ineffective in controlling inflation, not aggregate demand (Nelson and Nikolov Reference Nelson and Nikolov2004). In their nonmonetary framework, the authorities viewed output below potential as something that made inflation worse, via a unit-cost-push channel, rather than a disinflationary tool (Batini and Nelson Reference Batini and Nelson2009, p. 27), and macroeconomic policy was used in a counterproductive way (e.g. tax cuts and interest-rate cuts were viewed as anti-inflation measures) as policymakers attempted to close the output gap. The inflation outcomes of the 1970s were thus a combination of monetary policy neglect and the mismeasurement of the degree of excess demand in the economy.

Needham (Reference Needham2014, p. 10) agrees that there is merit in Nelson's argument that policymakers miscalculated the difference between potential GDP and actual GDP, especially after the first oil shock in 1973 when capital equipment predicated on cheap oil became obsolete. Economists have long argued that the mismeasurement of the output gap as an excuse for poor policy decisions cannot be substantiated (Laidler Reference Laidler1978; Nelson Reference Nelson, Mahadeva and Sinclair2002) and Nelson and Nikolov (Reference Nelson and Nikolov2004, p. 314) conclude that a weakness of the output gap mismeasurement story is that it does not seem to account for the quantitative magnitude of UK inflation in the 1970s. Indeed, Nelson (Reference Nelson2022, p. 15) has gone further and remarked that the UK policymakers’ framework surrounding inflation analysis and control in the 1970s ‘was fundamentally misconceived and would have given rise to serious errors even in conditions of accurate gap measurement’.

The rest of the article now turns to consider the specific policy decisions made by the authorities to determine the extent to which a monetary or nonmonetary view of inflation held until the end of the 1970s. The next section considers the period from 1967 to the mid 1970s.

III

The story of monetary policy in the 1970s begins shortly after the devaluation of sterling in November 1967 when the Bank and Treasury held detailed discussions with the IMF.Footnote 2 The IMF had been unimpressed with the ability of the UK authorities to control monetary growth prior to the devaluation and convened a seminar in October 1968 where they suggested there should be a new emphasis on monetary policy. The seminar was uncomfortable for the majority of the UK officials, not least because they were uneasy about accepting sharper and higher movements in interest rates as a trade-off for greater control of the money supply.Footnote 3 Although the authorities initially prevaricated on a number of issues, chiefly whether the IMF's preferred definition of the money stock in an open economy − Domestic Credit Expansion (DCE) − could be applied to the UK, they did acknowledge that they had paid too little attention to monetary policy after 1945 and needed to adopt a clearer position on the money supply.Footnote 4

Chancellor Roy Jenkins published a letter of intent to the IMF stating that he intended to keep the expansion of DCE within a figure of £400 million in 1969/70 and in his April 1970 Budget, he set a £900 million limit on the growth of DCE for 1970/71. This was not a target for the money supply, although some commentators took this to mean that the Bank of England was assuming a specific money supply target (Economist 1970a; Tew Reference Tew and Blackaby1979, pp. 247–8; Batini and Nelson Reference Batini and Nelson2009). Additionally, the imposition of a ceiling for DCE did not imply a rejection of Keynesian-inspired approaches to economic management and a nonmonetary approach to inflation still held (Clift and Tomlinson Reference Clift and Tomlinson2012, p. 495).

As Needham (Reference Needham2014, p. 18) notes, the Conservative government of Edward Heath, which took office in June 1970, had clearly not undergone the same ‘theoretical journey’ as the Bank and the Treasury with regards to monetary policy and the more ‘resolute and scientific grip’ (Economist 1970b, p. 14) which it was hoped would be exercised on the money supply never materialised. Instead, in the two years after October 1971, the broad monetary aggregate (M3) grew by over 60 per cent. The increase during the first nine months was caused by the growth in bank lending; thereafter it was the rise in the public sector deficit which was the main cause, with only a third of the debt being sold to the non-bank private sector (in other words, the government was borrowing from the banking system). The consequences were asset price inflation, mainly in residential and commercial property; an enormous increase in real domestic demand in 1973 to 7.8 per cent; and an increase in inflation after a long and variable time lag, to over 25 per cent in 1975 (Pepper Reference Pepper1998, p. 135; Congdon Reference Congdon2005, pp. 59–64).

Heath refused to allow Bank Rate to rise to choke off broad money growth and Needham (Reference Needham2014, p. 47) suggests this was because Heath never fully understood that Competition and Credit Control (CCC), which had been introduced in September 1971, was ostensibly about controlling the money supply by varying interest rates. Yet even if this was the case, Heath did not believe inflation was a monetary phenomenon and took the view that it was caused by nonmonetary factors, primarily wage increases. Heath was ‘a Keynesian by instinct and by intellectual conviction’ (Denham and Garnett Reference Denham and Garnett2001, p. 245) and believed an expansionary monetary policy was anti-inflationary as it added to total output (Heath Reference Heath1998, p. 405). It is thus ironic that halfway through the explosion in broad money growth, the director of the Central Policy Review Staff (the unit in the Cabinet Office responsible for developing long-term strategy and co-ordinating policy across government departments) commented on a paper described as ‘a child's guide to the money supply’ that the Prime Minister, the Chancellor and Treasury ministers are ‘specialists on the subject and would already know everything included in this note’.Footnote 5 To attribute the failure of monetary control solely to Heath's government, however, is to ignore the actions of the Treasury and Bank.

As Brendon Sewill, a special adviser to the Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1970 and 1974, remarked:

I found that the Treasury was 100 per cent Keynesian and remained 100 per cent Keynesian … During my time at the Treasury from 1970 to 1974, I never heard any suggestion that the economic problems could be solved by controlling the money supply. It needed to be kept tight, but that was not a determinate. I remember Tony Barber saying that Nick Ridley, a back bencher, had cornered him in the Lobby and said that he ought to do something about monetarism and asked him what monetarism was. He asked me what to do about it. We said for him to put a paper to the Treasury. The answer came back from the Treasury officials, Mr Downey [Head of Central Unit, Treasury, 1975] and endorsed by the Permanent Secretary, that monetary policy was there to support the Budget judgment and the fiscal balance, and it only had a very subsidiary role to play.Footnote 6

Evidence from the archives supports Sewill's remarks. The briefing paper by the Treasury on monetary policy for the incoming government in June 1970 made clear that the new emphasis on money post-devaluation ‘did not represent a conversion to Friedmanism, or indeed any greater degree of certainty as to the nature of the relationships between monetary changes and changes in the main components of national income and expenditure’.Footnote 7 At the outset of the 1970s, there were misgivings expressed about the use of money supply targets, even down to semantics.Footnote 8 Treasury officials had a a list of objections to having targets for internal use, which included not fully understanding the causal relationships between the real economy and the monetary system; ‘ignorance’ about knowing what the optimum growth of the money supply should be and where the target should be set and the impracticalities associated with ‘fine tuning’ the money supply.Footnote 9

The explosion of broad money growth after 1971 led to growing criticism of the economic policy from outside government. In European circles there was disquiet that the British government had not taken more stringent measures to check the growth in public expenditure and to control the growth of the money supply, but the Treasury dismissed European thinking on a money-supply target as ‘pretty primitive’.Footnote 10 A group of economists wrote to Heath in September 1973 arguing that excessive growth of the money supply had caused inflation, which stemmed from public expenditure financed by borrowing from the banking sector, and the net borrowing requirement should be limited to what could be borrowed from the non-bank private sector. The reply to the letter by John Nott, Minister of State, was mere lip service: ‘monetary control is a vital part of any counter-inflation strategy, I would not agree that limitation of the growth of the money supply itself could cure inflation here in current circumstances without grave economic disruption including high unemployment’.Footnote 11 A comment by Adam Ridley (later a special adviser to Geoffrey Howe and Nigel Lawson) on a paper written by Alan Walters, which was highly critical of the direction of monetary policy, downplayed the role of the money supply as a weapon for controlling inflation as the Heath government's focus was on prices and incomes policies.Footnote 12 Walters, who was Heath's economic adviser, resigned two months later in frustration with the conduct of monetary policy.

The archives provide a clear picture that the Treasury was unaware of the causes of growth in M3 and continuing to express the view that money-supply targets were difficult to implement and to publish. Generally, the Treasury was slow to accept that there might be an argument for expressing a money-supply target as a percentage of annual growth, and was even more reluctant to tie this to a specific time period. As Sir Douglas Wass (Reference Wass2008, p. 64), the permanent secretary to the Treasury in 1973, noted, monetary aggregates were seen as indicators of liquidity in the economy rather than signals which would prompt monetary action. Although they admitted that they were ‘embarrassed’ by the growth of M3, and the very big rise in bank lending to the private sector, Nott suggested to Treasury officials that ‘the more we can play down the importance of M3 and emphasise its fickle nature, as the Bank of England have been doing, the better. I cannot really envisage the M3 figures being a help to us.’Footnote 13

The Bank's views on monetary policy between 1967 and 1974 are more opaque. There were differing views internally about the role of the money supply in the wake of the 1967 devaluation and following the formation of the Money Supply Group in December 1968, a period of serious monetary research in the Bank which drew on theoretical work in academia (Needham Reference Needham2014, pp. 26–7; Goodhart and Needham Reference Goodhart and Needham2017, p. 352). The Bank had been unequivocal in its advice to the Chancellor as early as October 1970 that if the rates of growth of the money supply and DCE were to be slowed, then bank lending needed to be lower or additional gilt-edged stock needed to be sold to the non-bank public.Footnote 14 As Needham has attested, the Bank had been frustrated in its dealings with the Heath government and it considered the monetary aggregates seriously during this period. However, despite the work of the Money Supply Group and the Bank's internal discussions about the role of money, the deputy governor, Jasper Hollom, was clear. In a public speech in 1973, Hollom expressed the view that: ‘in the circumstances of today some form of incomes policy has a part to play in the control of inflation’ (Bank of England 1973, p. 201). The nonmonetary approach to inflation still dominated the Bank's thought processes.

Both Capie (Reference Capie2010, pp. 645–8) and Needham are critical of the Bank during the operation of CCC, noting that it simply could not calculate how much of the growth in M3 was due to the process known as ‘reintermediation’ (lending by the ‘fringe’ banks prior to September 1971 which returned to be counted in the monetary statistics) and how much was generated by ‘round tripping’ (where borrowers could draw on their unused overdraft facilities and then redeposit the proceeds at higher rates in the wholesale market). As the Thatcher government discovered in the early 1980s, trying to hit a money-supply target in a statistical fog when changes were occurring in the financial system was very difficult to do.

CCC was effectively ended in December 1973 when quantitative controls were reintroduced through the supplementary special deposits scheme (SSDS), which involved a shift from trying to control bank assets to controlling their interest-bearing eligible deposit liabilities (IBELs). The intention of the SSDS was to replace interest rates with another monetary instrument to control the growth of the money supply, but this was entirely superficial. Banks were penalised if their IBELs grew by more than a certain amount. The scheme was easy to circumvent because Certificates of Deposit, which were within the definition of the aggregate being targeted, M3, could be swapped for guaranteed commercial bills, which were outside the definition.Footnote 15 The main effect of the scheme was to distort the data for M3 downward. The SSDS was nicknamed ‘the corset’, which, as the influential Financial Times columnist Anthony Harris wrote at the time, was most appropriate because a corset is a device for producing deceptive figures.Footnote 16

IV

Despite the experiments of the early 1970s, the monetary authorities continued to hold the view that monetary policy should not be used to control inflation. As Needham acknowledges, monetary policy had become predominantly a technical exercise in maintaining orderly markets, and dealing with the effects of the Secondary Banking Crisis, so by the mid 1970s:

The authorities viewed inflation as primarily a wage-push phenomenon. It therefore made sense to combat record inflation by pressing down on incomes. Monetary policy and monetary targets were adjuncts to incomes policy. (Needham Reference Needham2014, p. 107)

Senior Treasury officials pressed the Chancellor for a more rigorous approach to wage restraint at the end of 1974 and a new economic strategy.Footnote 17 In the Bank, Sir Kit McMahon, an executive director, was unequivocal: ‘it will only be possible to contain inflation in late twentieth century democratic industrial societies with the aid of more or less continuous incomes policies based broadly on consent’ (Capie Reference Capie2010, p. 653).

Discussions inside the Bank and Treasury about what role monetary policy should play in economic management continued to move slowly in 1975. Three months after the rate of inflation had reached 25 per cent in June 1975, Dow began a basic conversation within the Bank on what he believed monetary policy to be and how it worked (Capie Reference Capie2010, p. 653). The official papers for this period concur with Wass's observation on the Treasury discussions with the Bank that both sets of officials ‘did not seem greatly exercised about the use of monetary policy, or lack of it’ (Wass Reference Wass2008, p. 138).Footnote 18 In October 1975, the Treasury were persuaded to join the Bank in a working group (entitled the Bridgeman Working Group) to examine monetary policy and when it reported in December 1975 they made it clear that:

The Working Party does not accept the monetarists’ view that M1, M3 or any other single monetary indicator is itself of overriding importance, or that macro-economic management should be conducted in accordance with their prescriptions.

It reaffirmed the belief that ‘monetary policy should not be the main instrument in either demand management or controlling inflation’ but in a strange twist, the report conceded that there were long and variable lags between the growth of the money supply and inflation. It was for this reason that ‘it seems safer to assume that the risks to monetary policy being destabilising will be minimised if the money stock is held to a fairly smooth path from year to year’.Footnote 19 This admission did not lead to a Damascene conversion to a Friedman constant money growth rule.

Wass quickly played up the disagreements between the Bank and the Treasury following a meeting to discuss the report in January 1976, telling the Chancellor in March 1976 that ‘our attempts to reach an agreed analytical position have not exactly been crowned with success’ (Needham Reference Needham2014, p. 93). More fundamentally, as the chair of the working group, Michael Bridgeman, explained in a note about the formulation of monetary policy in the 1976 Budget statement, the thrust of counter-inflation policy remained pay restraint. Action to control the money supply would only be taken if the pay policy was only ‘partly successful’ and any reinforcing monetary action would be used ‘to avoid a collapse of confidence in the financial markets’.Footnote 20

Denis Healey, the Chancellor, publicly announced a target for sterling M3 on 22 July 1976, much to the chagrin of Wass who stated, ‘I think we have come very close to overdoing this targetry business’, and told the principal private secretary to the Chancellor, Nicholas Monck, that his views were shared by the majority of the Treasury.Footnote 21 Needham (Reference Needham2014, p. 172) notes that at this stage, ‘given the Labour government's lack of credibility with financial markets Healey had to pay close attention to his monetary targets’. So how genuine was this attempt by the Labour government to adopt a monetary approach to control inflation?

Healey did not accept a monetary view of inflation and later remarked that the ‘monetarist mumbo-jumbo’ could not be ignored ‘so long as the markets took it seriously’ (Healey Reference Healey1989, p. 434). As Geoffrey Littler, deputy-secretary in charge of the domestic economy sector in the Treasury, attested:

Denis was intellectually very interested in it [monetary targets], but it could hardly be said to have constituted a major feature of the Government's policy. It was a piece in the jigsaw, but there was not a great deal of discussion about it. It did not change very much over the period, whereas pay policy changed almost every day.Footnote 22

Wass concurs, commenting that even though the money supply assumed ‘some importance in 1976’, the shift was ‘not nearly to the extent of accepting the precepts of the monetarists’ (Wass Reference Wass2008, p. 23). Indeed, at the end of December 1976 an early draft of the National Recovery Programme for 1977–81/2 was categorical that that ‘basis of the Government's counter-inflation strategy will continue to be the Social Contract agreement with the trade union movement’.Footnote 23

Following his appearance at a Witness Seminar in 2005, Gordon Pepper, who was a partner at the City firm W. Greenwell and Co. in the 1970s, wrote to McMahon to discuss some of the arguments outlined in Pepper and Oliver (Reference Pepper and Oliver2001) and the reasons why a money-supply target could be adopted for political economy reasons, along the lines suggested by Fforde (Reference Fforde1983). In short, political economy reasons are concerned with the political presentation of a money-supply strategy to a wide variety of audiences. McMahon's reply was unequivocal: ‘My reasons for supporting a publicly announced money supply target in mid-1976 were very much on the lines you set out. Neither Dow, Fforde nor I believed at all in Friedmanian monetarism.’Footnote 24 Wass (Reference Wass2008, p. 23) is scornful of the governor's claim in 1978 that he was a practical monetarist, noting this ‘hardly qualified as a commitment to an attempt to secure the rigid control of the money supply’.

One of the reasons why the senior Bank officials supported monetary targets in the mid 1970s was to exercise greater control on the Public Sector Borrowing Requirement (PSBR), and a publicly announced target would provide ‘a tighter rope round the Chancellor's neck’.Footnote 25 The link between the PSBR and the money supply is through the credit counterparts approach, which was favoured by those who supported broad money (sterling M3) targets. Healey's letter of conditionality to the IMF in December 1976 acknowledged the connection between reducing the PSBR and hitting the money supply target, which in so doing would ‘establish monetary conditions which will help the growth of output and the control of inflation’.Footnote 26

Nelson (Reference Nelson2005, pp. 35–6) has acknowledged that the UK moved away briefly from the nonmonetary views of inflation in 1976–7 but reverted to nonmonetary views in 1977. Given what has been discussed above, it is clear why this move was fleeting. The government continued to rely on prices and incomes policies (and increased government expenditure between 1977 and 1979) and quantitative regulations (the ‘corset’) to control monetary growth, which was an approach steeped in the nonmonetary view of inflation (Allsopp Reference Allsopp, Artis and Cobham1991, p. 23; Nelson and Nikolov Reference Nelson and Nikolov2004, p. 308 Capie Reference Capie2010, p. 687). Whilst the authorities chose to pursue money supply targets over the exchange rate in autumn 1977, the 1977/78 target for sterling M3 was overshot by 3 per cent, which suggested that they were not acting decisively enough (Cobham Reference Cobham, Artis and Cobham1991, p. 51). Indeed, following an IMF seminar in the Bank in May 1977, two members of the IMF team told a Bank official that although publicly announced targets were in place, the Bank seemed to have done little or nothing to ensure that they were met. As Capie (Reference Capie2010, p. 703) has commented, it is difficult to ascertain what the Bank's views on monetary control were, and ‘at times, it is hard to tell where confusion left off and wilful misunderstanding took over’.

V

Writing in the mid 1970s, Williamson and Wood (Reference Williamson and Wood1976, p. 529) commented that the UK's inflation performance post-1967 was generally not ‘primarily attributable to economic illiteracy on the part of the authorities’ even if the ‘undoubted truth’ was that the authorities underestimated the long-run importance of monetary factors. In considering the economic decision-making process of the 1970s it is important to remember that the senior policymakers and politicians of that decade had cut their teeth in an era that saw monetary policy as essentially antediluvian.

Following the 1967 devaluation, Bank and Treasury officials were initially resistant to reconsidering the role of monetary policy yet came to realise that some monetary discipline was needed to replace the nominal anchor provided by Bretton Woods. Several experiments were undertaken with monetary policy from the early 1970s and Duncan Needham makes a strong case that the authorities were not passive in their approach to monetary developments as they had been prior to the devaluation of 1967. Nevertheless, despite the experiments with monetary policy, a monetary boom was allowed to go unchecked and there was a strong attachment to nonmonetary measures to control inflation, so that by the mid 1970s monetary policy still played second fiddle to incomes policy.

Even though the authorities were implementing nonmonetary measures to control inflation, they did begin to consider the monetary approach from the early 1970s, which became more serious as the decade wore on. This is given insufficient weight in Edward Nelson's work and the intellectual development in the Treasury's thinking was not covered in Capie's history of the Bank. The Bridgeman Report, which had considered the monetarist arguments, concluded in December 1975 that monetary policy should not be the main instrument in either demand management or controlling inflation but within seven months the Labour government had adopted monetary targets. Even if policymakers had become less neglectful of monetary policy by the second half of the 1970s, the adoption of a monetary target in 1976 was superficial and undertaken only to gain credibility with the financial markets and the IMF. In short, this article confirms the work of Nelson and his co-authors that the authorities ascribed to a nonmonetary view of inflation during the 1970s.

Finally, as Ben Broadbent, the Bank's deputy governor in charge of monetary policy between 2014 and 2024, has observed, it is little wonder that the UK's inflation performance during the 1970s was so poor compared to other countries, particularly as policymakers believed that neither inflation expectations nor the output gap seemed to matter. In short, ‘monetary policy didn't really have a material part to play in either explaining or controlling inflation’ (Broadbent Reference Broadbent2020, p. 12). All of this contrasts with the Thatcher government elected in May 1979, who were explicit about their chosen means of bringing down inflation:

Inflation can only be reduced in the long run through control over its underlying causes. This means not an incomes policy – which only deals with one symptom of the disease – but control of the money supply [emphasis in original].Footnote 27

The difficulties which the authorities had in achieving money-supply targets during the 1980s and the growing ‘monetarist neglect’ during that decade is part of another story. Nevertheless, 50 years on from the UK's highest every peacetime inflation, the view that monetary policy is responsible for the control of inflation, not administrative, industrial and tax measures aimed at directly affecting prices and costs, is widely held by economists, officials and politicians.