Eating disorders are associated with a high risk of mortality and high illness burden, including major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, heart failure, musculoskeletal and renal complications.Reference de Oliveira, Colton, Cheng, Olmsted and Kurdyak1–Reference Mitchell and Crow4 One meta-analysis reported an overall elevated mortality rate for eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified, EDNOS), which in some instances was much higher than for other psychiatric disorders.Reference Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales and Nielsen5 Eating disorders have also been associated with high healthcare costs, related to both psychiatric and non-psychiatric hospital admissions. Previous research has found that direct healthcare costs for individuals admitted for an eating disorder in Ontario, Canada, in 2012 were about Can$48 million, with higher costs for those under the age of 20 and those 65 and older.Reference de Oliveira, Colton, Cheng, Olmsted and Kurdyak1 However, few population-based surveillance studies estimating incidence, prevalence and mortality in eating disorders have been published,Reference Hudson, Hiripi, Pope and Kessler2,Reference Udo and Grilo6,Reference Smink, van Hoeken, Donker, Susser, Oldehinkel and Hoek7 with the literature on the epidemiology and outcomes of eating disorders having significant limitations, such as small samples and few large-scale mental health surveillance studies.Reference Hudson, Hiripi, Pope and Kessler2,Reference Udo and Grilo6

Most of the literature reporting on mortality among people with eating disorders comes from studies examining cohorts in specific treatment settings, which are difficult to compare, given the wide variability in treatment target populations, insurance coverage and other selection biases.Reference Keshaviah, Edkins, Hastings, Krishna, Franko and Herzog8,Reference Smink, van Hoeken and Hoek9 Several mortality studies report only crude case fatality rates (i.e. they report on deaths among patients with no comparison group or adjustment for expected mortality in the same age population); other studies are limited in sample size or scope and report only on anorexia nervosa and/or only examine female patients.Reference Smink, van Hoeken and Hoek9,Reference Keel, Dorer, Eddy, Franko, Charatan and Herzog10 Eating disorders have been misperceived as rare, perhaps owing to limited awareness of the available data on the burden of disease or a misconception that only the most severe cases experience a severe burden.Reference Simon, Schmidt and Pilling11,Reference Striegel-Moore12 Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive data that include both males and females has made it difficult to estimate all-cause and cause-specific mortality in this population.

This study describes all-cause mortality rates in a population-based cohort of patients with an eating disorder in the context of universal public healthcare funding. Excess mortality among these individuals was estimated relative to the general population without an eating disorder using standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) and potential years of life lost (PYLL) (in total and attributable to eating disorders). In addition, factors associated with increased hazard of mortality in the cohort were examined, including sociodemographic and comorbidity measures as well as indicators of healthcare service use.

Method

Study design

This study examines a population-based retrospective cohort of individuals who received care for an eating disorder in any hospital in Ontario between 1 January 1990 and 31 December 2013. The cohort was followed, through record linkage, until date of death or 31 December 2013, the latest date possible based on data availability at the time of the analysis.

Data sources

We made use of administrative healthcare data available through ICES in Toronto, Ontario. ICES is an independent non-profit organisation funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and it holds an inventory of coded and linkable health data-sets, encompassing much of the publicly funded administrative health services records for the Ontario population eligible for universal health coverage since 1986. This data repository includes individual-level, linkable longitudinal data on most publicly funded healthcare services. The Registered Persons Database (RPDB), a population-based registry, contains anonymised demographic data on all insured members of the universal Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP), such as gender, date of birth, urban or rural dwelling information and neighbourhood-level income (measured in quintiles at the census tract level). Information on date and cause of death (where applicable) were obtained from the Ontario Office of the Registrar General, Vital Statistics Agency. Hospital admissions and associated diagnostic codes used to define the cohort were obtained from the following healthcare administrative databases maintained by the Canadian Institute for Health Information: the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) for non-mental health admissions and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS) for emergency department visits. Psychiatric hospital admission records were obtained from the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS) database.

Comorbidity data for chronic medical conditions were obtained via the following validated patient cohorts and registries developed, linked and analysed at ICES: Ontario Congestive Heart Failure Database; Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Database; Ontario Diabetes Database; Ontario Asthma Database; Ontario HIV Database; and Ontario Cancer Registry. These data-sets have been described elsewhere.Reference Davies, Iwajomo, de Oliveira, Versloot, Reid and Kurdyak13

Derivation of the cohort

Individuals were included if they had received an eating disorder diagnosis during an emergency department visit, medical hospital admission or psychiatric hospital admission between 1990 and 2013. The first diagnosis from any of these data sources was determined as the cohort entry date. Cohort development and analyses were carried out with linked administrative healthcare data holdings at ICES. The diagnostic codes used to identify eating disorder were: ICD-9 codes 307.1 (anorexia nervosa), 307.51 (bulimia nervosa), 307.50 (eating disorders not otherwise specified, EDNOS); ICD-10 codes F50.0 (eating disorders), F50.1 (anorexia nervosa), F50.2, F50.3 (bulimia nervosa), F50.8, F50.9 (EDNOS); and DSM-IV codes 307.1 (anorexia nervosa), 307.51 (bulimia nervosa), 307.50 (EDNOS). We restricted our study to these three eating disorder diagnoses because the publicly funded services in Ontario focus on the treatment of these three. Eating disorder diagnosis codes do not apply to children under the age of 5. Furthermore, children aged 5 to 9 were excluded as the small number of deaths precluded reporting under Ontario privacy regulations. We excluded individuals who had ceased to be publicly insured for healthcare at date of cohort entry. This approach resulted in a cohort of 19 041 individuals with an eating disorder diagnosis (including all patients deceased or alive to the end of 31 December 2013).

The development of this cohort, restricted to individuals alive as of 1 January 2014, has also been described elsewhere.Reference Kurdyak, de Oliveira, Iwajomo, Bondy, Trottier and Colton14

Analysis

Mortality rates were estimated for the full cohort and were reported as deaths per 1000 person-years of observation time, overall and by gender (female and male), calendar year (from 1990 to 2013) and age group. Person-years of follow-up were segregated by gender, calendar year and age attained over follow-up (to end of follow-up or death) for each cohort member. This was achieved using Lexis expansion tools for cohort data using Stata 14 on Windows. Excess mortality in the eating disorder population, relative to the underlying Ontario population, was illustrated in several ways, including SMRs, PYLL in the cohort, and proportion of PYLL attributable to eating disorder.

SMRs were estimated using the indirect method.Reference Breslow and Day15 SMRs were defined as the number of observed deaths in the cohort divided by the number of expected deaths in the cohort if it had had the same gender- and age-specific mortality experience as the underlying Ontario population. Expected mortality rates in the general population were obtained using all Ontario deaths in 2011 and corresponding data for the 2011 census year. SMRs were presented with exact Poisson-based 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Person-years of life lost (PYLL) for the cohort were estimated as the sum of all years of life lost before 75 years of age16 for observed deaths in our cohort (expressed as PYLL per 1000 persons). Expected and excess (attributable to an eating disorder) PYLL values were also estimated using expected deaths from Ontario 2011 standard mortality rates. The theoretical percentage of total PYLL attributable to being in the eating disorder cohort (relative to the underlying population) was defined as attributable PYLL = (total cohort PYLL – expected PYLL)/total cohort PYLL and expressed as a percentage.

Sociodemographic factors associated with higher risk of mortality within the cohort were examined using Cox proportional hazard regression models for all-cause mortality. Individuals who entered the cohort with an eating disorder diagnosis on the same day as death contributed no follow-up time and were excluded from the survival models (n = 5). Separate Cox models were estimated for individuals aged 10–44 at entry and those 45 and older. Sociodemographic characteristics considered were age, gender and calendar year over the period of the study, as well as neighbourhood-level household income quintile and rurality of residence. Models examining the effect of sociodemographic variables were then further adjusted for medical comorbidity (i.e. chronic conditions, defined beforehand). The adjusted models included six chronic conditions derived from validated cohorts through administrative databases.

Model diagnostics were performed and indicated no violations of assumptions. This included confirmation of the validity of a linear effect of age as a continuous covariate in the exponential Cox model, assessment for non-violation of the assumption of proportional hazards, and lack of excess multicollinearity.

Ethics and approvals

ICES is an independent non-profit research institute whose legal status under Ontario's health information privacy law allows it to collect and analyse healthcare and demographic data, without consent, for health system evaluation and improvement. Thus, the use of data in this project was authorised under section 45 of Ontario's Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require review by a research ethics board. The project was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University Health Network, Toronto.

Results

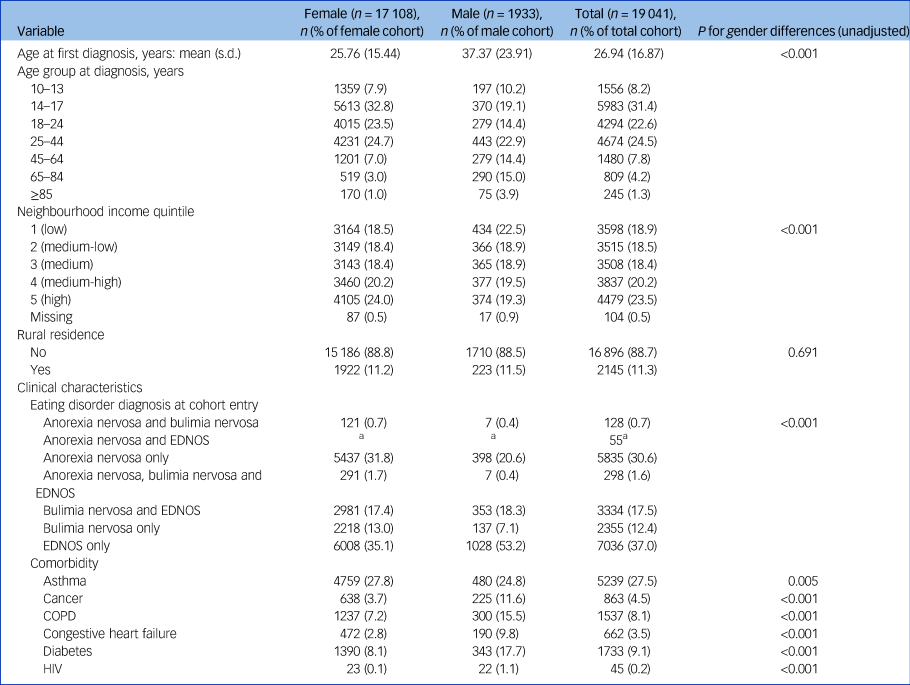

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort are presented in Table 1. Of the 19 041 cohort members, 17 108 were female (89.9%) and 1933 were male (10.1%). Age at cohort entry ranged from 10 to over 85 years, but 88.9% of the population entered the cohort between the ages of 14 and 44. Most of the cohort (88.7%) resided in urban centres. A greater percentage of the cohort lived in middle- to low-income neighbourhoods, with 37.4% in the two lowest neighbourhood-level income categories and 18.4% in the medium neighbourhood-level income category. Categories for eating disorder-specific diagnoses at cohort entry revealed multiple diagnoses for the same individual over time; 32.9% of the cohort had anorexia nervosa alone or in combination with bulimia nervosa and/or eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS); 37.1% of the cohort had a diagnosis of EDNOS alone at enrolment. Eating disorder diagnoses were also comorbid with other medical conditions, including asthma (27.5%), diabetes (9.1%), cancer (4.5%) and congestive heart failure (3.5%).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the eating disorder cohort

EDNOS, eating disorder not otherwise specified; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

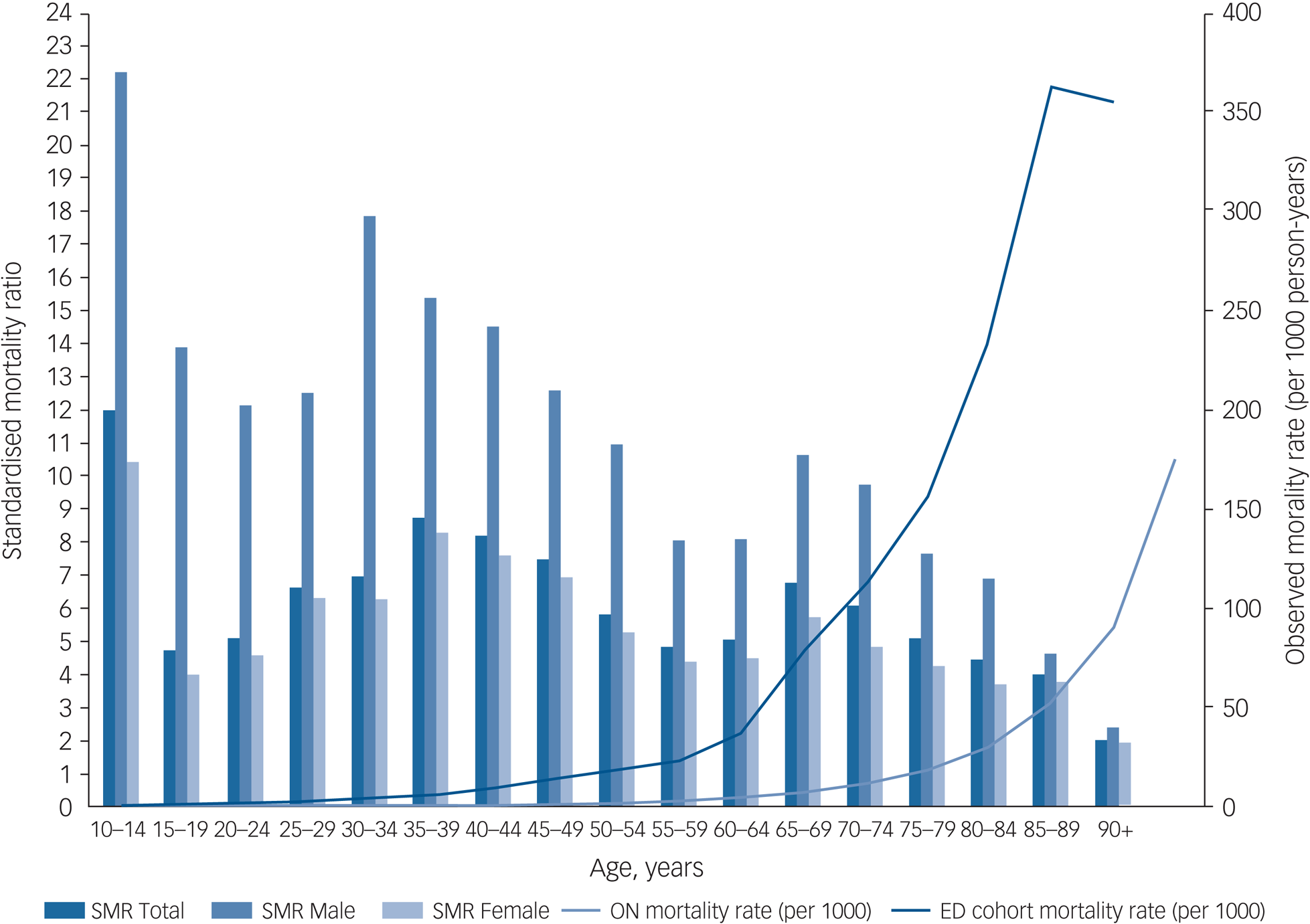

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the mortality follow-up analysis of the cohort, including total person-years of follow-up and observed deaths, for the whole cohort and by age group and gender. Mortality rates and SMRs by age group and gender are also presented in Table 2. For the entire cohort and across all age groups, the all-cause mortality rate was five times higher than expected based on mortality rates in the Ontario population (marginal SMR = 5.06; 95% CI 4.82–5.30). Peak values for SMRs were observed among adults between approximately 30 and 44 years of age. Mortality rates and SMRs were unstable for individuals aged between 10 and 14 owing to the small number of deaths. SMRs were higher for males relative to females, overall and in all age groups. For females, the marginal SMR was 4.59 (95% CI 4.34–4.85) whereas for males it was 7.24 (95% CI 6.58–7.96). Excess mortality is further illustrated in Fig. 1, which presents cohort and population mortality rates (per 1000 population) by age and gender as well as SMRs by gender within age categories.

Table 2 All-cause mortality comparing the eating disorder cohort with the Ontario population overall and by gendera

SMR, standardised mortality ratio.

a. SMRs are stratified by age group, where age is a time-dependent covariate reflecting age attained during follow-up as opposed to age at baseline. Time-dependent age was calculated using the STATA command STSPLIT.

Fig. 1 Standardised mortality ratios by gender and age group, all-cause mortality rates observed in the eating disorders cohort (1991–2013), and mortality rates for Ontario (2011). SMR, standardised mortality ratio; ON, Ontario; ED, eating disorder.

The overall expected PYLL (based on expected numbers of deaths in the cohort using the 2011 Ontario age-specific death rates) was estimated at 29.54 years per 1000 population (95% CI 28.7–30.4) and was similar for each gender separately (supplementary Table 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.197). Within the cohort, estimated total PYLL before age 75 equalled 191.6 per 1000 population (95% CI 189.4–193.8) for both genders combined. Years of life lost per 1000 population was higher for males (within-cohort PYLL = 375.6; 95% CI 364.7–386.8) relative to females (within-cohort PYLL = 174.1; 95% CI 171.9–176.3). For both genders, the excess PYLL attributable to experiencing an eating disorder was 84%. For females, it was estimated that 83% of PYLL were attributable to being in the eating disorder cohort; for males, this value was 92%. Among all people with eating disorders throughout Ontario over the period of this study, it was estimated that 24 773 years of life were lost due to eating disorder, before the age of 75.

Cox survival models on all-cause mortality, controlling for the effects of demographic characteristics, appear in Table 3. For both age groups (10–44 and ≥45 years of age), older age (as a continuous linear term) and male gender were associated with statistically significant increased mortality risk, reflected as adjusted hazard ratios of 1.05 and 1.91, respectively. Additionally, mortality declined over calendar years in the analysis, showing a statistically significant effect of calendar year on the downward trend in mortality over time (adjusted hazard ratio of 0.91, year over year). In addition, the pattern of association with household income quintile was not a simple linear association, but rather a U-shaped curve. Higher total mortality hazard ratios were observed in the highest and lowest income quintiles, relative to income quintiles in the middle.

Table 3 Predictors of relative excess mortality from Cox survival models for all-cause mortality in the eating disorder cohort

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

a. The likelihood ratio test for removal of covariates from the fully adjusted model is shown.

b. Age is defined as a time-dependent covariate, meaning the age the cohort member attained over follow-up and not age at baseline. Time-dependent age was calculated using the STATA command STSPLIT.

Fully adjusted models for age, gender and calendar year resulted in opposite findings for rurality in the analyses for cohort members under and over 45 years of age. Rural residence was associated with lower mortality risk for cohort members under the age of 45 but higher mortality risk for cohort members 45 or older. Among cohort members aged 45 and over, control variables for non-eating disorder chronic medical conditions (congestive heart failure, COPD, cancer and HIV) were all positively associated with higher mortality ratios, with the exceptions of inverse associations for asthma and diabetes diagnoses. For cohort members aged 44 and younger, having a diagnosis of congestive heart failure, cancer, diabetes or HIV was positively associated with higher mortality ratios. We observed a simple linear trend towards lower mortality with calendar year of entry into the cohort. This cannot be separated from a general trend in improved survival in the population, as age- and gender-specific mortality risk expected in the population is not updated for each calendar year but based on census years (here, based on the 2011 Canadian census).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to estimate the excess mortality and burden associated with eating disorders using comprehensive population-based data. Notably, this study is among the few internationally to have made use of a population-based eating disorder cohort and to have provided SMR estimates specific to both female and male patients. Our findings show that individuals with eating disorders diagnosed in hospital settings had a mortality rate five-fold higher than the general population, with more than 80% of life lost before the age of 75 for both females and males.

In females with eating disorders, we found a roughly five-fold higher mortality rate relative to the general population. This is similar in magnitude to what has been reported in two international meta-analysesReference Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales and Nielsen5,Reference Keshaviah, Edkins, Hastings, Krishna, Franko and Herzog8 and similar in magnitude to SMRs reported specifically for anorexia nervosa (anorexia nervosa being the eating disorder diagnosis with the highest SMRs).

Although studies have reported that the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders among males ranges from 0.1 to 2.0 for all types,Reference Hudson, Hiripi, Pope and Kessler2,Reference Smink, van Hoeken and Hoek9 few studies have reported on the mortality rates among males with eating disorders and those studies tend to report exclusively on anorexia nervosa.Reference Kask, Ramklint, Kolia, Panagiotakos, Ekbom and Ekselius17,Reference Møller-Madsen, Nystrup and Nielsen18 Our study thus makes a novel and important contribution to the sparse literature on males with eating disorders and their mortality experience, with a substantially larger sample of males. The SMRs observed in males were almost two-fold higher than in females. This observation of higher mortality in males with eating disorders is particularly concerning as there is evidence to suggest that males are less likely to self-identify or be identified with eating disorders unless the illness severity is extremely high. Additionally, eating disorder treatment centres are less likely to accept male patients.Reference Mond, Mitchison, Hay, Cohn and Lemberg19,Reference Murray, Nagata, Griffiths, Calzo, Brown and Mitchison20 Gender and cultural differences in help-seeking behaviours by males with eating disorders may result in services being less accessible, contributing to worse outcomes. This highlights the need for enhanced case identification, research and services for males with eating disorders to improve outcomes.Reference Strother, Lemberg, Stanford and Turberville21

We also found that mortality risk was higher among younger individuals in the cohort and individuals living in the lowest-income neighbourhoods, highlighting problems related to equity of access and quality of care; this warrants further investigation.

Although there have been two meta-analyses estimating eating disorder-related mortality,Reference Arcelus, Mitchell, Wales and Nielsen5,Reference Keshaviah, Edkins, Hastings, Krishna, Franko and Herzog8 the existing literature has methodological problems, including a lack of population-based surveillance data (limited to subregional studies and registries from restricted clinical practicesReference Fichter and Quadflieg3,Reference Pinhas, Morris, Crosby and Katzman22 ), selection of study population, identification of cases and small sample sizes.Reference Smink, van Hoeken and Hoek9,Reference Keel, Dorer, Eddy, Franko, Charatan and Herzog10,Reference Kask, Ramklint, Kolia, Panagiotakos, Ekbom and Ekselius17,Reference Hart, Mitchison and Hay23–Reference Keski-Rahkonen and Mustelin25

Finally, our results demonstrate the degree to which patients diagnosed with eating disorders also experience important medical conditions and comorbidities, such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, COPD and hypertension. Mechanisms by which eating disorders may have a causal impact on diverse chronic diseases have been described elsewhere.Reference Mitchell and Crow4

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of our study was the use of a population-based sample, which is more representative and generalisable than cohorts based on a sample of hospital in-patients from individual treatment centres or insurance programmes. An additional methodological strength was the use of the recommended SMR method, which is replicable and well established, to report excess mortality relative to the underlying population, as well as controlling for gender and age through standardisation (as opposed to merely reporting case-fatality rates within the clinical cohort).

One major limitation is the lack of validation of our algorithm for case detection, which relied on hospital contact data and not out-patient contact data. This may bias towards higher severity of cases and may also truncate the time between illness identification and mortality, which could result in an overestimation of mortality rates.Reference Swanson and Field26 These are limitations of all research involving clinical cohorts based on administrative or insured-services data. These inherent limitations of the best data available underscore how important it is to have disease registries for eating disorders established internationally, with high-quality clinical measures, which are available only in localised clinical research cohorts.Reference Pinhas, Morris, Crosby and Katzman22 Moreover, the lack of data on ethnicity did not allow us to produce ethnicity-specific SMRs; future research should seek to address this limitation. Finally, this study included a specific group of eating disorder diagnoses (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS) for which treatment is available in Ontario's publicly funded system. We did not include other eating disorder diagnoses such as binge eating disorder, and it is unclear whether the findings from our study would generalise to a broader array of eating disorder diagnoses.

Impact and relevance

This study serves to highlight the need for ongoing population-based surveillance of eating disorder burden. Historically, the burden of eating disorders, including mortality, has been documented to a lesser extent compared with the burden of other psychiatric conditions, despite its prevalence and high mortality rate. Early intervention in eating disorders is known to be effectiveReference Arcelus, Bouman and Morgan27,Reference Currin and Schmidt28 and presents an opportunity to reduce the high- and early-onset mortality risk of these conditions. The inclusion of eating disorders among other disorders identified as high priority for improved surveillance and burden of disease data in mental health also highlights a need for better detection and treatment of eating disorders and associated psychiatric comorbidities to improve long-term outcomes. Finally, our finding that males with eating disorders have a higher risk of mortality than females underscores the importance of detecting and treating eating disorders in males even though they are relatively low in prevalence.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.197.

Data availability

The data-set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Although data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data-set publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full data-set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available on request, on the understanding that the computer programs may rely on coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification. Parts of the material presented here are based on data and/or information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). The analyses, results, conclusions, opinions, views and statements expressed in the material are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. Parts of this report are based on Ontario Registrar General (ORG) information on deaths, the original source of which is Service Ontario. The views expressed therein do not necessarily reflect those of ORG or the Ministry of Government Services.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the formulation of the research question and study design. P.K., S.J.B., C.D.O. and T.I. oversaw the data analysis, T.I. analysed the data at ICES. S.J.B. and T.I. drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to review of the manuscript and approve of the final submission.

Funding

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). This study also received funding from the Labatt Family Innovation Fund in Brain Health (Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto) and the Medical Psychiatry Alliance, a collaborative health partnership of the University of Toronto, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, the Hospital for Sick Children, Trillium Health Partners, the MOHLTC and an anonymous donor. The opinions, results, views and conclusions reported in this paper are independent of the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.197.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.