In the mid-1990s, Dr. Heinz E. Lehmann, international pioneer in the pharmaceutical treatment of schizophrenia and depression, officer of the Order of Canada, and person in his 80s, wrote: “there is much wrong with getting old – but really not much more than with living at any age. Each age has its own, different problems and we have to learn how to best adjust to them” (Lehmann, Reference Lehmannn.d., p. 7). Despite being an active person who skied into his 80s, Dr. Lehmann’s article concretely articulates the challenges of ageism that he and others experienced and continue to experience – stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination towards older adults (Butler, Reference Butler1969; Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson2016) – a problem experienced by many older people (North & Fiske, Reference North and Fiske2015) – typically considered to be people over the age of 65. Ageism carries with it challenging psychological, social, and health and well-being ramifications (Abrams, Swift, Lamont, & Drury, Reference Abrams, Swift, Lamont and Drury2015; Helmes & Pachana, Reference Helmes and Pachana2016) and can result in inequitable treatment in health care settings (Wyman, Shiovitz-Ezra, & Bengel, Reference Wyman, Shiovitz-Ezra, Bengel, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018). A recent systematic review (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Kannoth, Levy, Wang, Lee and Levy2020) has demonstrated the serious negative health outcomes of ageism that stem from both structural (institutional) ageism and individual ageism, independent of the perpetrator’s age, sex, or ethnicity, measured across the last 50 years on all continents. Specifically, structural and individual ageism was positively associated with denial of access to health services and treatments, mental and physical illness, poor quality of life, risky health behaviours, reduced longevity, and cognitive impairment, in addition to social and vocational barriers. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated the pervasive and serious implications of ageism on older peoples’ basic human rights and value as people, perpetrated through individuals (e.g., through social media) and institutions (e.g., health care organizations) (Meisner, Reference Meisner2020). Older people have been portrayed as a homogeneous at-risk group, at times eliciting systemic finger-pointing at older people as perpetuators of the pandemic (Ayalon, Reference Ayalon2020). It is clear that addressing ageism at a societal level is critically important. In contrast to other forms of prejudice, ageism is most pervasive (McNamara & Williamson, Reference McNamara and Williamson2019) and is socially normalized (World Health Organization, 2020). Ageism can be expressed against individuals of any age group different from the perpetrator; however, the term generally encompasses age-based stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination against older people in particular (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson2016).

Rapid population aging worldwide (United Nations, 2017) has created an urgent need to understand how younger peoples’ views of the aging process and of older people can be improved, and how ageism can be reduced. Youth represent the next generation of adults who will be directly and indirectly interacting and working with older people. The language of ageism as a “global crisis” (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Sheppard, Henderson, Wassel, Cope and Barber2019, p. e7) creates an urgency to reduce ageism and increase understanding of aging among youth.

Post-secondary courses focusing on aging offer an intermediary way to teach youth about aging (typically during one semester); however, research in this area has been mixed. Both increases and decreases in fears of aging have been demonstrated (Guest, Nikzad-Terhune, Kruger, & Rowles, Reference Guest, Nikzad-Terhune, Kruger and Rowles2019; Merz, Stark, Morrow-Howell, & Carpenter, Reference Merz, Stark, Morrow-Howell and Carpenter2018). Contact theory (Allport, Reference Allport1954) suggests that exposure to outgroups may reduce prejudice; in line with this, many studies have found reduced ageism and a deeper understanding of the aging process to be associated with service-learning courses, in which students are directly connected with an older adult to complete a placement, project, or activity (Burnes et al., Reference Burnes, Sheppard, Henderson, Wassel, Cope and Barber2019; Gardner & Alegre, Reference Gardner and Alegre2019; Knapp & Stubblefield, Reference Knapp and Stubblefield2000; Neils-Strunjas et al., Reference Neils-Strunjas, Crandall, Shackelford, Dispennette, Stevens and Glascock2020; Penick, Fallshore, & Spencer, Reference Penick, Fallshore and Spencer2014; Zucchero, Reference Zucchero2011). However, service-learning with older adults may not always be feasible, in particular for courses housed in academic departments external to health care fields or those not associated with programs, placements, practicums, or projects already involving direct contact with older adults. Few studies have examined the potentially unique ability of strictly academic post-secondary courses in aging (e.g., those that lack service-learning) to provide high-quality, indirect contact with the aging process through course content. By extension, this article aims to discern the influence of taking an undergraduate psychology of aging course, specifically asking: after completing an undergraduate psychology of aging course, what are undergraduate students’ attitudes towards older adults and the aging process?

Young Adults’ Attitudes Towards Aging

People of all ages can be ageist (Gonzales, Morrow-Howell, & Gilbert, Reference Gonzales, Morrow-Howell and Gilbert2010). However, in Western societies and in those in which ageism is pervasive, young adults are consistently found to be the primary perpetrators of ageist stereotypes (North & Fiske, Reference North and Fiske2013; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Bergeron, Cowart, Ahn, Towne and Ory2017; Usta, Demir, Yönder, & Yildiz, Reference Usta, Demir, Yönder and Yildiz2012; Yilmaz, Kisa, & Zeyneloğlu, Reference Yilmaz, Kisa and Zeyneloğlu2012). In these settings, youth may view older adults as largely different from themselves, associating traits such as illness, impotency, ugliness, mental decline, mental illness, depression, senility, uselessness, isolation, poverty, and crankiness with aging (Abrams et al., Reference Abrams, Swift, Lamont and Drury2015; Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson2016). Children learn early in life to automatically categorize others based on dimensions of difference, normally within the domains of race (Steele, George, Williams, & Tay, Reference Steele, George, Williams and Tay2018), sex and gender (Perry, Pauletti, & Cooper, Reference Perry, Pauletti and Cooper2019), and age (Bergman, Reference Bergman and Nelson2017). By young adulthood, individual ageist perspectives have typically been bolstered by a youth-focused media and society (Berger, Reference Berger2017). For example, Ellison (Reference Ellison2014) found agelessness and transcendence of age to be significant themes within anti-aging skin care advertising, and Edström (Reference Edström2018) found older people, in particular older women, to be largely invisible from news, fiction, and advertising. Finally, Chivers (Reference Chivers2003, Reference Chivers, Hole, Jelača, Kaplan and Petro2017), Vasil and Wass (Reference Vasil and Wass1993), and Ylänne (Reference Ylänne, Twigg and Martin2015) have shown how popular Western media, culture, and literature often disempower and negatively portray older women in particular, describing older female bodies as repulsive, older minds as deteriorating, and older wisdom as irrelevant. Western youth appear to be exposed almost exclusively to older adults representing negatively stereotyped archetypes (Nelson, Reference Nelson and Nelson2016).

As members of families, neighbourhoods, and organizations, younger members of ageist societies typically do not regularly engage with older people in their day-to-day lives. In the West, familial values of past generations commonly included older people as valued and respected members of intergenerational households (Connidis & Barnett, Reference Connidis and Barnett2018). However, given geographic mobility and the changing nature of families, regular grandparent interaction has become less integral to the modern family unit (Novak, Campbell, & Northcott, Reference Novak, Campbell and Northcott2018). Grandchildren who engage in regular, high-quality interactions with grandparents, in particular those in good health, are often less ageist (Flamion, Missotten, Marquet, & Adam, Reference Flamion, Missotten, Marquet and Adam2019). However, youth who regularly are in contact with dependent older adults are usually more ageist (Hawkley, Norman, & Agha, Reference Hawkley, Norman and Agha2019). Further, there have been mixed results showing both positive (Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Mirza, Austen, Hsieh, Klinger and Kuah2020; Penick et al., Reference Penick, Fallshore and Spencer2014; Wideman, Reference Wideman2014) and negative (Larraz Gómez, Reference Larraz Gómez2013) implications for ageism among young adults who live with older people. Although intergenerational contact theory demonstrates that limited, regular contact between youth and older people may both enhance and reduce ageist perspectives, ageism has been consistently reinforced by normal, healthy, and identity-protecting developmental trajectories of youth. As a result, ageism cannot be reduced to or by a simple equation of contact, despite Allport’s (Reference Allport1954) foundational assertion that increased contact reduces prejudice.

Post-Secondary Pedagogical Interventions

Minimizing ageism at important developmental junctures, in particular during young adulthood, is critical. The gerontological education literature has consistently articulated the ongoing need to strengthen young peoples’ positive perceptions of older adults (Fernández, Castroa, Aguayoa, Gonzálezb, & Martíneza, Reference Fernández, Castroa, Aguayoa, Gonzálezb and Martíneza2018). This is especially key because frequent and impactful intergenerational contact opportunities may be limited in a largely age-segregated society (Drury, Hutchison, & Abrams, Reference Drury, Hutchison and Abrams2016). Exposure to a gerontology curriculum can improve post-secondary students’ understanding about older adults and the aging process (e.g., Chonody, Reference Chonody2015; Cottle & Glover, Reference Cottle and Glover2007; Ferrario, Freeman, Nellett, & Scheel, Reference Ferrario, Freeman, Nellett and Scheel2008; Lee, Shin, & Greiner, Reference Lee, Shin and Greiner2015; O’Hanlon & Brookover, Reference O’Hanlon and Brookover2002). However, service-learning interventions are reportedly most effective at reducing ageism (Chonody, Reference Chonody2015).

Service-learning experiences take place in ecologically valid settings and typically involve direct interaction with community members, aiming to meet both curriculum requirements and a community need (Jenkins & Sheehey, Reference Jenkins and Sheehey2019). More specifically, intergenerational service-learning seeks to co-create meaningful relationships and educational products between younger and older adults. Improved mental health and emotional and social growth for both cohorts has been identified as an outcome of intergenerational service-learning (Heo, King, Lee, Kim, & Ni, Reference Heo, King, Lee, Kim and Ni2014; Oakes & Sheehan, Reference Oakes and Sheehan2014; Tam, Reference Tam2014), and importantly, reductions in ageism have been consistently found (Chonody, Reference Chonody2015; Karasik, Reference Karasik2013; Oakes & Sheehan, Reference Oakes and Sheehan2014; Penick et al., Reference Penick, Fallshore and Spencer2014). However, service-learning can be logistically challenging and time consuming to implement. It can require one consistent instructor to build capacity – not always possible in an era of limited-term faculty appointments – and can have associated costs not covered by the department. Additionally, service-learning requires community connections that may be unfeasible given the time, energy, community embeddedness, and instructor consistency that these connections take to build (Mayer, Blume, Black, & Stevens, Reference Mayer, Blume, Black and Stevens2019; Schelbe, Petracchi, & Weaver, Reference Schelbe, Petracchi and Weaver2014).

Given these limitations, but also given the demonstrated value and role of academic courses in reducing ageism in undergraduate students, it is important to determine whether high-quality, attitude-changing content can be delivered in the form of a lecture-based, gerontology-focused university course that does not contain service-learning (e.g., relies on class-based lectures, tests, and assignments). To expand on these themes, we turn to a study conducted across two Canadian universities that examined the impacts of a standard undergraduate psychology of aging course on undergraduate students’ perceptions and attitudes towards older adults and the aging process.

Method

Two Canadian Universities Offering Psychology of Aging Courses

A qualitative case study analysis of two similar classes at two Canadian universities was conducted between 2019 and 2020. Cape Breton University (U1; 5,5111 students enrolled in 2019) is located in Sydney, Nova Scotia, in Atlantic Canada, approximately 410 km from Halifax, the province’s capital and major urban centre. Trent University (U2; 11,079 students enrolled in 2019) is located in Peterborough, Ontario, in Eastern Canada, approximately 150 km from Toronto, the province’s capital and largest metropolitan centre. Both institutions are primarily undergraduate focused and are considered small universities for their respective province. They are also both set within aging populations: in U1’s city (Sydney, NS) 23.2 per cent of the people are over 65 years of age (compared with the provincial rate of 19.9% over 65) (Statistics Canada, 2017a) and in U2’s city (Peterborough, ON) 22.3 per cent of its residents are over the age of 65 (compared with the provincial rate of 16.7% over 65) (Statistics Canada, 2017b).

Within the two universities, this project studied perceptions and attitudes towards older adults and the aging process among undergraduate students who had completed the course. Both courses were offered through each university’s department of psychology and were the only departmental courses of their kind (e.g., with content specifically focused on aging). Gerontology: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Aging was offered at U1 and was taught by Dr. Thériault. This course was offered at the second year level, with 23 students enrolled in the first year of the study (the 2018–19 academic year) and 29 enrolled in the second year (the 2019–20 academic year), with an average weekly attendance of 20 students in both years. Adult Development and Aging was offered at U2 and was taught by Dr. Russell. This course was offered at the third year level, with 43 students registered in the first year of the study and 57 students registered in the second year, with an average weekly attendance of 35 students in both years. Both courses examined theory and research of aging within a lifespan framework using an intersectional and social determinants of health lens. Topics included biological, psychological, and social aging processes; health and aging; the aging brain; money, work and retirement; ethnicity and aging; and end-of-life issues. The courses were taught in an in-person lecture style (with the exception of the last three lectures in the 2020 cohort, delivered online because of the COVID-19 pandemic), and supporting resources included readings from academic and grey literature, videos, seminar discussions, and student-led presentations.

Participants

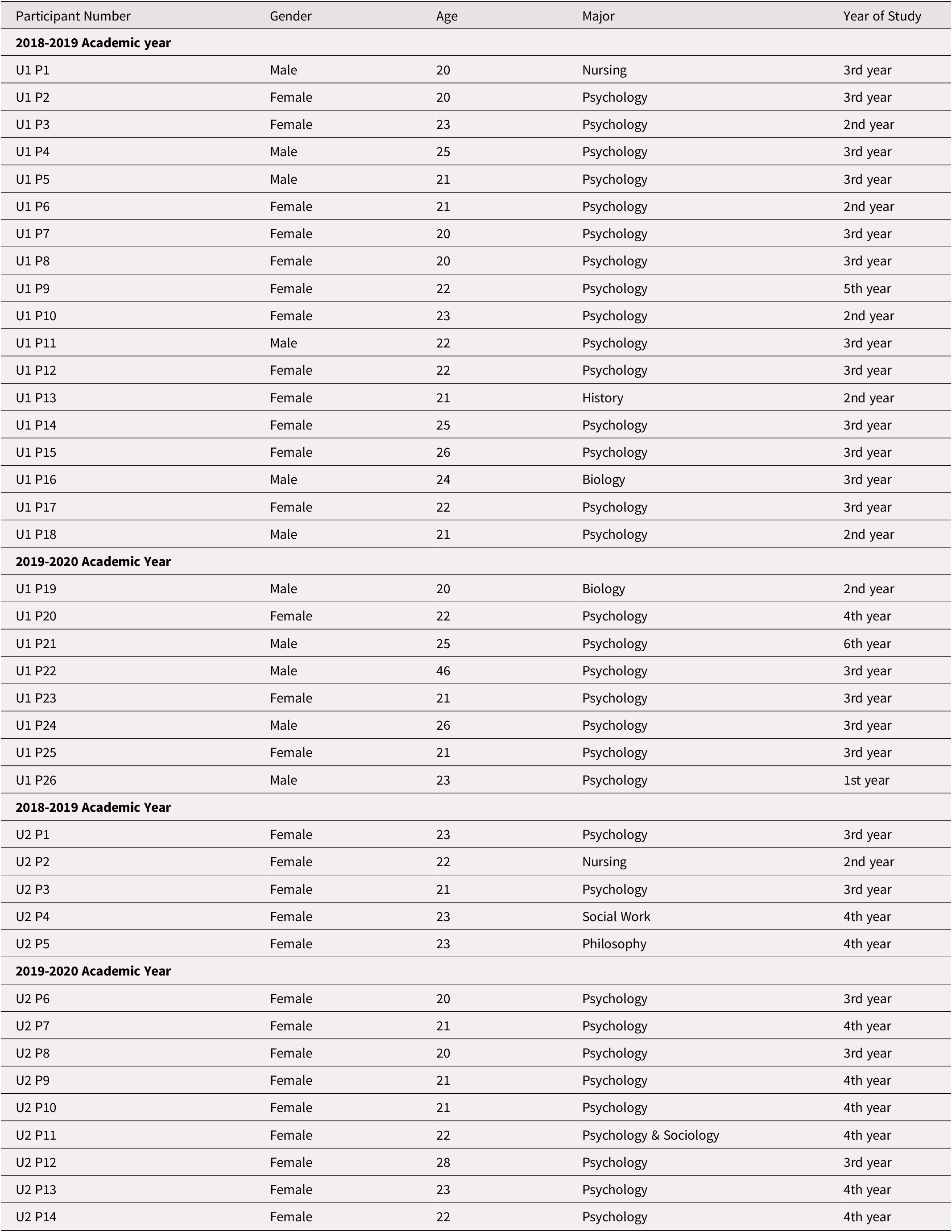

Following ethics approval from research ethics boards at both Cape Breton University (U1) and Trent University (U2), a total of 40 students were recruited (26 U1 and 14 at U2) from the four psychology of aging offerings across both universities and academic terms of this study (2018–19: n = 23 students, and 2019–20: n = 17 students) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Participant demographic information

It is important to note that during the second year of the study, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, classes at both universities moved to online formats in March, 2020, with several weeks left to the semester. Given the inability to meet in person, study recruitment was completed electronically during a time of unease for many students. Therefore, the pandemic likely explains a slightly lower number of participants in the 2019–20 academic year.

Data Collection

Focus groups

Focus groups were conducted with undergraduate students from both universities, upon the completion of the psychology of aging course in the 2018–19 academic year (April, 2019). Two in-person focus groups were held at each university, with a total of 23 participants (U1: n = 18, U2: n = 5). Recruitment and focus group facilitation was conducted by a research assistant to ensure that student identities remained unknown to the course instructors, aiming to reduce recruitment and response bias, acquiescence, and any discomfort that students might experience in making challenging or unpleasant statements to their professors. The research assistant emailed all students in the course to recruit them to the study and made a posting on the course Web site. Focus groups lasted approximately 90 minutes, were audio recorded, and consisted of facilitated, semi-structured discussion between students on how taking the course impacted their perceptions of the aging process and of older adults. Major focus group questions included: What was one thing about aging that surprised you? Did you take away anything from the course that relates to your own life (for example, your parents, grandparents, coworkers, or older community members you may know)? Has this course impacted the way you view your own aging? Has this course has impacted your perspectives on ageism? What comes to mind when you think about the impact of this course on you, as a person?

Interviews

The original study design included focus groups in both study years, but because of the COVID-19 pandemic and the move to online class delivery, the researchers decided to switch to telephone interviews with individual students to adhere to the physical distancing measures that were in place in Canada at the time of data collection. Following course completion, interviews were conducted with students from the psychology of aging courses in the 2019–20 academic year (April, 2020). A total of 17 interviews were conducted (U1: n = 8, U2: n = 9). Research assistants recruited participants via e-mail and through a posting on the course Web site. Like the focus groups, interviews were conducted by research assistants to ensure that students’ identities remained anonymous to the course instructors/researchers, and questions followed the same protocol used in the focus groups. Interviews were approximately 30 minutes in length and were audio recorded.

Iterative Collaborative Qualitative Analysis

Focus group and interview recordings were transcribed verbatim to portray the spoken words of the sessions. A qualitative thematic content analysis of transcripts followed Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) principles and phases, and, as outlined in Russell, Skinner, and Fowler (Reference Russell, Skinner and Fowler2019), an iterative collaborative qualitative analysis (ICQA) was undertaken. Both processes incorporate the systematic development, testing, and revising of a code manual and dual coder collaboration to reinforce dependability, with team adjustment throughout the analysis drawn from Hall, Long, Bermback, Jordan, and Patterson (Reference Hall, Long, Bermback, Jordan and Patterson2005). To begin, two coders separately reviewed the transcripts, highlighting prevalent findings and themes and developing a draft code manual. The manual was collaboratively tested on transcript samples and further refined until no inconsistencies or points of confusion remained.

Upon completion, all transcripts were read and reviewed to finalize the code list, which was then tested on select transcripts to determine if revisions were needed before establishing a confirmed code manual. The five preliminary emergent codes included: empathy, planning for the future, broadening academic understanding of gerontology, debunking aging stereotypes, and developing personal connection. These five initial codes were further condensed to include three final codes, including: reduced ageism, developing personal connections, and deeper understanding of the aging process. The detailed code list can be shared upon request to Dr. Russell.

The first coding occurred when one author assigned code name(s) to sections of raw data (double coding was considered acceptable, triple coding was avoided). Second coding followed, in which a second researcher reviewed first-coded transcripts, cross-checking and editing the first coding against the manual. Any inconsistencies were discussed and resolved between coders. Three code documents were created (one per code) that included all text from that code agglomerated across all participants. Based on these code documents, three comprehensive code analysis documents were written, each providing a detailed overview of concepts entrenched within that particular code (e.g., several pages of text were written, thoroughly summarizing each code). Holistically analyzed by the authors for a primary emergent theme, these three documents formed the evidence from which the study’s key findings developed. Multi-collaborator coding built into each stage strengthened reliability (Schoenberg, Miller, & Pruchno, Reference Schoenberg, Miller and Pruchno2011), with only cross-cutting themes from the final stage of the analysis being included in the following findings section. Participants are anonymously cited to ensure their confidentiality and are quoted verbatim to enhance the authenticity of authors’ interpretation of the data.

Findings

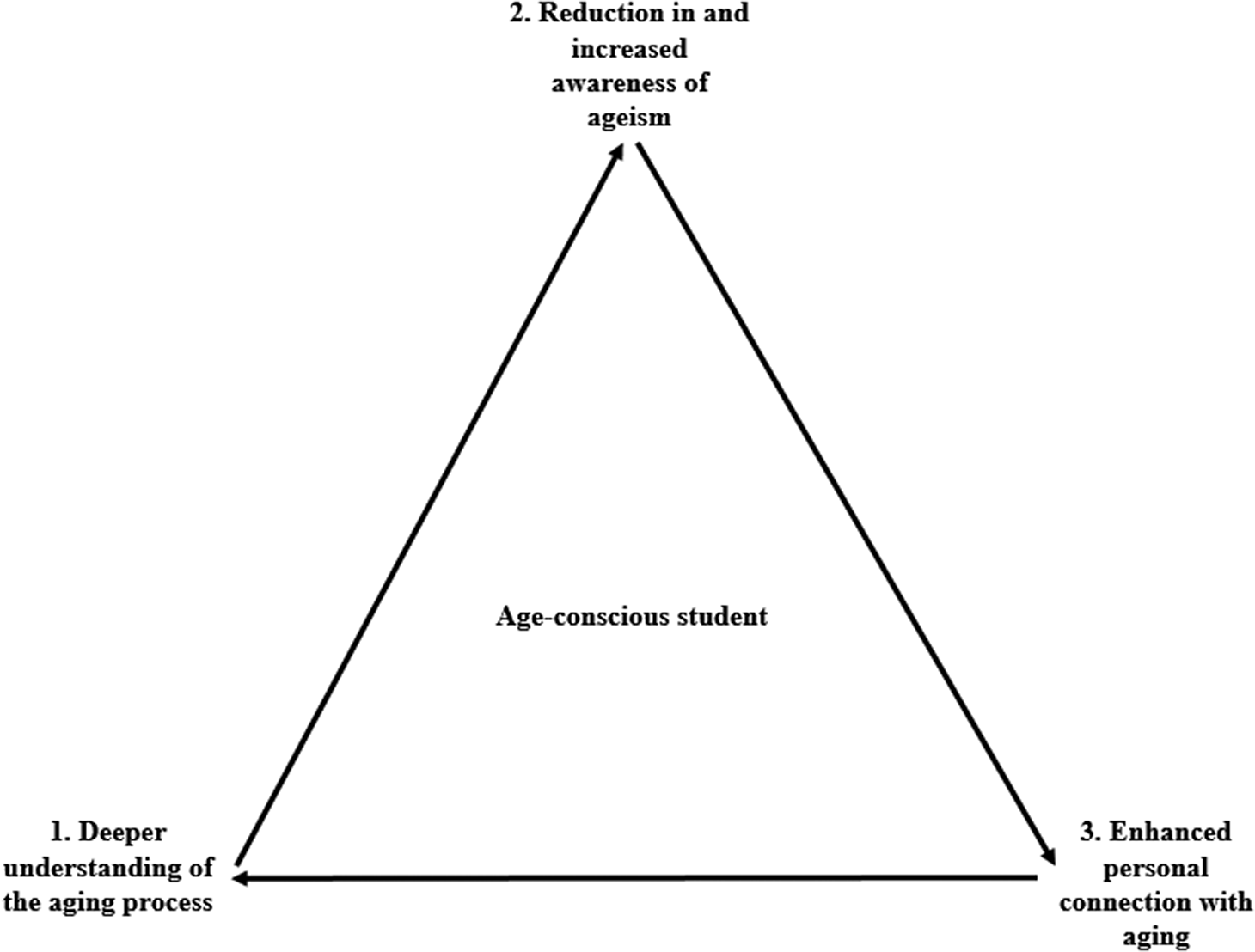

As presented in Figure 1, a concept emerged that suggests that classroom-based course content stimulated a deeper understanding of the aging process, prompting a reduction in and increased awareness of ageism and an enhanced personal connection with aging, ultimately facilitating the development of an age-conscious student.

Figure 1. Facilitating age-conscious student development through lecture-based courses on aging

Deeper Understanding of the Aging Process

After taking the courses and working through the course content, students reported feeling a deeper understanding of the aging process. Course material presented a diverse representation of the aging experience, helping to debunk students’ initial stereotypes of aging and creating a lens of intersectionality through which aging was viewed as impacted by gender, race, sexuality, class, and ability: “Learning about the difficulties that different marginalized groups face when they are older…it was something that I never thought about. It was not something that I really much thought into because it’s not a visible issue” (U1 P20). These diverse perspectives allowed students to more deeply understand the challenges that some aging populations face, which was something that they may not have previously considered.

Students also reflected on learning about the diversity of how people age. Many students shared how their preconceived notions surrounding aging held a “doom and gloom” narrative. However, course content debunked this stereotype: “A lot of the stuff that we learned about successful aging is something that you don’t think about. A lot of times before I took this course the idea of aging is very scary and you think about how debilitating it can be. But, then you see how your definition for what aging successfully becomes as you age…it starts to change” (U1 P18). One student described their own grandmother as active but explained that the course revealed a different side of aging previously unknown to them: “My grandma, she likes skiing and snowboarding and jumping in the water and stuff like that. In class, what is also talked about is maybe the not so great sides of aging. It really makes you realize that some people really do struggle, and it’s interesting to look at it from that perspective” (U2 P7).

Although age-related decline was an important course component, students were surprised to learn that older adults are often creative, complex, happy, independent, and often still growing, learning, and satisfied with life. Terms such as “eye opening”, “shocking”, “surprising”, and “outlook-changing” referred to insights into the positive side of growing older. Students felt that the view that aging is strictly a negative part of the life cycle facilitated their own and/or others’ ageism: “Growing up in Cape Breton, this is what happens when you get old: you collect a pension. You get old and die. What I learned was that that’s not true. That stood out for me. That was an eye opener. You don’t just have to work your job and collect your pension and that is it for your life” (U1 P22). The courses’ balanced, multidimensional depiction of aging contradicted assumptions of decline: “I just kind of always thought of aging as a negative part of the life cycle. So I think the fact that it was also positive was surprising” (U2 P8). Many viewed this generationally: “I feel like our society or maybe our generation specifically has this idea that aging is just like a bad, horrible time or that your body stops functioning and all of those things. So I feel like that perception shifted for me throughout the course because of what we learned. It shifted the way I view aging and the older adult in general” (U2 P11).

Students described their attitudes towards the aging process as shifting for the better. Learning about the varying biological, psychological, and social aspects of aging, students became more empathetic towards older adults: “I keep going back to this whole like, deaf and losing your eyesight as you age…that just surprised me so much and it was so impactful. You always think, ‘Oh, the grumpy old man’…But no. He can’t hear so he can’t talk to you, he can’t listen to his favourite music. I’d be grumpy too” (U2 P1).

Empathy prompted a desire to help improve older peoples’ lives; with many suggesting that they were starting to consider careers working with older adults: “This class helped a lot. It helped me realize that I really want to learn more about this, not just because [dementia] is an illness or a neurological decline that I want to explore. I want, overall, to make life better for people. So, if I can learn the mechanisms of treatment, I can make cognitive reality better. If I can slow down the process or just make the last few years of their lives better, I want to do it. I just want them to have a better life” (U1 P20). Further, deeply engaging with balanced facets of the aging process led to a recognition and reduction of ageist stereotypes.

Reduction in and Increased Awareness of Ageism

Facilitated by a deepened understanding of the aging process, both reduced ageism and being able to observe and defend against ageism were consistently reported. Students listed specific examples of ageist assumptions that they had encountered or personally held, including perspectives of older people as forgetful, slow drivers, non-sexual, grumpy, physically and/or financially dependent, cute, conservative, boring, and uninterested in community participation. The pervasiveness and destructiveness of ageist attitudes were compared to racism and sexism but described as hidden from conversation: “We talk about racism and sexism in daily life and that [discussion] seems to be very prevalent. But ageism is something that isn’t. So that was something that was really interesting to both consider and to be able to be aware of myself” (U2 P8). Western society was depicted as unsupportive of aging, enhancing challenges faced by marginalized older people, and providing mechanisms by which ageism was perpetuated. However, for students, the course identified and contextualized these external factors (e.g., applied a social determinants of health model to aging).

Course content inspired attitude and behaviour change amongst students who readily described themselves as having been complicit in perpetuating ageism, and/or silent in the face of ageist comments. Many students admitted that they had unwittingly held and often perpetuated ageist views through ageist jokes, terminology, elderspeak, impatience, and condescension or judgment towards older people: “At first, I was kind of appalled with myself because I hold a lot of these attitudes” (U2 P8). Whether it was how they spoke to older people or attitudes that they had internalized, specific examples supported students’ own past ageist attitudes or behaviours: “Everything we learned sits in my mind and it’s like a seed planted and it’s already changed me so much in the way that I interact with people. My parents were buying a house and they didn’t have the steps in the front door. The agent gave my mom a hand up and then my dad. He was going to give me a hand up, but I said, ‘That’s okay, I am still young,’ but then I thought to myself, ‘Why did I say that’ and then recognized it. It completely took a shift and made me way less ignorant and I don’t think like that anymore. Moving forward it will make me aware of what I am saying and the ways I might be perpetuating ageism” (U1 P21). Another student reflected upon their unintentionally benevolently ageist practices, newly salient following delivery of course content: “I’m really bad for that at work. And now I’ve got to watch it. They call it elderspeak, but it is almost like baby talking. Some little cute – well that’s another thing, is that I call them all cute – but some cute little old lady comes up to your register and you’re ringing her through, and I can’t help but call her darlin’ and she’s just so cute and little” (U1 P17). Another had become more patient following the course: “I even noticed the other day that now I am able to wait behind them in line. I am more understanding now. In general, I think I have a more positive attitude [toward older people] after taking this course” (U1 P23).

Equipped with an ability to articulate arguments based on data-driven course material, students reported feeling prepared and compelled to dispel ageist attitudes or behaviours where in the past they may have been silent: “It’s definitely helped to know more specifics. I kind of had some of the negative stereotypes that potentially people who haven’t been around older adults may have had. The specifics and the studies behind it really helps. Knowledge is power and being able to talk more openly about things and know that I’m more knowledgeable allows me to say, ‘I know it’s not that way, because of this [course]’” (U1 P9).

A polarization of aging was explicitly described by nearly all students. Older people were placed either “in the ‘boomer remover’ camp or the ‘I really like my grandpa’ camp” (U1 P19), but in retrospect, students felt that these mean-hearted or benevolent perspectives were equally ageist. Preconceived notions of aging were described from a white, heteronormative, and wealthy perspective (e.g., a stereotypical carefree retirement in which health and accomplishment later in life is the norm), or conversely, one characterized by decline, depression, dependence, and poverty: “It challenged a lot of the stereotypes that I had of either you’re having a super happy and chill retirement versus like you’re sad and miserable. I was going off the media portrayal of old age – being super happy and enjoying life carefree or you’re being fat in your home. So it [the course] has changed my view around that which I now understand was a horrible view to have” (U2 P10).

The courses contextualized aging and presented it as a spectrum inclusive of many unique pathways to aging, creating an effective tool in tempering ageist views: “They’re just like us but older. That view is masked in all these stereotypes and stuff. So, it really does go to show that like, older people, yeah, they are us, but like the same. Some people are idiots, some people are rude, some people are really nice, some people are really cute, and that’s just like, old people are the same way. You don’t have to judge them all just by one stereotype” (U1 P17). Ageism can be dispelled by balanced, diverse views of aging based in current science: “I think it did a really good job in bringing awareness to so many different dimensions of an older person – combat all of the stereotypes that I think a lot of people do hold” (U2 P3). Feeling more educated on the aging process and ageism, students described having developed a new personal connection with aging.

Enhanced Personal Connection with Aging

A deeper understanding of the aging process and a reduction of ageist attitudes enhanced students’ connections with older adults (in the community at large and within their personal life), and with their own aging. This practical and personal application of course material was positively received: “I’m really, really pleased with the real-life applications. It’s not just words on a page. It’s something that I can apply to real life and this stays with you forever” (U2 P12). Whether through employment or volunteering, students described experiencing enhanced interactions and connections with older people: “I noticed something that I have started doing more with older adults, is I find the opportunity to talk and engaged them a bit more” (U1 P20). Deeper consideration of aging also helped some interact with older people at work: “I work with an older gentleman as a caretaker. [The course] helped me out with him a little bit because he is cognitively impaired and he’s blind and partially paralyzed…so it’s definitely helped me to see the unseen challenges that he’s gone through over the years” (U2 P6).

Students identified with and related course topics to personal experiences with aging family members: “My parents are baby boomers. My dad is 66 and my mom is 64. The class was helpful in knowing how to support them in their aging” (U1 P21). This included becoming more empathetic towards older relatives’ aging processes: “[The course] has made me realize that my grandparents are not just passive creatures going through life having life happen to them…they can still contribute and they can still do things” (U2 P1).

Many students’ fears of growing older decreased: “We are always aging. It’s a process and I am less scared now than I was because I have read and learned about it and all the amazing things [older adults] do when they are older, and all the time they have to enjoy life” (U1 P21). Learning about the diversity of the aging experience, for this student, reduced their worry about aging as a member of a minority group: “It’s kind of scary to think of. I am already a minority and it was worrisome to learn about how aging is going to be different for me. I am kind of fearful of that but at the same time, I feel more motivated now because I know that this can be something good. I know this can be exciting and a new part of my life that I can embrace. It’s not always going to be easy and my health is not going to be the same, but I know that what I do now matters” (U1 P21). For many, the class communicated the extent to which lifestyle may affect aging: “Before this class, I was really scared of aging because obviously it’s not painted in a very good light. This course taught me more of the control I can take into my own hands as to how I age. Not that I am going to age perfectly but I can take a lot more preventative measures to keep myself healthy by being more mobile, eating better, taking antioxidants, wearing sunscreen. It gives you more power when you have the information and you make decisions based on that instead of just being scared about it” (U2 P6).

Immersion in course content was important in connecting students more realistically and deeply with the diverse and nuanced nature of their own aging. Being less fearful of growing older, many described a heightened awareness of the process, a greater sense of ease with their own aging, and excitement with having the proper knowledge to navigate later life: “I’m excited. Not to be old, but I’m kind of excited to grow up and see where I go. Now that I sort of know of a way that I can age successfully, I’m excited to see how I can put this learning to the test” (U1 P6). By engaging with their own aging and feeling connected to older people, the courses allowed students to create a balanced and positive narrative around their own and others’ aging.

Discussion

Based on an analysis of undergraduate students’ attitudes towards older adults and the aging process, the age-conscious student concept emerged. Specifically, an age-conscious student is aware of the full spectrum of the aging process, is not themselves ageist, is attuned to ageism among others, does not, on the whole, fear their own aging, and finally, relates well to older adults. Further, an age-conscious student understands diversity among older adults, recognizing that, as with all age cohorts, stereotypes associated with a particular generation overlook the range of individual traits, including factors such as personality, health status, well-being, and life satisfaction. This suggests that environments typical of post-secondary lecture-based courses – those that exclude service-learning or engagement with older adults – may facilitate the development of an age-conscious student.

Pushing Back against Unawareness of Aging: Youth and Aging

Understanding the feelings that young adults may hold towards aging is contextually important in understanding positive attitudinal changes towards aging, and the growth of an age-conscious student. Western society typically includes only limited intergenerational contact, and beyond this, it is developmentally normal for young adults to feel fearful or negative towards growing older. Martens, Goldenberg, and Greenberg (Reference Martens, Goldenberg and Greenberg2005)’s terror management theory suggests that ageism exists and is perpetuated because older adults represent the future in which, for everyone, death is certain, physical deterioration is probable, and the loss of characteristics that enhance one’s self-worth is possible. In particular, older adults with physical and cognitive limitations may trigger thoughts of mortality among young adults (O’Connor & McFadden, Reference O’Connor and McFadden2012). Further, social identity theory has similarly explained the tendency to elevate and value one’s own age group while similarly viewing other generations as lesser, ultimately reinforcing a positive self-identity (Lev, Wurm, & Ayalon, Reference Lev, Wurm, Ayalon, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018). With a sense of fear inherent in growing older and moving away from youth, dread of appearing old and of aging can become aggravated (Chonody & Teater, Reference Chonody and Teater2016). This theory explains how an ingroup (in this case, youth) may hold negative stereotypes and/or attitudes towards an outgroup (older people), but that these negative feelings are developmentally logical.

Although intergenerational contact theory demonstrates that limited, regular contact between young and older people may enhance or reduce ageist perspectives (Flamion et al., Reference Flamion, Missotten, Marquet and Adam2019; Hawkley et al., Reference Hawkley, Norman and Agha2019), ageism, misunderstanding of aging, and fears of aging have been reinforced by these normal, healthy, and identity-protecting developmental trajectories of youth (Lev et al., Reference Lev, Wurm, Ayalon, Ayalon and Tesch-Römer2018; Martens et al., Reference Martens, Goldenberg and Greenberg2005). Nonetheless, there are many examples from non-Western cultures in which older adults are held in high esteem by youth (Sung, Reference Sung2004), and therefore, it is important that the present research be interpreted within its Western context only. Although perhaps developmentally appropriate, the pervasiveness of ageism and fear and confusion about the aging process among youth may not be socially appropriate. Therefore, an understanding of relatively simplistic ways to combat these attitudes at a pedagogical level is essential.

Pedagogical Implications of Findings

These findings demonstrate that fostering an age-conscious perspective among undergraduate students may require a relatively brief (e.g., one semester) duration of training, and that traditional academic means are sufficient to prompt this change. In contrast to prior research, it appears that although beneficial (Chonody, Reference Chonody2015), applied innovation in the form of service-learning integrated throughout the course is not necessary to prompt a heightened awareness of aging. This finding is particularly relevant, as previous research (Chonody, Reference Chonody2015; Cottle & Glover, Reference Cottle and Glover2007; Ferrario et al., Reference Ferrario, Freeman, Nellett and Scheel2008; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shin and Greiner2015; O’Hanlon & Brookover, Reference O’Hanlon and Brookover2002) has demonstrated positive pedagogical outcomes related to gerontology curricula. However, this has primarily been shown among courses with regular, in-person interaction between students and older people that is consistently integrated throughout the course (Bousfield & Hutchison, Reference Bousfield and Hutchison2010; Drury et al., Reference Drury, Hutchison and Abrams2016). Logistical and budgetary limitations to service-learning courses in typical academic settings, especially those external to professional health and social care programs, may prevent academic programs or departments from implementing standard-format courses on aging, especially if social benefits (e.g., decreased ageism) are dependent on an applied learning approach. However, there is a growing interest among post-secondary institutions in developing aging foci, given increasing awareness of the aging population and interest in developing innovative, socially relevant courses. This momentum at the institutional level has created a need to understand whether standard-format gerontology courses housed within a variety of relevant disciplines may affect change similar to that attributed within the service-learning literature (Chonody, Reference Chonody2015; Oakes & Sheehan, Reference Oakes and Sheehan2014; Penick et al., Reference Penick, Fallshore and Spencer2014). Further, the limitations of typical post-secondary classroom environments rarely allow for service-learning to be incorporated alongside the delivery of standard course content, testing, and assessment.

Post-secondary gerontology classes outside health and gerontological programs are relatively uncommon (Hoge, Karel, Zeiss, Alegria, & Moye, Reference Hoge, Karel, Zeiss, Alegria and Moye2015). More common lifespan-focused courses, however, typically only cover topics up to young or middle adulthood, with older age encompassing only a small course component. The present findings imply that encouraging the development of gerontological curricula in a variety of relevant academic fields (e.g., anthropology, biology, English literature, geography, psychology, sociology), based on evidence of positive attitudinal change among undergraduate students, is likely a worthwhile effort.

Social Implications of Findings

These research findings extend beyond pedagogy and have social and vocational implications. Career decisions are often made during post-secondary education, and, therefore, educating young adults at this stage about the realities of aging is critical, as students in fields beyond health and social care may be unaware of the economic, social, and personal value of working with older people (Gross & Eshbaugh, Reference Gross and Eshbaugh2011). This may not only reduce ageism, but it is possible that course outcomes might encourage age-conscious students to consider careers involving working with older adults, directly or indirectly. Further, reaching students taking the course for reasons aside from personal interest in aging (e.g., scheduling, degree requirements) is relevant, as they may be unlikely to enroll in a dedicated aging-focused, service-learning course and therefore would not receive the social benefits identified in this research. For those enrolled in professional health and social care educational streams, these results are still important, as ageism is still prevalent among this population (Gewirtz-Meydan, Even-Zohar, & Werner, Reference Gewirtz-Meydan, Even-Zohar and Werner2018). By finding ways to develop age-conscious students amongst programs unlikely to recruit students with a previous interest in aging, standard academic courses may assist in filling the urgent gap in a variety of fields that support older adults.

Understanding methods that may be effective in reduce ageism and fears of aging, and increasing balanced understanding of the aging process among a new cohort of young adults, is also socially relevant. Youth who will never professionally interact with older adults will nonetheless likely interact with older adults in public or private circumstances throughout their lives. Rather than feeling ageist or fearful, age-conscious youth may be more likely to interact appropriately with older people whom they encounter, and to fear their own aging less (Merz et al., Reference Merz, Stark, Morrow-Howell and Carpenter2018). Helping to develop more socially conscious citizens is at the core of these findings. Understanding ways to encourage age-consciousness at the post-secondary level, independent of the logistically challenging addendum of service-learning, provides a way to conceptualize a relatively simple social role for post-secondary institutions.

Limitations

Despite the significant impact of these courses on students demonstrated in the present research, the study design brought with it some limitations. First, course goals and learning materials included addressing and debunking socially held ageist beliefs and practices. Although research assistants explicitly distanced themselves from course objectives and learning outcomes, it is possible that study participants nonetheless felt the need to “perform” an identity of a good student who has met the learning objectives. It is also possible that heightened awareness of issues facing older people during the COVID-19 pandemic further reduced ageism, or conversely, that ageism brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic minimized the positive effects of course content on ageism. Second, the final three lectures of the 2020 cohort at both institutions were delivered online and the data collected through individual interviews (instead of focus groups) because of the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, slight differences associated with the course conclusion and final data collection across 2019 and 2020 cohorts may have impacted these findings. Third, findings may be biased by the self-selective nature of participation; however, it is possible that by using relevant incentives for both the 2019 and 2020 cohorts (a catered lunch in 2019 and a draw for a VISA gift card in 2020), the biasing effects of self-selection may have been minimized. Fourth, these data were drawn from two psychology courses at two similar Canadian universities across two cohorts of undergraduate students.

Despite these limitations, it is unlikely that this concept is unique to a Canadian setting, or is specific to these institutions or instructors. By drawing from courses structured around typical course calendar descriptions within undergraduate psychology programs, not developed by or specific to the individual instructor, there is nothing unique about the content covered in these courses.

Indeed, these courses could likely be housed in other related departments or adapted to other disciplines entirely. Further, standard North American textbooks appropriate for any Western psychology program were used; therefore, it is likely that adopting a gerontological textbook that is culturally relevant to the institution would achieve a similar outcome. Underscoring this limitation, however, is the concept that youth ageism may be less pervasive in some non-Western cultures, in which older adults may be more esteemed by youth; therefore, the present results should be interpreted within the context of a primarily ageist society. To determine the pervasiveness of the age-conscious student concept, research may adapt the present methodological approach to departments outside of psychology (e.g., anthropology, biology, English literature, geography, sociology), to other academic institutions types (e.g., larger or smaller universities, colleges), or to different geographic settings (e.g., institutions housed in urban centres; countries outside of Canada; settings with higher or lower relative population aging).

Conclusion

As was pithily stated by Hagestad and Uhlenberg (Reference Hagestad and Uhlenberg2005), “efforts aimed at cross‐age interactions create ephemeral and quite superficial interactions. [ … ] to have school children sing carols in the old people’s home at Christmas time or inviting an old person for one session [ … ] to talk about World War II will not do the job of forging personal knowledge and viable ties” (p. 357). Although this speaks only to superficial service-learning, it encapsulates the value of the present findings, in which students’ perceptions about aging were positively affected. Specifically, course content stimulated a deeper understanding of the aging process, prompting a reduction in and increased awareness of ageism, and enhancing personal connection with aging, ultimately facilitating the development of a cohort of age-conscious undergraduate students. For institutions to maximize socially relevant outputs from lecture-based post-secondary courses on aging, resources need not be spent on developing a service-learning component. That said, inclusion of low-cost activities such as watching a documentary, inviting an older guest to the class, interviewing an older adult, or engaging in role play may expand the applied nature of lecture-based courses. The present results demonstrate that lecture-based courses focused on aging, in this case in psychology, sufficiently facilitated positive attitude change towards older adults and the aging process.