How do non-state armed groups form in intra-state armed conflicts?Footnote 1 Research on civil war has started to open the ‘black box’ of armed groups in what is called the ‘organizational turn’ in the literature.Footnote 2 Scholars have looked at the characteristics of armed groups and demonstrated their importance for the use of different types of violence and restraint,Footnote 3 with a focus on sexual violence;Footnote 4 governance of civilian populations;Footnote 5 cohesion, resilience, and survival in the face of counter-insurgency;Footnote 6 competition and alliance formation within and between armed groups;Footnote 7 and rebel-to-party transformations in the aftermath of armed conflict.Footnote 8 Combined, this work has revealed that the internal dynamics of armed groups are central to a range of outcomes of interest in the study of civil war.Footnote 9 Building on this consensus on the need for organisational-level analysis, the first systematic efforts to disaggregate armed groups have pointed out that armed groups have varied organisational foundations, which impact these outcomes.Footnote 10

However, we still know little about how armed groups emerge in different ways. Recent studies have distinguished armed groups that form in the context of broad-based mobilisation from small, poorly resourced insurgencies.Footnote 11 Scholars have also differentiated between these rebellions ‘from below’ and those ‘from above’, which form within the regime.Footnote 12 Armed groups that emerge from social movements,Footnote 13 small groups of individuals,Footnote 14 and splinters within the regimeFootnote 15 have, as a result, been studied separately. We argue that these different origins of armed groups should be considered in parallel since they are shaped by fundamentally different dynamics of conflict, and these dynamics are central to understanding how armed groups emerge in different ways. Efforts to disaggregate pre-existing organisations that lie at the foundation of armed groups represent an important step in the analysis of different armed group origins.Footnote 16 Yet these efforts do not capture complex armed group histories, including the contexts in which armed groups form and prior experiences of their leaders and members. The very disaggregation, furthermore, shifts attention from broader patterns or constellations of organisations that could enable comparison of conflict dynamics behind different types of origins to predecessors of individual armed groups across conflicts.

Drawing on studies of social movements, civil wars, and civil–military relations that have directly engaged with the question of armed group formation, this article outlines conflict dynamics that shape armed groups in different ways to arrive at a descriptive typology of armed group origins. Our typology illuminates different conflict dynamics underlying armed group origins in the context of broad-based mobilisation, peripheral challenges to the state, and intra-regime fragmentation. We support our categorisation by mapping the resulting ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, and ‘state splinter’ types onto a range of pre-existing organisations identified through earlier cross-national data collection and by providing illustrative examples. We find that our types broadly reflect variation in armed group origins across cases. However, armed groups with different origins can coexist in the same civil war and transform over time. Moreover, actual armed groups reflect greater complexity than these broad types capture and can incorporate characteristics of different types or not readily fit in any given type. While we cannot account for the specificities of all armed groups, we introduce the category of ‘overlapping’ origins to signal this complexity. Still, we can discern whether a group has primarily ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, or ‘state splinter’ origins, and this helps us broadly characterise these groups.Footnote 17

Armed groups with ‘movement’ origins are defined by their association with broad-based mobilisation and the legitimacy that this affords, at least early on. These groups draw their members from social movement organisations and opposition networks who as a result share a collective identity.Footnote 18 They enjoy pre-existing organisational resources and at least some domestic and foreign support for the goals of the movement from which they emerge as they engage in public confrontation with the state. But their capacity to pose unified opposition to the state stems from the movement’s ability to direct their activities towards common goals.Footnote 19 These groups often fragment the broader movement as they compete with one another for human and material resources, generating complex arrangements of actors in civil wars.Footnote 20

In turn, the secrecy of armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins vis-à-vis the state defines their operations.Footnote 21 Their activities are organised outside of government purview by a limited number of members whose recruitment is based on trust and who develop organisational structures to induce discipline, particularly with regard to the spread of information.Footnote 22 These groups initially engage in minor violence against accessible state targets. Their reliance on local communities limits their violence against civilians, especially because they initially lack alliances with other non-state armed groups or foreign support. Yet access to resources over time and the need to adapt to evolving counter-insurgency can transform these organisations into full-fledged and brutal insurgent armies and even broader movements.

Finally, fragmentation within the regime defines ‘state splinter’ armed groups. These groups emerge from current or former civilian government or military whose membership is at first fixed by this background.Footnote 23 They engage in such activities as coup d’état attempts that evolve into civil wars, which might be secretly planned but are publicly executed. These activities identify and implicate individuals involved in ways that pose high stakes for and, thus, bond participants.Footnote 24 The organisations that emerge in these cases have pre-existing leadership, military resources, and skills, which form the basis of initially disciplined, cohesive groups with insider knowledge of the government’s weakness.Footnote 25 They transform as they expand to new members who lack prior government and especially military experience and as divisions within their diversifying leadership disintegrate the original core and aims of the group.

At their outset, then, ‘state splinter’ groups whose members are mobilised from the current or former military or government differ from ‘insurgent’ and ‘movement’ groups that mobilise outside of the regime, where the former groups are defined by relatively closed membership due to their inherent vulnerability vis-à-vis the state whereas groups that emerge from broad-based mobilisation have a more open membership boundary.Footnote 26 These groups also diverge in pre-existing leadership experience and skills. In general, ‘state splinter’ and ‘movement’ groups enjoy these pre-existing organisational resources that stem from their prior activities in and outside of the regime, respectively, which ‘insurgent’ groups often lack. But ‘state splinters’ have an insider understanding of the regime from which they originate, which is generally not available to ‘movement’ and ‘insurgent’ groups.

This typology offers a useful heuristic for future studies of armed group formation and outcomes of interest, including the use of violence, in cases of armed groups with different origins. It advances efforts to understand different ways in which armed groups emerge by moving beyond studies of single types of origins or highly disaggregated organisational analyses. To chart different dynamics of conflict through which armed groups emerge and the kinds of organisations that stem from these dynamics, we bring into conversation studies of social movements, civil wars, and civil–military relations, which are rarely discussed alongside each other. Our focus on conflict dynamics that shape armed groups in different ways rather than simply on organisational dimensions, such as membership and leadership, also brings organisational approaches to armed groups into a closer alignment with the ‘processual turn’ in the study of civil war, which centres on how dynamics of conflict evolve through interactions between the different actors involved.Footnote 27 Through this lens, we see that armed group formation in contexts of broad-based mobilisation, peripheral state challenges, and intra-regime fragmentation entails substantively different interactions through which the actors involved form and transform. These different dynamics of conflict at the outset of armed group activities condition their membership and leadership, at least to an extent, with implications for their ability to engage with other actors in the military, political, and social realms. Since a detailed analysis of the organisational histories of armed groups within and across the ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, and ‘state splinter’ types is beyond the scope of this article, future research should nuance these types of origins and look at how and to what extent they impact armed groups’ internal and external relations.

This article introduces our typology as a way to capture armed group origins across contexts characterised by different conflict dynamics. We begin by clarifying our analytical focus, connecting micro- and macro-level conflict dynamics through attention to the meso level of armed groups as organisations. We then situate our research in relation to relevant bodies of literature that have addressed armed group origins in different contexts. Building on this literature, we outline our typology with basic characteristics of organisations falling within each type. We demonstrate the typology’s empirical purchase by applying it to existing cross-national data and through a series of illustrative examples. We conclude with suggestions for future research.

The meso level of armed organisations

Our analysis focuses on the meso level that takes place above the level of individuals and below the level of collectivities, such as ethnic groups and sovereign states, and includes groups that interact in proximity ‘to develop the personal relations, shared symbols, and common interests that sometimes characterize these groups’.Footnote 28 In civil wars, this level has been viewed as ‘the institutional context within which interactions between political actors and civilians take place’.Footnote 29 We broaden this view to include ‘nonstate, state, civilian, and external actors’ involved across various contexts in the process of armed group formation.Footnote 30 An armed group here is ‘a group of individuals claiming to be a collective organization that uses a name to designate itself, is made up of formal structures of command and control, and intends to seize political power using violence’.Footnote 31 A basic concern of these organisations is their survival, and they form and transform their organisational structures to fulfil their basic and broader political goals.Footnote 32 Hence, we are not looking at armed groups, such as ‘extralegal groups’, that do not seek to build organisational structures towards the common goals of state challenge, even if these goals are loosely conceived and change over time.Footnote 33 For example, in Liberia, we would consider the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), which challenged the Liberian government at the beginning of the civil war, even if its goals shifted in the course of the war, but not the armed groups extracting natural resources primarily for profit.

Focusing on the meso level and on armed groups as organisations is an analytical decision that helps us connect the micro- and macro-level dynamics of conflict.Footnote 34 The organisational structures that armed groups establish have bearings on both individuals faced with these groups and the broader evolution of conflict. The ways in which armed groups recruit and socialise fighters, internally cohere and fragment, compete and form alliances with other armed actors, engage in violence against and govern civilians under their control, adapt to state repression and counter-insurgency, and co-opt international efforts are among the dynamics that make armed groups central to the analysis of conflict.Footnote 35 Yet this does not mean ‘neglecting other determinants of civil war violence’, from armed groups’ interactions with their non-state and state rivals to their social embeddedness and wider cultural setting.Footnote 36 In fact, these groups operate in systems of relationships with other non-state, state, civilian, and foreign actors that evolve as these actors interact with each other to shape dynamics of conflict.Footnote 37 Centring armed groups is a vantage point from which to approach these broader relationships that develop in civil wars. The choice to focus on armed organisations is also methodologically feasible as these groups are, by definition, relatively easily identifiable.Footnote 38

Conflict dynamics and armed group formation

What do we mean by ‘origins’ when discussing histories of armed groups? Despite the concept’s centrality to our understanding of armed group formation, existing literature on civil war has not defined it consistently. In an important conceptual move, scholars have differentiated the origins of armed groups from those of the civil wars in which they participate.Footnote 39 At the structural level, civil wars have roots in a range of economic, social, and political factors.Footnote 40 Armed groups may instrumentally use grievances and opportunities associated with these factors.Footnote 41 Yet this does not explain how these groups come to be or, more generally, how these factors translate into conflict dynamics leading to civil war. In an early organisational study of violence in civil wars, Jeremy Weinstein links armed group origins to ‘the factors that shape a rebel group’s membership’, above all, material resources highlighted in the structural scholarship on civil war.Footnote 42 He finds that the initial endowments that rebel leaders have, whether economic or social, shape the organisations they build and the violence they engage in by attracting low- and high-commitment recruits, respectively, and by enabling diverse forms of control over combatants and governance of civilian populations. However, organisationally dissimilar armed groups have been funded by comparable resources.Footnote 43 Furthermore, the approach focused on endowments considers the question of organisation once armed groups have formed and violence is underway, whereas the origins of armed groups precede such ‘viability’, that is, a point at which ‘a rebel group can pose at least a minimal threat to the authority of the incumbent government’.Footnote 44

At their core, studies that conflate the origins of armed groups with those of civil wars or associate armed group origins with such factors as material resources are likely to miss ‘how insurgent groups are constructed’ and what conflict dynamics shape their formation.Footnote 45 Our notion of armed group origins encompasses the broader context in which armed groups emerge and the ways in which individuals involved in them build their organisations. We turn to recent studies of social movements, civil wars, and civil–military relations that have addressed this question to understand the different dynamics of conflict underlying armed group formation and develop a typology of armed group origins drawing on this literature.

Broad-based mobilisation

Civil war has been traditionally seen as developing from broad-based mobilisation, which is characteristic of social movements.Footnote 46 Three interrelated strands in the literature on social movements - radicalisation of social movements, escalation of non-violent campaigns, and clandestine political violence - help situate our study of armed group origins in civil war.Footnote 47 Insights from this research, combined, provide an account of armed group formation in the context of broad-based mobilisation.

Departing from the ‘overly structural and static’ categories of resource mobilisation and political opportunity structures that inspired early organisational studies of civil war, recent research on social movements has developed a dynamic approach that puts interactions within movements and between movements and their opponents, especially but not only the state, at the centre of analysis.Footnote 48 In this approach, radicalisation is a process involving the adoption of extreme ideologies and/or violent means in social movements.Footnote 49 This notion is distinct from the focus on psychological mechanisms of individual radicalisation in terrorism studies and locates radical organisations within broader conflicts, including ‘the complex networks – or organizational fields – with which they interact’.Footnote 50 In a political environment characterised by different opportunities and threats, radicalisation is activated by intra- and extra-movement interactions.Footnote 51 Relational mechanisms of radical flank emergence, policing escalation, and violent outbidding, among others, are associated with these interactions.Footnote 52

The radical flank mechanism has been particularly important in research on escalation of non-violent campaigns. The Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes (NAVCO) 2.1 data reveal the presence of violent flanks, or armed wings, in most non-violent campaigns, whether these stem from a deliberate decision to adopt violent means or an inability to enforce non-violent discipline.Footnote 53 Violent flanks can, furthermore, develop inside or separately from otherwise non-violent campaigns.Footnote 54 While these flanks do not appear to systematically affect campaign outcomes, their emergence makes escalation to violent conflict more likely, especially when non-violent means fail to achieve campaign goals.Footnote 55 This finding supports the conclusion in the literature on protest cycles that political violence spreads in moments of intensified protest and increases when mass mobilisation declines.Footnote 56

Studies of clandestine political violence chart how small, underground groups in particular develop during cycles of protest. Escalating policing lies at the onset of clandestine political violence. As state and movement actors raise the stakes in response to one another, in a pattern of ‘reciprocal adaptation’, state repression backfires by attracting support to social movements, including through loyalty shifts within the regime.Footnote 57 Severe repression justifies violence and pushes militants towards clandestinity.Footnote 58 Competition for resources, from recruits to wider support, between and within movements intensifies. Movement organisations outbid each other with more radical claims and actions even if this risks provoking counter-attacks and repelling wider support.Footnote 59 In the course of competitive escalation, ‘organizations multiply and then split over the best strategies to adopt, some of them choosing more radical ones’.Footnote 60 As the momentum wanes, traditional actors regain control while radical groups continue to mobilise through militant networks.Footnote 61

Radical groups, thus, often emerge from splits in social movement organisations. But sustained armed opposition to the state becomes possible when defections from state security apparatuses in response to brutal but incomplete repression, combined with foreign support, militarise divided movements through access to military skills and weapons.Footnote 62 Militarisation further fragments the movement, including in cases where mass mobilisation unfolds in the absence of pre-existing organisation.Footnote 63 Indeed, drawing on the insight that social movements are not unitary actors but collections of factions whose views on and use of violence differ, civil war scholars have found that internal movement divisions increase the likelihood of civil war.Footnote 64 Armed organisations that emerge as a result inherit these divisions.

Movement splinters take inspiration from the organisations from which they develop.Footnote 65 These organisations vary and change over time in terms of membership, hierarchy, rule enforcement, and other elements of organisation.Footnote 66 For example, semi-splinters that movement leaders cannot rein in but tolerate form in ‘an organizational structure of weak command and control … yet can call upon the resources of a much larger and more established organization’.Footnote 67 Clandestine armed groups that break away from larger organisations start off resembling their structures, whether more centralised or networked, but become increasingly closed, hierarchical, and compartmentalised as well as prone to further splintering and infighting.Footnote 68 At their outset, however, they have access to pre-existing members and mobilising appeals, official leadership, and institutional framework. They also have organising skills and experience that helps set their organisations in motion.

This literature sheds light on the emergence of armed groups from fragmentation in social movements and the kinds of organisations that result – originally open to pre-existing members and sympathisers but increasingly limited to militants yet built on prior leadership and institutional structures that enable their activities. But not all social movements fragment as they transform into armed state challengers. Faced with an existential threat to the groups that they represent, some remain relatively cohesive and build armed groups in the course of fighting based on the leadership and membership as well as broader support that they gain before the war.Footnote 69 Others do not become radicalised or generate armed wings before the war but are ‘repurposed into militant organizations’ as the war begins.Footnote 70 In this scenario, peaceful activities of pre-war politicised opposition, which can include social movement organisations but spans beyond to political parties, kinship groups, and religious associations, among other networks, are converted into new tasks of organising for war. What armed groups emerging from social movements and broader politicised opposition have in common, however, are pre-existing bases of support, leadership, and institutions, which distinguish them from small, clandestine insurgencies that are not accompanied by concurrent social movements and cannot rely on networks of broader politicised opposition to the state at their early stages.

Peripheral challenges to the state

Recent studies of civil war have directly engaged with such ‘initial stages of rebel group formation’ that take place in remote areas and involve small groups of insurgents who lack pre-existing organisational resources, including organisational infrastructure, support from constituencies, and recruits.Footnote 71 While a vast literature exists on civil war onset, we are interested in armed group origins and focus on the relatively few studies that analyse these origins rather than civil war onset, since the two may be related but are analytically distinct. The account of peripheral armed group formation that this research develops differs dramatically from that which begins with broad-based mobilisation.

Viewing insurgency as ‘a technology of military conflict characterized by small, lightly armed bands practicing guerrilla warfare from rural base areas’, studies of peripheral armed group formation start with an observation that ‘insurgency can be successfully practiced by small numbers of rebels under the right conditions’.Footnote 72 Conditions that enable rebels to hide from state forces and weaken the reach of the central government are among them. In this account, therefore, it is not mass mobilisation fuelled by grievances that turns violent and generates rebellion by armed groups with access to pre-existing organisational resources. Instead, originally small, resource-poor groups that are vulnerable to detection and destruction by state forces become viable state challengers if they induce local civilians who are aware of the group’s formation to keep their early activities secret from the government.Footnote 73 This is more likely in ethnically homogenous rural areas outside the reach of the central government.Footnote 74 In this common setting for insurgency, kinship networks facilitate the spread and uptake of rebel rumours that generate grievances against the state and a belief in rebel capacity to challenge it.Footnote 75

Once nascent insurgencies become viable, they mobilise these networks for recruits and wider support.Footnote 76 At the initial stages of their formation, however, their leaders seek to ‘recruit and train a small, well-screened fighting force’ and build a command structure to plan and commit small-scale attacks against local state targets.Footnote 77 These groups often form in home regions of their leaders, where they recruit trusted members among family and friends. While they may have some prior military experience, their leaders lack organisational experience or skills of launching a rebellion, military resources, and external support.Footnote 78 Yet because they form in rural areas where the state is barely present and where broad-based mobilisation is also unlikely, they do not need pre-existing organisations or politicised networks to begin their activities.Footnote 79 They can build their organisations from the original small groups over prolonged periods. In contrast, so as not to be ‘quickly discovered, located, and defeated’, armed groups that emerge in the context of broad-based mobilisation require ‘an already-formed organization or pre-mobilized group from which they can draw on to clandestinely plan and quickly build organizational capacity for anti-state violence’.Footnote 80

The distinction between armed groups that form from broad-based mobilisation with pre-existing organisational resources and those that emerge as small insurgent groups in peripheral areas without such resources is an important contribution of this literature to the study of armed group origins. However, pre-war mobilisation that generates armed groups can reach even the most remote areas.Footnote 81 Such mobilisation can facilitate the emergence of small insurgent groups in the periphery when the war begins.Footnote 82 Groups of this kind, furthermore, can draw in their formation not on pre-existing organisations or politicised networks but rather patronage networks that extend far into the pre-war period and shape who leads these groups, who is recruited, and how the armed organisation operates.Footnote 83 Finally, the distinction between armed groups that emerge from broad-based mobilisation and peripheral challenges to the state overlooks armed groups that form to challenge the regime from within.

Intra-regime fragmentation

The literature on civil–military relations relevant to the study of armed group origins in civil war considers the relationship between coups d’état and civil wars, the escalation from coups to civil wars, and the emergence of military splinters in the absence of coup attempts. Taken together, this literature outlines an account of armed group origins in the context of intra-regime fragmentation.

Understanding coups as ‘illegal and overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive’ differentiates coups from other forms of anti-regime activity, including defections from the regime in the context of broad-based mobilisation and regime challenges from initially small insurgent groups that we discussed above.Footnote 84 Hence, coups should not be conflated with civil wars.Footnote 85 However, they are related to civil wars in complex ways. The likelihood of coup attempts increases dramatically during civil wars, while coups affect civil war onset, duration, and outcomes.Footnote 86 These effects depend on whether coup attempts succeed or fail,Footnote 87 the level of threat leaders face,Footnote 88 and whether the perpetrators are insiders of the ruling elite who orchestrate coups to prevent unfavourable negotiated settlements or outsiders – lower-ranking officers fighting the war – who seek to remove leaders for initiating and mismanaging the war.Footnote 89 Negotiated settlements that fail to satisfy the ruling elite similarly increase the likelihood of post-war coups.Footnote 90 In turn, post-war civil–military arrangements contribute to civil war recurrence.Footnote 91

This research shows that coups and civil wars shape one another across the war’s trajectory. Therefore, the transition from coups to civil wars is likely to present a distinctive context for armed group formation. Studies of escalation from coups to civil wars suggest that armed group origins in this context are mediated by coup-proofing.Footnote 92 Especially in authoritarian regimes, coup-proofing reduces the regime’s vulnerability to a coup but increases prospects of a civil war by undermining military effectiveness and thereby the state’s counter-insurgency capacity.Footnote 93

Counterbalancing the military with counterweights, such as executive guards, militarised police, and civilian militias, is a particularly important strategy in the escalation of coups to civil wars.Footnote 94 Autocrats’ decisions not to use these forces for counter-insurgency when they fear coups allow insurgent groups to develop in the periphery, as coup-proofing also weakens regular armies.Footnote 95 Fragmentation of security forces into different command structures as a result of counterbalancing increases the likelihood of military defections to uprisings.Footnote 96 Coup attempts in the face of counterbalancing also prompt fierce fighting between coup plotters and counterweights, as coup-installed regimes can disband the latter, which creates incentives for armed resistance. Broadening resistance to civilians turns an intra-regime conflict into a civil war in this scenario.Footnote 97 When coups succeed, counterweights act as ‘a pre-organized source of armed resistance … recruiting, training, and equipping an armed group to challenge the new regime’.Footnote 98 This lowers organisational barriers to rebellion.

Purges from the regime also generate armed resistance. Ethnic purges reduce the likelihood of a coup by members of the purged group but increase their capacity to form a rebel organisation. Purged elites become ‘dissident entrepreneurs’ who use their prior ‘experience and skills to raise the political consciousness among the excluded group, set a revolutionary agenda, and help to organize’ an armed group and their financial and military support from foreign patrons and knowledge of ‘the inner workings of their enemy … to attack the government at its points of weakness’.Footnote 99 These violence specialists’ capacity to organise private militaries from their societal base to challenge the regime feeds ‘the coup-civil war trap’, a cycle where ‘excluding rivals weakens their coup-making capabilities but at the cost of increasing the risk of civil war’.Footnote 100

But coup attempts and prevention strategies are not the only dynamics through which armed groups form in the context of intra-regime fragmentation. Scholars have distinguished ‘coup-related civil wars’Footnote 101 associated with these dynamics from ‘army-splinter rebellions’ that are not accompanied by coup attempts.Footnote 102 In this scenario, intra-elite conflicts generate factions within the military. Loss of access to political power or patronage, particularly in personalist autocracies, prompts disgruntled military elites to prepare for war. This includes organising current or former soldiers into a force outside of the army and establishing bases away from the capital. Armed groups that form as a result ‘represent existing armies breaking apart’ from the state and largely consist of military defectors at their outset.Footnote 103 They do not attempt a sudden regime overthrow and may not seek a change in government altogether but launch rebellion ‘as a warring party’, fighting the state security apparatus from which they broke apart.Footnote 104 Still, the emergence of these groups can be related to coup dynamics, as coup-proofing may prevent their members from attempting a coup instead of a rebellion.

In the context of intra-regime fragmentation, then, interactions within and between civilian and military elites that generate coup and elite splintering dynamics lie at the origin of armed groups. While military defections to uprisings have been discussed in this context, contexts of broad-based mobilisation present fundamentally distinct conflict dynamics. Here, it is not intra-regime interactions but those between and within social movements, the state’s repressive apparatus, wider audiences, and foreign actors that create dynamics of movement fragmentation and militarisation, including loyalty shifts in the regime, and repurposing of opposition from which armed groups emerge. Finally, in peripheral state challenge contexts, interactions between a small number of insurgents, local civilians, and local and central state actors underlie counter-insurgency dynamics that centre on the secrecy that armed groups require to form. These conflict dynamics in general lend themselves to different types of armed group origins.

A typology of armed group origins

How do different conflict dynamics shape armed group origins? As earlier studies of armed group formation have shown, neither pre-existing organisations nor interactions between the different actors involved in the conflict automatically translate into armed groups. Instead, ‘organizers construct new institutions and convert old organizations’ conditioned by the context in which they find themselves.Footnote 105 This places leaders of nascent armed groups at the centre of analysis of armed group origins, even where less hierarchical organisational structures emerge.Footnote 106 Leaders’ ability to deploy violence and retain control over that violence to win a war or at a minimum survive as an armed organisation, in turn, depends on how members are related to the armed group, that is, recruited, socialised, and disciplined.Footnote 107 While specific organisational structures in pursuit of these and other goals then vary, develop, and change over time, the dimensions of leadership and membership lie at the inception of armed groups.Footnote 108 Our typology, as a result, focuses on these dimensions.

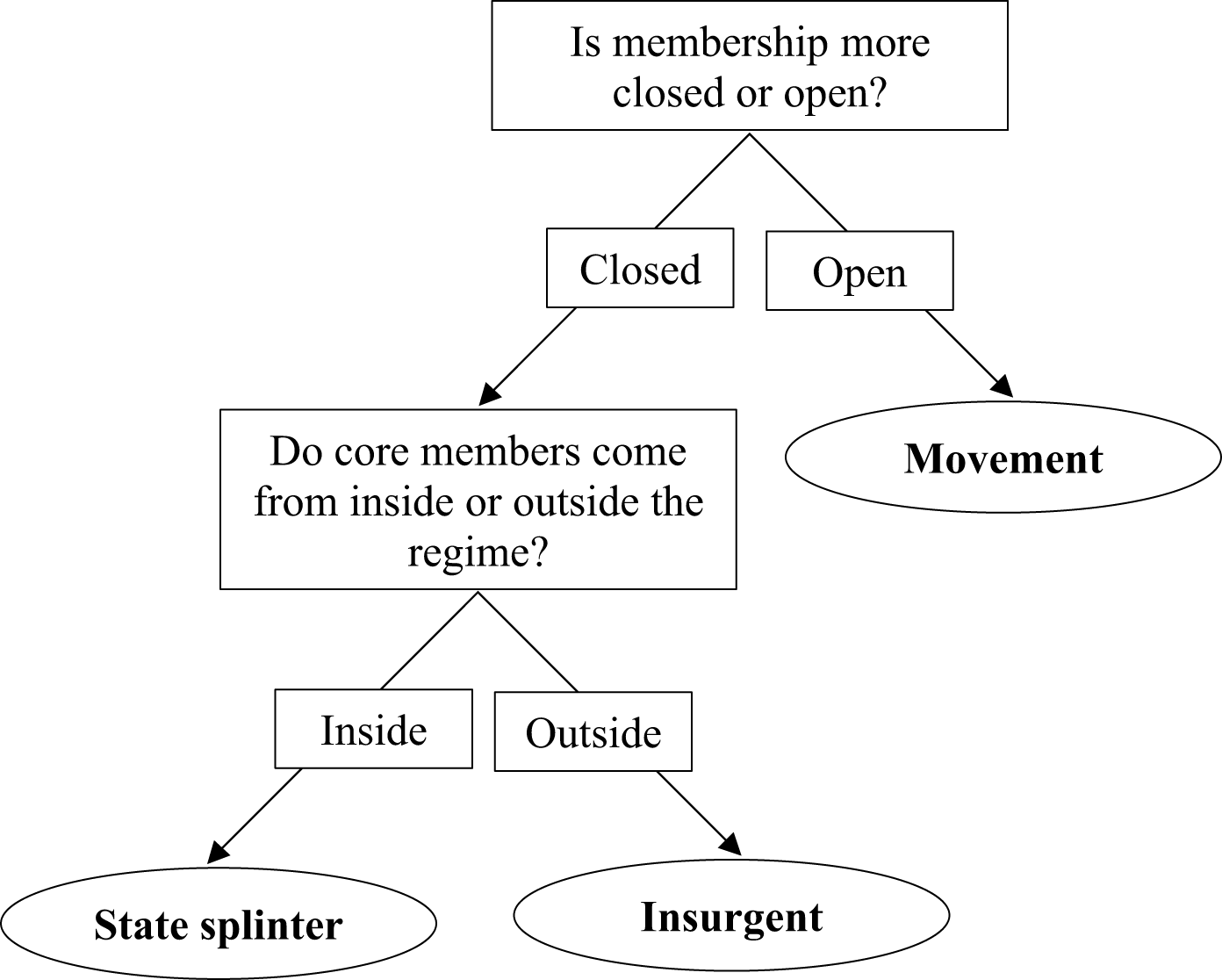

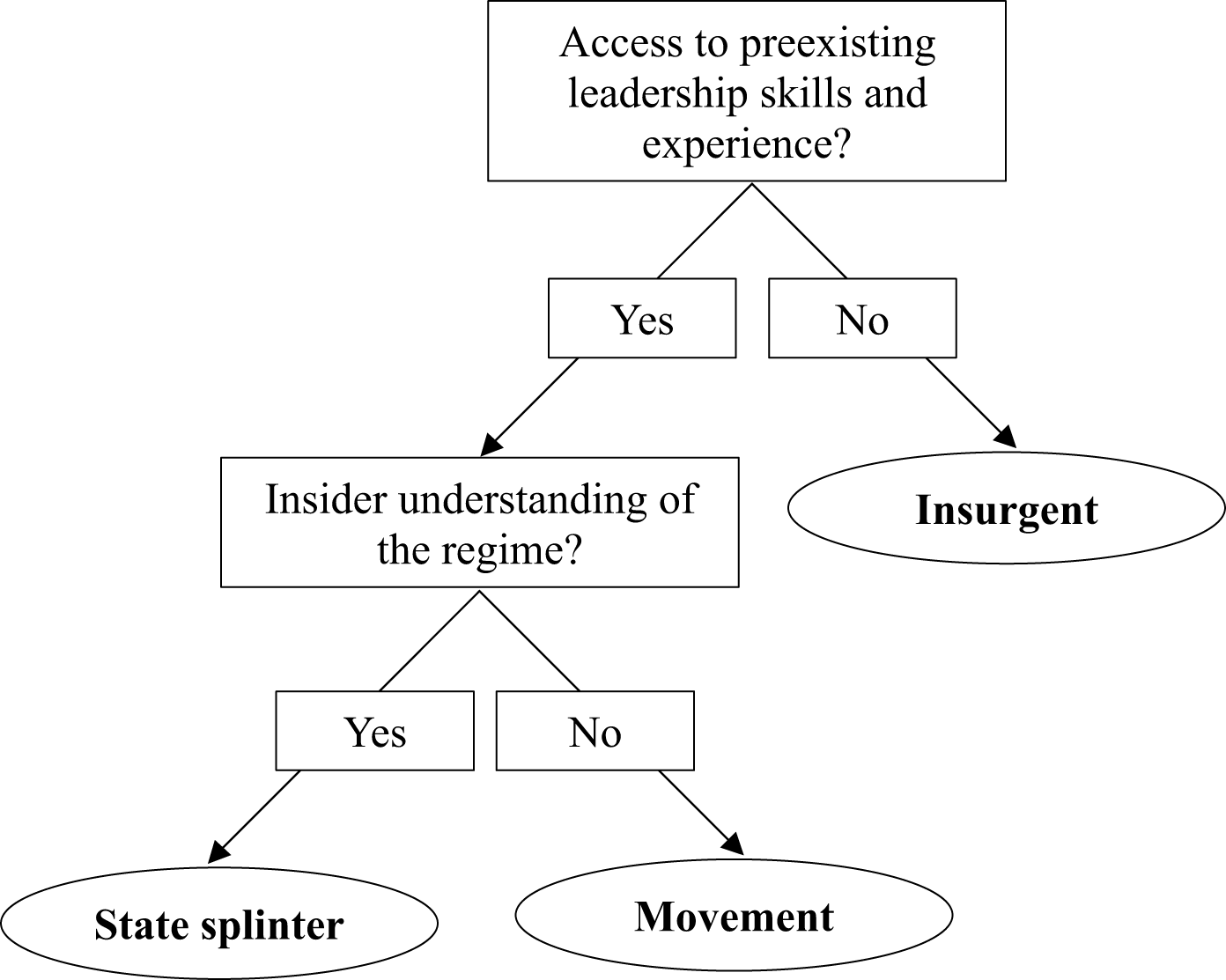

The literature review above suggests that at the most basic level armed groups at their origin are distinguished by whether their membership is more closed or open and whether the core of their members comes from inside or outside of the regime, on the one hand; and whether their leaders have pre-existing organisational skills and experience, on the other. As Figure 1 illustrates, armed groups that emerge from broad-based mobilisation, with what we call ‘movement’ origins, are in general characterised by a more open membership boundary, since members are recruited from the movement organisations and opposition networks that these groups are built on. In contrast, armed groups that form in the context of peripheral state challenges, that is, with ‘insurgent’ origins, and intra-regime fragmentation, with ‘state splinter’ origins, have a more closed membership differentiated by its basis primarily inside or outside of the regime. Early members are commonly drawn from small, trusted groups of individuals in the former and from current or former civilian government or military in the latter. Armed groups with different origins are also distinguished by pre-existing leadership. As Figure 2 illustrates, leaders of armed groups with ‘movement’ and ‘state splinter’ origins have pre-existing skills and experience related to movement organising in the former and as part of the government and/or military in the latter, whereas those with ‘insurgent’ origins generally do not. But ‘state splinter’ leaders have an insider understanding of the regime that sets them apart from ‘movement’ leaders who in general do not have such knowledge.

Figure 1. Membership.

Figure 2. Leadership.

Because organisations adapt to evolving conflict dynamics and, therefore, transform as civil wars unfold, the analytical power of our typology is temporally situated: it illuminates how different conflict dynamics shape armed group origins at the time of their formation. For example, a group that starts with a few insurgents can develop into an army and even take on a movement character. Equally, armed groups that arise in contention between civil society and authoritarian regimes can subsequently develop characteristics of groups with ‘insurgent’ origins in the face of regime crackdowns against broad-based mobilisation.Footnote 109 It is not the purpose of our typology to capture these transformations, which are contingent on wartime dynamics.Footnote 110 The membership and leadership characteristics of different types can, moreover, coexist in individual cases. For example, when defectors from the military come to lead armed groups that form in the context of broad-based mobilisation, bringing their insider knowledge of the regime to these groups, the resulting groups combine ‘state splinter’ and ‘movement’ origins. We introduce the category of ‘overlapping’ origins to indicate groups that cannot be characterised as having primarily ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, or ‘state splinter’ origins.

Despite these caveats, we believe that drawing conceptual distinctions between armed group origins can increase analytical clarity about different conflict dynamics that generate armed groups. Armed groups ‘emerge in a broader given social context, and they bear traces of earlier phases of this context’.Footnote 111 We, first, offer a way to grasp contexts characterised by fundamentally different dynamics of conflict and advance our understanding of armed group formation across these contexts. Our typology, then, serves as a useful heuristic for future studies exploring the relationship between armed groups’ emergence in these contexts, on the one hand, and how they may act subsequently, within the period between a group’s formation and its transformation, on the other. As we illustrate in the following section, for example, violence against civilians and the state that armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins engage in early in their existence differs in both scale and nature from that of groups with ‘movement’ and ‘state splinter’ origins.Footnote 112

But our typology can also elucidate broader processes of conflict, beyond specific outcomes of interest, such as patterns of violence. Appreciating different processes of armed group formation can help better understand ‘overarching trajectories of civil war’.Footnote 113 Applying our heuristic as a guide for thinking about different armed group origins can highlight elements of civil wars’ unfolding that go unnoticed in both disaggregated analyses and those of select types.Footnote 114 The dynamics of mobilisation and organisation associated with the types of origins that we outline point to distinct interactions between nascent armed groups, their domestic and foreign supporters, regimes, and other actors that are crucial to the transition from pre-war conflict to civil war and may have path-dependent continuities.Footnote 115 Interactions within movements, including their constituencies, and between movements and their opponents underlying armed groups with ‘movement’ origins, between a small number of insurgents, local civilians, and local and central state actors in ‘insurgent’ cases, and within and between civilian and military elites in ‘state splinters’ can offer access to tracing how conflicts unfold in different ways at the point of transition. The skills and experience that leaders of nascent armed groups develop in the course of these interactions and the nature and relationship of their membership to the regime also matter for the kinds of armed organisations that can be initially constructed and their ability to internally cohere, establish governance institutions in areas they control, and form alliances with other actors, among other dynamics.

To this end, we view the ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, and ‘state splinter’ types of armed group origins as broad characterisations of ‘variants of a phenomenon’, with the immediate goal of ‘making a complex phenomenon’, in our case armed group origins, ‘more manageable by dividing it into variants or types’.Footnote 116 While this can ultimately lead to theory development, we do not propose an ‘explanatory typology’, or a classification ‘based on an explicitly stated preexisting theory’.Footnote 117 Nor do we advance a ‘typological theory’ specifying and delineating independent variables into categories (e.g. ‘movement’ origin) and providing generalisations on their effects on dependent variables (e.g. conflict duration).Footnote 118 Rather, we identify broad types of armed group origins and describe their shared characteristics in a ‘descriptive typology’ where dimensions should be understood in continuous rather than binary terms, with armed groups more or less approximating extreme values (e.g. more closed or open membership) and with the possibility of overlap and change over time, as we discussed above.Footnote 119 We do so to ‘help establish similar cases for purposes of comparison … [and] spur the search for underlying theoretical explanations’ in future research.Footnote 120 This approach leaves space for further nuancing conceptualisation of armed group origins based on ‘bound comparison’ of the types that we identify and for the possibility of ‘unbound comparison’ where adaptation of existing knowledge to empirical complexity can push analytical categories.Footnote 121

Empirical illustration

So far, we have explained our decision to focus on the meso, organisational level of analysis in the study of armed group origins and have developed a typology of origins at this level building on existing bodies of literature that have addressed armed group formation in fundamentally different contexts of conflict. We have also outlined this typology’s analytic purchase, while acknowledging limitations inherent to any heuristic like ours. But how might our typology be demonstrated empirically? The next sections probe the empirical purchase of the typology. First, we apply it to an existing dataset of armed group emergence to generate a map of groups from the universe of cases according to the types that we identify. Second, we explore how our typology helps illuminate the origins of armed groups in illustrative cases.

FORGE mapping

A few datasets address the origins of armed groups.Footnote 122 Among them, the Foundations of Rebel Group Emergence (FORGE) is the largest cross-national data collection effort.Footnote 123 It includes all non-state armed groups to have reached a threshold of 25+ battle deaths per year in all civil wars from 1946 to 2011.Footnote 124 Its value to our framework lies in the detail it provides for these 428 groups’ foundational characteristics, most of which ‘drew their initial membership from some sort of preexisting named organisation’.Footnote 125 We link such ‘parental’ structures to these actors’ formation, suggesting that armed groups that emerge in contexts of broad-based mobilisation, peripheral challenges to the state, and intra-regime fragmentation will embody characteristics associated with our ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, and ‘state splinter’ types. We, thus, use the parental descent FORGE traces for all non-state armed groups to explore whether the cases included in FORGE can indeed be grouped according to our types. This is the first step in demonstrating our typology’s empirical reach.

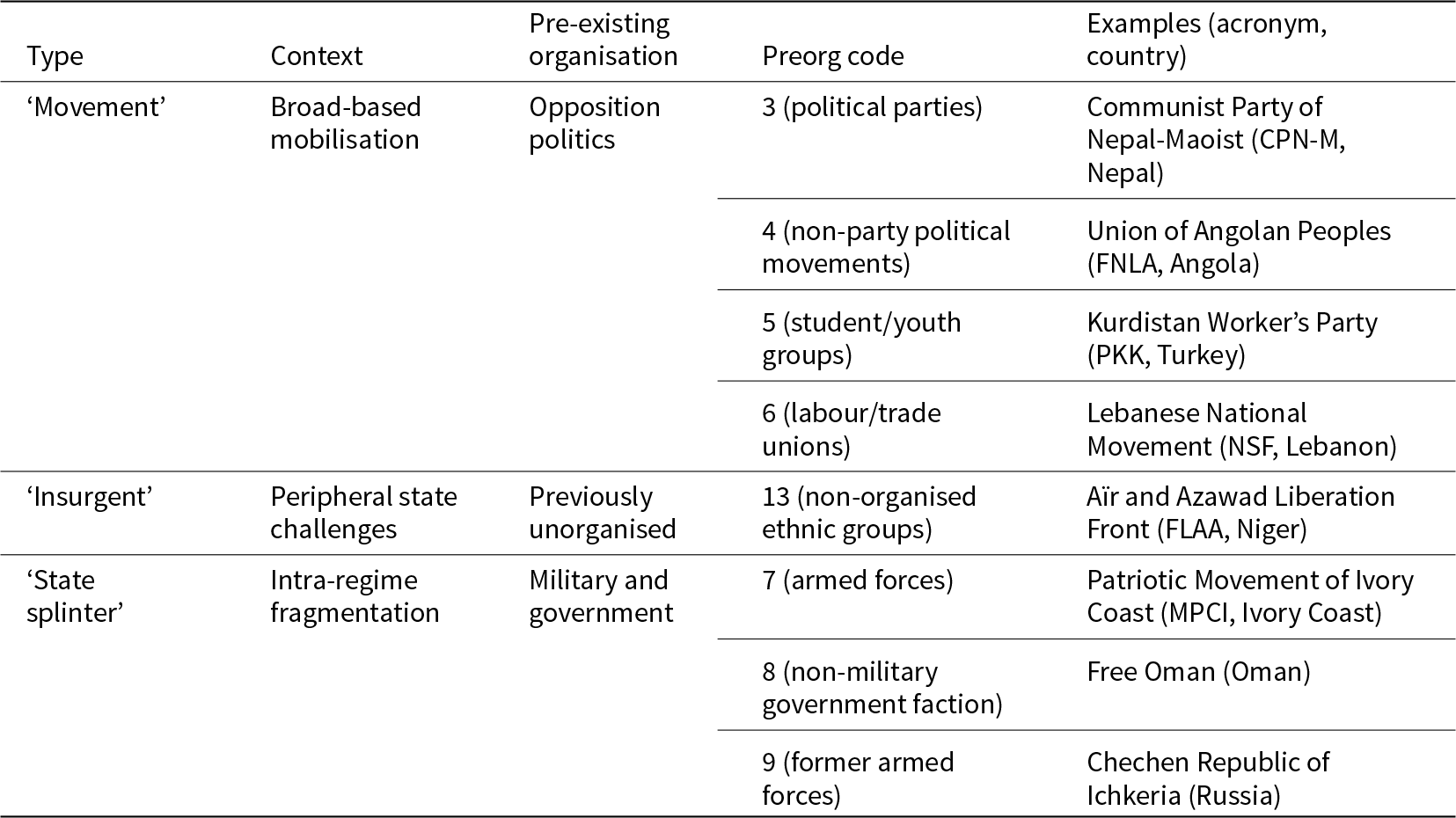

How does this work in practice? FORGE classes armed group parentage according to 14 ‘preorg’ codes. Our use of FORGE aggregates these parentage codes in three families – opposition politics ‘parents’ in the ‘movement’ family, previously unorganised groups in the ‘insurgent’ family, and military and government in the ‘state splinter’ family (see Table 1).Footnote 126 This aggregation is based on identification of actors in our discussion of conflict dynamics. Through this aggregation, we suggest that there are similarities in kind between pre-existing organisations in FORGE. For example, current and former armed forces and non-military government factions all originate inside the regime. We, therefore, argue that armed groups with these parental origins can be considered members of a ‘state splinter’ family.

Table 1. ‘Movement’, ‘insurgent’, and ‘state splinter’ origins in FORGE.

Grouping all FORGE ‘preorg’ codes in these families indicates general alignment between the accounts of armed group formation in contexts of broad-based mobilisation, peripheral state challenges, and intra-regime fragmentation and the broad types of armed group origins that emerge in these contexts. As our goal is to provide an illustration of how our types map onto the universe of cases rather than to account for all armed groups across all civil wars, we include groups involved from the start of civil wars that are the first to initiate violence of at least 25 battle deaths.Footnote 127 This selection returns the majority of armed groups that empirical studies frame as core actors in their respective civil wars and creates a focused list of 144 groups (see Appendix). Of these, 76 armed groups appear in the ‘movement’ family (52.78%); 20 in the ‘insurgent’ family (13.89%); and 40 in the ‘state splinter’ family (27.78%). A further eight groups with multiple ‘preorg’ codes in FORGE that do not conform to a single family are classified as ‘overlapping’ (5.56%). This category signals the possibility for an armed group to embody characteristics from more than one type. This mapping aligns with the earlier finding that rebellions ‘from above’, with and without coup attempts, account for at least 25% of armed groups, while those ‘from below’, which include ‘movement’ and ‘insurgent’ origins in our typology, constitute some 75%.Footnote 128 That there are few groups with ‘insurgent’ origins is also consistent with the finding that most of these groups do not survive and, therefore, do not reach the 25+ battle deaths threshold necessary to make it into cross-national datasets such as FORGE.Footnote 129

Despite its parsimony, our framework is sufficiently encompassing to reach through the universe of armed groups in FORGE in ways that existing studies support. The small number of overlapping groups left without a natural family, combined with the fact that few ‘preorg’ codes in FORGE lack an obvious family pair, indicates that, though our framework involves aggregation, it does not come at the cost of problematic abstraction from empirics. While nuance is inevitably lost in aggregating FORGE ‘preorg’ codes (e.g. distinctions between trade unions and non-party movements are lost when these organisations are placed in the ‘movement’ category), we believe our typology offers a valuable starting point for future studies on the effects of armed groups’ origins on the outcomes of interest, such as the targets and tactics of violence, and broader processes of civil war. Such future studies may inspire further refinement between our categories. For now, our typology draws out basic features for distinguishing armed groups that emerge in contexts characterised by fundamentally different dynamics of conflict.

Still, a focus on immediate predecessors, or ‘parent organisations’, can be limiting in grappling with complex histories of armed groups and leaves open the questions of how far back we should go in analysing armed group origins and what dynamics we should look for to understand how armed groups form. Decades of collective action can precede formation of armed groups.Footnote 130 In this process, ‘mobilization of some actors, demobilization of others, and transformation of one form of action into another occurs frequently’.Footnote 131 Hence, armed group formation involves dynamics of conflict that rarely follow linear paths but exhibit similarities across contexts where multiple predecessors can play a role immediately before armed group formation or further back in history. We, therefore, move beyond the typology’s application to FORGE to provide illustrative examples that capture greater complexity.

Type narratives

We now proceed to elaborate our typology in illustrative groups from each of our types. These type narratives tell us more about what our framework can help explain, with our overarching intuition being that the armed groups’ different origins have implications for the way these groups act, at least initially.

‘Movement’ origins

From the outset, armed groups with origins in social movements,Footnote 132 self-determination campaigns,Footnote 133 and spontaneous protests,Footnote 134 among other forms of broad-based mobilisation, are characterised by relatively open membership and pre-existing leadership. This applies to both groups that stem from larger social movements and those that splinter from them. The Abkhaz army that emerged during the Georgian–Abkhaz war of 1992–3, for example, has origins in the larger Abkhaz national movement. Led by the umbrella organisation Aidgylara (Unity), the movement incorporated members of this at least initially non-violent organisation, those of its violent branch and later the armed Abkhaz Guard that Aidgylara helped form, and people who were not members of these organisations but participated in the Georgian–Abkhaz conflict in everyday life and various forms of political contention, from protests to violent clashes.Footnote 135 Aidgylara promoted Vladislav Ardzinba, who was elected chairman of Abkhazia’s Supreme Council, gaining a foothold in the government of the autonomous republic. When the war began, Ardzinba openly framed the advance of Georgian forces into Abkhazia as a threat from his position as the Abkhaz leader.Footnote 136 Members of Aidgylara and local authorities active in the struggle mobilised the defence force in public gatherings across the republic and ‘house to house’.Footnote 137 People with and without prior membership in the movement joined the force, which was initially loosely organised on the basis of pre-existing networks and organisational skills and Soviet military experience.Footnote 138 During the war, it transformed into an army with foreign support and achieved a military victory that paved the way for the establishment of a de facto state. Yet, at its outset, this force was based on open membership and pre-existing leadership.

Relatively open membership and pre-existing leadership also lie at the origin of armed groups that stem not from larger movements but their factions. In El Salvador, for instance, the factions that formed the Farabundo Marti Front for National Liberation (FMLN) in the context of mass social movement mobilisation ‘recruit[ed] university and secondary school students in urban areas and campesinos in rural areas’ and included ‘significant numbers of erstwhile protestors’.Footnote 139 Their leaders were initially outsiders – university students and professionals who engaged in opposition politics in the early 1970s.Footnote 140 But as repression intensified in the late 1970s, membership expanded.Footnote 141 The FMLN emerged in 1980 on the basis of this open membership and coordination capacity of the different factions’ leaders. The organisation turned into an army and after the war a political party underpinned by a collective identity and the legitimacy of the collective action against injustice of which it was part.

More commonly, however, armed groups that splinter from social movements or emerge from broad-based spontaneous protests are characterised by fragmentation, even though they have access to pre-existing membership and leadership. Armed splinters that drew existing members and leaders from the Palestinian national movement in the conditions of weak central control and command rarely enjoyed broad popular support.Footnote 142 In turn, external support directed their activities away from the self-determination struggle, with competition between rival groups preventing the movement’s leadership from achieving common goals through non-violent means and destabilising the broader movement. Similarly, in Libya, the spontaneous protests that erupted in 2011 and grew in response to brutal state repression, which triggered high-level defections from the regime, resulted in the creation of the National Transitional Council (NTC) to represent all regions of Libya with ‘a political leadership and channels to foreign governments’.Footnote 143 But this leadership was fractured and poorly organised, and armed groups that proliferated locally escaped its oversight.Footnote 144 Without central coordination, rival groups competed for resources, and the NTC was unable to direct their activities towards common opposition against the regime.Footnote 145

Hence, armed groups with ‘movement’ origins can advance common goals when movements are adapted to the needs of armed struggle. Yet most inherit organisational weaknesses and divisions within social movements composed of multiple factions and conflicting interests and are plagued by continuing fragmentation. While future research should explore these diverging outcomes in cases of armed groups with ‘movement’ origins, our purpose here is to distinguish these groups from those with other types of origins. This distinction is evident when comparing these groups that rely on pre-existing organisational resources to those with ‘insurgent’ origins that in general lack such resources.

‘Insurgent’ origins

Armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins at their outset are characterised by a more closed membership, where a boundary exists between those inside and outside of the group, than those with ‘movement’ origins. Their leaders do not have pre-existing experience or skills of organising opposition to the state. Most of these groups fail before becoming viable threats to the state due to the initial power imbalance between these groups and the state.Footnote 146 But some of the most notorious armed organisations share these origins. The Revolutionary United Front (RUF) emerged in the context where the Sierra Leonean government violently repressed civil society in cities but did not have the reach to monitor and respond to potential threats in the periphery.Footnote 147 The group had at its core a small number of trusted members with few weapons and ‘minimal external support’.Footnote 148 Three men from among the exiled radicals and university students who acquired some military training in Libya formed a close-knit group, first in Freetown and then rurally, which set the RUF-to-be in motion a few years before its first attack in 1991.Footnote 149 The group lacked organisational experience and skills, as the ‘disenfranchised and politically active’ contingent that could have provided such skills left early on.Footnote 150 Yet, because of the military’s weakness, it ‘did not need to be overwhelmingly powerful’ to survive and shifted to guerrilla tactics in mid-1990s before its demise in 2002.Footnote 151

Indeed, armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins often start by perpetrating low-scale violence against ‘easy’ state targets, which signal their ability to challenge the state to their potential bases of support. Made up of Joseph Kony’s schoolmates and friends, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) of the late 1980s engaged in infrequent attacks that were not highly lethal, for example, ‘ambushes of police barracks and small military detachments’ where the groups’ weapons initially came from.Footnote 152 These attacks informed local civilians of the group’s goals through a network Kony previously built as a traditional healer.Footnote 153 Local communities’ silence about the group’s whereabouts and activities enabled it to maintain secrecy vis-à-vis the state, as did its early closed membership of approximately two dozen ‘devoted followers, from [Kony’s] home area’.Footnote 154 When they rely on civilians for secrecy in the face of discovery and crackdown even by weak states, these groups are initially disciplined in their limited use of violence against civilians. Even the LRA, known for gruesome violence against civilians, rarely committed such violence in its early days.Footnote 155

As these groups gain access to resources that reduce their reliance on the population, for example, through external support, they turn on civilians.Footnote 156 In Uganda, no nascent group, including the LRA, received external support before becoming viable.Footnote 157 This is in line with the finding that moderately strong groups are likely to be supported externally.Footnote 158 The group’s early discipline in relation to civilians contrasts with its increasingly violent behaviour once it obtained substantial support from Sudan.Footnote 159 In turn, the RUF did not rely on popular support but received limited if inconsistent assistance from Charles Taylor in Liberia.Footnote 160 Division in the RUF between Sierra Leonean and Liberian fighters from the NPFL was one of the reasons the group engaged in brutal atrocities from early on.

This suggests that access to different forms of resources is crucial for these initially small, poor groups’ development. At the outset, however, they generally lack such resources, and their membership and leadership reflect their weakness and the secrecy that they require to survive in the initial stages of their formation as a result. This contrasts with armed groups that have pre-existing access to resources due to their ‘movement’ and ‘state splinter’ origins. However, whereas groups with ‘movement’ origins do not generally have an insider knowledge of the regime at the outset, those with ‘state splinter’ origins do. Moreover, while their membership is initially defined by their background in government and/or military and is, therefore, similar to groups with ‘insurgent’ origins in being more closed than in ‘movement’ cases, the nature of this membership is distinct.

‘State splinter’ origins

What distinguishes armed groups with ‘state splinter’ origins is that their membership and leadership come from inside the regime. This direct relationship to the state differs from the need for secrecy vis-à-vis the state in ‘insurgent’ cases and the role of state repression and defection from the regime in groups with ‘movement’ origins.Footnote 161 Members of ‘state splinters’ are current or former civilian government or military personnel. This background defines the border between those in and out of the group. This border is initially fixed by the pre-existing composition of the state bodies from which these groups emerge. Their leaders have experience and skills acquired in the regime. They enjoy existing sources of internal and external support and unique access to military resources that groups with ‘insurgent’ and ‘movement’ origins do not, at least to the same extent. Their military members are specialists in violence, which enables them to organise their activities with the knowledge of the regime and of warfare.Footnote 162 The ability of Riek Machar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Army-in-Opposition (SPLA-IO) to capture strategic sites early in the fighting that began in 2013 in South Sudan demonstrates this organisational advantage of groups with ‘state splinter’ origins as compared to those with ‘insurgent’ and ‘movement’ origins. Unlike in ‘insurgent’ cases, for example, where ‘a small group of dedicated activists rally public support around a budding insurgent cause’, in SPLA-IO, as in its predecessor SPLA, ‘military capacity was present at birth’.Footnote 163 The commander of the South Sudan Army’s 8th Division who joined the ‘state splinter’ captured the strategic city of Bor, and others deserted elsewhere.Footnote 164 The government soon lost control of three states but received support from Uganda’s military to attack Machar’s forces and hold the capital Juba.

The SPLA-IO is a particularly important illustrative case as it straddles the distinction between coup-related ‘state splinters’ and those that develop without coup attempts. Machar was accused of attempting a coup, but a purge of those loyal to him from the regime could as well have brought about the splinter. Machar could not ‘seize power from within’, a result of coup-proofing.Footnote 165 But his previous experience and skills enabled him to mobilise internal and external support, access military resources, and attack the state where it was weak. In SPLA-IO, as in coup-related cases, ‘leaders of the fighting parties on both sides [were] members of the government’.Footnote 166 Such leaders can ‘leverage their access to state resources and existing patronage networks to better organize and fund rebellion’.Footnote 167 But SPLA-IO had at its core excluded and deserting members of the state who were losing access to political power and patronage, as in groups that do not attempt coups.Footnote 168 Exclusion reduces such groups’ access to resources, even though some patronage networks persist.Footnote 169 Still, excluded groups’ leaders have experience and skills to mobilise and organise from the excluded group.Footnote 170 They also do not have to invest extensively in training, particularly of military members who have prior training as part of the state armed forces. Then vice president of South Sudan, Machar’s ability to recruit from within his social base, putting ‘a significant part of the country in open rebellion’ when president Salva Kiir threatened his exclusion from the regime illustrates this.Footnote 171

Hence, while the stakes for coup plotters are especially high – ‘the consequences for being on the losing side of a coup attempt can be dire’ – the ‘state splinter’ origin of members and leaders in both coup- and non-coup-related cases offers these armed groups an advantage in terms of organisational and military experience and skills.Footnote 172 As a result, these groups can access not only state resources, being initially ‘armed to a great extent by the state itself’, but also those from ‘foreign patrons whose financial and military support is often indispensable for the group to sustain a private army’.Footnote 173 For example, Charles Taylor, who supported the coup of 1980 led by Samuel Doe in Liberia and was part of the government, later formed the NPFL with other regional exiles, exploiting existing domestic and foreign patronage networks of the regime.Footnote 174 The ties he cultivated with economic allies as an insurgent ‘were predicated on … [their] assumption that he would win the war and become ruler of a sovereign state’.Footnote 175Combined, the forces of Samuel Doe and NPFL incorporate elements of ‘state splinter’ and ‘insurgent’ origins and could, thus, be viewed as an ‘overlapping’ case. Yet the ‘state splinter’ aspect of NPFL’s origins and its associated access to resources aided its transformation from a small initial core into a large army.

Whereas the NPFL undertook this transformation, armed groups that emerge from within the state apparatus commonly fragment by recruiting members beyond the original core of the group who do not have pre-existing experience in the regime and by diversifying its leadership. For example, divisions within the SPLA-IO characterised its opposition to the regime as the group mobilised a diverse force with varied local leadership in the course of the war. Future research should further consider this implication of ‘state splinter’ origins.

Future research

Armed groups, therefore, differ substantively based on whether they have ‘movement’, ‘insurgent’, or ‘state splinter’ origins. These different ways in which armed groups form have implications for their early relations, not least with the state. For example, armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins, because of their small size and power imbalance vis-à-vis the state, are likely to engage government forces indirectly and employ guerrilla tactics, at least at first. In contrast, coming from within the regime, with the resources and knowledge about the state that this entails, armed groups with ‘state splinter’ origins can face government forces directly, using conventional tactics, particularly when they emerge from the current military. Groups with ‘movement’ origins will fall in between and use guerrilla or conventional tactics, or a combination of both, depending on whether they grow out of entire social movements or their factions and the kind of support that they receive. Future work should examine whether and under what conditions armed groups with different origins adopt distinct tactics given the important consequences of these ‘technologies of rebellion’ for the severity, duration, and outcomes of civil wars.Footnote 176

Indeed, existing studies have pointed to the different severity and duration of conflicts involving armed groups with different origins, even though this research has generally looked at outcomes at conflict rather than armed group level and focused on one set of origins or grouped the origins that we distinguish. For example, rebellions that are not accompanied by coup attempts, which we include in ‘state splinter’ origins, are bloodier and shorter than those from below – ‘insurgent’ and ‘movement’ cases, in our framework.Footnote 177 They are characterised by conventional warfare and are likely to be more severe in terms of battlefield than civilian deaths.Footnote 178 In turn, civil wars that emerge from coups, which are also among ‘state splinters’, and revolutions, which are part of our category of ‘movement’ origins, are relatively short, and the overall casualties are significantly lower as compared to other civil wars, especially prolonged ones involving armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins that manage to survive and continue their activities despite their power asymmetry in relation to the state.Footnote 179 This finding may be due to exclusion of recent cases, particularly the Syrian Civil War, where ‘movement’ origins of armed groups, and the fragmentation that we associate with these origins, may have contributed to the war’s long duration and brutality, especially civilian victimisation. Further research is needed to reconcile these different findings within and across the categories.

Careful attention to the distinct logics of armed groups with different origins and their transformation over time can help achieve this goal. As we outlined, for example, armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins that commit limited violence against civilians because of their reliance on local communities in their early days can evolve into brutal armies that victimise populations. Understanding these groups’ broader histories can also help illuminate a range of other conflict outcomes beyond tactics, severity, and duration. One question that this approach can help answer is why some armed groups form alliances or compete with each other whereas others limit their connections. For example, armed groups with ‘insurgent’ origins, because of their need for secrecy vis-à-vis the state, might not seek alliances or even compete with other non-state armed actors operating in the same area, instead staying under the radar, at least at the outset. This is in contrast to those with ‘movement’ origins that operate openly in opposition to the state and develop in parallel with other actors, either formally or informally. Another question is war-to-peace transitions. For instance, ongoing fragmentation of armed groups with origins in fragmented social movements can translate into the inability of these groups to form a unified stance in relation to the state and unstable post-war arrangements, if any.

This discussion shows that we need to not only disaggregate armed group origins and grasp the logics behind groups that form in different ways but also analyse what a given armed group looks like at any point during the conflict in order to draw time-specific conclusions for conflict outcomes or develop informed policy responses. The approach to armed groups that centres on the impact of varied armed group origins on these groups’ internal and external relations and the changes in these relations over time can help better understand the dynamics behind conflict outcomes. This processual approach invites a qualitative comparative research agenda where armed groups with distinct origins are considered in comparison through an in-depth analysis of these groups’ complex histories.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210524000020.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship (Grant Title: ‘Understanding Civil War from Pre- to Post-War Stages: A Comparative Approach’; Grant Reference: MR/T040653/1; start date 1 January 2021). We would like to thank participants in the Civil War Paths expert workshop, including Joel Blaxland, Jessica Maves Braithwaite, Henk-Jan Brinkman, David Cunningham, Christopher Day, Véronique Dudouet, Adrian Florea, Yvan Guichaoua, Wolfram Lacher, Florian Weigand, Joseph Wright, and Marie-Joëlle Zahar, the Civil War Paths research team – Eduardo Álvarez-Vanegas, Hanna Ketola, Toni Rouhana, and Sayra van den Berg – and fellows of the Centre for the Comparative Study of Civil War for insightful comments on earlier drafts. We also benefited from engagement with the article at annual meetings of American Political Science Association, British International Studies Association, and Conflict Research Society and research seminars at University of Bath, University of Oslo, Yale University, and Geneva Graduate Institute, including discussant comments prepared by Danielle Gilbert and Bilal Salayme. We are grateful to Theodore McLauchlin and Jennifer Welsh for helping us clarify the intra-regime fragmentation aspect of our framework at the Université de Montréal and to Gilles Dorronsoro and the research team of the European Research Council Social Dynamics of Civil Wars project for earlier collaborative efforts to theorise armed group origins. Constructive feedback and guidance of the editors and three anonymous reviewers greatly strengthened the article in the process of publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this article is available in Appendix: FORGE Mapping under Supplementary Materials and is based on the Foundations of Rebel Group Emergence (FORGE) Dataset released in Jessica Maves Braithwaite and Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, ‘When organizations rebel: Introducing the Foundations of Rebel Group Emergence (FORGE) Dataset’, International Studies Quarterly, 64:1 (2020), pp. 183–193.