The biopsychosocial model (BPSM) originates from two articles published by George EngelReference Engel1 in 1977 and 1980 who was dissatisfied with the prevailing biomedical model that he perceived as excessively reductionistic. Engel was a gastroenterologist who had undergone psychoanalysis, and his proposed model was aimed at medicine generally, but primarily became influential in psychiatry. Engel proposed that the biomedical model, in exclusively considering processes below the level of the individual's psychological and social circumstances, was ‘critically ignorant’. Thus, even a perfect understanding of changes in neurobiology associated with a given mental disorder, such as depression, could miss important aetiological factors of these changes such as bereavement, loss of job, bankruptcy. Also, widely recognised psychological processes bear relevance to health and the healing process, such as the placebo response, treatment-seeking and adherence. Engel's BPSM sought to re-establish the importance of psychosocial factors to clinicians.

Engel's primary aim was unifying psychoanalysis with biomedicine. He emphasised cases where solely biomedical approaches would fail to direct good clinical care but made no serious attempt in conceptually defining the bio, psycho or social levels of his model. This uncertainty has left the BPSM open to serious criticism by both philosophers and physicians.Reference Roberts2 The critics claim the BPSM is vague, non-prescriptive, lacking in scientific content and offers no specific guidance to clinicians, who can arbitrarily focus on the bio, psycho or social as they see fit. This leads to a state of ‘unprincipled eclecticism’ or ‘wayward BPSM discourse’.Reference Roberts2

Hence, dissatisfaction with the dominant biomedical paradigm because of excessive reductionism is yet to be resolved owing to the vagueness of the BPSM, which has hardly advanced since Engel's original proposal, with rare exceptions.Reference Bolton and Gillett3 A recent attempted update by Bolton and GillettReference Bolton and Gillett3 recognised that biological forms differ from the objects of chemistry and physics by being meaningfully ascribed with functions, but missed the critical dynamics that shaped those functions via appropriate biochemical reactions and systems that maintain life-forms: their importance for the survival and reproduction of that organism. Natural selection is widely recognised by evolutionary biologists and psychologists as shaping the systems of concern to medicine and psychiatry. If the BPSM needs updating to become more scientifically coherent, we suggest that the application of evolutionary thinking is an ideal next step to enhance Engel's model.Reference Hunt, St John-Smith, Abed, Abed and St John-Smith4,Reference Hunt, St John Smith and Abed5

Evolutionary medicine and Tinbergen's four questions

Evolutionary medicine and evolutionary psychiatry are scientific disciplines applying principles from evolutionary biology to understand health and disorder. While Engel emphasised the importance of understanding imminent causation at the biological and psychosocial levels, evolutionary perspectives can further ask about vulnerability to disease at the evolutionary level – why have evolutionary processes not prevented the disease from occurring, and what adaptive systems are involved or going wrong? We agree with Steven Pinker that evolution is the link in the explanatory chain that connects human thoughts and emotions to the laws of the natural world. Thus, evolutionists can borrow from the fundamental theory of evolution by natural selection, essential for explaining biological variation, further applying it to those aspects of biological variation making humans vulnerable to conditions such as mental disorders or illness.

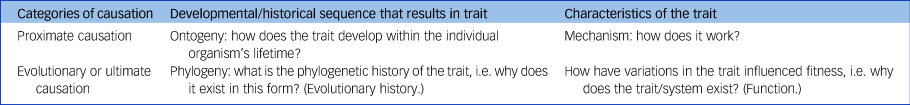

In evolutionary biology, ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen's ‘four questions’ (expanding upon Ernst Mayr's earlier proximate/ultimate causation distinction) are widely recognised for their systematic asking of distinct questions about causation from within the framework of evolutionary theory. In understanding the cause of an animal's behaviour, we can ask about its precipitating psychological and neurological state, its developmental history and experiences, the adaptive function of relevant behaviours and the phylogenetic roots of the behaviour. Tinbergen thus distinguished proximate questions of mechanism and development (the answers to ‘how’ questions) from ultimate questions of phylogeny and function (the answers to ‘why’ questions) (Table 1).

Table 1 Tinbergen's four questions

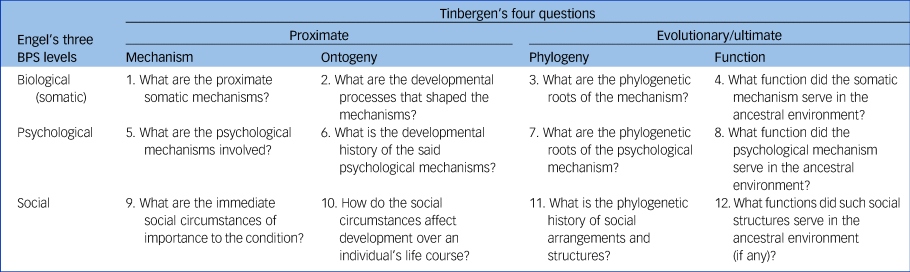

Most importantly, all four questions can simultaneously be asked of all biological systems – including dysfunctional systems – to understand a given trait at multiple levels at once. This could provide a critical dimension of insights for expanding the medical model beyond Engel's BPSM. We have proposed this allows us to formulate an ‘evobiopsychosocial model’ (EBPSM) (Table 2).

Table 2 Twelve evobiopsychosocial model questionsa

BPS, biopsychosocial model.

a. Adapted from Hunt et al.Reference Hunt, St John-Smith, Abed, Abed and St John-Smith4

The EBPSM

The three levels of analysis noted by Engel's BPSM can each be more deeply understood with Tinbergen's four questions.Reference Hunt, St John-Smith, Abed, Abed and St John-Smith4,Reference Hunt, St John Smith and Abed5 Combining these parallel frameworks results in a three by four table with 12 cells (Table 2).

Biomedical approaches ask questions of biological (or ‘somatic’) mechanism and ontogeny. Engel expanded analysis upon the psychological and social dimensions but did not place them within a comprehensive framework. The EBPSM first clarifies how the BPSM levels relate to each other: despite nominal separation, all three of Engel's levels have a significant biological component – clearly the mechanisms mediating effects at the ‘psycho’ and ‘social’ levels are functional biological systems, and psychosocial interventions are effective because of their downstream effects on somatic factors. Also, it draws attention to the fact that biological adaptations can evolve at multiple levels, beyond the somatic. The evolutionary questions add critical context elucidating this relationship: the biological, psychological and social factors had evolutionary functions over our phylogenetic history, which explains their present form.

Benefits of EBPSM over Engel's original model

Providing a more coherent, scientifically complete and philosophically sound model of medicine, the EBPSM has specific practical benefits for understanding and improving medical research and practice.

One major insight arising from the evolutionary perspective relates to the propriety of using specific animal models in psychiatry. Current non-evolutionary approaches pay scant attention to the importance of phylogenetics and function. Animal models are often selected based on surface similarities between certain animal behaviours and features of mental disorders in humans.

For example, animal models of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) focus on features of compulsive behaviour, stereotypy and perseveration in mice and rats,Reference Alonso, López-Solà, Real, Segalàs and Menchón6 but whether this reflects the same dysfunction involved in OCD in humans is questionable. An evolutionary perspective endorses the utility of animal models to the extent that the system in question is phylogenetically conserved, serves similar functions and is shared between species. For fundamental emotional responses such as fear or anxiety, laboratory rodents may be useful animal models. For more complex emotional and cognitive states related to recent evolutionary pressures (for example related to pair bonds, complex social structures or language), rodent models are likely to be much less useful, and more closely related species such as primates may be more appropriate. Phylogenetic distance between the specific system under investigation is a key factor, almost entirely missing from modern medical research.

A further critical benefit of adopting evolutionary approaches to psychiatric problems is in expanding upon the benefits of holistic perspectives that Engel endorsed. For example, depression is often clearly biopsychosocial – somatic differences in brain function, debilitating psychological processes and social factors are simultaneously relevant. However, the additional evolutionary perspective asks important questions about those biopsychosocial factors. What is the function of the mood system that may be dysregulated? Are there unusual modern environmental factors (for example social isolation) – so called ‘evolutionary mismatches’ that may be causing the dysregulation of that system? Such questions offer novel directions for identifying harmful social environments by contextualising the depressed mood as a psychological state arising within a very different environment to that in which it originally evolved.

Unlike Engel's BPSM, the evolutionary approach fully contextualises human psychological functioning within the environment it was designed to function within. Hence, the EBPSM encourages practical holism with crucial additional scientific information relating to human evolutionary history. This should enhance the framing of clinical research questions, for example by subtyping patients (for example who are depressed) by evolution-informed environmental variables to consider whether symptom clusters and treatment responses differ depending on environmental causes. We also suggest that evolutionary understanding automatically makes clinicians less reductionistic in dealing with patients and can help foster improved clinician–patient empathy and understanding of the problems being faced. Indeed, recent evidence has shown that evolutionary explanations of depression help reduce self-stigmatisation in patients.

The EBPSM and evolutionary perspectives more generally offer enhancements to both psychiatric training and practice. Trainees could benefit greatly from an early, fairly simple grounding in evolutionary theory and its consequences for understanding psychiatric conditions, providing a robust theoretical framework for the variety of conditions and symptoms they will encounter,Reference Abed, Ayton, St John-Smith, Swanepoel and Tracy7 as well as a principle for connecting the various perspectives referencing the biological, psychological and environmental factors that are currently taught.Reference Hunt, St John-Smith, Abed, Abed and St John-Smith4,Reference Hunt, St John Smith and Abed5 Early basic evolutionary education should clarify how these different approaches relate to each other coherently. This would potentially simplify the learning of what previously looked like disparate and disconnected facts.

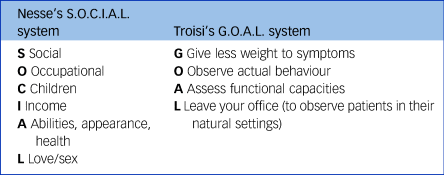

In clinical practice, the evolutionary perspective underlines the importance of asking questions regarding social and environmental context. It also directs attention to the primacy of patients’ real-life functional capacity over symptom counting. Examples of evolutionarily guided clinical assessment includes Nesse's S.O.C.I.A.L.Reference Nesse8 and Troisi's G.O.A.L.Reference Troisi, Abed and St John-Smith9 systems (see Table 3). These integrations could enhance trainee comprehension and scientific understanding and provide enhanced structures for clinical work, with downstream effects on clinician and patient understanding and outcomes.

Table 3 Nesse's S.O.C.I.A.L. and Troisi's G.O.A.L. systems

Conclusion

The neglect of evolution leads inevitably to an incomplete understanding of causation in medicine and psychiatry. Although Engel's BPSM was undoubtedly an advance over an excessive biomedical model, it lacked sufficient grounding in the biological sciences. The EBPSM aims to remedy this and offers the scope for a richer, comprehensive and more integrated research programme that overcomes the current separation between the biomedical sciences and the psychosocial research agendas. Although evolutionary medicine and evolutionary psychiatry are young fields, and the EBPSM should be treated as similarly preliminary, we propose that even in its current state it can help draw attention to areas of causation that would otherwise be overlooked, can help generate important novel research questions, encourage education and offers a pathway to a more scientifically sound medical model, which can benefit from the broad empirical and theoretical successes of the evolutionary sciences.

The advantages of the EBPSM can be summed up as follows.

(a) Embeds the BPS firmly within the life sciences, providing a solid scientific grounding.

(b) Combines Tinbergen's four causal domains with the BPS's three levels provides the opportunity to uncover processes and levels of interaction that otherwise remain hidden.

(c) Facilitates education by organising information logically.

(d) Identifies novel avenues for theorising, research and interventions on disease and disorder in diverse areas of medicine including mental health.

(e) Reduces the stigma of mental disorders and treatment.

(f) As is the case with all scientific constructs, the EBPSM is work in progress but holds the promise of important insights and practical clinical, educational as well as research applications.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

R.A. wrote the initial draft and A.H. and P.S.J.-S. amended and edited further drafts. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.