Introduction

In 1951, Claude Cahen, frequently remembered for his pioneering work on the Crusades and the Seljuks of Rum, published in Journal Asiatique an extensive discussion of the origins of the beyliks (emirates, principalities) of Denizli, Karaman, and Germiyan, three of the most significant emirates to succeed the Seljuks of Rum in fourteenth-century central and western Anatolia.Footnote 1 As hinted at in the paper's title – Notes pour l'histoire des Turcomans d'Asie Mineure au XIII siècle – and in Cahen's conclusions, the article consisted of a series of thought-provoking, but nonetheless preliminary, “notes”, observations, and hypotheses.Footnote 2

Cahen wrote his Notes amid of a wave of renewed academic interest in the origins of the beyliks. Such a trend was fuelled, throughout the 1930s and beyond, by a series of articles and debates opposing, among others, Mehmet Fuat Köprülü and Paul Wittek. Köprülü and Wittek, at the time the two uncontested heavyweights of Seljuk and early Ottoman studies, did much to develop the history of the beyliks, even though most of their opposition revolved around the nature of the early Ottoman state.Footnote 3 In the 1940s and 50s, the young Cahen, who had received his doctorate in 1940, followed in Köprülü and Wittek's footsteps and embarked upon a journey that led him to bring scholarly understanding of the beyliks to a new level.

Most of the hypotheses developed by Cahen in his Notes were received enthusiastically and have stood the test of time. However, the last section of his essay, a six-page analysis dedicated to the origins of the Germiyanid beylik (l'origine des Germiyan), stirred much controversy. While discussing the ethno-cultural make-up of the people living within the boundaries of the Western Anatolian Germiyanid emirate, Cahen stumbled upon an intriguing testimony left by Ibn Battuta in which the North African traveller describes the Germiyanids as descendants of Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya, the second Umayyad caliph (r. 680–683).Footnote 4 Following the trail left by Ibn Battuta, Cahen proposed to locate the homeland of the Germiyanids in the Kurdish inhabited regions of Eastern Anatolia. As such, Cahen concludes, the Germiyanids may have counted among their ranks, besides a strong core of Turkmen warriors, a significant proportion of Yezidi–Kurdish tribesmen, an ethno-religious group often castigated by contemporary Muslims for their “excessive” worship of Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya.Footnote 5

In Turkey, where the nationalist school of history held the Anatolian beyliks as the epitome of a “pure” Turkish ethos and antithesis to the Persianized Seljuk and Ottoman dynasties, the possibility of the Germiyanids being a “mixed” Turkish–Kurdish beylik received a very cold reception. Among Cahen's harshest critics was Mustafa Çetin Varlık, a prominent expert on the Germiyanids, who severely criticized Cahen's methodology and rejected his hypotheses as baseless conjecture.Footnote 6 In Europe and North America, the Notes drew the attention of Barbara Flemming, a German Ottomanist, who prudently deemed such theories to be “conceivable”, considering the diverse and confederational nature of the Anatolian beyliks.Footnote 7 Aside from these rare exceptions, Cahen's theories on the nature of the early Germiyanid beylik were more often than not accepted without further consideration. Hence, to this day, the Germiyanids are usually described as a mixed Turkish–Kurdish beylik in most encyclopaedias and surveys on the Seljuks, the Ottomans, and Byzantium.Footnote 8

Seventy years after the publication of the Notes, and with the benefit of hindsight provided by seven decades of scholarship, one can easily grasp the shortcomings of these two approaches. First, Cahen originally framed his conclusions as tentative hypotheses. In his magnum opus, La Turquie pré-Ottomane, the French scholar tempered his early thoughts and prudently concluded that the Germiyanids were perhaps (peut-être) of mixed Turkish-Kurdish origin, a far cry from the less cautious approach found in European and North American surveys and encyclopaedias.Footnote 9 On the other hand, the primary concern of early Republican Turkish scholars was to write a Turkish-centric history of Anatolia for the young Turkish nation, an endeavour akin to the “Roman National” cherished by nineteenth-century French nationalists.Footnote 10 While it is true that historians such as Köprülü did much to improve our understanding of medieval Anatolia, their attempts to write a Turkish Roman National left little space for the history of the non-Turkic people of Anatolia, among them the Kurds, and for the possibility of the Germiyanids being anything but “pure” Turks.Footnote 11 Finally, from a more contemporary perspective these two approaches suffer from a further flaw: scholarship on the history of the Germiyanids has been somewhat lacking since the publication of Germiyan-oğulları tarihi (The History of the Germiyanids) by Varlık in 1974.Footnote 12 To date, our knowledge and understanding of the early Germiyanids remains too limited to take a strong stance for or against Cahen's hypotheses without further research.

This considered, the time is now ripe to reassess the debate on the origins of the Germiyanids. First, under the impetus of a new generation of scholars, our understanding of the political, social, and cultural history of Seljuk and post-Seljuk Anatolia has increased greatly.Footnote 13 Second, it is now easier for researchers to access the seminal sources on the late Seljuks and early Germiyanids, such as Ibn Bībī's complete history of the Seljuks, known as Al-Awāmir al-ʿAlā’iyya, fi al-Umūr al-ʿAlā'iyya, published for the first time in 2011 by Jaleh Mottahedin.Footnote 14 Previously, with the exception of a few specialists, most historians had relied on the Mukhtaṣar, a useful, more readable, but occasionally hasty abridgement of the original text.Footnote 15 Regarding the early history of the Germiyanids, Ibn Bībī's Al-Awāmir contains precious fragments absent from the Mukhtaṣar and worth analysing. Likewise, the work of epigraphers and numismatists such as Ludvik Kalus and Steven Album has made access to inscriptions and coinage issued by the Germiyanids easier than ever.Footnote 16

Hence, as suggested in these introductory paragraphs, this article aims to use the latest scholarly and editorial developments to reassess Cahen's 1951 theories on the origins of the Germiyanids by drawing on a broad array of Islamic, Byzantine, Armenian, and Syriac sources. More specifically, this paper will focus on three key and much-debated claims made by Cahen. First, Cahen argued that the name “Germiyan” was that of a region, later given to a group and not, as was customary with the other beyliks, that of an eponymous founder. As for the etymology of “Germiyan”, Cahen tentatively suggested a possible connection between Germiyan and “Garm/Germ”, an Iranian root for “warm”, but did not further develop his thought. The first aim of this article is to find a more precise etymology and range of meanings for the word “Germiyan”. Second, Cahen suggested that “Germiyan”, the homeland of the dynasty, was a region in high Mesopotamia, north-east of Malatya. In this regard, the Notes are rather vague and do not clearly place Germiyan on a map of twelfth–thirteenth-century Anatolia. As such, this paper aims to delineate with a higher level of precision the boundaries of the Mesopotamian region known in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as “Germiyan”. Third, this article aims to re-assess Cahen's most (in)famous theory and find out the plausibility of: 1) the Germiyanids counting Kurdish tribesmen among their ranks; and 2) the presence of proto-Yezidi/ʿAdawi warriors in the Germiyanid armies.

It will be argued that “Germiyan” was not, as often proposed, a name of Armenian, Greek, Persian, or Turkish origin, but a Kurdish one, perhaps coined at the time of Kurdish expansionism in Eastern Anatolia. Later, “Germiyan” became the name of an organization or a confederation of people who had originated from a region known as “Germiyan”. Likewise, this article will show that, long before the first appearance of the Germiyanids in contemporary sources, Germiyan was not a vaguely defined locality adjacent to Malatya but rather a geographically defined region encompassing the valleys situated between Malatya and Lake Van extending along the eastern banks of the Euphrates River. Finally, it will contend that, even though contemporary sources are too vague to assess the proportion of Kurds and Turkmens among the Germiyanids, available evidence shows that at the time of the late Seljuks of Rum, the Eastern Anatolian region of Germiyan was inhabited by sizeable groups of Arab, Turkmen, and Kurdish pastoral nomads among which intense religious activity led by some of the most prominent figures of the early Yezidi movement took place.

1. Of what was Germiyan the name?

In the 1280s, whilst writing his magnum opus, a history of the Seljuk dynasty from the reign of Qilij Arslān II (d. 1192) onward, the Anatolian historian Ibn Bībī gazed upon the past to reminisce about a seminal event that took place during his youth. Whilst describing the infamous 1239/40 Bābāʾī revolt, a major anti-Seljuk uprising of Turkmen and Kurdish pastoralists, Ibn Bībī relates the deeds of Muẓaffar al-Dīn son of (pusar-i) ʿAlīshīr, an otherwise unknown Seljuk commander (sarlashkar) from Malatya. In a eulogistic but equally elegiac tone, Ibn Bībī sets the stage for the story of the first “son of ʿAlīshīr” to be encountered in historical sources. Muẓaffar al-Dīn is thus established as the leader of an army consisting of contingents of Kurds and Germiyan warriors (Kurdān wa Germiyān) who, invigorated by an intense sense of duty, defend their Seljuk lords to the peril of their lives.Footnote 17 This first historical reference to a group of people named “Germiyan” is deceptively straightforward. Notably, by juxtaposing it with the name of a clearly identifiable people, the Kurds, Ibn Bībī seems to indicate that “Germiyan” too was the name of a people. Likewise, such a clear-cut separation between Kurds and Germiyans hints at the latter being the name of a people of non-Kurdish origin.

Had the equation been this simple, the mysteries surrounding the meaning of “Germiyan” may not have puzzled historians for so long. As noted by the editors and translators of Al-Awāmir and of the Mukhtaṣar, neither Ibn Bībī nor the abbreviator of his work are very consistent with the use of “Germiyan”.Footnote 18 Thus, whilst describing later events, Ibn Bībī departs from the simple Kurd/Germiyan dichotomy and alternatively introduces the Germiyan people as “Turks of Germiyan” (atrāk-i Germiyān).Footnote 19 “Turks of Germiyan” is most commonly used in Ibn Bībī's history, but is occasionally nuanced by references to “Turks and Germiyan” (atrāk wa Germiyān)Footnote 20 but also “Turks and Kurds of/from Germiyan” (akrād wa atrāk-i Germiyāni).Footnote 21 Hence, the first historical reference to the Germiyan implies that the group had no connection to the Kurds of Malatya and the second alludes to Germiyan being the name of a Turkic people. Yet the third reference suggests Germiyan was the name of a non-Turkic people, and the last, the name of a group composed of Turks and Kurds.

In later chapters, the plot thickens further when Ibn Bībī brings the “sons of ʿAlīshīr” (awlād-i ʿAlīshīr) to the forefront of his narrative. In this case, around 1277, the “sons of ʿAlīshīr” are, once again, the leaders of a group of “Turks of Germiyan”, but this time settled somewhere between Afyonkarahisar and Sivrihisar, 730 kilometres west of Malatya as the crow flies.Footnote 22 From 1277 onwards, the Western Anatolian Germiyans, led by the “sons of ʿAlīshīr”, conquered various Byzantine and Seljuk fortresses in Western Asia Minor. By the early 1300s the “ʿAlīshīr Germiyans” had established a powerful emirate or beylik with its capital at Kütahya. In contemporary sources this beylik is typically referred to as “Germiyan”, in a similar fashion to the groups encountered near Malatya in the 1230s.

This remark would be of limited interest were it not for the naming conventions used by contemporary historians to designate the beyliks. Customarily, in Seljuk, Mamluk, and later Ottoman sources, the ruling dynasty of a beylik was referred to as “sons of” followed by the founder's name. To describe their followers, Turkmen or otherwise, contemporary witnesses used “Turks of” followed by the name of the dynasty's founder. Hence, the Ottomans or the Karamanids, to name only the most famous, are usually referred to in Persian, Turkish, or Arabic as “sons of Osman/Karaman” (Arabic: Ibn ʿUthmān/Qaramān; Persian: awlād-i ʿUthmān/Qarāmān; Ottoman: Osmanoğlu/Karamanoğlu) and their warriors as “Turks of Osman/Karaman”.Footnote 23 Occasionally, contemporary witnesses used sāhib (lord, owner), followed by the name of the most important city under their control (sāhib Bursā/sāhib Ermenāk, etc).Footnote 24

By these standards one would thus expect the Germiyanid dynasty to be referred to as “sons of ʿAlīshīr” (awlād-i ʿAlīshīr/abnā'-yi ʿAlīshīr), or “lord(s) of Kütahya” (sāhib Kūtāhīeh) and their followers as “Turks of ʿAlīshīr” (atrāk-i ʿAlīshīr). Yet, even though the ruling dynasty is invariably described as “sons of ʿAlīshīr”, its followers are always dubbed “Germiyan(s)”. When mentioned in sources from the Seljuk period and beyond, the “sons of ʿAlīshīr”, unlike the “sons of Osman” or the “sons of Karaman”, appear as entities connected to, yet distinct from, the group called “Germiyan” and from their warriors, the “Turks of Germiyan”. For instance, when describing the western and central Anatolian beyliks, the historian of the Seljuks Aqsarāyī establishes the “Germiyans”, the “emirs of Germiyan”, and the “sons of ʿAlīshīr”, as three distinct but connected groups hailing from Kütahya (umarāʻ-yi Germiyān wa abnā'-yi ʿAlīshīr āz Kūtāhīeh).Footnote 25 Following the naming conventions applied, the other beyliks one may have expected instead to find here would be something more akin to “the emirs of the sons of ʿAlīshīr” (umarāʻ-yi abnā'-yi ʿAlīshīr). On a few occasions, contemporary authors add the nisba Germiyāni next to “son(s) of ʿAlīshīr” (e.g. Ḥusām al-Dīn walad-i ʿAlīshīr-i Germiyāni), which makes it clear that the sons of ʿAlīshīr did not just lead but belonged to the group named “Germiyan”.Footnote 26

The dichotomy between “Germiyan(s)” and “sons of ʿAlīshīr” is equally acute in the work of Byzantine historians such as George Pachymeres and Nikephoros Gregoras. Pachymeres and Gregoras, two of the most important Byzantine scholars of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries witnessed, from the 1280s onward, the rise and growth of the Germiyanid beylik on the Seljuk/Byzantine frontier. Despite the cultural, religious, and geographic distance separating them from Ibn Bībī and Aqsarāyī, the two Byzantine scholars do not hesitate to single out (the) ʿAlīshīr (Ἁλισύρας/Ἁλισύραι) from the Germiyan(s) (Καρμανός/Καρμανοῖς).Footnote 27 Hence, whereas Osman (Ἀτμᾶνɛς) or Menteshe's (Μανταχίαι) Turkmens appear only under the name of the dynasty's eponymous founders, the Germiyanids are alternatively referred to as “Germiyanids” (Καρμανοῖς), “ʿAlīshīrids” (Ἁλισύραι) or as “ʿAlīshīr with (the) Germiyans” (Ἁλισύρας σὺν Καρμανοῖς).Footnote 28

At this point, and despite such a broad variety of testimonies, the exact origins and meaning of “Germiyan” remain rather unclear. A few interim conclusions can, however, be drawn. First, the use of the nisba Germiyāni to designate various groups of nomadic warriors, but also the sons of ʿAlīshīr, suggests that “Germiyan” must originally have been the name of a place from which the two had originated, or that of a tribe. Considering Ibn Bībī's account, this region or tribe must have been located near Malatya in Eastern Anatolia. Second, as indicated by the use of Καρμανοῖς in the work of Pachymeres and Gregoras, “Germiyan” was, at least by the fourteenth century, the name of an organization, a group of people, or perhaps a confederation settled near the Seljuk–Byzantine border and ruled by the sons of ʿAlīshīr. Third, the name and, by extension, the entity known as “Germiyan” was distinct from and must have predated the rise of the ʿAlīshīrids to power. Otherwise the whole organization would have been known not as “Germiyan”, but as “sons of ʿAlīshīr”, in similar fashion to their Ottoman, Karamanid, or Mentesheid neighbours.

This discussion, albeit crucial to understanding the meaning and scope of the name “Germiyan”, suffers from one glaring problem. Namely, the above analysis reflects the perception of external observers and not that of the group called Germiyan or the ʿAlīshīrid dynasty themselves. Unfortunately, unlike the Ottomans, the Karamanids, and the Aydinids, the Germiyanids did not leave histories extolling the prestige, organization, self-perception, and self-fashioning of their beylik and its ruling dynasty to posterity. There are, however, a few pieces of evidence delineating how the Germiyanids and their rulers perceived and fashioned themselves. Notably, three inscriptions found in Germiyanid territory are worth analysing. The first dates from 1299/1300. Originally engraved on the minbar of the Kızıl Bey Mosque of Ankara, the inscription extols the credentials of the Germiyanid commander YāqubFootnote 29 as a “great emir” (al-amīr al-kabīr) and a “son of ʿAlīshīr/ʿAlīshīrid” (ibn ʿAlīshīr).Footnote 30 A second, dating from 1324/25 and found on the walls of the citadel of Sandıklı once again introduces Yāqub as a great emir, but subsumes a second title, that of sulṭān al-Germīyānīya which may be roughly translated to “sultan of those [i.e. the people of] from/of Germiyan”. The combination between “the great emir” and “sultan of those from Germiyan” remained in use throughout the fourteenth century as evidenced on a third inscription dating from 1377/78.Footnote 31

Sulṭān al-Germīyānīya is an obscure title found, to my knowledge, only on these two inscriptions. It is interesting to note, however, that the sequence of titles establishes the sons of ʿAlīshīr as first and foremost “great emirs”, subordinates to the Ilkhanid Mongols, and second as sultans, in this case understood as “rulers”, not of a territory, but of an organization, or a group of people, the Germīyānīya. These inscriptions bring some additional nuance and reinforce our previous conclusions independently from the point of view of external observers. Notably, the use of Germīyānīya does confirm that the name “Germiyan” was either the name of a place or that of a tribal group. Likewise, this further confirms that unlike the Ottomans or Karamanids, whose followers were known as “sons of Osman/Karaman”, the sons of ʿAlīshīr may not have been the founders of the Germīyānīya but merely its leaders.

A twelfth-century source, the Chronicle of the Armenian historian Matthew of Edessa, suggests that “Germiyan” was indeed the name of a region. In his Chronicle, Matthew of Edessa conspicuously locates Germiyan near Malatya, in the exact region where Ibn Bībī first mentions the Germiyans and the sons of ʿAlīshīr.Footnote 32 Two nineteenth-century French orientalists, Edouard Dulaurier and Charles Defrémery, first noticed these references to “Germiyan” before trying to propose an etymology for the word and more precisely locate the region. Dulaurier, who did not fail to notice the intriguing similarities between the name of the region and that of the beylik of Kütahya, surmised that “Germiyan” must originally have been the name of a powerful Eastern Anatolian Turkmen warlord. Unlike Dulaurier, Defrémery understood “Germiyan” as an Armenian corruption of “Χαρσιανόν”, the name of a defunct neighbouring Byzantine theme (Byzantine district division). New hypotheses emerged in the twentieth century when Köprülü and Togan interpreted “Germiyan” respectively as a faulty rendering of “Kerman”, a region in eastern Iran, or of “Khwārazm” (Khwarezm), a region in Central Asia. The two Turkish scholars thus argued that thirteenth-century Turkmen migrants may have named the region “Germiyan” in remembrance of their homelands in Kerman or Khwārazm. Finally, Cahen and Varlık, surmised that “Germiyan” may have been a name of Iranian origin, related to “Garm/Germ” an Iranian root meaning “warm”.Footnote 33

A recent article by Thurin discusses and rejects most of these theories. Thurin argues that “Germiyan” could not have been the name of a Turkmen warlord since a commander mighty enough to give his name to a whole region would have been noticed by twelfth- and thirteenth-century historians such as Ibn al-Athīr or Bar Hebraeus. Likewise, the reading of “Germiyan” as a garbled Armenian rendering of Χαρσιανόν is difficult to maintain, as references to a region called “Germiyan” are also found in Georgian literature, a language radically different from Armenian. For similar reasons, Thurin argues that the connections between “Germiyan” and “Kerman” or “Khwārazm” are not sustainable since the name Germiyan can be found in local sources from long before the coming of Khwārazmian Turks to the region in around 1230. While it rejects these theories, Thurin's article does not discuss Cahen and Varlık's Iranian roots theory and simply concludes that “Germiyan” must have been the name given by locals to a region near Malatya.Footnote 34

Yet Cahen and Varlık's hypothesis deserves closer scrutiny. It is true that in both Classical and Modern Persian, the word “Garm” means “hot” and is used in many compound forms to denote warmth (e.g. garmā: “heat”; garm-khū: “hot tempered”, etc.). The word derives from the proto-Indo-European root *gʷʰer and relates to the English “warm” or the Greek “θɛρμός”.Footnote 35 However, as noted by Cahen and Varlık, the word “Germiyan” does not exist in Classical or Modern Persian. But the two scholars missed an important point: Persian was not the only Iranian language spoken in twelfth-century Eastern Anatolia. Long before Matthew of Edessa's birth, the Kurdish language had spread in the mountains and valleys of the region.

Bearing this in mind, a cursory glance at a variety of modern Kurmanji and Sorani dictionaries shows that “germiyan” is a rather common word with a closely related variety of meanings such as “hot place”, “lowlands”, or “winter pastures”. In other words, in modern Kurdish languages, “germiyan” is a close equivalent to “kışlak”, the better-known Turkic word for winter pastures.Footnote 36 Likewise, in the twenty-first century, Germiyan is the name of a Kurdish-majority region of Iraq surrounding the city of Sulaymaniyah, and known, as suggested by its name, for its hot weather. Finally, the nisba “Germiyani” (of/from Germiyan) is nowadays a very common surname among the Kurds of Iraq. Cahen and Varlık's oversight is easy to explain. Unlike Persian, Greek, or Armenian, which were prestigious literary and/or liturgical languages long before the twelfth century, Kurdish remained, until the seventeenth century, confined to the realms of oral history, religions, and traditions.

Thus, it seems safe at first glance to conclude that “Germiyan” was a name of Kurdish origin meaning “lowlands” or “winter pastures”. However, considering that no medieval Kurdish dictionary has survived, one may be tempted to oppose such a theory as anachronistic and perhaps baseless, since many of its foundations are grounded in modern etymology. Languages change over time, and “Germiyan” may have meant something different a thousand years ago. Yet, another element, this time grounded in medieval sources, gives additional credibility to the Kurdish connection. The work of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Muslim historians and geographers make abundant references to a region known as “Zūzan” or “Zūzan of the Kurds” (Zūzan al-Akrād), located in the mountainous regions south of Lake Van. In modern Kurmanji, “zūzan” (spelled zozan) is an antonym of “germiyan” and refers to “cold places”, “highlands”, and “summer pastures”.Footnote 37 To readers perhaps used to the Turkic vocabulary more often used by anthropologists of nomadism, the pair zūzan/germiyan is a Kurdish equivalent to the Turkic yayla/kışlak.

The origins, etymology, and meaning of the word “zūzan” have been discussed at length by Boris James. James, however, remains cautious and refuses to attribute “zūzan” its modern meaning. James therefore concludes that in the Middle Ages “zūzan” simply referred to a region in Eastern Anatolia inhabited not only by Kurds but also by a large Armenian community, rather than a generic word for summer pastures.Footnote 38 Despite James’ warranted cautious attitude, a broad variety of sources, dating from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries indicate that each summer, many of the Kurdish and Turkish pastoral nomads of Eastern Anatolia used Zūzan as their pasture. Hence, Ibn al-Athīr notes that, “in spring, […] the Turkomans, Kurds and Kilakan move from the places (al-ʾamkina) where they have wintered to Zūzan”.Footnote 39 A fifteenth-century Syriac history attributed to Ram'icho’ concurs with Ibn al-Athīr's testimony and claims that in the thirteenth century, the Tairahite Kurds spent their summers in Zūzan before migrating to Mosul at the end of the autumn.Footnote 40 Whereas the Syriac source highlights the migratory patterns of a specific Kurdish group, the Tairahites, Ibn al-Athīr uses a plural form (al-ʾamkina) to indicate that nomadic tribes moved to Zūzan not just from Mosul but from a broad variety of neighbouring regions used as winter pastures.

Based on these contemporary testimonies, it is safe to conclude that between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries, “zūzan” meant “highlands”, “cold place”, and “summer pasture”. If one is to accept that “zūzan” meant the same thing in the Middle Ages as it does today, then it is reasonable to treat “germiyan” with a similar standard. The present analysis is a case of Occam's razor. As such it is more likely for “Germiyan” to be a Kurdish word meaning “lowlands”, “warm place” or “winter pastures” than for it to derive from the (extremely) complex etymons proposed by Dulaurier, Köprülü, or Togan, such as Χαρσιανόν, or Khwārazm. Hence, one may confidently hypothesize that the pair germiyan/zūzan was used by the Kurdish and later Turkic pastoral populations of Eastern Anatolia as a naming convention for two broad areas used, respectively as winter and summer pastures. Conventions of such a kind were common in the past and still find echo in the twenty-first century, despite the decline of pastoral nomadism across Eurasia. We have mentioned the case of the Iraqi region of Germiyan, but in Turkey it is still common for the sedentary inhabitants of Mersin to call the nearby mountainous regions “yayla” or “summer pastures”.

This in no way contradicts the core of Boris James’ conclusions. Zūzan in the Middle Ages was the name of a region in Eastern Anatolia inhabited by a broad variety of ethnic, cultural, and religious groups, including Kurds, but also, as exemplified by Ibn al-Athīr's testimony, Turks and Armenians. Simply, the name of the region had derived from its status as the summer pastures of the Kurdish pastoral nomads of the region. With time and following the migration of a large group of pastoralists from Germiyan to Western Anatolia, “Germiyan”, or rather Germīyānīya, became the name of a confederation of people that had originally hailed from Germiyan, under the leadership of the “sons of ʿAlīshīr”. With this first interrogation clarified, let us turn to the second part of the inquiry: the precise location of Germiyan.

2. Where was Germiyan located?

Even though Matthew of Edessa states that Germiyan belonged to the territory of Malatya, the medieval historian never precisely sketched the boundaries, even approximate, of the region. Likewise, modern scholarship has seldom tried to solve the mystery. It is true that, at first sight, such a question may look trivial especially when compared to some of the salient issues raised in the present essay. However, this is a misleading thought. Throughout the Middle Ages, the early modern period, and until perhaps the exchange of populations that followed the aftermath of the First World War, Eastern Anatolia remained home to an extremely diverse array of cultures, ways of living, and religions. As such, without delineating the geographical boundaries of Germiyan, even with the limited level of accuracy inherent in such an exercise, it may remain difficult for scholars to understand fully the historical context behind the formation of the Germīyānīya but also the identity of the various groups that may have composed it.

As a first step, let us scrutinize the references to the region named “Germiyan” in Matthew of Edessa's History. Matthew's work is well known to twelfth-century historians and a full introduction is not necessary here.Footnote 41 Suffice to say that, as a native of Edessa and contemporary of the first and second crusades, Matthew witnessed first-hand the conflicts opposing the crusaders to the Muslim lords of the Near East. Germiyan appears for the first time in Matthew's work in the 1119 battle of ʿAzāz, which opposed Joscelin, the crusader Count of Edessa, to the Turkmen Lord Ilghāzī. Defeated by the crusader forces, Ilghāzī and his troops found refuge in Germiyan. Matthew concludes his chapter with a lesson in geography and locates Germiyan near Malatya and north of Ilghāzī's emirate.Footnote 42 Matthew's intentions when writing this chapter are worth analysing. Notably, Matthew's commentary shows that the location of Germiyan may not have been immediately obvious to his audience. Had the boundaries of Germiyan been clear to his potential readership, the Armenian historian would not have felt the need to state the obvious. One can hardly imagine Matthew having to locate Syria, Rum, or Iraq. As such, his explanations indicate that the name “Germiyan” may have been sufficiently unfamiliar to an educated twelfth-century reader to warrant additional explanations.

Matthew refers to Germiyan a second and final time in the following chapter, which deals with events taking place in 1121–22. In this section, Matthew relates the setbacks of Ghāzī, the emir of Ganja (modern Azerbaijan) who lost a major battle against the Kingdom of Georgia in 1122. In their quest for allies, the remnants of Ghāzī's armies took the road to Germiyan. There, they met Ilghāzī and begged the Turkmen lord to come to Ghāzī's help.Footnote 43 According to Matthew of Edessa, Ilghāzī responded to the call and summoned two sizeable Turkmen forces, one from Rum, the other from Germiyan.Footnote 44 The events of 1121–21 mark the last reference to Germiyan in Matthew's account, an absence perhaps explained by the relative decline in Artuqid power in the region after Ilghāzī's death in 1122.

Matthew's testimony, although crucial, is too vague and imprecise to sketch even a rough draft of a map. Nonetheless, one may, at this point, bring to the forefront a few interim conclusions. First, by virtue of its location, north of Ilghāzī's powerbases in Mayyafariqin and Diyarbakır, Germiyan must have been located somewhere near the northernmost territories under Artuqid control. Furthermore, keeping in mind that the Artuqids did not control Malatya and, considering that Ghāzī's forces looked for Ilghāzī in Germiyan, one must surmise that the region extended towards the north-east, beyond the immediate surroundings of Malatya. This considered, it is likely that Germiyan encompassed the region of Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād (modern Elazığ) and its vicinities. Finally, and despite the presence of fortresses and cities in Germiyan, Matthew's emphasis on the sizeable populations of nomadic Turkmen indicates that the region must have consisted of vast pasturelands, which further strengthens the idea that “Germiyan” meant “winter pastures”.

To clarify the boundaries of Germiyan, it is crucial to hunt down the few references to the region in contemporary sources other than Matthew of Edessa's history. The Kartlis Tskhovreba a compendium of chronicles on the history of medieval and early modern Georgia, usually known in English as Georgian Chronicles is one of such sources. To date, the Georgian Chronicles remain under-used, and sometimes underestimated by scholars of medieval Islam, mostly because of the incomplete nature of its most comprehensive translations. Nonetheless, the Chronicles contain important information on the people of the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia, in large part because of the extensive regional campaigns led by Georgia in the twelfth century. As in Matthew of Edessa's case, the Chronicles mention Germiyan on three occasions. The first report concerns a joint expedition between the Turkmens of Germiyan and those of Diyarbakır, against Georgia in 1160.Footnote 45 Later, the Turkmens of Germiyan returned to the forefront of history in 1185, when they joined an army from Erzurum, in a campaign against Queen Tamar.Footnote 46

The boundaries of Germiyan become more precise when comparing Matthew's History to the Georgian Chronicles. Notably, it is clear that Germiyan was not a sub-region of Diyarbakır or Erzurum, considering that the authors of the Chronicles separate the former from the latter. Consequently, whilst Malatya marked the westernmost border of Germiyan, Erzurum and Diyarbakır can respectively be established as the northernmost and southernmost borders of Germiyan.

Let us now return to Ibn Bībī's history, while keeping these conclusions in mind. Even though Ibn Bībī's history deals extensively with the early history of the Germiyanids, his work is devoid of geographic hints. However, Ibn Bībī's history, like the Georgian Chronicles, contains extensive and complementary information on the life of a man briefly connected to Germiyan, the exiled sultan of Khwārazm and Iran, Jalāl-al-Dīn Khwārazmshāh. Between 1225 and 1230, the buccaneering sultan and his troops intermittently clashed with both the armies of Georgia and the Seljuks of Rum. In 1230, the sultan fell prey to his ambitions when a joint Seljuk–Ayyubid army decisively routed his forces near Akhlat. Weakened and unable to withstand the advance of the Mongols, the Khwārazmshāh found refuge in the mountains north of Mayyafariqin. There, the ambitious king allegedly fell under the blade of a disgruntled Kurdish peasant. Whilst describing Jalāl-al-Dīn's fall, the Georgian Chronicles claims that, after the death of the Sultan, his forces fled to Germiyan.Footnote 47 Where exactly in Germiyan is never stated. The picture, however, becomes very clear when considering that, according to Ibn Bībī, after the death of Jalāl-al-Dīn, the Khwārazmian armies fled to Tatvan, on the western shore of Lake Van.Footnote 48

It is worth noting, first, that his troops fled from an outside region to Germiyan, and did not move within the boundaries of the region. This allows us to set the mountain range south of Tatvan and north of Mayyafariqin as the southern boundaries of Germiyan. It is also important to note that Tatvan stood a few kilometres from Akhlat, a place defined by Arab geographers as the northern frontier of Zūzan. The immediate proximity between the frontiers of Zūzan, the “summer pasture region”, and Germiyan or the “winter pasture region” is far too convenient and striking to be ignored.

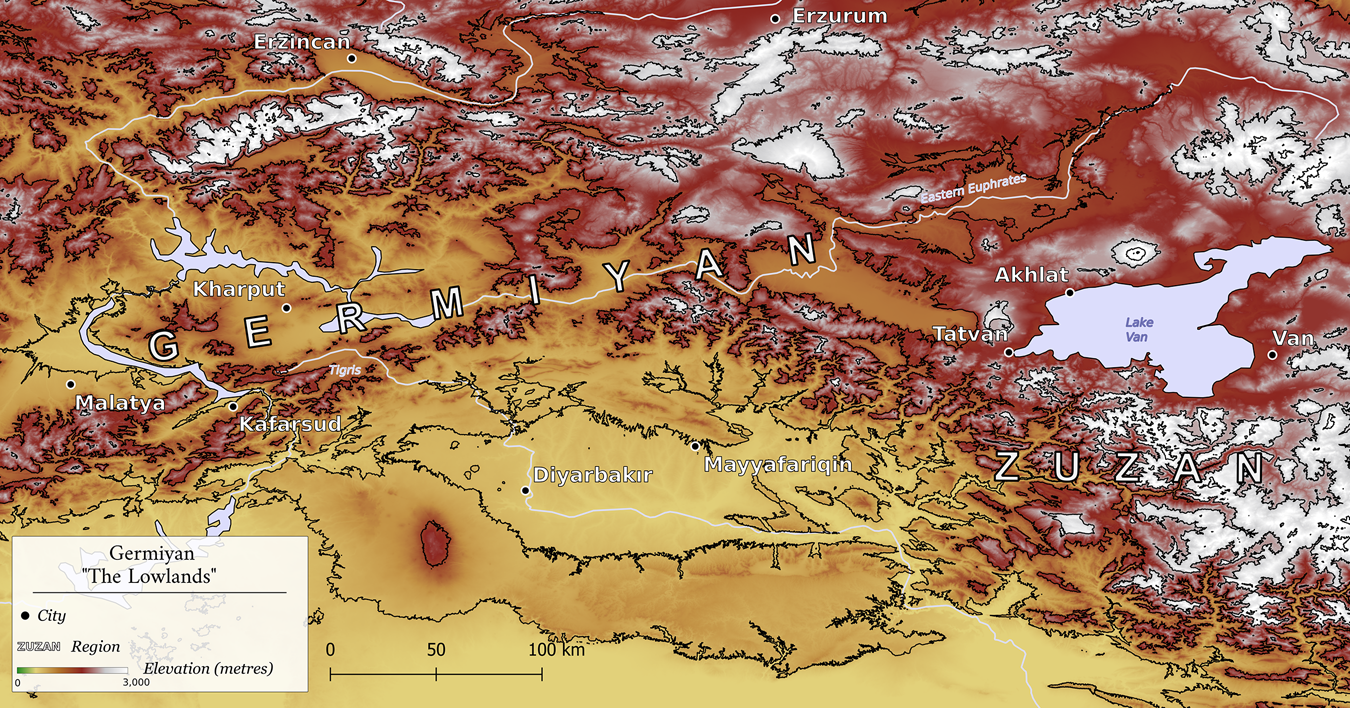

In short, Germiyan, the homeland of the latter Germīyānīya, was located between Malatya in the west, Erzurum in the north, the Anti Taurus Mountain range, north of Diyarbakır and Mayyafariqin in the south and Tatvan, Akhlat, and the Zūzan region in the East. When plotting these cities on a map and looking at the geography of the region, the drawing becomes more precise. The region going from Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād to Tatvan is a valley sandwiched between the Taurus and anti-Taurus ranges. Likewise, as noted by ecologists, the weather in these valleys is moderate and perfectly suited for winter pastures. Finally, and without equating the behaviour of medieval nomads to that of modern pastoralists, often constrained by the coercive powers of modern states and boundaries, it is worth noting that, in the twenty-first century many Eastern Anatolian Kurdish shepherds still use the regions surrounding Kharpūt as winter pastures (see Figure 1).Footnote 49

Figure 1. Map of Germiyan

3. Who lived in Germiyan?

To suggest that the Germīyānīya counted a sizeable proportion of Kurdish and potentially Yezidi warriors among its ranks, Cahen relied on a brief testimony left by Ibn Battuta. While travelling near Gölhisar in south-west Anatolia in around 1330, the North African voyager heard hearsay on the Germīyānīya and reports that: “A group of bandits named Germiyan cut the roads in this plain. It is said that they descend from Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya and control a city named Kütahya”.Footnote 50

Today, Yezidism is known as a syncretistic monotheistic religion that incorporates elements from both ancient Iranian religions and Islam. Most Yezidi are Kurmanji-speaking Kurds and live in northern Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and the Caucasus. At the time of Ibn Battuta's journey, the Yezidi religion had not yet taken its current form and was known as ʿAdawiyya, the name of a Sufi order, founded in the twelfth century by Sheikh ʿAdī ibn Musāfir (d. 1162), an alleged descendant of the Umayyad Caliph Marwān ibn al-Ḥakam (d. 685).Footnote 51 A fundamental aspect of the ʿAdawiyya movement was a belief in the imamate of the Umayyad caliph Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya (d. 683).Footnote 52 Contemporary Muslims viewed such a belief with great scepticism, as both Shia and Sunni Muslims reviled Yazīd for the murder of Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī and for turning the Caliphate into a hereditary monarchy. For instance, a contemporary of Ibn Battuta condemned the love expressed to Yazīd by the members of the ʿAdawiyya in these terms: “Those ignorant ones began to cherish and praise Yazīd without knowing his true nature. They go as far as to say […] ‘the blood and goods of those who do not love Yazīd are licit to us’.”Footnote 53

Taking this into consideration, Cahen found the association between the Germīyānīya and Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya too specific to be coincidental. He thus speculated that since Eastern Anatolia was home to large groups of Yezidi Kurds, it was plausible that either some of these people had followed the Germīyānīya to Western Anatolia, or that Yezidi beliefs had spread among the non-Kurdish people of the Germīyānīya.Footnote 54 Varlık, later dismissed such an idea and interpreted “descendants of Yazīd” as an insult used by the people of Gölhisar to discredit the Germīyānīya as mere “rebels” (asi).Footnote 55

To give Varlık credit, it is true that Cahen did not substantiate his thoughts beyond making references to the existence of Kurdish and Yezidi settlements in Eastern Anatolia. Given the timeframe of Ibn Battuta's journey, the most appropriate approach to test both the reliability of such a testimony, and Cahen's subsequent conclusions, would involve examining early fourteenth-century sources that provide clues about the ethno-religious composition of the Germīyānīya. Unfortunately, the available sources are too limited to do so. The historian of the Seljuks, Aqsarāyī, briefly mentions the leaders of the Germiyanids, but does not delve into their ethno-cultural or religious make-up.Footnote 56 Likewise, the Byzantine scholars, Pachymeres and Gregoras are almost exclusively concerned with the loss of Byzantine fortresses to the Germiyanids and show little interest in their organization.Footnote 57 As for the Syrian polymath, al-ʿUmarī, the scope of his work remains limited to drawing very broad strokes, despite his evident interest in the history of the Germīyānīya and for the sons of ʿAlīshīr.Footnote 58 Hence, considering the limits of fourteenth-century sources, an alternative methodology consists in analysing population settlements in the Eastern Anatolian region defined in this article as “Germiyan” between the 1230s and 1277, which is when the Germīyānīya is first mentioned near the Seljuk–Byzantine frontier. However, this approach is beset with difficulties, once again, largely because of a limited breadth of sources. Nonetheless, a few geographic and ethnographic reports have survived, and their analysis may yield better results than working with the almost non-existent fourteenth-century sources.

Before the Seljuks, Eastern Anatolia had been, through the centuries, the end point of several waves of Arab and Kurdish migrations and had become home to large groups of Arab and Kurdish pastoralists. Providing a detailed account of these migrations is beyond the scope of this discussion. Suffice it to say that during the heydays of the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, various Arab tribesmen and sedentary mujahideen settled in the regions surrounding Malatya to safeguard the Caliphate's frontiers against a resurgent Byzantine Empire.Footnote 59

To date, the precise timing of the arrival of the Kurds in the region remains a matter of debate. More important is the fact that, amidst the collapse of the Abbasid Caliphate in the tenth century, Eastern Anatolia witnessed the emergence of powerful regional dynasties of Kurdish origin such as the Marwanids. It may be under the Marwanids that the local Kurds coined the terms “Germiyan” and “Zūzan” for the first time, if not as an official administrative division, perhaps as an ad hoc denomination highlighting the realities of pastoral nomadism in the region.Footnote 60

A third group, the Turkmens, migrated to Eastern Anatolia around the time of the Byzantine defeat of Manzikert (1071) against the Great Seljuks. During that period, a relatively unknown emir named Çubuk and his Turkmen warriors, established a short-lived emirate in the vicinity of Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād. Throughout the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the Turkmens of Germiyan formed a loosely organized group, perhaps a confederation. Nothing precise is known about their organization in the twelfth century, except that they pledged allegiance to the Artuqids, perhaps out of respect for the prestige of their alleged Döğer-Oghuz origins.Footnote 61

It is well established that during the Seljuk period, the sudden influx of Turkmens to Eastern Anatolia did not force the Arab and Kurdish populations out of the region. Matthew of Edessa, Ibn al-Athīr, and Bar Hebraeus, who wrote in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries show, on various occasions, that the three groups cohabitated in Germiyan. However, the nature of their interactions in the twelfth century remains unclear and subject to speculation. Based on comparisons with the better-known neighbouring region of Zūzan, it is likely that their relationship fluctuated between conflict and cooperation, with occasional intermarriages and merging of tribes.Footnote 62

Whilst limited information exists regarding the Arabs and Turkmens who dwelled in Eastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia, the surviving sources provide more extensive details concerning the “peculiar” beliefs held by certain groups of Kurds residing in these areas. Notably, the twelfth-century historian al-Sam‘ānī mentions the existence of Kurdish communities in the mountainous regions north of Mosul who worshipped Yazīd decades prior to the formation of the ʿAdawiyya order.Footnote 63 Many of the Kurdish tribes and confederations of the region not only revered Yazīd, but also claimed Umayyad ancestries. Al-ʿUmarī, among others, dedicates a subsection of his Masālik al-Abṣār to the Jūlmarkīya, a Kurdish confederation that claimed to be Kurdified descendants of the Umayyad Caliph Marwān b. al-Ḥakam.Footnote 64 These claims persisted over time. In the fifteenth century, the pseudo-Ram'icho’ branded the Yezidis as worshippers and descendants of Yazīd.Footnote 65 Similarly, the sixteenth-century Kurdish historian Sharaf al-Dīn Bidlīsī, a prominent expert in Kurdish history, calls Yezidi people “relatives” (mansūb) of the Marwanid Umayyad caliphs.Footnote 66 In the seventeenth century, Ottoman historians continued to describe the Yezidi as “descendants of Yazīd”.Footnote 67

Evident throughout these testimonies is a discernible pattern: from the twelfth century, and quite possibly even earlier, the Kurdish inhabited regions of Eastern Anatolia and Upper Mesopotamia were steeped in a philo-Umayyad climate. Within this milieu, numerous Kurdish tribes held steadfast beliefs in the sanctity of Yazīd and in their Umayyad ancestries. Such convictions are highly specific, and too intimately connected to the Kurdish communities of Eastern Anatolia to follow Varlık's lead and dismiss Ibn Battuta's claims as an odd and elaborate slur. To what extent these philo-Umayyad and philo-Yazīd Kurdish groups may have been connected to the Germīyānīya will now be explained.

In the second third of the thirteenth century, regional conflicts and, later, the coming of the Mongols, brought important socio-political changes to Eastern Anatolia. In this chaotic era, the war-torn regions surrounding Malatya witnessed an intensification in the formation and activities of mixed Kurdish/Turkmen war bands led by charismatic local leaders. In the city of Kafarsud (modern Doğanyol/Keferdîz), a messianic preacher named Bābā Ishāk, capitalized on the discontent of the local Kurdish and Turkmen pastoralists to incite a revolt against the Seljuks.Footnote 68 By 1238, Bābā Ishāk's Kurdish/Turkmen insurgent forces fought against, and were eventually defeated by, the Seljuks, whose struggles against the rebels convinced the Mongols to launch the invasion of Anatolia.Footnote 69 Equally important is the fact that, on the roads between Kafarsud and Malatya, Baba Ishāk and his anti-Seljuk Kurdish/Turkmen force fought against the pro-Seljuk Kurdish/Turkmen armies led by the Germiyanid leader Muẓaffar al-Dīn ibn ʿAlīshīr.Footnote 70

The formation of mixed Kurdish/Turkmen war bands further intensified after the Mongol invasions (1243). In 1243, an alliance comprising Turkmens and Kurds from Germiyan, along with a nomadic force from Ganja, launched a series of raids against a group of refugees fleeing the Mongol advance in south-east Anatolia.Footnote 71 The leaders of these bands of Germiyans remain unknown. However, it is unlikely that ʿAlīshīr and his sons, who fought loyally for the Seljuks in the 1230s and later in the 1250s, turned against their masters’ subjects in the 1240s. It is safer here to assume that the process which eventually led to the formation of the western Anatolian Germīyānīya, led by the sons of ʿAlīshīr, had not yet taken place. In other words, many of the Kurdish/Turkmen war bands labelled “Germiyan” in the 1230s/1240s likely operated independently, separate from the influence of the ʿAlīshīrids.

The troubles of 1243 mark the last reference to the Turkmens and Kurds of Germiyan in contemporary sources until the Karamanid revolt of 1276/78 which saw the Germīyānīya fight against the anti-Mongol insurgent force led by Meḥmed Bey ibn Karaman in central and western Anatolia. Surprisingly, the abrupt appearance of the Germīyānīya in western Anatolia has garnered significant scholarly attention. According to the prevailing consensus, the people who later formed the Germīyānīya relocated from Eastern Anatolia to the Seljuk–Byzantine border zone between 1261 and 1265.Footnote 72 It is unnecessary to delve into this argument here, and for now, the dates proposed by various historians should be retained. However, what transpired among the pastoral nomads of Germiyan and the ʿAlīshīrid family between 1243 and 1261–65 remains entirely unexplained.

Despite the absence of direct references to the Germīyānīya, or the ʿAlīshīrids, between 1243 and 1277, the region identified as “Germiyan” in this article remained the epicentre of significant political, social, and religious developments between 1243 and the 1260s. In the 1250s and early 1260s, the power struggle between the two Seljuk princes Kaykāwus II and Qilij Arslān IV drew the people of Germiyan into the whirlwind of civil war. In the first half of the 1250s, Kaykāwus had the upper hand over his rival, and eventually placed him under house arrest around 1254. Key to Kaykāwus’ triumph was the support of several Turkmen, Kurdish, and Arab nomadic groups from the Gülnar, Bulgar, and Bozkir regions of south-central Anatolia.Footnote 73

However, Kaykāwus’ fate took a turn for the worse in 1256 when the Mongol commander Baiju Noyan, at the behest of Hulagu Khan moved his troops to central Anatolia. Hulagu's decision set the Mongols on a collision course with Kaykāwus as the sultan adamantly fought to preserve his autonomy in the face of the conquering forces. In 1256, near Aksaray, Baiju ruthlessly crushed Kaykāwus’ nomadic forces. Following the defeat, Kaykāwus abandoned Konya and sought refuge in the temporary Byzantine capital of Nicaea whilst Baiju dismantled the remnants of the sultan's army. A year later, following successful negotiations with Hulagu Khan, Kaykāwus returned to Anatolia and reclaimed his position, this time as co-sultan alongside Qilij Arslān, but without the support of his once powerful army.Footnote 74 Concerned about the ambitions of both his brother and Baiju, Kaykāwus sought to rebuild his forces. The frightened sultan turned his attention towards Eastern Anatolia and engaged negotiations with the nomadic communities living around Malatya and Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād.Footnote 75 As before, Kaykāwus succeeded in raising multiple hosts of nomads in these regions. As shown by Bar Hebraeus and the pseudo-Ram'icho’ the new army, like the old one, counted among its ranks a variety of Turkmen, Kurdish, but also Arab warriors.Footnote 76

Equally important to the current analysis are the names and origins of the two individuals appointed by Kaykāwus to lead his new army. The first and less significant of the two was Sharaf al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn Bilās, an Eastern Anatolian Hakkari Kurdish lord. In exchange for his support, Aḥmad received Malatya as a land grant (iqṭāʿ). The second individual, Sharaf al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan (Kurmanji Kurdish: Şêx Şerfedîn), also a Kurd, received the fortress of Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād.Footnote 77 To date, the stature and significance of Sharaf al-Dīn Muḥammad's presence among Kaykāwus’ armies has been overlooked by scholars of Medieval Anatolia.

Far from being an unremarkable regional Kurdish leader, Sharaf al-Dīn Muḥammad was the son of al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAdī (Kurmanji Kurdish: Şêx Hesen), a highly renowned sufi master.Footnote 78 Today, al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAdī is known as one of the founding figures of the Yezidi faith. During the thirteenth century, when Yezidism had not yet taken its modern form, Al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAdī held authority over the ʿAdawiyya sufi order, established in the twelfth century by his great uncle, Sheikh ʿAdī ibn Musāfir. At the time, Al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAdī's followers were already known for their occasionally excessive – at least from a Muslim perspective – veneration of the figure of Yazīd b. Muʿāwiya, and sporadic claims of Umayyad ancestry.Footnote 79

Before 1254, Sheikh Ḥasan had dedicated much of his life to spreading the ʿAdawi creed in Mesopotamia, particularly in the city of Mosul which was at the time ruled by the Zengid Atabeg Badr al-Dīn Luʾluʾ. During Sheikh Ḥasan's tenure, the influence of the ʿAdawiyya grew exponentially among the Kurdish communities of Mosul and northern Mesopotamia. There, his followers became known as “ʿAdawi Kurds” (Akrād ʿAdawiyya). However, the growing popularity and influence of the order drew the ire of Badr al-Dīn Luʾluʾ. In 1254, concerned with the increasing fame and authority of Sheikh Ḥasan, Badr al-Dīn Luʾluʾ arrested the leader of the ʿAdawiyya and ordered the massacre of hundreds of ʿAdawi Kurds along with the desecration of Sheikh ʿAdī's remains.

Despite his father's demise, Sharaf al-Dīn managed to survive the ordeals faced by the order, eventually inheriting the leadership of the ʿAdawiyya tariqa, and making his way to Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād.Footnote 80 As noted by scholars such as John S. Guest, the available sources do not provide a clear account of whether Sharaf al-Dīn escaped Mosul unharmed during the purges, or had already established himself in Kharpūt/Ḥiṣn Ziyād prior to the massacres. Moreover, the reasons behind his presence in Eastern Anatolia remain unclear.Footnote 81 Given the scarcity of evidence, it is tempting to speculate cautiously that Sharaf al-Dīn might have been sent by his father to preach among the local nomadic tribes in the years preceding the massacres or chose to settle in an area already aligned with his order's belief in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Regardless of the precise timing of Sharaf al-Dīn's relocation to Eastern Anatolia, his appointment as the leader of Kaykāwus’ armies was hardly coincidental. Leadership among the nomads of Medieval Eurasia has been extensively studied by modern anthropologists and historians. Contemporary sources offer numerous examples showing that medieval nomads placed great importance on military prowess, prestigious lineage and/or religious charisma when appointing a leader.Footnote 82 Conspicuously, Sharaf al-Dīn was not a battle-hardened veteran of many wars, but the leader of a religious order. As a shrewd ruler experienced in negotiating with and commanding nomadic armies, Kaykāwus must have recognized the importance of choosing a charismatic and respected local figure to command and impose authority upon a large force of pastoral nomads.

Kaykāwus’ judgement proved adequate as demonstrated by the sheikh's ability to raise promptly a subsequent force of local Kurdish, Turkmen, and Arab nomads upon sealing his alliance with the sultan. These events not only highlight the magnitude of Sharaf al-Dīn's political authority within these regions but also suggest, considering the presence of Turkmen and Arab warriors alongside the Kurdish followers typically associated with his order, that the political influence and authority of the ʿAdawi master otherwise known as “Sheikh of the Kurds” (Sheikh al-Akrād) had reached a wide-ranging and diverse audience in the years preceding his alliance with Kaykāwus.Footnote 83 Given Sharaf al-Dīn's ability to garner political and military allegiance from such a broad spectrum of warriors, one can plausibly infer that the principles and teachings of the ʿAdawiyya tariqa might have also gained popularity among the non-Kurdish people of the region.

The role played by the ʿAlīshīrids in these events remains uncertain. Nonetheless, based on scattered evidence, one could hypothesize that Karim al-Dīn ʿAlīshīr, the dynasty's patriarch, fought on Kaykāwus’ side against the Mongols. After 1261, when the Mongols expelled Kaykāwus from Anatolia once and for all, the new regime, led by his brother Qilij Arslān in alliance with the Mongols, tried several emirs and generals who had sided with his brother in the late 1250s. Among them was Karim al-Dīn ʿAlīshīr, whose fate along with that of Kaykāwus’ other supporters is lamented by Ibn Bībī.Footnote 84 Unfortunately, the exact reasons that led to ʿAlīshīr's execution, beyond his loyalty to the fallen sultan, are never clearly explained by Ibn Bībī. ʿAlīshīr's fate suggests that Qilij Arslān and the Mongols perceived the Germiyanid leader as a potential threat to their authority. It is thus likely, considering ʿAlīshīr's loyalty to Kaykāwus and the perceived threat, that during the 1250s the emir fought for the sultan at the head of a force of people from Germiyan, perhaps, albeit hypothetically, under the aegis of Sheikh Sharaf al-Dīn's grand army.

To summarize, the eastern Anatolian region defined in this article as “Germiyan”, already known in the twelfth century for being home to a significant variety of people of different ethnic, cultural, and religious backgrounds, witnessed, from the second third of the thirteenth century onward, a period that coincided with the formation of the Germīyānīya, a strong intermingling of Turkish, Kurdish, and occasionally Arab nomadic groups. Many of the Kurdish groups established in the region had long claimed to descend from the Umayyads, held beliefs in the sanctity of Yazīd and in some instances followed the teachings of philo-Yazīd/early Yezidi leaders such as the ʿAdawi sheikh al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAdi. In the second half of the thirteenth century, as exemplified by the career of Sharaf al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan, the political, military, and perhaps religious influence of ʿAdawi preachers spread further and reached an audience of Arab and Turkmen nomads far beyond the traditional core of Kurdish followers of the orders. Considering the proliferation of philo-Yazīd beliefs, the presence of ʿAdawi leaders in Eastern Anatolia, and the multiple military alliances between Turkmens and Kurds of Germiyan frequently mentioned in thirteenth-century sources, it is likely that the Germīyānīya, a confederation of nomads from the region of Germiyan, took a similar multi-ethnic and multi-confessional character.

This hardly means that the “Germiyans” encountered by Ibn Battuta in 1330 are representative of the entirety of the Germīyānīya. Yet considering the above-mentioned examples, it is equally challenging to dismiss the references to the Germiyans being descendants of Yazīd as an odd insult used to discredit the Germīyānīya. Here, a more balanced assessment would be to conclude that whilst crossing the plains separating Kütahya from Gölhisar, Ibn Battuta encountered a philo-Yazīd group of nomads from the Germīyānīya, perhaps of Kurdish origins, that had migrated to Western Anatolia around 1260.

Conclusion

This article's primary aim was to re-evaluate the most controversial hypotheses laid down over seventy years ago by Claude Cahen in his Notes pour l'histoire des Turcomans d'Asie Mineure. Much of Cahen's critique was to some extent valid. At the time, some of his theories looked more like hunches than substantiated evidence. Yet, under closer scrutiny, most of Cahen's theories and even hunches can be more firmly demonstrated. In his Notes, Cahen suggested that the word “Germiyan” may have derived from the Iranian root “Garm/Germ”. Following this lead, this paper showed that Germiyan indeed derived from an Iranian language – Kurdish – and meant something akin to “lowlands” or “winter pastures”. With time, and following the migration of a group of nomads from eastern to western Anatolia, “Germiyan” became the name of a group of people, the Germīyānīya, roughly translatable into “those from Germiyan” and led by a family known to posterity as the “sons of ʿAlīshīr”. Likewise, following a testimony left by Matthew of Edessa, Cahen once posited that Germiyan may have been located somewhere near Malatya. In response to such an early hypothesis, this article located “Germiyan” as a broad corridor of valleys between Lake Van and Kharput.

The last of Cahen's hypotheses reassessed here is his claim that sizeable groups of proto-Yezidi Kurdish warriors may have fought among the ranks of the Germīyānīya. On that front, and in keeping with the cautious nature inherent to scholarship on Medieval Anatolia, one can only safely conclude with a lukewarm “probably”. The spread of the ʿAdawi creed among the Kurds, and possibly among the Turkmens and Arabs of Germiyan in the decades preceding the migration of the Germīyānīya to western Anatolia, is best exemplified by the prevalent influence of sheikh Ḥasan in the region. As such, it is not implausible to conceive that Kurdish tribes and, among them, followers of the ʿAdawiyya tariqa were part of the Germīyānīya. This would not be in any way exceptional or unique to the Germīyānīya. In the thirteenth century, the Khwārazmīya, a predominantly Turkic nomadic confederation, counted among its warriors a sizeable force of Kurds. The same can be said of later nomadic organizations such as the Aq Qoyunlu or the Boz Ulus. As such it is plausible, if not probable, that ibn Battuta encountered ʿAdawi Kurds and/or philo-Yazīd Turks or perhaps even Arab nomads fighting for the Germīyānīya around 1330.

As a final note, it is tempting here to broaden these conclusions far beyond the case study of the Germīyānīya. Although more research needs to be done, the presence of powerful warriors/tribes of Kurdish and occasionally Arab origins in the retinues of the commanders who founded the Anatolian beyliks seems to have been commonplace. Contemporary witnesses such as Ibn Bibi frequently allude to the presence of Kurds in south-central Anatolia. Some of these tribes even fought for the Karamanids in 1276/78. Similarly, a much later history, the Karaman- nāme of Shikari, indicates that various Kurdish groups followed Karaman Bey in the early days of the dynasty.Footnote 85 Recently, Dimitri Korobeinikov proposed that the Mentesheid beylik may have been of mixed Turkish/Kurdish origins.Footnote 86 Unfortunately, the role and significance of Kurdish and Arab people in the formation of the beyliks has been overlooked. This may be a direct consequence of the unprecedented influence of the nationalist Turkish school of history in shaping the field. The time may now be ripe to re-examine the origins and early history of the so-called “Turkmen beyliks” in order to provide a more nuanced and accurate understanding of this field, which has often been oversimplified in the past.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Amy Constable and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.