No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

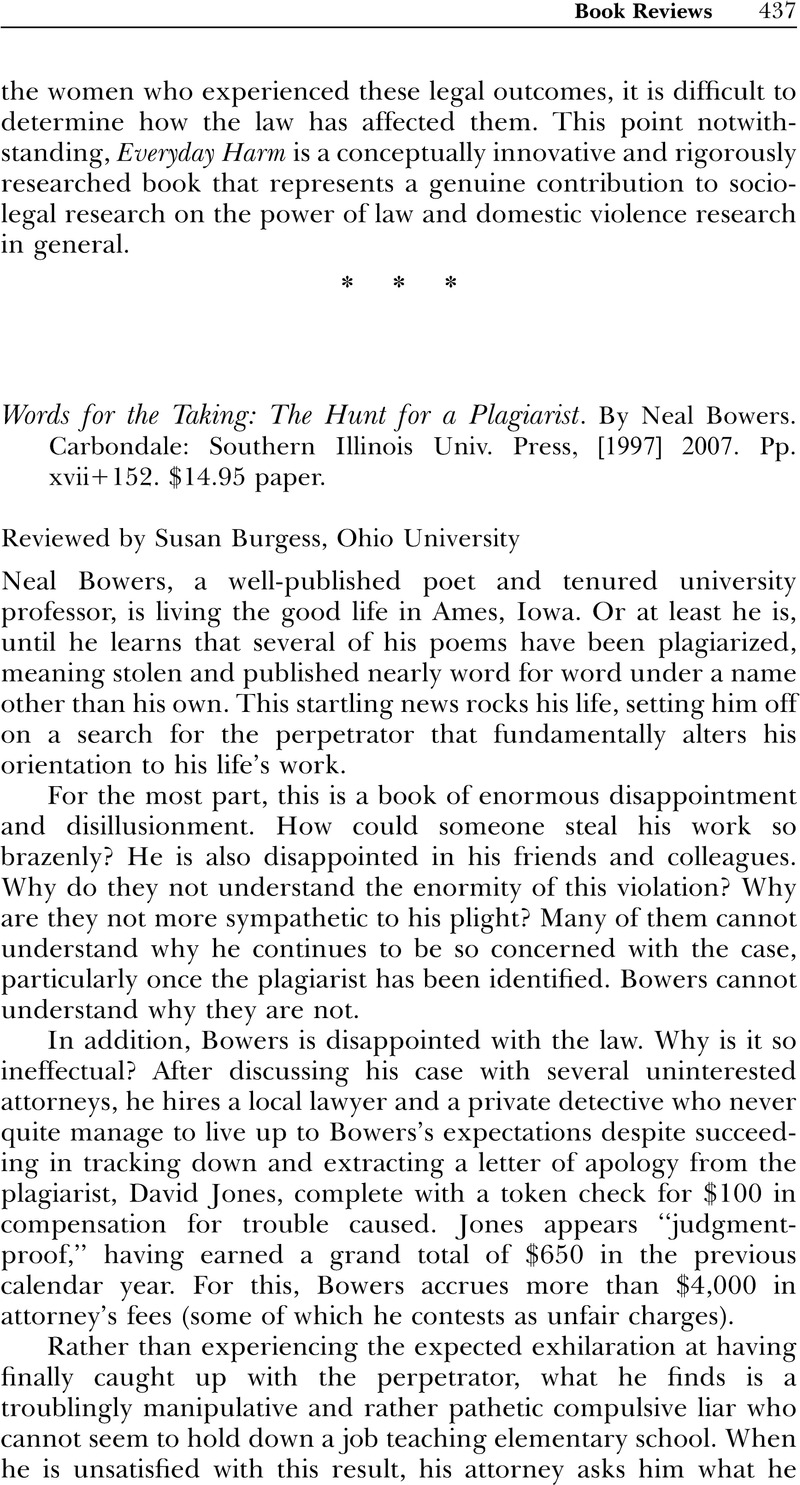

Words for the Taking: The Hunt for a Plagiarist. By Neal Bowers. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, [1997] 2007. Pp. xvii+152. $14.95 paper.

Review products

Words for the Taking: The Hunt for a Plagiarist. By Neal Bowers. Carbondale: Southern Illinois Univ. Press, [1997] 2007. Pp. xvii+152. $14.95 paper.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 January 2024

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Book Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2008 Law and Society Association.

References

The Cortland Review (1998). “Interview,” Neal Bowers, http://www.cortlandreview.com/issuefive/interview5.htm.Google Scholar