The panorama was from its outset a medium of contemporary history—a way for its audiences to access, experience, and evaluate recent historical events. This new form of artwork was invented as a 360-degree painting by Robert Barker in 1787, on the eve of the French Revolution, and then diversified into “moving” (scroll-based) forms with lectures and music. From the French Revolutionary Wars onward, panoramas regularly represented recent events, becoming a crucial part of the way that these were mediated to, reflected on, and debated by the nineteenth-century public. In a recent survey of the form, Laurie Garrison asks in a manifesto for future work: “What relationship did the panorama have to military history as it was being written in the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic and colonial wars of the nineteenth century?”Footnote 1 This article contributes to answering that question by investigating how panoramas and early histories represented the “Indian Mutiny” of 1857–59.Footnote 2

One of the challenges of depicting historical events in their immediate aftermath—as panoramas did—is lack of temporal distance. This concept has been valuably interrogated in recent years by Mary Favret and Mark Salber Phillips. In War at a Distance (2009), Favret argues that spatial and geographical distance can function as a substitute for temporal distance, replacing the hindsight that historians normally feel is required in order to narrate the recent past.Footnote 3 Salber Phillips highlights that chronological proximity often generates antagonism to the designated enemy of warfare, whereas chronological distance can enable openness to greater affective proximity.Footnote 4 He suggests, as does Susan Sontag in her revised discussion of images of warfare (2004), that it is easier to be compassionate with distance.Footnote 5

Panoramas, which depicted recent warfare in detailed and sometimes graphic visual form, were persistently accused of voyeurism.Footnote 6 The “Indian Mutiny” acted as something of a lightning rod for this critique. Graphic representations of violence might be driven by a determination to confront difficult experiences. When we use the voyeurism label, however, we imply that the representation is not in fact necessary, but merely gratuitous. This article examines to what extent panoramas’ depictions of Indian Uprising violence should be seen as voyeuristic in their representation or reception, and to what extent they invoked patriotic and militaristic jingoism in the service of empire.

The “Indian Mutiny” began being represented in newspapers and pamphlets while its events were still going on. It was then heavily represented in circular and moving panoramas, other forms of show culture such as dioramas, in the theater itself in sensation plays, in short stories and novels, and in several histories published over the following decades. Initial British responses to the uprising therefore brought together several different kinds of distance. It was chronologically very close but geographically very distant from readers and audiences in the British Isles. This geographical distance perhaps substituted for the lack of temporal distance in enabling narrative. However, while other recent colonial encounters (such as the Afghan Wars of the 1840s) took place on the borders of the empire and chiefly concerned sections of the British army, the Indian Mutiny diverged from those encounters in three significant ways. It struck at the heart of the empire; it was arguably the fault of British policies; and it led to massacres of British civilians, including women and children. It was therefore extremely highly charged in emotional and political terms—or, to put it another way, it felt very close.

Much British material on the uprising reads to us as jingoistic. Much scholarly work has been done on the most vitriolic material, such as Dickens's geographically transposed play jointly written with Wilkie Collins, The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857). Patrick Brantlinger has described the way that Victorian writers wrote about the Indian Uprising as one that “bar[red] the door against imaginative sympathy.”Footnote 7 A range of scholars—including Jenny Sharpe, Nancy Paxton, Gautam Chakravarty, Astrid Erll, and Christopher Herbert—have built on Brantlinger's lead and showcased the lurid, vituperative, and chauvinistic material that built up around the mutiny, especially in fiction. Salber Phillips's framework might suggest that responses to the uprising would become less jingoistic as it became more chronologically distant. On the other hand, a memory studies perspective might suggest the opposite, as initial “communicative memory” gives way to monolithic “Cultural Memory.”Footnote 8 In that framework, Astrid Erll has argued that mythmaking turned the uprising into a “monolithic” cultural memory for the British Empire that allowed “no room for divergent versions or even counter-memory.”Footnote 9

This article therefore asks: Was there room for debate and nuance within the panoramas and historical writings produced in the first two decades after the Indian Uprising? We have become accustomed to thinking of imperial experience of the late nineteenth century onward as highly conflicted, as expressed in the writings of Kipling, Conrad, and others.Footnote 10 Recent scholarship brings this timeline backward to the Indian Uprising, which—by bringing the South Asian colonies under direct Crown control—arguably instigated that phase of British imperialism. Herbert has argued that far from being hegemonically self-satisfied, British responses to the uprising demonstrate “deep, anguish-laden cracks [. . .] in the Victorian mentality.”Footnote 11 Building on this analysis but going beyond the single notion of anguish with its emphasis on affect, I show that Victorian representations of the “Indian Mutiny” were not governed solely by one monolithic myth. The range of contemporaneous response to the mutiny was more nuanced than its most famous examples suggest.

Part 1 briefly examines the kinds of historical narratives that panoramas could produce, inquiring to what extent panorama painters and their audiences could be subversive in how they did so. Part 2 turns to compare how panoramas and contemporary history-writing each represented the Indian Uprising. A central challenge of studying nineteenth-century panoramas is that the original paintings largely do not survive. The canvases were toured into disrepair or painted over, inherently intended as topical ephemera. Most surviving material exists in the form of reviews and other reception, and in paratexts (the programs sold to accompany visitors’ time at the exhibit or performance, and to act as key and souvenir). This article uses these materials both to recover the visitor experience of panoramas and to compare them briefly with contemporaneous would-be historical accounts of the uprising that have been much less read by modern critics than have literary responses.

1. Patriotism and Voyeurism through Panoramas

Panoramas typically celebrated dominant nationalisms, colonialism, and imperialism. The recent historical events they depicted were almost universally military events, and the ones selected were almost universally victories.Footnote 12 They were thus routinely used to stir up patriotic and specifically warmongering emotion. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue that ideologies of empire rely on “the capacity to present force as being in the service of right or peace.”Footnote 13 Such sentiment is not hard to find among the promotional and supplementary materials that survive from panoramas. Let us start with the program to a panorama by Robert Burford of a core episode of the Indian Uprising. The image depicts The City of Delhi, with an Action between Her Majesty's Troops and the Revolted Sepoys (1858). The program opens by describing Delhi as having been

the scene of the most fearful crimes and revolting cruelties that the most atrocious and diabolical natures could conceive—the dreadful but just retribution for which, that has been so quickly inflicted on the perpetrators, forms the principal subject of the present Panorama.Footnote 14

This sentence, initially rich with apocalyptic adjectives, diminishes to a quiet statement of fact that assumes agreement with its approach.

The patriotic emphasis of panoramas might lead us to view them as continuing the eighteenth-century ideological work traced by Linda Colley in Britons and expressing it in an explicit call to action.Footnote 15 However, we cannot assume that visitors swallowed this apoplectic chauvinism whole. John Plunkett envisages panoramas offering a means for those on the mainland of Great Britain to experience “vicarious participation in the event[s]” of the British Empire and its wars.Footnote 16 This partially echoes Benedict Anderson's argument that simultaneous newspaper-reading—about events that are also simultaneous but spatially disparate—helped form national “imagined communities.” Unlike newspapers read “in silent privacy, in the lair of the skull,” however, the panorama was consumed in a very public sphere.Footnote 17 This complicates the experience by allowing space for verbalized disagreements, as we will see in the following pages.

Panoramas were not necessarily singular in their design. Historical representations can often serve multiple purposes, as Billie Melman and Stuart Semmel remind us in their examinations of show culture: such displays can sometimes even cater to two polarized causes.Footnote 18 Building on such work, Denise Blake Oleksijczuk and Joshua Swidzinski have suggested that the very first panoramas (in the late 1780s and early 1790s) could carry subversive implications.Footnote 19 Oleksijczuk and Swidzinski suggest vaguely that panoramas became more subservient to patriotic messages as time went on, whereas Garrison's substantial collection of panorama programs perceives consistent “uncompromising support of the government, military and empire.”Footnote 20 Most analysis of panoramas has focused on the form's early decades; hence the need for analyses such as this one that move into the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Moreover, whatever patriotic or militaristic message panorama painters declaimed, visitors might demur. One important concern was the voyeurism implicit in panoramic celebrations of violence. The psychoanalytic concept of voyeurism—outlined by Jacques Lacan and expanded into film studies by Laura Mulvey—sees “scopophilia” built into the image by its creators.Footnote 21 From early in the history of the panorama, however, visitors worried that voyeurism might lie in the image's reception: that they might be at fault for enjoying their experience. One Reverend Thomas Greenwood was so pained by his visit to a “peristrephic” panorama of the Battle of Waterloo that he wrote a poem that lamented: “Oh! how can I gaze with delight / On a scene so revolting as this?”Footnote 22 Several decades later, in 1841, a Morning Chronicle review reiterated this paradox in relation to a panorama of the contemporaneous Egyptian-Ottoman War. The reviewer jingoistically describes the panorama's depiction of injuries being inflicted on Ottoman gunmen as “a happy thought.” The journalist declares that “it is impossible to see” the painting “without feeling additional pride” at the attack or (he adds, perhaps sheepishly) “without also feeling a desire to repeat our visit to this peaceful exhibition of it.”Footnote 23 Here there is a sharp gap between the warmongering reaction and the “peaceful” situation required for viewing it.

What comes to the fore in both these accounts is disingenuousness. The writers were conscious of celebrating peaceful entertainments that were nonetheless fueled by warfare. And this particular combined approach was only possible because the warfare was taking place overseas. Favret draws attention to the particular problem at the heart of my project,

the dilemmas attendant upon efforts to make history of the present or recent past. How is sublimity accomplished if an event stands close in time but appears to be happening elsewhere, at a remove? Does the sublimity so frequently associated with distance operate differently when temporal and geographical distances do not match up; or, as in the instance of the panorama, when they collapse too violently?Footnote 24

The challenge she highlights here in relation to panoramas of the Romantic period becomes heightened in relation to panoramas of the “Indian Mutiny,” where the precarious balance of temporal proximity and geographical distance collide with intense emotional and political charge. Scholars have persistently debated whether panoramas primarily offer immersion or overview: do they bring the viewer closer to the scene of action or give them a critical distance from it?Footnote 25 Favret argues that panorama programs—especially those that exhaustively labeled their paintings’ contents—attempted to quash debate.Footnote 26 However, exhaustive detail in panoramic representations of recent events did not always leach them of disruptive emotion. In fact, as I will show next, it could heighten them.

2. Representations of the Indian Uprising

Concerns about voyeurism came to the fore in response to depictions of the Indian Uprising. In this infamous episode, both Hindu and Muslim Indian soldiers employed by the East India Company rose up in rebellion. The revolt sparked immediate and savage retribution from the British, and ultimately an overhaul of the way Britain approached and ruled the subcontinent, with power being removed from the East India Company directly into the hands of the British government. What of this traumatic set of events could be depicted in show culture, and what counted as too proximately or gruesomely voyeuristic? And—as asked earlier—was there capacity for divergent versions?

Where divergence emerged, it did so to serve different functions. Jan and Almeida Assmann's definition of two types of collective memory is useful here.Footnote 27 Erll has deployed their distinction between communicative memory and cultural memory to explain the succession of narrative types. Just as memories of the uprising shifted from being informal and personal (communicative) to ossified and monolithic (cultural), initial eyewitness accounts gave way over time to deliberately monumental narratives.Footnote 28 Paxton's work adds the valuable dimension of distance to this analysis. She argues that fiction writers who sought that monumental mode drew upon the genres of epic and chivalric romance “to project very recent events into the distant, absolute past.”Footnote 29 She suggests that the most effective way to construct a sense of distance was through genre. One form missing from both Paxton's and Erll's analyses, however, is the panorama. This medium complicates any bipartite schema of eyewitness accounts vs. romanticized epic, since panoramas used both modes and were comprised of visual and multigenre textual components. Their ability to straddle that apparent genre divide is arguably what made them such powerful historical mediators.

Initial representations of the Indian Uprising were significantly affected—and distorted—by disruptions in communication. British civilians’ expectations about how quickly they might hear from the front lines of warfare had been transformed and heightened in the 1850s. The new technology of telegraphy enabled a newly speedy turnaround of reports from the Crimean War (1853–56).Footnote 30 When the uprising broke out in May 1857, however, any expectations of similar speed were decidedly denied. Even with telegraphy, “news from India took [. . .] about 7 weeks to reach London,”Footnote 31 and this was exacerbated when the rebels cut telegraph wires and disrupted the postal system.Footnote 32 The challenges this caused are vividly apparent across media.Footnote 33 Dion Boucicault's play Jessie Brown; or, The Relief of Lucknow (1858; 1862) was largely based on a single fallacious eyewitness account and spawned a wealth of spin-off theater and iconography.Footnote 34 An 1857 pamphlet acknowledges its limitations more openly, ending with the comment that “Part 2, continuing the narrative, will appear immediately on receipt of Official Intelligence of the Fall of Delhi.”Footnote 35 The history was being narrated as quickly as its source material was arriving, but this was an intermittent and interrupted process.

Perhaps the most significant effect of those bitty and broken communication formats was the latitude it opened up for speculation and rumor. Arguably the best known and most repeated trope from mutiny fiction of the remainder of the nineteenth century is the rape of British women.Footnote 36 Historians at the time and since have converged in emphasizing that there is no evidence of this having happened. While women and children certainly were massacred, historians point out that sexual relations with these white women would have been anathema for their captors, causing them to lose caste.Footnote 37 Gaps in the communications record, however, enabled this rumor to begin and then—in the absence of more concrete information—to spread, proliferate, and become entrenched. The historian and former Indian administrator Thomas Babington Macaulay wrote in his diary on September 19, 1857, in response to news and rumors from the Indian subcontinent: “It is painful to be so revengeful as I feel myself.”Footnote 38 Macaulay was certainly not alone in his drive for vengeance.Footnote 39

That does not mean, however, that calls for vengeance were universal or exclusive. A plethora of pamphlets emerged in immediate response to reports from India, which were notably self-flagellating and blamed British actions for the outbreak.Footnote 40 Examples such as William Sinclair's The Sepoy Mutinies; Their Origin and Their Cure (1857), George Crawshay's The Immediate Cause of the Indian Mutiny (1858) or G. B. Malleson's The Mutiny in the Bengal Army (1857), better known as the Red Pamphlet, were an important first stage in the mediation of events toward historiography, since they were formally freestanding and less speedily superseded than a newspaper or periodical article. Malleson declares—in patronizing but protective mode—that “with proper management, the Sepoys are brave, useful and decidedly cheap soldiers,” suggesting that this “proper management” had been lacking.Footnote 41 Several pamphlets, including Sinclair's, blame this on “the tendency to centralization” and a removal of power from the army commander-in-chief to the civilian governor general.Footnote 42 George Crawshay, mayor of Gateshead, argues that “since the institution of the Board of Control by Mr. Pitt, the governing power has not been in the hands of the East India Company, but of the Board of Control, which is simply an alias for Prime Minister.”Footnote 43 In this version of events, the East India Company had long been a puppet of the UK government (such that stripping the company of its powers would not solve any of the underlying problems in British India). Crawshay even draws on Indian religious imagery to illustrate his point, declaring: “You bow down before the Minister as the Hindoo bows down before Juggernaut.”Footnote 44 This bold image suggests that the acquiescence is overly passive and abnegates too much responsibility, and even that it might result in the worshipper being crushed. He also dangerously suggests that any asserted difference between British and Indians might be illusory after all. Overall, these pamphlets demonstrate that immediate written responses to the uprising were not solely vengeful or jingoistic. How did panoramas of the time compare?

3. 1850s Panoramas of the Uprising

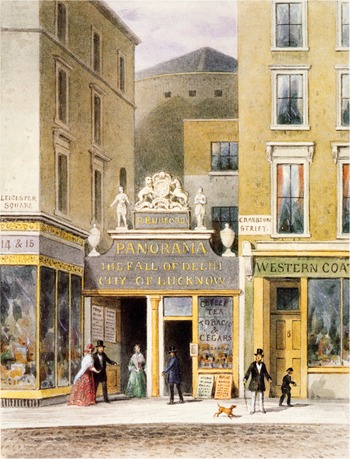

Panorama painters were, like playwrights and pamphlet writers, quick off the mark in representing the Indian Uprising. At the most long-standing panorama rotunda at Leicester Square, Robert Burford and colleagues devoted both floors to the topic for a year each. As figure 1 illustrates, the large downstairs circle illustrated The City of Delhi, with the Action between Her Majesty's Troops and the Revolted Sepoys (from January 1858), while the smaller upstairs circle showed the City of Lucknow (from March 1858).Footnote 45 Since the British heyday of the 360-degree panorama had been the 1790s to 1820s, this is the only pair of mutiny panoramas in this format I have identified.Footnote 46 By contrast, the circular panorama's sibling forms, such as the scroll-based moving panorama and the light-effect diorama, were still going strong. Erkki Huhtamo has brought these to scholarly attention and shown that because they were designed to be portable, they were seen by many more people than were their circular siblings.Footnote 47 He does not discuss the ones produced in response to the Indian Uprising, but these began as early as September 1857, when Hamilton's Great Original Historical Panorama of India (1857), probably the joint creation of four brothers, opened in northwest England and then toured much of the UK. “Mr. Marshall” (probably Charles Marshall, 1806–1890) displayed a “panoramic view” of Delhi at the Auction Mart in the old City of London. Marshall's painting of Delhi then seems to have been incorporated into Gompertz's Grand Historical Diorama of the Indian Mutiny, which opened in May 1858 at St James's Hall, Piccadilly, and subsequently went on tour.Footnote 48

Figure 1. T. H. Shepherd, Cranbourne Street, Entrance to Burford's Panorama (1858), © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Huhtamo argues that while the circular panorama “emphasized immersion,” the moving panorama prioritized “narration and combinations of different means of expression.”Footnote 49 As I will show, however, that was also true by this period for the circular panoramas. The following analyses examine both what each of these panoramas depicted and how that was presented. Did the images show graphic violence, in ways that viewers then and/or now might interpret as voyeuristic? Second, was this violence (against British or Indian people) presented with the aim of stirring up militaristic sentiment that we would see as jingoistic? Such messages were particularly imparted through paratexts, which are also the predominant surviving elements of this multimedia phenomenon.

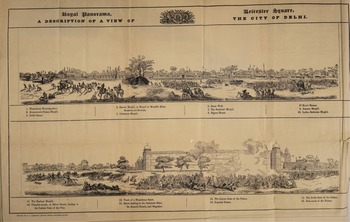

Burford's 1858 The City of Delhi, with an Action between Her Majesty's Troops and the Revolted Sepoys is the only one of these with a surviving program, including a full-page engraving of the 360-degree painting (in two halves; see fig. 2). It showed only “a single slice of time,” but what the image lacked in narrative capacity, Burford sought to make up for in its paratext.Footnote 50 The program's message is patriotic and sufficiently upbeat to feature an advert for finely tailored “Marriage Outfits Complete,” including “the inexpensive things required for the ‘Indian Voyage.’”Footnote 51 Prospective Anglo-Indian wives nonetheless might have quailed upon reading the program. From its outset (as we saw in part 1), it asserts the British siege of Delhi as necessary, due to what it claims were the Indian Uprising's aims “to exterminate, without any exception, every Christian in India.”Footnote 52 In an uncanny mirror image of this statement, however, the program's narrative concludes:

During the assault, sixty [British Army] officers fell killed or wounded, and one thousand one hundred and seventy-eight men were put hors de combat, and in the previous three months’ siege, upwards of two hundred officers and four thousand men were killed or severely wounded. The number of the enemy who were killed, for no prisoners were made, is not, nor, perhaps, ever can be known, but it must have been enormous.Footnote 53

Figure 2. The full-page engraving in the program of Burford's View of the City of Delhi (1858). Reproduced with permission of Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (1363-628). Digitized by Internet Archive. Hosted online by the Hathi Trust: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102503368.

Nathan Hensley has recently delineated how nineteenth-century British bureaucracy, fueled by the logic of liberalism, sought to “enumerate” and catalog its inhabitants, turning families into citizens in a process of what Foucault would call biopolitics. In this situation, “the only thing worse than counting is not to count at all.”Footnote 54 We see exactly this happening in the comparison of British and Indian lives lost: the British lives, registered by the army and therefore notable when absent, are precisely detailed; by contrast, the “enemy” lives are an “enormous” uncanny absence. On the canvas itself they are only represented by the occasional slumped corpse, whose faces are discreetly turned away from the viewer.Footnote 55

The program of Burford's City of Delhi panorama is by no means solely a historical account. In fact, that statement about war dead is immediately followed by a lurch of register, as the chronicler gives way to the tour guide. The next sentence invites us to shift our gaze from the battlefield foreground to a linear cityscape in the middle distance. We get a substantial introduction to the key geographical features of Delhi (“There are seven principal gates . . .”) and then a numbered key to the panorama engraving [see fig. 1], which exclusively labels static features in the background of the image (“Cashmere Street,” “Jumma Musjid”) rather than identifying the details of the fierce fighting taking place in the foreground.Footnote 56 As a review in the Times put it, while “the chief objects [are] groups” of soldiers fighting, “the opportunity of showing the architectural wonders of the place has not been lost.”Footnote 57 While we might see this as disingenuous distraction, the Times seems to approve.

This single panorama image, therefore, combines two types of historical illustration. These are what Stephen Bann has valuably delineated as “metonymic” and “metaphoric,” where the former displays a surviving relic of the past, and the latter an imaginative re-creation of past events.Footnote 58 In this image, the background is metonymic (the city as artifact for inspection, probably based on sketches from before the uprising), whereas the foreground aims to re-create eyewitness accounts. (The two layers visually intersect at only one point, where a palace wall is shown succumbing to artillery fire.) The program itself, however, describes the foreground events as “many interesting incidents and sanguinary single-handed encounters, which, although they did not actually take place at the precise time, or on the exact spot, have, with an artist's license, been introduced to give greater spirit and effect to the scene.”Footnote 59 This requires us to revise our definition of Bann's two categories, since even the “metaphoric” portion of the image is designed for visitor appeal rather than to re-create any single or plausible historical moment. Despite the much-lauded realism of the panorama form, what this panorama offers is a combination of symbolic elements.

Jingoistic messages are implicit even in the program's tour-guiding section. Number 1 in the key tells us that a visually inconspicuous patch of ground (on the top left of fig. 1) is a “Mussulman Burying Place.” That section of the program is then devoted to detailing a 1739 massacre by the Persian emperor Nader Shah that apparently killed “about 120,000 persons.”Footnote 60 This description of a Muslim-invader massacre of Muslim inhabitants deflects attention away from the description (two pages previously) of the uncountable inhabitants killed by the 1857 British siege. It suggests that violence is in fact inevitable in Delhi. This inclusion in the program shows how co-dependent but arguably asymmetrical were panorama and paratext: a viewer could not have gleaned this story from the image alone. Here the paratext adds a layer of previous historical context and implicitly uses it to justify both the use of violence in retribution against the uprising and a longer-term imperial civilizing mission. There is an anxious chauvinism to the program that those visitors who did not spend sixpence on it would not necessarily take from the painting alone. On the other hand, for those who did purchase and read it, that chauvinistic reading of the image would be hard to shake off.

The other panoramic image we have of the city under siege, Mr. Marshall's Panorama of Delhi (September 1857 onward), is more critical of British actions. There is no known surviving print or paratext of this panorama, so we have to rely on reviews. These tend to highlight its limitations: The Critic queries its panoramic status, describing it as “only a large oblong picture,” while the Daily News says it was “painted from drawings made some time since on the spot”—implicitly, before the uprising.Footnote 61 However, both see it as informative. The Critic describes it showing “alas! more clearly than ever, the difficulties which the British force has to encounter, both in defending its own position, and in carrying that of the wretched fiends now in possession of Delhi.”Footnote 62 The Daily News reads this painting more as an implicit commentary on British mismanagement:

The whole city is surrounded by strong walls seven miles in length. . . . For this the mutineers are indebted to the wise provision of the hon. company, as also for the two heavy siege trains, and the almost boundless store of ammunition with which they are now so liberally peppering her Majesty's troops. It is impossible to avoid being struck with the wisdom of the governing body which could thus carefully prepare a city to become the key of the military occupation of a conquered province, and then liberally hand its custody exclusively over to the conquered inhabitants. It was a magnificent instance of generosity, and the only regret is that it has not been met by a sympathizing return.Footnote 63

This journalist evidently does not receive the panorama as an endorsement of British government policy. This is, however, only partially subversive on the model argued for by Oleksijczuk and Swidzinski. What the Daily News critiques is not the violence involved in British retribution. Instead, this reviewer questions the undue trust previously placed by the East India Company in those would-be “mutineers.”

Hamilton's Great Original Historical Panorama of India was a moving panorama produced by four brothers “on 30,000 square feet of canvas.” This was one of the most immediate and well-traveled panoramas, touring from Liverpool and Manchester to Scotland, Ireland and southwest England over the eighteen months from September 1857. Its scroll format enabled it to offer a combination of attractions. An advert opens by promising “the gorgeous Scenery of HINDOSTAN, its Palaces, Temples and the Manners and Customs of the Hindoo Inhabitants—introducing the most IMPORTANT SCENES AND EVENTS IN THE INDIAN MUTINY, Etc.”Footnote 64 Although the advert's opening gambit highlights in bold type the panorama's topicality, the rest of the description emphasizes more timeless delights: “In the towns and villages are seen the inhabitants, natives and Europeans, of all castes and grades, dressed in their characteristic costumes, engaged in their customary business, domestic occupations, RELIGIOUS CEREMONIES, PUBLIC FESTIVITIES, and SOCIAL AMUSEMENTS.” The fragmentary evidence of this advert and reviews does not enable us to know exactly the balance in this set of paintings between the historical and the scenic, but it is an important reminder that panoramas routinely offered both. While in Burford's 360-degree panorama both were compressed within the same image, moving panoramas tended to intersperse the two modes. In the case of Hamilton's panorama, reviewers prioritized different elements. A Liverpool review argued that its value came from showing “the scenes of the most atrocious crimes ever recorded,” whereas an Aberdeen review expressed distaste for precisely those elements, commenting that “(with the exception of one or two of the scenes depicting the massacre) it is really a beautiful work of art and worthy of all praise.”Footnote 65 Meanwhile, a Glasgow review commented approvingly that “the number of such scenes is judiciously limited in a panorama of this kind.”Footnote 66 Evaluations of violence in panoramas—and whether that was seen as gratuitous or necessary—were highly variable and dependent on audience.

The 1858 dioramic moving panorama by Moses Gompertz was probably the most contentious of them all. Like Hamilton's, it was a scroll-based attraction comprising multiple sequential images (including incorporating Marshall's painting of Delhi).Footnote 67 It therefore sought to range across all the episode's key events and included scenes of massacre. The handbill presents the uprising as exciting (subheadings include, in different typefaces, “BATTLE OF SUBZEEMUNDIE!” and “PESHAWUR!”) and sought to combine topical drama and sublime natural relief. The description following “PESHAWUR” reads:

In the view here presented we have a representation of the way in which numbers of the Mutineers were put to death [most likely the infamous practice of shooting them from cannons]. In the foreground, Colonel Edwards is superintending the execution. The famous Kyber Pass is seen to the left of the view, the summit of which is 3373 feet above the sea level, and 2200 feet above Peshawur. In order to vary the character of the Diorama, and relieve the eye and mind of the Spectator from the excitement attendant on the subject of war, a section of that sublime mountainous scenery which characterizes the Northern portion of Hindostan is here introduced.Footnote 68

The inclusion of the “famous Kyber Pass” within the execution scene itself suggests that—more like Burford than Hamilton—Gompertz was trying to cohere both types of attraction into single canvases. There are also stark sequential contrasts within the show: after some “sunset” and “moonlight” landscape delights, we return to the “ASSEMBLY ROOMS AT CAWNPORE” (an environment not so different from those in which the diorama might be viewed) “in which took place the awful Massacre of English Women and Children, by command of Nana Sahib, on the 15th of July.” The diorama thus combined generic, aesthetically pleasing light-effects with very recent and distressing history.

Unsurprisingly, it did not meet with universal approval. One reviewer in the Illustrated London News complained about its graphic violence and called for it to be removed:

In this revolting picture we see a confused mass of Englishwomen vainly struggling against the cruel fate which awaits them, or having already succumbed to it. Some are being dragged by the hair of their heads, their clothes partly torn off; others are being bayoneted as they sink overpowered to the ground; in another part children are being thrown up into the air to be caught upon bayonets when they descend. In short all these most sickening incidents of that dark and dismal scene are delineated, and the lecturer expiates them seriatim. . . . We can only hope that in deference to those feelings the picture will be withdrawn.Footnote 69

We cannot know the message that Gompertz was trying to impart—to what extent his gruesome images were accompanied by jingoistic or otherwise-pitched lecture commentary—but the ILN journalist sees the show's voyeurism as superseding any other informative or sympathy-inducing functions. A twenty-first-century reader might see this as implicitly recognizing the problem diagnosed by Mulvey (1975) as that of scopophilia and—in gendered terms—as the male gaze. We nominally look at this “vain struggle” and “cruel fate” from a distanced external perspective. However, through watching (and especially through the elaborations of the complicit lecturer), we are forced into the much more proximate position of the Indian onlookers or even perpetrators. In effect, we collaborate in the sadistic violence forced upon these women.

The ILN was not alone in its discomfort. The Daily News comments more forgivingly that in the Cawnpore massacre canvas, “great pains have been taken to render the picture as little revolting as the subject will allow.”Footnote 70 This seems to draw on a quotation from the show itself, reprinted in the Morning Post: the painting, “we are informed, ‘occupied a considerable time in preparation, owing to the difficulty experienced in treating a subject of so painfully interesting a character, so as to avoid shocking the feelings of the most sensitive.’”Footnote 71 The Morning Post’s reviewer nonetheless concludes:

we are of opinion that it requires the intervention of some 40 or 50 years before the subject can be successfully treated, as its horrors are too recent, and we feel there are too many relatives of the unfortunate ladies massacred upon the occasion still alive to allow the scene being brought before the public excepting in the worst of taste; and, however well executed (which we do not for a moment deny), we should recommend that this portion of the diorama be at once withdrawn.Footnote 72

Whatever pains were taken to minimize the gratuitous voyeurism of the painting, the Morning Post sees the creators’ and viewers’ level of chronological and emotional distance as unavoidably insufficient.

The show was nonetheless a commercial success: the outcry perhaps generated profitable fascination. The following week, ILN noted: “M Gompertz respectfully announces that in consequence of the great rush of spectators to witness the New and Gigantic DIORAMA of the INDIAN MUTINY, the room being so crowded that numbers are nightly refused admission, he has arranged to keep the Exhibition open for a Fortnight longer.”Footnote 73 Three weeks later, ILN printed summary confirmation that the show would “be given daily until further notice.”Footnote 74 The show then toured extensively, at least around the southwest of England, to Jersey and to Dublin.Footnote 75 A review from Devonport suggests some change of content, since it comments:

We recently paid a visit . . . and were most agreeably surprised, in the first place to find the exhibition so entirely divested of the painful and horrible scenes enacted in this terrible rebellion, and at the same time to find all the great events of this fearful period so vividly pourtrayed [sic].Footnote 76

The term “divested” might merely indicate a distance from the reviewer's own painful memories of the mutiny, or it might imply that Gompertz responded to London criticism by toning down or removing some of the violent scenes. Panorama painters evidently could not rely on geographical distance to substitute for lack of temporal distance from the events they depicted. Audiences were still very emotionally proximate.

It was, however, easier to condemn voyeurism than to avoid it. The very issue of ILN that carried the critical review of Gompertz's diorama also had an article about the latest in the quashing of the rebellion. Quoting wholesale another from the Bombay Standard of a month previously, it states that “With the capture of Lucknow the curtain drops on the grandest scene of the bloody drama.”Footnote 77 Although Gompertz's reviewer chastised him for voyeurism, it seems that the metaphor of the mutiny as a theatrical show was irresistible. Richard Terdiman has described newspapers as “the first culturally influential anti-organicist mode of modern discursive construction,” but here the ILN shows how nominally unrelated articles can illuminate and potentially undermine one another.Footnote 78 Although ILN condemned the voyeurism of the show culture generated by the Indian Uprising, it was similarly saturated with imagery that puts those events in theatrical terms.

All this voyeurism, conscious and otherwise, raises some pressing questions: can the panorama be a justifiable format for “news”? And if not, what is the cutoff point: when does the Indian Uprising become acceptable as entertainment, or suitable for assimilation as history? In partial answer to the first: the image in which the theatrical “curtain drops” suggests that these events are merely ephemeral, and thus that our attention to them can be similarly ephemeral. Favret argues that “war at a distance” is mediated in part through microperiodization such as “today's news occluding the news of yesterday.”Footnote 79 As Clare Pettitt has more recently put it, as daily news became a possibility in the 1830s and 1840s, “yesterday's news” came to “seem . . . more distant.”Footnote 80 As dispatches and updates resumed their regularity after the uprising, therefore, one could more quickly disregard the previous edition. In the theatrical metaphor common to both ILN journalists, the “Indian Mutiny” becomes a gruesome play, thankfully over; now we can all go home.

The ILN also passed judgment on that second question of when the Indian Uprising could be considered as history. In January 1860 (two and a half years after the first outbreak of uprising, and six months after peace was formally declared), an article described a new “Delhi and Lucknow Medal.” We read: “This characteristic testimonial of the Indian Mutiny (which may be regarded as the final incident) has now been struck at her Majesty's Mint in silver, and is now in course of distribution.”Footnote 81 The medal and the article about it attempt to draw a line under the proceedings, declaring the rebellion's “final incident” to be the production of a material object over which the Crown has both practical and symbolic control. And a year later, in April 1861, the paper was declaring that the uprising was now history. A review of a published eyewitness account opens:

Although the occurrences of the Indian mutiny have passed into the category of history, it is well that the writing of that history should not be delayed too long. The lesson and the example which the events of 1857 afford are such as ought to have a direct and continuous influence on our governmental and social policy in India.Footnote 82

According to this journalist, the events and their evidence had now ossified sufficiently that a “lesson” (unspecified) could be learned from them.

4. Initial Illustrated Histories

Accounts of the uprising that called themselves “histories” did indeed start appearing within a very short period: by the time of that 1861 ILN article, there had already been two. The first self-styled histories of the mutiny, which deployed the experiential mode, were a pair of illustrated narratives by Charles Ball (1858–59) and R. Montgomery Martin (1858–61). As Herbert delineates, these were produced by the same publisher and intended as a complementary pair, but they took quite different tones: Ball's offered “an almost fantastic superabundance” of information and was overtly jingoistic, though also “rife with imagery of the sickening ugliness of British reprisals.”Footnote 83 By contrast, Martin's was “a violent critique of the patriotic and triumphalist myth of the war that Ball strives, however conflictedly, to set forth for posterity.”Footnote 84 What unites Ball's and Martin's histories is a dramatic style that was shared across their rhetoric and their illustrations, which latter Herbert does not discuss. Both texts feature substantial sets of uncredited engraved plates, many of which were repeated across the two publications. As was the case in moving panoramas and dioramas, some of these showed vistas of Indian landscapes, while others depicted recent events.

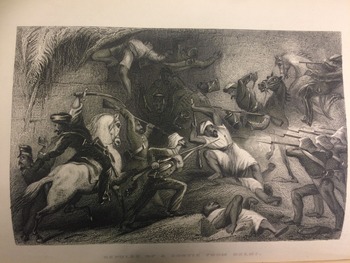

Some of these illustrations drew their iconography from stage sets. The shared set of plates includes the well-known Miss Wheeler Defending Herself against the Sepoys at Cawnpore (reproduced on the front cover of Jenny Sharpe's Allegories of Empire) and one entitled Repulse of a Sortie from Delhi. These both feature solid walls behind the action that curtail the viewer's eyeline, limiting these images to a very shallow plane.Footnote 85 The Repulse of a Sortie from Delhi (fig. 2) even includes flat, masklike outlines of Indian soldiers in the shadows at the center of the image, making them little more than cartoon villains. Apart from a glimpse of an exotic palace dome in one corner of the Miss Wheeler image, these images are “space-drained.”Footnote 86 They only have foreground and are thus explicitly nonpanoramic. Instead, they echo the interior stage sets of melodramas such as Boucicault's Jessie Brown. They offer not historical distance but emotional proximity and demonization of the enemy.

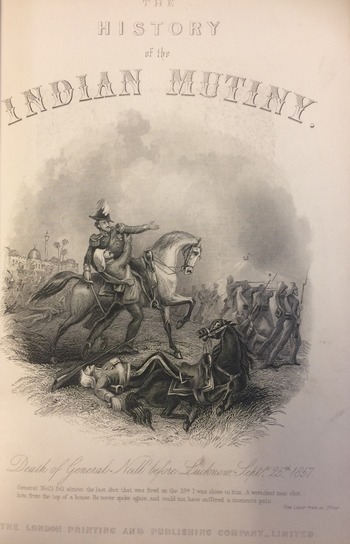

Others of these illustrations are clearly influenced by panoramas. These include many plates of wide vistas, recorded from an elevated viewpoint and stretching to a distant horizon. Also (though differently) panoramic is the frontispiece of Ball's History of the Indian Mutiny: puzzlingly, different editions give it different captions, so that one copy notes it as “Sir Henry Lawrence Mortally Wounded before Lucknow,” while another pronounces it to be the “Death of General Neill before Lucknow” (fig. 3).Footnote 87 This uncanny substitution (both did indeed die at Lucknow) suggests that the specifics of historical figures or events are less important than their patriotism-inducing iconography. The engraving shows influences from both history-painting and stage iconography. Like classical history-painting, it has a hero front and center, and the title (in both contradictory versions) declares it to be a painting of a single man. Nonetheless, several other pockets of action coexist simultaneously: fierce fighting on the left, and on the right, soldiers marching steadily toward and beyond the edge of the page. This is not a history-painting in the model of Benjamin West's Death of General Wolfe (1770) or Death of Nelson (1806), where all significant attention is focused on the dying hero. The multiple dynamic scenes, which disperse the viewer's interest across several vignettes, are reminiscent of the panorama; the scenes are so disparate that they most closely evoke a scrolling “moving panorama.” These examples demonstrate that not only did panoramas represent contemporary history; the visual grammar of the panorama also made its way into immediate illustrated histories. As I show in my current book project but lack space to explore here, historians often also adopted a rhetorical version of panoramic perspective to help them write their narratives of recent events.Footnote 88 There was therefore a reciprocal relationship between panoramas and contemporary history.

Figure 3. Repulse of a Sortie from Delhi, illustration in Charles Ball, The History of the Indian Mutiny (1858), vol. 1, facing p. 461. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Archives & Special Collections, shelf-mark Store 29766, https://eleanor.lib.gla.ac.uk/record=b2191906.

Figure 4. Sir Henry Lawrence Mortally Wounded before Lucknow, frontispiece to Ball, History of the Indian Mutiny, vol. 1. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Archives & Special Collections, shelf-mark store 29766, https://eleanor.lib.gla.ac.uk/record=b2191906.

5. 1870s Panoramas of the Uprising

With greater temporal and emotional distance, the imagery of the Indian Uprising became increasingly standardized. Touring panorama shows reused content and even canvases between one display and another, a practice that highlights the different expectations of different genres and forms. When written narratives of the Indian Uprising display repetition, scholars view this as a problem. Herbert describes the exhaustive detailing of violence in Charles Ball's The History of the Indian Mutiny (1858) as “almost overwhelming repetitiveness,” while Nancy Paxton comments that “one of the most extraordinary features of novels about the Indian Uprising of 1857 is their similarity.”Footnote 89 Turning to show culture, Tracy Davis has argued that our criteria for evaluating nineteenth-century performance practice places such a high “premium on claiming originality, innovation, and marked changes that we are ill-disposed to acknowledge derivation, consistency, or comparability.”Footnote 90 There was frequent repetition in provincial panoramas of the latter half of the nineteenth century, but Plunkett, drawing on Davis, views this as a “mark of success” and indication that showmen had found “a format that would guarantee audiences.”Footnote 91

Later panoramas rehashed the imagery we have already encountered. A Birmingham Daily Post article about an 1870 moving panorama describes it as depicting two topics:

the chief incidents of the Great Indian Mutiny, and the earlier travels of Dr Livingstone in South Africa. In the first portion of the entertainment are comprised views of the beautiful city of Delhi capital of the Mogul Empire, with the British encampment before the walls, the punishment of mutineers, Sepoys blown from the cannon's mouth, the siege, storming, and final capture of Delhi; Lucknow, and the various incidents of the siege and relief of that city, and the triumphal meeting of the three British Generals, Sir H. Havelock, Sir Colin Campbell, and Sir James Outram.Footnote 92

The only identifiable shift is a transfer of attention away from the massacre of women and children, toward the military efforts of men. Here the mutiny is subsumed into a sequence of key imperial moments, part of the “white man's burden” that also included Dr Livingstone's exploration, mapping, and expansion of imperial territory. The list of elements here—“the British encampment . . . the punishment . . . the siege,” especially with their definite articles—shows what standard, familiar tropes these had become by the 1870s.

This is also true for an 1878 “moving diorama” by a Mr. E. Bennett, running “for two nights only” at the Horns Assembly Room in Kennington. A surviving handbill advertising the show describes it “forming a brilliant panorama from Charing Cross to Cabul” and allowing the viewer to “witness many sights and scenes of thrilling interest, in OUR INDIAN EMPIRE.”Footnote 93 As Gompertz did previously, Bennett mingles the grim episodes of the uprising with more static tourist sights such as “Benares from the Ganges” and “The Kaiserbagh, with its old mixture of architecture.” Even the site of 1857's infamous massacre is described as “The Charming City of Lucknow.” But we still get, toward the end of the list:

THE BELEAGUERED CAPTIVES,

A Scene of Thrilling Interest,

RELIEF OF LUCKNOW,

“The Campbell's are coming.”

Heroism of an English Lady

Reminiscences of the Indian Mutiny.

“The Campbell's [sic] are coming” gives us an echo of Boucicault's Jessie Brown (1858; 1862).Footnote 94 In that play, the penetrating bagpipe notes of the Highlanders gives those “beleaguered captives” their first clue of impending relief.Footnote 95 The handbill's shorthand suggests that these would still have been familiar tropes to the diorama's visitors. Confirming Davis and Plunkett's analyses, show culture of the uprising is thus notable for its repetition rather than inventiveness or radicalism. The distorted and one-sided representation of events clearly served a powerful function in helping communicative memory to ossify into cultural memory, allowing the episode to become undisputed myth for British audiences.

6. Conclusions

Since none of the paintings studied here survive, this article's combination of paratexts, adverts, and reviews and other newspaper responses reconstructs a show culture that would otherwise remain inaccessible. I have likewise demonstrated both the necessity and the significance of examining nineteenth-century panoramas through and with their paratexts. These displays were multimedia phenomena, and the messages in their programs (often all that survives) amplified, elaborated on, and sometimes diverged from those in the image itself. From some of these panoramas, even less survives, leaving only advertising material or reception. However, examining this reception can be valuable in highlighting that audiences did not always take vitriolic representations at face value.

These sources show that contrary to the vituperative tone in sources such as Dickens's and Collins's Perils of Certain English Prisoners (1857) and subsequent novels, public opinion at the time was more nuanced. Pamphlets were published that were highly critical of the East India Company's policies and blamed the outbreak of the rebellion on British behavior. Similarly, journalists’ responses to visualization of the uprising were decidedly mixed. Reviewers repeatedly expressed discomfort with the voyeurism of panorama images, though not with their jingoism, and this does not necessarily seem to have diminished visitor turnout.

Plunkett suggests that panoramas “could appeal as much to those who decried military conflict as to those who gloried in Britain's free-trade imperialism,” a reading in which panoramas invited plural interpretation.Footnote 96 My case studies have shown that panoramas of contemporary historical events could appeal to those with a range of reasons to visit and a spectrum of political leanings. However, they circuitously but ultimately contributed to generating, solidifying, and later buying into the myths of the “Indian Mutiny.” Where they resisted chauvinistic displays of violence, it was more to mitigate criticism or to distract audiences with sublime landscapes than to offer any concerted “countermemory.”

While Herbert has valuably shown that British journalists’ and historians’ responses to the uprising were anguished as well as hostile, this article adds an important corrective by showcasing how this same episode was also transformed into entertainment. Examining the details of that show partially extends Herbert's findings to another medium but also shows that anguished reactions did not prevent audiences from choosing to embrace those experiences. Visiting a panorama was perhaps one way to bring that geographically distant but emotionally proximate overseas rebellion physically close.

Surveying a broad array of panoramas from 1857 to the late 1870s shows that as time went by, the uprising content of panoramas became increasingly standardized and audiences apparently less fearful of potential voyeurism, as that “epic of the race” receded into mythic outlines. Contrary to what Salber Phillips's hypothesis might suggest, and more in line with memory studies theory, a few decades’ chronological distance from the “Indian Mutiny” led to a more unquestioning jingoism, rather than more emotional openness. This highlights that chronological distance is insufficient without a change of outlook: here the eventual fall of empire and process of decolonization is a more significant pivot point than any specific length of time.

The results traced here suggest that voyeuristic violence in panoramas would have a similar ideological result whichever way it was received. In the case of the Indian Uprising, either graphic depictions would stir up outrage against the rebels, or viewers horrified at those depictions (like the 1858 ILN reviewer) would claim a moral high ground, emphasizing the events’ weightiness even further. Either way, the upshot is ideological justification and endorsement for the retaliatory violence of 1857–58 and the longer-term imperial reorganization. It raises the question: what would an uprising representation have to do to send a critical or, alternatively, a reconciliatory, antiviolent, message? Some of the pamphlets outlined above attempted such a thing, and more recent writers and artists have played with the panorama form to offer alternatives.Footnote 97 It may not have been possible within the form and genre horizons of the nineteenth-century panorama.