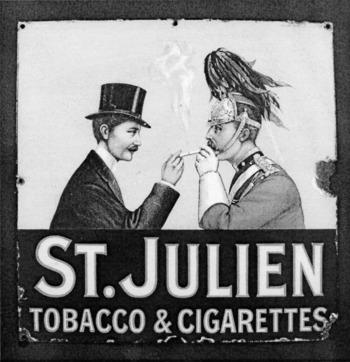

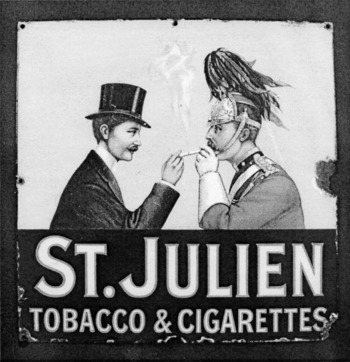

This article explores the position of the guardsman within the symbiotic process through which masculinities and Britishness were constituted and contested in the twentieth century. It takes as its starting point a physical trace of the material culture of early twentieth-century consumerism: an advertising enamel for St. Julien Tobacco and Cigarettes (fig. 1). A cavalryman, striking in scarlet jacket and helmet, leans forward, lighting his cigarette from that of a top-hatted gentleman. Seeking to orchestrate a specific form of consumption, the enamel taps into a potent image of nation and manhood: the cavalryman as soldier hero.

The soldier hero, as Graham Dawson suggests, is “one of the most durable and powerful forms of idealized masculinity…. Military virtues such as aggression, strength, courage and endurance have repeatedly been defined as the natural and inherent qualities of manhood…. Celebrated as a hero in adventure stories telling of his dangerous and daring exploits, the soldier has become a quintessential figure of masculinity.”Footnote 1 Certainly by the late nineteenth century, when “the deeds of military

Fig 1. —The iconic soldier hero

heroes were invested with the new significance of serving the country and glorifying its name,” this figure occupied the “symbolic centre” of Britishness. These narratives were “myths of nationhood itself…a cultural focus around which the national community could cohere.”Footnote 2 Set against this powerful psychic investment, the invocation of the soldier hero offered men the tantalizing imaginary prospect of acquiring these masculine attributes through association. Smoke St. Julien, and you, too, can be a real man.Footnote 3

However, the encounter depicted here has a very different resonance, knowingly evoking an erotic fantasy of masculine physicality—the guardsman. For if the guardsman was a soldier hero, he could also be a rent boy, his Brigade's military exploits matched by equally distinguished traditions of exchanging sex for money and consumerist pleasures with older, wealthier men. This was an institutionalized erotic trade, an arresting feature of London's sexual landscape into the 1960s.Footnote 4 To the cognoscenti, the imagined encounter between civilian and serviceman is thus ubiquitous: the two exchange a sexually charged gaze, and the passage of light amid clouds of smoke is a potent sexual image and a commonplace pickup tactic.

The St. Julien enamel thus explicates wider cultural forms within which the guardsman became central to two specific fantasies of masculinity, extravagant visualizations of what he symbolized and represented. Yet these fantasies were unstable and contradictory, existing in a constant tension through which one persistently threatened to disrupt the other. From mounting guard outside the royal palaces, the guardsman could—and often did—pass easily through those spaces that constituted London's queer underworld, seeking those sexual and social pleasures his erotic allure enabled. That he could oscillate between the symbolic tropes of soldier hero and rent boy produced an instability of meaning that made the guardsman central to the imagined landscape of British masculinities.

This definitional instability echoes Kathleen Canning's positioning of the body at “the connections and convergences of the material and the discursive.”Footnote 5 As Canning suggests, these persistent elisions simultaneously render the guardsman a problematic object of analysis and open wider social formations to exploration. Remarking on her inability to “fix” the body, Judith Butler gestures toward these problems and possibilities: “Not only did bodies tend to indicate a world beyond themselves, but this movement beyond their own boundaries, a movement of boundary itself, appeared to be quite central to what bodies ‘are.’ ”Footnote 6

This article thus explores the divergent and problematic meanings invested in the guardsman. Through the pageantry of state ceremonial, manifested in London's public spaces and reproduced in guidebooks, the guardsman's body was animated as a proxy for national identities in general and hegemonic masculinities in particular. The insistent production and consumption of the soldier hero, I argue, addressed, and answered, the symbolic question of what it meant to be British. In the cultural practices encapsulated by the lingering descriptions of guardsman in the writings of Joe Ackerley, John Lehmann, and others, however, that body was animated by its investment with very different imaginative resonance. The insistent production and consumption of the eroticized guardsman addressed, and answered, the question of what the ideal man might be.

In the twentieth century, the guardsman has thus come to represent both the British nation and an object of queer desire. Nevertheless, throughout the familiar cultural forms that seek to render him knowable, one voice is conspicuous only in its absence. In guidebooks and memoirs alike, the guardsman rarely speaks for himself. He is simply an object of fantasy and imagination. His body is, in Canning's terms, a “passive inscriptive surface” onto which meaning is projected, a “signifier or allegorical emblem” of nation and social and sexual formations.Footnote 7 I do not want to suggest that there is an authentic guardsman's voice to be “recovered,” but to explore the ways that this body problematized the meanings inscribed upon it. Embedded in hegemonic social and sexual practices within the Guards, this was a recalcitrant body that persistently refused to play its allotted role within these fantasies of masculinity.

It was through this trialectic symbolic encounter between soldier hero, rent boy, and queer that particular British masculinities were produced and contested. Those masculinities forever remained unstable, for the guardsman's simultaneous and dissonant status generated profound anxieties. If the embodiment of British manhood could participate in homosex, the nation's gendered body was threatened.Footnote 8 This article thus moves to explore how civil and military authorities, as well as public commentators, negotiated these anxieties, focusing upon the silences and evasions through which the guardsman's sexual and social practices were represented and the disciplinary practices through which hegemonic masculinities and notions of Britishness were articulated and maintained. Symbolically and practically, these strategies sought to protect the soldier hero's integrity, constituting rigid boundaries between guardsman and queer to ensure that the former did not become a rent boy.

In the simplest sense, this article takes up Jeffrey Weeks's suggestion that the analysis of “male prostitution” can “illuminate changing structures of homosexuality,” focusing upon the guardsman in order to explore the ways in which masculine sexualities were definitionally produced and male subjects constituted as different.Footnote 9 Yet, more than this, the coalescence of fantasies of Britishness, masculinity, and sexuality upon the guardsman, I argue, bridges political histories and conceptions of nation, on the one hand, and the engagement with gender and sexualities that has characterized cultural history, on the other hand. The guardsman offers a key both to the cultural politics of masculinity and sexual difference and to the gendered and sexual production of Britishness.

Changing the Guard at Buckingham Palace

If, in 1937, a visitor had opened H. V. Morton's London: A Guide for knowledge of this unknowable metropolis, he or she would first have encountered a black and white photograph—“The Lifeguardsman of London.” Opposite the title page, an imposing uniformed figure sat immobile astride his horse, the upward-directed camera rendering the viewer dwarfed below this spectacle. Seeking to evoke London's essence for the tourist, Morton found in the lifeguardsman a proxy for its rich traditions, the symbol that embodied an imperial city at once ancient and modern.Footnote 10

In so doing, Morton reflected popular mentalities, for the Brigade of Guards were in the forefront of state pageantry, a spectacular ceremonial calendar avidly consumed by Londoners and visitors from provincial Britain and beyond. As Henry Legge-Bourke commented of the Trooping of the Color, “No other parade…more successfully combines splendour, precision, and fine music than that with which Britain hails her sovereign once a year…. London loves her pageantry and has ever been ready to welcome the world and share with all people those things which most delight us.”Footnote 11 Here, and daily at the Horse Guards on Whitehall, or at the royal palaces, the Guards could be seen—“an integral and colourful part of the London scene,” in Harold Hutchinson's words.Footnote 12

As guidebooks offered the tourist codified itineraries enabling them to move easily around the metropolis while all the time absorbing the lessons to be read off the cityscape, they thus made these sites key stops. Here, guidebooks suggested, London could become knowable. Morton directed readers to the “guard changing in the forecourt of Buckingham Palace,” and to Whitehall, where “the two mounted troopers…are one of [London's] best known sights.”Footnote 13

Both the actuality of this pageant and its insistent textual reproduction suggest a potent psychic investment in the Brigade of Guards, their integral role in imagining a particular form of Britishness. The massed ranks on the Horse Guards Parade invoked enduring military and monarchical continuities, a comforting source of national strength, stability, and pride. Moreover, as Morton's invocation of the “lifeguardsman” suggests, this investment distilled from these seried depersonalized figures onto the very tangible body of the individual guardsman. Ward Lock's Pictorial and Descriptive Guide (1933) thus looked to the horse guards: “sentinelled by gigantic LifeGuards, whose appearance is calculated to excite awe and admiration in all beholders.” They quoted, approvingly, W. E. Henley's “lines on the lifeguardsman”:

He wears his inches weightily, as he wears

His old work armour; and with his port and pride,

His sturdy grave and enormous airs,

He towers, in speech his Colonel countrified,

A triumph, waxing statelier year by year,

Of British blood and bone and beef and beer.Footnote 14

Lock and Henley alike focused upon surface. The repetitive language of physicality and strength—“gigantic,” “sturdy,” “towering,” “enormous”—constituted a very real, and very masculine, embodiment of Britishness. This was a “triumphant” body born of nationally specific conditions, its “appearance” invested with a symbolic meaning belying these descriptions' apparent superficiality. Just as “British blood and bone” invoked the physiological heritage of a superior race, so “British…beef and beer” located that superiority within a wider cultural heritage. Through birth and the sustenance of his nation, the guardsman became the unproblematic quintessence of what was manly and good. His disciplined, immovable, and awe-inspiring body symbolized Britain's longevity, power, and status to all that witnessed it.

Yet the Guards were far more than a colorful spectacle. Major-General Sir Richard Howard-Vyse's foreword to Legge-Bourke's Queen's Guards carefully emphasized how “the performers in these impressive scenes are no wooden soldiers, whose only duties are ceremonial. Every one of them is trained also as a fighting soldier, in which respect their efficiency is unquestioned. From the date of its birth, each unit has, in every war in which it has taken part, embellished…its reputation.”Footnote 15 In positioning the guards as icons of martial manhood, Howard-Vyse looked both into the past and to the future. Legge-Bourke himself described a “fighting” tradition, “increased and sanctified with the blood of tens of thousands of Guardsmen who have fallen in almost every major campaign…since 1666.”Footnote 16

Legge-Bourke again directed attention toward the bodies that individuated these traditions. The “blood” that “sanctified” their history meant that the guardsman embodied glorious heroism and strength, past and present, exhibiting that masculine fortitude upon which Britain's imperial power rested. The selfless individual body stood as a proxy for the nation, representing all that was good in British manhood. In making the ultimate sacrifice of life, limb, or blood, that individual body guaranteed the security of the social body at large, enabling it to grow ever more strong.Footnote 17 Casualty lists and medal counts alike instantiated the guardsman's “loyalty to and protection of the Crown…[his] superlative courage and devotion to duty.” These were “exacting demands, requiring superb discipline and esprit de corps,” and the Guards “deserve our greatest praise.”Footnote 18

The guardsman's role at the symbolic heart of nation and empire thus inscribed this celebratory “praise” into the everyday landscape, a constant reminder of how Britain's place in the world depended upon the flower of her manhood. Londoners and visitors found further reminders of these connections in the city's monumental topography and through the cultural landscape of popular masculinity. Ward Lock directed attention to the Horse Guards Parade, to the “Guards Division Memorial, unveiled…in memory of the 14,000 Guardsmen who laid down their lives during the Great War: ‘Never have soldiers more nobly done their duty.’ ”Footnote 19 Moreover, the guardsman's exploits were consumed avidly through the press and through stories such as Edward Ratcliffe Evans's Troopers of the King, published by the School and Adventure Library in 1933. Here was an iconic figure within a very Boy's Own tradition.Footnote 20

When the Illustrated Police News reported the “moving scenes” as the Second Coldstream Guards left Wellington Barracks for China in 1927, they thus evoked these intersecting traditions and their popular resonance: “Thousands of people thronged Birdcage Walk, and on the barrack square were hundreds of relatives and friends. Lt. Col. Lawrence…gave the order for the battalion to move off. The bands struck up a tune which stirred the blood, and with swinging strides the men marched way. The cheers from the crowds were deafening.”Footnote 21

These “thousands” came to watch and celebrate a spectacular confirmation of Britishness. Through the battalion's vigorous footsteps and passage via train from Waterloo, embarkation at Southampton, and move onward to China, they witnessed symbolic trajectories that directly linked glittering ceremonial with Britain's imperial power and role for good in the world. From the color and pomp of the barrack square to the streets of Shanghai, they could be left in no doubt as to their nation's might, an affirmation evident in their “deafening” cheers.

Homosex, Masculinity, and the Guards

The soldier hero, however, was also a rent boy. Moving among the crowds at Hyde Park Corner, Herbert W., a guardsman, approached Mr. L. After asking “would you like a nice man?” and naming his price—“7/6 or 5/6”—they entered the park.Footnote 22 This interaction was replicated at countless sites across London: in the public spaces around Knightsbridge Barracks—Marble Arch and Hyde Park,Footnote 23 on the terrace below the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square,Footnote 24 on Waterloo Road, and around Victoria.Footnote 25 Here, and at commercial venues in Soho, the Strand, Edgware Road, and Knightsbridge, guardsmen were to be found, seeking—and being sought by—older wealthier men.Footnote 26

The desires that drew the guardsman to these sites and his interactions with queer men were, however, more complex than the label “rent boy” suggests. In part, the organization of the guardsman-queer encounter as a commercial, casual, and often anonymous sexual transaction represented a contingent response to social inequality and low wages—the dominant paradigm through which it was represented. “A mercenary motive,” noted Xavier Mayne in 1908, “is…most common.”Footnote 27 Yet to foreground this commercial basis is both misleading and unproductive, for this was, in one sense, paradoxical. While cash or gifts could be accepted from middle-class men, taking money or drinks from other guardsmen undermined masculine status.Footnote 28 This paradox highlights the limitations of analytic categories of “prostitution” in understanding these encounters, suggesting the need to move beyond seeing homosex as an instrumental response to poverty, to explore understandings of sex and masculinity within the Brigade.Footnote 29

That this is the case is evident from the very different forms such encounters could assume. In 1960, one lance-sergeant recalled, “Some of us get quite fond of the blokes we see regularly…they’re nice fellows…and interesting to listen to. As for the sex…some of the younger ones aren't bad looking…. I've had some real thrills off them.”Footnote 30 This guardsman talked not about commercial reward, though he was certainly receiving money from his “bloke” and appreciated the opportunity to access otherwise unavailable consumerist pleasures. Rather, the language is of emotional intimacy—of “fondness” and mutual “interest”—and of sexual desire and “thrills.” John Lehmann similarly described his “friendship” with Jim, who “treat[ed] my flat as another home and relaxed happily on the sofa.” Jim wrote to Lehmann just after he had married and ended their relationship: “I wish I was still seeing you Jack as you were the best friend I ever had…you were always such a good friend to me…we had good times together Jack and I hope I shall see you some time.”Footnote 31 Here casual sex shaded into an ongoing and intimate relationship.Footnote 32

In the period before marriage, many guardsmen thus entered into diverse relationships with queer men, often at the same time as they had steady girlfriends.Footnote 33 Such patterns suggest that homosex and male intimacy were accepted aspects of masculine sexual “normality,” that, in George Chauncey's terms, “male identities and reputations did not depend on a sexuality defined by the anatomical sex of their sexual partners.”Footnote 34 Rather, identities were constituted through the guardsman's gendered character—his relational status as physically tough, manly, and dominant.Footnote 35 This notion of the male body as a site of domination and interiority meant that men could enact their masculinity against female and male sexual partners, through casual encounters and ongoing relationships.

The dominant scripts through which guardsmen represented their sexual encounters embodied these understandings of masculinity, for—notionally—these encounters were constrained within particularly narrow limits. In oral or anal sex, guardsmen were often unwilling to be sexually passive, since that required their submission to another man, which they interpreted as effeminizing. Active and penetrative sexual practices, by contrast, embodied the domination of a lesser man that rendered the guardsman unequivocally masculine. Buggery, heard Emlyn Williams, “doesn’t have to mean you're un peu Marjorie; I know a Guardsman who's just crazy ’bout it.”Footnote 36 Yet rather than a fixed rule, this valorization of penetration was a mode of publicly and legitimately representing homosex, suggesting the importance of performativity to notions of manliness. Providing their practices did not become known among fellow soldiers—thereby compromising their masculinity—many were prepared to be more flexible. As Herbert told L., “you can bum me.”Footnote 37

The guardsman's desires for middle-class men were thus actuated and legitimated by the gendered differences between male subjects. The guardsman could engage in a casual sexual transaction or intimate relationship partly because this was a reciprocal exchange, but—more importantly—because queer men were understood and deliberately positioned as less manly. White-collar occupations were womanlike as compared with physical labor. Moreover, if the bourgeois body did not measure up to prescriptions of toughness, differences in self-presentation also seemed effeminate. Within these mentalities, homosex was not only possible but also bestowed considerable public status.Footnote 38

Paradoxically, the strongest evidence of the possibilities actuated by these mentalities rests in practices that apparently contradicted the guardsman's participation in homosex and intimate relationships, for many soldiers interacted very differently with the men they met. Utilizing knowledge of London's queer geography and of their own sexual desirability, they picked up men whom they later robbed, assaulted, or blackmailed—often after sex or within an ongoing relationship.Footnote 39

In part, blackmail and robbery were alternative responses to poverty, allowing guardsmen to negotiate the trade's inherent inequalities and extract more from the transaction. At the same time, these were critical operations in enacting masculinity against other men. In 1929, the guardsman Roland B. met an American schoolteacher. He later told a friend he was “broke…but I won't be…tomorrow morning. I met an American…. He's rolling in money and I've got to meet him at…his flat…. When I get the money off the mug I intend going home.”Footnote 40 Entering the flat, Roland beat the man “into insensibility,” leaving with money, jewelry, and clothing.Footnote 41 He went to the Hyde Park Corner coffee stall, treating other guardsmen to drinks and boasting of having “done a mug.” In lingering detail he described the source of his wealth. “I bumped a chap…for it…when I hit him I didn't lay him out the first time…as he looked like kicking up a noise I had to hit him a few times more. I just about half-killed him.”Footnote 42 The violent enactment and public reenactment of his domination embodied Roland as an unequivocally masculine subject.

In sliding between intimate friendship and brutal assault, this taxonomy of the guardsman-queer encounter transcends contemporary understandings of homosexuality or homophobia. It is not enough to attribute these patterns to differences between individual men, to develop a psychoanalytic model of repression and denial, or to focus—as did Weeks—upon the guardsman's narrowly sexual practices, thereby silencing uncomfortable evidence of other interactions. Intimacy, sex, blackmail, theft, and assault constituted a continuum within the same cultural terrain, all underpinned by dominant understandings of masculinity. Within this social formation, sex or intimacy, as much as verbal abuse or assault, confirmed understandings of the male body as a site of interiority.

These elisions were crystallized through the public languages within which guardsmen inscribed the queer—and their encounters with him. Within oppositional constructions of male-female alterity, the queer's transgression of masculine forms hegemonic within the Brigade was easily reduced under the stigmatic category of “effeminacy.” “Pouf,” “nancy-boy,” or “twank” positioned the queer as a lesser woman-like man. Through a second order of terms, guardsmen inscribed themselves within the valorized qualities of domination. Queers were “mugs,” “steamers,” or “twisters,” terms that usually denoted the hapless victim of crime but here implied the simplicity allowing a strong man to exploit a weaker victim.Footnote 43 Persistently reiterated, whether in direct verbal abuse or in barrack-room conversation, these pejorative labels constituted a male subject against the emasculated body of the queer, defining the boundaries between self and other around a particular embodiment of masculinity. As Judith Butler's reading of “queer” itself suggests, such iterations, “operate…as [a] linguistic practice whose purpose has been the shaming of the subject it names, or, rather, the producing of a subject through that shaming interpellation…. This is an invocation by which a social bond among homophobic communities is formed.”Footnote 44

Butler's conceptualization of language's productive power is convincing. Yet her reading of the effects of this operation is overly narrow, particularly in the historically and culturally blind category of “homophobia.” That is, while the deployment of these terms functioned to establish “social bonds” between guardsmen, it also enabled encounters with that “shamed” object that transcended that category. The oppositional positioning of guardsman and queer as different structured all their divergent encounters. Imagining the queer as effeminate thus simultaneously actuated the desire for homosex and emotional intimacy—providing a way of publicly and legitimately representing those desires—the body of the queer. Significantly, assault, blackmail, and pickups were inscribed within the same terms. “Catching a mug” denoted complex cultural possibilities, consistently positioned within the gendered relationship between guardsman and queer. The line between emotional friendship, casual fuck, and predatory assault was never clear, and the queer was both desired and disparaged.

When men joined Guards regiments, they thus entered into this imaginary landscape of manliness. Cecil E. enlisted in the Welsh Guards in the 1920s. He quickly found that the interactions between guardsman and queer were “talked of in the barrack room,” embedded into everyday experience. Immersed in this milieu, Cecil was socialized into dominant forms of masculinity and sexual and cultural practice. Shortly after enlisting “another Guardsman took him to London and introduced him to some people he called ‘soldier's friends.’ ” Cecil learned of the possibilities of homosex, blackmail and theft, the sexual, social, and commercial pleasures, and masculine status that they offered. Introduced to the sites where those opportunities could be found, he began to frequent Hyde Park regularly, often with other guardsmen, looking for queers. He received guidance in the conventions that should structure his interactions with these men: what he should—and should not—do, and where and how he should do it. There was, he learned, an informal “list of charges for the various grades of offence”—seven shillings for a casual encounter. Throughout, his investment in these practices was complex. He formed a relationship with a clerk that lasted for two years, ending when Cecil blackmailed his partner, seeking the money to buy himself out.Footnote 45 The older soldiers who “taught him these practices” thus represented accumulated experience and knowledge, permeating the regiment through these ad hoc networks of connection. Constantly reproduced diachronically and synchronically in this way, the precise terms of the guardsman-queer encounter were both institutionalized and highly regulated.Footnote 46

These encounters were thus not isolated, marginal, or secretive, but a widely experienced aspect of everyday life. The frequency with which they appeared in the press was only one indication of this. Even if those cases that entered the official gaze represented only the tip of this iceberg, the statistics are suggestive. In the 1920s, around twenty-two legal offenses came to the notice of the military authorities each year. Similarly, of 127 prosecutions for “importuning” within the Metropolitan Police District in the year preceding May 1931, seven involved serving or former guardsmen. In the same period, fifty men had been dismissed “for suspicion of having been concerned in these offences.”Footnote 47 In Weeks's analysis, working-class understandings of masculinity meant that, “unlike female prostitution, no subculture developed among male prostitutes.” Footnote 48 Yet in searching for a “subculture” organized around the primary identity category of “prostitution,” Weeks remains profoundly insensitive to the historically specific organization of homosex and to the social institutionalization of the patterns he explores. The complex interactions he subsumes into “prostitution” were embedded into the everyday “subculture” of the Brigade of Guards.

A Bit of Scarlet

Those masculine qualities that figured the guardsman as a soldier hero also placed him at the very center of the queer erotic imagination, invested with very different resonance. As the War Office recognized, “persons afflicted with homosexual tendencies are strongly attracted towards soldiers…particularly [those] of the physical requirements and standards of deportment required by the Guards.”Footnote 49 The “physical requirements” demanded of recruits simultaneously rendered them an aspired-to ideal and an object of sexual desire. This was a body that many men and boys could want to have, and many others could simply want. Between the wars, and again in the 1950s, when muscular physicality was constructed as the defining aesthetic of male beauty, the guardsman was embodied as the eroticized masculine ideal.Footnote 50

This was evoked vividly in John Lehmann's barely fictionalized autobiography, In the Purely Pagan Sense. Lehmann's narrative plays out his erotic fascination with the Guards, following Jack Marlowe's meandering “safari” around London. As Marlowe encounters guardsmen, his gaze inevitably and immediately fixates upon the bodily signs of toughness. Entering a “pub near Victoria,” he meets Bill, “beautifully built with full thighs, a strongly-developed torso and hairless skin.” In an Edgware Road pub, he “gravitate[s] to[ward] one exceptionally tall and sturdily built young soldier.” Marlowe's guardsmen are always “tall and dark,” “strongly built” with “beautifully developed torso[s] and large biceps”; they “[bear themselves] in a very soldierly way with a straight back and purposeful walk.”Footnote 51

Lehmann's embodiment of male beauty was refracted through the guardsman's uniform, an erotic investment emblematized by the phrase “a bit of scarlet.”Footnote 52 If uniforms fulfilled a disciplinary function, underpinning an ethos of unit commonality, they also held wider significance within the imagined landscape of British masculinities. On Whitehall, scarlet jackets drew the public gaze to that which instantiated the guardsman's status as soldier hero, actively mediating the consumption of the male body. “Uniforms,” suggests Joanna Bourke, “enhanced men's masculine appearance: a well-designed head-dress made them look taller, stripes on trousers gave the illusion of length in stocky legs, epaulets exaggerated the width of shoulders.”Footnote 53 Imposing masculinity was deliberately constructed, affirming the guardsman's symbolic significance. The uniform, moreover, confirmed the soldier's own sense of manliness. First donning his “scarlet and gold” in 1936, Alan Roland's “breath caught in my throat…. I swore to outdo Errol Flynn.”Footnote 54

In evoking masculine physicality, uniforms were thus imagined as a material sign of erotic status, treated with near-fetishistic reverence. The Household Cavalry's white breeches, like the Foot Guards' jackets, drew attention to the “thighs” and “torsos” on which Lehmann lingered. These were, thought Ackerley, “uniforms of the most conspicuous and provocative designs.”Footnote 55 On London's streets, Roland's opinion soon changed: “I hated my uniform…it made me…a vivid, scarlet target to be stared at…visitors…stared rudely. It mattered not that the stare was often one of admiration. It made me a target among women.…And it branded me as fair game to be pursued by the vile.”Footnote 56His visibility evoked responses very different from those envisioned by state ceremonial: “grotesque” “perverts” were “attracted to young Guardsmen in uniform like moths to a candle-flame.”Footnote 57 Just as the guardsman's ceremonial body was a striking feature of the everyday landscape, so it became an arresting erotic spectacle, to be consumed and sought out in London's queer underworld. On duty, socializing, or looking for a pickup, the guardsman would always attract attention. Spatially and symbolically, this was a Jekyll and Hyde figure, oscillating between soldier hero and rent boy so that the boundaries between hero worship and sexual desire were never clear or absolute.

This instability was evoked through the private photographs taken by the architect Montague Glover between the wars. Many of Glover's photographs, particularly of soldiers on duty, could come from any guidebook. Yet their interest in their subjects is undeniably erotic. Entering Wellington Barracks, Glover photographed guardsmen in dress uniform or shirtsleeves. Always taken from below, the camera angled upward; the effect is to give renewed emphasis to the body's physicality—to sheer size, and to the muscular strength of the chest, thighs, and arms. The guardsman is not simply imposing; he is made so, as Glover literally looks up to this icon. Moreover, Glover's “props box” contained a guard's tunic, in which he dressed and photographed the men he brought home. Like Lehmann's vivid descriptions, these images are not simply a transparent window into the past, a momentary glimpse of ideals of desirability. Certainly, Glover is informed by, and mediates, a particular imagination, but his deliberate techniques and “props box” suggest that they are much more than this. Glover's photographs are active texts in constituting this landscape of fantasy and desire. Reworking hegemonic notions of male beauty, they stand as an exercise in the figurative and visual embodiment of the guardsman as eroticized masculine ideal.Footnote 58

Yet the body was not eroticized in itself, but for the broader masculine qualities it seemed to represent. That toughness invested in the working-class body denoted a “real man,” rendered closer to nature by his class.Footnote 59 Imagined as more instinctive and spontaneous than the middle class, the guardsman became infinitely more desirable. Moving with apparent ease between male and female partners reinforced these constructions. Lehmann thought his partners “entirely without moral qualms…behav[ing] as if what we did was the most natural and agreeable thing in the world. This did me the world of good.” These “therapeutic” relationships were explicitly contrasted to the constraints and guilt of his own milieu, to an experienced sense of bourgeois self-loathing: “the straightforward pagan coarseness of these boys was a constant delight to me, a contact with earthiness which I needed very badly.”Footnote 60 The language is of freedom, of simplicity: that the working-class body, by dint of its very physicality, approached some kind of “reality” from which middle-class masculinities had become distanced.Footnote 61

This distance, articulated as the encounter with a social other, generated a powerful sexual charge. Again, rather than being erased by sexual desire, class difference actuated that desire, eroticized in almost gendered terms.Footnote 62 Of Tony Hyndman, Stephen Spender commented, “The differences of class…between [us]…provide[d] some element of mystery, which corresponded to a difference of sex. I was in love…with his background, his soldiering, his working-class home.”Footnote 63 Spender loved the alterity Hyndman represented, as much as who he was. His “difference of sex” meshed with a wider distinction between “queers” and “men,” embedded in class differences. If the queer was exclusively interested in men and as middle class, comparatively feminine, the working-class “man” was unambiguously masculine and “normal,” albeit willing to engage in homosex.Footnote 64 This encounter between different and unequal male bodies, the thrill of social transgression, was a defining aspect of the guardsman's desirability.Footnote 65

Knowledge of this fantasy, and the guardsman's sexual practices, brought any contact between serviceman and civilian under critical scrutiny. This kind of interclass homosociality seemed neither proper, nor—under normal circumstances—possible. When, in 1926, the decorative artist Frank W. was arrested on the Strand, Detective Slyfield carefully informed the Bow Street magistrate that, “on [his] possession…[were]…several addresses of soldiers.” These addresses, Slyfield suggested, evinced an interest that could only be erotic, invested with sufficient suspicion as to substantiate the charge of importuning.Footnote 66 In court, these written fragments thus generated a conflict over the legitimacy of social mixing, as men sought to present their interest in the guards as innocent, rather than immoral, altruistic, rather than erotic.

These strategies were evident throughout the 1936 inquest into Reginald J.'s suicide in Colonel C.'s Golden Square flat. Reginald had been discharged from the Grenadier Guards after their “association” in Cairo. That they had continued to meet in London aroused the coroner's suspicion: “Why did you associate with a private, not casually but in your own flat?…I do not understand how any decent officer should associate with a private unless the relationship were improper.” C. presented their relationship as justifiably philanthropic: he had given Reginald money since he was “hard-up.” But he could not explain why Reginald's visits had made him “nervous”: “ ‘If your relationship were perfectly proper and innocent, why were you nervous that he might blackmail you?’—‘Because I realised he might say something extremely unpleasant as it was not a moral thing to do to speak to a soldier private.’ ” Tacitly acknowledging that social mixing was “not a moral thing,” just as he sought to give it an unequivocally “moral” foundation, the colonel's denials underscored the public anxieties generated by knowledge of the eroticized guardsman.Footnote 67

Yet the colonel's fears suggest the private ambiguity of this fantasy, that is, that the guardsman's status was never unproblematic. In part, this followed from knowledge of his “tendency…to robbery…violence” or blackmail.Footnote 68 As the discussion above suggests, the toughness structuring the guardsman's sexual practices could underpin very different encounters. The muscularity that rendered the guardsman so attractive also made him a physical threat, his desirability tainted with unease and fear. Lehmann's description of Bill moved to note how “under [his] charm and good manners lurked always a hint of danger and violence.”Footnote 69

Such fears recognized the contradictory masculinities brought together in the queer-guardsman encounter, contradictions that could disrupt the guardsman's idealized status. If the commercial organization of his sexual practices made the guardsman accessible, that ideal further evaporated through the experienced social differences within which that exchange was embedded. That the guardsman was “venal,” or “mercenary,” somehow undermined the morality of his appeal.Footnote 70

In part, the enduring relationships they often forged deflected men's nagging fear that this was simply “prostitution.” Soldiers, noted Lehmann, “were really anxious for friendship…. They wanted a protector who would provide a sexual outlet of…a completely innocent sort…supplement their miserable pay, and spoil them a little with good food and drink…and…[those]…semi-luxuries, which they coveted but could not afford…[this was] a warm fatherly or elder-brotherly relationship.”Footnote 71 Displacing these anxieties into an idealized “friendship” that enshrined the queer's status preserved the moral integrity of Lehmann's fantasy.

Yet the emphasis upon a particular power dynamic rendered this ideal inherently unstable. In the 1950s, Lehmann encountered a “wave” of “military prostitution” in which “the troopers were having a succeàs fou.” “Their popularity had gone to their heads…. Some…were making…£40 or £50 a week…servicing a list of older admirers.” The result was “comic”: the “unostentatious” queer witnessing guardsmen drinking “double brandies, arrayed in the latest fancy waistcoats and expensive suede shoes.” The “astonished” Lehmann soon “discovered…a deep-seated objection in…being just one of the dates on their nightly list.”Footnote 72 In acquiring the trappings of consumerism—“fancy waistcoats”—the guardsman lost that unequivocal working-class status his uniform symbolized and Lehmann fetishized. When “callous” and “mercenary” motives became evident, his idealized friendship became polluted and untenable. Sensing that he was being exploited, Lehmann reacted angrily. If social difference opened up a realm of sexual and social pleasure for him, guardsmen should not be able to opt simply for the former—they should be his friend. The “fatherly” relationship was intrinsically possessive. The queer's wealth and status was supposed to give him the upper hand.

It was upon this notion of proprietorship that class antagonisms coalesced and the fantasy of the guardsman collapsed. Middle-class expectations of intimacy, particularly their role as provider or “husband,” contradicted dominant scripts of manliness within the Guards. Toughness was a refusal to be subordinated to any man. That being “kept” could be experienced as effeminizing and emasculating was evident in Hyndman and Spender's relationship, once living together from 1933. Although they tried to negotiate these contradictions—Hyndman was ostensibly Spender's “secretary”—their relationship ended in 1935. Hyndman believed Spender “began to be jealous as I made friends on my own…. He…felt that I only ought to know [other people] through him…. He wanted to own me. I was to be…his wife…his, altogether…. It was jealousy of me being someone in my own right.…It's against my dignity.”Footnote 73

If the guardsman was eroticized as unequivocally male, that very manliness disrupted the relationship the queer expected, just as it initially fueled his desires. Spender wanted his “man” also to be a wife, a role Hyndman could not and would not perform.

If the problem of “ownership” cohered around inequalities of wealth, social difference produced further cultural antagonisms. Their different backgrounds pushed the guardsman and queer apart, just as they came together. Ackerley's partners were never simply an erotic ideal, but “dumb pumphandlers,” “the most inefficient prostitutes any wretched man had to fall back on.” In his circles, the guardsman could find himself socially isolated, disparaged as inferior.Footnote 74 This hostility went further. Ackerley thought Freddie Doyle's quiffed hair “a typical example of working-class vanity and ineptitude and propriety.” He continued, “how irritating and unsatisfactory the…working classes are…with their irrationalities and superstitions and opinionatedness and stubbornness…and laziness and selfishness.” These were “ignorant people who think they know everything.”Footnote 75

Yet if social difference could be a barrier to enduring relationships, the alternative was equally unattractive. Socialized into middle-class ways of being, the guardsman became far less desirable. Giles Romilly, for example, railed against how Spender “wasn't capable of appreciating” Hyndman's spontaneity: “he was always trying to improve [him].” By seeking to narrow their social divide, “educating” and “civilising” Hyndman, he had removed that which “attracted him in the first place.” When Hyndman reverted to his “old self,” however, leaving Spender for the International Brigade, Gavin remained uneasy. Hyndman was “hearty, aggressive, coarse, damn everybody, fuck the world as if he had never been the essentially gentle, warm, cosy intimate person we had come to know.” He was “awful,” lost “in this conglomerate of tough and sweaty maleness.”Footnote 76 In the guardsman-queer encounter, their very alterity could be irreconcilable.

Simultaneously, therefore, the idealized guardsman collapsed into a disparaged other, the two existing in persistent tension. The desire for sex and intimacy made this an unrealizable fantasy. When the ideal “friend” proved unobtainable, all that was left was the guardsman's apparent “venality.” Objectified easily, his body could be imagined as a commodity to be bought, possessed, or “given,” and Ackerley could regard Doyle as, “after cigarettes, a thing I must cut down or…altogether abolish.”Footnote 77 Rendered passive and quiescent, the guardsman, notionally, existed for the queer's pleasure. He was, noted Michael Davidson—using the slang that so evokes this arrogance—“to be had.”Footnote 78

Corruption

Given the psychic investment in the guardsman as a proxy for the British nation and manhood, the evidence of his sexual practices that erupted into public view regularly was profoundly disquieting. As Dawson suggests, while the guardsman's status was enshrined in the pageantry of state ceremonial, “other subversive or non-functional [masculine] forms (notably the effeminate man or the homosexual)…met with disapprobation and repression in explicitly national terms.”Footnote 79 The guardsman-queer encounter brought together positive and negative poles in a supposedly unambiguous hierarchy of national masculinities.

After the revelations of homosex generated during Cecil E.'s 1931 trial, Ernest Wild, the recorder, asked Inspector Sharpe, anxiously, “if Guardsmen lent themselves to this sort of thing?” “I am afraid they do…there is an atmosphere of this kind permeating a section of the Guards.”Footnote 80 Wild erupted in fury: “If…some members of the Guards wearing his majesty's uniform have degraded themselves in the royal park, it is an appalling state of things…it behooves not only the regiment but the police to root out this vice. If it is allowed to become rampant, it may cause the fall of this city and country.”Footnote 81

Wild's outburst constituted a very tangible sign of the fears generated when the soldier hero encountered his negation—when the guardsman became a rent boy. This “appalling state of things” threatened to overwhelm the nation. Wild's focus on seemingly innocuous codes of dress instantiated those anxieties underpinning his anger, for it was the guardsman's uniform that symbolized his iconic masculine status and the national traditions that embodied. To engage in homosex while wearing “his majesty's uniform” was to degrade the individual, his regiment, and Britain itself. It was to erode the masculine qualities upon which Britain's strength depended. The stakes were high, for if this “vice” were not “rooted out,” it could spread contagion-like and “cause the fall of this city and country.”

Facing these anxieties, many commentators simply denied the actuality of the guardsman's practices. His iconic status made it inconceivable that the soldier hero could have homosex. In 1929 the journal John Bull attacked press exposès of a “gang” of guardsmen engaging in blackmail—and, implicitly, homosex—in Hyde Park. The Guards had “been subjected to a shameful slander in circumstances which allow them no means of retaliating. So scurrilous have been the slurs…that they have been linked with blackmailers and terrorists…we deem it our duty to take up the cudgels on their behalf.” For the Brigade and the nation, John Bull embarked on a quest for truth, posing as the guards' public voice to attack “unjustified” reportage in which facts were “distorted” in “the craze for sensationalism.” Contrasted to the feminine hysteria of “sensationalism,” they brought masculine rationality to bear. Careful “investigations” demonstrated “quite definitely that there is no such gang.” John Bull had been “assured by high guards officers that drastic steps are contemplated to vindicate the honour of these famous regiments.” These “drastic steps” were not a matter of investigation but envisaged simply as maintaining the soldier hero's untainted image.Footnote 82 To protect the Brigade's reputation, John Bull and “guards officers” reiterated it.

Ultimately, however, it was undeniable: guardsmen did have sex with men. Further, as the War Office noted in 1955, this was a peculiarly metropolitan issue: “In London homosexuality is undoubtedly much more prevalent than elsewhere.” While owing to “its essentially secretive nature,” the “problem cannot be well expressed in statistics,” the War Office deemed it “relevant to note that, during 1954, the Royal Military Police investigated 28 cases of sodomy and gross indecency in London…compared with one case in…Western Command and five in Scotland.”Footnote 83

Such patterns made London the spatial and symbolic focus for the guardsman-queer encounter, ensuring that the modern city exercised a powerful influence over the ways that encounter was discursively produced. In London, where the guardsman's ceremonial and sexed body was simultaneously most evident, civil and military authorities were forced into an uncomfortable engagement with his dissonant status as soldier hero and rent boy. How could the embodiment of British manhood participate in homosex? How could this threat to the nation's social body be accommodated? How could hegemonic masculinities be protected? As they negotiated these disquieting questions, the pleasures and dangers of the modern metropolis loomed large. In striving to maintain the guardsman's status as soldier hero, his sexed body was inscribed within a contradictory set of silences and evasions. Never denying the actuality of these encounters, defensive dominant narratives constructed the guardsman as an innocent abroad in the city, vulnerable to the temptations placed before him. Placed within wider axes of social power, constituted at the interstices of class and age, the guardsman's sexual practices were justified and exculpated, and his masculine status secured, at the cost of rendering it inherently unstable. The War Office thus outlined how

the contamination of members of the armed forces stationed in London is a greater risk than that incurred in the provinces…there is in addition to [the guardsman's] separation from his family…an environment containing all shades of entertainment…at a very high cost. It is thus possible for him to be perpetually short of money…amidst attractions where complete supervision is impossible…soldiers have obviously succumbed to a temptation for easy money…. [V]ice and target exist together in concentrated areas and circumstances which favour the practice of the former and render the latter more vulnerable.Footnote 84

Contrasting sexual threat—the older, wealthy queer—with sexual vulnerability—the young guardsman—the War Office constituted the Guards as virtuous normal men exploited by vicious queers. This narrative of sexual danger interwove anxieties over class and generational difference into a broad critique of the city's effect on working-class men. In London the glittering temptations of the consumerist metropolis intersected with the realities of inequality. Transgressive sexual practices were a function of the guardsman's subordinate position within differentials of wealth, age, and status, his “vulnerability” to the suggestions of others. Within this volatile matrix, the queer became a near-apocalyptic threat and London a disruptive space of immorality and danger.Footnote 85

The commercial organization of homosex thus constituted consumerist temptations as the defining feature of this vulnerability. In 1951 Robert B., a British Broadcasting Corporation official, was arrested with several lifeguards in his Curzon Street flat. Robert had first met Corporal S. at a party in 1948. In 1950 Robert approached S. for, “some company.” S. took troopers to parties at Robert's flat, receiving almost £300 for “himself and the boys.” Corporal W. had “been to the flat dozens of times with other troopers…after we had something to eat and drink we would leave B. with a trooper. Besides buying us clothes, cigarettes, and drinks he would nearly always fork out a fiver.”Footnote 86

Newspaper reports highlighted the draw of the metropolis and persistent social inequalities, eliding sexual threat with social difference, consumerist temptations, and the dangers of seeking a lifestyle above one's status. Lifeguards at Mayfair cocktail parties symbolized these risks, the disjunction between appropriate and inappropriate consumption mapped onto the slide from virtue into vice: “these soldiers would normally be drinking beer, but had been out in London drinking port, champagne, and brandy.”Footnote 87

Rather than vicious and depraved, in such narratives, the guardsman became an innocent victim. This was a comforting fiction, persistently reproduced for public consumption. The guardsman did not participate in homosex because he wanted to, but for money and the pleasures it could buy—his subordinate position seemingly precluding his capacity for moral agency. Simultaneously emphasizing commercial transactions, and dissonances of age and wealth, while remaining notably silent about the guardsman's agent role and desires, and the ways that such practices were embedded into everyday life, rendered the guardsman-queer encounter an imagined instance of corruption. “Young soldiers”—they were always “young soldiers”—were “perverted”; they were “led away by older men,” or “contaminated,” or “tempted to lend themselves to these practices for money.”Footnote 88 Such language instated power as the central trope through which the state and the press negotiated the anxieties generated by these encounters. The notion of corruption pivoted upon a specific geography of power, morality, and guilt—the contradistinction between the predatory queer and his otherwise normal victim. When “men of means and…position pay younger men of a different class to gratify them,” argued Lord Chief Justice Goddard, “it is the former who are the worst and…greater danger.”Footnote 89

These differential notions of guilt were reflected in sentencing policies that defined the queer as a potent threat to British manhood while suggesting the guardsman's essential innocence. Robert B. received eighteen months of imprisonment after the Curzon Street trial. George B., the trooper involved, was bound over for two years.Footnote 90 Here, as for other crimes for which guardsmen were tried, this sympathy was reinforced by recognition of their brigade's reputation and individual service records—their status as soldier heroes. Within this imaginary landscape, magistrates were strikingly reluctant to impose the law's full punishment. Footnote 91

These patterns embodied the confidence that guardsmen's actions were temporary aberrations, that they were normal men who could be redeemed as masculine citizens. Regiments regularly retained convicted men, certain that, as one officer put it, something could be done to “restore [their] self-respect.”Footnote 92 After the Curzon Street case, the recorder addressed Robert on his “corruption of soldiers, otherwise reasonably decent young men.” While he positioned Robert within potentially sympathetic medical aetiologies of sexual difference—acknowledging his need for “psychiatric treatment”—he accepted that he endangered Britain's social body. It was “clear that you should be removed from the community.”Footnote 93

He addressed the trooper very differently. While acknowledging George's offense, in assuming that George had “been led into this,” he went some way to exonerating him of moral guilt. George should “take warning” though, lest he continue to slide into depravity. Masculinity here was not an innate given, but to be achieved through determined struggle: “If you cleanse yourself by hard work, there is no reason why you should not return to the ranks of decent honest soldiers.” Purified of the taint of homosex by the physicality of “hard work,” George could once again reenter Britain's masculine elite. The threat to the guardsman's manhood, and therefore the nation, was never irreversible.Footnote 94 So powerful were assumptions of corruption that, after Robert's imprisonment, the recorder could remark that, “the prime instigator has now been removed…it is unlikely that such conduct will happen again.”Footnote 95 With the queer “removed,” it was inconceivable that guardsmen would engage in homosex. Britain was safe.

Protecting the Innocent

As military and civil authorities and the press negotiated these anxieties, they found themselves adopting a position that was contradictory and unstable. Discourses of corruption and normality produced a comforting set of silences and evasions around the Guards' sexual practices. Yet the implications of this were disquieting. To use the terms suggested by Eve Sedgwick, corruption invoked both minoritizing and universalizing discourses: homosex was securely confined to a tightly bounded subculture, yet it threatened to spread contagion-like into the ranks of normal men.Footnote 96 If guardsmen could be corrupted, masculine normality became inherently vulnerable. Constantly imperiled, it demanded equally constant protection, and the discursive position that maintained the Guards' status simultaneously undermined it, for corruption required that the guardsman be passive, quiescent, and malleable. The assumptions about class and power within which the guardsman was marked as a victim removed that independence and strength that defined a real man, precluding any capacity for agency. To protect the symbolic integrity of the guardsman's body, the state and the press had to emasculate it.

Throughout the twentieth century, military and civil authorities thus sought to ensure that, in Legge-Bourke's words “every possible effort is made…to see that every man…is fortified in the cause of decency and responsible behaviour.”Footnote 97 In May 1931, following the furor surrounding Cecil E., the director of public prosecutions convened a conference on “homosexual offences in which soldiers…might be concerned” at the suggestion of the Adjutant-General. Attended by officers from London District Command and the Judge-General's Office, as well as representatives from the metropolitan police and the director of public prosecutions' office, the conference explored how the state could “protect the young soldier from contamination by other people.”Footnote 98

Their discussion focused upon “the possibility of creating a public opinion in regiments entirely hostile to this type of offence.” There were, as General Corkran observed, already informal—if inadequate—measures in place to do so: “the young soldier coming to London was quietly informed by…his officers as to the danger of sexual offences…[though] he did not think many…knew that soliciting was a criminal offence.” The conference approved formalizing such ad hoc individual conversations. In place of institutional silence and half-knowledge, they brought these practices into full public view, inscribing the guardsmanqueer encounter within a particular form of knowledge, invested with the full authority of the British state: “Young soldiers might be informed of their liability for these offences [through]…a lecture on homosexual offences; a warning might be given as to the sort of person who would be likely to approach them…and the ill-effects of these practices might be mentioned.”Footnote 99

Through this educational framework, guardsmen were socialized into the full requirements of an agent masculine citizenship. By describing this “sort of person,” lectures identified the queer precisely. Outlining the risks of succumbing to this threatening figure's advances in terms of the law and the “ill-effects” on the male body's health made men only too aware of what was expected. Prison, discharge, and physical ruin: this was a powerful warning of the dangers of homosex. Inculcating their responsibilities, rendering hegemonic masculinities explicit, civil and military authorities sought to ensure that the individual guardsman lived up to his imaginary status. The soldier hero—the British male—should refuse the queer's advances.Footnote 100

As the conference implicitly acknowledged, however, this responsibility could not be taken for granted. The boundaries they constructed between guardsman and queer had to be further maintained by a pervasive network of surveillance. The full panoply of disciplinary power at the state's disposal was thus brought to bear to symbolically and practically shore up hegemonic masculinities. As Corkran noted, “the Military were anxious…that action should be taken by the police…to show the country that this class of offence could not be tolerated.” While intensifying police surveillance was central to their deliberations, they also considered alternatives, rooted in their exact spatial specification of “homosexual offences.” “The particular desire of the authorities,” suggested the Adjutant-General, was “to protect the soldier from the advances of the class of men who go to Hyde Park for these practices.”Footnote 101 Returning to a debate initiated in 1903, the conference discussed placing Hyde Park “out of bounds” to soldiers. They eventually rejected this as unworkable—for reasons explored below—relying instead on the alternative disciplinary technologies of improved lighting and regular patrols by civil and military police.Footnote 102

As these debates suggest, the geographical knowledge within which London became an immoral and threatening metropolis was more finely calibrated, driven forward by accumulated policing experiences to situate sites of sexual danger precisely within the cityscape. When, in court in 1951, one man was asked, “in your five years in the Coldstream Guards did you never hear of the perils of Piccadilly?” the implication was clear: in Piccadilly the guardsman became particularly vulnerable.Footnote 103 In 1955 the War Office identified four districts “in which offences involving soldiers tend to originate:” “Chelsea, Victoria, Hyde Park, and the eastern end of Edgware Road.” They went further, specifying “the actual venue of offences:” “Parks…Stations…Public Houses and Cafes…Private Houses and flats.”Footnote 104

Mapping these “perils” identified geographical targets for official intervention, sites at which state and queer struggled for control over the guardsman's body. Like Hyde Park, or Strand pubs, queer public and commercial spaces were marked out for observation by the Met and “trained members of the S[pecial] I[nvestigation] B[ranch]” of the military police. “Undesirable premises” were “placed out of bounds”—ten pubs and cafes in 1955. This strategy sought to articulate an absolute spatial demarcation between predator and prey. If guardsmen could not be trusted to refuse the queer's advances, they were to be excluded from sites where they could face such temptations.Footnote 105

In 1955—as in 1931—the authorities recognized the limitations of “out of bounds,” tacitly acknowledging guardsmen's agent participation in homosex. “There would be a difficulty in regard to men not in uniform if a particular…place was put out of bounds,” thought Corkran: “He could deal with the man in uniform but not the plain-clothes man.”Footnote 106 By discarding the visual codes of position, soldiers could easily evade surveillance. Moreover, “out of bounds” risked becoming counterproductive, drawing attention to practices of which guardsmen could otherwise have remained ignorant. “There are,” noted the War Office, “some young soldiers who, when they see a thing is out of bounds, walk along there to see why.”Footnote 107

If the authorities remained keenly aware of the precarious nature of the order they sought to impose upon the Guards, the implications of these policies were clear. This was an attempt to inscribe these recalcitrant masculine subjects within a diffuse web of power, knowledge, and surveillance. Through education and disciplinary institutions, the guardsman's body was nominally ordered into a singular subject position, rendered knowable within the epistemological framework of the soldier hero. To use Butler's terms, these strategies sought to “materialize” the male body in very specific ways—to ensure it acted in particular ways, and with particular people.Footnote 108 Underpinning this exercise was a hegemonic conception of masculine citizenship, constituted through the notion of corruption—the rigid spatial and discursive oppositions between normal and queer, British and treacherous, moral and immoral, pure and diseased. The symbolic embodiment of the guardsman was a synchronic exercise in constituting the gendered body of the nation itself. Called into being in contradistinction to the iconic body of the soldier hero, the predatory queer established the abject outside of Britishness.Footnote 109

Yet the guardsman's body always threatened to rupture the boundaries within which it was inscribed, never simply a passive inscriptive surface to be marked through the operations of power. Implicit within all these disciplinary techniques, as Elisabeth Grosz suggests, was a body that, in its social and sexual practices, represented “an uncontrollable, unpredictable threat to a regular, systematic mode of social organization.” Official strategies thus operated at, and marked out, the point of convergence between the discursive and the material, between the Foucauldian body and the body as “internally lived, experienced and acted upon.”Footnote 110 In its very intractability, the guardsman's body ensured that hegemonic masculinities were always experienced as contested and vulnerable. Institutional processes of embodiment were ongoing and defensive, their success never complete or assured. Nevertheless, if the nation's gendered body was constantly rent and repaired, this was a process that—through its very existence—played a powerful role in constituting British masculinities.

Defending the Guilty

If the operations of institutional embodiment were contingent upon the guardsman's body as a site of agency, so, too, they were constitutive of the ways that soldiers experienced and represented their own bodies. Corruption provided a space within which guardsmen could justify their actions. Adopting the posture of innocent victim simultaneously legitimated homosex and assault, robbery, and blackmail, colluding in the authorities' attempts to deny their capacity for agency. Remaining silent about their own desires, guardsmen sought to evade the law's potential wrath. If this tactic was rarely wholly successful, because it was often undeniable that men had broken the law and should face punishment, by exploiting the anxieties explored above, they could find a tenuous sympathy in court.

The defense at Raymond M.'s blackmail trial in 1934, for example, urged the extenuating circumstances of vulnerable youth. As a nineteenyear-old guardsman, Raymond “came under the evil influence” of an “elderly” civil servant who “kept M. as his companion…for six years” before he “got tired of him and threw him over.” Having become “used to a life of luxury” beyond his means, Raymond had then struggled against London's temptations, before resorting to blackmail as the only way to maintain this lifestyle. He had “[done] his best to get work…[he] had…been subject to temptation but with the help of religion he had been able to resist it.” Since the maximum penalty for blackmail was life, his four-year sentence was light.Footnote 111

Raymond's defense recognized that he had transgressed expected social roles, while effacing the desires allowing him to remain with this man for six years. Yet the posture of innocent was more commonly employed against charges of assault, where strategic victimhood meshed easily with guardsmen's understandings of aggressive manliness. That violence was understood as a natural response to the outrage engendered by queer advances was suggested in Bernard S.'s remarkable defense against blackmail charges. After meeting on Piccadilly, Bernard had returned to Mr. A.'s flat. He denied that this was premeditated: they had met “quite by chance.” Apparently oblivious of lectures on spotting the queer, he “did not recognise him as the type of man he was.” His counsel admitted Bernard had acted wrongly: “In every city there are men who crawl about like Mr A.,…but you cannot have people demanding money from them.” “What S. should have done,” he continued, “was to have knocked down this man, or reported him to the police.” Placed above legal redress, physical assault was envisaged as self-defense—inevitable and legitimate.Footnote 112

The contradictions of innocent victimhood were highlighted in Roland B.'s 1929 trial for robbery with violence. Roland pleaded “justification of the attack.” Walking along Piccadilly, he had “passed…Mr. E. ‘He looked very hard at me…I thought he knew me. I stopped and looked round.’ ” The man came back, inviting Roland for a drink at his flat. There “having been plied with whisky, overtures were made which ‘sent him mad.’ ” Roland was “feeling dizzy when [E.] asked me to go to the bedroom. I told him I was quite comfortable but he took my arm and led me into the room…[There he] acted in such a way that, realising his intentions and being full of whisky, [I] became mad and hardly knew what happened. I recollect hitting him…with my fist, and then hitting him again…but I cannot remember any other blows.…I took some money and other things…in repayment of what he had done to me.”Footnote 113

Roland's narrative turned upon a pivotal moment of “madness.” This was an implicit experience of dislocated selfhood, of moving beyond the limits of consciousness and control, evident in the sensate qualities of “dizziness,” and then blankness. Recognizing this sexual advance so disrupted the male body's integrity as a site of interiority as to preclude the capacity for rational action. So severe was this affront that it warranted spectacularly violent retribution. Through the faintly remembered punches and the blows with a chair leg that followed—memory of which was suppressed—Roland physically and symbolically defended his body's boundaries.

There was a dual tension here. Roland pleaded justification, yet he denied his capacity for the agency on which that depended. Despite becoming detached from reality, he was composed enough to leave with all he could carry. Scornfully, the prosecuting counsel focused upon these contradictions: “ ‘You struck Mr. E. in defence of your honour?’—‘That is right.’—‘Was it the same motive that induced you to steal his clothes, money, and jewellery?’ ‘I wanted some revenge.’—‘On that argument it would be very profitable for you if your honour was in danger every night?’ ”Footnote 114

While Roland's defense was internally problematic, he successfully displaced the court's attention from his actions onto Mr. E.'s, by suggesting that he himself was the innocent victim of a predatory advance. The cross-examination of E. sought to expose these immoral motives. Why had he gone for a late-night walk on Piccadilly? “His only object…was to take the air.” Was he “prepared to take home…the first man [he] met?” Had he done this before? He rejected this line of questioning vehemently: he had not spoken to Roland first, nor plied him with drink, nor made “a certain suggestion.”Footnote 115

Such encounters forced courts to negotiate competing claims to respectability and innocence. The guardsman's posture of outraged normality clashed with the counterclaims of those they were alleged to have attacked or had sex with. While Ernest Wild's interventions suggested suspicions over E.'s motives, he was never explicitly positioned as a predatory queer.Footnote 116 To the jury, Wild pointed out that, “if a man were ‘mug’ enough to take a stranger home…they must not say ‘serve him right.’ He might be a fool, but he need not be a bestial fool.”Footnote 117 If E.'s “bestial” nature could not be presumed, the horrific violence of Roland's assault was undeniable, and E.'s “wounds…hardly commensurate with [his] declaration” of “self-defence.” Moreover, as Wild outlined, “taking the law into one's hands was not permitted in this country…. The only vengeance which was recognised…was the vindication and enforcement of the public rights in the courts of the King.”Footnote 118 Given these circumstances, Wild could not but pass a prison sentence.

The incident, however, was sufficiently ambiguous that Roland's defense remained implicitly persuasive. Wild noted that he “had been found guilty of one of the gravest offences known to law, the maximum sentence for which was penal servitude for life and a whipping.” Despite this, he passed “the least sentence commensurate with the offence…three year's penal servitude.”Footnote 119 This, and his preceding comments, suggested the credence Roland's narrative generated. If his actions and uncertainties around E.'s “immorality” meant the contradistinction between predator and victim was never stabilized, it still exercised a defining influence over the trial. An assault on a queer man could never be accepted unequivocally, but it could be understood easily.

Nonetheless, set alongside repeated evidence of their active participation in homosex, these competing claims and the brutal reality of many encounters persistently disrupted the Guards' iconic status. At times, they seemed far from being soldier heroes, and it was impossible to see them as innocents. The contradistinction between predator and victim was profoundly unstable. In 1929, imprisoning a nineteen-year-old Grenadier Guard, Henry Dickens, the common serjeant, was thus in no doubt as to the locus of danger in the case. No longer a soldier hero, he “was a disgrace to the uniform he wore…one of those degraded fellows that were a disgrace to the country.”Footnote 120 His undeniable agency meant that this man was a dangerous source of moral evil within the Guards.

Forced back onto the comforting notion of the bad apple, the isolated and abject body, Dickens—like many other commentators—sought to deflect critical attention from the ways that these practices were embedded in everyday male life. The reality of these counterhegemonic masculinities was too disturbing to contemplate. There were, he suggested, exceptional and reprobated instances to the rule of heroic masculinity. The man who engaged in such practices was not a real guardsman. Rather, he was a dangerous other who “disgraced” his uniform, and was thereby outside the community of his unit. When a guardsman fell short of standards of “decency” commented Legge-Bourke, “the grief…is nowhere more genuine than among his comrades.”Footnote 121

Counternarratives

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the anxieties surrounding the guardsman acquired a particularly electric resonance, since the war and the social changes it unleashed problematized the critical interpretative categories—of masculinity, youth, consumerism, and nationhood—within which the guardsman's sexual practices were conceptualized. When established notions of Britishness seemed threatened from every direction, the guardsman-queer encounter became ever more dangerous, assuming a central symbolic position in the postwar politics of sexuality.

Wartime pressures placed the integrity of the gendered national body under increasing threat. Overseas service and the ever-present reality of the male head of household's death disrupted the “natural” organization of the family—concerns intensified by women's growing independence and the number of “war babies” born out of wedlock. The consolidation of the family was thus central to postwar reconstruction, exemplified by new housing provisions and the promotion of companionate marriage. Official anxieties were compounded in the late 1940s by rising divorce rates. The National Marriage Guidance Council (1948) and the Royal Commission on Marriage and Divorce (1951) were symptomatic responses to this perceived crisis. Moreover, rising rates of juvenile crime, dramatized by repeated panics surrounding metropolitan youth cultures, focused attention upon young men's socialization into normative masculinities. That youths were growing up in female-dominated households, without suitable male role models, made their future cause for massive concern.Footnote 122

The anxieties surrounding the guardsman-queer encounter were sharpened further by vociferous critiques of the transition from postwar austerity to 1950s affluence. Working-class prosperity and consumerism generated profound unease among many commentators, who were nostalgic for traditional communities. Affluence and Americanization, argued Richard Hoggart's The Uses of Literacy (1957), threatened to rob the working class of its authenticity. As the Curzon Street case suggests, these critiques resonated with the identification of consumerism as a danger to the guardsman's moral integrity. Not only did affluence taint the working class, but it also threatened to corrupt young men in a very real sense, seducing them away from normative masculinities. Echoing Hoggart, civil and military authorities wanted the guardsman to remain pure, working class, and uncorrupted by consumerist temptations. Ironically, these authorities assumed the same position as many queer men. Lehmann's attack on “fancy waistcoats” suggested that guardsmen were supposed to remain unequivocally working class.Footnote 123

Within this context, the queer became a profound source of cultural disturbance, threatening to destabilize the family and to seduce Britain's young men away from hegemonic masculinities. Proliferating reportage of intergenerational sexual encounters and the activities of groups like the National Campaign to Protect Juveniles against Male Perverts reinforced such notions, in a panic fueled by spiralling numbers of arrests for “sexual offences.” Britain's declining imperial status invested these anxieties with further resonance, disrupting long-established notions of Britishness. When the empire was fragmenting, and comfortable assumptions of the ordered social body were eroding, the guardsman-queer encounter became a symbolic trope around which these anxieties crystallized. The queer, a predatory and lustful danger to the nation and its manhood, embodied a wider postwar crisis of Britishness.Footnote 124

Responding to these fears, in 1954 the home secretary, David Maxwell-Fyfe, appointed the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution—known after its chairman, John Wolfenden. The committee, as Frank Mort suggests, constituted an exercise in “productive surveillance.” Mapping “dangerous sexualities” through the evidence generated by official bureaucracies and “expert” witnesses rendered them “visible to the official mind” as a strategy in their effective regulation. Explicitly, this was an attempt to restabilize the nation's gendered body.Footnote 125 Yet while, as this discussion suggests, notions of the guardsman's vulnerability embodied the anxieties underpinning Wolfenden, the committee and the explosive debates of the 1950s simultaneously generated the discursive and political space enabling elite queer men to challenge such assumptions. Seeking to construct a respectable, nonthreatening, and legitimate queer subject, inscribed within the private space of the home—the beneficiary of reformed sexual offenses laws—they submitted written memorandums and testified before Wolfenden; they wrote letters to the press and published sociological and autobiographical studies of queer life.