Introduction

In labour market policy, many European welfare states are experiencing different forms of reregulation. This questions the liberalisation trend that has dominated political economies in recent decades (Streeck Reference Streeck2009; Thelen Reference Thelen2014) and also sheds light on a new aspect of the dualisation debate in comparative welfare state research (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010; Schwander and Häusermann Reference Schwander and Häusermann2013). A striking example is the introduction of a statutory minimum wage in Germany in 2014 (Marx and Starke Reference Marx and Starke2017). When talking about reregulation in labour market policy, the meat-processing industry presents a least likely case, since here liberalisation has reached its peak. In the European Union, the sector is characterised by growing international interdependence and a strong export orientation as well as exploitative working conditions that contribute to the competitive advantage of the sector. In many countries, this demand for cheap labour is primarily covered by migrant workers (Afonso and Devitt Reference Afonso and Devitt2016; King and Rueda Reference King and Rueda2008). Following power resource theory (Korpi Reference Korpi1983), migrant workers are expected to have limited power resources: first, they often do not constitute a share of the electorate in their working country. Second, although they are to a certain extent represented by trade unions, the position of trade unions towards migration has historically been described as ambivalent (Afonso and Devitt Reference Afonso and Devitt2016). Third, most migrants in the meat-processing industry are agency, posted or subcontracted workers for whom trade unions have only developed organising strategies reluctantly (Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016). In the literature, these forms of nonstandard employment have been named precarious work, as they are badly paid, insecure and include bad working conditions (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015). In the case of the meat-processing industry, the categories of both migrant and precarious workers strongly overlap, which is why their situation can be considered particularly challenging. Given this unfavourable starting point, policy changes towards the improvement of working conditions in this specific sector seem highly unlikely.

Quite surprisingly, however, in recent years, the governments of countries as diverse as the United Kingdom and Germany have made considerable policy efforts to improve working conditions in this sector. Our analysis shows that these improvements are not only reflected in legal changes but also in voluntary agreements, which require an active role of different stakeholders. How did these policy changes come about despite the unfavourable starting conditions? We reveal that the role of trade unions indeed mattered for improving the precarious working conditions in the sector. By comparing the strategies of the trade unions in both countries, we investigate how and why trade unions get involved and advance policy change in a sector that at first sight seems to play a minor role for them.

A number of empirical studies in comparative political economy have explored the development of working conditions in the meat-processing industry (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016; Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017; Wagner Reference Wagner2015; Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016; Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016; Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff Reference Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff2017; Wright Reference Wright2011). The present study not only relies on these insights but also goes beyond it in a number of aspects: first, while most research has focused on the developments that have resulted in the exploitative working conditions of (migrant) workers in the meat-processing industry, we adopt a different perspective, focusing on recent improvements and policy changes. Second, our study stands out by virtue of its comparative approach, identifying similar trends, though achieved by different means in two countries. The dynamics that have contributed to the policy changes in this specific industry may also be enlightening for the study of labour market sectors with similar characteristics and challenges, for example, in the cleaning sector or in other low-skilled service sectors.

The study unfolds as follows: it starts by introducing the theoretical reflections on trade unions that guide the empirical analysis, before giving an overview of the peculiarities of the meat-processing industry in the United Kingdom and Germany, as well as the most recent policy changes in both countries. The following section describes the methodical approach of the study. The article then ties in with the empirical analysis, presenting and comparing the developments in both countries. The final section concludes with empirical and theoretical implications of the findings and potential foci of future research.

The ambivalent relationship between trade unions and migrants and precarious labour

Research on comparative social policy increasingly focuses on trade unions’ reactions towards migration for different parts of the welfare state (e.g. Krings Reference Krings2009; Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016; Trampusch Reference Trampusch2019). Theoretically, the role of trade unions in improving working conditions in the meat-processing industry is highly contested. The literature has described trade unions’ positions towards both precarious workers and migrant workers as ambivalent (for precarious workers, see Benassi and Dorigatti Reference Benassi and Dorigatti2015; Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015; for migrant workers, see Afonso and Devitt Reference Afonso and Devitt2016; Fitzgerald and Hardy Reference Fitzgerald and Hardy2010). While most rationales for this judgement overlap, some apply only for the group of migrants. Some studies report xenophobic attitudes of trade unions, especially in historical perspective. Moreover, it can be argued that recruiting and mobilising migrant workers are particularly resource intensive for trade unions, e.g. due to language barriers (Fitzgerald and Hardy Reference Fitzgerald and Hardy2010).

Decades before the relationship between migration and the welfare state became a key issue of the welfare state literature, Goldthorpe (Reference Goldthorpe and Goldthorpe1984) argued that trade unions can choose between two strategies with regard to migrant workers if they want to remain powerful: they can either decide to fight for migrant workers’ rights by holding up their particular “class orientation” (Goldthorpe Reference Goldthorpe and Goldthorpe1984, 339) in which no worker should be left behind or they can decide to focus exclusively on the interests of their “core” (i.e. nonmigrant) constituencies. The more recent dualisation literature assumes that trade unions rather pursue the latter strategy: although trade unions are equipped with power resources, they do not use them for improving working conditions for workers who do not constitute their core workforce (Palier and Thelen Reference Palier and Thelen2010). This has also been argued with regard to the meat-processing industry (Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016). A second strand of literature has rejected these assumptions as being too simplistic and has argued that trade unions do in fact have good reasons to engage in promoting precarious, and more specifically migrant workers’ rights (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015). Much of the critique stems from the assumption that differences between precarious migrant workers (=outsiders) and standard nonmigrant workers (=insiders) and their interests are rather artificial, not that different or at least interlinked. Fighting for precarious migrant workers’ interests can also be a perfectly reasonable strategy in order to recruit new members in a context of declining union membership. Finally, and going beyond rather rationalist explanations, fighting for all workers, and maybe even particularly the weak ones, can form a core identity of trade unions in terms of their “class orientation” (Goldthorpe Reference Goldthorpe and Goldthorpe1984). In fact, a growing literature has shown that trade unions’ strategies increasingly focus on strengthening precarious workers’ rights and migrant workers’ rights in particular. The union revitalisation literature is crucial here, which has shown that, against all odds, unions are in fact (still) successful in articulating and pursuing their interests, in large parts because they do not exclusively focus on their original core clientele, but also on precarious workers (Frege and Kelly Reference Frege and Kerry2004; see also Gumbrell-McGormick and Hyman Reference Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2013). At the same time, the literature stresses that the strategies that trade unions adopt with regard to precarious workers are also different from established approaches. Boonstra et al. (Reference Boonstra, Keune and Verhulp2011) identify five strategies that unions can adopt in order to improve the working conditions of precarious workers: first, through collective agreements; second, by taking cases to court; third, by influencing policymaking, e.g. through social dialogue; fourth, through mobilisation and organisation of precarious workers and fifth, through media campaigns which are primarily directed at the public (see also Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015).

Importantly, and this goes again back to Goldthorpe’s arguments, while most literature has treated the relationship between trade unions and precarious migrant workers as a theoretical question, it is more fruitful to treat it as an empirical question: also Benassi and Dorigatti (Reference Benassi and Dorigatti2015) have convincingly argued that trade unions’ exclusive and/or inclusive approaches should not be considered as alternative approaches because their strategies continuously evolve – and change – over time (see also Grødem and Hippe Reference Grødem and Hippe2018). Classifying a trade unions’ approach as either “positive” or “negative” towards precarious migrant workers might therefore be a highly simplified answer.

Methods and material

In order to understand policy changes in an extreme case and the role and the strategies of trade unions therein, we compare the developments in the meat-processing industry in the UK and in Germany. These cases have been selected according to the concordance method (Mill Reference Mill1843). Although the UK and Germany differ substantially in their political economy model, institutional setting and types of welfare state (e.g. Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001), labour policies in the meat-processing industry have developed similarly in recent years. In both countries, the sector has been extremely liberalised. Often unregulated labour conditions and low wages have contributed to the competitive advantage of the sector, usually in combination with low animal welfare standards (British Meat Processors Association 2017; Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017; Spiller and Schulze Reference Spiller and Schulze2008; Vogeler Reference Vogeler2019a). Surprisingly, policy changes that aim at the improvement of the situation of workers can be observed at similar points in time in the two countries. This raises the question of how these changes came along in a sector with an extremely high share of migrant as well as posted and agency workers. Our analysis focuses on the role and the strategies of trade unions and explores how these differed between the two countries. By means of a comparative analysis, we first work out similarities in policymaking for the case of labour standards in the meat-processing industry. Then, we investigate similarities and differences with regard to the role of the trade unions in this specific sector. Our analysis covers the time period from 2004 until 2017, as the Eastern enlargement of the EU in 2004 (and the corresponding free movement of workers) has significantly altered the composition of workers in the meat-processing industry in both countries (Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017; Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016).

Our analysis relies on several sources: first, we conducted an encompassing literature review for both countries. Second, we gathered written statements and publications from trade unions in both countries with the aim to understand their positions, their policy preferences and their activities. Third, we conducted a systematic media analysis in order to see how the precarious working conditions in the meat-processing industry, and especially the role of the trade unions in this process, have been addressed by the media. Media attention may bring issues on the agenda of political actors and of interest groups, such as unions (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Kepplinger Reference Kepplinger2007). Likewise, political actors and in our particular case unions may attempt to use the media to communicate their policy preferences or raise public attention.

With regard to the trade union sources, we proceeded as follows: for the German case, using the key words function, we searched the websites from the relevant trade union NGG for “fleisch” (=meat), which produced a wide range of potentially relevant publications. We conducted the same approach for the UK by focusing on material from the Trade Unions Congress (TUC), an umbrella association of British trade unions, searching the TUC’s website for “meat”. We focused on the umbrella association instead of the relevant single union Unite because a search on Unite’s website for “meat” online provided very limited results. After a detailed reading of the search results, we selected those that provided information on the trade unions’ role in addressing the working conditions, both by raising awareness for the topic and undertaking concrete actions. We included 14 sources from TUC and 22 sources from NGG. We then conducted a qualitative content analysis of all sources that explicitly dealt with the meat-processing industry. An overview of the analysed articles and statements is summarised in the supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2).

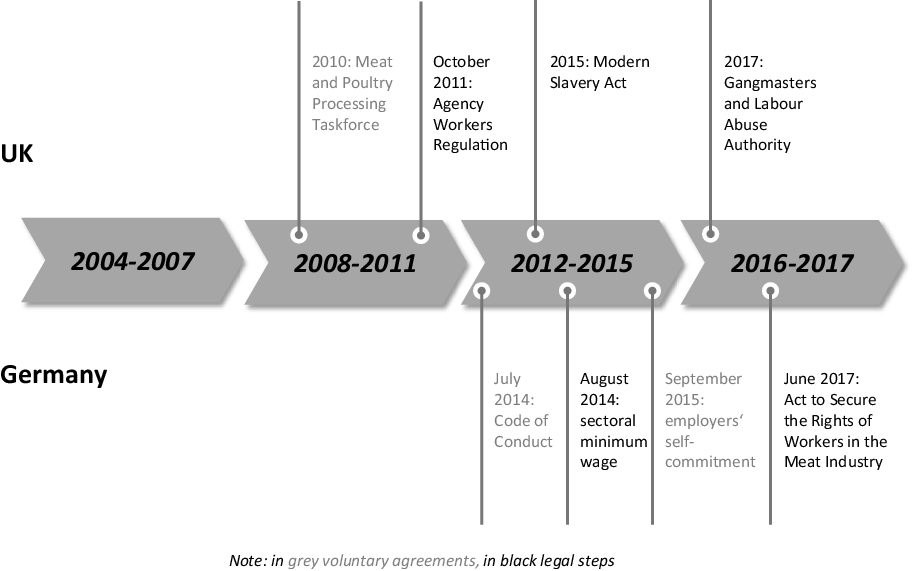

In addition, we analysed media coverage with the aim of gaining additional information on the challenges in the industry, the policy changes and the role of the trade unions therein. Our analysis comprises the years 2004 until 2017, beginning before the policy changes presented in Figure 1 were passed. For the selection of newspapers, we applied the criteria of nationwide coverage and wide circulation. To gain an overview on whether the issue was a subject of media coverage, and to consider the heterogeneity of the media landscape, we selected several newspapers for each country. The chosen newspapers include The Guardian, the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph for the UK and Die Zeit, Die Welt and Süddeutsche Zeitung for Germany. To extract the relevant articles, we adopted a step-wise approach, using the online database Nexis, which allows articles to be filtered by country, time frame, topic and newspaper through the use of keywords and operators. Table S3 in the supplementary material gives an overview. First, for the British case, we searched articles using the combination “meat” AND “working condition”, “meat” AND “labour condition”, “slaughter” AND “working condition”, “slaughter” AND “labour condition”, “abattoir” AND “working condition”, “abattoir” AND “labour condition”. For the German newspapers, we searched for “fleisch” AND “arbeitsbedingungen”, as well as “schlacht” AND “arbeitsbedingungen”. This resulted in 221 articles: 119 for the UK and 102 Germany. After excluding articles in a step-wise approach (see Table S3), only 24 articles turned out to be relevant for our case: 12 for the UK and 12 for Germany. This very small number of newspaper articles came as a surprise because in the current literature on labour standards in the meat-processing industry, at least for Germany, the argument prevails that media coverage and public opinion were decisive in triggering the policy changes (Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016; Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016). For the remaining 24 articles, we conducted a qualitative analysis, focusing especially on the main content and the relevant actors that were mentioned. An overview of the analysed articles is summarised in Table S4 in the supplementary material.

Figure 1 Policy changes for workers in the meat-processing industries in the UK and Germany.

Case study – the meat-processing industries in Germany and the UK

An overview of the meat-processing industries in Germany and the UK

Intensive animal farming is an important pillar of agricultural production in both countries. In the UK, animal production accounts for 60%, in Germany for 49% of agricultural output (European Commission 2017a, 2017b). Both livestock sectors have a strong export orientation. The German livestock industry in particular focuses primarily on cost leadership which is reached by high levels of intensification. This often goes along with poor animal welfare and the exploitation and pollution of natural resources (BMEL 2015; Grethe Reference Grethe2017; Möck et al. Reference Möck, Vogeler, Bandelow and Schröder2019). Similarities also exist between the structure of the industries, with an increasing concentration of market players. In Germany, 60% of pig processing is carried out by the largest four players in the market (Tönnies, Vion, Westfleisch and Danish Crown), and one-third of all slaughtered pigs is slaughtered by one player, namely the Tönnies Group (agrarheute 2017). Contrary to other industrial branches, the meat industry has not attained major product differentiation; cost advantages are achieved either by economies of scale or at the expense of animal welfare and/or the employees (Spiller and Schulze Reference Spiller and Schulze2008). Currently, policymakers and actors along the production chain are making increasing efforts to improve animal welfare in livestock farming (Vogeler Reference Vogeler2017, Reference Vogeler2019b). Retailers especially foster a differentiation of animal products by labelling their products according to animal welfare criteria, thereby setting new standards in the sector (Lundmark et al. Reference Lundmark, Berg and Röcklinsberg2018). However, product differentiation is limited to animal welfare and does not (yet) cover the field of working conditions in the processing chain. This is remarkable, considering the critical interaction between animal handlers and animal welfare. In particular at abattoirs, the rising demand for faster production often leads to rough handling of the animals and serious animal welfare infringements (Velarde and Dalmau Reference Velarde and Dalmau2012). These problems are exacerbated by the use of untrained and low-paid workers and by language barriers with migrant workers (BMEL 2015). Working conditions in the meat-processing industry include high cycle rates, heat, noise and shift work (Hans-Böckler-Stiftung 2017). Wages are often below the minimum wage and the share of permanent staff is low (Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017). The high proportion of agency, posted and subcontracted workers makes it difficult to give precise statements on the composition of workers (Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016). The British meat-processing industry relies to a large extent on agency workers. It is estimated that in the UK’s red and white meat-processing industry over 60% of the workforce are migrants (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs et al. 2017). For Germany, the trade union NGG (Gewerkschaft Nahrung-Genuss-Gaststätten; Food and Restaurant Workers’ Union) estimates that two-third of employees are subcontracted workers, most of whom are migrants (DGB 2017b). Wagner and Hassel (Reference Wagner and Hassel2016) estimate that posted workers account for 38% of the workforce in the German meat-processing industry.

Tying in with this brief overview of the structure of the meat-processing sector in both countries and the challenges for workers, the subsequent sections focus on the policies that address workers in this specific sector in both countries.

Policy changes in the meat-processing industry in the UK

Immediately following EU enlargement in 2004, the UK opened its labour market for workers from the new EU accession countries. As a consequence, many workers from Central and Eastern European countries came to work in the British meat-processing industry. The high influx of migrant workers benefited the industry as it had been struggling to fill the jobs with UK workers due to the unfavourable working conditions (British Meat Processors Association 2017; Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017). After EU enlargement, so-called A8 nationals (migrants from the new EU accession countries) only had to register with the Worker Registration Scheme, which operated from 2004 to 2011 and aimed to keep track of how the UK labour market was affected by these workers (see also Andersen Reference Andersen2010). Employment agencies play a crucial role in recruiting especially migrant workers for the meat-processing industry (Lever and Milbourne Reference Lever and Milbourne2017, 307). A report by the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in March 2010 uncovered severe problems in working conditions in the sector, with migrant workers being treated particularly badly. The EHRC report found that violations of legal requirements, ethical trading standards and human rights were widespread, highlighting among others a worse treatment of agency workers compared to standard workers, physical and verbal abuse, as well as concerns related to health and safety issues (EHRC 2010, 10–13). The EHRC director stated that he would consider regulative policies if the situation did not change within the next year (TUC 2010). A direct consequence was the formulation of the Agency Workers Regulation in October 2011, which improved the position of agency workers by granting them the same working conditions as regular workers after they had completed a qualifying period of 12 weeks (James Reference James2011). Other significant legal changes were the Modern Slavery Act (2015) and the transition of the Gangmasters Licensing Authority (GLA) into the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority (GLAA) in 2017 (Heasman and Morley Reference Heasman and Morley2017, 26–27). The former introduced new reporting obligations for businesses on the prevention of exploitative working conditions which can be classified as modern slavery (Heasman and Morley Reference Heasman and Morley2017, 27). The GLAA ensures that businesses comply with legal employment standards (Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority 2017). Another consequence of the inquiry was the EHRC’s strategy of encouraging the meat-processing industry to actively promote change (EHRC 2012, 3). Instead of regulation, changes within the sector should be achieved through voluntary agreements which have proven successful in other sectors (Töller Reference Töller2017). Most importantly, the Meat and Poultry Processing Taskforce was initiated in order to improve working conditions within the industry, with the participation of a large share of relevant stakeholders. Furthermore, supermarkets were identified as playing the key role for bringing about improvements as 80% of the industry’s products are produced for supermarkets. While most supermarkets do conduct independent audits on a regular basis, these are often focused on other issues than working conditions (such as e.g. health, safety, hygiene). Moreover, they are often announced in advance and do not allow workers to talk to inspectors privately, which hampers the effectiveness of the audits. Apart from audits, supermarkets have also established supplier standards in line with the Ethical Trading Initiative base code (ETI 2014) and try to improve awareness of the topic, e.g. through workshops and training schemes (EHRC 2012).

Policy changes in the meat-processing industry in Germany

Following EU enlargement in 2004, Germany restricted labour market access for citizens from new EU accession countries until 2011. Nonetheless, the German meat-processing industry has increasingly relied on posted workers since 2004. The legal basis is the German Posted Workers Act (1996), which implements the EU Posting of Workers Directive. The German Posted Workers Act established different standards for different sectors: for the construction sector, for example, it was agreed that the working conditions of the host country should apply for posted workers, while for the meat-processing sector, the working conditions of the sending country applied (Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016, 168). Consequently, firms in the meat-processing industry relied heavily on posted workers, meaning they could pay low wages and grant low labour standards. Both factors gave the German meat-processing industry a competitive advantage (Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016, 164). In fact, many European meat-processing businesses even moved parts of their production to Germany in order to benefit from cheap labour (Hans-Böckler-Stiftung 2017, 16). Attempts to introduce a sectoral minimum wage in the sector and to declare it generally binding via the German Posted Workers Act, which was pushed by the Social Democrats and the then social democratic Minister of Labour and Social Affairs, failed in 2007 (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016), but renewed attempts succeeded in 2014. Employers and employees agreed on a sectoral minimum wage of 7.75€ per hour, which would be gradually raised in four steps, and come into effect from July 2014 (NGG 2014). Due to procedural delays, the sectoral minimum wage was eventually only in place from August 2014 (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016, 81). One important reason for the agreement in the sector was the upcoming introduction of a nationwide statutory minimum wage. Against this background, some low-wage sectors could set minimum wages below the level of the statutory minimum wage for a transitional period (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016). Besides the introduction of a sectoral minimum wage, another important legal step was the Act to Secure the Rights of Workers in the Meat Industry, which was adopted in June 2017. The act holds businesses responsible for their subcontractors, and meat companies that engage subcontractors are liable for their social insurance contributions. Other elements of the law oblige employers to provide work material for free, to pay wages instead of granting other benefits such as accommodation or transportation and to increase documentation duties (DGB 2017a). It is remarkable this law was enacted at all, since it passed through parliament without receiving much public attention. This secretiveness was a measure to prevent businesses from exerting influence as well as to protect those involved in the legislative procedure (DGB 2017a; Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017).

As in the British case, voluntary agreements play an important role. Already in July 2014, the four biggest German slaughterhouses adopted a Code of Conduct in order to improve working conditions, for example, by granting workers appropriate accommodation. Moreover, in September 2015, an “employers’ self-commitment for more attractive working conditions” was adopted; six meat-processing businesses, Sigmar Gabriel (then minister of economy) and the NGG were involved in bringing this about (Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff Reference Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff2017, 536). One rationale of the employers to put forward this voluntary agreement was to prevent direct state intervention (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016, 84). The agreement’s main aims were to ensure that subcontracted workers were employed according to German labour and social standards, to increase the permanent workforce, to provide vocational training and qualification and to introduce measures facilitating the integration of migrant workers (SPA 2015, 13).

Figure 1 gives an overview of the depicted developments in the British and German meat-processing industries following EU enlargement in 2004. Both countries have undertaken legal actions directed at improving working conditions in the sector, though voluntary agreements also play a role. Interestingly, British regulation even slightly preceded German regulation.

The role of trade unions in the British and German meat-processing industries

Following the overview of the policy changes in the meat-processing industries in both countries, this section will investigate the role of trade unions in shaping these developments.

Trade unions in the British meat-processing industry

British trade unions started to address migrants’ interests since the 1970s (Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Turner2013). In the General Council Statement on European Migration from September 2006, i.e. against the background of EU enlargement in 2004, TUC stressed that they clearly opposed the exploitation of migrant workers (TUC 2006). Notably, TUC argued that this was also in the trade unions’ very own interest because equal rights for migrant and nonmigrant workers could prevent that migrant workers are considered as cheap labour and therefore as a threat to nonmigrant workers. In 2007, TUC set up the TUC Commission on Vulnerable Employment in order to move the topic of exploitative working conditions on the political agenda (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015). This can be considered an important step in trade unions’ efforts to fight for precarious workers’ rights. Importantly, the Commission also acknowledged that workers in the meat-processing industry were a particularly vulnerable group. Vulnerable work was defined as “precarious work that places people at risk of continuing poverty and injustice resulting from an imbalance of power in the employer-worker relationship” (TUC 2007, 3). With the aim of initiating a new dialogue between experts and stakeholders, the Commission involved actors from both business and trade unions, as well as experts. Since then, there have been several successes for British trade unions in improving precarious working conditions through collective agreements, as well as through the organisation of new workers (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015, 395) in many areas of precarious work, and also with regard to migrant workers (Mustchin Reference Mustchin2012).

The efforts of the Transport and General Workers’ Union (T&G) (which in 2007 became Unite the Union after having merged with the union Amicus) in the meat-processing industry are widely considered as a successful example of new and relatively successful union mobilisation strategies (Wright and Brown Reference Wright and Brown2013; Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman Reference Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2013). In fact, T&G (and later Unite) was a key actor in placing the issue of exploitative working conditions on the political agenda in the first place and on initiating major improvements for workers. T&G’s engagement with the issue began in the mid-2000s. Their efforts were part of a broader strategy of strengthening the role of trade unions in fighting various forms of precarious work. This strategy consisted of several components: organising workers in the whole sector, blaming supermarkets as the most powerful actors in the supply chain, and collecting evidence on the exploitative working conditions in the meat-processing industry (Wright Reference Wright2011; Wright and Brown Reference Wright and Brown2013; The Guardian 2010). T&G’s organising strategy consisted of forming a special group which was composed of both activists and stewards from the entire industry and supported by the union. The aim was to coordinate the whole campaign and to provide actors with strategies and information. Mobilisation on concrete and presumably easy-to-achieve issues – such as clean boots – was then promoted in individual workplaces in order to strengthen workers’ awareness for trade union activities as well as their likely successes (Wright Reference Wright2011). As a second step, the union decided to focus on one single issue, namely the “corrosive impact of agency workers on labour standards” (Wright Reference Wright2011, 40). After trying to reach improvements on the employers’ level turned out to have only limited success, supermarkets became the focus of attention, as their demands for cost pressure were considered to be one of the key problems. Unite worked with the Ethical Trading Initiative – of which many supermarkets are members – in order to sensitise supermarket representatives to the challenges in the industry. Apart from that, Unite also scandalised meat-processing practices at factories producing for the retailer Marks and Spencer (M&S), which resulted in the creation of two “ethical model factories” (Wright Reference Wright2011, 41). Unite also initiated public protests at the supermarket chain Tesco (see also The Guardian 2009). Most notably, Unite bought Tesco shares in order to be able to participate in the Tesco shareholder meeting and to push forward a resolution aimed at ending agency worker discrimination in the meat-processing industry (TUC 2009). Although in the end, the resolution was not successful, many powerful Tesco investors supported it, which was considered another remarkable success (Wright Reference Wright2011; The Guardian 2010). Finally, it was Unite who initiated the EHRC inquiry and thus the report on the exploitative working conditions in the sector (Wright Reference Wright2011; The Guardian 2010; TUC 2011a), which received not only a lot of public attention but also led to a number of policy changes (as described in the previous section). Unite particularly accused the supermarkets’ cost pressure as being responsible for the disastrous working conditions: “Britain’s supermarkets should hang their heads in shame” (TUC 2010). Already before the EHRC report was published, the British supermarket chain ASDA proactively approached Unite and promised to adjust the working conditions of agency and permanent workers, as well as enabling agency workers to become permanent workers within 12 weeks (Wright Reference Wright2011, 43; TUC 2011b). Apart from putting the issue on the political agenda and contributing to the improvement of working conditions, also by moving a substantial number of workers from temporary to permanent employment and changing the practices of agencies, a measurable outcome of Unite’s success is the considerable increase in union membership and the number of workers covered by collective bargaining (Wright Reference Wright2011, 43).

Trade unions in the German meat-processing industry

Since the encompassing labour market reforms in Germany around the turn of the century (Blum and Kuhlmann Reference Blum, Kuhlmann, Schubert, de Villota and Kuhlmann2016), at least some trade unions have increasingly focused on precarious workers (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015). The reasons for that are not only normative considerations of social justice, rather it is increasingly acknowledged that precarious employment potentially undermines standard employment and consequently also the trade unions’ bargaining power. Moreover, precarious workers are considered as a “potential recruitment pool” (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015, 389). Besides collective bargaining, German unions have also campaigned with the aim to organise precarious workers. In addition, they have tried to promote better working conditions through the initiative Gute Arbeit (Good Work) (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015). In this regard, German trade unions generally acknowledge the need of representing migrant workers’ interests (Tapia and Turner Reference Tapia and Turner2013), although it also needs to be kept in mind that, following EU enlargement in 2004, they strongly pushed for transitional periods before the full free movement of labour should be enacted (Krings Reference Krings2009).

In Germany, workers who are employed in the meat-processing industry are generally represented by the NGG, which is the oldest trade union in Germany and part of the umbrella organisation DGB (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund; Federation of German Trade Unions). The NGG had also been the first union within the DGB that, already in 1999, favoured the introduction of a statutory minimum wage (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016). When attempts to introduce a sectoral minimum wage in 2007 failed, a key problem was that the four big meat-processing businesses were not organised in an employers’ association; so, the NGG lacked a reference association to negotiate with. The businesses’ negative stance towards an agreement with the trade unions changed in subsequent years, notably after Belgium officially filed a complaint against the undermining of wages in the German meat-processing industry to the European Commission. Simultaneously, workers in France protested against Germany’s cheap labour strategy. In addition to these international pressures, national negative media coverage increased (Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016; Wagner and Hassel Reference Wagner and Hassel2016). The newspaper Die Zeit especially presented the working conditions in the meat-processing industry as scandalous on multiple occasions (see also supplementary material, Table S4). Also, governmental actors, most notably the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, put the industry under considerable pressure. In 2013, the NGG addressed the companies in the meat-processing industry in order to introduce a sectoral minimum wage. Given the rising external pressure, the four big slaughterhouses as well as the Employers’ Association for the sector (ANG) supported this position. Due to the absence of a negotiation partner on the employer side, a regional association, namely the VdEW (Verband der Ernährungswirtschaft; Food Industry Association), was selected to negotiate on behalf of the employers. However, the VdEW stopped the negotiations because they opposed the trade unions’ demands regarding equal wages in Eastern and Western Germany, as well as the suggested level of the minimum wage. After an intervention by the president of the Confederation of German Employers’ Association, Ingo Kramer, the ANG became the new negotiation partner and eventually agreed with the NGG on a sectoral minimum wage (Jaehrling et al. Reference Jaehrling, Wagner and Weinkopf2016, 79–81).

Against this background, one could conclude that the introduction of the sectoral minimum wage did not result from union strength but rather from the desire of the meat-processing industry to address the problem of pressure exerted by both the public and some policy actors that was threatening their image (Wagner and Refslund Reference Wagner and Refslund2016; Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff Reference Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff2017). While this ascribes a less proactive position to the trade unions, it is only half of the story: first, the NGG had advocated for introducing a minimum wage for years. Second, trade unions did in fact also apply innovative strategies in order to improve working conditions in the sector: as Wagner’s (Reference Wagner2015) case study on a German meat-processing firm with a Polish subcontractor shows, coalitions between local civil society organisations and trade unions were able to achieve major improvements for workers in the meat-processing industry, at least in some factories. After a local community initiative became aware of the precarious working situation of posted workers in one factory, they built a coalition with the NGG and decided to raise public awareness for the topic through media reporting, thereby targeting not only the firm who had hired the subcontracting firm but also municipalities who provided housing for the posted workers. As a consequence, the firm terminated the cooperation with the subcontractor. Moreover, the NGG achieved that all employees of the subcontractor were taken over by a German agency. Besides pushing for the sectoral minimum wage, the NGG was also involved in the initiative “employers’ self-commitment for more attractive working conditions”, yet it remained critical of the self-commitment’s actual impact (Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff Reference Weinkopf and Hüttenhoff2017, 537).

The role of trade unions in the British and German meat-processing industries compared

The previous sections have revealed that in both countries, trade unions mattered for bringing the exploitative working conditions in the meat-processing industry on the political agenda, partly together with other actors. As for the UK, the crucial role of trade unions in improving working conditions in the meat-processing industry by relying on innovative mobilisation strategies has already been highlighted by several authors (Wright Reference Wright2011; Wright and Brown Reference Wright and Brown2013; Gumbrell-McGormick and Hyman Reference Gumbrell-McCormick and Hyman2013). Keeping in mind the different strategies for addressing precarious work as suggested by Boonstra et al. (Reference Boonstra, Keune and Verhulp2011), the British trade unions’ considerable efforts of organising and mobilising workers stand out, which were accompanied by innovative strategies to attract public attention, e.g. by publicly blaming supermarkets, which was taken up by the media. What is more, cooperation with other actors – notable the Ethical Trade Initiative – proved successful, as well as innovative strategic actions such as buying Tesco shares in order to be able to participate in and influence the shareholder meeting. Most importantly, however, were the trade unions’ efforts to collect evidence on exploitative working conditions in the meat-processing industry and initiate the inquiry which led to the EHRC report. Its publication can clearly be seen as a focusing event that promoted policy change (Birkland Reference Birkland1998).

In contrast, although trade unions were involved in recent improvements in the meat-processing industry, the role of the trade unions in Germany cannot so clearly be characterised as a ‘success story’. Our evidence suggests that the NGG focused on the introduction of a sectoral minimum wage, indicating that they tried to improve working conditions in the sector by rather traditional means of collective agreements. While the NGG had in fact pushed for a minimum wage for several years, the NGG’s attempt was only successful after the employers had agreed on negotiations with the trade unions (following both public and political pressure). Still, it can be argued that also German trade unions adopted additional strategies to push for better working conditions, e.g. through alliances with civil society organisations at the local level and the accompanying media coverage, which can at least on the domestic level be considered a key factor for employers to agree on negotiations (Wagner Reference Wagner2015).

Taken together, the findings reveal that although trade unions did matter for improving working conditions in both countries, their channels of influence as well as the strategies through which trade unions contributed to this differed remarkably, highlighting different causal pathways in both processes. The British case can clearly be seen as an example of successful union revitalisation by relying on innovative strategies. In contrast, the German story exhibits a strong reliance on improving wages through the introduction of a sectoral minimum wage, indicating a more traditional approach to improving workers’ rights. Wagner (Reference Wagner2015) suggests that strategies such as cooperation with other actors and scandalisation of working conditions through the media also played a role. Yet, our evidence does not hint to an orchestrated trade union campaign as compared to the British one, especially when it comes to the organisation and mobilisation of workers.

Conclusion

Our analysis has traced the development of working conditions in the meat-processing industry in the UK and Germany since 2004. Prior to the reforms analysed in this article, the similar structures of the sectors in both countries suggest that the meat-processing industry in both countries had converged into a single liberal model, in which low institutionalised coordination between actors (which came at the expense of employees) served key roles in giving each country a competitive advantage. Against this background, it is surprising that an improvement of working conditions was made on the policy level at all. Our analysis focused on the role of trade unions within these processes. It revealed how policy change can happen despite unfavourable conditions and weak actors, providing these actors act jointly and make strategic use of situational conditions (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984; Bandelow et al. Reference Bandelow, Vogeler, Hornung, Kuhlmann and Heidrich2019) rather than of institutionalised channels of influence. In contrast to what the literature on dualisation suggests, trade unions do take care of the interests of precarious workers and are increasingly pursuing new ways of exerting influence, especially when it comes to migrant workers. The present analysis traced and compared the different strategies of trade unions in the two countries. The future role of trade unions in further improving working conditions in the meat-processing industry clearly does not only depend on their institutional embeddedness as well as their innovative power but also their personal and financial resources. What is more, while the British example indicates trade union success, it is questionable if such efforts can be maintained over a longer period of time (Keune Reference Keune, Eichhorst and Marx2015).

What was the actual impact of the policy changes on working conditions in the meat-processing industry? The legislative changes and voluntary agreements reveal that improvements – albeit incremental – have taken place. At first glance, this seems to support the argument that an improvement in working conditions is possible even in a least-likely case. At second glance, however, this finding needs to be treated with care: the analysis has shown that improvements were meant to be achieved through a policy mix of legislative changes and voluntary agreements. On the one hand, the effectiveness of the legislative changes should be questioned as the meat-processing industry’s compliance with the law is not properly controlled, meaning the enforcement of its labour standards is still not guaranteed. In fact, media reports in both countries continue to expose poor working conditions (The Guardian 2015) as well as failures to implement existing measures (Süddeutsche Zeitung 2017), and trade unions continue to criticise these problems (NGG 2016). On the other hand, the strong reliance on voluntary agreements means that stakeholders along the production chain are required to agree on improved working conditions for their employees. Even though working conditions are not yet a major issue of product differentiation, we expect that retailers in particular might exert their market power in order to foster improvements in this field as they increasingly do in other areas of food production. The critical role of the retail sector in advancing structural changes is currently apparent in the field of farm animal welfare (Vogeler Reference Vogeler2019b). Similar developments may occur if public attention is drawn to the existing challenges facing workers and if the awareness of the close interaction between animal welfare and workers’ welfare increases. The fact that employer associations are collaborating with trade unions in order to improve working conditions in the sector shows that improvements are also supported by employers wishing to avoid a loss of reputation. In particular, the role of the media suggests that future changes to improve the situation of workers are more likely to be introduced by employers as a consequence of public pressure.

Going beyond the relevance of the results of this study for the specific sector of the meat-processing industry, our findings regarding the different strategies of trade unions in advancing policy change are insightful for other sectors. This is especially true for sectors that share similar characteristics in terms of the socioeconomic composition of the labour force, for example in the cleaning sector or in other low-skilled service sectors. The current challenges of skill shortage and demographic developments will on the one hand contribute to the rise of the share of migrants in such sectors, which may give trade unions even higher incentives to get involved with this group of workers. Likewise, skill shortage might ease the precarious situation of workers in such sectors in terms of better payment due to shortages in labour supply. The latter can currently be observed in the agricultural sector in both the UK and Germany.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000112

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.