[Content advisory: This article discusses harassment and discrimination in archaeology, including accounts of sexual assault.]

This article is the second in a two-part series that reviews and analyzes research on harassment in archaeology and related fields. Whereas the first article (Voss Reference Voss2021) documented the extent of the problem, this one outlines evidence-based solutions that can disrupt cultures of harassment in archaeology. The approaches outlined here build on two public health paradigms: the social-environmental model and trauma-informed care. Throughout, I draw on 35 years of experience in archaeology, including student and professional roles in cultural resource management (CRM), museums, and academia.

Although harassment occurs in archaeology at epidemic rates, there are key actions that can both stop harassment before it starts and reduce the impact of harassment on survivors. In general, interventions are most likely to succeed when they are developed in collaboration with survivors and other vulnerable archaeologists, when they leverage organizational capabilities, and when they build on already shared core values of collaboration and collegiality in archaeology.

What We Now Know about Harassment in Archaeology

The term “harassment” refers to a wide range of discriminatory and illegal practices that occur in educational and workplace environments. Harassment includes physical and nonphysical behaviors that convey hostility, objectification, exclusion, or second-class status based on the perceived gender or sexual orientation of the person being targeted. Nonphysical harassment “can result in the same level of negative professional and psychological outcomes as . . . instances of sexual coercion” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). A target's gender identity, sexual orientation, age, race, ethnicity, national origin, class background, queerness, or disability may compound the individual's vulnerability to harassment (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991). Increasingly, the term “identity-based harassment” is used to encompass a wide range of discriminatory and predatory behaviors.

The fight against harassment in archaeology stretches back to the late nineteenth century. Since the 1970s, gender equity research has clearly identified harassment as a major factor adversely affecting women archaeologists, LGBTQIA+Footnote 1 archaeologists, and archaeologists of color (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994). During the 2000s and 2010s, many archaeological professional societies adopted strongly worded statements against harassment. Unfortunately, these policies alone have not been effective in preventing further harassment. Recent research indicates that 15%–46% of men archaeologists and 34%–75% of women archaeologists have experienced one or more harassment events during their careers. A staggering 5%–8% of men archaeologists and 15%–26% of women archaeologists report unwanted sexual contact, including sexual assault (Voss Reference Voss2021:Table 1).

Researchers have identified the following eight distinctive patterns to harassment within archaeological workplaces and learning environments (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2020; Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Coto Sarmiento et al. Reference Coto Sarmiento, Anés, Martinez, Alonso, Pérez, Martínez and Gómez2018; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Jalbert Reference Jalbert2019; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017; Radde Reference Radde2018; Rocks-Macqueen Reference Rocks-Macqueen2018; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018):

(1) Harassment occurs in all archaeological sectors (CRM, government agencies, museums, heritage, and academia) and all settings (field sites, laboratories, classrooms, offices, museums, conferences).

(2) Archaeologists are most frequently harassed by other archaeologists, often by members of their own research team.

(3) Harassment is most commonly directed at archaeologists in entry-level positions.

(4) Women archaeologists are most commonly harassed by men and by supervisors.

(5) Men archaeologists are harassed by both men and women in roughly equal frequencies, and they are harassed by peers more commonly than by supervisors.

(6) Women archaeologists are more likely than men archaeologists to be harassed because of their family status.

(7) Archaeologists of color, ethnic minority archaeologists, nonbinary archaeologists, LGBTQIA+ archaeologists, and archaeologists with disabilities report harassment at higher-than-average rates.

(8) Harassment in archaeology is learned intergenerationally, through early career experiences and through senior archaeologists encouraging or pressuring junior archaeologists to participate in harassing behavior.

Research and survivor testimonies have documented the negative impacts of harassment. Survivors report “feeling ‘vulnerable,’ ‘powerless,’ ‘not in control,’ ‘isolated,’ or like ‘prey’” (Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017:714). They often become insecure about their own abilities and career futures (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015:28). According to Nelson and colleagues (Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017:715), “The continual processing and decision making that goes into negotiating a hostile work environment and maintaining employment can be exhausting and lead to a reduction in mental and physical health.” This cognitive and psychological burden draws time, energy, and attention away from professional activities, compounding the initial impact of harassment, and in some cases, pushing archaeologists out of the field (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017).

Barriers to Change

Why has harassment in archaeology persisted, despite decades of activist interventions and thoughtful anti-harassment policy statements by archaeological organizations? There are five key barriers to change: normalization, exclusionary practices, fraternization, gatekeeping, and obstacles to reporting.

Normalization

In survey research on harassment, respondents “regularly identified harassment as part of the ‘culture’ of archaeology” (Radde Reference Radde2018:248–249) and found that harassment is “one of the unspoken but socially expected behaviors of archaeological workplaces” (Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody, Wright and Dekle2018:277; emphasis in original)—in sum, “que [acoso] es algo que ocurre y que es normal” (that [harassment] is something that happens and that is normal; Coto Sarmiento et al. Reference Coto Sarmiento, Anés, Martinez, Alonso, Pérez, Martínez and Gómez2018:33).

Like many archaeologists, I was socialized to accept harassment as normal, and I unconsciously reproduced some of the attitudes and behaviors I witnessed early in my career. For example, some supervisors regularly teased me, so when I became a supervisor myself, I sometimes teased my subordinates and encouraged others to join in, forgetting how uncomfortable it was to be the target of jokes. I also tolerated inappropriate behavior. On one project, for instance, a subordinate routinely used sexualized language when talking to other team members. I did not like it, and I could tell that other project members were also uncomfortable. But despite my supervisory role, at the time, I felt unable to address the subordinate's inappropriate conduct directly.

The normalization of harassment also affected my mentoring style. Until only a few years ago, when other archaeologists approached me for advice about how to handle harassment, I usually encouraged them to develop a tough skin and persevere rather than directly challenge or report the harasser. This was how I had survived throughout my career, and it echoed the advice I had received from senior mentors. Looking back, I recognize my past behaviors in what van der Vaart-Verschoof (Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2019) describes as

the hard-ass female professor. . . . These are usually women in their 50s or 60s, who came up in academia and archeology in a time when things, generally speaking, were just so much worse for women. They had to fight for everything, and—completely unfairly btw—had to prove themselves to a much higher standard than their male peers. And for some reason, I have found that many of them seem to be even harder on young women, and to hold them to a much higher standard.

It is painful for me to reflect on how I participated in reproducing the normalization of harassment in archaeology. Recent research shows that I am not alone: cultures of harassment in archaeology are learned and reproduced intergenerationally (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019:283). Understanding this process of normalization helps us realize how important it is for every archaeologist to participate in challenging harassment.

Exclusionary Practices

The discipline as a whole: white, middle class, heterosexual, First World, and able-bodied [Wylie and Nelson Reference Wylie, Nelson, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994:xi].

Archaeology expresses a gender regime that valorizes everything connected with the active (and actively) heterosexual male, or perhaps more specifically, everything connected with a certain type of masculinity [Moser Reference Moser2007:259].

Fieldwork is a low-risk environment for perpetrators . . . and a high-risk environment for marginalized individuals . . . [with] increased risk to non-male and non-heterosexual individuals [Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2020:2].

Stereotypes of risk-taking, adventurous, white, masculine archaeologists support a widely shared but often unspoken belief that pursuing archaeological research is more important than personal or community safety—in fact, that the risks incurred add value to the research itself. This attitude “includes notions about romanticized adventure, physical endurance, and hard drinking. . . . All archaeologists then must embody hegemonic masculinist performances in field settings, regardless of their biological sex, in order to be successful, ideal professionals” (Geller Reference Geller, Amoretti and Vassallo2016:160). Archaeologists who resisted or reported harassment have consequently been “ridiculed” and “stereotyped as hysterical, thin-skinned, naïve, and humourless” (Wylie Reference Wylie, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994). When risk-taking is a disciplinary norm, reporting harassment exposes the complainant to further stigma and exclusion.

Fraternization

In education and professional contexts, fraternization refers to intimate romantic and sexual relationships among colleagues. Fraternization has a long history in archaeology. Initially, marriage to a cisgender man archaeologist was one of the few career pathways available to women archaeologists. Since the 1970s, joint appointments for archaeological couples have been actively promoted as a way of improving gender equity. In private-sector CRM in the United States, government-contracting preferences for women-owned business enterprises encouraged heterosexual archaeology couples to form jointly owned companies. All of these measures reinforced the connection between intimate relationships and women's careers in archaeology.

Even among archaeologists of equal rank, fraternization can generate conflicts of interest. Actual or perceived favoritism by one archaeologist toward that person's intimate partner can result in indirect harassment toward others and produce a hostile working or learning environment. Subordinates may feel doubly reluctant to report harassment if their abuser's intimate partner has a role in the investigation, or if there is a potential for retaliation by the nonharassing partner.

The problem of fraternization is heightened when intimate relationships form between supervisors and subordinates. Survivor testimonies and bystander accounts illustrate that whatever the intentions of the senior archaeologist, junior colleagues often interpret invitations and advances within the power-laden context of their professional relationship:

I got employment running the archaeology laboratory and learning various laboratory analyses from the woman assistant laboratory director. After a year of loneliness and poverty I gave into her advances. She cooked for me, she bought me presents, she gave me a job [She 2000:170].

The professor . . . asked if I was performing oral sex on my supervisor . . . and then proceeded to hit on me. . . . As he was a professor and I [was] “only” a student, I felt like there was nothing I could do about his wildly inappropriate behavior [van der Vaart-Verschoof Reference van der Vaart-Verschoof2019].

I felt I could not say no without jeopardizing my grade or my recommendation. . . . I have suffered greatly from having participated in unwelcome sex and became severely depressed [Anonymous student, quoted in Bikales Reference Bikales2020].

We have yet to develop best practices for addressing how the prevalence of fraternization in archaeology impacts disciplinary culture. Adopting principles of full disclosure and appropriate recusal would be a good beginning toward reducing actual and perceived bias related to intimate partnerships in archaeological learning environments and workplaces. Ensuring that intimate partners are not placed in positions of supervision or evaluation over each other and—whenever possible—are assigned to different teams or departments, could mitigate the potential for bias. Given that the power imbalances and transactional potentials in senior-junior intimate relationships “make it hard to determine whether these relationships are consensual” (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019:280), clear policies against fraternization among archaeologists of different ranks are necessary to transform archaeological cultures of harassment.

Gatekeeping

Harassers are often gatekeepers who have the power to restrict a researcher's access to the community and information. In such cases, harassers are often aware of their power and authority in relation to the researcher and [their] work, and assume [their] dependency [Kloß Reference Kloß2017:405].

Archaeological research requires collaboration as well as permits, funding, laboratories, collections, and specialized equipment. As archaeologists, we depend on gatekeepers—those who can approve or deny applications, petitions, and requests—for access to the fundamental building blocks of our careers. Disciplines such as archaeology that are “hierarchical with strong dependencies on those at higher levels . . . are more likely to foster and sustain sexual harassment” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:4). Although most archaeologists exercise their gatekeeper roles with integrity, safeguards are necessary to ensure that subordinates can report gatekeepers’ misbehavior without risking their careers.

Obstacles to Reporting

Current reporting procedures often increase the vulnerability of survivors rather than protect them. The low number of reports “suggest that our disciplinary culture either does not encourage reporting, that reporting harassment is socially unsanctioned, or that fear of retaliation is a significant factor” (Radde Reference Radde2018:244). As Hodgetts and colleagues (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:37) observe,

Most of these incidents take place within small communities of people—field crews, university departments, CRM offices—that are hierarchically structured. . . . Because someone in authority often perpetrates the negative experiences, reporting could result in job loss or reduced access to professional opportunities.

Consequently, few archaeologists who have experienced harassment actually report their harassers. Survey respondents (Radde Reference Radde2018:244, 249, 250) made the following statements:

• “We are too concerned about losing our careers to make a formal report.”

• “At the time I was not in a position to challenge, and [I] feared being removed from projects.”

• “I knew that if I reported it, they would make my life miserable.”

• “Sometimes it is more trouble than it's worth and you don't want to worry about retaliation or being labeled ‘problematic.’”

Several times, I did report harassment to direct supervisors, who were mandated by law and by institutional policy to take formal action on complaints. None did. One scolded me: “If you plan to run away every time a sexist archaeologist tries to stop you from reaching your goals, you might as well quit right now.” Another supervisor warned that formal reporting would expose me to retaliation. In most cases, however, my reports were just ignored.

In the absence of effective channels for formal reporting, victims of harassment are increasingly turning to social media, anonymous testimonies, and collective action as means for “distributing the risk of complaint” (Awesome Small Working Group [ASWG] 2019:18). Digital activism and collective complaint are forcing institutional responses and generating support for individual survivors.

Public Health Approaches to Disrupting Cultures of Harassment

The pervasive patterns of harassment in archaeology and barriers to change indicate that a public health approach may be helpful. This perspective does not absolve individuals of responsibility, but it suggests that initiatives to reduce or eliminate harassment will be more effective if they address contributing factors at multiple levels. The remainder of this article adapts two evidence-based approaches—the social-environmental model and trauma-informed care—to identify interventions that can prevent harassment in archaeology, support survivors, and hold harassers accountable.

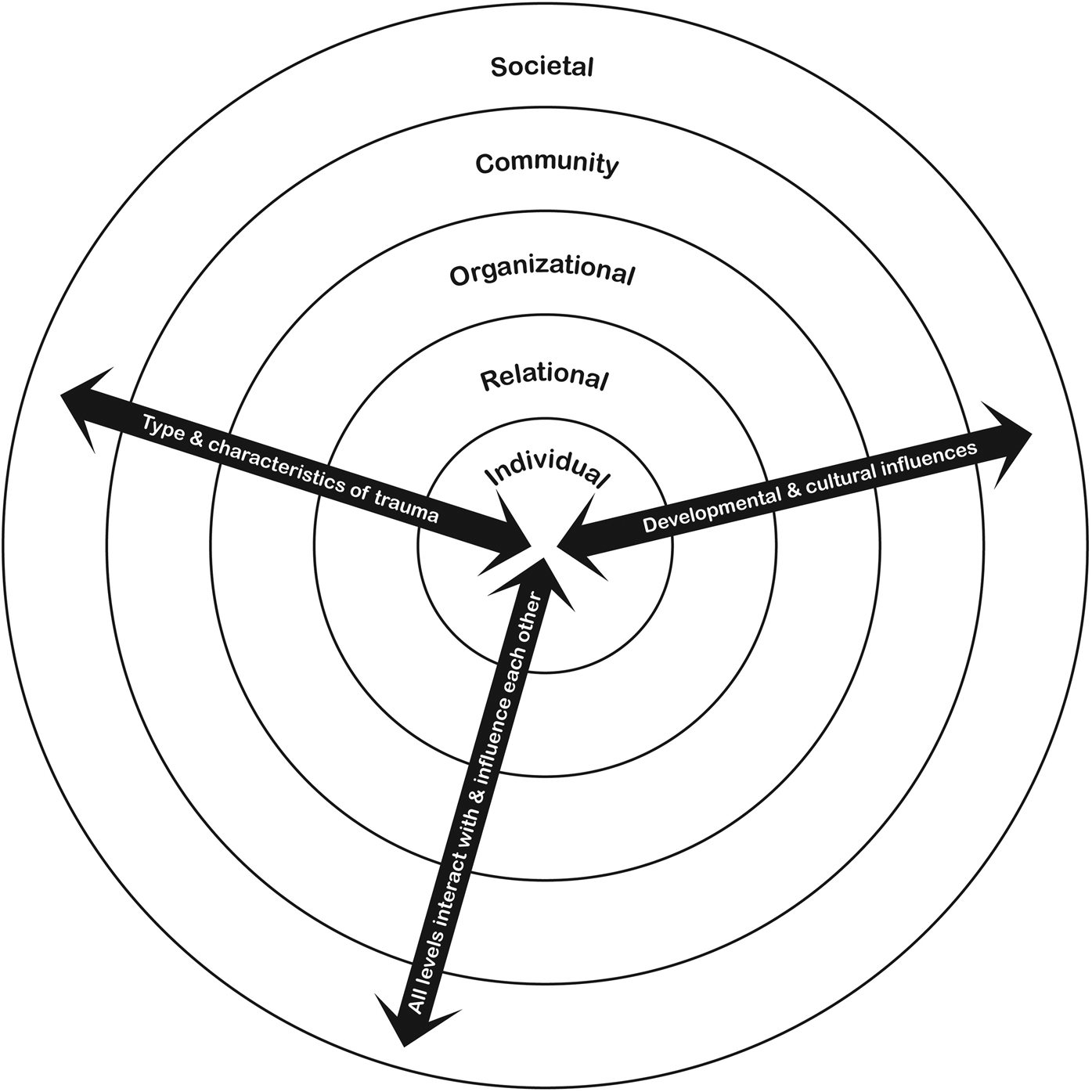

The social-environmental model views public health problems as the result of “the consequence of reciprocal causation unfolding at multiple individual and environmental levels of influence” (Richard et al. Reference Richard, Gauvin and Raine2011:309; Figure 1). At the individual level, each archaeologist's personal history and current behaviors contribute to perpetuating or disrupting harassment. The relationship level recognizes that each archaeologist's thoughts, beliefs, and actions are influenced by that individual's interactions with other archaeologists. The organizational level recognizes the importance of institutions that provide training, employment, resources, and professional communication in establishing norms of professional behavior. The community level refers to the interactions among those organizations. The society level includes governmental laws, policies, and regulations; economic inequalities among individuals, organizations, and communities; broadly held cultural beliefs, attitudes, and norms; and any other wide-reaching factors that that “help create a climate in which [harassment] is encouraged or inhibited” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019).

Figure 1. A trauma-informed, social-environmental model of public health. Adapted from Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT-US] 2014:15. (Graphic by Katie Johnson-Noggle.)

Like the social-environmental model, trauma-informed approaches are evidence-based intervention models aimed at addressing discrimination, harassment, and sexual violence within a public health framework. Trauma-informed approaches first developed over 40 years ago in early rape crisis centers, domestic violence movements, and survivor networks. They have been validated by public health research, and they are now the widely adopted standard endorsed by medical and legal professional communities as well as by government health agencies (National Sexual Assault Coalition Resource Sharing Project and National Sexual Violence Resource Center [NSACRSP/NSVRC] 2017:5; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Organization [SAMHSA] 2014:5).

Trauma is a response that “results from an event, series of events or set of circumstances that is experienced . . . as physically or emotionally harmful” (SAMHSA 2014:7). Trauma begins when an event or experience overwhelms an individual's or a group's normal coping mechanisms (NSACRSP/NSVRC 2017:5). Primary trauma occurs when the traumatizing event is experienced directly by the individual or group; secondary trauma occurs among individuals or groups who witness traumatic events or who are supporting traumatized members of their community. Additionally, trauma is multiscalar: “Traumas can affect individuals, families, groups, communities, specific cultures, and generations” (CSAT-US 2014:7).

A trauma-informed approach is built on three core principles. First, an individual or group is more likely than not to have a history of trauma. We now know that harassment and sexual assault occur at epidemic rates in archaeology. Additionally, archaeologists, as members of a broader society, are exposed to harassment, sexual assault, and other forms of trauma in other aspects of their daily lives. Because most archaeologists have likely experienced or witnessed harassment, “We don't necessarily need to question people about their experiences; rather, we should just assume that they may have this history, and act accordingly” (Tello Reference Tello2018).

Second, without deliberate intervention, social attitudes and “business as usual” organizational procedures can inadvertently retraumatize those who have been affected by harassment. Retraumatization is “any situation or environment that resembles an individual's trauma literally or symbolically, which then triggers difficult feelings and reactions associated with the original trauma” (University at Buffalo—Buffalo Center for Social Research 2021). Examples of this include whenever survivors’ accounts of trauma are trivialized or dismissed, whenever survivors have little or no control over details of their professional lives, whenever trust is broken through a breach of confidentiality and lack of transparency, and whenever reporting harassment increases vulnerability to retaliation (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2019; ASWG 2019:18; CSAT-US 2014:17; Wright Reference Wright, Zimmerman, Vitelli and Hollowell-Zimmer2003:230).

Third, individual and group actions can promote environments of healing and recovery.

Evidence-based responses that support rather than retraumatize survivors and their allies include

(1) Empowering survivors and other vulnerable members of our professional community as resourceful archaeologists who have met the immediate and enduring effects of trauma and risk with creativity, self-preservation, and determination (CSAT-US 2014:3).

(2) Affirming a fundamental commitment to promoting physical and emotional safety in archaeology: “Creating safety is not about getting it right all the time; it's about how consistently and forthrightly you handle situations. . . . Honest and compassionate communication that conveys a sense of handling the situation together generates safety” (CSAT-US 2014:20).

(3) Generating relations of trust through consistent and transparent procedures related to reporting and adjudicating claims of harassment (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:6). In particular, it is essential that survivors’ self-determination, privacy, and right to disengage be honored.

(4) Developing and implementing anti-harassment programs in collaboration with archaeologists who are survivors of harassment, because “survivors are the experts in what is best for them” (NSACRSP/NSVRC 2017:9, 24).

(5) Building cultural competency to ensure that anti-harassment programs support inclusion and avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes, as well as collaborating with nonarchaeological organizations and experts to enhance existing resources.

In this way, trauma-informed approaches extend the effectiveness of the social-environmental model by recognizing that survivors’ experience, knowledge, and creativity are essential resources in addressing harassment. The value of a trauma-informed, social-environmental approach was demonstrated in 2019, when professor emeritus David Yesner registered on-site at the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) Annual Meeting in New Mexico. Yesner had been banned from the University of Alaska Anchorage because of credible sexual misconduct claims filed by nine women, and three of Yesner's victims were already in attendance at the conference.

Initially, the SAA's response to reports of Yesner's attendance demonstrated the potential for “business as usual” organizational responses to be retraumatizing by using “what many have described as ‘gaslighting’ and ‘victim-blaming’ language” (ASWG 2019:17). One SAA tweet rebuked the University of Alaska Anchorage for not notifying the SAA of Yesner's history. SAA leadership also blocked Twitter accounts from members who were critical of the organization's response. As one survivor protested,

@SAAorg chose to side with a sexual predator who has been privately investigated and all nine of us found credible. Three of us were here. You found a retired sick old man more important than three young women just starting out and we are pissed. I won't go quietly away. #saa2019 [Norma Johnson, quoted in Rivera Reference Johnson2019].

Survivors and their allies responded to Yesner's presence and to the SAA's responses through survivor-led, multilevel interventions. They reported their concerns through formal channels and social media (individual level). They organized a buddy system to help vulnerable attendees move safely throughout the venue; organized peer-led support groups for retraumatized attendees; and communicated with other attendees through social media, printed signs, and announcements at conference sessions (relationship level). They also launched an open letter campaign (organizational level), recruited statements of support from leaders of SAA interest groups and other archaeological societies (community level), and collaborated with journalists to generate public awareness of the situation (societal level). Following the conference, survivors and allies took even more actions at all of these levels (ASWG 2019; Blackmore and Rutecki Reference Blackmore and Rutecki2019; Collective Change 2019; Flaherty Reference Flaherty2019; Grens Reference Grens2019; Hays-Gilpin et al. Reference Hays-Gilpin, Thies-Sauder, Jalbert, Heath-Stout, Thakar, Aitchison, Driver, Supernant and VanDerwarker2019; Killgrove Reference Killgrove2019; Klembara and Markert Reference Klembara and Markert2019; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2019; Rivera Reference Rivera2019; Wade Reference Wade2019).

These multilevel, trauma-informed interventions successfully pressured SAA leadership to change their tone, reinstate blocked Twitter accounts, issue formal apologies, refund the conference fees paid by Yesner's victims, and acknowledge serious shortcomings in the SAA's policies and procedures. Also in response to pressure from survivors and their allies, in May 2019, the SAA formed a Task Force on Sexual and Anti-Harassment Policies and Procedures. The following year, it authorized two standing committees: (1) the Meeting Safety Committee, charged with organizing proactive measures to support conference attendees’ safety, and (2) the Findings Verification Committee, which will respond to reports that an SAA member has been found responsible for harassment (Hays-Gilpin et al. Reference Hays-Gilpin, Thies-Sauder, Jalbert, Heath-Stout, Thakar, Aitchison, Driver, Supernant and VanDerwarker2019:9; see also SAA 2020a). Beyond the SAA, other archaeology organizations were also inspired to develop more effective policies and procedures as a result of these interventions, expanding the impact of survivor-led actions to the community level.

Interventions for Disrupting Cultures of Harassment in Archaeology

First, what have you done in relation to the pervasive and endemic physical and structural violences that occur in your discipline? . . . Second, what are you going to do now that your friends, colleagues, and students have articulated so clearly their concerns, hurt, and violations? How do you heal? How do you hold people or yourself accountable? How do you incite change? What is your path (or our discipline's collective path) toward redemption? [Collective Change 2019:13]

Societal Level: Defining Harassment as Scientific and Professional Misconduct

Harassment in archaeology and in related STEMM (science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine) fields is too often treated as an interpersonal matter. Since the mid-2010s, legislators, agency archaeologists, and professional societies have been engaged in a broad coalition to define harassment as scientific and professional misconduct because

such conduct causes harm to, interferes with, or sabotages scientific activity and careers. Sexual harassment and assault creates a hostile environment that reduces the quality, integrity, and pace of the advancement of science by marginalizing individuals and communities. It also damages productivity and career advancement, and prevents the healthy exchange of ideas [Southeastern Archaeological Conference (SEAC) 2018:1; see also Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014].

Classifying harassment as scientific and professional misconduct establishes that harassment is as injurious to the public trust as plagiarism, falsifying data, looting and trafficking in antiquities, coercive citations, and fraudulent use of research funds. First introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2016, the Sexual Harassment in Science Act would, if passed, elevate harassment to the level of unethical conduct for federal purposes and would require any college and university receiving federal grants to publicly report all substantiated findings of sexual assault and harassment by instructors and principle investigators (Johnson Reference Johnson2019; Speier Reference Speier2016). Although the bill has yet to be put to a vote, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has already issued regulations mirroring the proposed legislation (Córdova Reference Córdova2018:NSF Notice 144), as have some archaeological societies.

By defining harassment as scientific misconduct, archaeologists also can take steps to ensure that we are not enabling harassers through our professional relationships: “Every paper they publish, talk they give, and conference they attend enhances the influence they have abused” (Wood Reference Wood2015). As Bhalla (Reference Bhalla2018) urges, “Erode the status that some serial harassers continue to enjoy. Do not collaborate with them. Do not invite them to meetings, to give seminars, etc. Do not invite them to be a PI [principal investigator] on a training grant or to participate in a graduate program.” In an essay titled “What to Do with the Predator in Your Bibliography,” Souleles (Reference Souleles2020) recommends specific measures to avoid elevating the status of harassers through citations: acknowledge the abuse that occurred during cited research, consider alternatives to citing the abuser, and work to move the field beyond the abuser's contributions.

Community and Organization Levels

An organization is any entity that connects people and resources in relation to a goal or mission. Consequently, an archaeological organization can be as small as a five-student college archaeology club or as large as a professional organization such as the SAA (in 2020, about 7,500 members [SAA 2020b]). Organizations can be horizontally networked (as in connections among professional associations) or vertically nested (such as a lab in a research facility, a department in a university, or a regional office of a company). These interorganizational relationships constitute the community level of the social-environmental model.

Organizations generate the contexts in which workplace and educational harassment occurs. Organizations also determine the degree to which harassers will be formally held accountable for their actions and what resources, if any, will be available to support survivors and protect them from retaliation. Consequently, “the most potent predictor of sexual harassment is organizational climate—the degree to which those in the organization perceive that sexual harassment is or is not tolerated” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:x).

Advocacy by both leaders and members is critical to transforming organizational culture and adopting best practices for preventing harassment, supporting survivors, and holding harassers accountable for their actions. The remainder of this section outlines evidence-based approaches that serve as guidelines for archaeological organizations seeking to address harassment, with special attention at the conclusion of the section to archaeological field research contexts.

Empowerment of Survivors and Vulnerable Members

Survivors of harassment and other vulnerable members will know what or who the problems are, why harassment persists in the organization, and what can be done to stop it. Organizations can sponsor forums and listening sessions to bridge individual experience to the organization level and make visible the shortcomings of the organization's policies and procedures (Collective Change 2019:13).

Climate Surveys

Regular surveys are necessary to identify the scope and impact of harassment as well as evaluate whether organization-level interventions are effective in reducing harassment, improving reporting, and supporting survivors.

Codes of Conduct with Resources and Sanctions

Unlike policy statements, organizational codes of conduct have a clear and demonstrable impact in reducing harassment and sexual assault because they specify clear consequences for misconduct (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2020; Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017). Codes of conduct should apply not only to regular members of an organization but also to visitors and subcontractors. The code of conduct and related communications should “convey that reporting sexual harassment is an honorable and courageous action” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:7) that maintains the integrity of the organization. Codes of conduct should also clearly state that retaliation against those who report harassment will not be tolerated.

Effective codes of conduct have “mechanisms to hold members of the community and the leadership—at every level—accountable for meeting behavioral and cultural expectations” (Collective Change 2019:14; see also Aurora and Gardiner Reference Aurora and Gardiner2019). Too often the actions that organizations take against harassers look like rewards:

If there is an outcome to a report of harassment, victims may see their violators “punished” with sabbatical-like leaves (with relief from teaching and service but no curtailment of their research), career advancement at another university, or early retirement with full benefits [Marín-Spiotta et al. Reference Marín-Spiotta, Schneider and Holmes2016].

True sanctions are appropriate in relation to the severity of the code of conduct violation, and they could include restricting activities in the organization; suspending or terminating membership, employment, or enrollment; rescinding awards or honors; and amending or retracting research publications and reports to clearly note misconduct that occurred during research activity. Organizations might also require verified harassers to complete training programs as part of a reentry plan, but training itself should never be used as a substitute for appropriate sanctions.

Clear and Effective Reporting and Adjudication Procedures

Frequently, harassers are in a position of power over their targets, so chain-of-command reporting increases targets’ vulnerability. Race, class, nationality, immigration status, physical ability, and gender and sexual identities further complicate the ability of targets to safely report their experiences. Consequently, it is important to create multiple points of contact, including contact people with a variety of identities and some who are outside the organization chart, such as an ombudsperson or a designated outside officer (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019:336). Information about how to report harassment needs to be clearly visible to all members, especially students and entry-level professionals. These measures help ensure that any archaeologist targeted by harassment can “feel comfortable reporting to a concerned and empowered entity” (Radde Reference Radde2018:251).

Because targets of harassment are often reluctant to report, organizations can also develop disclosure procedures through which a target or bystander can anonymously alert the organization to a violation of its code of conduct without triggering a full report and investigation. This provides another way for the organization to take actions to protect its members. Along with formal pathways to disclosure, organizations can be attentive to informal disclosures made through posts on social media, websites, or other forums.

Training and Education Focused on Behavior, Not Beliefs, That Is Required and Recurrent

Because attitudes and behaviors that contribute to harassment are often supported on a societal level, continual training is needed within every archaeological organization to help members recognize, intervene in, and report harassing behavior. Education should be required of all members at the point of entry to the organization, with specialized training for early career archaeologists, officeholders, instructors, supervisors, and archaeologists in public-facing positions. Organization-level training is most effective when it focuses on “changing behavior, not on changing beliefs” and “on clearly communicating behavioral expectations [and] specifying consequences for failing to meet these expectations” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:5). Training that “combine[s] anti-harassment efforts with civility-promotion programs” provides members with skills to “interrupt and intervene when inappropriate behavior occurs” (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Widnall and Benya2018:5).

Diffusing the Gatekeeper Effect

Archaeological organizations can diffuse the hierarchical relationships created by gatekeepers by restructuring their operations so that no single individual holds direct power over other archaeologists. For example, education programs can institute coadvising, and companies can shift to team-based supervision. Rather than vesting research-permit or collections-access decisions in a single archaeologist, an agency or museum could establish a staff committee to review applications. Whether decision-making authority is held by a single individual or shared, transparent procedures and criteria—with processes for appeal—are important to deter gatekeepers from abusing the authority of their position.

Community-Level Coordination

Vertical and horizontal resource sharing among organizations helps reduce costs and share practical experience while also establishing consistent standards throughout the discipline. For example, SEAC (2019) has developed template codes of conduct for professional meetings and field projects, as well as brochures and training modules that can be adapted for specific projects, divisions, labs, and classrooms. In the United Kingdom, the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (2020) has joined forces with a charitable organization to provide CRM archaeologists with access to training resources, confidential reporting channels, and qualified lawyers.

Organizations can also leverage their resources to support positive change in other organizations. For example, for nearly 40 years, the American Anthropological Association (AAA) has used its role as an opportunity advertiser to incentivize equity and inclusivity (Levine Reference Levine, Nelson, Nelson and Wylie1994:23). Since 2018, the AAA requires that all field schools and other research experiences advertised on AAA media “make available on demand a code of conduct prohibiting sexual assault and sexual harassment” and attest that there are “appropriate reporting mechanisms for those who do experience or witness sexual harassment or sexual assault” (AAA 2020). In 2019, the Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA), the SAA, and the American Institute of Archaeology (AIA) adopted similar policies.Footnote 2

Field Projects as Special Organizations in Archaeology

Because field projects are “highly social experience[s] in which people have to live together and co-operate as part of a group” (Moser Reference Moser2007:246–247), they pose specific challenges to preventing and reporting harassment. The limited resources and time available for field research may lead to “prioritization of data-generation [that] has the potential to contribute to the neglect—benign or otherwise—of team dynamics, such that alienation, harassment, and assault may occur” (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014:1). Because field experience is necessary for archaeological training, and because field experiences often involve costly financial and logistical arrangements (Heath-Stout and Hannigan Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020), participants may be additionally incentivized to endure adverse conditions rather than leave or report harassment.

Despite these challenges, preventing harassment in archaeological field projects is an utmost priority if archaeology, as a discipline, is to move beyond a widespread culture of harassment. As Colaninno and colleagues state,

Aspiring archaeologists may experience their first occurrence of sexual harassment, assault, and violence as undergraduate or graduate students enrolled at field school. . . . It may also be the first time a student's concerns and reports of harassment and assault are intentionally ignored or overlooked. Furthermore, future perpetrators of harassment may see that sexual harassment and assault are normal components of archaeological fieldwork, thereby perpetuating this culture of tolerance [Reference Colaninno, Lambert, Beahm and Drexler2020:112, 114].

In the past two years, several published guides (Colaninno et al. Reference Colaninno, Lambert, Beahm and Drexler2020; Hanes and Walters Reference Hanes and Walters2020; SEAC 2019; Walter and Bergstrom Reference Walter and Bergstrom2020) and a nonprofit training program (Fieldwork Initiative 2020) have been developed to support field project directors and participants in preventing harassment and supporting the well-being of all participants. These, along with the findings of research studies focused on field contexts (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2020; Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017; Radde Reference Radde2018), emphasize that codes of conduct prohibiting harassment—with clear mechanisms of enforcement—are the single most important factor influencing harassment in field research contexts. Codes of conduct are most effective when distributed in advance of the project and reinforced through in-person training (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2020). It is particularly critical to have a contact list for immediate reporting and intervention outside of the principal investigator and project directors (AIA 2019:1–3; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019:336; Radde Reference Radde2018:250). Bradford and Crema (Reference Bradford and Crema2020) found that the frequency of harassment on field projects was correlated with the length of the project. Consequently, longer projects should include refresher trainings. Colaninno and colleagues (Reference Colaninno, Lambert, Beahm and Drexler2020:117) recommend weekly confidential surveys of all project members, as well as facilitated group reflections on project culture, so that project leadership can readily address problems as they emerge.

Codes of conduct for residential archaeology projects need to address personal as well as professional behavior. Discriminatory banter creates an environment of “hostility, aggression, and intolerance toward difference” (anonymous survey respondent, as quoted in Radde Reference Radde2018:246) and should be prohibited at all times. Fraternization is especially perilous during fieldwork, and the AIA (2019:2) recommends absolute prohibition of “relationships between anyone in a supervisory role and anyone else in a role to be supervised.” Clear rules around alcohol consumption are necessary to prevent the development of a “party culture” that allows harassers to evade responsibility (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; see also Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020). Colaninno and colleagues (Reference Colaninno, Lambert, Beahm and Drexler2020:118) recommend that because of “the known link between substance use and sexually inappropriate behavior . . . the discipline must call on field directors to implement alcohol- and drug-free field schools among residential programs.” Field-project codes of conduct should also emphasize that a participant's choices around drugs or alcohol in no way excuse the actions of a perpetrator or put a victim at fault.

Transportation, housing, and communication pose specific challenges for ensuring participants’ well-being on residential archaeology projects. Because field sites are often remote, “students have the potential to feel stuck with their harasser/abuser, which can foster a more immediate fear of bodily harm and mental anxiety” (Hanes and Walters Reference Hanes and Walters2020:9). The feeling of remoteness and of being cut off from preexisting social networks can occur whether the project is domestic or international. Ensuring that participants can communicate with people outside the field project—especially with off-site confidential services and reporting offices—is critical, as is guaranteeing that all participants have access to safe transportation should they wish to leave the project. Providing advance information about housing arrangements, respecting participants’ gender identities, and avoiding using “presumed heterosexual gender roles” when assigning field housing all contribute to safer conditions (Blackmore et al. Reference Blackmore, Drane, Baldwin and Ellis2016:22; see also Dylla et al. Reference Dylla, Ketchum and McDavid2016; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019:336). When planning for field projects, consider the possibility that if a claim of harassment or sexual assault is made, it may be necessary to provide both the reporter and the accused with separate, safe living spaces during and after the investigation; fee refunds or paid leave; and safe transportation home (Hanes and Walters Reference Hanes and Walters2020:9).

Relationship Level

Transforming our disciplinary culture also requires positive actions in our professional relationships. One of the most important relational interventions is to speak openly and frankly to other archaeologists about harassment. We can emphasize our admiration and support of survivors and bystanders who report harassment. In this way, “bad behavior is vilified and victims are supported to take action if they choose” (Radde Reference Radde2018:250). It is also important to amplify the autonomy and agency of survivors by not only supporting their advocacy for themselves and others but also respecting their needs for privacy and disengagement.

Because archaeological culture has historically prized informality in professional relationships (Leighton Reference Leighton2020; Moser Reference Moser2007), we archaeologists may feel uncomfortable acknowledging that we occupy supervisory and gatekeeping roles. Whatever our position, acknowledging power differentials in our professional relationships is essential to disrupting cultures of harassment in archaeology. It is especially important to remember that subordinates are not able to consent freely to personal and intimate overtures from instructors, supervisors, and gatekeepers. Supervisors and gatekeepers may, at times, misinterpret a subordinate's role-appropriate behavior (professional respect, attention, and deference) as personal interest. Regardless of the subordinate's actions, it is always the responsibility of the supervisor or gatekeeper to maintain clear professional boundaries.

A trauma-informed approach helps us understand that clear boundaries in our professional relationships support an inclusive and supportive disciplinary culture. For example, when I was a student and entry-level archaeologist, it was very common for me to be invited to supervisors’ homes or to bars for after-hours one-on-one meetings. As I rose through the ranks, I issued similar invitations to staff and students. Unfortunately, this common practice has given cover to harassers who use “friendly” invitations to groom prospective targets. Here is one example:

On our way back to town, Amanda asked me to come home with her. In her living room I became unsure of her intentions. . . . She was my adviser. I could not afford to guess wrong, to act wrong, so I froze [She 2000:170].

Adopting a more formal approach to professional interactions need not negatively impact the collegiality that many archaeologists prize—in fact, it may enhance our disciplinary culture by fostering a more inclusive environment.

The relationship level is especially important in supporting junior colleagues and peers who are targeted by harassment. Many senior archaeologists, including me, were trained to endure rather than challenge harassment. By adopting a trauma-informed perspective, we can respond to disclosures of harassment by empowering survivors to take the actions that they feel best support their own well-being.

Individual Level

Interventions at the relational, organizational, community, and societal levels focus on behavior rather than beliefs. On the individual level, a value-centered approach generates core principles that can guide individual conduct (Hays-Gilpin et al. Reference Hays-Gilpin, Thies-Sauder, Jalbert, Heath-Stout, Thakar, Aitchison, Driver, Supernant and VanDerwarker2019:9; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017:718). Often, this begins with self-reflection: What does being an archaeologist mean to me? What do I value about being part of this professional community? What are the values that I bring to archaeology from my personal background and nonprofessional communities?

Connecting with core values helps archaeologists navigate situations in which our own self-interest may conflict with promoting a harassment-free environment. For example, on one project that I directed, three participants reported to me that they felt uncomfortable because of looks and comments from a gatekeeper who frequently visited the project. I also had been uncomfortable with this person's behavior, but I was afraid that confronting the gatekeeper could put the project in jeopardy. So, I brushed off the participants’ complaints, telling them I did not see any evidence of a real problem.

If instead I had connected with my core values—a commitment to honesty and the right of every archaeologist to learn and work in a safe and inclusive environment—I might have responded differently. I could have contacted a mentor for advice. I could have acknowledged the conflict of interest and connected with outside resources, such as human resources or Title IX offices, that could have brought more impartial perspectives. Or I might have spoken directly with the gatekeeper about how his behavior was affecting the team.

When I reflect on my career, I see clearly that I often believed I was individually powerless to change the culture of harassment in archaeology. Many of us have experienced being unable to stop harassment from happening to us and to other archaeologists. Many of us bravely reported harassment and then found that nothing was done to protect us or to hold our perpetrators accountable. Over time, these experiences can erode our sense of agency.

A trauma-informed approach helps us understand that our initial feelings of powerlessness are normal responses to abnormal situations. These and other coping strategies may have helped us to survive difficult circumstances and enabled us to persevere in archaeology. Reflecting on our core values allows us to acknowledge our creativity and resilience and apply these values to disrupting harassment in archaeology.

As archaeologists, we can empower ourselves individually by preparing in advance to address harassment if it occurs. A personal checklist might include (1) knowing how to contact confidential resources for support; (2) learning about channels for formal reporting; (3) establishing a communication plan with a trusted friend or colleague outside the workplace, education program, or field site; (4) requesting codes of conduct and information about communication resources, transportation, and (for residential projects) lodging; and (5) identifying personal boundaries related to personal information, alcohol and drug use, and social interactions outside of project or work hours.

Archaeologists can further amplify these strengths by seeking training and mentorship “in the interpersonal skills of conflict management, negotiation, and resolution that would allow them to informally and formally confront personnel issues as they arise and before they can escalate” (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014:1). As bystanders, we can intervene if we witness harassment by directly addressing the harasser: “Whoa, back off!” “Not OK!” “Let's drop that kind of talk.” “[That behavior] is not supported by our code of conduct; you need to stop” (Bhalla Reference Bhalla2018; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019; Lavery Reference Lavery2014; SAA 2015). Comments like these disrupt harassment by redirecting the harasser's attention away from the target and toward our interruption. They can also help shift the target's experience “from feelings of powerlessness and isolation to those of support and justification” (Lavery Reference Lavery2014).

Conclusion

Harassment has shaped our discipline at a fundamental level, affecting who can practice archaeology; how archaeologists are trained; what research topics are investigated; and how archaeological data is interpreted, published, and cited. Although studies conducted in the past 10 years have documented the extent of the problem, there still is much more work to do. The experiences of nonbinary archaeologists, archaeologists of color, LGBTQIA+ archaeologists, and archaeologists with disabilities are vastly understudied. Targeted research is needed to ensure that the experiences of already marginalized archaeologists are not further neglected.

In the past five years, many archaeological organizations have initiated new policies and procedures intended to prevent harassment. These interventions are most likely to succeed when they are developed in collaboration with survivors and other vulnerable archaeologists, and when they leverage organizational resources to support change on multiple levels of the social-environmental model. We need to view this as an ongoing process: regular climate surveys along with mechanisms for ongoing feedback are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of specific interventions.

Social-environmental models and trauma-informed approaches are transformative because they help us see that all archaeologists have the ability to disrupt cultures of harassment in archaeology. Most archaeologists deeply value our shared discipline and our relationships with each other. These core values are our collective strength. Together, we can disrupt intergenerational cycles of harassment and create a more inclusive archaeology.

Coda: Where to Go for Support

It can be overwhelming to learn about the pervasiveness of harassment in archaeology. For survivors and witnesses, it can be both validating and unsettling to learn that these negative experiences are part of a discipline-wide pattern. Whether you yourself are a survivor or whether you have—or someone you know has—witnessed harassment and sexual assault, you are not alone. Support is available. If you are not sure where to start, the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) provides free and confidential support to survivors and to those who care about them. Support is available 24 hours per day, 7 days per week by phone (800-656-4673) and via live chat at https://www.rainn.org/. En español, llame al (800-656-4673) a la Línea de Ayuda Nacional Online de Asalto Sexual o comuníquese a través de la opción “Chat Ahora”: https://www.rainn.org/es.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to all survivors of harassment in archaeology. I am especially thankful to those who have conducted research on harassment in archaeology and to activists and advocates throughout archaeology's history. I began to write this article series during my involvement in anti-harassment committees and programs in my workplace. My thanks to many colleagues, students, staff, and administrators—too numerous to list by name here—who shared their expertise and experiences, and to Danielle J. Bradford, Kathryn Clancy, Deb Cohler, Carol Colaninno, Kathy Coll, Maura Finkelstein, Kelley Hays-Gilpin, Mark Hauser, Laura Heath-Stout, Lochlann Jain, Caren Kaplan, Kristina Killgrove, Hugh D. Radde, Doug Rocks-Macqueen, Maureen S. Meyers, Sarah Rowe, Dawn Rutecki, Megan Thies-Sauder, Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof, and seven anonymous reviewers who provided thoughtful feedback on earlier drafts. Special thanks to Lynn Gamble for her support and editorial guidance, Laura Daly for copyediting, Katie Johnson-Noggle for graphic design, and Grace Alexandrino Ocaña for the Spanish translation of the abstract. The Stanford Archaeology Center Director's Fund generously funded Gold Open Access for this article.

The author is not aware of any financial interests or affiliations that pose a conflict of interest with the content of this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study is based on analysis of published research, survivor accounts, news reports, and online resources. All data is available through the sources listed in the References Cited section.