Executive leaders in public organisations often face the decision to take, delegate, or cede responsibility for certain policy issues and specific programmes and interventions. These decisions become even more salient amid crises given that these situations often require a higher degree of flexibility, cooperation, and interorganisational coordination to achieve an effective response (Comfort and Kapucu Reference Comfort and Kapucu2006). Arguably, migration had been one of the top worldwide policy concerns during the last decade until the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, “[m]igration is now a top-tier political issue interconnected to human rights, development, and geopolitics at national, regional and international levels” (International Organization for Migration 2019). Therefore, understanding policy uptake decisions under migrant crises allows scholars and practitioners to identify the drivers of decisionmaking in complex situations with deep social, economic, and political implications.

Decision-making processes are affected by individual-level features, such as knowledge, memory, experience, motives, ethics, and attitudes (Anderson Reference Anderson1993; Gobet and Simon Reference Gobet and Simon2000; Johnson-Laird Reference Johnson-Laird, Manktelow and Chung2004), external pressures (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore2004; Lavi-Faur Reference Lavi-Faur2005), control powers (Page Reference Page2012; Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2017), and information processing (Thurmaier Reference Thurmaier1992). Moreover, decisionmakers’ symbolic and normative concerns (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1976), cognitive shortcuts due to actors’ bounded rationality (Weyland Reference Weyland2007; Hong Reference Hong2019), and decision difficulty (Landsbergen et al. Reference Landsbergen, Bozeman and Bretschneider1992) also shape the decision-making process. Given the difficulty and complexity of crises; consequently, shortcuts, biases, and emotions become more salient for decisionmaking under such strenuous situations (Sayegh et al. Reference Sayegh, Anthony and Perrewé2004; Ballesteros and Kunreuther Reference Ballesteros and Kunreuther2018).

This study presents a survey experiment with incumbent Colombian mayors to test the role of credit-claiming opportunities on chief executives’ preferences for project uptake during a sustained migrant crisis. Colombia currently hosts about 1.5 million Venezuelan migrants who have fled their country amid an acute socio-economic and political crisis in the past five years (International Organization for Migration 2019). A face-to-face survey instrument asked mayors whether they would take or relinquish to upper levels of government (subnational and national) either formulation and/or implementation of a social project benefiting Venezuelan migrants. We manipulated two contextual dimensions expected to offer different credit-claiming incentives: (i) project visibility (classroom construction versus vaccination program) and (ii) salience of beneficiaries (i.e. whether the beneficiaries are related to the mayors’ constituents). We expect mayors are more likely to take on the project when it is more visible (classrooms), and the beneficiaries are more salient. Additionally, we expect more mayors to prefer taking on the project’s implementation than its formulation.

In intergovernmental relations, policy uptake decisions occur within processes of institutional change. Thus, the decentralisation phenomenon that most countries have experienced during the past four decades has led to a substantial delegation of power, resources, and responsibilities from national to subnational and local governments (Falleti Reference Falleti2010; Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks, Schakel, Osterkatz, Niedzwiecki and Shair-Rosenfield2016). In this context, the extent and scope of mayoral decision-making autonomy have become a contentious issue. For instance, studies on autonomy and decentralisation have highlighted the importance of civil society and local accountability to avoid elite capture and corruption (Bardhan and Mookerjhee Reference Bardhan and Mookherjee1999; Bardhan Reference Bardhan2002; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Lin and Treisman2009).

Most research exploring decisions to take or cede policy responsibility operates in delegation contexts where delegators keep ex-ante and/or ex-post controls over the delegees’ decisions (McCubbins et al. Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987, Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989; Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002). Yet, mayoral decisionmaking to relinquish autonomy towards upper-level governments presents a unique context to explore policy uptake decisions because mayors would hold no control powers over the central government as delegees. In explaining their preference to take on a policy project, we argue mayors consider their perceived opportunities for ex-post credit claiming and personal gains – e.g. reputation, promotion, political prospects – against their perceived risk of facing ex-post blaming costs – e.g. protests, impeachment, political capital loss. In calculating these tradeoffs, contextual decision characteristics act as levers to shift the balance between perceived credit-claiming opportunities and blame-acceptance risks.

Results suggest neither issue visibility (classroom construction versus vaccine program) nor salience of beneficiaries has a significant effect on mayoral uptake preference for project formulation. However, issue visibility significantly affects mayoral uptake preferences for project implementation. Specifically, when presented with a classroom construction project, rather than a vaccination project, mayors are statistically and significantly less likely to cede project implementation to the national government. Moreover, we find mayors are less likely to cede the joint formulation and implementation phases when the project’s beneficiaries are more salient for their constituents (migrants have relatives in the municipality).

This study contributes to the literature on executive decisionmaking by exploring credit-claiming levers of policy uptake decision in a context where decisionmakers possess no control mechanisms over the actions of the delegees. In addition, this research also contributes to the understanding of intergovernmental relations by studying local executives’ decisionmaking under a prolonged and complex crisis in an institutional setting where local governments acquired autonomy only a generation ago. Studying credit claiming and project uptake in contexts where mayors have gained autonomy becomes relevant, given that several national governments have attempted recentralisation reforms in reaction to local corruption, elite capture, poor performance, and greater national interest in controlling economic growth (Dickovick Reference Dickovick2011; López Murcia Reference López Murcia2022). Moreover, the scarcity of nonprofit organisations as service providers makes municipal decisions essential for addressing local needs. Finally, it is important to highlight that this study adds to the scarce but growing body of research involving experiments with political elites, which more closely resembles real decision-making conditions. The study does so in a seldom explored South American context that exhibits institutional settings not available in advanced Western democracies.

Policy uptake in intergovernmental arrangements

Uptake decisions by politicians

Some researchers understand policy uptake as citizens’ decisions whether to enroll and use certain public programmes, which can be influenced by informational, psychological, and ideological factors (Lerman et al. Reference Lerman, Sadin and Trachtman2017). Yet, others have explored policy uptake from the perspective of electoral competition, focusing on elected officials’ adoption of certain policy issues raised by their opponents during campaigns (Sulkin Reference Sulkin2005, André et al. Reference André, Depauw and Deschouwer2013). In this study, policy uptake corresponds to elected officials’ decisions to take policy issues as their responsibility instead of ceding them to the jurisdiction of another policy actor.

These policy uptake decisions may be subject to the influence of varied factors. From a rational comprehensive approach, one could consider a decision-making process where individuals maximise utility through cost–benefit analyses (Buchanan and Tullock Reference Buchanan and Tullock1962). However, due to bounded rationality (Gilovich et al. Reference Gilovich, Griffin and Kahneman2002; Weyland Reference Weyland2007), decisionmakers may rely on cognitive shortcuts, heuristics, and deliberative thinking (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011). Furthermore, decisionmakers are subject to symbolic and normative concerns (March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1976) that also frame their decision process.

Literature on delegation and the political control of bureaucracy in the United States provides important insights on understanding politicians’ decisionmaking regarding policy uptake or cession. For instance, both the president and Congress are more likely to exercise control and retain decisionmaking when issues are more salient and less complex (Gormley Reference Gormley1986, Ringquist et al. Reference Ringquist, Worsham and Eisner2003, Eshbaugh-Soha Reference Eshbaugh-Soha2006). From a transaction-cost perspective, this might be the result of delegating power when higher levels of information are required (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994, Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002), and delegees lack incentives to deviate from the principal’s preferences. Furthermore, the existence of multiple principals (e.g. legislators and the executive) and their eventual disagreement creates spaces for bureaucratic discretion and greater delegation (Hammond and Knott, Reference Hammond and Knott1996; Oosterwaal et al. Reference Oosterwaal, Payne and Torenvlied2012; Alston et al. Reference Alston, Alston, Mueller and Nonnenmacher2018).

Political principals may impose ex-ante administrative controls when ceding autonomy to bureaucratic agencies (McCubbins et al. Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1987, Reference McCubbins, Noll and Weingast1989). These ex-ante controls allow politicians to narrow the discretion space of delegee bureaucrats. Moreover, both Congress (Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002) and the executive branch (Wiseman Reference Wiseman2009) often retain institutional mechanisms to oversee bureaucratic action, thus influencing policy ex-post. In these settings, political actors retain greater authority over policy formulation and cede a constrained space of autonomy to the bureaucracy for implementation.

Intergovernmental policy uptake in decentralised contexts

Contrary to the case of bureaucratic delegation, mayors are not likely to retain control powers or oversight mechanisms when relinquishing autonomy to an upper level of government. Therefore, this institutional difference may create different incentives for policy uptake. Moreover, bureaucratic autonomy, capacity, and performance vary widely among national organisations (Bersch et al. Reference Bersch, Praça and Taylor2017, McDonnell Reference McDonnell2017) in many parts of the developing world. In turn, lack of local bureaucratic quality and robust organisational support make the mayor’s position something of “a one-man band” (Fiszbein Reference Fiszbein1997) with a substantial role in policy making at the local level. However, the mayor does need approval for her/his initiatives from the local corporation (concejo municipal), which leads to bargaining strategies to gain majoritarian support from the different political parties that make up the city council. Finally, since the position of city manager does not exist, mayors perform both political and administrative functions, and therefore, mayoral decisionmaking must consider both managerial and political implications.

The figure of the elected mayor is relatively new for many developing countries adopting decentralisation over the last 30 or 40 years. The varied institutional paths that shaped the decentralisation process can be understood through the lenses of policy uptake decisionmaking and autonomy. For instance, decentralisation may strengthen local power and autonomy when local interests prevail in the process. However, decentralisation may overburden local governments with more responsibilities than they can manage when the process is directed by the national government (Falleti Reference Falleti2010). In making decisions about intergovernmental policy uptake, therefore, mayors might consider not only fiscal (Bahl and Linn Reference Bahl and Linn1994; Rodden Reference Rodden2006) and administrative constraints but also the potential benefits and risks of accepting or relinquishing autonomy (Weingast Reference Weingast2014).

Explaining policy uptake through contextual levers of credit claiming

Credit claiming and blame avoidance are two of the main drivers of policymakers’ behaviour. Politicians attempt to claim credit when either the perceived costs or benefits of a policy choice are high and concentrated (Weaver Reference Weaver1986a). However, they will aim to avoid blame when both potential benefits and costs of a policy choice are high for distinct segments of the constituency (Weaver Reference Weaver1986a), or when austerity impedes adopting policies that permit credit claiming (Bonoli Reference Bonoli, Bonoli and Natali2012). Moreover, citizens exhibit negative bias when assessing government’s performance information (James and John Reference James and John2007; Olsen Reference Olsen2015; Deslatte Reference Deslatte2020), which may further motivate decisionmakers to avoid blame for negative outcomes than to seek credit for successes (Weaver Reference Weaver1986b; Pierson Reference Pierson1994). In turn, evidence shows that delegation, i.e. politicians not exercising discretion, reduces citizens’ attribution of blame (James et al. Reference James, Jilke, Petersen and Van de Walle2016).

Overall, a chief executive’s decision to cede or retain autonomy can be understood as a cost-benefit analysis in which the expected gains of credit claiming and costs of accepting blame play a significant role. Moreover, while resource availability and issue complexity affect decisions to delegate (Hill and Williams Reference Hill and Williams1993); “[w]here politicians have the incentive, they manage to deal with complexity, and they find the time to do it” (Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1982, 60–61). In the context of intergovernmental policy uptake, subnational political elites often aim to claim credit even for decisions taken at the national level by taking advantage of blurred credit attribution (Nicholson-Crotty and Theobald Reference Nicholson-Crotty and Theobald2011, Rodríguez-Chamussy Reference Rodríguez-Chamussy2015, Cruz and Schneider Reference Cruz and Schneider2017). Moreover, rival subnational governments also may hinder implementation of national policies when credit attribution is clear (Niedzwiecki Reference Niedzwiecki2016). In response, national governments may by-pass rival local governments in policy implementation to impede mayoral credit claiming (Bueno Reference Bueno2018).

Meanwhile, times of crisis might increase the likelihood of decisionmakers to shift blame attribution (Bach and Wegrich Reference Bach and Wegrich2019) and to delegate to new ad hoc actors (Sebok Reference Sebok2015) because organisational leaders may be less likely to steer for meaningful reform amid a crisis (Boin and Hart Reference Boin and Hart2003). Therefore, a perspective of crisis as a process rather than a pointing event (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017) can be useful to understand executives’ policy uptake decisions during a crisis. For instance, voters seem to reward disaster relief activities more highly than mitigation efforts (Healy and Malhotra Reference Healy and Malhotra2009). Furthermore, Bundy and Pfarrer (Reference Bundy and Pfarrer2015) propose that people separate situational attribution (who caused the crisis?) from response strategy when allocating approval, legitimacy, and reputation to an organisation. Consequently, credit claiming may remain a main driver for local chief executives’ decision to act or to cede action to upper levels of government during a crisis. Next, we explore three levers that should modify credit claiming opportunities for mayors, thus shifting their preferences for policy uptake in this context.

Project visibility

Social cognitive theory suggests decisionmakers will concentrate their cognitive capacity on issues they consider most salient (Lavine et al. Reference Lavine, Sullivan, Borgida and Thomsen1996, 297; see also Boninger et al. Reference Boninger, Krosnick, Berent, Fabrigar, Petty and Krosnick1995 and Avellaneda Reference Avellaneda2013). In this view, issue salience acts as a cognitive shortcut through which decisionmakers reduce the informational burden (Tversky and Kahneman Reference Tversky and Kahneman1981). In turn, scholars often consider visibility as a dimension (Kiousis Reference Kiousis2004) or an expression of salience (Hacker Reference Hacker2002; Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007). Visible issues are more likely to become salient in the public policy process and to be considered in agenda setting (Manheim Reference Manheim and McLaughlin1986). Indeed, Gingrich (Reference Gingrich2014) has shown that the visibility of the welfare state is directly associated to the degree to which voters consider social policy positions when voting. Thus, chief executives might perceive more visible issues or projects as better targets for credit claiming, given the weight and attention voters tend to place on them.

Few experimental studies measure issue visibility and provide support for its role on policy uptake decisions. In an experiment with Latin American mayors, Avellaneda (Reference Avellaneda2013) states that even though mayors overall avoid delegation because of the potential autonomy loss, mayors preferred delegating spending authority for less visible issues, such as education, but not for more visible ones like infrastructure issues. Avellaneda (Reference Avellaneda, Meier, Rutherford and Avellaneda2017) also tested the delegation effects of issue visibility through a survey experiment of 143 incumbent Honduran mayors. In this case, mayoral delegation for infrastructural issues fails to differ statistically from mayoral delegation for educational issues. The inconsistent results on the delegation decision effects of issue visibility call for further tests in other policy uptake contexts.

Although perceived visibility may change over time (Price Reference Price1978, 548), in general, infrastructure projects, which produce tangible outputs, are visible thus generating greater incentives for credit claiming. Conversely, despite the important outcomes and impacts a vaccination project can bring about – for example, avoiding an epidemic – its visibility tends to be limited to the time when the vaccine is administered because an effective implementation will cause the disease to fade from view. Indeed, in the Latin American context, the terms “campaña de vacunación” and “jornadas de vacunación” are commonly used to refer to massive but relatively short-lasting – a few weeks – vaccination interventions (see for instance Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social 2019; Pan-American Health Organization 2019). Moreover, in 2019, when this study was conducted, vaccination programs, in general, did not have the level of visibility that they have acquired during the COVID pandemic. Consequently, mayors as decisionmakers are expected to prefer ceding autonomy over vaccination projects rather than infrastructure projects.

In sum, formulation and implementation of more visible projects, such as classroom construction, may offer more credit-claiming opportunities and, in turn, political and reputational benefits to mayors, compared to vaccination projects. Consequently,

H1: Mayors are more likely to take on social projects, instead of ceding them to other levels of government, when confronting more visible issues.

Salience of beneficiaries

Along with project visibility as an expression of salience, we expect the salience of the project’s beneficiaries may also influence executives’ preferences for uptake or relinquishing. Psychology scholars contend that heightening the salience of a particular social identity can influence behaviour, perceptions, and performance (Hinkle and Brown Reference Hinkle, Brown, Abrams and Hogg1990; Hogg Reference Hogg1992; Abrams Reference Abrams1994). Some scholars have offered insights on how these influences may occur. For instance, Forehand et al. (Reference Forehand, Deshpandé and Reed2002) posit that individuals process information that is identity-relevant when a given identity component is activated, thus leading to “identity salience – a state characterised by heightened sensitivity to identity-relevant stimuli” (p. 1086).

Identity salience may in turn play a role in the social construction of a policy’s target populations, which is a highly contingent process that influences people’s policy support and their perceptions about its beneficiaries (Schneider and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). Migrant and refugee populations, for instance, have been subject to either positive (Song Reference Song2013) or negative social construction (Aguirre Reference Aguirre1994), depending on the socio-political context. Also, a closer identification with a particular social group may lead to the public’s perception of a project or policy issue as more proximate. Soss and Schram (Reference Soss and Schram2007) propose proximity as a key dimension to understand policy salience and mass feedback processes given that proximate policies affect “people’s lives in immediate, concrete ways” (p. 121).

Therefore, if mayors value political gains through credit claiming, they should prefer taking over projects whose beneficiaries are more salient to their core constituency. In the case of migration, those migrants who have family connections to the local population are likely to be perceived as more salient and proximate, and to be socially construed in a more positive manner. On the contrary, projects that benefit other populations, for instance migrants without local connections, should be perceived as less valuable in terms of potential credit claiming, and less worthy of risking blame for the project’s costs. Moreover, in settings where constituents’ basic needs are unsatisfied, diverting resources and managerial efforts to benefit nonconstituent groups holds little appeal, encouraging chief executives to relinquish these projects. Consequently,

H2: Mayors are more likely to take on projects serving populations more salient to their constituents, rather than ceding them to other levels of government.

Phase in the policy process

The credit-claiming framework may also be helpful to explain decisionmakers’ preference for project uptake or relinquishing under different phases of the policy process. For instance, formulation and implementation may be perceived differently by the public. In many instances, the implementation phase is the only visible phase, as constituents may have no information about policy formulation (Gormley Reference Gormley1986). While solutions to problems or concerns are offered during policy formulation, the implementation phase materialises what was formulated (Anderson Reference Anderson2011). Policy managers determine whether to focus on outputs or outcomes, and which ones, in the implementation phase (Waters-Robichau and Lynn Reference Waters-Robichau and Lynn2009).

Policy outputs and outcomes are thus the policy components that constituents are more likely to perceive. Therefore, we expect chief executives to place more emphasis on the implementation stage given the increased perceived opportunities for credit claiming due to salience and visibility. For instance, Niedzwiecki (Reference Niedzwiecki2016) showed how Brazilian and Argentinian subnational governments collaborate on the implementation of national social policies when attribution is not clear, and thus they may obtain credit for the policy’s results. Moreover, despite legislators’ efforts to secure strict implementation of adopted legislation, considerable discretion exists in the implementation phase (Keiser and Soss Reference Keiser and Soss1998). In turn, the gap between actions adopted and those implemented is particularly sizeable in developing contexts (Weingast Reference Weingast, Heckman, Nelson and Cabatingan2010). In these contexts, also characterised by low levels of local government capacity, we might expect that mayors focus their limited resources on implementation as the policy phase that allows them more control, visibility, and eventual political gains. Consequently,

H3: Mayors are more likely to take on a project’s implementation, rather than its formulation, instead of ceding it to other levels of government.

Case selection: social service provision in Colombia

The Colombian territory is divided into approximately 1,100 municipalities.Footnote 1 At the next level of aggregation, 32 departamentos – akin to provinces – serve as the intermediate level of government. In each municipality, mayors are the political and administrative executives who lead local governments. Mayors are elected for four-year terms and cannot run for re-election for a consecutive term. Banning executive officials to run for immediate re-election has been a common institutional feature in Colombian politics for the better part of the country’s history, and it is rooted in the aim to tackle corruption and concentration of power (Jaramillo Reference Jaramillo2005). Thus, mayors have never had the opportunity to run for an immediate second term since mayoral elections started in 1988.

Even though these institutional characteristics might discourage incentives for credit claiming, there is evidence that a substantial share of mayors pursue further political career goals and thus are interested in keeping their political capital. Our own analysis finds that 40% of former mayors from the 2012 to 2015 period ran for office in the next electoral cycle. Of all 2012–2015 mayors, 32% ran for mayoral re-election for the 2020–2023 term. Indeed, about a sixth of current mayors and a third of sitting governors are former municipal mayors. Yet, these are underestimations of political ambition as other mayors may pass the political relay to their relatives or close allies, or they might pursue political appointment to nonelected positions. Also, it is not uncommon to see mayors’ relatives and close allies running for office during the mayoral term in the context of high personalisation of local politics in Colombia (Avellaneda and Escobar-Lemmon Reference Avellaneda and Escobar-Lemmon2012). Therefore, it is highly likely that mayors are interested in preserving their political capital for future involvement through their own electoral runs, those of their close allies and relatives, or political appointments.

Although Colombia is a unitary republic, municipalities have enjoyed a substantial degree of autonomy since the 1991 Constitution advanced a process of political, fiscal, and administrative decentralisation (Falleti Reference Falleti2010). Thus, municipal governments not only act as agents of the national government for policy implementation but also oversee several policy areas and play an important role in providing social services. Provision of education and health care is decentralised and usually the responsibility of departamentos. However, certain municipalities are “certified” by the national government to assume the direct administration of service provision (Bello and Espitia Reference Bello and Espitia2011). Moreover, municipal governments often engage in partnerships with their departamentos and the national government to make improvements (e.g. infrastructure or training) to health and education provision. While private schools exist, public provision plays a fundamental role, particularly in small municipalities. For instance, roughly 80% of current students enrolled in primary and secondary education in Colombia attend public schools. Subnational governments also support schools in providing transportation, lunch programs, and pre-enrollment outreach to improve access to the school systems.

The Colombian health care system includes private and public insurers, as well as private and public service providers. Public providers are structured as autonomous public organisations under the oversight of municipal and departamento governments. Often, a public provider is the only one present in small and rural municipalities (Jaramillo Mejía Reference Jaramillo Mejía2016). Moreover, municipalities are responsible for enrolling people eligible for subsidised health insurance and for implementing public health and health prevention policies in their jurisdiction (Ley 100 de 1993).

The study’s incorporation of migrant policy reflects contemporary concerns in Colombia. Migration from Venezuela has become a critical factor for Colombian social policy, as Venezuela has been immersed in a massive socio-economic and political crisis over the past six years (The Economist 2019). As a result, about six million Venezuelans have migrated or sought refuge worldwide (R4V 2022). Colombia, Venezuela’s neighbor with which it shares a 1,378-mile border, hosts about 1 ½ million Venezuelan refugees and has served as a transitory stop for at least another 1 million Venezuelans migrating to the rest of South America (Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Colombia 2019). Thus, Colombia has received what amounts to nearly 5% of its total population as Venezuelan migrants, one of the largest migration waves worldwide. In this challenging context, national and subnational authorities in Colombia have struggled to provide basic services to the migrant population. Specifically, mayors have been outspoken in their demands for more attention, coordination, and resources from upper levels of government.

Survey-experiment design

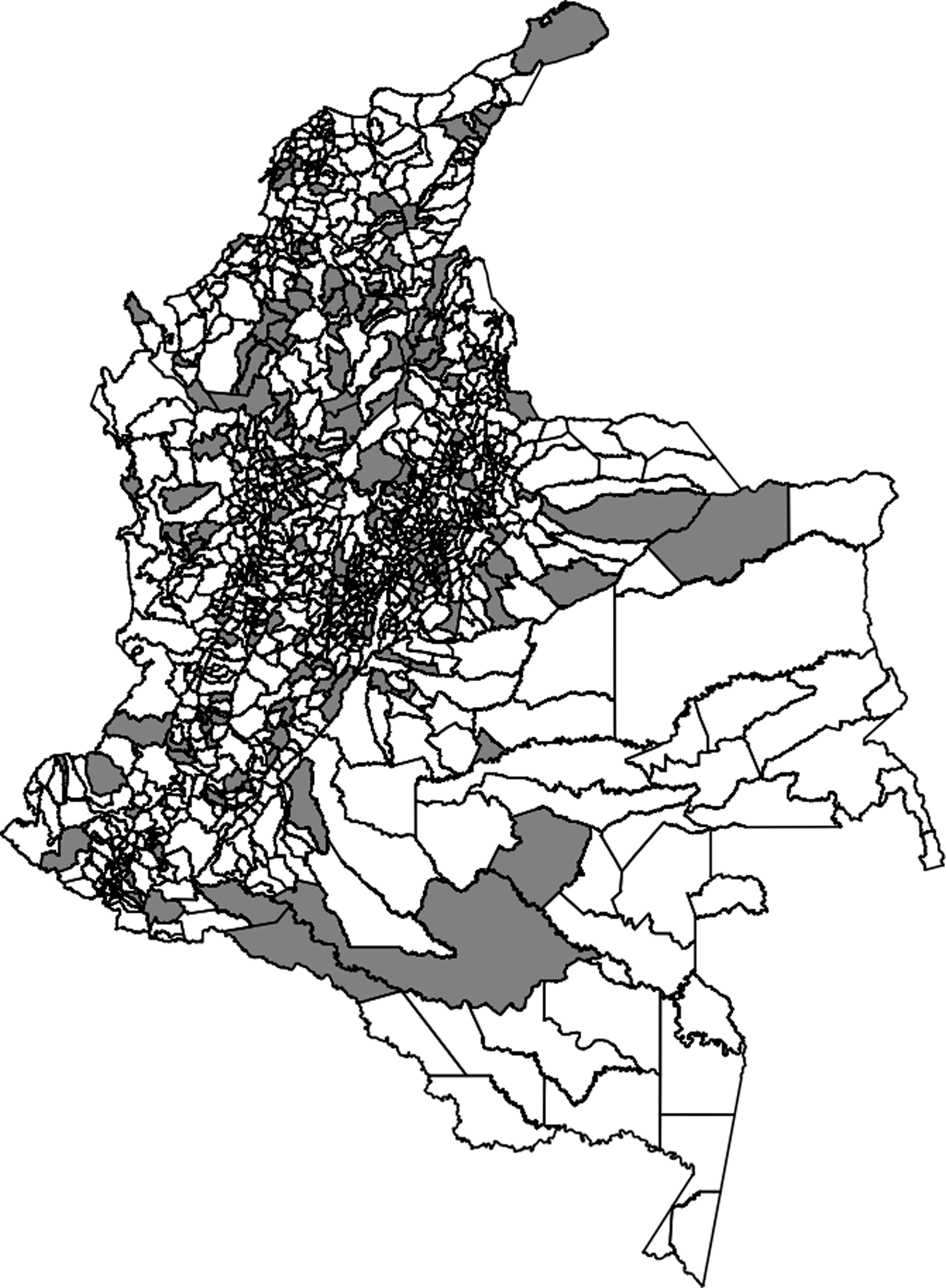

We applied a survey instrument to mayors participating in the National Congress of Municipalities organised by the Colombian Federation of Municipalities (FCM, in Spanish) in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, in March 2019. These mayors’ terms extended from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2019. The research team was permitted by the organiser, FCM, to attend all events at the convention. A total of 468 of 1,100 Colombian mayors attended the Congress. It is important to highlight that the mayors from the 32 departamento capitals and Bogotá do not belong to this association. Therefore, they were not expected to attend this Congress. We surveyed a convenience sample of 250 mayors from 27 of the 32 Colombian departamentos. Conference attendance likely involved self-selection, as mayors from nearby locations and from larger and wealthier municipalities could be expected to encounter fewer barriers to attendance. However, Figure 1 shows that surveyed mayors are well distributed across the country. Only the scarcely populated areas corresponding to the Amazon rainforest and the Orinoco basin lack representation in the sample.

Figure 1. Municipalities included in the survey experiment (in grey).

Once at the event venue in Cartagena, the research team members, who are native Spanish speakers, randomly approached mayors after meals, during summit breaks, in the hotel lobby and the exhibition hall over three days. After agreeing to participate, mayors received a hypothetical scenario and a post-treatment survey of 20 questions about their personal background, estimated number of Venezuelans immigrants in the municipalities, and their municipalities’ most important problem, among other information.

As the experiment involves four possible municipal conditions or scenarios, each mayor was assigned to one of these four scenarios by chance. To guarantee random assignment of the municipal condition, we printed and organised the municipal scenarios in sets of the four stacks. Then, we consecutively alternated the municipal scenario from each stack whenever we approached a mayor. This way, every time we assigned one out of the four scenarios, we were proportionally increasing the number of mayors per each experimental condition while maintaining randomisation of the treatment.

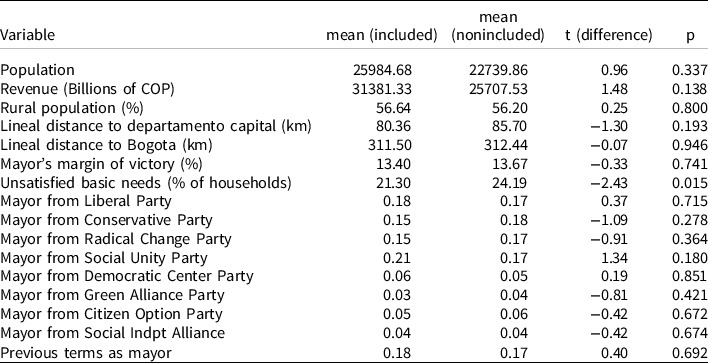

Although the sample was not selected randomly, these municipalities fairly represent the overall population of Colombian local governments, excluding the capital cities. Table 1 presents a comparison between included and nonincluded municipalities in terms of socioeconomic, geographic, and political variables. Differences between groups are statistically insignificant except for the percentage of households with unsatisfied basic needs according to the 2018 national census. However, this difference is not substantial, as included municipalities have just 2.8 percentage points fewer poor households than their nonincluded counterparts. Ideally, one should also compare individual characteristics between included and nonincluded mayors. However, these data are not publicly available.

Table 1. Characteristics of included and nonincluded Colombian municipalities

The study is a between-group 2 × 2 factorial design that results in four possible municipal conditions or scenarios: (1) visible issue and salient beneficiaries; (2) visible issue and nonsalient beneficiaries; (3) less visible issue and salient beneficiaries; and (4) less visible issue and nonsalient beneficiaries. Each mayor was randomly assigned to one of the scenarios. The instrument presented mayors with a context in which Venezuelan migrants made up 10% of their municipalities’ populations, and the national government allocated resources to provide social services to those migrants. Ten percent is not a migrant share that is far removed from local realities – the average being 5% migrant population – and it facilitates the mental calculation needed to consider the hypothetical scenario. Moreover, migration from Venezuela not only is a highly relevant and ongoing crisis but it also allows the introduction of exogenous shifts to the local policy context. Indeed, migration recently has been used to represent external shocks for local governments in both observational (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Boyne, O’Toole, Meier and Walker2013) and experimental studies (Avellaneda and Olvera Reference Avellaneda and Olvera2018).

The experiment introduces two manipulation types. First, we manipulated issue visibility by presenting two different projects: (1) construction of classrooms and (2) vaccination and preventive health. While both projects are in the realm of social services and arguably belong to similarly salient policy areas, the school project involves infrastructure building, which makes it more visible in the long term than the health project. The second manipulation allows us to explore differences in the salience of beneficiaries for the municipal constituents.Footnote 2 To do so, we presented one set of scenarios in which migrants have Colombian relatives in the municipality and another set in which migrants are not related to the local population. We expect mayors to be more likely to take the project when migrants have Colombian relatives in their municipality, as mayors might politically capitalise and claim credit for benefiting their constituents’ relatives.

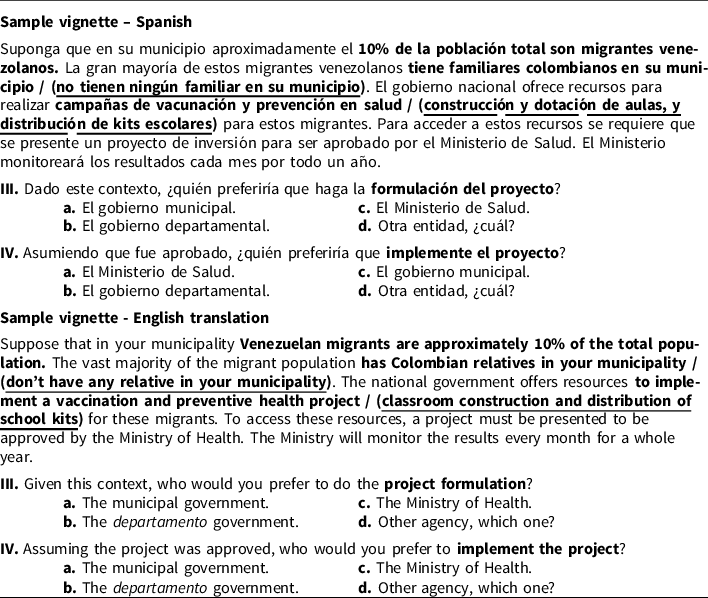

We asked mayors two questions: (1) Who would they prefer to formulate the project? and (2) Who would they prefer to implement the project? In both cases, we presented mayors with four options: the national government (either the Ministry of Education or Ministry of Health), the intermediate government (departamento), the municipality – of which they are the executive leaders – or another actor to be the formulator or implementer of the project, respectively. Table 2 shows an example of the vignette presented to the mayors in the original Spanish and its translation to English.

Table 2. Vignettes presented to Colombian mayors

Results

Descriptive results

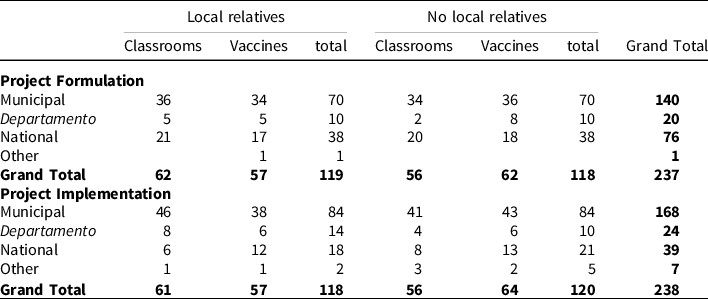

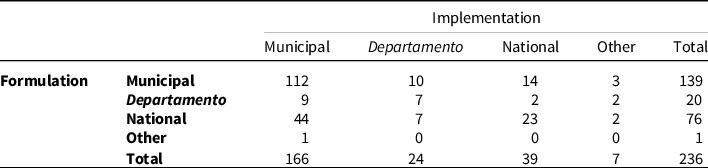

Table 3 presents the raw results of the survey experiment. The sample is roughly evenly split between treatment conditions regarding both project type and migrants’ local relatives. We obtained 237 full responses for the project formulation question and 238 for the project implementation question. Some clear trends appear from the data. First, most mayors chose to take the project’s formulation (59.1%) and implementation (70.2%). Second, the proportion of mayors taking project formulation is significantly smaller than the proportion taking project implementation (z = 2.53) at the 0.05 level. Although this is not an experimental result, it is consistent with our expectation that mayors will be more inclined to take on implementation than formulation. However, the relationship between formulation and implementation choices is not straightforward; not all the mayors who preferred autonomous formulation chose autonomous implementation. Table 4 presents the combination of choices involving formulation and implementation; 236 mayors answered both the formulation and implementation questions. To highlight the main trends: 114 mayors chose to take on both policy phases (municipal formulation and implementation), 24 mayors chose fully relinquishing to the central government (both national formulation and implementation), and 45 mayors chose national formulation and municipal implementation. Mayors seldom chose delegating formulation or implementation to departamentos.

Table 3. Summary results by manipulated scenarios

Table 4. Combinations of formulation and implementation choices

Balance testing of treatment groups

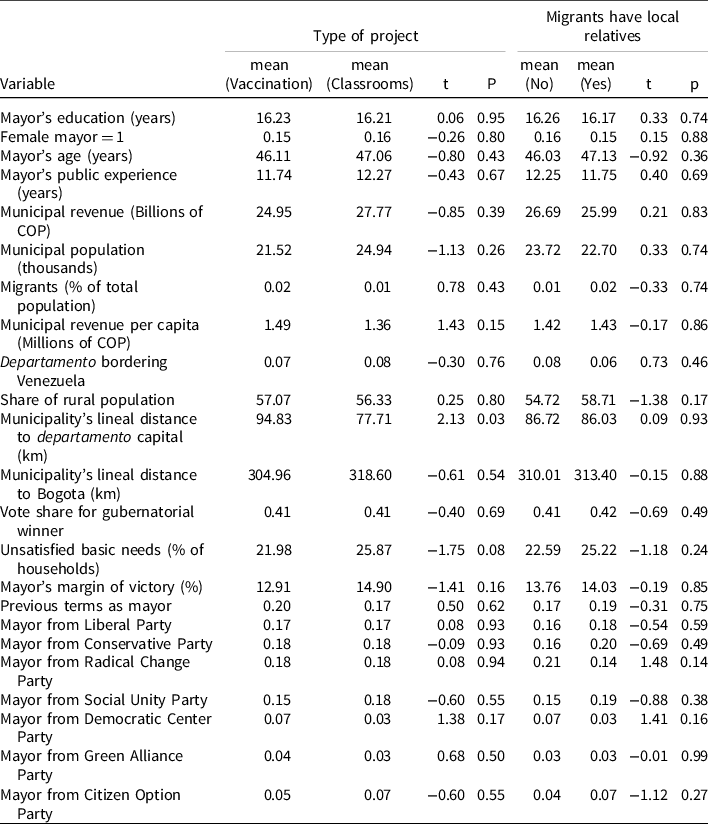

To check for equal subject characteristics across treatment groups, we surveyed the mayors’ demographic information, such as educational attainment, gender, and age, as well as socio-economic, geographic, and political indicators of their respective municipalities. Table 5 reports the balance of these covariates when dividing the sample by each manipulation – project type and migrants’ local relatives. None of the covariates presents a statistically significant difference between groups when treated for whether migrants have local relatives. Meanwhile, only the distance to the departamento capital presents a significant difference between groups by project type.

Table 5. Balance tests

Experimental analysis

Considering that the vignette offered mayors four choices for each question, we conduct a multinomial logistic regression to elicit the effect of the treatment manipulations. As an extension of the more common binary logistic regression, this model allows to predict the probability of occurrence of a group of (more than two) categorical outcomes. Once one of the outcomes is chosen as the baseline, the statistical analysis reports coefficients as changes in the odds of a particular outcome compared to the base category. In our case of study, selecting the municipal option as the baseline is convenient given that municipal action is the category most chosen in our sample, but also it reflects the mayoral choice to take on the project directly.

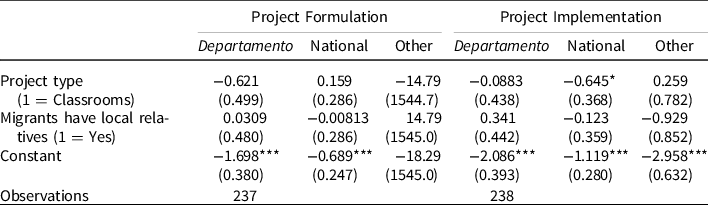

Table 6 presents the results of this estimation with municipal choice as the baseline for the formulation and implementation of the project. Thus, coefficients must be interpreted as changes in the odds of other outcomes occurring (preference for action by the Departamento, the national government or other actor) compared to the preference for municipal action. Neither project type nor migrants’ local relatives hold a significant effect on the project formulation choices. However, project type significantly affects national project implementation. Mayors are less likely to choose national project implementation than municipal implementation when facing a classroom construction project than a vaccination project. Particularly, the odds of choosing national project implementation decline by 50% in the case of classroom construction instead of a vaccination project. The findings hold when we include covariates in the multinomial logistic regressionFootnote 3 .

Table 6. Multinomial logistic regression – base choice: municipal

Standard errors in parentheses.

*p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

We grouped mayors’ choices to differentiate between mayors who preferred ceding the project to the national level and all other options. Even though we have a binary-dependent variable, we use OLS instead of logit or probit regression because it serves our goal of eliciting the causal effect due to the treatments. In other words, we want to identify whether there is a statistically significant difference in the discrete probabilities between groups (Angrist and Pischke Reference Angrist and Pischke2008). Should we have the case of a continuous probability distribution, logit or probit regression could have been more appropriate. Moreover, OLS coefficients directly allow to assess effect size.

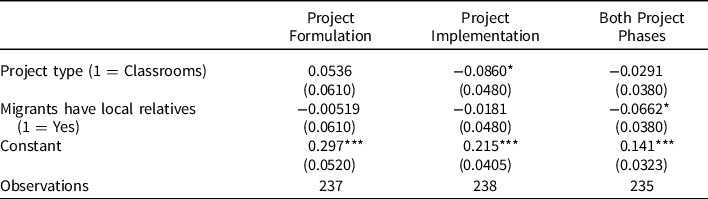

Table 7 presents OLS regressions for mayoral choice to cede the project to the national level. In the three models, the dependent variable is coded as “1” if there is national-level cession, respectively, for project formulation, implementation, or both project phases. Results evidence the same effect for project type on implementation observed with the multinomial logit framework. There is less likelihood, a difference of approximately 8.6 percentage points, of ceding authority for a classroom construction project than for a vaccination project. Moreover, mayors are significantly less likely to cede to the national level, by 6.6 percentage points, when Venezuelan migrants have local relatives. We asked mayors what they consider to be the main problem facing their municipalities. Only eight mayors mentioned education or health. Therefore, as a robustness check, we ran the statistical analyses removing these eight observations. Significant results hold.

Table 7. OLS regression for cession to national level

Standard errors in parentheses, *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Implications

Contextual levers of credit claiming

Our survey experiment with Colombian mayors, who are political and administrative executives of local governments, provides renewed evidence on the effect of contextual decision characteristics on executive decisionmaking for policy uptake and delegation. The literature often supports the dominance of blame avoidance over credit claiming (Weaver Reference Weaver1986), even more so when a crisis arises (Bach and Wegrich Reference Bach and Wegrich2019). However, this study suggests that credit claiming rationales play a significant role in shaping mayors’ decisions to delegate amid a sustained crisis. Moreover, results also suggest mayoral credit claiming opportunities may vary from one stage (formulation) to another (implementation) in the policy-making process.

The study shows mayors are less likely to cede decision-making power for implementing more visible projects, such as constructing classrooms. While both projects are associated with social services, the constructed classrooms constitute a more visible and tangible asset than the vaccination project. So, mayors might potentially use these achievements for political gain in the future. An alternative mechanism that also might increase the preference for autonomy regarding the classroom project is the potential for “bribe-generating” activities (Liu and Mikesell Reference Liu and Mikesell2014). The shift from a classroom construction project to a vaccination project is associated with a 9% drop in mayoral preference for local implementation. However, we do not see any effect of this treatment manipulation regarding project formulation.

Meanwhile, the second treatment manipulation included in this experiment – whether migrants had relatives in the Colombian municipality – does not seem to affect the choice of project formulation or implementation when studied independently. However, a substantial effect exists for the likelihood of ceding both project formulation and implementation to the central government. While 15.7% of mayors would prefer full cession to the central government when the project involves migrants without local connections, only 8% make the same decision when migrants have local relatives. Clearly, the salience of a project’s beneficiaries does not affect most chief executives when deciding on project uptake. However, the shift from more to less salient beneficiaries seems to have a strong effect among the small proportion of mayors who would rather cut ties entirely with a project if it does not directly relate to their constituents. We interpret these findings, in support of hypotheses 1 and 2, as evidence that mayors take into consideration the opportunities to claim credit for project implementation in their decision-making process. Such opportunities are reduced in a scenario in which projects are less visible, or the beneficiaries are not proximate to voters.

Other behavioural factors, not captured in this experiment, may also affect mayoral perceptions of the migrant population and salience attributed to it. Some qualitative data obtained during the survey data collection are evidence of substantially different approaches to migrants’ care as a policy problem. Some mayors have taken an arms-length approach to dealing with the migrant crisis. For instance, a mayor commented that the number of migrants in his municipality remains very low because he opted for busing them to the next big town. Other mayors have developed closer relationships with the migrants and may challenge the ideas of identity and salience in favor of a more humanitarian approach that leads to a positive social construction of the migrant population. For example, a mayor self-corrected when estimating the number of migrants in her municipality because she remembered that one of the migrant families had just had a baby. This seems to denote a higher degree of caring and attention to this population.

Implementation versus formulation

The lack of influence of shifting contexts on the delegation preferences for project formulation suggests this policy stage, unlike implementation, does not offer enough flexibility of incentives for credit claiming to influence mayors to change their decisions. Therefore, not only do contextual factors affect uptake preferences but these effects are contingent on policy stage, which also independently affects preferences. Moreover, while not tested in the experimental framework, this study shows the share of mayors that chose taking on project implementation is significantly greater than the share of mayors choosing project formulation’s uptake. These findings provide evidence in support of hypothesis 3.

This hypothesis and its corresponding findings run contrary to most studies of delegation, for instance at the federal level in the United States, where political actors are more likely to delegate implementation. In such scenarios, delegators may impose ex-ante restrictions or retain opportunities for ex-post control. Instead, our results contribute to the understanding of policy uptake in a context where decisionmakers hold no control powers over other policy actors. These results might indicate that mayors, deprived of control mechanisms once they cede autonomy, perceive greater incentives for credit claiming in the implementation versus formulation stage. Moreover, Colombian local governments’ lack of bureaucratic robustness particularly manifests in poor technical capacity for project formulation (Gaviria Reference Gaviria and García Villegas2018). Hence, the results correspond to a situation in which some mayors are more wary of assuming responsibility for formulating projects due to the risk of failing the approval process. Mayors would rather cede this responsibility to the central government and focus on implementation. In this stage, they have more chances to claim credit during the implementation itself (for instance, performing field inspections or visiting participating communities), as well as once they achieve a successful output.

Limitations and further research

The study faces some limitations. For instance, while findings can arguably be extended to most municipalities in Colombia, capital cities are particularly different from small municipalities, whose mayors are the subjects of this study. In Colombia, capital cities are the respective departamento’s largest municipalities in every case. Therefore, capital cities and their mayors face a different political and economic environment than the rest of the municipalities. Indeed, such differentiation was among the reasons for creating the Colombian Association of Capital Cities (Asocapitales) and withdrawing from the Colombian Federation of Municipalities (RCN Radio 2018; Asocapitales 2020).

Also, regarding external validity, one should carefully consider the characteristics of the institutional framework before generalising these findings to other countries’ local chief executives. For instance, while most Latin American countries have experienced a decentralisation process in the past few decades, each country’s process has advanced at different paces. That is evident with the considerable variation in autonomy vested to localities across the region. Therefore, mayoral perspectives on autonomy, delegation, and cession of decision-making power might differ, depending on the baseline level of power, resources, and responsibilities allocated to their respective local governments. While this limits the generalisability of this study’s findings, it also highlights the opportunity to replicate the study in other country settings.

Meanwhile, the small sample size may have contributed to the fact that several of the expected relationships are statistically insignificant while significant effects are relatively small. Certainly, our research design prioritised the opportunity to acquire in-person experimental evidence on decision-making levers from hard-to-reach political elites in a critical policy situation, while sacrificing the size of the sample. However, there might also be theoretical and contextual factors explaining these nonfindings. First, the null effects correspond mostly to the formulation stage which, as discussed previously, offers a narrower space for credit claiming given that mayors lack ex-post mechanisms for controlling implementation. Second, our case might lead to a conservative estimation of the levers’ effects, given that the institutional context surrounding Colombian mayors limits their immediate pursuit of political goals beyond their mayoral term. For instance, replicating the study in a country allowing for mayoral reelection may evidence a larger influence of credit claiming.

We also caution readers about the potential role of project duration on uptake and credit claiming. While a vaccination program may be implemented in a short period, the construction of a classroom may take months, and mayors may consider this time difference for credit claiming purposes. Indeed, the studied mayors were in the last year of their administration. Therefore, future studies should address the effect of electoral cycle on credit claiming and project uptake.

Finally, while some theoretical frameworks (Soss and Schram Reference Soss and Schram2007) discuss the influence of visibility and proximity on policy feedback, this study operates on the basis that mayors can assess such eventual feedback. This might not necessarily be the case. Mayors might be underestimating the differences in visibility between the proposed projects. Also, they might be relying heavily on their own social construction of migrants and thus misperceiving the proximity or salience of migrants to their constituents. Further studies might address this limitation by gauging the mayors’ perceived visibility and beneficiary salience.

Policy implications

Overall, only a small share of mayors preferred involving the intermediate level of government, the departamento, at any stage. This finding is somewhat surprising, given the substantive role departamentos play in providing education and health care in Colombia. A plausible interpretation might be mayors willing to cede decision-making power might look for a more capable level of government. Given the strong tradition of centralisation in Colombia, only modified in recent decades, mayors might still perceive the central government as more capable than intermediate governments, which are not yet ready to consolidate their roles in the governance system (Estupiñán Achury Reference Estupiñán Achury2012). Furthermore, mayors might prefer the more distant authority, such as the national government, when declining project uptake if their motivation is to shift the blame in case projects fail (Mortensen Reference Mortensen2012).

Despite the institutional context’s caveats, this research offers some policy implications for national governments in their interactions with local governments, particularly amid social crises. In a general sense, this study reinforces the idea that central governments ought to take into consideration local officials’ incentives and motivations (Weingast Reference Weingast2014). More particularly, mayors’ strategic behaviour to favor their political prospects might play a role in their decisions to take on policy projects or relinquish them to other levels of government. Such behaviour might bring results not aligned with the national government goals, thus risking potential imbalances or inequalities. Therefore, national governments might need to directly provide services in policy areas where impact is less visible, as these are less preferred by some mayors. Similarly, as certain mayors reflect preferences for groups more salient to their constituents, national governments might need to intervene to guarantee the provision of services to less salient populations. This is particularly important for crisis-related issues, such as the attention to migrants and refugees, which localities soon can perceive as a burden if national governments opt against taking the main role in coordinating policy formulation and implementation.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BZYKYV.

Acknowledgements

This research would have not been possible without the cooperation of the mayors participating in the 2019 Colombian Congress of Municipalities and the staff members of the Colombian Federation of Municipalities (FCM). For their valuable research assistance, the authors would also like to thank Pedro Luis Blanco, Julieth Altamar, Laura Marcela Villa, and Ricardo Bello Pascuas. Previous versions of this manuscript were presented at the annual meetings of the American Political Science Association (APSA) in Washington DC in August 2019 and the Southern Political Science Association (SPSA) in San Juan in January 2020. The authors owe special thanks to participants at these conferences, as well as Sean Nicholson-Crotty, Lee Alston, James Perry, and Amanda Rutherford for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of interests

The author(s) declare none.