Introduction

At reproductive age, women in low- and middle-income countries are vulnerable to malnutrition(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1). However, maternal under-nutrition is a severe public health problem globally accounting for 45 % of all maternal deaths(Reference Rush2). Moreover, physiologically the nutritional demand increases during lactation. During this phase, the requirements for both energy and essential nutrients are higher(Reference Meyers, Hellwig and Otten3).

Dietary practice is a major challenge in developing countries that take the line-share for the cause of under-nutrition(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1,4) . A lack of access to an adequate diversified diet is identified as one of the severe problems among poor populations(Reference Khan and Khan5). Dietary diversity (DD) is considered as the proxy indicator for measuring dietary adequacy among individuals(Reference Ruel6). Maternal under-nutrition is the major challenge, and it is the global agenda as central to health and sustainable development(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1).

Ethiopia is one of the low-income countries with the highest levels of malnutrition among lactating women in sub-Saharan Africa(Reference Hazarika, Saikia and Hazarika7,Reference Hundera, Gemede and Wirtu8) . Similarly, the limited studies conducted from Ethiopia such as Aksum(Reference Weldehaweria, Misgina and Weldu9) and South Gondar(Reference Girma and Degnet10) showed that DD of lactating mothers was low. Additionally, there is no documentation on the predictors of DD among lactating mothers in the Afar pastoralist community, Ethiopia. The present study aimed to determine the magnitude of meeting minimum dietary diversity score (MDDS) and its predictors among lactating mothers in Abala district, Afar pastoralist community, Ethiopia. This will help in designing a proper intervention to improve maternal nutrition and easily access information for further research about lactating mothers.

Methods

Study design, setting and period

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Abala district, Afar region, Ethiopia. The district is located about 942 km northeast of Addis Ababa and 491 km far from the regional capital city, Samara. According to the projection of the 2007 national Census, the district has a total population of 43 372 with an area of 1188⋅72 km2. From the Abala health bureau report, the district has one general hospital, four health centres and eight functional health posts. The study was conducted from 5 January 2020 to 10 February 2020.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The source population was all lactating women in the Abala district who had a child aged less than 24 months. Mothers were excluded if they were seriously ill and have physical deformities which alter the procedures to take correct anthropometric measurements.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using the open EPI-info version 7.1.1 with considering the assumptions of 17⋅2 % magnitude of MDDS from a study done in Ghana(Reference Zakaria and Laribick11), 5 % margin of error, 95 % confidence interval (CI), 10 % non-response allowance and 1⋅5 design effect. The calculated final sample size was 362 lactating women.

Sampling procedure

The study participants were selected using a multi-stage sampling technique. The Abala district has a total of 14 kebeles, from which 5 kebeles were selected randomly. The sample size was proportionally allocated based on the total number of lactating women in each selected kebele (from the health extension worker's family folder). Finally, study participants were selected using a systematic sampling method. In households where there are more than one lactating women, a lottery method was used to select one participant.

Data collection procedure and quality control measures

A semi-structured questionnaire was developed through a critical review of relevant literature. The questionnaire was consisting of socio-demographic characteristics, maternal healthcare practice, maternal dietary feeding practice, sanitation and hygiene-related factors, and anthropometric measurements. Six diploma-holder health professionals as data collectors and two master-holder public health professionals as supervisors were recruited. Data were collected by direct face-to-face interviewing with lactating mothers and measuring anthropometry.

The dietary diversity of lactating women was collected using the women's dietary diversity score (WDDS). It is calculated by a simple count and summing-up of the number of food groups that an individual respondent has consumed over the preceding 24-h recall period regardless of the portion size from the nine food groups. The calculated MDDS is taken as the consumption of at least four or more food groups. A minimum meal frequency is also calculated by counting the frequency of meals an individual took 24 h before the survey(Reference Kennedy, Ballard and Dop12). The maternal mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) was measured using UNICEF measuring tape to the nearest 0⋅1 cm.

Data quality control measures

The research questionnaire was prepared in the English version and translated into the local language (Afar af). Pre-testing was done on 10 % of the sample size in the none-selected kebeles of the Abala district. Data collectors and supervisors were selected based on their fluency in the local language and they were trained on data collection techniques.

The anthropometric measurement (MUAC of the lactating mother) was performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) standardised procedures. It was measured by placing WHO MUAC measuring tape on the upper-middle arm between the acromion and olecranon process of the non-dominant hand. Duplicate anthropometric measurements were done in case of deviations from standard procedures in measuring to minimise measurement errors. Continuous supervision and follow-up of the data collectors were made to review and check for completeness and consistency of the collected data on daily basis. The collected data were handled and stored carefully and appropriately.

Data processing and analysis

The data were cleaned and entered into the latest Epi-data version 4.6.02, and transferred to statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 25 software for statistical analysis. The study results were presented as mean (sd) or numbers (%).

The statistical association was determined using bivariable and multivariable logistic regressions were used. Statistical significance was determined using the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratio with 95 % CI and P-value <0⋅05. Predictor variables that have an association with the outcome variable at bivariable analysis with a P-value of <0⋅25 were selected and included in the multivariable logistic regression model. Analysis was done using a backward logistic regression model and, variables with a P-value < 0⋅05 in multivariable analysis were declared as statistically and independently significant predictors of under-nutrition among lactating mothers.

The final model was tested using Hosmer and Lemeshow's χ 2 test P-value, and it was P = 0⋅821, which showed that the model was the best fit. The percentage of the model that was accurately classified was 82 % and the extent of multi-colinearity was also assessed using standard error cut off two, and no variables were found.

Ethical considerations

The present study was extracted and analysed from a study conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the ethical review committee of Samara University College of Health and Medical Sciences (Ref: ERC0053/2019). Informed verbal consent was obtained from all subjects (verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded).

Operational definitions

• Minimum maternal dietary diversity score of lactating women

◦ Met: If the mother ate at least four and above food groups from the nine food groups 24 h preceding the survey.

◦ Not met: If the mother ate less than four food groups from the nine food groups 24 h preceding the survey.

• Minimum meal frequency:

◦ Met: If the mother consumes at least four times and above times per 24 h preceding the survey, regardless of portion size.

◦ Not met: If the mother consumes less than four times per 24 h preceding the survey, regardless of portion size.

■ Maternal under-nutrition

◦ Yes: if MUAC < 23 cm and

◦ No: if MUAC ≥ 23 cm

■ Lactating mother: A mother who was breastfeeding her child at the time of the survey.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A total of 360 lactating mothers were included in the present study with a 99⋅4 % response rate. The mean (±sd) age was 29⋅68 (±7) years. The majority 297 (82⋅5 %) and 311 (85 %) of them were rural residents and Afar in ethnicity, respectively. More than half, 222 (61⋅7 %) of mothers did not receive a formal education (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristics among lactating mothers in Abala district, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360)

MDDS, minimum dietary diversity score.

*Tigray and Amhara; **Single, divorced and widowed; ***Governmental and NGOs; ****Daily labour.

Lactating mothers health care and nutrition-related characteristics

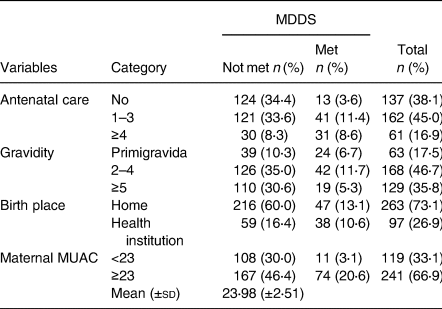

More than one-third, 137 (38⋅1 %) of mothers were not attending antenatal care (ANC) follow-up. Of all study participants, institutional delivery for the index child was 97(26⋅9 %). The mean (±sd) score of maternal mid-upper arm circumference was 23⋅98 (±2⋅51) cm (Table 2).

Table 2. Health care-related characteristics among lactating mothers in Abala district, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360)

MDDS, minimum dietary diversity score.

Lactating mothers feeding practice

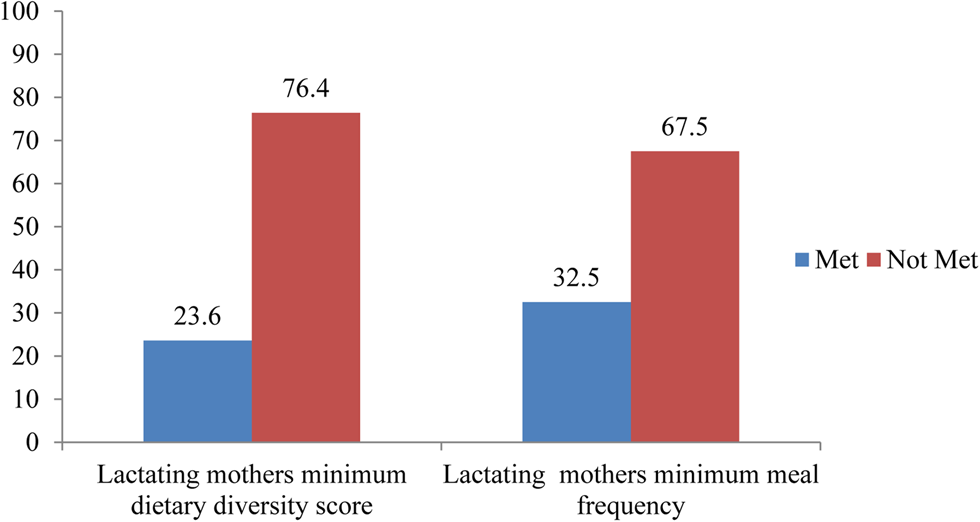

Less than two-third, 228(62⋅3 %) of study participants were getting nutrition-related counselling. There was food taboo during lactation in 7(1⋅9 %) of them. Two hundred and seventy-five (76⋅4 %) of study participants had a low dietary diversity score, while 84 (22⋅9 %) and 4 (1⋅1 %) of them had medium and high dietary diversity scores, respectively. The mean (±sd) score of maternal DDS and maternal meal frequency was (3⋅09 ± 0⋅875) and (3⋅33 ± 0⋅570), respectively. Only, 88 (24 %) of lactating mothers met the MDDS, while 117 (32⋅5 %) of them met the minimum meal frequency. In the last 24 h preceding the survey, all study participants consumed starchy staples, but only 16⋅4, 3⋅8 and 2⋅7 % of them had consumed dark green leafy vegetables, eggs and organ meat, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Percentage of women's minimum dietary diversity score (WMDDS) and minimum meal frequency for women (WMMF) among lactating mothers 24 h before the survey in Abala district, pastoralist community, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360).

Fig. 2. Percentage of food group consumption among lactating mothers 24 h before the survey in Abala district, pastoralist community, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360).

Lactating mothers feeding practice one week before the survey

One week before the survey, all study participants consumed starchy staple foods and legumes. The least food groups consumed by study participants a week before were organ meat and other meat groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Proportion of lactating mothers who consume different food groups (at least one times) a week before the survey, in Abala district, pastoralist community of Afar region, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360)

MDDS, minimum dietary diversity score.

Sanitation and hygiene-related characteristics of study participants

The majority 331 (91⋅9 %) of the study participants got water from protected sources, and more than half 203 (55⋅5 %) of them had no latrine. Nearly three-fourth, 271 (74⋅0 %) of study subjects dispose of solid waste at open fields (Table 4).

Table 4. Sanitation and hygiene-related characteristics of study participants in Abala district, the pastoralist community of Afar region, Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360)

MDDS, minimum dietary diversity score; VIPL, ventilated improved pit latrine.

Factors associated with MDDS

In the bivirate analysis variable like maternal residence, maternal age maternal educational status, maternal occupation, paternal occupation, family size, ANC follow-up, TV/radio ownership, maternal meal frequency, livestock ownership, gravidity, paternal education and birth place had significant association at P-value<0⋅25 with dietary diversity of lactating mothers (Supplementary Table S1 of Supplementary material),and entered into the multivariable logistic regression model to control the effect of confounders. Finally, paternal education, ANC follow-up and maternal meal frequency were maintained their consistency (Table 5).

Table 5. Factors associated with maternal dietary diversity score at multivariable logistic regression among lactating mothers in Abala district, Afar region, Northeast Ethiopia, 2020 (n 360)

MDDS, minimum dietary diversity score; AOR, adjusted odds ratio.

*P < 0⋅001, **P < 0⋅005, ***P < 0⋅05.

Discussion

The present study was done to determine the level of dietary diversity and its predictors among lactating mothers in Abala district, Afar pastoralist community National Regional State, Ethiopia. In the present study, the overall minimum dietary diversity among lactating mothers was 23⋅6 % (95 % CI 19 %, 28 %). The present study finding is similar to the study revealed in Oromia 23 %(Reference Bedada Damtie, Benti Tefera and Tegegne Haile13).

The MDDS in the present study is lower than as compared with studies done in other parts of Ethiopia such as Angecha district 47⋅8 %(Reference Boke and Geremew14), Dedo and Seqa-Chekorsa district 32⋅8 %(Reference Alemayehu, Argaw and Mariam15), Ataye district 48⋅8 %(Reference Getacher, Egata and Alemayehu16), Lay Gayt district 34⋅3 %(Reference Fentahun and Alemu17), Dessie town 45⋅5 %(Reference Seid18), Aksum town 43⋅6 %(Reference Weldehaweria, Misgina and Weldu9) and Debretabor 75 %(Reference Engidaw, Gebremariam and Tiruneh19) showed that lactating mothers met the minimum diet diversity. This finding is also lower than findings from other low- to middle-income countries such as Nepal 53 %(Reference Singh, Ghimire and Upadhayay20) and Malawi 28⋅1 %(Reference Kang, Hurley and Ruel-Bergeron21). In a case-control study in Dhaka, Bangladesh 42 %(Reference Hasan, Islam and Mubarak22) also has higher findings than the present study. But this finding is higher than from studies done in Leseto14⋅4 %(Reference Bonis-Profumo, Stacey and Brimblecombe23) and Ghana 17⋅2 %(Reference Zakaria and Laribick11). This difference might be due to sampling size, study design, setting, climate, tradition, poverty status and nutrition intervention.

According to the findings of the present study, the majority of lactating mothers consumed cereals in the preceding 24 h of data collection. It also showed that large proportions of the lactating mothers did not get source foods (egg, milk and milk products, organ meat, meat and fish). Additionally, a little proportion of lactating mothers consumed dark green leafy vegetables and other vitamin A-rich foods. This kind of feeding practice will expose mothers to different forms of malnutrition as evidenced from different studies(Reference Boke and Geremew14,Reference Kang, Hurley and Ruel-Bergeron21,Reference Hasan, Islam and Mubarak22,Reference Henjum, Torheim and Thorne-Lyman24) .

According to the present study, ANC follow-up, meal frequency and paternal education were the predictors for women's minimum dietary diversity score (WMDDS). The odds of meeting the minimum dietary diversity among women who attended ANC for one to three times and four and above times were 2⋅6 and 4⋅8 than those did not attend ANC follow-up services, respectively. The present study is consistent with the findings revealed from Nepal(Reference Singh, Ghimire and Upadhayay20). The possible explanation might be that participants who had attended ANC follow-up have nutritional counselling to utilise the diversified diet. It might be also due to higher education, more income and better diet on those who attended ANC follow-up(Reference Kang, Hurley and Ruel-Bergeron21,Reference Hundera, Gemede and Wirtu25) .

In the present study, mothers who met their minimum meal frequency were six times more likely to meet their MDDS than their counterparts. This is consistent with studies revealed in Ethiopia such as Lay Gayt district(Reference Fentahun and Alemu17) and Debretabor(Reference Engidaw, Gebremariam and Tiruneh19). The possible reason might be a mother will met the minimum meal frequency if they are from households with food security. As a result, households secured with food might have met the minimum dietary diversity(Reference Getacher, Egata and Alemayehu16).

Lactating mothers having paternal with the level of secondary educational status are more than two times more likely to met their dietary diversity than whose paternals’ do not have a secondary level of education. As the paternal educational status increases their nutritional knowledge might improve(Reference Ambikapathi, Passarelli and Madzorera26), which can influence maternal feeding knowledge, attitude and practice(Reference Getacher, Egata and Alemayehu16,Reference Agize, Jara and Dejenu27) . Even though in the present study maternal education failed at the multivariable logistic regression model to be an important predictor, it has contributed to meeting minimum maternal diet diversity studies revealed from Ethiopian districts(Reference Boke and Geremew14,Reference Getacher, Egata and Alemayehu16) .

Limitations of the study

The present study is a cross-sectional study that cannot assess the cause–effect relationship. The seasonal variation in food consumption might exist so that results regarding dietary information are only limited to the specific season of the year in which the study was conducted. Beyond this, the study did not address the market access and barriers.

Conclusion

The present study showed that more than three-fourths of the lactating mothers did not met their MDDS. Paternal education, ANC follow-up and maternal meal frequency were statistically independent predictors of dietary diversity. Therefore, interventions aimed at improving maternal dietary diversity should address those factors. Finally, the scientific community should study with a prospective cohort study design to address seasonal variability during the preharvest and postharvest seasons since dietary diversity is multifactorial to identify other independent predictors.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jns.2021.28.

Acknowledgements

We express our deepest gratitude to Samara University, College of Health Sciences for ethical clearance. Our great thanks also deserve to our study participants, data collectors, supervisors and language translators for their invaluable contribution to this study.

The data sets analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

G. F. M. conceived and designed the study, performed analysis, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. F. W. F. and K. U. M. involved in the analysis, interpretation of the data and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This manuscript does not report personal data such as individual details, images or videos; therefore, consent for publication is not necessary.

Samara University was the funder for this research. The funder has no role in the drafting of the proposal and preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.