Failure to attend out-patient appointments is a well recognised problem for psychiatric services, especially child mental health services. This can result in considerable wastage of staff time and compounds the problem of long waiting lists. Multiple factors are involved in non-attendance for first appointments, including a lower level of maternal education, older age of the referred child, parental belief that intervention may worsen the problem and unrealistic expectations for a rapid treatment response (Reference Ewalt, Cohen and HarmatzEwalt et al, 1972). A long waiting time has also been found to increase the rate of non-attendance (Reference Subotski and BerelowitzSubotski & Berelowitz, 1990). Jones & Bhadrinath (Reference Jones and Bhadrinath1998) found that general practitioners' (GPs') main concern regarding prioritisation of child mental health problems was the time taken for non-urgent referrals to be seen. Several initiatives to decrease waiting time to first appointment and improve attendance at child mental health clinics have been described recently (Reference Munjal, Latimer and McCuneMunjal et al, 1994; Reference Wenning and KingWenning & King, 1995; Reference GeekieGeekie, 1995; Reference Potter and DarwishPotter & Darwish, 1996; Reference Roberts and PartridgeRoberts & Partridge, 1998). We report on our novel initiative to reduce our waiting time to first appointment.

Our service is a community-based child and adolescent mental health service for a population of children aged 0-16 years in west London. We receive around 850 referrals per year. A long waiting time from referral to first appointment had evolved as demand exceeded local resources. Up to 1997, referrals were dealt with by similar methods to those described by Roberts & Partridge (Reference Roberts and Partridge1998). Referrals were reviewed daily by team members and a prioritisation system for waiting list placement was used. This decision was made on clinical grounds using information provided by the referrer. This process used up a considerable proportion of staff time and resulted in a long waiting time and high rates of non-attendance at first appointment. Figures from 1995-1996 showed that average numbers on the waiting list were 200. While 25% of patients were seen within one month of referral, 30% waited longer than six months, with some waiting up to nine months. In early 1996, a preliminary project was successful in temporarily achieving a reduction in the waiting list. Staff enthusiasm was harnessed and a more focused, defined and team-based waiting list pilot project was developed.

The pilot project consisted of a ‘triage’ style assessment. Families were invited to a one-off appointment to more fully assess the presenting problem. The triage process had several aims.

-

(a) To lessen the waiting time from referral to first assessment. This was in response to increasing pressure from referrers and families to be seen sooner.

-

(b) To assess more fully and accurately the reason for referral. This would enable a better judgement to be made about the appropriateness, urgency and treatability of the referral, and facilitate clearer management planning.

-

(c) To improve attendance rates at first appointments. By reducing the waiting time to first appointment and judging motivation to attend, it was hoped less clinical time would be wasted and non-attendance rates would improve.

-

(d) To prevent a deterioration in symptoms which might occur with a prolonged waiting time.

The study

A sample of new referrals not requiring immediate allocation for assessment and treatment were allocated to a specific triage event-day. Waiting list cases were also directed into the triage system. A key feature was the structural organisation of the event. It began with a multi-disciplinary group meeting to generate hypotheses about the families attending. The day ended with a similar meeting outlining the assessments and action plans needed. This structure enhanced the sense of staff group participation.

Two triage days per month were set aside to see these families with each professional seeing one family per half-day. This structure allowed the clinicians' other work to take place as well. The referred child, the parents and other family members were invited to attend this initial appointment. A standardised letter explaining the purpose of the session was sent to each family, together with a Strengths and Difficulties questionnaire (Reference GoodmanGoodman, 1997) and a short departmental questionnaire routinely used which invites the parents to describe their view of the problem. The appointment was not conditional upon the return of these questionnaires. The parent was asked to confirm intention to attend. If no confirmation was received, the administration staff contacted the parent by telephone to ask if they still wished to attend.

After the multi-disciplinary group meeting, the clinician met with the family for an hour-long assessment session, using a semi-structured interview, to gain a relevant overview of the presenting problem. All cases were then discussed with the consultant child psychiatrist and other team members as outlined and decisions were made on further management. The options included immediate allocation, priority or routine position on the waiting list, closure or referral to another more appropriate agency. The details of the interview and resulting decision were recorded by the clinician. The GP and family were informed of the decision by letter. At the end of each triage day, the participating clinicians completed a log of the information gained and discussed the individual clinician's experience of the process.

The outcome of the triage initiative was compared with the activity in 1995-1996.

Findings

Over a six-month period, a total of 155 patients were allocated to the triage initiative. This ran alongside the original system for all other cases not allocated to the triage sample.

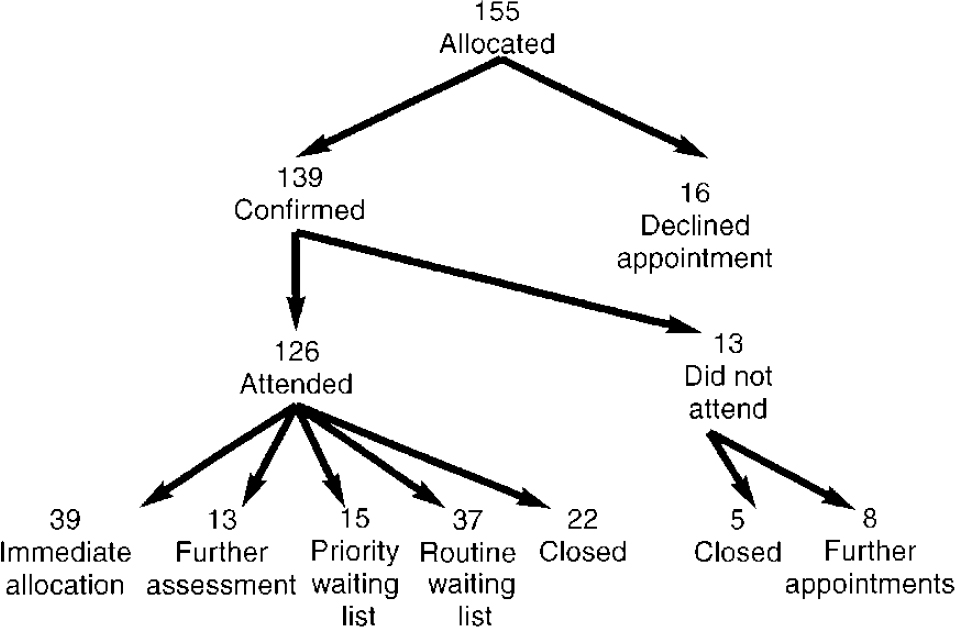

Of the 155 allocated 139 (89.7%) confirmed they would attend the appointment offered, 16 (10.3%) declined the appointment, of the 139 who confirmed, 126 (81.3%) attended, 13 (8.4%) did not.

The outcome decisions of the triage appointment were as follows (see Fig. 1): 13 (8.4%) were considered to require further assessment and were offered a second triage appointment; 39 (25.2%) were considered to require immediate allocation; 37 (23.9%) were placed back on the routine waiting list and 15 (9.7%) were given a prioritised place on the waiting list. Fourteen (9%) were considered not to require a further appointment and the case was closed while eight (5.2%) were referred on to a more appropriate service. Of those who did not attend, five (3.2%) were closed and eight (5.2%) were held for a further appointment. Thus, a total of 43 (27.7%) cases were closed.

Fig. 1. Triage decisions.

At the end of the six months, the waiting list to first assessment averaged 56. Of the original 155 cases, 82 were removed from the waiting list.

Discussion

Of those who confirmed, an unusually high percentage of patients attended the first appointment (81.3%). This may have been due to a decrease in waiting time, but it should be noted that a considerable proportion of these patients had already spent some time on the waiting list. The higher rate of attendance is likely to have been affected by the efforts of the administration staff in telephoning those families who did not respond to the initial request to confirm attendance.

Slightly higher numbers than the pre-triage process were assessed as requiring immediate allocation. In triage, reasons given by the clinicians for deciding on immediate allocation included the judgement that useful work had already emerged out of a session with some families and this should continue without further delay. Some cases had already waited their full time on the waiting list and were therefore immediately allocated. Some were deemed urgent or complex and in a small proportion of cases family pressure may have prompted a decision to immediately allocate.

The triage process had the following outcomes: 43 cases were closed and a total of 82 cases were removed from the waiting list.

The families expressed satisfaction with the process overall and clinicians' concern that those families placed back on the waiting list or closed would be dissatisfied was not realised.

The clinicians felt they were able to assess the appropriateness of the referral more accurately and therefore implement the correct course of management sooner. Team morale also improved as the structure of the process provided a sense of team activity and allowed the opportunity to share views on the cases and further management plans. This felt supportive and facilitated shared learning among staff.

The referrers also judged this initiative as worth-while with the resulting reduced waiting list volume and time. The triage initiative resulted in a much shorter waiting time to first assessment for new referrals to the service.

This triage initiative has been implemented as standard practice for all referrals to our service. All new referrals are now assessed within 13 weeks of referral being received. Further spin-offs have also been realised: in the six months following the trial period the waiting list to first assessment averaged 56 and now there is no longer a waiting list for treatment following this initial assessment. We would recommend this initiative as a successful model for others to use in decreasing waiting times and providing a more efficient and accurate screening process of referrals.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.