Judicial decisions defending the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons have regularly been criticized for going too far, too fast. It is no surprise that opponents of gay rights have denounced these decisions as examples of illegitimate judicial activism, but some supporters of gay rights have also criticized them as strategically unwise. In doing so, these supporters have echoed a long-standing scholarly argument that rights-based litigation strategies are ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst. In the gay rights context, one version of this argument has been particularly prominent: even when rights advocates win in court, those victories inevitably spark a political backlash, with the voters and their elected representatives reversing the judicial decisions and enacting regressive policies that are worse than the status quo ante.

A closer inspection of the actual sequence of victories and defeats for LGBT rights advocates in the United States, both in court and out, complicates this backlash narrative to a significant degree. Judicial decisions supporting LGBT rights have repeatedly fueled political countermobilization, but that has not been their only or even their most prominent effect. To the contrary, litigation has contributed in a variety of ways to expanding the rights of LGBT persons to act on their sexual identities without government interference, to be protected from invidious discrimination, and to form family relationships that are recognized by the state. If the backlash thesis is misleading even in this context—which its proponents have recently adopted as an illustrative case providing clear confirmation of their preexisting thesis—then it may be worth reexamination in other contexts as well.

The Backlash Thesis

One of the leading claims of the scholarly literature on the limits of judicial power is that unpopular judicial decisions provoke political reactions that undercut their effectiveness. This thesis has been developed most fully by Klarman, who has argued for more than a decade that the chief impact of the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) was to exacerbate the racist rhetoric and segregationist policies that characterized Southern politics at the time. On Klarman's account, Brown sparked massive resistance, polarizing Southern racial politics and undermining the efforts of white moderates. As a result, when Southern blacks turned to direct action protest in the early 1960s, they were met with increasing violence. Because it was Northern revulsion at Bull Connor's fire hoses and police dogs that led to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Klarman sometimes suggests that the Brown litigation ultimately produced progress on civil rights (Reference KlarmanKlarman 2004:385, 441–2; Reference Klarmansee also 1994). At other times, however, he emphasizes that racial liberalism was gradually but steadily advancing before the Court clumsily intervened, sparking a resurgence of white supremacy and thus undermining the very cause the justices were hoping to promote (2004:442, 464–5). Toward the end of his 2004 book on civil rights, Klarman identifies same-sex marriage (SSM) litigation as one of several recent examples that fit the counterproductive pattern set by Brown (2004:465). Elaborating the claim in a subsequent article, he insists that the Massachusetts high court's landmark 2003 decision legalizing SSM met a fate similar to that which followed every other effort by judges to defend a rights claim that lacked popular support: “The most significant short-term consequence of Goodridge [v. Department of Public Health 2003], as with Brown, may have been the political backlash that it inspired. By outpacing public opinion on issues of social reform, such rulings mobilize opponents, undercut moderates, and retard the cause they purport to advance” (Reference KlarmanKlarman 2005:482).

Like Klarman, Rosenberg is most well known for his revisionist and pessimistic account of Brown but has also advanced a similarly negative assessment of contemporary SSM litigation. Where Klarman has long emphasized the political backlash sparked by Brown, Rosenberg has generally characterized the decision as inconsequential rather than counterproductive, emphasizing that judges are usually unwilling and always unable to impose unpopular rights on the nation at large. In the original 1991 edition of The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change?, Rosenberg noted the backlash phenomenon only in passing, and he even responded to an early version of Klarman's argument by objecting that Klarman had overstated Brown's negative impact (1991:342, 1994; see also Reference GarrowGarrow 1994). In a revised 2008 edition of The Hollow Hope, however, Rosenberg has added 80 pages of new material on SSM litigation, extensively documenting the conservative countermobilization that followed the LGBT rights movement's state high court victories in Hawaii, Vermont, and Massachusetts.

According to this backlash narrative, SSM litigators won three big cases from 1993 to 2003, but each of these judicial decisions provoked political setbacks that made things worse. The Hawaii Supreme Court's 1993 decision in Baehr v. Lewin reached no final judgment on the state's discriminatory marriage laws but imposed a legal standard for justifying those laws that the state was unlikely to meet. Far from advancing the cause, however, this judicial victory produced a state constitutional amendment reversing the decision, a similar state constitutional amendment reversing a copycat judicial decision in Alaska, a federal statute declaring that the national government would not recognize SSMs and authorizing state governments to refuse such recognition as well, and statutory bans on SSM in more than 30 states by the end of 1999. At that point, the Vermont Supreme Court revived the movement's hopes by ordering the state to extend all the rights and benefits of marriage (though not the name) to same-sex couples, but this victory in Baker v. State of Vermont was followed by six more states banning SSM, including constitutional bans in Nebraska and Nevada. In Vermont itself, the state legislature responded to the court by enacting a Civil Unions Act in 2000, but the legislators paid for this decision at the polls, with an unusually large number of incumbents voted out of office later that year. Finally, 2003 witnessed the U.S. Supreme Court's invalidation of the last remaining criminal sodomy statutes in Lawrence v. Texas, followed several months later by the first decision from an American court to actually legalize SSM (Goodridge v. Department of Public Health 2003). In a pattern that should now be clear, these landmark victories led to significant electoral setbacks, including President George W. Bush's reelection the following year and the enactment of 23 new state constitutional bans on SSM by 2006. In sum, the litigation campaigns waged by LGBT rights advocates have regularly provoked both electoral and policy setbacks, reversing the gains won in court and producing executives, legislatures, and eventually judiciaries that are less supportive of LGBT rights than they were before.

Despite objections from a number of quarters, the general argument about the limited and unintended consequences of judicial decisions has been widely influential. This account is sometimes presented as a cautionary lesson for judges, urging them to temper principle with prudence (Reference PosnerPosner 1997; Reference RosenRosen 2003, Reference Rosen2006; Reference SunsteinSunstein 1996:96–8). In addition to this lesson about judicial humility, the backlash account is often framed as a warning to (or rebuke of ) movement activists, whose purportedly unreasonable demands for the courts to guarantee equal marriage rights are blamed for every subsequent political setback. The most recent iteration of this argument has revolved around whether SSM advocates are to blame for President Bush's 2004 reelection, but the wisdom of the SSM lawsuits has been a subject of considerable debate within the LGBT rights movement for a long time. When the Hawaii suit was filed in 1991, most leaders of the movement opposed the effort. The case was initiated by three same-sex couples and their private attorney, and both the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) declined invitations to sign on. Writing two years earlier, the executive director of Lambda Legal had noted that “[a]s far as [he could] tell, no gay organization of any size, local or national, [had] yet declared the right to marry as one of its goals” (Reference StoddardStoddard 1989:11–12). This choice was partly ideological—some gays and lesbians had no interest in joining the patriarchal institution of marriage—but it was partly strategic as well, with most advocates concluding that the goal was politically unattainable at the time.

The organized movement is now fully committed to the SSM campaign, but some of its most prominent scholarly supporters have continued to object on strategic grounds. Relying heavily on Rosenberg's account, Rimmerman has emphasized the limited capacity of judicial institutions to effectively construct and implement public policy and has suggested that the 1993 Baehr decision did “more for opponents of lesbian and gay marriage than for its proponents” (2002:78). Expressing the point even more sharply, D'Emilio has complained that “[t]he campaign for same-sex marriage has been an unmitigated disaster. Never in the history of organized queerdom have we seen defeats of this magnitude.” In fact, “[t]he battle to win marriage equality through the courts has done something that no other campaign or issue in our movement has done: it has created a vast body of new antigay law” (2006:10, emphasis in original; see also 2007:59). Echoing the conclusions of the Rosenberg/Klarman thesis, these internal movement critics have complained that litigation leads either to judicial defeats that achieve nothing or to judicial “victories” that provoke a counterproductive backlash. Either way, litigation campaigns draw resources from alternative strategies that are likely to be more effective.

A number of detailed scholarly accounts of LGBT rights litigation have advanced more optimistic (or at least more nuanced) assessments, but these works have drawn less attention than have the broad critiques of litigation. In a noteworthy comparative study, Reference SmithSmith (2008) has argued that the American LGBT rights movement has been less successful than its Canadian counterpart over the past 15 years, but that much of the success that both movements have had has been the product of litigation. Likewise, Andersen's definitive study of Lambda Legal emphasizes “both the promise and the limits of legal mobilization as a tactic for achieving social reform” and makes clear that “there are at least some circumstances in which reformers can be served by turning to the courts” (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:216). Citing Rosenberg, Andersen agrees that “courts do not have the capacity to produce social change when their decisions diverge too radically from the values and expectations of the other two branches of government,” but she insists nonetheless that “litigation [has] produced some favorable shifts in the legal and cultural frames surrounding gay rights” (2005:216–18). Eskridge likewise acknowledges the “antigay backlash” provoked by Baehr but also notes that “the litigation in Hawaii sowed the seeds for [the subsequent litigation in] Vermont” (Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:26, 45). Drawing on interviews with many of the key participants, Eskridge concludes that “Baehr opened up lesbian and gay imaginations to the possibility that their relationships might be recognized by the state as civil marriages, and it can hardly be surprising that many of the galvanized ended up as plaintiffs in court” (2002:45). Drawing on a similar set of interviews a few years later, Pinello argues that

Goodridge brought about enormous social change …. With nearly all other state and national policy makers at odds with its goal, the Massachusetts [high court] nonetheless achieved singular success in expanding the ambit of who receives the benefits of getting married in America, in inspiring political elites elsewhere in the country to follow suit, and in mobilizing grass-roots supporters to entrench their legal victory politically. (2006:192–3; see also Reference MezeyMezey 2007)

Courts and Causal Mechanisms

These competing assessments are rooted in competing conceptions of judicial power and historical change. If American courts are too weak to do anything helpful, then LGBT rights advocates should stop appealing to them for help. But if litigation sometimes has positive—even if complex—effects, then it may remain a promising avenue for pursuing policy changes whose prospects are otherwise quite limited. The original edition of The Hollow Hope (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 1991) sparked a vigorous debate in the sociolegal literature, and from the beginning, one of the chief complaints has been that Rosenberg's account of social change conveyed a sense of inevitability that obscured the contingencies of human history (Reference McCannMcCann 1992, Reference McCann1996; Reference GarrowGarrow 1994). Reference RosenbergRosenberg (1991:169) and Reference KlarmanKlarman (2004:468; 1994:14) each argue that mid-twentieth-century racial progress would have occurred regardless of the actions of judges and lawyers, and in their recent work, they have each extended this causal narrative to the gay rights context. Klarman emphasizes that “[t]he demographics of public opinion on issues of sexual orientation virtually ensure that one day in the not-too-distant future a substantial majority of Americans will support same-sex marriage” (2005:484–5), and Reference RosenbergRosenberg likewise details the increasing public acceptance of gays and lesbians, as evidenced by public opinion polls, legislative change, the policies of leading corporations and professional associations, and the representation of gays and lesbians on television and in movies (2008:407–15). They each argue that discrimination against gays and lesbians has decreased in recent decades, but that “these changes are not primarily the result of litigation. Rather, they are the result of a changing culture” (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:415; see also Reference KlarmanKlarman 2005:484–5; Reference D'Emilio and HirschD'Emilio 2005:12, Reference D'Emilio2006:10–11).

Treating law and culture as wholly separate independent variables, these accounts fail to adequately explore the causal significance of the litigation campaigns. Rosenberg is surely correct that the television shows Ellen and Will & Grace have helped make LGBT persons more visible and less hated than before, but it is not clear why he treats this claim as mutually exclusive with the proposition that SSM lawsuits have helped make LGBT persons more visible and less hated than before. Likewise, it is certainly true that controversial court decisions sometimes provoke immediate and hostile political reactions, but even then, their long-term causal implications tend to be complex and multidirectional. Unpacking these causal dynamics can be difficult, but the alternative is to accept an overly simple set of causal attributions. Throughout the Clinton and Bush eras, the legal and political conflicts over LGBT rights have been highly decentralized, with multiple simultaneous battles proceeding in various state judiciaries, 12 federal circuits, and at times the Supreme Court, the White House and the governors' mansions, the halls of Congress and the state legislatures, and in about half the states, the direct democracy process as well. As Smith has argued at some length, this sort of institutional fragmentation has slowed the pace of LGBT rights progress in the United States, contributing to a constant and complex pattern of starts and stops, advances and retreats, successes and failures (2008:182). Amidst this configuration of causal forces, however, there are a variety of mechanisms by which litigation and court decisions have sometimes produced meaningful change.

Most directly, court orders are sometimes effectively implemented. In at least 20 states, for example, litigation led directly to the decriminalization of consensual sodomy, with a long series of state-court victories from 1990 to 2002, followed by the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark 2003 decision in Lawrence. Similarly, while much has been made of the political reaction to judicial decisions expanding partnership rights, state officials have complied with the vast majority of those decisions, including the widely noted cases legalizing SSM or civil unions (CUs) in Vermont, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and California, as well as a number of state court decisions expanding partnership rights in smaller ways.Footnote 1

Even where advocates have relied primarily on legislative strategies, litigation has sometimes been necessary to remove legal barriers to such legislative change. For example, LGBT rights advocates have won statutory protections against employment discrimination in 20 states, along with similar protections in a number of local jurisdictions. Each of these policy changes was the result of legislative action, but in at least one state, such legislative action was constitutionally precluded until the Rehnquist Court's 1996 decision in Romer v. Evans. By persuading the High Court to invalidate the Colorado constitutional provision prohibiting such antidiscrimination protections, LGBT rights litigators enabled the state's legislature to adopt these protections a decade later. If not for this decision, moreover, opponents of gay rights would have replicated Colorado's Amendment 2 in other states, and it is likely that the effort to enact antidiscrimination protections via democratic means would have been closed off in a substantial portion of the country.

Less directly, but no less significantly, successful instances of rights-claiming often heighten expectations that further change is possible, particularly by “altering the expectations of potential activists that already apparent injustices might realistically be challenged at a particular point in time” (Reference McCannMcCann 1994:89; see also Reference GarrowGarrow 1994). In this regard, as Eskridge has argued, the Baehr decision “contributed to the politics of recognition by stirring the aspirations of GLBT people everywhere in the country” (Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:3). Indeed, every judicial decision expanding marriage rights for same-sex couples has inspired more couples to claim such rights. The courtroom victories in Hawaii sparked further litigation in Alaska and, even more important, political organizing followed by further litigation in Vermont (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:183–4, 197–8). In turn, the courtroom victory in Vermont sparked the litigation that led to Goodridge (2003), with Mary Bonauto of Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders (GLAD) serving as lead attorney in both New England cases. And the most immediate and widespread reaction to Goodridge was not opposition, but mass public action by supporters, with thousands of same-sex couples holding public weddings in almost every region of the country. Drawing on interviews with 50 such couples, Pinello argues that Goodridge led to a significant increase in political participation among LGBT persons. Indeed, the decision “had a profound inspirational effect for the marriage movement, among elites and the grass roots …. Time and again, same-sex couples volunteered in interviews across the nation that they never expected marriage to be available to them during their lifetimes. Yet Goodridge opened a floodgate of heightened expectations” (2006:190–3).

In addition to heightening expectations among supporters, legal mobilization can sometimes transform the agenda of the nation's lawmakers as well. Before the 1993 Baehr decision, no state legislature had passed even a limited domestic partnership bill; the vast majority were unwilling even to consider the issue. But the decision had what Eskridge calls an “agenda-seizing” effect (2002:3), fueling the efforts by advocates on both sides and drawing the broader public's attention as well. McCann has demonstrated that “[o]ne key to effective legal mobilization as a movement building strategy [is] the tremendous amount of mainstream media attention generated by dramatic … lawsuits” (Reference McCannMcCann 1994:58), and Rosenberg documents an exponential increase in media coverage of SSM from 1980 to 2004 (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:382–400). Rosenberg argues that the rise in coverage was driven more by the political reaction to the litigation than by the litigation itself, but even so, the litigants had launched a process that transformed the issue from one that lawmakers everywhere were ignoring to one that was firmly placed on the nation's agenda. Once there, of course, SSM advocates lost many of the legislative battles to come, but they won some battles too, with elected legislators in 12 states voting to expand the legal rights of same-sex couples between 1997 and 2008.

One reason lawmakers became increasingly willing to expand partnership rights after Baehr is that the Hawaii decision immediately changed domestic partnership policies from radical, cutting-edge proposals to moderate compromises (Reference DupuisDupuis 2002:92; Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:237). In other words, by pushing the policy envelope, ambitious litigation can clear space for legislative progress in its wake. In Hawaii itself, the 1993 Baehr decision led to the state's 1997 Reciprocal Beneficiaries Act, which fell far short of full equality but nonetheless granted gay and lesbian couples more legal rights than anywhere else in the nation at the time. Asking for too much, too soon is sometimes counterproductive, but aggressive demands can also shift the spectrum of compromise in valuable ways. In this sense, every state legislature that has expanded partnership rights has done so in the shadow of the ongoing litigation campaign. The operation of this causal mechanism does not require judges to persuade or enlighten legislators who were once opposed or blinded, though Reference EskridgeEskridge (2002) and Reference PinelloPinello (2006) have documented several instances in which that appears to have occurred. The mechanism simply requires judges to provide political cover for legislators to declare their support for a policy that they previously considered too great a political liability. In this regard, it is no coincidence that a steady stream of state legislatures has enacted antidiscrimination laws while the SSM conflict has proceeded in the courts. Opponents of gay rights once fought these policies tooth and nail, but compared to equal marriage rights, the prohibition of employment discrimination now seems significantly less threatening.

Even when they spark substantial opposition, moreover, court decisions can change the policy status quo in ways that are difficult to reverse. As Reference SmithSmith (2008) has argued, LGBT rights have progressed more rapidly in Canada than in the United States in part because of the greater degree of centralized authority in Canada's parliamentary system. But once gay rights advocates have won a policy victory in the United States, the famously gridlocked American lawmaking process begins to work in their favor. Before Baker (1999) and Goodridge (2003), SSM opponents in Vermont and Massachusetts needed only to block legislative proposals to expand partnership rights, while SSM supporters had to run the gauntlet of legislating in a system of separated powers. After the decisions, those positions were reversed.

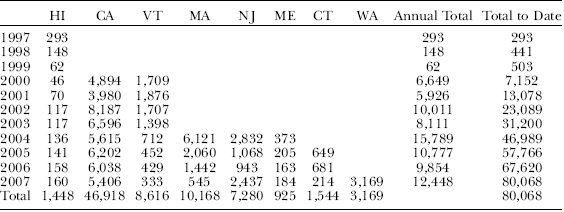

In addition to reversing the relevant veto points, these decisions immediately created a group of people with a vested interest in defending the new, legally recognized same-sex partnerships. In the first eight months of SSM in Massachusetts, more than 6,000 gay and lesbian couples married, and many of these 12,000 citizens subsequently expended significant political effort to defend their existing marriages (see Table 4 ahead). Once these marriages were in place, moreover, it became more difficult for opponents to maintain that they would have severely negative social consequences. In a development that SSM advocates predicted, by spring 2005, the vast majority of Massachusetts residents indicated to pollsters that SSM had had no negative impact on the quality of life in the state (Reference GarrowGarrow 2004; Reference AdamsAdams 2005).

In a variety of ways, then, judicially crafted policies can have significant self-reinforcing effects. By compelling compliance, removing barriers to legislative change, heightening expectations, forcing the issue, pushing the policy envelope, providing an excuse for sympathetic or apathetic legislators, reversing the relevant veto points, and creating new constituencies inspired to claim and defend their rights, even unpopular judicial decisions can prove difficult to dislodge. With these causal mechanisms in mind, I turn now to an examination of the broad patterns of legal and political change affecting LGBT rights from May 1993, when the Hawaii Supreme Court first threatened to legalize SSM, through November 2008. In the course of this examination, I assess the degree to which these patterns are consistent with three principal claims advanced by backlash proponents: (1) that judicial victories have regularly been followed by political defeats, (2) that the end result has been regressive policy change, and (3) that some other strategic choice would have worked better.

The Political Reaction

As I have noted, backlash proponents argue that judicial victories are almost always followed by electoral setbacks. This claim is true but partial, as judicial victories are sometimes followed by electoral gains as well. On both counts, the causal relationship between the court decisions and the subsequent developments is complex, but if the judges and litigators are to be blamed for everything bad that follows their decisions, they may deserve some credit for the good things that follow as well.

With respect to the initial round of litigation in Hawaii, Rosenberg's and Klarman's primary emphasis has been the negative legislative response in Congress and the state capitols—a policy reaction that I examine below—but there were some clear electoral consequences as well. These electoral consequences were mostly, but not entirely, negative. The 1993 Baehr decision came down in the midst of a period of heavy use of ballot initiatives by opponents of gay rights. This strategy had succeeded in Colorado the previous year and was rapidly proliferating nationwide. The chief electoral impact of Baehr was to add SSM bans to the list of antigay policies that were regularly included in these initiatives. The fact that the Hawaii and Alaska electorates voted by significant margins to reverse pro-SSM judicial decisions was certainly a setback for the movement, as were the large number of antigay initiatives adopted at the municipal level during this period. Often overlooked are the electoral defeats of antigay initiatives in Idaho, Oregon, and Maine, but the balance is clearly negative on the whole, as indicated by the top row of Table 1.

Table 1. Electoral Aftermath of Judicial Victories

Note: DP=domestic partnership.

Sources: Reference AndersenAndersen (2005); Lesbian/Gay Law Notes (1994–present; http://www.qrd.org/qrd/www/legal/lgln).

In Vermont, the local legislative reaction to the high court ruling was positive, but backlash proponents have emphasized the subsequent electoral setbacks that occurred (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:344–7). On this account, the Baker decision (1999) forced Vermont's legislators to take a politically unacceptable position, and those legislators paid for it at the polls. As Eskridge has noted, the fall 2000 statewide elections were “conducted in significant part as a referendum on civil unions” (Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:81), and 16 incumbent legislators who supported the civil union bill were unseated (Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:80–2; Reference PinelloPinello 2006:33; Reference RobinsonRobinson 2001). This electoral backlash was real, but its severity should not be overstated. The state house switched hands from Democratic to Republican, and from pro–civil union to anti-, but the senate and governor's mansion remained in the hands of civil union supporters. The Democratic governor who signed the civil union bill was reelected handily, as was the Democratic lieutenant governor, who supported full marriage equality. Democrats who supported the civil union bill were elected secretary of state and state auditor as well. The only statewide race won by the GOP was for the U.S. Senate, where incumbent Senator Jim Jeffords bucked his party to support the civil union bill, was reelected in a landslide, and then quit the Republican Party a few months later.

The local electoral reaction to the 2003 Goodridge decision was even more striking. As Massachusetts legislators considered their options, there was much discussion about the electoral costs that their colleagues had suffered in Vermont just three years earlier. But this time around, SSM advocates successfully fended off all seven primary challenges faced by their legislative supporters in 2004, while unseating two incumbents who opposed SSM and picking up three open seats as well. SSM supporters picked up three additional seats in special elections held in early 2005, and in 2006, they captured the governor's mansion as well, with SSM supporter Deval Patrick elected to succeed SSM opponent Governor Mitt Romney (Reference BonautoBonauto 2005; Reference PinelloPinello 2006:45–72). In sum, once Goodridge's dust had settled, the state's elected institutions were significantly more supportive of SSM than they had been at the outset. These electoral gains enabled SSM advocates to defeat multiple constitutional amendments designed to reverse the Goodridge decision, culminating in a June 2007 vote in which SSM opponents were unable to persuade even one-quarter of the state legislators to keep their proposed amendment alive. Contemporaneous accounts attributed this final victory for Goodridge to heavy lobbying by the national gay rights groups and the state Democratic leadership, as well as influential pressure from the legislators' married gay constituents (Reference BelluckBelluck 2007; Reference Phillips and EstesPhillips & Estes 2007; Reference Wangsness and EstesWangsness & Estes 2007).

The nationwide electoral impact of Goodridge was more complex, but it was far from uniformly negative. The most direct result was that voters in 16 states enacted anti-SSM constitutional amendments in 2004, 2005, and the first half of 2006. These amendments represented significant policy setbacks for SSM advocates, and they may have had broader electoral consequences as well. Klarman emphasizes that they were approved by such large margins—the median vote share for these 16 proposals was 73.9 percent—that they represented a stinging popular rebuke of the Massachusetts judges, and Klarman and Rosenberg each argue that the presence of these amendments on state ballots in November 2004 contributed to President Bush's reelection and the GOP's pickup of four additional seats in the U.S. Senate. Since President Bush and the Republican Senate subsequently named then-Judges John Roberts and Samuel Alito to the Supreme Court, Klarman suggests that SSM litigators may bear responsibility for entrenching a conservative judicial majority as well (2005:468).

In drawing out these electoral implications, Rosenberg and Klarman each rely more heavily on the post-election spin advanced by SSM opponents than on the leading accounts of the election by professional political scientists. They each note that Republican political adviser Karl Rove “appeared to stifle a grin” when asked whether he was “indebted” to the Massachusetts high court; they each quote Robert Knight's observation that “President Bush should send a bouquet of flowers” to Massachusetts Chief Justice Margaret Marshall; and they each emphasize the widely noted exit poll in which 22 percent of voters indicated that “moral values” was the most important issue facing the nation (Reference KlarmanKlarman 2005:467, 482; Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:370, 376). One of the leading scholars of American elections and public opinion has argued that the widespread attribution of President Bush's reelection to Goodridge is substantially misleading, but neither Rosenberg nor Klarman addresses his arguments (Reference Fiorina, Abrams and PopeFiorina et al. 2006:145–57; see also Reference Hillygus and ShieldsHillygus & Shields 2005; Reference EganEgan & Sherrill 2006). Nonetheless, the backlash proponents are certainly correct that the Goodridge decision was polarizing and unpopular and that the national Republican Party stoked this unpopularity with some success in November 2004. Rove and his fellow Republican operatives helped place anti-SSM amendments on the ballot in key swing states, and those initiatives may have aided Republican candidates up and down the ballot. Taken together, Rosenberg and Klarman make a strong case that the Massachusetts decision contributed to President Bush's victories in Ohio and Iowa and to GOP Senate victories in Kentucky, Oklahoma, and South Dakota (Reference KlarmanKlarman 2005:467–70; Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:369–82).

But while the Goodridge decision clearly mobilized opponents of SSM, it seems to have mobilized supporters as well. In February 2004, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom responded to President Bush's recent denunciation of the “activist judges” of the Massachusetts court by announcing that city officials would begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Within weeks, 4,000 such couples had married in the streets of San Francisco, drawing nationwide front-page coverage and inspiring a variety of copycat efforts, with 3,000 marriages performed by public officials in Portland, Oregon, and similar but smaller actions in Asbury Park, New Jersey; Sandoval County, New Mexico; and New Paltz, New York (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:235–6; Reference MezeyMezey 2007:109–13). In short, the Goodridge decision sparked a wave of mass action to claim the rights that the Massachusetts court had promised. Rosenberg and Klarman emphasize that Mayor Newsom's actions provoked yet more backlash, but again, those actions seem to have inspired supporters as well as opponents. In particular, they encouraged more same-sex couples to claim their rights and more public officials to support those claims. In addition to the copycat actions by local executive officials, the controversy led to a nationwide wave of new SSM lawsuits, with the leading national LGBT rights organizations filing state constitutional challenges in Connecticut, Florida, Maryland, New York, Oregon, and Washington during the spring and summer of 2004. Mayor Newsom's actions also drew the litigators into such a challenge in California, and Lambda Legal continued to pursue the state constitutional challenge it had filed in New Jersey in 2002. Most of these lawsuits eventually ended in defeat—although even these, as I note below, often sparked legislative progress—but three of them resulted in landmark victories. In New Jersey, California, and Connecticut, the state legislature voluntarily expanded partnership rights while the legal challenges were pending, but in each case, the state high court held that the existing policies did not go far enough. In October 2006, the New Jersey Supreme Court ordered the state to provide same-sex couples with all the legal rights and benefits of marriage; a year and a half later, the California Supreme Court ordered the state to provide same-sex couples with access to marriage itself; and five months after that, the Connecticut Supreme Court followed California's lead (Lewis v. Harris 2006; In re Marriage Cases 2008; Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health 2008).

The New Jersey and Connecticut victories are particularly notable for causing no discernible electoral backlash. Lewis v. Harris (2006) came down two weeks before the nation's congressional elections, including a close Senate race in New Jersey, but it had no apparent electoral spillover, either locally or nationally. Civil union supporter Robert Menendez won the Senate race, helping the Democratic Party to capture both houses of Congress for the first time in 12 years, and unlike 2004, the national exit polls revealed little evidence that SSM was a key issue, despite the presence of anti-SSM initiatives on the ballot in eight states (Reference EganEgan & Sherrill 2006). In a landmark development, one of these initiatives was defeated, receiving support from just 48.2 percent of Arizona voters, and in contrast to 2004, only two of the eight received more than 70 percent support. The Connecticut decision likewise came down shortly before a national election, and likewise seemed to have little effect. Some SSM opponents in the state urged the public to support an already-existing ballot measure calling for a convention to propose amendments to the state constitution, but 59 percent of the state's voters rejected the proposal, and the high court's decision took effect shortly after the election.

In contrast, the California Supreme Court's May 2008 marriage decision was reversed at the polls, with 52 percent of the state's voters supporting an anti-SSM constitutional amendment on November 4, 2008. This vote represented a major setback for the LGBT rights movement, a setback compounded by the voters' enactment of anti-SSM amendments in Arizona and Florida on the same day, as well as a ballot measure banning unmarried couples from fostering or adopting children in Arkansas. Notably, however, the California vote does not appear to have ended the long-running campaign for SSM in the state. To the contrary, SSM supporters have responded with dozens of protests throughout the state, a novel and probably long-shot legal challenge to the amendment, and plans for an initiative campaign to re-amend the state constitution, perhaps as early as 2010 (Reference GarrisonGarrison 2008). Given the increasing public support for SSM in the state—voter opposition to the state's two anti-SSM initiatives increased from 38.6 percent in 2000 to 47.8 percent in 2008, and according to the 2008 exit polls, it reached as high as 61 percent among 18- to 29-year-old voters—it seems likely that the final word has not yet been heard.1

The available polling data indicate a similar pattern of increasing public support for SSM nationwide. As indicated in Table 2, national polls conducted since Goodridge almost always find at least 30 percent support for SSM and on several occasions have found support exceeding 40 percent, marking an unambiguous increase over pre-Baehr levels. Public support for extending the legal rights of marriage without the name has increased even more dramatically. Finding a pre-Baehr baseline for comparison on this point is difficult—polling on “civil unions” did not occur until the concept was invented in Vermont in 2000—but Rosenberg has identified some early polls that provide close approximations. As indicated in Table 3, when a 1989 Gallup poll asked whether “homosexual couples [should] have the same legal rights as married couples,” only 23 percent of respondents said yes. In the wake of the Vermont decision, Gallup found 40 percent support for the proposition that “gay partners who make a legal commitment to each other should … be entitled to the same rights and benefits as couples in traditional marriages,” and after Goodridge, Gallup found support as high as 56 percent for “allow[ing] homosexual couples to legally form civil unions, giving them some of the legal rights of married couples.” Rosenberg also cites a 1991 poll conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates (PSRA) in which 39 percent of respondents indicated that homosexual couples should “be able to get the same job benefits as a married couple” (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:405). After Goodridge, Newsweek found 60 percent support for “health insurance and other employee benefits for gay spouses,” and other polls with different question wording have found support ranging from 40 to 54 percent.

Table 2. Public Support for Same-Sex Marriage

Note: Poll results in regular typeface are from Rosenberg (2008:400–7); those in bold were compiled by the author. NORC/GSS is the National Opinion Research Center's General Social Survey.

Table 3. Public Support for the Legal Rights of Marriage Without the Name

Note: CU=civil unions. Poll results in regular typeface are from Rosenberg (2008:400–7); those in bold were compiled by the author (from publicly available online sources, most of them from http://pollingreport.com/civil.htm). PRSA is Princeton Survey Research Associates.

The breadth of public support for granting same-sex couples the legal rights of marriage is most clearly indicated by polls providing respondents with the full range of policy options: that is, asking whether they support SSM, civil unions, or no legal recognition for same-sex couples. As indicated in the bottom half of Table 3, aggregating the public support for SSM and civil unions in these polls makes clear that a position that “would have been considered a utopian gay fantasy” at the outset of the litigation campaign—that same-sex couples should have access to all the legal rights and benefits of marriage—now receives consistent support from popular majorities (Reference Hirsch and HirschHirsch 2005:ix; see also Reference EganEgan & Sherrill 2005b; Reference PersilyPersily et al. 2006:43–4). Evan Wolfson, Mary Bonauto, and their fellow LGBT rights litigators probably deserve some credit for this increased support. At the very least, they should not be blamed for increasing public opposition to gay rights, because no such increase has occurred.

The Policy Impact

Even if the general public has not turned against gay rights, the courtroom victories may have provoked regressive policy change—that is, legislative actions that left LGBT rights advocates worse off than they were at the beginning. In support of this claim, backlash proponents repeatedly emphasize that 45 states have banned the recognition of SSM, with 27 of those states enshrining the ban in their state constitutions.Footnote 2 The Utah legislature was the first to act, clarifying its own rules for marriage eligibility just months after the Baehr decision in 1993 and prohibiting the recognition of out-of-state SSMs two years later. As a number of states considered similar measures, Congress declared in the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) that the federal government would not recognize SSMs and that each state was free to refuse recognition as well. “Long after the current homophobic panic is over,”Reference D'Emilio, Rimmerman and WilcoxD'Emilio notes, “these DOMA statutes and state constitutional amendments will survive as a residue that slows the forward movement of the gay community toward equality” (2007:61; see also Reference KlarmanKlarman 2005:466; Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:416).

This claim implies a greater degree of policy retrogression than has actually occurred. No state recognized SSM prior to the onset of litigation, so the statutory bans effected no actual change of policy. The constitutional bans have made it more difficult for SSM advocates to achieve their desired policy change, but in the vast majority of these 27 states, the odds that either the legislature or the courts would have legalized SSM were pretty low from the beginning. If and when SSM comes to states such as Alabama, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas, it is likely to be the result of a federal judicial order, and state constitutional prohibitions will not stand as a bar to such federal legal action.Footnote 3

In 17 of these 27 states, the policy setback was somewhat worse, as the language of the constitutional ban either clearly or potentially prohibits state recognition of civil unions and domestic partnerships as well as SSM. Many of these 17 states were unlikely to recognize such statuses anyway, but in at least eight of them, the constitutional ban has rendered some existing policies legally vulnerable. Prior to the recent amendments, at least one local jurisdiction or state agency (such as a public college) in Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin provided domestic partnership benefits to its employees. In four of these states, at least one local jurisdiction maintained a domestic partnership registry for local residents as well.Footnote 4 The full legal effect of the anti-SSM amendments on these policies is not yet clear, but the Michigan Supreme Court has already held that public employers in the state can no longer offer domestic partnership benefits, and it is likely that LGBT residents of the other seven states will face similar threats to their existing rights and benefits.Footnote 5 The scope of these existing rights is quite narrow—none of these states had anything approaching a statewide marriage law—but for the affected couples, the deprivation (or potential deprivation) may well have significant adverse consequences.

These concrete policy setbacks, however, should be weighed against the concrete policy advances that have occurred during the same period. Most directly, tens of thousands of same-sex couples have won access to legal rights and economic benefits that they did not have before. Beginning with Hawaii, every state in which a court has ruled in favor of expanded partnership rights for same-sex couples has indeed subsequently seen an expansion of such rights. None of these expansions represent full victories for SSM advocates, but in every state, there has been progress rather than retrogression. Several additional states have expanded partnership rights in the absence of a court order, and most if not all of these policy changes are at least partly attributable to the ongoing litigation campaign.

All told, since the Hawaii suit was filed, 10 states and the District of Columbia have created a legal status, similar to marriage, which same-sex couples may choose to enter.Footnote 6 The specific rights and benefits attached to these alternative legal statuses vary from state to state, but even the narrowest policies provide certain crucially important rights that legal spouses take for granted, such as the right to own property jointly, to make medical decisions for one another, and to inherit property and receive life insurance benefits in the event of a partner's death. Seven states provide same-sex couples with all or virtually all of the state law rights and benefits of marriage, including parental rights. Given the importance of such rights and benefits, it is no surprise that more than 80,000 couples have chosen to take advantage of them, as indicated in Table 4. An even greater number of same-sex couples have benefited from the rapid proliferation of employer-provided domestic partnership policies that has coincided with the SSM litigation campaign. When the Baehr decision came down in 1993, only a handful of private employers offered such policies; by 2008, more than 8,000 did so. Among Fortune 500 corporations, the number providing such benefits rose from 10 in 1993 to 270 in 2008.Footnote 7 In the public sector, no states provided domestic partnership benefits to their own employees until 1994; by 2008, 15 states (and the District of Columbia) did so (ibid.).

Table 4. Number of Same-Sex Marriages, Civil Unions, and Domestic Partnerships by State

Note: Not included in this table are the District of Columbia, which has maintained a domestic partnership registry since 2002; and New Hampshire and Oregon, whose civil union and domestic partnership policies took effect in early 2008. The numbers reported for California, Hawaii, and Washington are marginally inflated, as their domestic partnership or reciprocal beneficiary statuses are each open to certain strictly defined adult family relationships other than same-sex couples.

Many of these policy changes resulted directly or indirectly from litigation. In California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Vermont, state lawmaking institutions complied with judicial decisions ordering expanded partnership rights. In Hawaii, the legislature helped reverse such a decision, but simultaneously granted some of the rights that the litigants had sought. In California, Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, lawmakers expanded partnership rights while an SSM lawsuit was pending in the state's courts. In each of these states, elected legislators were relatively supportive of LGBT rights before the SSM suit was filed, but they were unwilling to expand partnership rights until they had the political cover provided by the legal challenge. In Oregon and Washington, legislators ducked the issue while litigation was pending—perhaps hoping the courts would take the hot potato off their hands—but stepped in once the judges refused to do it for them. In other words, they responded to recently concluded lawsuits by voluntarily extending some of the legal rights that same-sex partners had unsuccessfully sought in court. Only in Maine and New Hampshire have legislators significantly expanded partnership rights in the absence of local litigation, and even there, they surely did so at least in part because the prior, litigation-prompted policy changes in neighboring states had raised the expectations of local gays and lesbians.

The expansion of workplace domestic partnership benefits has generally been less directly tied to litigation, but here too, legal mobilization has played a role. Alaska, Montana, and Oregon have each extended domestic partnership benefits to public employees as a result of court orders, and even those employers who have adopted such policies in response to other forms of pressure have surely been influenced by the pervasive litigation on this issue since Baehr. After all, it was the SSM lawsuits that first drew public attention to the difficulties faced by gay and lesbian couples in accessing health insurance and other spousal benefits, and it was the lawsuits that transformed workplace domestic partnership policies from a cutting-edge proposal in the early 1990s to the moderate compromise they represent today.

SSM advocates have repeatedly supported such compromise policies as important steps toward their goal of full marriage equality. Most SSM advocates endorsed the civil union proposal during the pivotal Vermont legislative debates of 2000, and as Eskridge has argued at some length, this sort of incremental policy change has often been followed by subsequent expansion (Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002; see also Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:184–8; Reference RobinsonRobinson 2001). In California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, Washington, and the District of Columbia, SSM advocates succeeded in enacting some limited statewide recognition of same-sex relationships and subsequently expanding the range of legal rights and benefits offered to such couples. As I have noted, moreover, all this legislative progress has occurred in the shadow of the ongoing litigation campaign.

Examining partnership rights as part of a broader continuum of LGBT rights issues, Reference EskridgeEskridge (2000) paints an even clearer picture of incremental policy change over time. Beginning in the 1970s, states have tended to reform their regulations of gays and lesbians in the following sequence: decriminalizing consensual sodomy, establishing protections against hate crimes, prohibiting discrimination in the workplace (and sometimes in public accommodations), establishing some minimal legal recognition for same-sex partnerships (particularly at the municipal level), and then expanding the scope of that recognition in a series of steps toward full marriage equality. Backlash proponents often claim that premature litigation efforts have the effect of derailing a movement's more cautious campaigns through democratic institutions, but this incremental pattern of state-level policy change has continued without significant interruption—and may even have accelerated—during the period of active SSM litigation.

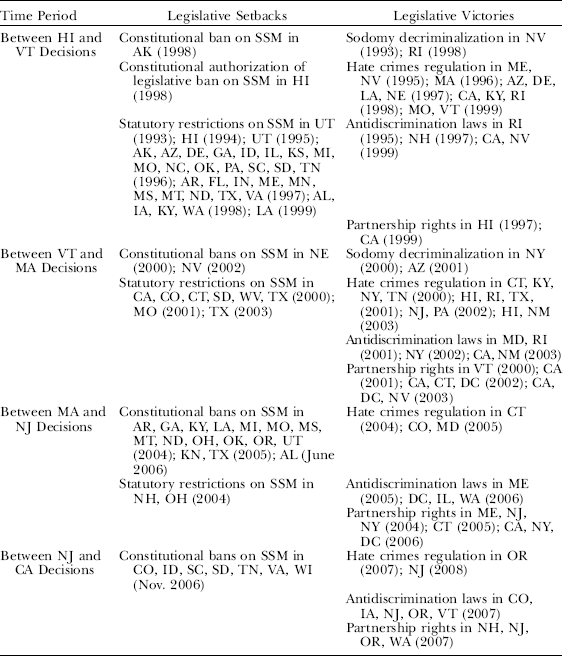

Consider the state-level policy changes on four leading LGBT rights issues in the wake of the courtroom victories in Hawaii, Vermont, Massachusetts, and New Jersey, as summarized in Table 5. In the six years following the Baehr decision, only two state legislatures repealed their criminal sodomy laws, but this progress was no slower than it had been in the years leading up to Baehr. Twenty state legislatures had repealed their sodomy laws in the 1970s and early 1980s—generally as part of a wholesale adoption of the Model Penal Code—but this wave of legislative reform had run its course by 1983 (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:60–72). Likewise, the willingness of state courts to invalidate criminal sodomy laws appears to have been unaffected by the Hawaii decision. If anything, they became more willing after the decision than before, with courts in Michigan and Kentucky doing so in the early 1990s and courts in Tennessee, Montana, Georgia, and Maryland doing so in the late 1990s. On the issue of hate crimes regulation, there had been somewhat more legislative progress prior to Baehr, but this progress continued after the decision. From May 1993 through the end of 1999, 12 states expanded their hate crimes protections for LGBT persons. Only Hawaii and California extended formal legal recognition to same-sex partnerships during this period, but since no states had done so prior to Baehr, this level of activity represented a positive change. On only one key legislative priority of LGBT rights advocates did the Hawaii decision appear to stall forward progress. In the two years preceding Baehr, six states had amended their antidiscrimination laws to expand protections for LGBT persons; in the six years following it, only Rhode Island, New Hampshire, California, and Nevada did so.

Table 5. State-Level Legislative Change After Judicial Victories

Note: Some states are listed more than once under the same legislative subject because they enacted more than one relevant legislative expansion or contraction of LGBT rights. For example, some enacted hate crimes laws covering sexual orientation and subsequently expanded those laws to cover gender identity, while others have repeatedly expanded or contracted the range of legal rights offered to same-sex couples. Under antidiscrimination laws, I have included only those that prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation and/or gender identity in private employment. Many of these states also ban such discrimination in public employment and public accommodations, and some do so in public schools as well.

Sources: Reference EskridgeEskridge 1999, Reference Eskridge2000; Lesbian/Gay Law Notes (multiple issues; see sources for Table 1).

The pattern of legislative change in the wake of Baker v. State of Vermont (1999) was similar. The legislatures of Arizona and New York repealed their states' criminal sodomy statutes (as did courts in Arkansas, Massachusetts, and Minnesota), and 10 states enacted or expanded laws covering hate crimes against LGBT persons. The hate crimes laws represented a nationwide legislative response to the October 1998 murder of Matthew Sheppard in Wyoming, but the December 1999 marriage decision from the Vermont Supreme Court does not appear to have slowed this response. In addition, California, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Rhode Island extended their antidiscrimination laws to cover sexual orientation and/or gender identity; the District of Columbia joined Vermont in extending formal legal recognition to same-sex couples; Connecticut extended some minimal legal rights to unmarried couples and commissioned a study to assess options for providing further such rights; and California repeatedly expanded the range of legal rights provided to domestic partners, culminating with a 2003 statute extending all state law rights and responsibilities of marriage. Again, none of this progress came quickly, but it was no slower than it had been prior to the onset of SSM litigation.

In the wake of Goodridge (2003), the pace of antigay legislation picked up considerably, but the pace of pro-gay policy change picked up as well. Just prior to Goodridge, the Lawrence decision (2003) had decriminalized sodomy in the 13 states that had not yet done so, thus removing this issue from the LGBT legislative agenda. Most states had already made at least some legislative response to antigay violence by this point as well, but three states extended their hate crimes laws during this period, and three states and the District of Columbia extended their antidiscrimination laws. Anecdotal evidence indicates that the post-Goodridge backlash made some state legislators more reluctant to enact gay rights policies, but these barriers have not proven insuperable. In Illinois, for example, early reports blamed the Massachusetts decision for sinking a then-pending antidiscrimination bill, but the legislature enacted an even stronger bill three years later (Reference BrownBrown 2003). During this same period, the elected institutions in five states and the District of Columbia expanded the range of partnership rights provided to same-sex couples.

Following the 2006 decision in Lewis v. Harris, LGBT rights advocates witnessed the most remarkable year of legislative success in the entire history of the movement. In 2007 alone, Oregon extended its existing hate crimes law to cover gender identity, and Colorado, Iowa, New Jersey, Oregon, and Vermont extended their antidiscrimination laws, marking a significant acceleration of legislative progress on this issue. In addition, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Oregon extended the full range of spousal rights and benefits to same-sex couples, and Washington extended a substantial list of such rights as well. It is too soon to assess the full policy impact of the California marriage decision. The state's voters reversed the decision in November 2008, but the legal status of the approximately 18,000 SSMs that were performed prior to Election Day remains unclear. Elsewhere, SSM advocates continued their legislative progress from the year before. Washington expanded the list of legal rights extended to domestic partners, as did the District of Columbia. New York Governor David Paterson directed all state agencies to recognize lawful SSMs from other jurisdictions, and Massachusetts repealed the residency requirement that had prevented most out-of-state same-sex couples from marrying there. Massachusetts also extended Medicaid benefits, at state expense, to same-sex spouses who were ineligible for federally funded benefits, and Missouri authorized same-sex partners to designate one another to make decisions regarding the disposition of remains in the event of one of their deaths. None of these policy changes received as much national media attention as the anti-SSM initiatives enacted in November, but they are not insignificant.

Table 6 summarizes the overall pattern of state-level policy change from May 1993, when the Baehr decision came down, through November 2008. At the outset, 23 states still criminalized consensual sodomy, as did the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico; no state does so today. Only 11 states had laws addressing hate crimes on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity; 32 states have such laws today. Only eight states prohibited private employers from firing a worker on the basis of his or her sexual orientation, and only one did so on the basis of gender identity; today, those numbers are 20 and 12, respectively. No state provided any legal recognition or economic benefits to same-sex partnerships, and only a small number of local jurisdictions did so. Today, 15 states provide health care benefits to the same-sex partners of their own employees, with 11 of them extending some broader set of legal rights to same-sex couples as well.

Table 6. State-Level LGBT Rights Policies, 1993–2008

Compared to What?

Despite these policy victories, backlash proponents repeatedly charge that SSM advocates have been lured by the “myth of rights” to adopt a suboptimal strategy. In a concluding section of his 2008 chapters on SSM, titled “When Will They Ever Learn?” Rosenberg complains that if SSM advocates had read his book, they “could have foreseen the negative reaction to the Hawaii litigation” and they would have avoided “succumbing to the ‘lure of litigation’” (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 2008:419). Instead, as with so many other left-liberal movements since the mid-twentieth century,

the liberal agenda was hijacked by a group of elite, well-educated and comparatively wealthy lawyers who uncritically believed that rights trump politics and that successfully arguing before judges is equivalent to building and sustaining political movements …. Political organizing, political mobilization and voter registration may not be glamorous, or pay six-figure salaries, but they are the best if not the only hope to produce change. (2008:430–1)

Rosenberg provides no direct evidence that LGBT rights litigators have been so taken in by a civics-book understanding of American courts as to repeatedly ignore what would have been preferable strategies. (Even less does he provide any evidence that the movement litigators are blinded by their own desires for wealth and glamour.) Legal mobilization scholars have long observed that it is difficult to find any actual litigators who have succumbed to the myth that legal rights are magic recipes for instant change, and as Andersen makes clear, the observation holds for LGBT rights advocates. She concludes her study of Lambda Legal by noting that “every litigator” she interviewed was “well aware that the struggle for legal reform does not begin and end in the courtroom” (2005:214–15; see also Reference McCannMcCann 1992:728–9, 1994).

Leaving aside the question of the advocates' motivations, the backlash argument amounts to a series of post hoc judgments that particular instances of litigation were strategically unwise because they provoked more political opposition than some other available strategy would have provoked. In Rosenberg's judgment, strategies that emphasized legislation rather than litigation and incremental rather than radical change would have provoked less opposition and hence been more successful (2008:383, 417). Klarman has likewise emphasized that when gay rights litigators began pushing for SSM in the early 1990s, there was strong public support for the decriminalization of sodomy, the prohibition of employment discrimination, and the extension of limited domestic partnership benefits, but not for SSM. By forcing SSM to the fore, courts (and litigators) undermined the cause (2005:475–7).

In claiming that SSM advocates in the early 1990s should have pursued their goals both more cautiously and more democratically, backlash proponents tend to mis-specify the actual strategic dilemma that these advocates faced. The modern wave of SSM lawsuits was not initiated by the national LGBT rights organizations and could not have been stopped by them. It was initiated by gay and lesbian couples in Hawaii (and elsewhere) seeking health insurance, parental rights, and other legal and financial protections for their families (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:239; Reference ChaunceyChauncey 2004:87–136; Reference Egan and SherrillEgan & Sherrill 2005a; Reference GarrowGarrow 2004). The actual choice faced by movement leaders was whether to join and help shape these efforts or to watch them continue as uncoordinated actions of individual plaintiffs and their private counsel. Since the latter choice would have left the advocacy organizations with no influence over important tactical decisions regarding when and where to file, what to argue, and whether to appeal—and since it might also appear as a significant rebuke of their own members and supporters—all the national LGBT rights organizations eventually signed on. But they did so only when it became clear that the Hawaii case was headed to the state high court with or without them, at which point they concluded that it was unwise to let the courts rule on the issue without having heard from the nation's most knowledgeable and experienced LGBT rights advocates (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:178; Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:16–8; Reference GarrowGarrow 2004; Reference PinelloPinello 2006:23–30). From this angle, in a world of constant litigation by friend and foe, the choice faced by movement leaders is not whether the courts should be involved but whether they should hear your claims before deciding your fate.

Once having joined the fray, moreover, the LGBT rights advocates did not decide to litigate and do nothing else. Like their opponents, these advocates have relied on both judicial politics and democratic politics, making a series of tactical decisions in individual circumstances. Drawing on their earlier experience litigating against criminal sodomy laws and the military ban on service by gays and lesbians, they were well aware of the cautious, incremental, and deferential tendencies of judicial institutions, and they knew full well that their efforts had to proceed on multiple, simultaneous fronts. As such, when the leaders of the LGBT public interest bar signed onto the SSM campaign, they collectively agreed to litigate only where the odds seemed most in their favor and, in the meantime, to devote significant resources to a broader campaign of public education, media relations, and legislative lobbying (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:178–83). These advocates selected Vermont as the site of their first test case, but they held off on launching the suit until four years after the initial Hawaii decision; only then did they conclude that their political organizing had progressed far enough to make a judicial victory sustainable (Reference JohnsonJohnson 2000; Reference EskridgeEskridge 2002:45–8).

Their landmark victory in Baker (1999) seemed to confirm the viability of the test-case strategy, and they moved quickly to identify their next targets. As with Vermont, they sought out states whose courts had been relatively supportive of gay rights (indicating that their legal arguments would get a fair hearing) and whose political cultures were relatively supportive as well (indicating that the strength of any backlash would be relatively contained) (Anderson 2005:219–20; Reference GarrowGarrow 2004). These factors led them to file suit in Massachusetts in 2001 and New Jersey in 2002, with the litigators in each case building on years of local political organizing on behalf of increased partnership rights (Reference BonautoBonauto 2005; Reference PinelloPinello 2006:34–41). Unlike the Hawaii suit, then, the legal battles in Vermont, Massachusetts, and New Jersey were intentionally chosen by the LGBT rights organizations. Each of these lawsuits led to a landmark legal victory, and each of these victories survived the resulting political backlash.

SSM advocates filed a number of other suits that turned out less well, but even there, it is not clear that the strategic decision to file them was wrong. After Baehr (1993), SSM was on the nation's legal and political agendas whether LGBT rights advocates liked it or not. Thus, they no longer had the option of taking the status quo for granted and focusing on something else. The SSM campaign had been launched by same-sex couples acting independently; once launched, the issue was kept on the table by conservative opponents. In Massachusetts, for example, SSM opponents were pursuing a state constitutional amendment well before Goodridge was filed. In this context, LGBT rights advocates could either play defense or open some new fronts of their own. Their opponents were pursuing every available avenue—attacking SSM at the polls, in state and federal legislatures, and in state and federal courts—and it is not clear how a unilateral decision to steer clear of one of these avenues would have helped their cause.

That said, SSM advocates often decided to discourage litigation when the time was not right. Prior to the Hawaii case, movement litigators repeatedly rejected requests to bring SSM lawsuits, and while that litigation was pending, the leading advocates discouraged gay and lesbian couples from filing or continuing SSM lawsuits in Alaska, Arizona, Florida, and New York. After the Baker decision in Vermont, the leading national LGBT rights organizations jointly issued a pamphlet that discouraged precipitous litigation by same-sex couples, and after Lawrence and Goodridge, they discouraged further unplanned litigation in Arizona and Florida. In 2006, the national LGBT rights groups urged the Ninth Circuit to dismiss a constitutional challenge to DOMA, and in 2008, they issued yet another pamphlet discouraging litigation.Footnote 8

The fact that LGBT rights advocates have often decided not to litigate a particular claim at a particular time and place suggests that when they have decided to litigate, it is because they have concluded that such a tactic is more promising than (or complementary to) the available alternatives. As Reference ZackinZackin (2008) has noted in another context, social movements often turn to judicial politics only after democratic politics proves unavailing. In this light, it is noteworthy that prior to the litigation campaign, SSM advocates had made very little progress in state or federal legislative institutions. Several local gay rights organizations were lobbying for statewide domestic partnership policies in the 1990s, but these policies were quite limited in scope, and their advocates were having very little success. The D.C. City Council voted to create a domestic partnership registry in 1992, but Congress blocked the bill from taking effect for another 10 years. The California legislature voted to do so in 1994, but Governor Pete Wilson vetoed the bill. The first such policy to become law was Hawaii's Reciprocal Beneficiaries Act, but that act was the direct result of litigation. Prior to the onset of that litigation, no state legislature was willing to extend even limited partnership rights to same-sex couples.

This legislative unresponsiveness has extended even to issues where the public is broadly supportive of LGBT rights. For at least 30 years—since the Gallup Poll began asking the question in 1977—a majority of the public has agreed that “homosexuals should … have equal rights in terms of job opportunities.” For the past 15 years, the level of support has exceeded 80 percent (see http://www.gallup.com/poll/1651/Homosexual-Relations.aspx). Despite repeated efforts, however, Congress has failed to enact the Employment Non-Discrimination Act. More than 80 percent of the public now thinks that gays and lesbians should be allowed to serve in the military as well, but again, Congress has failed to respond (Reference EganEgan & Sherrill 2005b; Reference MezeyMezey 2007:179–80, 221–2). As noted above, LGBT rights advocates have had more success in banning employment discrimination at the state level, but most of this progress has come in the midst of the SSM litigation campaign. Likewise with sodomy decriminalization, at the time Baehr was filed, the substantial public support for reform was not producing legislative change (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:60–72).

In addition to overstating the degree of legislative progress that had occurred prior to the litigation campaign, backlash proponents generally fail to acknowledge that when LGBT rights advocates did win legislative victories, these victories frequently provoked political backlash. As Lemieux has argued, the backlash thesis rests on a (sometimes implicit) claim that controversial judicial decisions tend to provoke a more severe negative reaction than otherwise similar legislative decisions. Lemieux finds little evidence to support this claim in the abortion context, noting that Roe v. Wade sparked substantial opposition but that the pro-choice movement's earlier attempts at abortion reform via state legislative action had provoked a similar reaction (2004:218–9). The story of conservative countermobilization in response to legislative protections of gay rights is similar, with citizen lawmaking procedures repeatedly used to repeal gay rights policies that have been enacted by elected officials (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:149; Reference MezeyMezey 2007:31–2).

Some episodes of this story are so well-known that it is hard to justify the lack of attention given to them by backlash proponents. As early as 1977, Anita Bryant made national headlines with her campaign to repeal the antidiscrimination ordinance that had been enacted by the Dade County Metropolitan Commission in Florida. The popular singer and advertising icon spearheaded a populist backlash that produced not only a local referendum repealing the ordinance but also a state statute imposing a blanket prohibition on adoptions by “homosexuals.” Signed by the governor just one day after the Dade County referendum, this statute represented a significant retrogression in parental rights for gays and lesbians in Florida (Reference RimmermanRimmerman 2002:127–9). The Bryant campaign sparked several similar efforts in the late 1970s, and once gay rights advocates started winning legislative victories more often, their conservative opponents repeatedly responded with this sort of electoral countermobilization.

The most well-known story took place in Colorado, where a series of state and local lawmakers either enacted or considered proposals to ban discrimination against gays and lesbians in the late 1980s and early 1990s, prompting local leaders of the religious right to launch a campaign to amend the state constitution to prohibit any governmental unit in the state from adopting or enforcing such policies. The state's voters enacted this proposal in November 1992, a result that immediately prompted copycat efforts around the country. Over the next three years, similar bans on antidiscrimination protections reached statewide ballots in Idaho, Maine, and Oregon, and local ballots in more than 30 jurisdictions in Florida, Ohio, and Oregon. Each of the statewide initiatives was narrowly defeated at the polls, but most of the local measures were successful. The LGBT rights movement responded with multiple state and federal legal challenges, raising both procedural and substantive objections to these antigay initiatives. After several preliminary victories in state courts, this litigation campaign culminated in Romer v. Evans, the 1996 Supreme Court decision invalidating Colorado's Amendment 2 (Reference AndersenAndersen 2005:151–2, 253–4, note 13).

Romer v. Evans was a landmark legal victory for the LGBT rights movement, but its precise scope remained somewhat unclear. Opponents exploited this ambiguity by continuing to advance antigay initiatives that were distinguishable from Amendment 2, either because they merely repealed existing antidiscrimination protections (rather than banning their future enactment) or because they applied to a single local jurisdiction (rather than statewide). In a series of initiatives and referenda in Maine, for example, the voters repealed the state's antidiscrimination protections for gays and lesbians in 1998, blocked the reenactment of those protections in 2000, and nearly repealed them again after their legislative reenactment in 2005. At the local level, the frequency of antigay initiatives slowed somewhat after Romer, but opponents of gay rights continued to respond to the legislative enactment (or consideration) of antidiscrimination protections with ballot campaigns designed to repeal (or forestall) those protections. Such measures have reached the ballot in at least eight local jurisdictions since 1996, including Miami-Dade County, in an unsuccessful 2002 rerun of the Anita Bryant campaign.Footnote 9

In similar fashion, the legislative expansion of partnership rights for same-sex couples has repeatedly sparked countermobilization. In at least 28 local jurisdictions since 1993, the actual or prospective expansion of partnership rights by elected officials has provoked either a ballot campaign seeking to repeal the policy or a lawsuit seeking to invalidate it. In nine of these jurisdictions, this countermobilization has been successful.Footnote 10 When local elected officials around the country began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples in spring 2004, SSM opponents responded with lawsuits in San Francisco and in New Paltz, New York, each of which was successful in halting the local efforts.Footnote 11 State lawmakers that have expanded partnership rights have often sparked similar reactions. Hawaii's Reciprocal Beneficiaries Act, Vermont's Civil Unions Act, and California's series of domestic partnership laws have each provoked legal challenges as well as electoral backlashes, and when the Oregon legislature enacted both domestic partnership and antidiscrimination statutes in 2007, opponents responded with petition drives against both statutes and, once the state ruled they had collected insufficient signatures, a federal constitutional challenge to the state's signature verification process.Footnote 12

In short, all victories by LGBT rights advocates have sparked legal and political countermobilization, regardless of whether the victories occurred through legislative, executive, or judicial channels. Each such victory has been a defeat for opponents of LGBT rights, and here, as in the abortion context, “defeats in the legislature, just as surely as defeats in the courts, are likely to generate opposition when issues remain contested” (Reference LemieuxLemieux 2004:244). In this light, the strategy of avoiding political backlash by steering clear of the courts seems unlikely to work.

How Weak Is the Weakest Branch?