Introduction

By recognizing multiple forms of governance within their borders, do states risk undermining national unity and rendering themselves weak and ineffective? States around the world recognize collective self-governance rights for indigenous and tribal communities, defining distinct subnational identity groups and devolving governing powers to nonstate authorities. A recent study found that nearly half of UN member states recognized indigenous governance in their constitutions (Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Haer, Bayer, Behr and Neupert-Wentz2018), while dozens more have done so through statutory provisions (Chartock Reference Chartock2013; Cuskelly Reference Cuskelly2011; Yashar Reference Yashar2005).Footnote 1 These developments find support in international law and are lauded by many as progressive advances in human rights, the preservation of cultural heritage, and environmental protection.Footnote 2 But they also raise important questions for nation-building and state consolidation.

Scholars have long considered a unified national identity and system of government to be prerequisites for the development of effective modern states (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Weber Reference Weber1976). A large body of literature associates the existence of strong subnational identities and nonstate authorities with a range of ills, including state weakness (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Chaves, Osafo-Kwaako and Robinson2014; Herbst Reference Herbst2000; Migdal Reference Migdal1988; Tilly Reference Tilly1992), poor public goods provision (Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Reference Alesina, Baqir and Easterly1999; Miguel Reference Miguel2004; Miguel and Gugerty Reference Miguel and Gugerty2005), and conflict (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Lieberman and Singh Reference Lieberman and Singh2017; Sambanis Reference Sambanis2001). To the extent that recognizing indigenous communities’ collective self-governance rights reinforces these divisions, this work implies such policies will have negative consequences for states.

To date, few studies have directly investigated how collective recognition affects state-building in practice. Yet understanding the influence of these increasingly ubiquitous policies has important implications for understanding the relationship between nationalism and state-building. If policies granting collective self-determination rights to subnational communities indeed weaken national identity and undermine state authority, we require an explanation for states’ adoption of apparently self-undermining policies. If they do not, this suggests a need to revisit foundational theories linking societal heterogeneity to state weakness.

In this paper, I leverage spatial and temporal variation in the granting of communal land titles to indigenous communities in the Philippines to investigate the effects of recognizing collective self-governance rights on communities’ identities and engagement with the state. The Philippines is considered a regional and global leader in the recognition of indigenous rights (Asian Development Bank 2002; Inguanzo Reference Inguanzo2014; Jefremovas and Perez Reference Jefremovas, Perez, Eisenberg and Kymlicka2011), making it an important case and one that provides a relatively fair test of collective recognition as envisioned in international law. Similar to policies adopted by states in the Americas, Australasia, and elsewhere in Asia, the Philippines’ Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) establishes collective property rights to ancestral lands and recognizes the rights of indigenous governing institutions to allocate land and administer justice according to customary law.

In short, I do not find evidence that collective recognition of indigenous communities contributes to state weakness; if anything, my results suggest the opposite. Using a difference-in-differences approach, I find that recognition in the form of communal land titling leads to greater indigenous self-identification on the census. However, I also find that it leads to greater compliance with the state, measured primarily using the registration of births at the community level. I probe mechanisms using evidence from a survey experiment conducted as part of an original face-to-face survey of indigenous communities in three Philippine provinces. I find that priming respondents with information about the government’s collective recognition policy increased reported identification with the nation, relative to one’s tribe and other individual attributes. This finding suggests that collective recognition may encourage compliance with the state in part by fostering legitimating beliefs and creating a sense of belonging within the broader national community, even as it reinforces a subnational indigenous identity.

These findings challenge at least two important theoretical claims in the literatures on state-building and nationalism. First, they call into question the idea that the existence of multiple sources of authority within the same territory undermines state strength (Migdal Reference Migdal1988). In doing so, they support more recent work emphasizing complementarities between traditional and state governance (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2015; Englebert Reference Englebert2002; Logan Reference Logan2013; Van der Windt et al. Reference Van der Windt, Humphreys, Medina, Timmons and Voors2018) and documenting mechanisms through which diversity may encourage the development of state capacity (Charnysh Reference Charnysh2019). Second, they stand in contrast to an important premise of much of the ethnic politics literature: that identification with subnational groupings necessarily comes at the expense of national identity (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Collier Reference Collier2010; Depetris-Chauvin and Durante Reference Depetris-Chauvin and Durante2017; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2018; Miguel Reference Miguel2004). Although these findings do not directly address state motivations, they suggest that collective recognition has the potential to extend the state’s reach into areas where its authority is contested. As such, it may provide an alternative strategy for consolidating state authority in diverse societies.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. First, I introduce my inquiry by discussing the policy debate surrounding indigenous recognition and its relation to the state-building literature. Second, I discuss the history and implementation of indigenous recognition in the Philippines. Third, I describe the observational data and research design. Fourth, I present results from the observational analysis, including robustness checks. Fifth, I discuss behavioral implications of different interpretations of these results and present the survey experiment design and findings. I then consider additional alternative explanations and conclude with a discussion of broader implications and areas for future research.

Indigenous Recognition, National Identity, and the State

In his account of the development of the international legal regime surrounding indigenous rights, Rodríguez-Piñero (Reference Rodríguez-Piñero2006) writes that “international law first defined indigenous peoples to see them disappear” (172). During the period of global decolonization following the Second World War, the term “indigenous” came to to describe populations that had not yet integrated into the national communities of newly independent former colonies (Rodríguez-Piñero Reference Rodríguez-Piñero2006, 164, emphasis mine).Footnote 3 Assimilating these populations to create homogenous societies with “no legal space between the state and the individual,” was seen at the time as a precondition for achieving modernization and development (Rodríguez-Piñero Reference Rodríguez-Piñero2006, 6). Owing to efforts of indigenous rights advocates and an evolution in the concept of human rights in international law, indigenous peoples’ collective self-determination rights have become widely accepted on the international stage (Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot2016). Yet at least through the 1970s, the self-determination of independent nation-states was considered directly at odds with the self-determination of subnational communities of any kind (Jung Reference Jung2008; Rodríguez-Piñero Reference Rodríguez-Piñero2006).

Similar concerns permeate the political science literature on state-building, where institutional and cultural homogenization are frequently characterized as precursors to effective state consolidation (Linz Reference Linz1993; Weber Reference Weber1976; Zolberg Reference Zolberg1967). This literature suggests at least three distinct mechanisms through which the recognition of collective self-determination rights may undermine state authority. First, ceding additional powers to nonstate authorities may increase the population’s reliance on these authorities and empower them to resist state priorities (Levi Reference Levi1989; Migdal Reference Migdal1988; Soifer Reference Soifer2016). Second, these policies may calcify ethnic divisions and/or strengthen subnational identities (Chandra Reference Chandra2006), weakening solidarity with the national community (Ekeh Reference Ekeh1975; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2018; Lemarchand Reference Lemarchand1972; Mill Reference Mill1861) and fueling ethnic conflict (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985; Lieberman and Singh Reference Lieberman and Singh2017). Third, recognition may undermine the quality of democratic representation by empowering nonstate authorities as patrons and vote brokers (Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014; de Kadt and Larreguy Reference de Kadt and Larreguy2018; Koter Reference Koter2013; Lemarchand Reference Lemarchand1972; Mershon Reference Mershon2015; Ntsebeza Reference Ntsebeza2005) or complicating accountability for governance outcomes (Harding Reference Harding2015; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2003; Lieberman Reference Lieberman2011), resulting in performance deficits that compromise state legitimacy (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009).

However, in addition to a paucity of empirical evidence on the effects of collective recognition, there are important reasons to question predictions derived from this literature. I highlight two here. The first is empirical, relating to challenges in inferring the causal direction in the relationship between societal fragmentation and state strength. If it is the case, as Scott (Reference Scott1998), Migdal (Reference Migdal1988), and others have argued, that states generally seek to establish monopolies on many forms of social control, it is presumably the least capable states that have failed to do so. In other words, state weakness may be a cause rather than a consequence of states’ failure to centralize authority and homogenize populations within their borders (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2016). With respect to recognition specifically, decisions by states to empower nonstate authorities rather than sidelining them may reflect an unfavorable preexisting balance of power between national and local elites (Boone Reference Boone2003; Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Ziblatt, Van Gorp and Arévalo2011).

The second critique is theoretical and substantive, building on work suggesting that recognition may strengthen rather than undermine state authority. Recent work on the relationship between traditional and state authority argues that they can be complementary and mutually reinforcing rather than competing (Logan Reference Logan2013; Mershon Reference Mershon2020; Van der Windt et al. Reference Van der Windt, Humphreys, Medina, Timmons and Voors2018). Strengthening preexisting indigenous leadership structures and rationalizing their relationship to state authorities may facilitate connections between the central state and peripheral populations (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2015) and, in doing so, increase the state’s legitimacy (Englebert Reference Englebert2002). Relatedly—though with different normative implications—collective recognition may strengthen the state’s coercive capacity by simultaneously increasing traditional authorities’ loyalty to the state and their power to exact compliance with state priorities (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2011; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996). The process of recognition may also increase state control by making indigenous communities more “legible” (Scott Reference Scott1998) and redefining indigenous authority structures on terms controlled by the state (Kyed and Buur Reference Kyed, Buur, Buur and Kyed2007; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2012; Simpson Reference Simpson2017).

Another relevant body of work concerns the relationship between subnational ethnic identity and identification with the nation. While these are often assumed to be at odds, prominent theories of institutional design argue that group-based representation can increase systemic legitimacy in divided societies, even as it reinforces subnational identities (Elkins and Sides Reference Elkins and Sides2007; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999). Wimmer (Reference Wimmer2018) argues that it is not the existence of diversity but the political exclusion of certain groups that threatens national cohesion. If collective recognition of historically marginalized indigenous groups facilitates political inclusion, it may have the effect of boosting attachments to the nation (Jung Reference Jung2008). Communal land rights in particular, which form an integral part of the international indigenous rights framework, may serve as a means of incorporating peripheral communities into state political institutions (Dell Reference Dell2012).

A dominant perspective in the state-building literature implies that the recognition of indigenous communites’ rights to collective self-determination poses a threat to states, a view shared by many policy makers up to and during the period following widespread global decolonization. Yet even as states have begun to adopt recognition policies, little empirical evidence exists to evaluate its predictions. This paper represents one of the first attempts to evaluate the effects of collective recognition on identity and compliance with the state. In doing so, I build on recent contributions examining the causes and effects of indigenous recognition (Behr Reference Behr2018; Holzinger et al. Reference Holzinger, Haer, Bayer, Behr and Neupert-Wentz2018). However, in contrast to these studies, which rely on cross-sectional, cross-national comparisons, I use subnational variation within a single country case, holding state-level factors constant and attempting to carefully address concerns about the causal direction between recognition and state strength.

Indigenous Recognition in the Philippines

The government of the Philippines defines indigenous peoples (IPs) as “homogenous societies identified by self-ascription and ascription by others, who have continuously lived as organized community on communally bounded and defined territory, and who have, under claims of ownership since time immemorial, occupied, possessed and utilized such territories, sharing common bonds of language, customs, traditions, and other distinct cultural traits, or who have, through resistance to political, social and cultural inroads of colonization, non-indigenous religions and cultures, become historically differentiated from the majority of Filipinos.” The dichotomy between minority IP groups and the majority Christian Filipino population emerged during the Spanish colonial period (Jefremovas and Perez Reference Jefremovas, Perez, Eisenberg and Kymlicka2011). Groups now designated as IPs were distinguished by their refusal to settle in pueblos established by the colonial state, adopt Christianity, and submit to colonial rule (Asian Development Bank 2002; Prill-Brett Reference Prill-Brett2007; Scott Reference Scott2010).

The Spanish and American colonial governments adopted generally assimilationist approaches toward these communities. Spanish colonial-era laws and decrees named the “civilization” of so-called indios or non-Christian tribes as an explicit goal.Footnote 4 The United States, after taking control of the territory from Spain in 1898, established a Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes to govern these “backward” communities until they were sufficiently “advanced in civilization” to live in regularly organized municipalities (Jefremovas and Perez Reference Jefremovas, Perez, Eisenberg and Kymlicka2011). Elements of this policy continued following independence from the United States in 1946. The 1973 constitution gave consideration to the “customs, traditions, beliefs, and interests of national cultural communities,”Footnote 5 but subsequent policies still sought the integration of “national minorities.”Footnote 6 With respect to land rights specifically, the Spanish Regalian Doctrine, which stated that all lands and natural resources in the public domain belonged to the state, remained virtually unchanged from the Spanish colonial period (Leonen Reference Leonen2004; Prill-Brett Reference Prill-Brett1994).

The 1987 constitution represented an important departure from this approach, asserting that the state had a duty to protect the rights of indigenous communities to occupy their ancestral lands and maintain their distinctive cultures, traditions, and institutions. The constitution and subsequent Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997 reflected changing international norms with respect to indigenous peoples, drawing heavily in their language from international conventions such as the Draft UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) and the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of 1989 (ILO Convention 169). These measures, according to some observers, reflected a “paradigm shift” in the government’s treatment of indigenous peoples, “[challenging] the notion that the state had a monopoly on the exercise of law” (Oxfam 2013).

The IPRA recognized unprecedented rights for indigenous communities, particularly regarding the control and ownership of ancestral lands.Footnote 7 The law established a novel tenurial instrument, known as a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT), which guarantees an indigenous community’s rights to land it has owned, occupied, or used since “time immemorial,” prior to the Spanish conquest. These include rights to private but communal ownership of the land, to regulate the entry of migrants into the territory, to develop land and natural resources—including to negotiate the terms of resource exploration within the domain and to share profits from resource extraction—and rights to resolve land disputes and allocate land in accordance with customary law.Footnote 8

Within ancestral domains, customary law is considered to have primacy over the laws of the state. In practice, this means that land allocation and the resolution of disputes within the community are conducted in accordance with customary law. In addition, all public and private projects within Ancestral Domains require free and prior informed consent (FPIC) from the community before proceeding (Oxfam 2013).Footnote 9 Finally, all ancestral domains are exempted from real property taxes, with the exception of large commercial projects.Footnote 10 While the rights detailed in the IPRA apply to all indigenous communities in the Philippines, CADTs—legal instruments recognizing some of the most important among these rights—have been issued unevenly among eligible communities and over time. I leverage this spatial and temporal variation in titling to study the effects of collective recognition at the community level.

Research Design and Data

I use a multimethod research design to study the effects of indigenous recognition in the Philippines context. First, I analyze administrative data, leveraging spatial and temporal variation in the granting of CADTs nationwide. Second, to explore individual-level mechanisms, I present results from an original survey experiment conducted among indigenous respondents in three provinces: Oriental Mindoro, Occidental Mindoro, and Palawan. In this section, I describe the titling process, relevant community-level variation, administrative data sources, and research design. I then present results from this part of the analysis before moving on to discuss the survey.

Variation in Titling

CADTs are granted by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP), a government agency established under the IPRA law. A community seeking a CADT must provide evidence of its claims to have occupied a particular area since time immemorial. Such evidence may include sworn testimony of elders, written accounts of customs and traditions, photographs showing long-term occupation and land improvements, genealogical surveys, and anthropological data. The community must also document their customary laws and designate traditional leaders and Indigenous Peoples Organizations (IPOs) who are authorized to enter into agreements on the community’s behalf. Finally, the NCIP must conduct a professional land survey, funded by the claimants or their representatives.

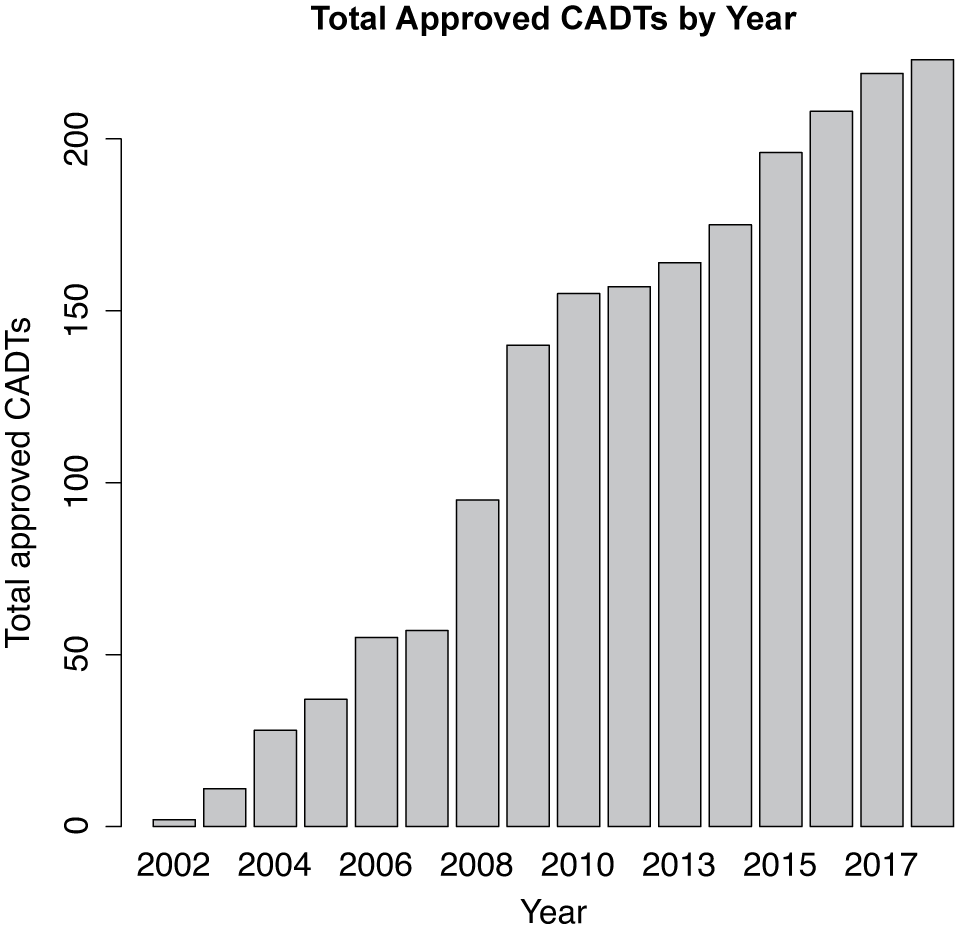

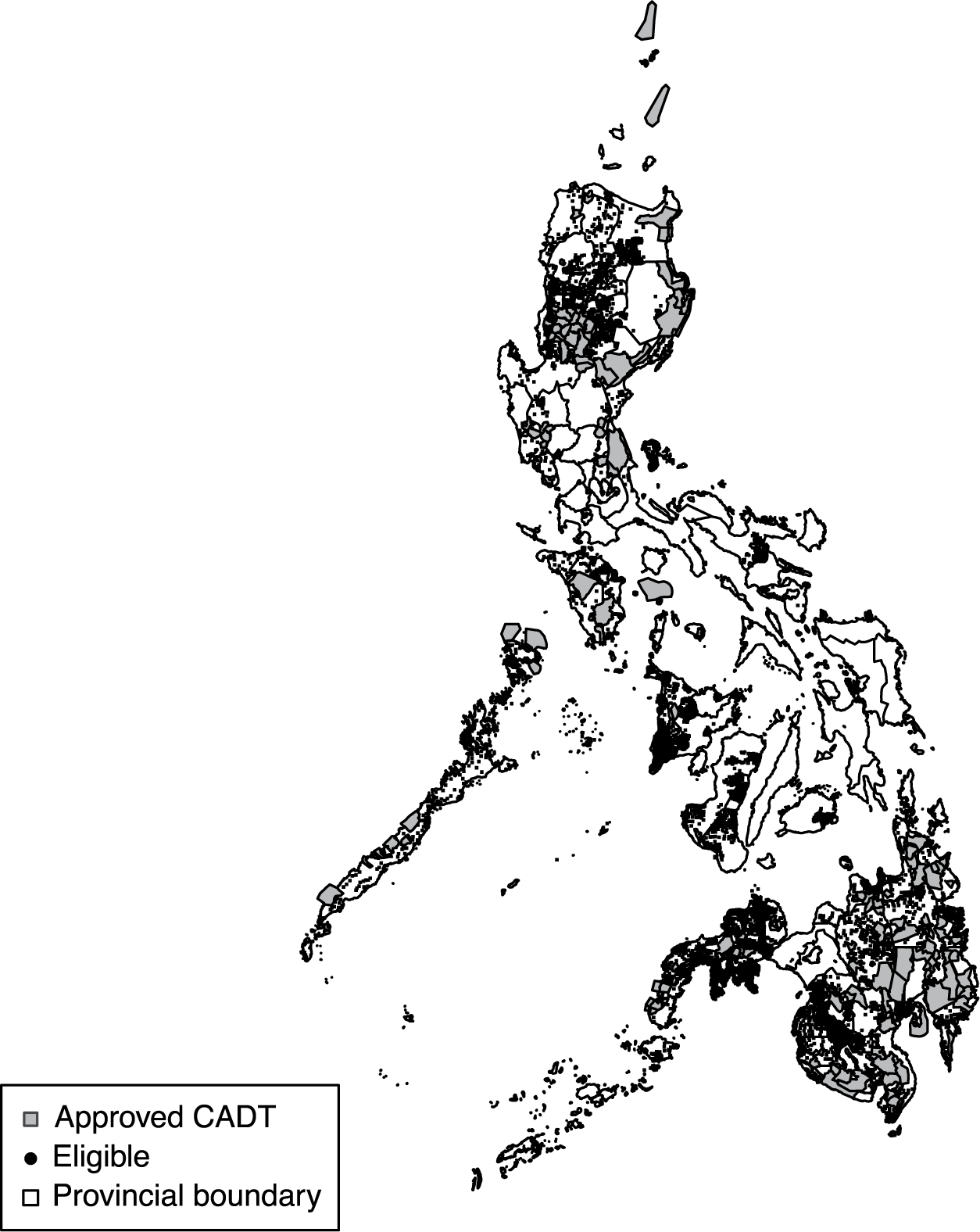

As of March 2018, a total of 223 CADTs had been granted nationwide, covering more than 5.3 million hectares, about 18% of the country’s total land area. In addition, approximately 260 communities had applications under processing.Footnote 11 Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of CADTs approved per year between 2002 and 2018. Figure 2 shows the geographic distribution of approved CADTs and additional communities designated as eligible but not yet titled.

Figure 1. Cumulative Number of Certificates of Ancestral Domain Title (CADTs) Approved by Year, as of March 2018

Note: Data source: National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

Figure 2. Land Area Covered by Approved Certificates of Ancestral Domain Title (CADTS) as of October 2016 and Eligible Areas

Note: Eligible areas are designated using the centroids of barangays listed as part of an untitled ancestral domain. Actual boundaries of eligible areas, which may include portions of individual barangays, are not published until the title is issued. Data source: National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

The boundaries of CADTs and CADT applications do not necessarily correspond to preexisting administrative boundaries. In some cases, one CADT covers portions of multiple barangays, the smallest administrative units in the Philippines. In others, only a portion of a single barangay is covered. The 223 approved CADT applications cover 1,707 unique barangays across 272 municipalities. Areas included in submitted or in-process CADT applications span 4,055 barangays. In addition to these areas, communities in 2,870 barangays where no application has been submitted have been identified as part of eligible ancestral domains by the NCIP.Footnote 12 This makes a total of 8,651 barangays that may be considered part of a “universe” of potentially titleable areas, approximately 21% of all barangays in the Philippines.

Empirical Strategy

The existence of subnational variation in recognition through land titling provides an opportunity to examine the effects of collective recognition of indigenous communities, holding state-level factors constant. Yet land titles are not randomly assigned, creating challenges in inferring a causal relationship from naive cross-sectional comparisons between titled and untitled communities. Communities that already have an affinity with the state may be more likely to apply for land titles, and leaders who are more effective or politically connected may be more effective at obtaining them. As shown in Table A.1 in the appendix, titled and untitled communities within the eligible universe differed in important ways at baseline. In 2000, prior to the issuing of the first title, barangays covered by titles had, on average, a higher proportion of the total population identifying as indigenous and a lower proportion identifying as Catholic, compared with currently untitled communities. By some measures, titled barangays were more integrated at baseline: they had less rugged terrain and were more likely to have an elementary school and a health center. By others, they appeared less so: titled communities were on average farther from the coast and the road network and had lower baseline rates of birth registration.

I address this inferential challenge using a difference-in-differences approach, comparing change over time in titled and untitled communities. This strategy accounts for fixed community-level characteristics that may affect both titling status and outcomes, such as the preexisting strength of indigenous political institutions, historical political connections, and natural resource wealth. It relies on the assumption there is no time-varying confounding—in other words, that titled and untitled communities would have followed parallel trends in the absence of the titling “treatment.” This assumption would be violated if, for example, indigenous communities integrating at faster rates were able to obtain titles earlier. While I cannot rule this out completely, I use a number of strategies to increase or probe the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption.

First, I restrict the sample to communities designated by the NCIP as part of the eligible universe of titleable areas. Second, I implement a preprocessing step that matches communities that received titles prior to the 2010 census to eligible communities that did not, on pretreatment outcomes and a number of pretreatment predictors of titling. Third, I further restrict the eligible subset to communities that were eventually titled as of 2018, leveraging only variation in whether they received the title prior to enumeration of the 2010 census. Table A.2 in the appendix shows pretreatment covariate balance between barangays titled prior to 2010 and each of these subsets (eligible but not titled before 2010, matched controls, and titled after 2010).Footnote 13

Within these subsets, I assume that the vast majority of “untreated” communities had applied for a title prior to 2010.Footnote 14 Anecdotal evidence suggests that the timing of when titles are issued is determined in part by factors unrelated to community characteristics. In interviews with relevant stakeholders, delays in the issuing of titles were frequently attributed to a backlog of applications and lack of capacity on the part of the NCIP. In addition, as described below, I use indirect tests to evaluate the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption and conduct a range of placebo tests and robustness checks.

Outcomes

I estimate the effects of collective recognition through titling on two outcomes theoretically linked to state consolidation: subnational identification (in this case indigenous self-identification) and compliance with the state. As discussed above, strong attachments to subnational identity groupings are frequently associated with state weakness and conflict. If state recognition of subnational groups strengthens subnational identification, we might expect it to exacerbate state-building challenges attributed to ethnic division and other forms of societal diversity. I measure indigenous self-identification using data from the 2000 and 2010 waves of the Philippine Census of Population and Housing and capture the proportion of individuals in a barangay who self-identify with one of the ethnic groups recognized as indigenous by the NCIP.

If it is the case that collective recognition weakens the state, we should expect to find evidence that the state’s ability to project its authority and achieve its goals with respect to affected populations is compromised as a result of this recognition. I operationalize this concept using birth registration as an indicator of compliance with state priorities. Birth registration is an important tool for states to track their populations (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2018). The Philippines has made explicit efforts to increase birth registration rates among its population (Abouzahr Reference Abouzahr2014). Yet birth registration rates have historically been lower among indigenous communities compared with the rest of the population (Philippine Statistics Authority 2017). This disparity is attributed to distrust of the government, resistance to giving birth in government-run health facilities, and difficulty in accessing these facilities. In the Philippines and elsewhere, birth registration is necessary to obtain many other documents required to avail of government programs and citizenship rights (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2018; Scott Reference Scott1998). Efforts to increase birth registration have included registration drives targeting adults as well as parents of newborns (Abouzahr Reference Abouzahr2014). This measure therefore not only captures compliance with an explicit state priority but may also reflect perceived benefits of engagement with the state more broadly.

I define birth registration as the proportion of a barangay’s residents whose births are registered with a city or municipal Civil Registry Office, as reported on the census.Footnote 15 This variable is measured for four census waves: 2000, 2007, 2010, and 2015.Footnote 16 Table A.3 in the appendix shows summary statistics for all barangays included in the main analysis.

Estimation

The primary unit of analysis in this study is the barangay, the lowest level at which outcomes are measured. All administrative data analyses estimate the relationship between a barangay’s titling status in year t and the value of the dependent variable in that year using the following specification:

where Xit represents the titling status of barangay i in year t, Zit represents a vector of time-varying covariates, λt is a year fixed effect, and ci is barangay (unit) fixed effect.

Titling status (Xit) is operationalized in the main analysis by calculating the proportion of a barangay’s land area that fell within a CADT in a given year, using the map published by the NCIP in 2016. As a robustness check, I replicate the analysis using a binary measure based on a separate list of barangays obtained from NCIP in 2018.Footnote 17 In the main analysis, standard errors are clustered at the level of the barangay (Bertrand, Duflo, and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand, Duflo and Mullainathan2004); however, I also employ alternative specifications that account for spatial correlation.Footnote 18 In addition, I estimate all models excluding time-varying covariates Zit, due to potential posttreatment bias induced by the inclusion of endogenous controls.

Results

Indigenous Identity

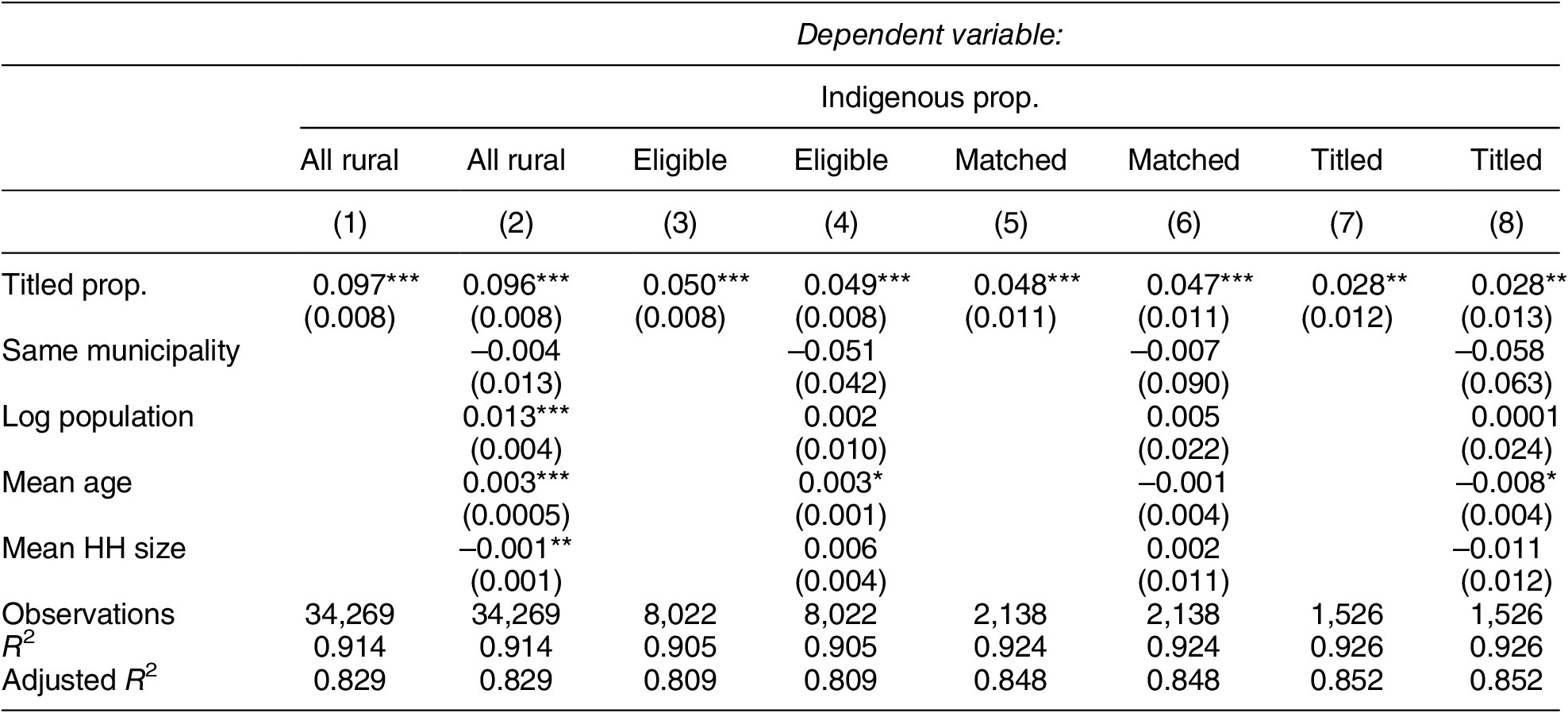

To test for the effects of collective recognition on indigenous identification, I compare change over time in the proportion of barangay residents self-identifying as a member of an indigenous ethnic group in barangays that received a CADT between the 2000 and 2010 census waves and in barangays that did not. Results from this analysis appear in Table 1. Column 1 shows the estimate using all rural barangays. The coefficient is statistically significant and substantively large: full coverage of a barangay’s land area with a CADT between 2000 and 2010 is associated with a nearly 10-percentage-point increase in the proportion of individuals identifying as a member of an indigenous ethnic group.

Table 1. Land Titling (Continuous) and Indigenous Identification

Note: CRSE at barangay level; *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Columns 3, 5, and 7 show estimates from the same analysis using various subsets of the data for which parallel trends are more plausible. In column 3, I estimate the effect of land titling the set of barangays in the eligible “universe” designated by the NCIP. This includes barangays that received a land title at any point between 2000 and 2018, barangays for which CADT applications have been submitted, and barangays not covered by a title or an application that have been identified as eligible by an NCIP regional office. In column 5, I restrict the analysis to a matched subset of these eligible barangays. I use propensity-score matching to match all barangays that were “treated” as of 2010 (using the binary land titling indicator) to eligible barangays untreated during that period on a number of pretreatment covariates. These include pretreatment outcomes; the presence of various public facilities in 2000; pretreatment trends on various demographic characteristics measured in the 1990 census; and geographic characteristics such as land area, terrain ruggedness, soil quality, distance to the 1980 road network, and distance to the coast.Footnote 19 Column 7 restricts the sample of eligible barangays to those that, as of March 2018, were covered by a land title, leveraging only variation in when titles were granted relative to the enumeration of the 2010 census.

The coefficient decreases in magnitude within these latter three subsets compared with the full rural sample, but it remains positive and statistically significant. Coefficients are equivalent to between 0.15 and 0.70 standard deviations in the change in indigenous self-identification between 2000 and 2010 among untitled barangays within each subset.

One immediate concern with the interpretation of these results is that the estimates may reflect changes in barangay-level population composition as opposed to changes in the propensity of individuals to self-identify as indigenous on the census. Once an area is covered by a CADT, indigenous people may decide to move to that area, indigenous people may out-migrate at lower rates, or nonindigenous people may out-migrate at greater rates. As shown in columns 2, 4, 6, and 8 of Table 1, the results remain virtually unchanged when controlling for change in total population and the proportion of individuals in the barangay who have lived in the same municipality for the past five years, both rough proxies for differential in- and out-migration across subsets. I also conduct the same analysis using these controls as dependent variables and do not find consistent effects of land titling in either direction across subsets, suggesting that differential in- or out-migration is unlikely to explain the main findings.Footnote 20

State Compliance

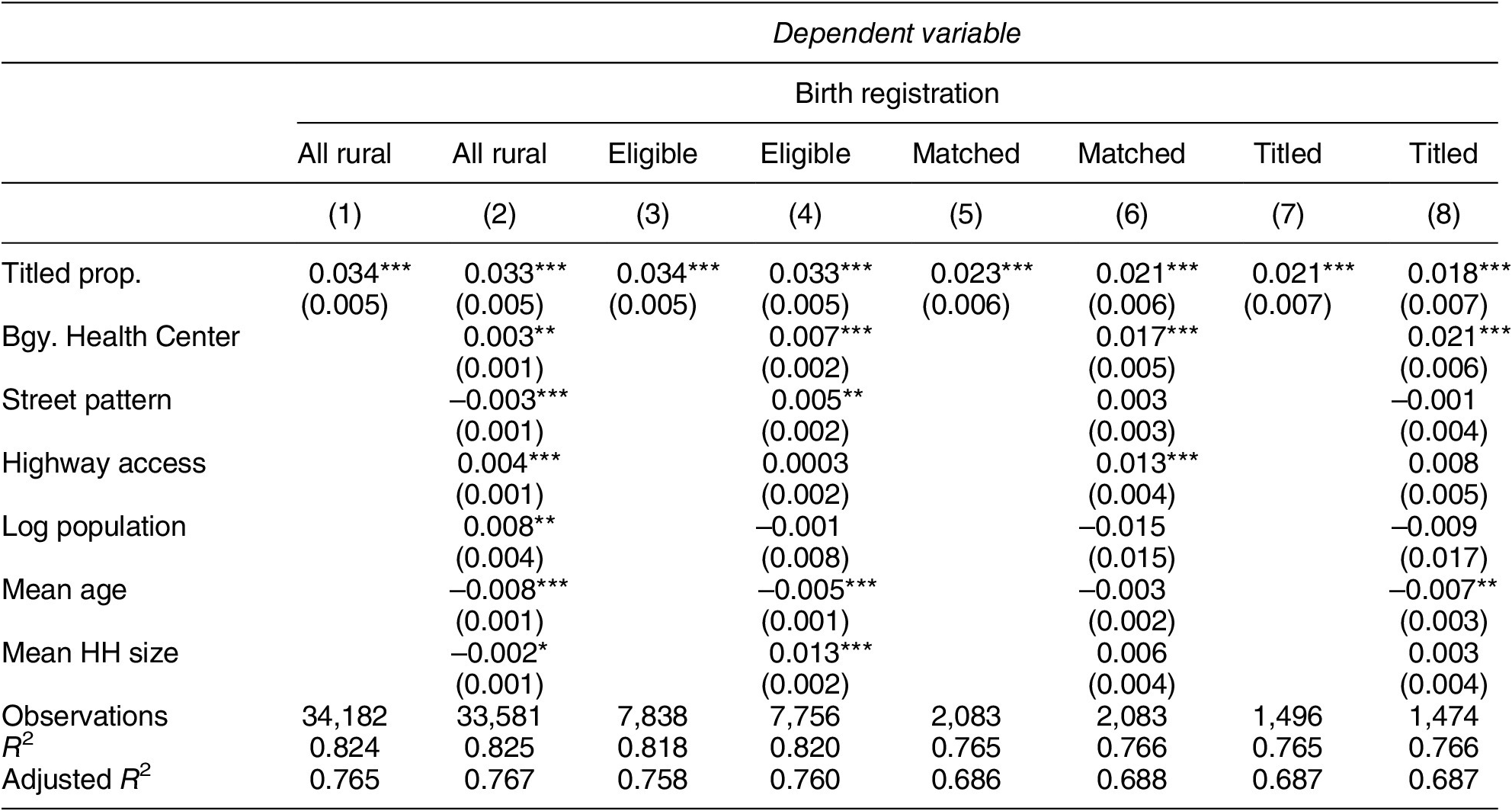

Next I estimate the effects of receiving a CADT on birth registration, an indicator of compliance with the state. Birth registration is measured in four census waves: 2000, 2007, 2010, and 2015. Prominent theories of state-building argue that policies strengthening subnational identities and nonstate authorities can weaken the state’s authority and ability to achieve its policy goals. If this is the case, we would expect collective recognition in the form of titling to lead to a reduction in compliance.

Table 2 shows results for the birth registration outcome using the same subsets: all rural barangays, barangays designated as eligible by the government, eligible barangays matched to barangays titled in 2010 on pretreatment covariates, and all barangays that were eventually titled. The models in columns 2, 4, 6, and 8 control for a number of potential time-varying confounders including change in population, the presence of a health center, and street and highway access. In all models and all subsets, titling leads to a significant positive increase in the proportion of the barangay population whose births are registered, with estimates ranging between 2 and 3 percentage points.

Table 2. Land Titling (Continuous) and Birth Registration

Note: CRSE at barangay level; *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

These results are both statistically and substantively significant, across all specifications. The coefficient estimates in Table 2 represent between 0.13 and 0.22 standard deviations in barangay-level change in birth registration between 2000 and 2010 among untitled barangays and account for between 15% and 24% of the baseline difference in average birth registration rates between majority-indigenous and non-majority-indigenous rural barangays. Footnote 21 To address concerns about reverse causality—specifically that places more compliant or legible at baseline were more likely to obtain land titles—I estimate lagged dependent variable models, predicting birth registration with land titling in the following period. A lagged effect is observed in the model including all rural barangays but not in any of the other three subsets.Footnote 22

Robustness Checks

I conduct a range of additional tests to probe the robustness of these findings and address potential threats to inference. While the difference-in-differences approach accounts for unit-level time-invariant confounding, it does not account for time-varying confounding. This is a particular concern for the identity outcome, which is only measured for two periods. It could be the case, for example, that communities that obtained titles earlier have also been better able to maintain indigenous identity over time due to more effective leadership or greater community cohesion. The estimated effect of titling could also be capturing the effect of the application process rather than the effect of titling itself, and communities that applied earlier may follow divergent trends from those who applied later.

I implement several tests to probe the plausibility of the parallel trends assumption. First, I conduct a bandwidth analysis, repeating the main two-way fixed effects specification from Equation 1 successively restricting the analysis to include subsets of eventually titled barangays that received their titles within shorter windows of time around the 2010 census.Footnote 23 Within a shorter bandwidth, the timing of titling relative to census enumeration is more plausibly exogenous. As shown in Figures A.1 and A.2 in the appendix, the coefficients remain positive and similar in size across a bandwidth range between two and eight years for both outcomes. Second, I implement a quasi-regression discontinuity specification, using the timing of titling relative to the census as the running variable. Results for both outcomes appear in Tables A.4 and A.16 in the appendix and are generally consistent with the main findings. Third, I incorporate data on the date of CADT application filing, within the subset of CADTs for which this information is available.Footnote 24 Within this subset, I estimate first-difference models, regressing change in both outcomes between 2000 and 2010 on titling status in 2010 and controlling for filing year. Results are consistent with the main findings, with point estimates similar to those in the titled subset.Footnote 25 Fourth, I examine change over time in indigenous self-identification between 2000 and 2010 for communities that received titles at different times after 2010. If communities that received titles earlier were on differentially increasing trajectories, we should expect greater pretreatment increases among those that received titles earlier in the post-2010 period compared with those that received titles later. To test this, I compare change in indigenous identification between 2000 and 2010 for communities that received a title between 2011 and 2014 and those that received a title between 2015 and 2018. I find no statistically significant difference in pretreatment trends between these two groups (p = 0.88).

To further investigate potential differences in pretreatment parallel trends, I conduct two additional tests. First, I examine pretreatment trends on various demographic variables available in the 1990 census (unfortunately, neither of the main outcome variables used in the paper was collected in 1990). While some differences exist within the eligible universe, I do not observe differential pretrends in the matched or titled subsets.Footnote 26 Second, I construct a pseudopanel of birth registration by age cohort and compare age cohorts in treated and untreated communities, using data from the 2000 census. As shown in Table A.28 in the appendix, pretreatment cohort trends do not differ substantially between titled barangays and the various reference groups used in the main analysis.

In addition, I estimate first-difference specifications for both main outcomes—indigenous identification and birth registration—including province and region fixed effects.Footnote 27 I also reestimate all main specifications using Conley standard errors that account for both spatial and temporal autocorrelation (Conley Reference Conley1999). This is important given that Ancestral Domains do not correspond directly to barangay boundaries and in some cases cover portions of multiple neighboring barangays. However, the results remain largely unchanged when spatial dependencies are taken into account.

Taken together, these findings present a pattern not anticipated by dominant theories of diversity and state building. On the one hand, they are consistent with predictions from the ethnic politics literature that collective recognition—a form of subgroup classification by the state—can reinforce subnational identities. However, they are inconsistent with the prediction that, in doing so, collective recognition weakens the state by hindering its ability to achieve compliance among the populations concerned. In the next section, I present results from an original survey experiment conducted among indigenous communities in the Philippines that addresses potential mechanisms by exploring the relationship between collective recognition and individual attitudes.

Exploring Mechanisms: Survey Findings

Why might collective recognition increase both attachments to subnational identity and compliance with the state? One possible explanation is that collective recognition increases the state’s legitimacy among affected populations by increasing alignment between state and nonstate authorities (Englebert Reference Englebert2002) and/or redressing past discrimination and creating the possibility of (group-based) representation within the formal political system (Jung Reference Jung2008; Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999). Other explanations are possible, however. For example, collective recognition may represent an elite bargain whereby the state trades the devolution of control to local elites for coerced community compliance with its directives (Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996; Reference Mamdani2012).

While neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, these explanations generate distinct predictions about the effects of collective recognition on individual, nonelite attitudes. A legitimacy-based explanation would suggest that collective recognition increases individual affinity with the state and identification with the broader national community. Yet much of the ethnic politics literature implies an inverse relationship between subnational and national identity. Evidence that collective recognition strengthens indigenous identity at the expense of national identity would weigh against a legitimacy-based explanation, yielding very different implications for understanding its effects on national cohesion. In this section, I present evidence from a experiment embedded in a survey of indigenous respondents in three Philippine provinces, which tests the effects of priming collective recognition on identification with one’s tribe relative to the nation and other identity characteristics.

Survey Data and Priming Experiment

The survey was conducted in partnership with Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), a Philippines-based NGO.Footnote 28 Figure A.7 in the online appendix shows the locations of targeted and surveyed barangays. The sample used in this analysis includes 476 indigenous respondents from 80 barangays in the provinces of Oriental Mindoro, Occidental Mindoro, and Palawan.Footnote 29 Respondents were sampled in communities with and without CADTs. In the final sample, communities in 30 of the 80 barangays were part of a CADT. All interviews were conducted face-to-face by locally recruited enumerators and administered on tablets. Two sitios, or neighborhoods, were randomly selected within each barangay and respondents were selected within each sitio using a random walk procedure.Footnote 30

In the embedded survey experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to receive an informational treatment about the IPRA law or not.Footnote 31 For respondents in the treatment condition, enumerators were instructed to show a physical flyer to respondents and read its contents aloud.Footnote 32 This priming treatment was intended to make the government’s recognition of collective rights for the country’s indigenous communities salient, as a means of capturing the effects of this policy on individual attitudes.Footnote 33

The outcome was measured using a ranking activity, where respondents were asked to rank four types of identity groupings—tribe, religion, gender, and nationality—in order of importance to them as components of their individual identities. Respondents were presented with four show cards representing their tribe, their gender, their nationality, and their religion, placed in a random order assigned to the enumerator on the tablet. Respondents were then asked to rearrange the cards in order of importance to them as parts of their identity.Footnote 34 The quantity of interest in the experiment is the average treatment effect of the prime on the ranking of the tribe attribute, relative to the other three characteristics.

Results

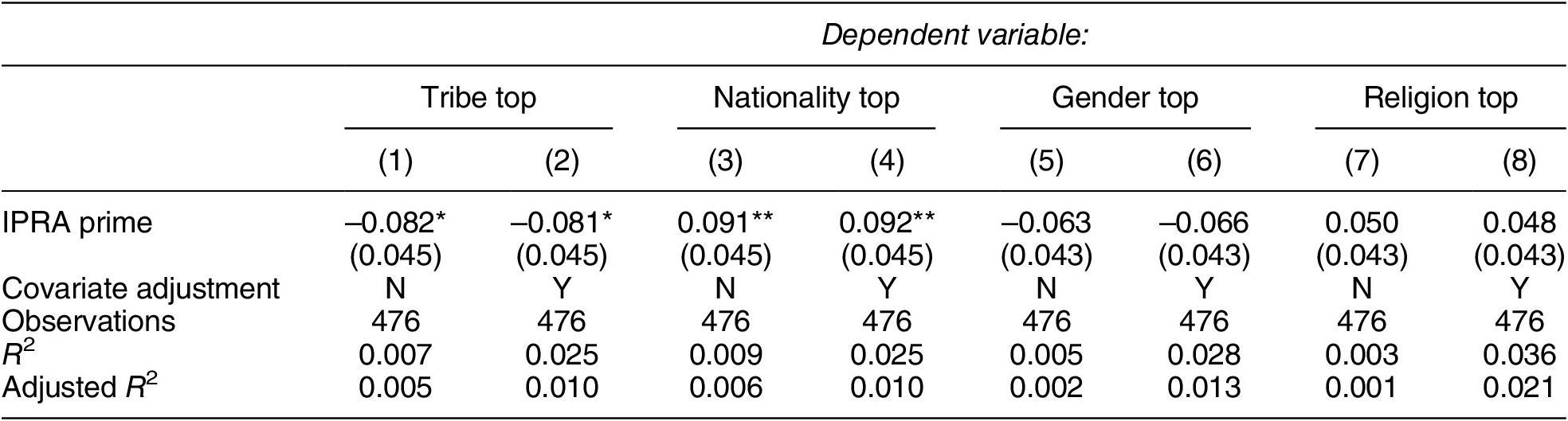

Table 3 shows estimates of the effects of the priming treatment on the ranking of four identity attributes: tribe, nationality, gender, and religion, with and without covariate adjustment.Footnote 35 The coefficients can be interpreted as the effect of the treatment on the probability that a given attribute is ranked in one of the top two positions. As shown in columns 1 and 2, the priming treatment did not lead to an increase in the relative salience of the tribe attribute. If anything, the effect is in the opposite direction. However, the treatment led to a substantively large and statistically significant increase in the salience of the nationality attribute: respondents who were given information about the government’s policy of recognition for indigenous communities were more than 9 percentage points more likely to select nationality as one of their two most important attributes.Footnote 36

Table 3. Prime Treatment and Top Ranking of Identity Attributes

Note: *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

These findings weigh against the idea that increases in indigenous self-identification resulting from the recognition of indigenous communities by the state come the at the expense of identification with the nation. If anything, they suggest the opposite and provide suggestive evidence in favor of a legitimacy-based explanation of the observational findings. As a more direct (exploratory) test of this argument, I estimate the effects of the prime on a battery of questions measuring attitudes toward local government officials.Footnote 37 Figure A.6 in the appendix shows the effects of the prime on a preregistered index of these questions and on each index component. Compared with the control group, respondents primed with information about the IPRA law expressed higher affinity toward local government, with a coefficient significant at the 10% level (p = 0.053). They were not, however, more likely to believe that the government had conducted the survey, weighing against social desirability bias as an alternative explanation. In addition, I estimate heterogeneous effects by actual titling status. Receiving information about the government’s policy recognizing collective rights is different from having those rights recognized in practice. Individuals whose communities have received titles can relate the priming treatment to their actual experience. By contrast, for individuals in communities without titles, this experience is hypothetical and expectations about the priming effect are not as clear.Footnote 38 For some in untitled areas, knowledge of the government’s general policy of collective recognition may have effects in the same direction as the actual experience of titling. For others, being primed may instead remind them that they do not yet have a title.

Results from this analysis appear in Table A.33 in the appendix. While the coefficient on the interaction between the priming treatment and titling status is not statistically significant, the point estimate for the effect of the priming treatment on national identity is nearly twice as large for respondents in the titled communities than for those in untitled communities. This finding supports the idea that the survey experiment, while removed from the real-world policy of collective recognition, conveys some information about the latter’s effects on individual attitudes.

The survey experimental findings offer suggestive evidence that collective recognition of historically marginalized indigenous communities can increase state legitimacy and attachments to the broader national community. Rather than increasing attachments to tribal identity at the expense of national identity, providing information about the government’s collective recognition policy increased the relative salience of respondents’ national identity and improved attitudes toward local government. This evidence does not directly address the mechanisms behind the observational findings, nor does it rule out an elite bargain or other alternative explanations. However, consistent with a legitimacy-based interpretation, it suggests that collective recognition of subnational groups has the potential to increase attachments to the broader national community and affinity with state institutions among nonelite members of the recognized group.

Additional Alternative Explanations

In this final section, I consider several additional alternative explanations for the pattern of results from the observational analysis. The first is that the effects of collective titling on indigenous identity reflect purely instrumental behavior. Individuals in these communities—regardless of whether they would qualify as indigenous by some “objective” standard—may be more likely to falsely identify as such because they expect it will lead to material benefits such as land ownership within the ancestral domain or access to benefits from negotiated settlements between outside actors (i.e., private companies) and the tribe. On its face, this is unlikely given that indigenous status for the purposes of allocating these benefits would not be determined by a response to the census but by the tribal leadership in a particular community. If this were the case, however, we might expect differentially greater positive effects of titling in areas with more valuable land. I test this proposition by interacting the titling variable with two proxies for land value: the presence of mineral deposits and a soil quality index. As shown in Table A.27 in the appendix, we do not see evidence of differentially greater increases in indigenous self-identification in titled communities with more valuable land. A related possibility is that receiving a title informs indigenous individuals about the possibility of self-identifying as indigenous. This too seems unlikely given the high political salience of this identity category. Furthermore, if titling does provide this information, we would expect it to apply to communities going through the titling process even prior to receiving a formal title.

A second potential alternative interpretation of the indigenous identity findings is that they represent changes in the behavior of census enumerators rather than changes in the behavior of individuals responding to the census. Ethnicity is always reported by the respondent, not inferred by the enumerator (National Statistics Office 2010). However, enumerators are instructed to list example ethnic groups and therefore have some ability to “suggest” possible responses.Footnote 39 In order for this to drive the results, the enumerators must be systematically more likely to name indigenous ethnic groups in titled areas than eligible indigenous communities that are untitled, including those undergoing the titling process at the time of census enumeration. This cannot be ruled out directly with the data at hand. To understand whether it is plausible, I interviewed representatives of the Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) regarding procedures for census enumeration in indigenous communities. The PSA does coordinate with the NCIP when working in indigenous areas, largely for access reasons. When the NCIP is involved, indigenous identity may be more salient to census enumerators. Yet PSA representatives confirmed they had no knowledge of which indigenous communities had been granted CADTs.Footnote 40 Areas identified by the NCIP as including indigenous communities for this purpose are likely the same as the NCIP-designated “eligible universe” used in the analysis in this paper.

Turning to the birth registration results, I consider the possibility that these findings do not reflect increased compliance or voluntary engagement but are instead a mechanical result of greater “supply” of the state in titled communities. Birth registration is both an expressed priority of the state and a prerequisite for access to many government services. If titling directly results in greater state presence, for example due to a post-CADT push to provide public services, this, rather than greater compliance on the part of communities with birth registration efforts, may explain the differentially greater increases in birth registration observed in titled communities. While the IPRA guarantees the rights of indigenous communities to basic services, this guarantee is not contingent on the issuance of a formal land title, nor does titling guarantee access to specific services.Footnote 41 Still, formal land rights may improve the community’s ability to bargain with the government and private actors, potentially resulting in greater public goods provision.

To further understand the relationship between titling, state investment, and birth registration, I estimate the effects of titling on the presence of various barangay-level facilities.Footnote 42 I find evidence in some subsets of the data that titling is associated with an increase in the presence of barangay health centers and highway access roads.Footnote 43 However, the effects of titling on birth registration hold when restricting the analysis to eligible barangays that were fully serviced in prior periods (i.e., that had a highway access road and a barangay health center in both 2000 and 2007), suggesting that these findings cannot be fully explained by increases in public goods provision.Footnote 44 In addition, I do not find evidence that increases in birth registration are driven by new births, weighing against the possibility that increases in birth registration result directly from mothers giving birth in newly available government health facilities.Footnote 45 In summary, there is some evidence that titling precipitates greater access to state services. Public goods provision (or anticipation thereof) may be a mechanism through which collective recognition facilitates the engagement of indigenous communities with the state system. However, I do not find evidence that observed increases in birth registration are a mechanical result of state presence directly resulting from land titling.

Another question regarding the birth registration results is to what extent they represent meaningful gains in state capacity. The government has identified increasing birth registration among historically marginalized populations as a specific goal. While the results suggest that providing collective land rights increases compliance with this particular initiative, this may not translate to gains in other areas. To better understand the implications for state capacity more broadly, I estimate the effects of titling on two alternative outcomes. The first, legibility, is a measure of census data quality proposed by Lee and Zhang (Reference Lee and Zhang2016) as a measure of “the breadth and depth of the state’s knowledge about its citizens and their activities.” Specifically, it measures the accuracy of age-reporting data and the extent of “heaping” around ages ending in 0 and 5. This measure is conceptually similar to birth registration in that it captures information about the state’s ability to gather information. However, Lee and Zhang (Reference Lee and Zhang2016) validate it against other measures of state capabilities such as tax contributions.Footnote 46 As shown in the appendix, I find consistent evidence that titling leads to significant decreases in age heaping, suggesting that titling may increase state capacity in indigenous areas more broadly.Footnote 47

The second alternative outcome measures the influence of the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines. The NPA has been active since 1969 and has a presence in remote rural areas throughout the country. It has been accused of recruiting from indigenous communities.Footnote 48 If titling increases loyalty to the state, it may hinder insurgent recruitment or increase cooperation with counter-insurgency efforts. To investigate this, I use barangay-level data from military intelligence reports produced by the Armed Forces of the Philippines, available annually from 2011 to 2014 (Rubin Reference Rubin2020). As shown in Table A.30 in the appendix, I do not find evidence that titling leads to a reduction in NPA influence. Given data limitations, these results should be interpreted with caution.Footnote 49 However, they suggest that increased state compliance resulting from the granting of territorial autonomy may not necessarily extend to short-term increases in cooperation with the military.

Discussion

The findings in this paper weigh against predictions derived from an important strand of the state-building literature regarding the effects of collective recognition on state authority, predictions which to date have been largely untested. They are inconsistent with the idea that the devolution of power to nonstate authorities and recognition of subnational identities threatens the state’s ability to implement its chosen policies. Ruling indirectly through existing authorities has long been used as a method of projecting power across territory (Acemoglu, Reed, and Robinson Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014; Baldwin Reference Baldwin2011; Mamdani Reference Mamdani1996; Weber Reference Weber1978; Young Reference Young1997). However, this strategy, while politically expedient, is thought to breed state weakness over the long term (Hutchcroft Reference Hutchcroft2000; Soifer Reference Soifer2016). Instead, my findings suggest that granting collective rights may provide a successful strategy for consolidating state authority, particularly for states that lack the capacity or political will to dislodge existing governing structures and forge national identities from scratch.Footnote 50

These findings also challenge the assumed inverse relationship between subnational identity and identification with a broader national identity, or at the very least raise questions about the types of identity groups to which it applies. This assumption may be more appropriate in contexts where national politics is seen as a zero-sum competition between large regionally based ethnic groups or where there is a credible threat of secession. It may be less appropriate for smaller, more geographically dispersed groups defined by their historical marginalization from the state (Anderson Reference Anderson and Duncan1987; Jung Reference Jung2008). Instead, recognition of these particular types of identities may constitute an expansion of who is included in the overarching national identity rather than a fragmentation of an otherwise potentially cohesive nation. The single country nature also limits the applicability to indigenous recognition more broadly. The Philippines’ indigenous recognition policy is one of the most robust in the world. In countries where policies are less robust, or where rights recognized on paper are not respected in practice, we might not observe the same effects. Future research may broaden the inquiry to other types of group identities or examine indigenous recognition in other contexts.

This study has other important limitations that suggest additional directions for future research. For example, these findings only address the effects of recognition in the short-to-medium term. If recognition raises communities’ expectations beyond what the state can reasonably deliver, these effects may not endure. Support for the state gained through recognition does not appear to be purely driven by material exchange or expectations; however, the extent to which this support is contingent or represents a “reservoir” upon which the state can draw is not immediately apparent (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Tyler Reference Tyler2006).

In addition, this study focuses on the effects of collective recognition on attitudes and behaviors among indigenous communities eligible to receive this recognition. It does not directly address the effects on surrounding communities or intergroup dynamics. If recognition increases claim-making on the state among indigenous communities or leads to greater allocation of resources to these communities at the expense of nonindigenous communities, this could lead to intercommunal conflict. However, it is not clear a priori whether this would ultimately strengthen or weaken the state’s control (Charnysh Reference Charnysh2019). Future research on this topic could include collecting data on the attitudes of surrounding populations and incorporating data on intercommunal conflict specifically.

Conclusion

Accounts of state formation in Europe, most notably Tilly (Reference Tilly1992), popularized the idea of state-building as an act of creative destruction: only through the elimination of competing identities and authorities can a truly effective nation-state emerge. This idea has proven influential in the broader political science literature on state-building and in policy discourse (Linz Reference Linz1993; Neuberger Reference Neuberger1976; Scott Reference Scott1998). In the period following widespread global decolonization, it motivated calls for newly independent states to assimilate indigenous populations as part of an effort to establish a single national identity and system of government.

In recent decades, however, many states have adopted policies recognizing collective self-determination rights for these same communities. This study is one of the first to systematically evaluate whether these policies have the negative consequences for states that these foundational theories imply. Leveraging subnational variation in recognition in the Philippines, I find evidence that collective recognition increases identification with indigenous ethnic groups. At first glance, this may be interpreted in support of the idea that recognition weakens the state by strengthening nonmajoritarian identities. Yet I also find that collective recognition leads to greater engagement with formal state institutions, using birth registration as a measure. Exploratory analyses from a survey experiment support the idea that collective recognition may also encourage greater affinity with the broader nation and more positive attitudes toward the state among historically marginalized indigenous communities. While this mechanism may in part explain the observational findings, birth registration should not be considered a proxy for affinity or legitimacy but instead a direct behavioral measure of engagement with the state.

In this case, collective recognition appears to increase the reach of the state rather than weaken it. Finding evidence against important predictions within the state-building literature, this study suggests a need to revisit the conditions under which they apply. Assimilation may not be a viable strategy for postcolonial states facing fundamentally different background conditions and constraints. When state boundaries are fixed and sovereignty protected by the international system (Centeno Reference Centeno2003; Chowdhury Reference Chowdhury2018; Herbst Reference Herbst2000), theories about the relationship between group representation and legitimacy may prove more applicable than theories about war-making and state-making (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999). These findings also challenge the perception of traditional or nonstate institutions as impediments to development and state consolidation and support recent studies suggesting that these institutions can instead facilitate these processes (Baldwin Reference Baldwin2015; Van der Windt et al. Reference Van der Windt, Humphreys, Medina, Timmons and Voors2018). I build on this work by exploring how the de jure relationship between state and nonstate institutions contributes to the process of consolidating de facto state control.

Finally, and somewhat counterintuitively, these findings suggest that collective recognition may have effects opposite its stated objectives. While policies of collective recognition are often rhetorically motivated by the goals of self-determination and the preservation of distinctive cultures and institutions, these findings suggest they may ultimately have the opposite effect if they encourage greater engagement with formal or mainstream politics (Anderson Reference Anderson and Duncan1987; Corntassel and Witmer Reference Corntassel and Witmer2008) and/or the adaptation of preexisting institutions to conform to state institutions (Wilkins and Lightfoot Reference Wilkins and Lightfoot2008). This is consistent with critiques that recognition has often been used to increase state control (Mamdani Reference Mamdani2012; Simpson Reference Simpson2017) and that recognition policies are only adopted when they serve the state’s objectives (Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot2016).

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001039.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the APSR Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/VW1GDD.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Rich Apollo Mamhot, Vincent Ramos, and Karl Rubio for excellent research assistance and input and to Rona Ann Caritos and the staff of Legal Network for Truthful Elections for facilitating survey data collection. I also thank the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples for their time, insights, and for sharing data on land titling, and the Philippine Statistics Authority for providing census data. I thank Lily Tsai, Evan Lieberman, Roger Petersen, Danny Hidalgo, Andreas Wimmer, Macartan Humphreys, Ariel White, Tugba Bozcaga, Ozgur Bozcaga, Paige Bollen, Andrew Miller, Benjamin Morse, Gabriel Nahmias, Blair Read, Tesalia Rizzo, Leah Rosenzweig, Guillermo Toral, Minh Trinh, Mohamed Saleh, participants at MPSA, APSA, the IAST/TSE Conference in Political Science and Political Economy, the UCLA Comparative Politics Workshop, and the WZB IPI Brown Bag, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper. All errors are my own.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the MIT GOV/LAB Dissertation Grant.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Certificate numbers are provided in the appendix. The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subjects Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.