LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• recognise the impact that healthcare staff's work has on them and their patients, and how stress may originate

• describe contemporary conceptual approaches to understanding the psychosocial experiences of healthcare staff and the components of good psychosocial care to mitigate their needs

• understand how lessons from research and experience might be used to improve employers' evidence-informed capabilities for caring for their staff.

Providing compassionate care for another human being in distress or illness is emotionally draining and physically demanding for everyone. This is not commonly acknowledged. Thus, caring for people can be satisfying but also harmful.

This article focuses on the experiences and needs of the staff of healthcare services as professional carers in order to identify matters that are important influences on what should be included in a workforce strategy to improve care of staff and, thereby, also improve the quality of patient care. It builds on our published work on improving care for staff of healthcare services (Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Sellwood and Wapling2016a, Reference Williams, Kemp, Neal, Bhugra, Bell and Burns2016b; Aitken Reference Aitken, Drury, Williams, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019; Neal Reference Neal, Williams, Kemp, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019). The British Medical Association's (BMA's) opinion is that ‘Securing the health and wellbeing of [healthcare staff] is crucial in order to ensure that the service is able to deliver the best care for patients’ (British Medical Association 2019: p. 3).

The current circumstances in the UK

Using data from the National Health Service (NHS) national staff survey of 2017, NHS Employers reports that over 38% of staff in the NHS in England suffered from work-related stress (NHS Employers 2018). The highest levels of sickness absence were in ambulance services, followed by mental health and intellectual disability (known as learning disability in the NHS) services. Unfortunately, high-quality evidence on the morale of the mental health workforce in the UK and the impact their work has on them is lacking and fragmented (Johnson Reference Johnson, Osborn and Araya2012). But the data available demonstrate that the emotional impact is significant and affects staff in all hospital and community services.

The General Medical Council (GMC) reports that the NHS in the UK ‘is now at a critical juncture’ (General Medical Council 2018: p. 24). It describes the current situation in the UK as not being sustainable and calls for a comprehensive workforce strategy. It reports, ‘intelligence from frontline engagement with doctors has already been picking up multiple signs of a profession under pressure. Doctors feel less supported […] working in a system under such intense pressure’ (p. 11).

Psychiatry and mental health organisations have been under long-term pressure. Compared with other medical disciplines, recruitment into psychiatry is often poorly regarded and this is a global phenomenon (Brown Reference Brown and Ryland2019). There has been an increase in the number of consultant psychiatrists in the UK since 2000, but, despite recruitment campaigns by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the percentage of medical graduates choosing psychiatry has remained steady, at 4–5%, over the past 35 years (Bhugra Reference Bhugra2013). Aarons & Sawitzky (Reference Aarons and Sawitzky2006) write that ‘Staff turnover in mental health service organizations is an ongoing problem with implications for staff morale, productivity, organizational effectiveness, and implementation of innovation’. They found that work culture influences work attitudes, which significantly predicted 1-year staff turnover rates.

Additionally, there have been many reports in the UK into failures in professional care systems. They include, for example, the Winterbourne View Report (Department of Health 2012), the Francis Report (Reference Francis2013), the Andrews Report (Andrews Reference Andrews and Butler2014) and the Morecambe Bay Report (Kirkup Reference Kirkup2015). Each identifies a number of factors that have contributed to system failures. But, too often, the response to mistakes in healthcare is to ascribe blame without acknowledging the impact of diminishing resources against rising expectations. These factors create the conditions in which staff experience stress.

The Stevenson/Farmer Review (Stevenson Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017) of mental health and employers concerns organisations of all types. However, its findings are particularly relevant to staff of organisations that deliver care for other people as their main function.

Figure 1, reproduced from the review report, frames three challenges:

• assisting employees to thrive at work

• supporting staff who are struggling

• enabling people who are ill to recover and return to work.

FIG 1 Three phases people experience in work (Stevenson Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017: p. 16). (© Crown copyright 2017: reproduced under the Open Government Licence v3.0.)

In 2019, the BMA published the findings of its large-scale survey into doctors’ and medical students’ mental health (British Medical Association 2019).

Using these reports and the research literature, this article explores the origins of stress at work within healthcare organisations, identifies core concepts and provides an evidence-informed framework for intervening in response to these challenges.

Stress arising from working in healthcare services

Primary and secondary stressors

Figure 2 is an overview of the sources of stress that healthcare staff experience; they fall into three broad groups:

• the nature of the work done

• the culture in which staff work and the ways in which employers govern, lead and manage services

• sources that relate to practitioners' professional training and development, their personal circumstances and their relationships outside work.

FIG 2 The origins of stress and recovery in delivering healthcare (© R. Williams & V. Kemp 2019. All rights reserved).

The boxes in the second and third rows in Fig. 2 illustrate the sources of stress. Each of these functions may help or stress staff, depending on their application and the sensitivity of employers' and regulators' processes to the needs of staff. They may be divided into primary and secondary stressors. Primary stressors, on the left side of the figure, are the sources of stress, worry and anxiety that stem directly from the tasks and events that the staff of healthcare services face at work. They may reflect single events but, more often, an accumulation of pressure over time.

By contrast, secondary stressors are circumstances, events or policies that are indirectly related to tasks and emotions that face staff but concern the conditions in which they work and live (Lock Reference Lock, Rubin and Murray2012). They also include decisions that staff believe are morally and/or professionally unfair, as notions of organisational justice can markedly influence their motivation and well-being (Latham Reference Latham and Pinder2005). It is usual for secondary stressors to last longer than the challenges from particularly stressful tasks at work (Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Sellwood and Wapling2016a).

Many of the activities in Fig. 2 may be experienced by staff as positive or negative, depending on how they are implemented. Doctors, for example, have reported to us on the great satisfaction they gain from having the time and resources to treat patients to the best of their abilities, but also of the frustration and moral dilemmas they experience when their working circumstances limit their ability to do so. Another example is that of appraisal: it is intended to enable consultants to develop professionally and to achieve greater satisfaction with the quality of their work with patients. Our experience is that this may be the case for most of them, but some face appraisal with apprehension if they see it as other than intended to support their learning and development. A key point is that matters pertaining to clinical governance, including consultant appraisal and the annual reviews of competency progression (ARCP) for junior doctors, supervision and mentoring should provide a positive foundation for supporting staff who are thriving and for identifying others who may be struggling.

The GMC and BMA reports

The GMC identifies that public demand for care is rising in volume and complexity as the number of households and proportion of older people increase (General Medical Council 2018; Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Neal, Bhugra, Bell and Burns2016b; Williams Reference Williams, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019a, Reference Williams, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019b). It says doctors report that: the pressures are making it difficult to support each other; between 2 and 4% took leave of absence at least once a month; and 25% reported considering leaving the profession at least once a month. Nearly 40% of the doctors surveyed said that they had refused to do additional work in the past 2 years.

The BMA introduced its recent report (British Medical Association 2019) by observing that the NHS is the fifth largest employer globally. It conducted a survey by collecting self-reports from more than 4300 doctors and medical students. Box 1 provides a brief summary of key findings (which might, of course, be subject to selection error owing to the self-selected nature of this convenience sample).

BOX 1 Key findings from the BMA survey of the medical workforce across the UK in 2018

Of more than 4300 doctors and medical students who responded:

• 80% of doctors were at high/very high risk of burnout,a with junior doctors most at risk. Burnout was driven mostly by exhaustion rather than disengagement

• 27% of respondents reported being diagnosed with a mental health condition, and 7% said they were diagnosed in the previous year

• 40% of respondents reported currently suffering from a broader range of psychological and emotional conditions

• 90% of respondents stated that their current working, training or studying environment had contributed to their condition

• one in three respondents said they used alcohol regularly or occasionally

• awareness of how to access support from an employer or medical school was varied. Junior doctors were most likely to say they were not aware of how to access help or support

a. Burnout is a psychological syndrome that is characterised by overwhelming exhaustion, depersonalisation and reduced personal efficiency (Maslach Reference Maslach and Leiter2016).

(British Medical Association 2019: p. 4).

Figure 3 depicts a mix of primary and secondary workplace stressors that contribute to exhaustion and that healthcare staff commonly identify in our conversations with them. They comprise: rising demand, increasing expectations and limited resources; the impacts of organisations' cultures and their top-down responses to pressure; and exposure of staff to people's suffering and complex needs.

FIG 3 The triad of workplace stress (© R. Williams & V. Kemp V 2019. All rights reserved).

Moral injury, moral distress and moral architecture

We have presented elsewhere an overview of the challenges faced by healthcare systems (Warner Reference Warner, Williams, Williams and Kerfoot2005; Williams Reference Williams, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019a, Reference Williams, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019b). There are substantial tensions between patients' preferences, the ways in which many frontline staff wish to deliver care and what can be delivered. Staff caught in these tensions are at a real risk of becoming morally distressed and exhausted and, potentially, injured.

The construct of ‘moral injury’ originated in military populations. More recently, the construct has been extended to healthcare and to healthcare staff (Maslach Reference Maslach and Leiter2016; Murray Reference Murray, Krahé and Goodsman2018; Griffin Reference Griffin, Purcell and Burkman2019). The term has been used to describe the psychological sequelae of ‘bearing witness to the aftermath of violence and human carnage’ (Litz Reference Litz, Stein and Delaney2009: p. 700) and encompasses witnessing human suffering, or failing to prevent outcomes that transgress deeply held beliefs, such as the rights of a child to be protected by their parents, or the belief that life can and should be preserved by appropriate and timely medical intervention. It also recognises failings in leadership, where staff are not appropriately resourced whether in terms of people, space or equipment.

Moral injury is distinct from moral distress, which describes circumstances in which staff are unable to deliver the level of care they would like to owing to structural constraints. The issues of failures in leadership, and the types of injury/illness treated in pre-hospital settings, hospitals and communities, are linked to psychosocial distress in healthcare practitioners. In this context, moral distress arises because the aspirations of staff to deliver high-quality care are not realised owing to limitations in the quality of care that services can support. In our experience, this notion resonates strongly with staff. Conversely, clinicians' satisfaction with their relationships with patients can protect them against professional stress, substance misuse and even suicide attempts (Shanafelt Reference Shanafelt2009).

Employers have moral as well as legal responsibilities for their staff. The notion of ‘moral architecture’ refers to the moral and human rights obligations that organisations acquire as employers and through their commitment to delivering high-quality services (Williams Reference Williams2000). We argue that it is difficult for healthcare staff to continue to provide compassionate, evidence-informed and values-based care for their patients if they are not supported by their employers or if there is dissonance between the support, training and care for staff and the quality of care that they are expected to deliver (Williams Reference Williams and Fulford2007). This is especially so when employers ask staff to take more than minor risks when discharging their (the employers') responsibilities.

These obligations should be reflected in organisations' policies, their design and delivery of services, and their corporate governance (Warner Reference Warner, Williams, Williams and Kerfoot2005). Thus, the ways in which organisations recognise the needs of, and care for, their staff reflects their moral architecture (Williams Reference Williams2000). We contend that healthcare organisations must better understand the needs of their staff and provide effective leadership, support and care to enable staff to continue to consistently deliver compassionate care for their patients. In the next section, we summarise several of the many elements of this.

Delivering compassionate healthcare

Emotional labour

Healthcare staff feel satisfaction when their work produces positive feelings about not only helping particular people but also contributing to society's greater good (Stamm Reference Stamm and Figley2002). Emotional labour, described by Hochschild (Reference Hochschild1983: p. 7) as involving the suppression of feeling in order to sustain an outward appearance that produces in others a sense of being cared for in a safe place (a definition explored by Smith & Cowie (Reference Smith and Cowie2010)), is a key element in ensuring compassionate care. But it is not routinely acknowledged as important in healthcare staff's roles. However, without that labour, it is unlikely that the quality of care that people receive will be of the highest. Thus, we assert that quality of care, compassion and emotional labour are closely linked.

The majority of staff develop a range of coping strategies, both active and passive, to enable them to continually meet the challenges work presents, including strategies to address secondary stressors. However, some protective responses, such as numbing their feelings in an attempt to cope, may lead staff using them to be perceived by colleagues and patients as cold, detached and dispassionate (Hochschild Reference Hochschild1983). This restriction of feelings is a form of behaviour commonly noted after serious events and, for example, among ambulance personnel who are experiencing burnout and compassion fatigue and in work cultures that support shaming and blaming (Clohessy Reference Clohessy and Ehlers1999; Cicognani Reference Cicognani, Pietrantoni and Palestini2009; Clough Reference Clough2010). Staff who hold onto their feelings are likely to have greater difficulty coping with traumatic experiences (Cicognani Reference Cicognani, Pietrantoni and Palestini2009).

Social support

Research from Haslam et al (Reference Haslam, McMahon and Cruwys2018) indicates that people, generally, seriously underestimate the importance of social factors for health. They report meta-analytic results indicating that social support and social integration are highly protective against mortality, and that their importance is comparable to, or exceeds that of, many established behavioural risks, such as smoking, high alcohol consumption, lack of exercise and obesity.

Inadequate social support may contribute to the risk of healthcare staff developing mental disorders both directly and indirectly through staff being part of a wider dysfunctional work environment (Blanchard Reference Blanchard, Hickling and Mitnick1995). The degree of stress that ambulance clinicians, for example, face in their work as a result of aspects of organisational culture seems to be a bigger contributor to their levels of anxiety and depression than the demanding incidents to which they respond (Hochschild Reference Hochschild1983). The power of interactions between persons and groups of people, including work colleagues, and among healthcare staff contributes to job satisfaction (Cicognani Reference Cicognani, Pietrantoni and Palestini2009). Thus, social and relationship factors must be considered cultural foundation stones of each organisation's moral architecture.

Groups and teams

Many staff of healthcare and other services have spoken to us of the importance of their relationships at home and at work to their coping with the stresses and strains of working within the triad of workplace stress (Fig. 3) that is all too common in high-demand environments. They recognise the importance of their peers, but also say that one of the most challenging stresses can be organisational cultures in which they and colleagues may be undermined and belittled when they offer different ideas or ask questions about current practices in patient care. This raises several matters relating to teams and people's relationships within them.

The term ‘team’ – a group of people with a shared and agreed set of aims and goals and a shared identity – is often used to describe groups of people who work together within an organisation (Shuffler Reference Shuffler, DiazGranados and Salas2011). But many teams are not teams by this definition, especially if employers have not defined explicitly what kind of team they require (Carter Reference Carter, West and Dawson2008). Reicher (Reference Reicher, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019) identifies the important components of the definition of team membership. Crucially, there must be a sense of shared identity and not just linkages based on knowing and working with one another over a period of time. This sense of shared identity creates a secure base from which to manage working environments and it unlocks the potential of group members.

Central to each group's ability to cope is the concept of emotional containment, whereby strong emotions can be held or contained by a team, group or system without members realising (Bion Reference Bion1961). This process can be supportive and foster exploration of other difficult emotions while making members feel safe. But Campling (Reference Campling2015) describes ‘perverse dynamics’, that is, a range of behaviours leading to escalation and conflict that become real challenges to the health of the social climate of work systems. These dynamics may serve to corrosively undermine both personal and team well-being.

In general, leaders have important and positive effects on the well-being of individual staff members and teams, if they have the appropriate emotional capability and capacity. Leaders should consider the health and shared identity of each team for which they are responsible in order to create and sustain true teams that have sufficient stability to achieve their purposes.

Psychological safety

Most people recognise that their working environment is a hugely important aspect of organisational culture. Psychological safety is one component of organisational and team culture that separates blame, belittling and undermining from constructive learning that has substantial effects on staff well-being. Edmondson (Reference Edmondson, West, Tjosvold and Smith2003) says that ‘in psychologically safe environments, people believe that […] others will not resent or penalize them for asking for help, information or feedback’. There is an important role for leaders in creating working environments that are as psychologically safe as possible. Furthermore, Bleetman et al (Reference Bleetman, Sanusi and Dale2012) found evidence that staff who work in high-risk specialties, such as emergency departments, make fewer mistakes if human factors are sufficiently taken into account. Thus, psychological safety benefits staff and their patients.

A good predictor of both well-being and sickness absence is the quality of the relationship between leaders and their staff (Black Reference Black and Frost2011). Rousseau (Reference Rousseau1989) used the term ‘psychological contract’ to describe an often unacknowledged relationship between staff and the organisations for which they work. Breaches in these contracts can move staff from feeling motivated and willing to cope with challenges to feeling the opposite, with a likely impact on their morale, motivation and productivity. Staff are very aware of work-related experiences that they perceive as being unjust and that damage ‘good enough’ psychological contracts. Thus, the concepts of psychological safety and organisational justice are relevant to moral injury and organisations' moral architecture (Adams Reference Adams1963; Barsky Reference Barsky and Kaplin2007). Fortunately, it is possible to reduce the likelihood of breaches occurring and also to repair them.

All of these factors can be seen in effective human relationships and are equally important in healthy organisational relationships. We argue that organisational cultures that avoid or deny problems are dangerous and can create and maintain toxic social climates wherein individual members of staff are increasingly blamed for what may be essentially systemic problems (Wilde Reference Wilde2016). These systems also focus on solutions that concentrate on removing or curing ‘bad’ or ‘sick’ members of staff. Toxicity and attribution styles of this nature have been identified in all of the recent inquiries into failures of care.

Psychosocial resilience

It is common for staff and organisations to talk of ‘resilience’, but too often that construct is poorly defined and examined or is seen as trait-based and not transactional. Elsewhere, we have written in detail about the nature of resilience and the account here is but a short abstract (Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Alexander, Ryan, Hopperus Buma and Beadling2014, Reference Williams, Kemp, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019c, Reference Williams, Kemp, Crome and Williams2019d).

In a blog for The BMJ, Ripullone & Womersley (Reference Ripullone and Womersley2019) have critiqued the training in resilience that the GMC now requires. They direct attention to medical students in the UK now having to receive formal resilience training, but are critical of it at theoretical, policy and practical levels. They see it as top-down, say that ‘resilience is most problematic when presented as a form of self-care’ and ask if it is really a trainable skill.

We agree with each of these opinions – they fit with the findings from our own work. Often, we have found the adjective ‘resilient’ used to describe people who cope despite the pressures they face. The term also risks misuse because it implies that responsibility for staff coping lies substantially with the staff themselves rather than it being a systemic organisational feature. A better approach is to identify factors about people and organisations that keep them well when they are faced with pressure and stress. In their systematic review of resilience in communities, for example, Patel et al (Reference Patel, Rogers and Amlôt2017) found three general types of definition:

• ‘process’ definitions (i.e. an ongoing process of change and adaptation)

• ‘absence of adverse effect’ definitions (i.e. an ability to maintain stable functioning)

• ‘range of attributes’ definitions (i.e. a broad collection of response-related abilities).

In our experience, absence of adverse effect is the dominant use, but we concur with Patel et al that process definitions are being more commonly used now. Kaniasty & Norris (Reference Kaniasty, Norris, Ursano, Norwood and Fullerton2004) and Norris et al (Reference Norris, Stevens and Pfefferbaum2008, Reference Norris, Tracy and Galea2009) define resilience as a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disturbance. This is our preferred definition and we agree that ‘it is better to avoid using simple, reified, and static definitions of […] resilience […] since they lack explanatory power, as well as clear directions for future action in preparedness and response’ (Ntontis Reference Ntontis, Drury and Amlôt2019).

Core features of people who show good psychosocial resilience are that they: perceive that they have received, and objectively receive, social support; tend to show an accurate perception of reality; have belief in themselves that is supported by strongly held values; and have abilities to improvise (Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019c). Variations in the social factors that affect how people cope at work may well explain why the same people may respond differently in different circumstances. Thus, good psychosocial resilience is not about absence of short-term upset or brief distress, but how people adapt and recover after stressful events. A number of factors determine what psychosocial resources members of staff may have at their disposal (Bakker Reference Bakker and Demoerouti2007). These may include their attachment patterns, personalities, relational styles, sense of agency, beliefs and tolerance of distress. But, to return to an earlier theme, there is strong and consistent evidence that shared social identification with groups of people (in this instance, work colleagues and families) is an important predictor of health (Junker Reference Junker, van Dick and Avanzi2018). Shared social identification is positively related to perceived social support, which is associated with collective efficacy (Fig. 2).

Conversely, the value of these psychological resources may well be limited by other psychological factors, such as people's and organisations' self-defeating coping strategies. Self-awareness, that is the ability to understand one's own internal or psychological world, is an important resource. Professional promotion of greater self-awareness through reflective practice has been a major advance across the caring professions, but its utility as a resource has yet to reach its potential (Jayatilleke Reference Jayatilleke and Mackie2013). Taking a closer look at yourself can form an important part of personal as well as professional growth (Bailey Reference Bailey, Curtis and Numan2001).

Deliberate system-focused interventions to promote reflection on the emotional impact of healthcare work are well illustrated by Balint groups (Salinsky Reference Salinsky2003) and Schwartz rounds (Pepper Reference Pepper, Jaggar and Mason2011), which can help to support teams' growth of self-awareness and reflective organisational working cultures. Balint groups may promote open discussion of emotion in relation to work, provide spaces for mutual support and understanding and, as a consequence, can create a sense of coherence and containment among group members. George reports that introduction of Schwartz rounds in some NHS organisations:

‘was associated with a reported upsurge in feelings of interconnectivity and compassion towards colleagues. More traditional forms of individualised staff support were in contrast, viewed as unhelpful. In particular, the offer of counselling sessions was resented by many staff because it carried the implicit message that the problem arose from a deficiency or weakness within them. New performance management policies compounded this problem and left many feeling blamed and punished for their stress’ (George Reference George2016).

Interventions of these kinds are increasingly popular and, once again, the power of a systemic balance of organisational and personal attributes and practices emerges.

We concur with Ripullone & Womersley (Reference Ripullone and Womersley2019) when they recommend that ‘The professionalism curriculum needs to be revised with a focus on resilient systems rather than resilient doctors. Workplaces would do better by defining resilience as a shared value rather than an individual asset’. Thus, we have taken a systemic and transactional approach to developing a plan for care of health services staff.

Meeting the needs of staff

Our work has shown that people respond to stress by mobilising their inner, personal resources; in parallel, the support provided by their families, colleagues, friends, the people with whom they are in contact and employers is critically important. Together, these resources enable people, families and communities to generate ‘adaptive capacities’ that help them to cope reasonably well, recover from events and learn lessons for the future. Thereby, personal and group processes come together to underpin psychosocial resilience. Resilience emerges when people interact as members of groups. As Drury & Alfadhli (Reference Drury, Alfadhli, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019) show, these relationships may also arise emergently in crises when groups of people thrown together by events share a fate that promotes sharing of social identity.

Social connectedness and social support are two of the most powerful influences on health. Organisations that can create the conditions, including time, for social connectedness are better able to support staff. In healthcare services, work patterns may have positive or negative valencies, depending on whether practitioners see them as sources of stimulation and satisfaction or of challenge and obstruction. These attitudes are heavily influenced by fatigue, staff's past experiences of employers' approaches to and care for their staff, and how employers handle institutional processes, including clinical and corporate governance. Together, these matters powerfully tone organisational culture. The model proposed for Health Education England by the National Workforce Skills Development Unit (2019) includes many of the matters covered in this article in its framework for reducing workforce stress. Employers may mitigate or accelerate the challenges that their staff face and influence how staff experience similar demands if they attend to the matters we cover.

But, instead, the GMC report (2018) finds that doctors are resorting to four ways of dealing with pressure. They are:

• using smarter ways of working to manage workloads – the GMC is concerned that the limits of smarter working have been reached

• prioritising certain aspects of clinical service and patient care at the expense of other activities – the GMC is concerned that this results in practitioners withdrawing from continuing professional development (CPD), for example

• changing the type of work they do, such as working outside their grades or levels

• adopting strategies that prioritise immediate patient care and safety, including making unnecessary referrals.

The GMC is concerned about the impacts of these strategies. It reports that doctors would like: more support, including from work-based systems; mentoring from colleagues and senior managers; prioritisation of their health; and protection of CPD and other non-clinical activities.

The NHS has recently published its ‘Interim NHS People Plan’, because ‘we […] must take action immediately […] while we continue our collaborative work to develop a costed five-year People Plan’ later in 2019 (NHS Improvement 2019: p. 8). It sets six objectives, which are to:

• make the NHS the best place to work

• improve its leadership culture

• prioritise urgent action on nursing shortages

• develop a workforce to deliver ‘21st-century care’

• develop a new operating model for the workforce

• take immediate action in 2019–2020 while it develops a full 5-year plan.

In our opinion, sustaining healthcare staff requires every healthcare organisation to have a plan at both strategic and operational levels. This is in line with the Stevenson/Farmer Review (Stevenson Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017), which makes the recommendations for employers summarised in Box 2.

BOX 2 Recommendations for employers of the Stevenson/Farmer Review

• Produce, implement and communicate a plan for mental health at work

• Develop mental health awareness among employees

• Encourage open conversations about mental health and the support available when employees are struggling

• Provide employees with good working conditions

• Promote effective people management

• Routinely monitor employee mental health and well-being.

(Stevenson Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017: p. 8).

In the next two sections, we add other imperatives for action by healthcare employers, including good leadership, attending to organisational culture and providing peer support (Varker Reference Varker and Creamer2011), and offer a stepped framework for planning that titrates actions and services against staff's needs.

Leadership

Leadership is a complex array of values, attitudes, qualities, perceptive skills and transactional and translational capabilities that creates and communicates a vision of tasks. Leadership stands as one of the most important factors that are vital to keeping staff healthy and their work effective (Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Neal, Bhugra, Bell and Burns2016b). Research shows, as examples, the effect of good leadership on mental health and well-being for various groups, including PhD students and military personnel (Kuoppala Reference Kuoppala, Lamminpää and Liira2008; Jones Reference Jones, Seddon and Fear2012; Rona Reference Rona, Jones and Sundin2012).

Leaders play important roles in fostering environments that contain their staff's emotions in ways that are realistic and safe. Necessarily, this requires team leaders to be acutely aware of team members' training and ensure they receive professional supervision, effective management and psychosocial support. Leadership takes many forms. One of them is civility. Recurrently, we have been reminded when talking with junior medical staff that apparently small acts, in which consultants recognised the clinical challenges they had faced, and expressions of kindness are experienced positively and enhance the appreciation of consultants as leaders. Junior doctors have commented to us about consultants introducing themselves by their first names, which creates what one person described as ‘a lovely open and approachable learning and working environment’. Another person has described to us how a couple of days after a particularly difficult shift, it was good that a senior colleague had asked how they were and appeared genuinely concerned to hear the answer. Thus, civility in workplaces, including clinical settings, is important. Civility Saves Lives claims that civility improves diagnosis, clinical decision-making and patient outcomes (https://www.civilitysaveslives.com/academic-papers-1).

Our suggestions about the qualities of leaders who are able to create psychologically safe and resilient healthcare teams are summarised in Box 3.

BOX 3 Qualities of leaders

Creating and running psychologically safe teams and sustaining the resilience of healthcare staff requires leaders to:

• be accessible and supportive

• acknowledge fallibility

• balance empowering other people with managing the tendencies for certain people to dominate discussions

• balance psychological safety with accountability, safety and other components of strategic and clinical governance

• guide team members through talking about and learning from their uncertainties

• balance opportunities for their teams' reflection with action

• have the capacity for emotional containment/holding.

(Williams Reference Williams, Kemp, Neal, Bhugra, Bell and Burns2016b)

Other important factors include providing sufficient resources, adequate peer support, and adequate information about events, tasks and situational factors, and ensuring effective professional and managerial supervision.

A framework for action

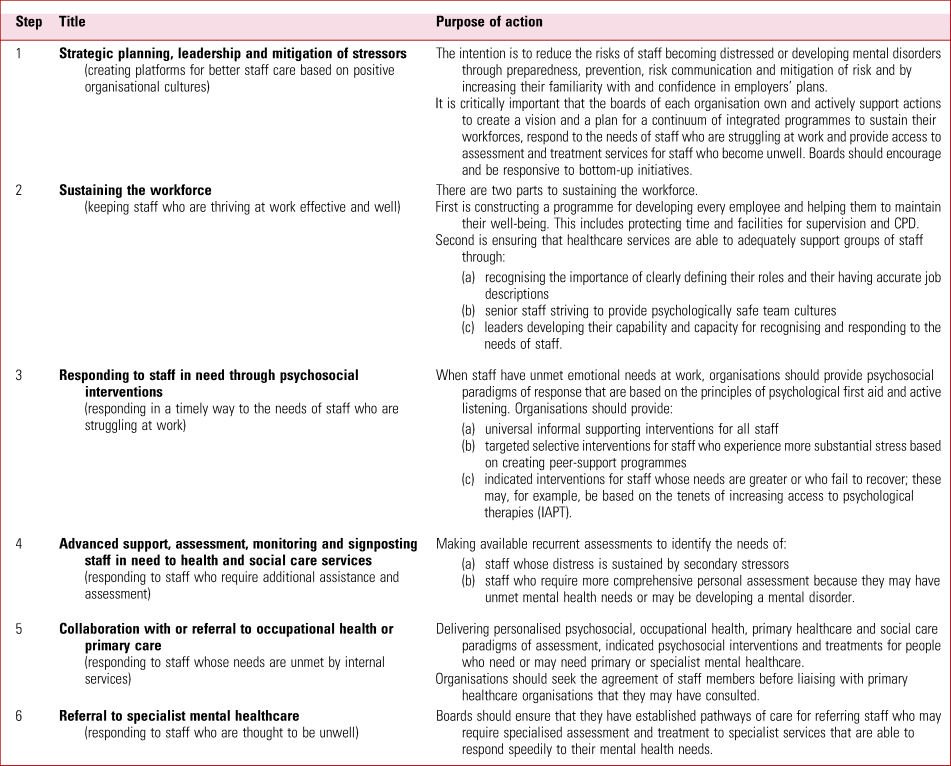

The evidence cited in this article establishes the imperative for improving the ways in which commissioners, managers and clinical leaders develop, care for and lead staff. This article provides insights into the many actions required to create a comprehensive strategy for caring well for staff of healthcare services. The authors of this paper propose a framework for how leaders and managers could organise their thinking and actions to create interventions that offer the benefits of leadership, psychologically safe teamwork and social support in order to assist healthcare staff to deliver effective, compassionate care in ways that fit with the three challenges in the Stevenson/Farmer Review (Fig. 1) (Stevenson Reference Stevenson and Farmer2017). Our model is summarised in Table 1 and Fig. 4. The numbers in Fig. 4 refer to the steps in Table 1.

FIG 4 The stepped care model for staff. (© R. Williams & V. Kemp 2019. All rights reserved.)

TABLE 1 A stepped model of care for healthcare staff

© R. Williams & V. Kemp 2019. All rights reserved.

This approach fits with: the opinions of doctors about the way forward reported by the GMC (General Medical Council 2018); the findings from the BMA survey (British Medical Association 2019); and recent NHS England guidance relating to major incidents that is applicable across all specialties and circumstances (NHS England 2018). It recognises the three challenges identified by Stevenson & Farmer.

We think that mental health services could play important roles in modelling plans of the nature that we describe. Furthermore, their expertise is such that senior staff in all disciplines could provide advice to their colleagues in other organisations about how they might proceed. Importantly, we identify in this article a continuum of responses for healthcare staff that builds on every staff member's day-to-day experiences but includes facing the possibility that a small number may become ill and require mental health assessment and, possibly, treatment. Senior staff of mental health provider organisations should be ready and enabled by commissioners and/or service-level agreements to deliver these services. We believe that every healthcare organisation should establish care pathways that enable their staff to receive the specialist mental healthcare they require in timely ways.

Conclusions

This article recognises the pressures that are falling on the staff of healthcare services; arguably, the National Health Services for each constituent country of the UK are now in a chronic state of gross overtasking. We recommend that all policies and strategies should articulate not only vision – comprised of a statement of intent, a clear direction for actions to deliver the envisioned service and clarity about the values on which that vision is based – but also a plan for developing and sustaining organisations and their staff (Box 4). Organisations should attend to their moral architecture if they are to sustain their staff. As a report from the Royal College of Physicians explains, investment in healthcare staff is not an optional extra, but a vital investment in safe, sustainable patient care. It says, ‘There is an inextricable link between levels of engagement and wellbeing among NHS staff, and the quality of care that those staff are able to deliver’ (Royal College of Physicians 2015: p. 10).

BOX 4 Key messages regarding caring for health service staff

• Working with people in crisis or who are ill is an unusual job that is rich in social meaning and value, but it requires emotional labour

• This work calls for strength and self-possession but creates fatigue. Staying calm, and not being able to distance oneself from what is happening to patients, can be stressful and may make it difficult for staff to leave their experiences behind subsequently

• Supporting and leading staff appropriately may enhance their satisfaction, reduce the risks to their health and sustain services for the benefit of patients

• Staff caught in the tensions of trying to deliver high-quality care in healthcare systems that are under continuing pressure are at risk of moral distress

• Organisations acquire responsibilities for the health and well-being of their staff and whether or not they take active steps to develop and support their employees is an important aspect of their moral architecture

• Employers should adopt a stepped approach to developing and caring for their staff that is based on titrating the interventions offered against employees' needs

• Important components of care include:

• universal supporting interventions that should be available to everyone

• targeted interventions that should be available to staff who are at increased risk of suffering the consequences of stress

• indicated interventions for staff who require more intensive support

• rehearsed routes of access to specialist mental healthcare for staff who become ill

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Adrian Neal, Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Head of the Employee Wellbeing Service in the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, NHS Wales, and Professor David Lockey, National Director of EMRTS Cymru and Chair of the Faculty of Pre-Hospital Care in the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, for their contributions to developing the authors' thinking.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 Secondary stressors that healthcare staff experience:

a are unrelated to the conditions in which they work

b describe stress that is directly related to the nature of the work they do

c exclude the circumstances and relationships that they experience at home

d include decisions that they think are unfair

e rarely influence the burden that they feel.

2 Lack of social integration and social support:

a have little influence on how staff cope with stress at work

b have effects on mortality that are comparable with smoking, high alcohol consumption and obesity

c are unlikely to contribute to the risk of healthcare staff developing a mental disorder

d are generally much less influential on the mental health of staff than the nature of the tasks that they undertake

e are a defining feature of teams.

3 Resilience:

a is entirely related to people's personal capabilities

b best describes the absence of adverse effects of untoward or challenging events

c is not an appropriate term to apply when a person suffers short-term distress after an untoward event

d is a process that links a set of adaptive capacities to positive functioning after a disturbance

e is unlikely to vary in the same person over time and when they are engaged with different teams.

4 Moral distress:

a is the direct impact on staff of not having access to occupational healthcare services

b only results from the long-term effects of being exposed to patients with mental illness

c does not occur in the medical profession

d describes teams having differences of opinion about ethical decisions

e may describe the effects on staff of their aspirations for delivering high-quality care not being realised.

5 According to Reicher (Reference Reicher, Williams, Kemp and Haslam2019), a team can be defined as a group of people:

a who have a sense of shared identity and an agreed set of aims and goals

b who work together in the same organisation over a period of time

c who work together despite their organisation not having established what kind of team is required

d who work together without need for a leader

e who require outside support to manage strong emotions.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 b 3 d 4 e 5 a

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.