Gait impairments such as freezing of gait (FOG) and postural instability are frequently described in corticobasal syndrome (CBS) patients. Reference Giagkou and Stamelou1 CBS parkinsonism is typically levodopa resistant, and there are currently no effective treatments or any disease-modifying therapies. Reference Giagkou and Stamelou1 Thus, there is a significant unmet need for an effective gait therapy. Tonic spinal cord stimulation (SCS) has shown significant promise for improving gait impairments and reducing FOG episodes in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients with levodopa-resistant gait difficulties. Reference Samotus, Parrent and Jog2,Reference Rohani, Kalsi-Ryan, Lozano and Fasano3 As these axial gait features are also observed in CBS, the effect of SCS was investigated over 12 months in a convenience sampling of two CBS participants (~3 years with disease) who had significant gait impairment while OFF- and ON-levodopa medication.

This monocentric, investigational, pilot study was approved by the Western University Research Ethics Board (REB#107451) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03079310). Participants recruited from the London Movement Disorders Centre provided signed informed consent. Due to the limited availability of SCS devices allocated for off-label use in our center, we explored the use of SCS in two participants with clinically certain CBS that met international criteria, Reference Grijalvo-Perez and Litvan4 resistant gait disorder, and significant FOG. Neither participants had a history of stroke, spinal disorders nor any other neurological diseases, significant cognitive impairment, chronic back and/or lower limb pain and were not on unstable pharmacological treatment. Although physiotherapy (PT) regimes were not part of the study protocol, PT was not effective for gait in either participants. However, prior to study recruitment, Case I continued in-home PT for home safety and range of motion exercises. Endpoints were assessed before surgery and at 3, 6, and 12 months of SCS use while OFF (≥12 h) and ON (150% of usual morning dose) levodopa. Primary endpoint was the change in spatiotemporal parameters (STPs) during self-paced walking on the ProtoKinetics Walkway. Sensors embedded in the walkway detect footfalls in real time which are captured by the Protokinetics Movement Analysis Software (PKMAS) program. PKMAS provides accurate and validated measurements of various gait parameters. Gait asymmetry and variability (CV%) values were calculated by averaging step length and stride velocity measures. FOG episodes were analyzed using foot pressure changes as previously described. Reference Samotus, Parrent and Jog2 Secondary endpoints were MDS-UPDRS part III, comprehensive apraxia upper limb assessment, Reference Leiguarda, Merello, Nouzeilles, Balej, Rivero and Nogués5 freezing of gait questionnaire (FOG-Q), and activities-specific balance confidence scale (ABC). Reference Samotus, Parrent and Jog2

Two electrodes with eight contacts/lead (Boston Scientific® Precision Novi) were implanted in the medial, epidural space of T8-T10 spinal segments. Reference Samotus, Parrent and Jog2 Electrode localization was confirmed by paresthesias fully covering the lower trunk, both lower extremities and feet. Reference Samotus, Parrent and Jog2

Starting one-week post-surgery, participants (ON-levodopa) were blinded to the testing of six SCS program combinations (pulse widths: 300 and 400 µs; frequencies: 30, 60, and 130 Hz) over two study visits; SCS device was switched on for 1-hour per setting. During gait assessments, SCS was programmed to a medium suprathreshold intensity (~3–5% higher intensity than paresthesia threshold adjusted while participant was seated). Reference Rohani, Kalsi-Ryan, Lozano and Fasano3 Following SCS programming, participants used the device daily (~10–14 h/day) set to a comfortable suprathreshold intensity. Reference Rohani, Kalsi-Ryan, Lozano and Fasano3

Mean and percent change of clinical symptoms, STPs, and FOG episodes were evaluated from pre-surgery to 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months of SCS use for each participant.

Both participants could not stand independently and required assistance for all daily activities. Case I, a 71-year-old woman presented with a predominant right foot drag and shuffling left foot. At baseline, Case I was able to walk half (10-feet) of the carpet and during post-SCS assessments completed two trials across the 20-foot carpet. Case II was a 62-year-old gentleman with complete gait failure and could not initiate stepping motion while standing and thus no gait measures could be collected. Study demographics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographics and clinical rating scores for Cases I and II while OFF- and ON-levodopa medication states at presurgery (baseline), 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months of SCS use

3m = 3 months; 6m = 6 months; 12m = 12 months; FOG-Q = freezing of gait questionnaire; UPDRS = unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale.

ON-Levodopa was not collected for Case II at 12 months.

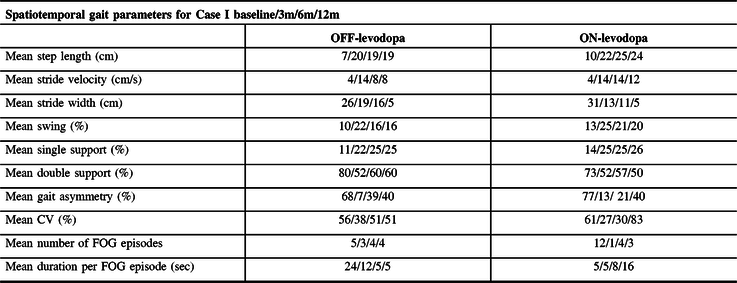

Case I’s gait improved on all six settings, with best outcomes on 300 µs/60 Hz (Supplementary Video 1). Mean step length, stride velocity, swing, and single support gait phases improved by a mean 100.3%, and the number of FOG episodes was reduced by 50%. After 3 and 6 months of SCS use while ON-levodopa, further improvements were observed with a mean 135.7% increase in gait measures and a 91.6% FOG reduction (Table 2). At 12 months, spatiotemporal gait measures were maintained; however, FOG duration and gait variability worsened by 236.5% and 38.3%, respectively. Confidence (ABC scale) improved by 78.6% at 3 months (Table 1). FOG-Q and apraxia improved by 62.5% and 27.7%, respectively, and total UPDRS-III score worsened by 10.3% (ON-levodopa) at 12 months. Clinical effects of SCS were also noted by Case I’s family and caregivers who mentioned the significant improvement in mobility while using a walker around the house, where ultimately Case I was able to travel to Florida during the winter months. No change in clinical symptoms or mobility post-SCS was seen in Case II (Table 1). No adverse effects were reported during the conduct of the study.

Table 2: Spatiotemporal gait features of Case I in OFF- and ON-levodopa medication states at presurgery (baseline), 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months of SCS use

3m = 3 months; 6m = 6 months; 12m = 12 months; CV = coefficient of variability; double support % = double support time expressed as a percentage of the gait cycle time; FOG = freezing of gait; Sec = seconds; single support % = single support time expressed as a percentage of the gait cycle time; swing % = swing time presented as a percentage of the gait cycle time.

Gait parameters could not be collected for Case II due to participant’s inability to produce a stepping motion.

This is the first study to date to report pilot evidence of the effect of SCS to improve pace and rhythm of gait and to reduce FOG, as demonstrated in one of the two CBS participants. SCS effectiveness may depend on the phenotypic features of the patient as Case II with gait failure showed no response to SCS. PT alone rarely improves mobility in CBS; however, PT sessions combined with SCS therapy may be useful. Continued improvement in FOG duration and gait variability in Case I when OFF-levodopa at 12 months. However, these measures worsened when Case I was ON-levodopa. This suggests levodopa induced a worsening effect on FOGs and this coincided with little to no motor response after the OFF-/ON-levodopa challenge. Recognizing the short disease course of CBS, disease progression is expected, and new symptoms such as bilateral inward foot posturing, dystonia affecting both lower limbs (requiring botulinum toxin type A injections), and ultimately reducing stride width and challenging ambulation. Study was limited by the number of available devices, limiting the number of patients implanted in this study, and by the lack of objective analysis of mobility/FOG in-home as FOG is an episodic phenomenon influenced by environmental triggers. Although this is a single case, the results demonstrate value in further studies to investigate whether SCS can be an effective FOG intervention early in CBS disease course (prior to complete gait failure). Reference Rohani, Kalsi-Ryan, Lozano and Fasano3

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution by the participants and by the research personnel and volunteer staff at the Parkinson’s Foundation Centre of Excellence, London Movement Disorder Centre located within the London Health Sciences Centre, London, Ontario, Canada. The authors would also like to extend recognition to the neurosurgical team of Dr. Andrew Parrent in the planning and coordination of this study at University Hospital, London Health Sciences Centre.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Jog also is a scientific advisor and receives research financial support from the following companies: AbbVie, Allergan Inc., Boston Scientific, Ipsen, MDDT Inc., Medtronic, Merz Pharma, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Parrent and Ms. Samotus report no conflict of interests.

Statement of Authorship

OS, AP, MJ: study concept or design. OS, AP, MJ study supervision or coordination. OS, AP, MJ: writing/revising content of manuscript. OS, AP, MJ: analysis or interpretation of data. N/A obtaining funding.

Ethical Compliance Statement

The authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was required for this work. We also confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2020.143.