Methods of synthesizing qualitative research studies for health technology assessment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 October 2011

Abstract

Objectives: Synthesizing qualitative research is an important means of ensuring the needs, preferences, and experiences of patients are taken into account by service providers and policy makers, but the range of methods available can appear confusing. This study presents the methods for synthesizing qualitative research most used in health research to-date and, specifically those with a potential role in health technology assessment.

Methods: To identify reviews conducted using the eight main methods for synthesizing qualitative studies, nine electronic databases were searched using key terms including meta-ethnography and synthesis. A summary table groups the identified reviews by their use of the eight methods, highlighting the methods used most generally and specifically in relation to health technology assessment topics.

Results: Although there is debate about how best to identify and quality appraise qualitative research for synthesis, 107 reviews were identified using one of the eight main methods. Four methods (meta-ethnography, meta-study, meta-summary, and thematic synthesis) have been most widely used and have a role within health technology assessment. Meta-ethnography is the leading method for synthesizing qualitative health research. Thematic synthesis is also useful for integrating qualitative and quantitative findings. Four other methods (critical interpretive synthesis, grounded theory synthesis, meta-interpretation, and cross-case analysis) have been under-used in health research and their potential in health technology assessments is currently under-developed.

Conclusions: Synthesizing individual qualitative studies has becoming increasingly common in recent years. Although this is still an emerging research discipline such an approach is one means of promoting the patient-centeredness of health technology assessments.

Keywords

- Type

- THEME: PATIENTS AND PUBLIC IN HTA

- Information

- International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care , Volume 27 , Issue 4 , October 2011 , pp. 384 - 390

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 2011

References

REFERENCES

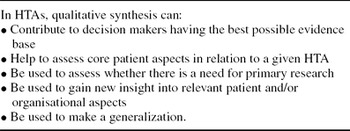

Table 1. Use of Qualitative Synthesis in HTAs (10)

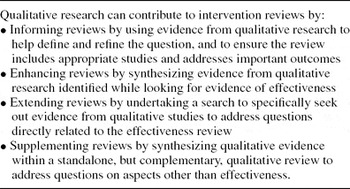

Table 2. Use of Qualitative Research in Intervention Reviews (17)

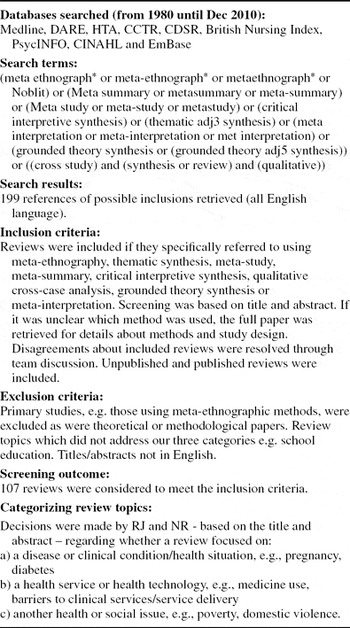

Table 3. Identifying Reviews Which Synthesised Qualitative Health Research Using One of the Eight Methods

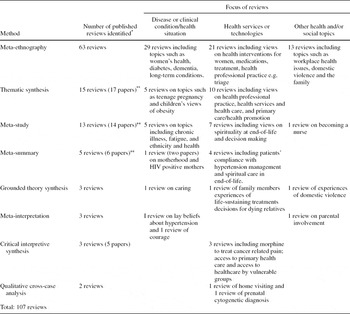

Table 4. Summary of Methods for Synthesizing Qualitative Research and Related Reviews (For Details Including Full References, See Supplementary Table 1)

- 64

- Cited by

To ensure that the needs, preferences, and experiences of service users are taken into account when developing and evaluating health technologies or care delivery models (Reference Facey4), health technology assessments (HTA) should take a patient-centered approach. One way of achieving this is by synthesizing individual qualitative research studies.

Qualitative research arose from several disciplines and traditions with various underpinning philosophies (e.g., phenomenology, see Supplementary Glossary, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011029) and data can be analyzed in different ways (e.g., using grounded theory). There is, therefore, no single approach or definition (Reference Mason14). While the underpinning philosophy may differ, qualitative research has some common characteristics. Generally, it refers to research exploring peoples’ experiences and understandings—the “hows” and “whys” of a social phenomena (Reference Malterud13). As such, qualitative research has a role in understanding the views of patients, or carers, of what it is like living with a particular condition and their experiences of health services or technologies.

Common qualitative data collection methods are observation, interviews, and focus groups, which produce textual data rich in meaning and insight. Data analysis usually involves inductive reasoning processes (hypothesis generating) to interpret and structure data/findings (Reference Thorne23). Influences on the qualitative data analysis process include the researcher(s) theoretical or philosophical “lens” through which they collect and understand their data (Reference Thorne23). Such influences, therefore, need to be considered when synthesizing qualitative research and assessing validity. Although the results from one qualitative study may be difficult to generalize, a syntheses of all the relevant qualitative studies can identify common themes and any divergent views.

The synthesis of qualitative studies has been encouraged recently, for example, within HTA (10) and systematic reviews of effectiveness (Reference Noyes, Popay, Pearson, Hannes, Booth, Higgins and Green17). Tables 1 and 2 suggest ways in which such syntheses can contribute to these processes. There is, however, no single approach to the identification and synthesis of health(-related) qualitative research and several methods are available. In our opinion, this range can appear over-whelming, even daunting, for those new to this field.

Table 1. Use of Qualitative Synthesis in HTAs (10)

Table 2. Use of Qualitative Research in Intervention Reviews (Reference Noyes, Popay, Pearson, Hannes, Booth, Higgins and Green17)

This study aims to provide some clarity by presenting the main methods for synthesizing the qualitative literature with a potential role in the HTA process. Although methods are discussed separately, in practice they overlap and are inter-related, with researchers often adapting principles of a specific method(s). Areas of debate also still exist, for example, whether it is appropriate, or feasible, to synthesize qualitative studies conducted from different epistemological perspectives (11). We present our interpretation of this complex body of literature.

METHODS

Having previously reviewed an extensive, but not exhaustive, body of literature to report on the eight main methods for synthesizing qualitative research (Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18), we now needed to identify reviews using each of these approaches (Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18). Nine electronic databases were searched during 2010 using relevant search terms (see Table 3 for details and inclusion criteria) to identify reviews conducted using: meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis, meta-study, meta-summary, critical interpretive synthesis, qualitative cross-case analysis, grounded theory synthesis, and meta-interpretation. For each of these methods, the titles and abstracts of potential reviews were screened by R.J. and N.R. working independently and then collaboratively to compare their findings. In cases of uncertainty, the full paper was retrieved. Each included review was then also broadly categorized (Table 3) according to its primary focus that is, whether it reported experiences and/or views on: (i) a disease, clinical condition or health(-related) situation; (ii) health services or technologies; (iii) other health and/or social topics.

Table 3. Identifying Reviews Which Synthesised Qualitative Health Research Using One of the Eight Methods

After identifying the number and type of reviews conducted using each method, we created a summary table to provide a visual representation of which of these methods of qualitative synthesis were being used and with what focus (Supplementary Table 1, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011029).

RESULTS

Identifying reviews conducted using these eight methods was challenging. There were many cases where the used method of qualitative synthesis was not explicitly articulated within the review title and/or abstract. Terminology was often used inconsistently and interchangeably. The term “meta-synthesis” was frequently used as a synonym for qualitative synthesis regardless of which method was used. “Meta-synthesis” could also refer to the whole review process including study identification, quality assessment and data analysis or specifically refer to the data synthesis element. Nonetheless, across the eight methods for synthesizing qualitative studies, we identified 107 reviews (Table 4, Supplementary Table 1).

Table 4. Summary of Methods for Synthesizing Qualitative Research and Related Reviews (For Details Including Full References, See Supplementary Table 1)

* Reviews were identified which reported using meta-ethnography, meta-study, meta-summary, thematic synthesis, grounded theory synthesis, meta-interpretation, critical interpretative synthesis, or cross-case analysis in title or abstract.

** Some reviews are reported in more than one paper by the same authors.

Use of the different methods across these 107 reviews varied. Table 4 demonstrates that reviews using critical interpretive synthesis, meta-interpretation, qualitative cross-case analysis and grounded theory synthesis were found infrequently. As the potential of these methods has yet to be fully established in the context of HTA, these are not discussed further here and readers are referred elsewhere for details (Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18). Meta-ethnography (Reference Noblit and Hare16), thematic synthesis (Reference Thomas and Harden22), and meta-study (Reference Thorne23,Reference Thorne24) were the most used methods (Table 4), especially on topics relating to health services/technologies and, whereas the number of reviews using meta-summary (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso20) were small, this method is of relevance to HTA. As such, we consider meta-ethnography, thematic synthesis, meta-study, and meta-summary to have a role in HTA, and these are outlined below with illustrative examples. Readers are referred to Supplementary Table 1 for references of individual reviews and the related theoretical guidance are recommended reading (Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18).

Meta-ethnography—derived from the work of Noblit and Hare (Reference Noblit and Hare16)—is currently the most common method for synthesizing qualitative health(-related) research—reflected in our finding of 63 reviews using this method. Meta-ethnography involves seven steps which, by bringing together findings from individual interpretive accounts, produces a new interpretation (Reference Noblit and Hare16). To synthesize these findings, meta-ethnography uses a variety of approaches including “reciprocal translation analysis” and “line-of-argument synthesis” (Reference Noblit and Hare16).

Most reviews using meta-ethnography were conducted in the 2000s by various healthcare disciplines. Twenty-nine reviews explored perceptions and experiences of disease and other clinical issues including eating disorders, diabetes, pregnancy, and childbirth. Twenty-one reviews explored views on health services/technologies including a range of medications/therapies. A further 13 reviews focused on health/social topics such as poverty and domestic violence (Supplementary Table 1).

One example (Reference Malpass, Shaw and Sharp12) of interest to HTA reviewers aimed to enhance understanding of patients’ experience of anti-depressants. Sixteen papers met the inclusion criteria and were quality assessed before synthesis. Two groups of papers were identified—those which focused on the patient-doctor decision-making process and those with a focus on patients’ self-concept and notions of stigma (Reference Malpass, Shaw and Sharp12). The reviewers found that the initial diagnosis of depression may be associated with feelings of relief or despair and that patients’ preferences for engaging in decision making during their illness is a dynamic process. To improve adherence to advice regarding medication use during depression, it was suggested that GPs should take into account patients’ changing situations and sense-of-self during their treatment (Reference Malpass, Shaw and Sharp12).

Thematic synthesis is often (but not exclusively) used for analyzing qualitative data alongside quantitative data synthesis. Initially developed by researchers from the EPPI-Center, it addresses questions around “what works,” primarily in relation to health promotion interventions. Reviewers can synthesize qualitative and quantitative research separately then integrate their findings (Reference Thomas, Harden and Oakley21). Thomas and Harden's (Reference Thomas and Harden22) method develops analytical themes through descriptive synthesis and finding of explanations relevant to a particular review question (Reference Thomas and Harden22). This method was developed to address specific review questions about need, appropriateness, and acceptability of interventions, as well as effectiveness. Peoples’ views and experiences are taken into account, and hypotheses that could be tested against the findings of qualitative studies are generated. We identified 15 reviews—10 of these investigated topics relating to health services/technologies including health promotion, decision making in chronic kidney disease, and the patient–doctor relationship. Five reviews focused on understanding disease/clinical conditions such as lay understanding of cancer risks and mothers experiences of bottle-feeding (Supplementary Table 1).

An example of thematic synthesis of relevance to HTA is a study on adolescent experiences following organ transplantation (Reference Tong, Morton, Howard and Craig25). This study aimed to improve understanding of the psychosocial impact of transplantation from a wide body of research from different time periods, locations, and contexts. Eighteen papers met the inclusion criteria and data were extracted and synthesized from individual results sections to identify descriptive themes. Five themes were identified: redefining identity; family functioning; social adjustment; managing medical demands; and, attitude to the donor (Reference Tong, Morton, Howard and Craig25). The reviewers concluded that to ensure adolescent patients are able to deal with the multifaceted nature of their psychological response to transplantation, healthcare teams need to provide them with relevant skills and support (Reference Tong, Morton, Howard and Craig25).

Meta-study involves critical interpretation of existing qualitative research (Reference Bondas and Hall6). Before synthesis can take place and a new interpretation obtained, three analytical phases are completed—“meta-theory, meta-method, and meta-data analysis” (Reference Thorne24). These phases, equating to the analysis of theory, analysis of methods, and the analysis of findings (Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas5), can be conducted concurrently to “provide a unique angle of vision from which to deconstruct and interpret” a body of qualitative literature (Reference Bondas and Hall6). Once these analytical processes have been completed, meta-synthesis “brings back together ideas that have been taken apart,” creating a new interpretation of the phenomenon under investigation (Reference Bondas and Hall6). Our search identified thirteen reviews mostly published in nursing journals. Seven of these studies were potentially relevant to HTA reviewers for example, those focusing on shared decision making and spirituality in end-of-life care (Supplementary Table 1).

Edwards et al. (Reference Edwards, Davies and Edwards8) used meta-study to understand why shared decision making in healthcare was not being implemented and to develop a model of external influences on health information exchange. These reviewers identified three themes: internet information use; cultural differences in intercultural consultations; and the influence of the women's health movement (Reference Edwards, Davies and Edwards8). A range of external influences relating to the practitioner and/or patient were included in the model. These influences included receptiveness to patient empowerment, expression of cultural identity and role expectations while health information exchange was assisted where patients already had skills in sourcing and understanding basic health information (Reference Edwards, Davies and Edwards8).

Meta-summary uses “quantitatively oriented aggregation of qualitative findings that are themselves topical or thematic summaries or surveys of data” (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso20). Such summaries can be conducted on their own, or in association with more traditional qualitative synthesis, and can include qualitative and quantitative descriptive findings. Although the least used method presented here—we only identified five reviews on topics such as compliance with hypertension therapy, motherhood and HIV infection (Supplementary Table 1)—it is of relevance to HTA as meta-summary reflects a quantitative perspective and can be used with survey data which is often excluded from some qualitative synthesize due to lack of conceptual depth and richness.

Meta-summary has been used to explore the experiences of parents receiving a positive prenatal test result indicating pregnancy could result in a child with a disability (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso19). Seventeen qualitative studies of American women and/or their partners who received a positive prenatal test result were synthesized. Once data were extracted, findings were reduced to 39 meta-findings, which were ordered by their relative presence or prominence. The most prominent finding was that positive diagnosis is depicted as the experience of termination with an emphasis on parental choice and decision making (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso19). The reviewers suggest that healthcare services should support couples receiving a positive prenatal diagnosis to develop a “narrative of choosing” that can allow them to come to terms with their decisions post-testing (Reference Sandelowski and Barroso19).

DISCUSSION

One way of incorporating qualitative research and the perspectives of service users within HTAs is through synthesizing individual studies. Although some researchers in certain disciplines, especially nursing, have been synthesizing qualitative studies for some time, this approach has become increasingly common among a wider range of disciplines. The strength of qualitative research is its ability to provide personal insight into the phenomena being investigated but its perceived limitation has been the small number of participants and the inability to generalize findings. Being able to synthesize individual studies to produce a “stronger” body of knowledge has, therefore, become of critical importance if the full potential of qualitative research to inform practice and policy is to be realized.

Qualitative research and the synthesis of individual studies has a considerable role to play in HTA and policy making, as such insight and knowledge is one mechanism for ensuring these processes become more patient/carer-centered. The synthesis of qualitative studies enables reviewers and policy makers to understand what it is like for people to live with a particular long-term condition, experience the effects of medications and/or the process of health service delivery and new technologies. This insight is, therefore, invaluable to those conducting HTA as such knowledge can help explain why particular interventions work, or are unlikely to work, from the perspective of patients/carers—insight that is not possible through quantitative research and systematic review alone. However, there are several issues of relevance to those synthesizing qualitative research.

Searching for qualitative studies is more complex and difficult than searching for quantitative studies (Reference Barroso, Gollop and Sandelowski1) and is an under-developed area of qualitative review methodology (Reference Flemming and Briggs9). Some qualitative methods (such as those which mirror the quantitative systematic review approach) aim to be comprehensive, identifying all potential studies but other methods—such as meta-ethnography—may be more purposive, and aim to reach theoretic saturation rather than identify all relevant studies (Reference Noyes, Popay, Pearson, Hannes, Booth, Higgins and Green17). Use of inclusion criteria also varies depending on the reviewers’ underlying philosophical approach. For example, a qualitative synthesis conducted alongside a systematic review of quantitative studies, is likely to have well defined and explicit inclusion criteria (11). Whereas, a standalone synthesis of qualitative studies may include studies based on “conceptual robustness” and theoretical saturation (Reference Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young and Sutton2), perhaps adopting a more iterative approach to literature searching and screening.

Quality appraisal of included qualitative studies is not as straightforward as for quantitative studies. There is currently little consensus as to what are the essential criteria for a high-quality qualitative study and over 100 quality appraisal tools are available (Reference Noyes, Popay, Pearson, Hannes, Booth, Higgins and Green17). What constitutes quality in qualitative research is a contested area and part of a bigger debate over the nature of knowledge generation (Reference Mays and Pope15). Different disciplines may place a higher value on some aspects of study design such as the theoretical perspective or analytical strategy and there are concerns about excluding less well-conducted studies on the grounds of quality as they may still provide important new insights into a phenomenon (Reference Dixon-Woods, Sutton and Shaw3). Whereas some methods such as thematic synthesis have specific approaches to quality assessment, other approaches such as meta-ethnography are “less committed to the concept” of quality appraisal (Reference Barnett-Page and Thomas5).

Although we found 107 reviews across the eight methods for synthesizing qualitative research, use of these methods varied considerably, especially in topics relating to reviews of health services/technologies. Grounded theory synthesis, meta-interpretation, critical interpretive synthesis, and cross-case analysis have been used less often—generally and specifically on topics relating to health services/technologies—and their usefulness in the context of HTA has yet to be fully established (Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18). However, meta-ethnography, meta-study, meta-summary, and thematic synthesis have been more widely used and could have a greater role in HTA.

An earlier review of studies synthesizing qualitative research published between 1988 and 2004 reported that meta-ethnography was the most frequently used method (Reference Dixon-Woods, Booth and Sutton7). Our review indicates that meta-ethnography continues to be used most across a range of multi-disciplinary topics including investigations of health services and technologies and, as such, has consolidated its position as the leading method for synthesizing qualitative research. Whereas other methods, for example meta-study, have the potential for broader application they have been used less frequently across a narrower range of topics, often in nursing practice. Those synthesizing qualitative research tend to adapt methods to suit their studies (Reference Dixon-Woods, Booth and Sutton7;Reference Ring, Ritchie, Mandava and Jepson18) and the relevant terminology is used inconsistently and inter-changeably. This has implications for those synthesizing qualitative studies for use in HTA, especially during identification of included studies, as they should not assume original authors/researchers using the same or similar term, share the same definition or understanding of that term in practice. Consequently, a limitation of our study is that we may not have identified all relevant reviews conducted using each method due to ambiguous terminology and/or lack of information about methods in titles and abstracts. There is, therefore, an urgent need for a consensus among qualitative synthesizers regarding such terminology.

Synthesizing qualitative research can ensure the needs, preferences and experiences of patients/carers are reflected within the HTA process in two ways. First, standalone syntheses of qualitative studies can provide vital contextual information. For example if an HTA is being conducted on a new model of diabetes health service delivery, a qualitative synthesis on the topic of caring for a child with diabetes could help HTA reviewers better understand how that new service may or may not fit with how parents/carers currently manage the condition. Second, findings from qualitative syntheses can be integrated with findings from trial based systematic reviews or other quantitative evidence. This approach can contribute to the HTA process by providing a better understanding of the effectiveness of interventions, such as the seminal example of thematic synthesis which juxtaposed barriers and facilitators to healthy eating by children identified from qualitative studies with findings from evaluated interventions (Reference Thomas, Harden and Oakley21).

CONCLUSIONS

Synthesizing qualitative research is one mechanism for ensuring that patient/carer views and perspectives are incorporated into health service policy making and delivery. There is a considerable body of knowledge on this topic but this literature is complex as several methods exist, the field is still evolving and those synthesizing qualitative research may approach their studies from differing epistemological stances. From the many methods available, meta-ethnography and thematic synthesis appear to be the most useful to HTA reviewers but other methods, including meta-summary, may also be of benefit. Overall, the potential of these methods is yet to be fully realized in terms of using existing qualitative syntheses as contextual information for HTA and through integrating qualitative and quantitative review findings. Nonetheless, those conducting HTA and policy makers must recognize that incorporating the synthesis of qualitative literature into their work can add new insight and value. In particular, understanding that without taking into account the views of patients/carers when health services or technologies are being planned or policy agreed, new developments may not fit with patients’/parents’ preferences or needs. Whereas qualitative syntheses can be beneficial to those conducting patient-focused HTAs and quantitative systematic reviews by providing new insight, the challenge is how to routinely incorporate existing syntheses into their work and/or undertake their own such studies within, or alongside, the already time intensive HTA process. Those conducting syntheses of the qualitative literature must also take into account the benefits and limitations of qualitative research generally and debate about critical appraisal and literature searching more specifically (Reference Malterud13).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Glossary

Supplementary Table 1

www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011029

CONTACT INFORMATION

Nicola Ring, MSc, BSc, Dip HV, RGN, RSCN ([email protected]), Ruth Jepson, PhD, MSc, GN ([email protected]), School of Nursing, Midwifery & Health, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, Scotland, UK.

Karen Ritchie, PhD, MPH, BSc ([email protected]), Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Delta House, 50 West Nile Street, Glasgow G1 2NP, Scotland

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Karen Ritchie is employed by Healthcare Improvement Scotland (previously NHS Quality Improvement Scotland). Nicola Ring and Ruth Jepson received consultancy fees for this work from NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.