The eating context, defined as the situation in which people eat, involves immediate aspects related to each eating occasion and is an important determinant of both food nature and its intake(Reference Mak, Prynne and Cole1,Reference Fischler2) . This is resulted from the importance of context dependence on meal choices. Eating occasions and eating locations are intrinsically linked, and their complexity is reflected on the diversity of food choices(Reference Marshall and Bell3,Reference Yates and Warde4) .

In this sense, studies have investigated not only what people eat but also where and how they have a meal. Certain studies have focused on the availability and accessibility of unhealthy foods in the built environments, such as neighbourhoods and schools(Reference Azeredo, de Rezende and Canella5–Reference Shareck, Lewis and Smith7), while others assessed the home food environment(Reference Pearson, Griffiths and Biddle8,Reference Nishi, Jessri and L’Abbé9) . It is also known that the places of consumption were associated with different types of eating occasions among adults(Reference Liu, Han and Cohen10), whilst among children, the exposure to different eating contexts fomented the consumption of different fruits and vegetables(Reference Mak, Prynne and Cole1). However, little is known about the relationship between the patterns of eating context − considering multiple eating locations and social contexts − and ultraprocessed food consumption in adolescents, particularly at meal occasions.

Ultraprocessed foods are, according to the NOVA food classification system(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac11), industrial formulations of substances derived from foods (e.g. oils, fats, sugars, starch and protein isolates), which typically contain cosmetic additives (i.e. flavours and colours) and little, if any, whole foods. Soft drinks, flavoured dairy drinks, sweet or savoury packaged snacks, confectionery, breakfast cereals, packaged breads and buns, reconstituted meat products and pre-prepared, frozen or shelf-stable dishes stand out as some examples of ultraprocessed foods, which are increasingly available worldwide. They are convenient, extremely palatable, assertively marketed, attractively packaged and require little or no preparation(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Moubarac11). Its consumption has been associated with both unhealthy nutritional dietary quality(Reference Moubarac, Batal and Louzada12–Reference Martínez Steele, Popkin and Swinburn16) and diet-related diseases, such as obesity(Reference Canhada, Luft and Giatti17,Reference Rauber, Chang and Vamos18) , CVD(Reference Srour, Fezeu and Kesse-Guyot19), cancer(Reference Fiolet, Srour and Sellem20) and all-cause mortality(Reference Blanco-Rojo, Sandoval-Insausti and López-Garcia21–Reference Rico-Campà, Martínez-González and Alvarez-Alvarez23). In the UK, ultraprocessed foods account for more than half of the total dietary energy intake by the general population, representing up to 70 % of the total energy acquired by adolescents(Reference Rauber, Louzada and Martinez Steele24).

Adolescents are a particularly vulnerable group to this shifting food system, since they form lifelong eating patterns that are relevant to their own health and to the next generations(Reference Chen, Huang and Lo25,Reference Birkhead, Riser and Mesler26) . They experience a range of different social meal settings, such as school and home, throughout the day and share their meals with different people under these settings. The food provision for adolescents is likely to be diverse in different locations, and consumption may vary depending on the other people present at eating occasions(Reference Higgs and Thomas27). Moreover, external influences, such as television (TV) and other behaviours (e.g. eating at the table during meals), may play a role on consumption patterns. Previous studies suggest that watching TV during meals was associated with increased ultraprocessed food consumption(Reference Martines, Machado and Neri28), whilst sharing meals with relatives may have encouraged the consumption of healthy food, such as fruits and vegetables(Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann29,Reference Jones30) . Therefore, assessing the link between various eating contexts and adolescents’ consumption patterns as well as identifying specific contexts that may encourage or discourage negative healthy eating behaviours is fundamental. Along these lines, we aimed to identify patterns of eating contexts at two meal occasions (lunch and dinner) and investigate the associations between these patterns and the consumption of ultraprocessed foods in a representative sample of UK adolescents.

Methods

Data source and collection

The study sample comprised 542 adolescents aged 11–18 years, who participated in the 2014–2016 National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS). The NDNS is a cross-sectional rolling survey that collects yearly information on all food and drinks consumed by a representative sample of the UK population. The sample was randomly drawn from households listed at the UK Postcode Addresses File. One adult and one child/adolescent were randomly selected from each household. A child ‘boost’ of addresses was included for scenarios where only children were recruited to ensure the participation of approximately equal numbers of children/adolescents and adults. Participants completed a 4-d food diary and were interviewed on their sociodemographic status. Details of the survey’s methodology have been previously published(31). NDNS was conducted according to guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the survey was approved by governance committees, respecting research ethics.

Participants received written instructions to record all foods and drinks consumed inside and outside their home over four consecutive days. Portion sizes were estimated based on either household measures or weights from packaging. Information on eating context (how the meal was consumed, with whom and where) was recorded for each eating occasion. Once completed, diaries were verified by interviewers together with respondents and missing details were added to enhance completeness. Visits were continuously carried out throughout each year to ensure that seasonal variations in dietary intake were captured. In addition, diary days were randomly selected to guarantee a balanced representation of all week days. All individuals who provided 3 or 4 d of dietary recordings were considered eligible for this study. Diaries were coded using Diet In Nutrients Out, whilst food and energy intake were estimated via a yearly updated nutrient composition data from the Department of Health’s Nutrient Databank(Reference Fitt, Cole and Ziauddeen32,Reference Finglas, Roe and Pinchen33) .

Context of eating at main meals

The eating context at meal occasions was examined separately for lunch and dinner throughout the 4 d of dietary assessment (four occasions for lunch and four occasions for dinner). The meal with highest energetic intake between 11.00 and 15.00 hours was defined as ‘lunch’ and the meal between 18.00 and 21.00 hours as ‘dinner’(Reference Leech, Worsley and Timperio34).

The eating context was assessed considering the location of the meal occasion, the individuals present, whether the TV was on and if the food was consumed at a table, based on data records of ‘How’ the meal was consumed, ‘With whom’ and ‘Where’ for every meal occasion. The category ‘How’ was recorded as ‘TV on’ and/or ‘At a table’ during each meal occasion. The category ‘With whom’ was evaluated for ‘Alone’, ‘With family/relatives’ and ‘With friends’, and the category ‘Where’ was evaluated for ‘At home, except bedroom’, ‘At home, bedroom’, ‘Friend’s or relative’s house’, ‘At school’, ‘Food outlets (coffee shop, deli, sandwich bar, restaurant, pub and fast food)’, ‘Leisure places (leisure activities, shopping, cinema and sports club)’ and ‘On the go (bus, car, train, street)’.

For each variable, we considered ‘no’ when the behaviour related to each eating context at lunch/dinner was not reported on the food diaries and ‘yes’ when the behaviour was reported on at least one of the 4 d.

Food classification according to processing

All foods included in food diaries were classified into one of the four NOVA food groups, which are defined through a classification system based on the extent and purpose of the industrial food processing(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy35). The first group includes the unprocessed or minimally processed foods, which are fresh or processed without adding substances to the original food (e.g. beans, rice, fresh or frozen meats, and milk). The second group refers to the processed culinary ingredients, which are substances obtained directly from group 1 foods or from nature and used to prepare/cook group 1 foods (e.g. vegetable oils, butter and table sugar). The third group comprises the processed foods, to which certain substances, such as salt, sugars and/or oils, have been added to group 1 foods (e.g. vegetables in brine, cheeses and breads made from flour, water and salt). The fourth group refers to the ultraprocessed foods, which are industrial formulations of many ingredients, several of exclusive industrial use, that are resulted from a sequence of physical and chemical processes applied to foods and their constituents (i.e. cookies, ice cream, candy, breakfast cereals, packaged snacks, soft drinks, sweetened fruit drinks, sweetened yogurts and dairy beverages, ready or semi-ready meals, sausages and other cured meats)(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Levy35). This study specifically assessed the consumption of ultraprocessed foods. Details on how food item classification was accomplished are explained in previously published papers(Reference Rauber, da Costa Louzada and Steele14,Reference Rauber, Louzada and Martinez Steele24) .

For each adolescent, the relative dietary contribution of ultraprocessed foods (% of total energy) was derived from all data available from food diaries.

Covariates

The covariates included were age in years, sex, ethnicity (white and non-white), region (England North, England Central/Midlands, England South (including London), Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and household occupational social (routine & manual occupations, intermediate occupations, lower managerial & professional occupations and higher managerial & professional occupations)(31).

Data analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was employed to identify the patterns of eating context through the application of a correlation matrix to the twelve components related to the eating context at meals. These components were expressed as binary variables (‘no’ and ‘yes’) and separately examined at lunch and dinner. We used the Principal Axis Factoring method (pcf option in Stata) to extract the factors since our data were not normally distributed(Reference Costello and Osborne36,Reference Schreiber37) . The number of retained factors was selected based on the scree plot assessment and a reasonable interpretation of the emerging factors(Reference Costello and Osborne38). Exploratory factor analysis assigns to each variable (in this case, each eating context) a factor load. The factor load indicates the magnitude of the correlation of each variable with that factor. The minimum loading of an item to be included in a factor was 0·30, and an orthogonal rotation was used to simplify the data structure(Reference Costello and Osborne38). The proportion of the variance explained by the factors retained is presented for each meal occasion (lunch and dinner). Sample adequacy was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) criteria, which assume values between 0 and 1, but values below 0·5 are considered unacceptable. In the present study, we obtained a KMO > 0·5 (0·60 for lunch and 0·58 for dinner).

Pattern scores were predicted for each individual sample and categorised into tertiles to express low (first tertile), middle (second tertile) and high (third tertile) adherence to the eating context pattern. The average score of each eating context pattern in the population was described according to sociodemographic characteristics, such as age group, sex, ethnicity, region and household occupational social. Linear regression was used to compare the average score of each pattern according to the sociodemographic characteristics.

For each survey day, we defined outliers of total dietary energy intake as values above the 99th or below the 1st percentile(Reference Nielsen and Adair39). Although some diaries were excluded as outliers based on the aforementioned criteria, no adolescents had all four diaries (one per day) excluded after this data treatment and 98 % completed the four food diary days.

Linear regression models adjusted for the covariates were used to test the association between the adherence to eating context patterns and the dietary share of ultraprocessed foods (% of total energy intake), using the low level (first tertile) as reference. Tests of linear trend were performed to examine the linear relationship of ordinal exposures, with more than two categories, and the outcomes. A statistical significance level of 5 % was assumed for all analyses.

Survey sample weights from the NDNS study were used in all analyses to account for sampling, proportions of observations from each UK region and non-response error. All statistical analyses were carried out using Stata Statistical Software version 14 (StataCorp).

Results

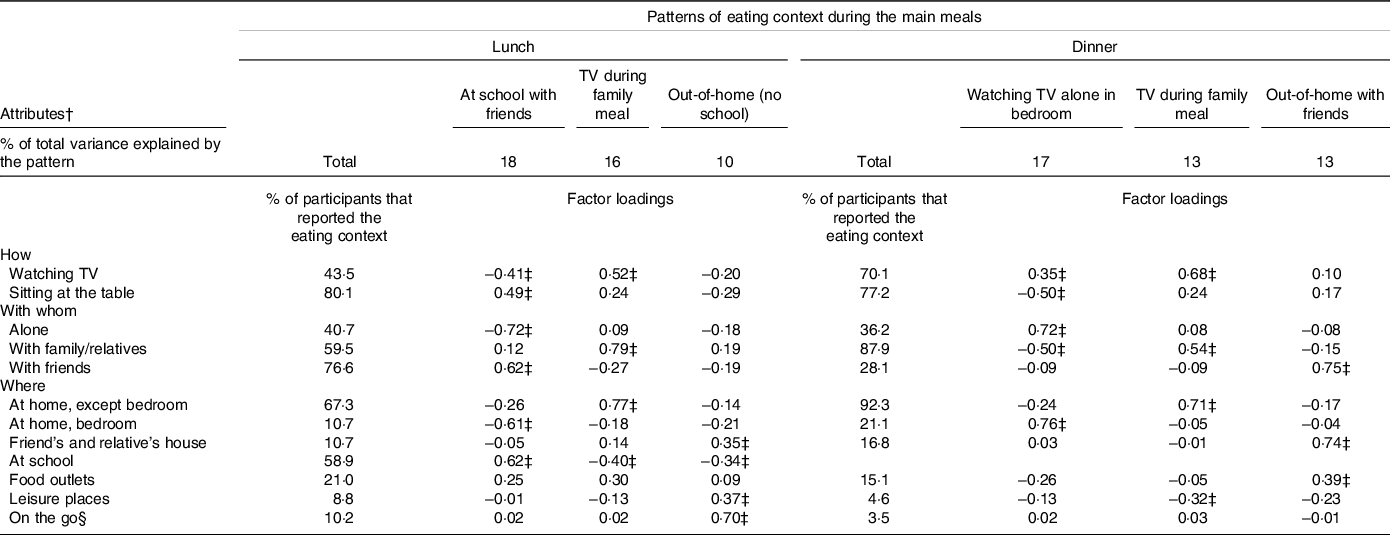

Table 1 shows the percentage of reported eating contexts by UK adolescents based on ‘How’ the main meal was consumed, ‘With whom’ and ‘Where’ as well as the attributes and factor loadings for each of the eating context patterns, identified at the two main meals. The vast majority of the adolescents reported ‘Sitting at the table’ during both lunch (80·1 %) and dinner (77·2 %). Eating ‘With friends’ was more frequent during lunch (76·6 %), while eating ‘With family/relatives’ was more common during dinner (87·9 %). More than 50 % of the adolescents reported eating ‘At home, except bedroom’ (67·3 %) and ‘At school’ (58·9 %) during lunch, and almost all (92·3 %) reported eating ‘At home, except bedroom’ during dinner.

Table 1. Percentage of reported eating context considering ‘How’ the main meal was consumed, ‘With whom’ and ‘Where’ and the patterns of eating context* during the main meals, identified by use of factor analysis among adolescents, UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS) (2014–2016) (Percentages)

TV, Television.

* Patterns obtained through exploratory factor analysis with factor loadings generated after rotation.

† The context of eating at meals was examined considering lunch and dinner during the four days of dietary assessment.

‡ The variable has loaded in the pattern.

§ Bus, car, train, street.

At lunch, three patterns were retained, explaining nearly 44 % of the variance. These were labelled aligned with the following factor loadings: ‘At school with friends’ – positive for having a meal at the table, with friends and at school, and negative for eating the meal whilst watching TV, alone and in the bedroom (at home); ‘TV during family meal’ – positive for eating the meal while watching TV, with family/relatives and at home, and negative for having a meal at school and ‘Out-of-home (no school)’ – positive for eating at a friend’s/relative’s house, leisure places or on the go, and negative for having a meal at school. At dinner, three different patterns were also retained, explaining nearly 43 % of the variance. The patterns were labelled considering the factor loadings as followed: ‘Watching TV alone in the bedroom’ – positive for eating the meal while watching TV, alone and in the bedroom (at home), and negative for having a meal at the table and with family/relatives; ‘TV during family meal’ – positive for eating the meal whilst watching TV, with family/relatives and at home, and negative for having a meal at leisure places and ‘Out-of-home with friends’ – positive for eating with friends and at food outlets.

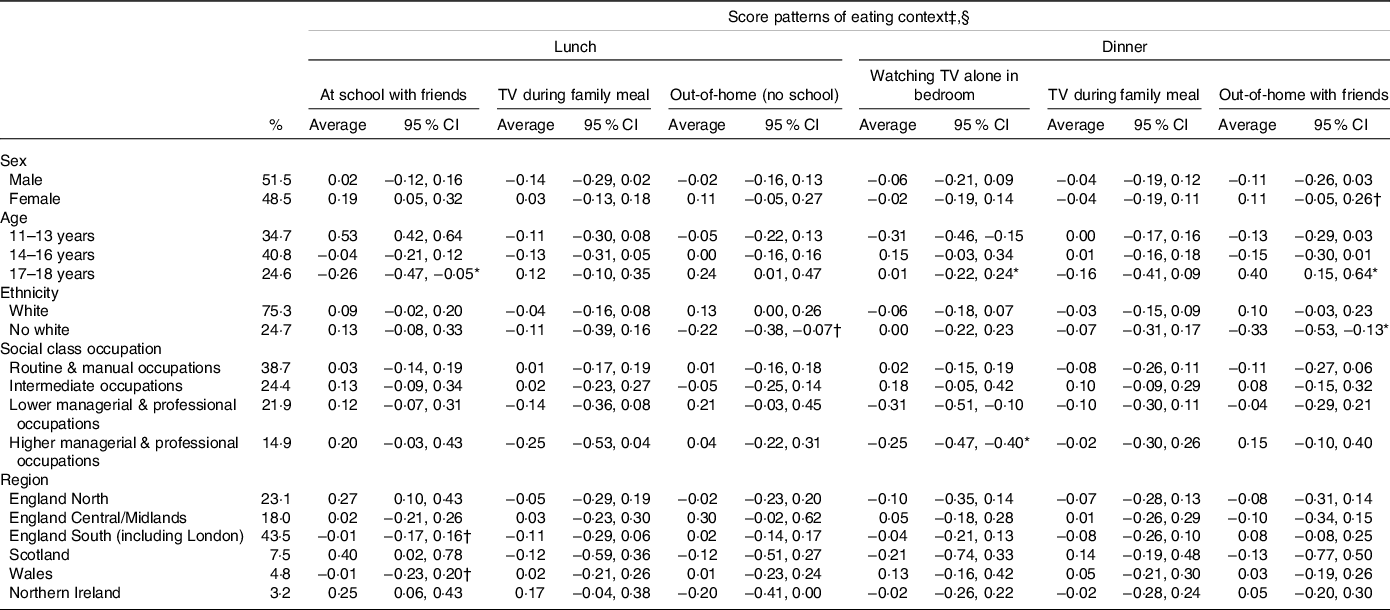

The average score of each eating context pattern according to characteristics of the UK adolescents is presented in Table 2. Higher score values indicate greater adherence to the pattern. At lunch, the average score predicted for the ‘At school with friends’ pattern decreased with age and was lower among those living in England South and Wales, while the score for the ‘Out-of-home (no school)’ pattern was greater among white people. At dinner, the average score for the ‘Watching TV alone in the bedroom’ pattern increased with age and lower level of household occupational social, while the score for the ‘Out-of-home with friends’ pattern was more elevated among girls and white British, increasing with age. The pattern ‘TV during family meal’ was not distinguished by any of the analysed sociodemographic characteristics of UK adolescents.

Table 2. Average score of each eating context pattern according to sociodemographic characteristics of adolescents, UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS) (2014–16)

(Percentages; average values and 95 % confidence intervals)

TV, Television.

* P for linear trend across categories

† P < 0·05 using the first category of each variable as the reference category.

‡ Patterns obtained through exploratory factor analysis with factor loadings generated after rotation.

§ Linear regression analyses comparing the average score of each pattern according to the sociodemographic characteristics.

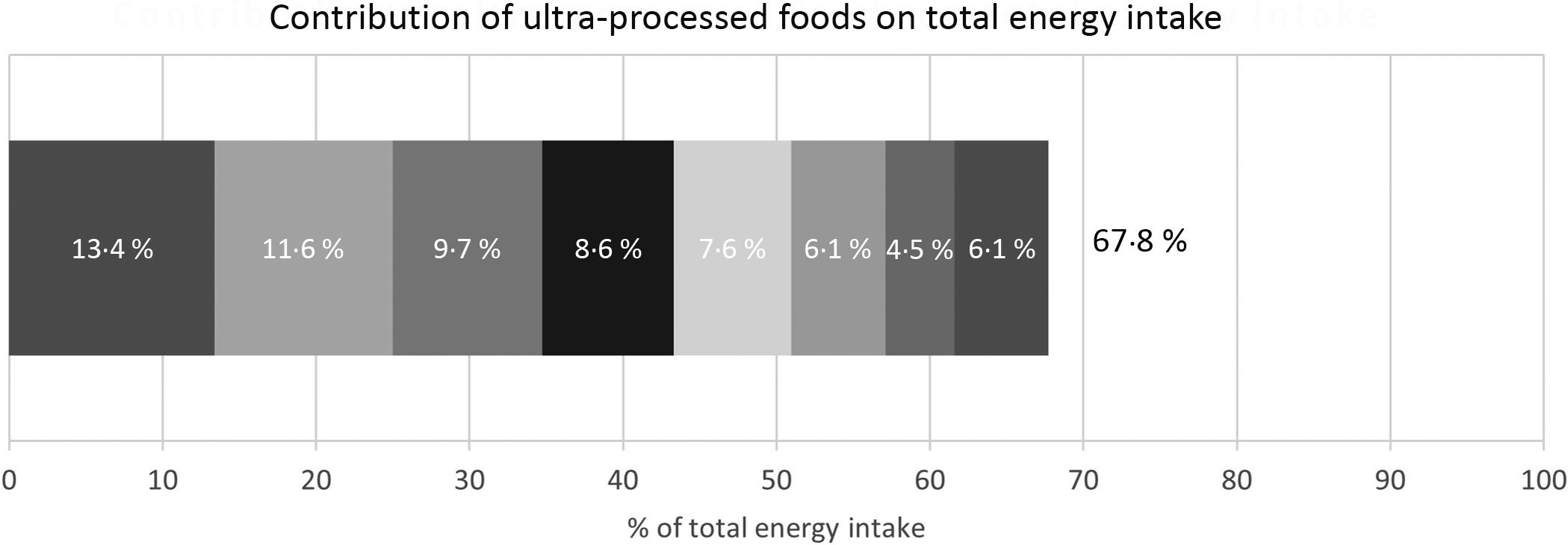

Ultraprocessed foods accounted for 67·8 % of total energy intake of UK adolescents. The main food groups contributing to ultraprocessed food consumption were packaged pre-prepared meals (13·4 % of total energy intake), packaged breads (11·6 %), sweets (9·7 %) and industrial French fries and pizza (8·6 %) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Contribution of ultraprocessed foods on the total energy consumed by adolescents, UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS) (2014–2016). ![]() , Pre-prepared meals;

, Pre-prepared meals; ![]() , packaged breads;

, packaged breads; ![]() , sweets;

, sweets; ![]() , French fries and pizza;

, French fries and pizza; ![]() , biscuits and snacks;

, biscuits and snacks; ![]() , beverages;

, beverages; ![]() , breakfast cereals;

, breakfast cereals; ![]() , spreads, sauces and others.

, spreads, sauces and others.

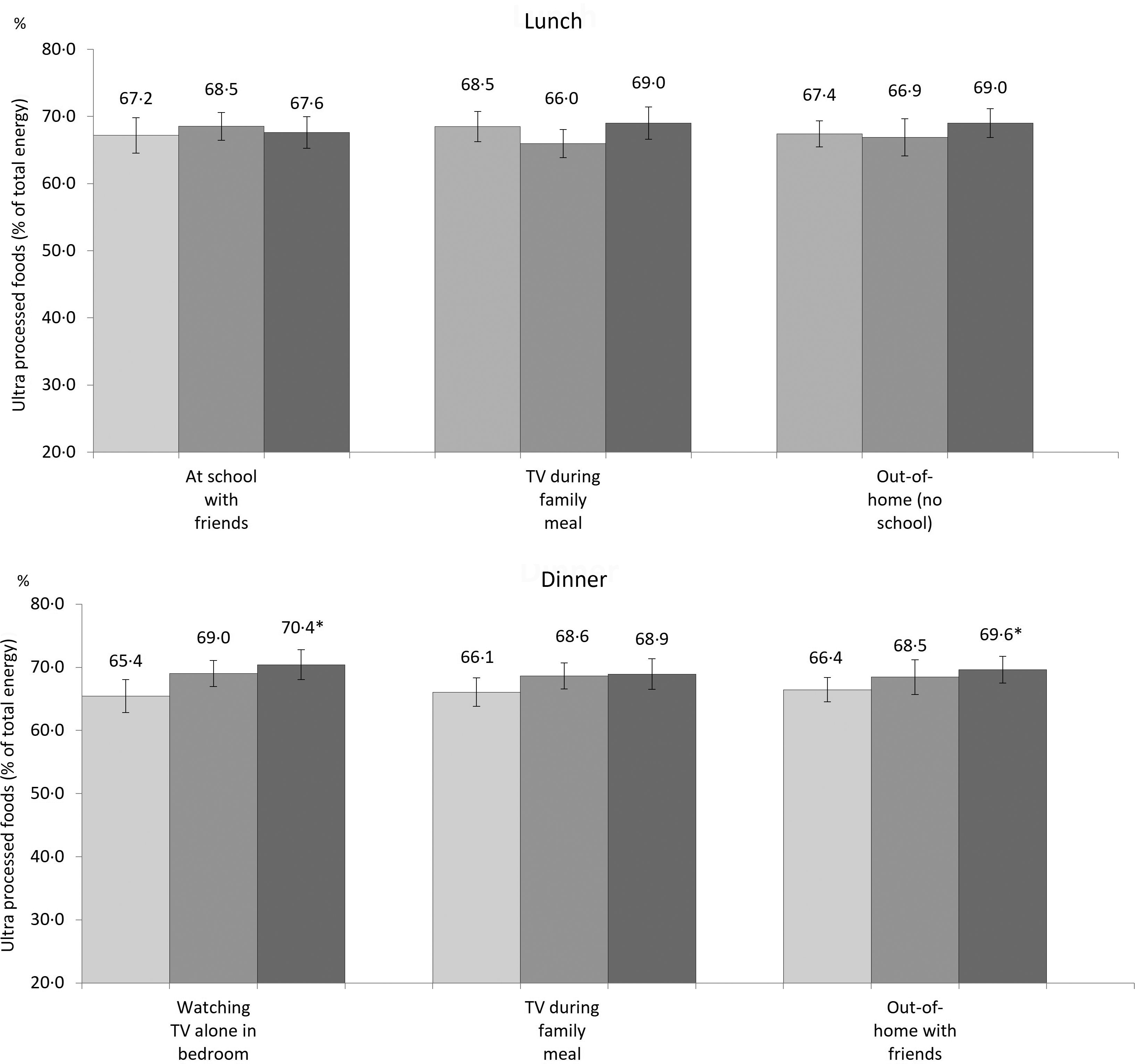

Fig. 2 shows the average consumption of ultraprocessed foods (% of total energy intake) according to the tertiles of adhesion to each eating context pattern (the first tertile indicates low adherence, and the third one indicates the high adherence to the pattern), while Table 3 presents the coefficients of association between the variables. At lunch, no difference in the consumption of ultraprocessed foods was observed for the patterns ‘At school with friends’, ‘TV during family meal’ and ‘Out-of-home (no school)’. On the other hand, the energy from ultraprocessed foods increased at dinner from 65·4 % in the first tertile to 70·4 % in the third tertile of the pattern ‘Watching TV alone in the bedroom’. The greater adherence to this pattern was associated with 4·95 % (95 % CI 1·87, 8·03) more energy intake from ultraprocessed foods in comparison with the adolescents who least adhere to this pattern. Regarding the pattern ‘Out-of-home with friends’, the energy acquired from ultraprocessed foods increased from 66·4 % in the first tertile to 69·6 % in the third tertile. The greater adherence to this pattern was associated with the acquirement of 3·17 % (95 % CI 0·21, 6·14) more energy from ultraprocessed foods, compared with adolescents who least adhere to this pattern. A significant linear trend was observed for the association between the tertiles of both eating context patterns and ultraprocessed food consumption (P-trend < 0·001). Although the consumption of ultraprocessed foods also increased with greater adherence to the ‘TV during family meal’ pattern (from 66·1 % in the first tertile to 68·9 % in the third tertile), no statistical significance was detected.

Fig. 2. Ultraprocessed food consumption according to the adherence of eating context patterns in adolescents, UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS) (2014–2016). Mean adjusted for sex, age (years), ethnicity (white and no white), region (England North, England Central/Midlands, England South, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and household occupational social (Routine & manual occupations, Intermediate occupations, Lower managerial & professional occupations and Higher managerial & professional occupations). * P < 0·05. ![]() , Low adherence;

, Low adherence; ![]() , medium adherence;

, medium adherence; ![]() , high adherence.

, high adherence.

Table 3. Association between ultraprocessed foods and the adherence to eating context patterns* among adolescents, UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme (NDNS) (2014–16)

(Coefficient and 95 % confidence intervals)

TV, Television.

* Patterns obtained through exploratory factor analysis with factor loadings generated after rotation.

† Based on the factor score tertiles, where the first tertile indicated low adherence and the third one showed high adherence to the pattern.

‡ P for linear trend across the tertile of patterns.

§ Linear regression adjusted for sex, age (years), ethnicity (white and no white), region (England North, England Central/Midlands, England South, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and household occupational social (Routine & manual occupations, Intermediate occupations, Lower managerial & professional occupations and Higher managerial & professional occupations).

Discussion

In this study covering representative data from the UK, we identified eating patterns at the main meals characterised by different elements, such as ‘how’ the meal was consumed, ‘with whom’ and ‘where’. The adherence to the patterns varied across sociodemographic characteristics such as age, region, ethnicity, sex and social class occupation, and a greater adherence to the patterns ‘Watching TV alone in bedroom’ and ‘Out-of-home with friends’ at dinner was associated with higher consumption of ultraprocessed foods on the diet of British adolescents.

When analysing eating contexts, it is worth considering that these circumstances usually take place in social contexts, respecting their specific norms and cultures(Reference Fischler2,Reference Yates and Warde4,Reference Higgs and Thomas27) . In the UK, the evening meal is the main daily meal in terms of social occasion (more frequently eaten with family) and meal content (more substantial dishes), while the lunch comprises quick and small dishes, for example, sandwiches(Reference Yates and Warde4,Reference Yates and Warde40) . Dinner is the moment when several household members are able to eat together(Reference Brannen, O’Connell and Mooney41,Reference Southerton42) . In general, these meals last longer, underlining their greater social importance, and, consequently, their influence on eating context(Reference Yates and Warde4). This could justify why only the eating context patterns at dinner were the ones associated with overall consumption of ultraprocessed foods.

Eating meals alone in the bedroom, while watching TV, was associated with a more elevated daily consumption of ultraprocessed foods. Watching TV while eating may cause a distraction, resulting in a delay in normal mealtime satiation and a reduction of internal satiety signals(Reference Braude and Stevenson43–Reference Bellissimo, Pencharz and Thomas45), which may lead to overconsumption. While watching TV, adolescents are also exposed to a larger number of advertisements, which are often promoting ultraprocessed foods(Reference Fagerberg, Langlet and Oravsky46,Reference Signal, Stanley and Smith47) . Even a brief exposure to advertising may be sufficient for adolescents to select the advertised food, however, the constant repetition of advertisements may reinforce such desire(Reference Borzekowski and Robinson48,Reference Buijzen, Schuurman and Bomhof49) . Furthermore, eating alone in the bedroom replaces the meals at the family table, hampering the sociability, which can be considered one of the meal components. On the other hand, by choosing to eat alone in the bedroom, adolescents are, in fact, opting for individualisation of eating(Reference Fischler2), which may result in more disadvantages than benefits. Family meal frequency is important in establishing positive eating behaviours, such as the consumption of fresh foods, and is more likely to occur around the table(Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann29,Reference Jones30,Reference Videon and Manning50–Reference Larson, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan52) . When children and adolescents are in the presence of their parents, they tend to consume less unhealthy foods(Reference Salvy, Elmo and Nitecki53). Thus, the context provided during family meals represents an important opportunity to expose healthful food choices to teenagers, assisting on parental modelling of eating behaviours(Reference Watts, Barr and Hanning54).

Families and friends play an important role on adolescents’ eating behaviours. However, for adolescents, foods consumed during family meals are different from those shared among friends(Reference Guidetti, Cavazza and Graziani55). We found that eating with friends in food outlets or friend’s houses was associated with higher daily consumption of ultraprocessed foods. Although shared meals are an important time for individuals to interact with friends, other factors can also influence on eating habits. To fit in social norms and be accepted in a group, it is common to adjust individual eating behaviours according to the social group and the perceived norms(Reference Fischler2,Reference Yates and Warde4,Reference Higgs and Thomas27) . Eating with friends may trigger a social facilitation effect on eating(Reference Ruddock, Brunstrom and Vartanian56), which might stand out for particular food types, such as highly palatable and high-energy snacks, especially among adolescents. A previous study reported that energy intake increased by 18 % when eating with friends, and a selective effect of social facilitation for the consumption of sweets and high-fat foods was observed(Reference Hetherington, Anderson and Norton57). Moreover, the eating location can play a stronger role in eating behaviour. Eating out-of-home, particularly in food outlets, was also linked to higher energy intakes from non-core foods (discretionary foods) among British adolescents(Reference Ziauddeen, Page and Penney58,Reference Toumpakari, Tilling and Haase59) .

Eating meals with family while watching TV was not associated with total ultraprocessed food consumption, corroborating the outcomes from a previous study conducted with UK children(Reference Onita, Azeredo and Jaime60). Different eating contexts associated with this pattern have shown opposite effects on eating behaviour, representing a possible explanation for this finding. While family meals have been associated with healthier dietary quality(Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann29,Reference Watts, Barr and Hanning54) , watching TV during meals has been associated with unhealthy food consumption(Reference Martines, Machado and Neri28,Reference Avery, Anderson and McCullough61) and a lower overall dietary quality score(Reference Trofholz, Tate and Miner62). Thus, family meals could be confounded by the influence of having the TV on during meals. Notwithstanding, we hypothesise that the apparent benefits of having a family meal(Reference Scagliusi, da Rocha Pereira and Unsain63–Reference Martins, Ricardo and Machado65) may be outweighed by the negative effects of having the TV on during meals(Reference Avery, Anderson and McCullough61,Reference FitzPatrick, Edmunds and Dennison66) . At dinner, we observed that the daily consumption of ultraprocessed foods increased with the greater adherence to the latter pattern. The absence of a statistical significance may be due to the reduced statistical power resulted from the categorisation of a continuous exposure variable(Reference Altman and Royston67).

Having meals at the table with friends at school was not associated with the consumption of total ultraprocessed food among adolescents. A previous study conducted with children and adolescents from the UK found that the percentage of energy intake from non-core foods at school increased with age, suggesting that the foods consumed at school are more protective for younger children than for older students(Reference Ziauddeen, Page and Penney58). As children age, their independence and freedom of choice augment, a phenomenon facilitated by the school structure that provides more flexible meal services(Reference Nelson, Bradbury and Poulter68,Reference Nelson, Nicholas and Suleiman69) , as well as by the possibility of purchasing and selecting foods outside the school(Reference Patterson, Risby and Chan70,Reference Briefel, Wilson and Gleason71) . Nevertheless, this is a speculation since, in this study, the content of the lunches was not assessed at students’ home, school or ‘out’ at local food outlets.

We identified that while older adolescents from low socio-economic status were more vulnerable to the pattern ‘Watching TV alone in the bedroom’, older adolescents, white and girls were more vulnerable to engage in the pattern ‘Out-of-home with friends’. The identification of these characteristics could assist the development of targeted interventions to reduce adolescents’ engagement in eating contexts associated with higher ultraprocessed food consumption.

Our analysis is novel since no other studies had tested the combined effects of the eating contexts (physical and social) on ultraprocessed food consumption of adolescents. In addition, we used data from the NDNS, a national UK survey, which is considered representative with high quality and contains up-to-date information on eating behaviour of UK population. The NOVA system use is another key strength of this study as it classifies foods by their level of processing through standardised and objective criteria.

Despite these strengths, the following potential limitations should be underlined. Although self-reporting dietary intake by adolescents is a commonly used method in other studies, this could lead to misreporting. Therefore, a degree of reactivity to food recordkeeping(Reference Subar, Freedman and Tooze72) and other dietary misreporting cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, multiple food diaries offer a more accurate dietary assessment method in comparison with a FFQ or a single 24-h recall(Reference Thompson and Subar73). Although NDNS data were obtained through methods optimised for collecting dietary intake(74), which minimised the neglected information, a previous report shows that intake underreport is an issue in this data set(Reference Murakami, McCaffrey and Livingstone75). We assessed and excluded implausible reporting from the analyses(Reference Nielsen and Adair39), but due to the lack of physical activity data for individuals under 16 years in the survey, we were not able to correctly estimate the energy requirements and exclude misreporters from our analyses. We have no theoretical reason to believe that adolescents who underreport their intake would misreport their eating context. Thus, the intake underreport constitutes a non-differential misclassification, which could have attenuated the associations found. In addition, the eating location was defined as the place of consumption, but information on the place of purchase would be advantageous to identify different eating contexts that are potentially associated with ultraprocessed food consumption. Moreover, we have performed multiple analyses without adjustments for potential inflated type I error(Reference Bland and Altman76). However, this study has a well-defined a priori hypothesis and biological plausibility for the explored associations, which stand out as strong epidemiological bases for not recommending multiple comparison adjustments(Reference Rothman77–Reference Perneger80). Finally, the determination of causality between the eating context effects and ultraprocessed food consumption was not feasible due to the cross-sectional design of the NDNS survey.

Although the differences in ultraprocessed food consumption are small, they reflect daily basis behaviours and are, therefore, meaningful. This is even more relevant when considering that the increase in ultraprocessed food consumption is strictly intertwined to the deterioration of overall dietary nutritional quality(Reference Moubarac, Batal and Louzada12–Reference Martínez Steele, Popkin and Swinburn16) and negative health outcomes(Reference Canhada, Luft and Giatti17–Reference Rico-Campà, Martínez-González and Alvarez-Alvarez23). However, we acknowledge that British adolescents presented an elevated consumption of ultraprocessed foods in all immediate eating contexts. Therefore, broader determinants of ultraprocessed food consumption should be targeted by Public Policies, and the eating context should be considered when planning interventions to target adolescent’s food consumption.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that adolescents, who followed the patterns of eating meals alone in the bedroom while watching TV and eating out with friends, consumed more ultraprocessed foods. Furthermore, dinner was more strongly related to this association than lunch. These findings suggest a potential relationship between the eating contexts and ultraprocessed food consumption by adolescents, particularly across different meal locations and social contexts. Therefore, policy and educational actions are needed at both individual and population levels to create and promote positive social eating environments, providing healthier food choices for adolescents. Likewise, further research should take eating context into consideration when planning interventions to target adolescents’ food consumption.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo - FAPESP for the financial support (F.R., grant number 2016/14302-7). FAPESP had no role in designing, analysing or writing this manuscript.

F. R. and R. B. L. conceived the idea for the analysis. All authors contributed to methods development. F. R. performed the analyses. All authors contributed to data interpretation. F. R. drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical comments on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.