1. Introduction

‘Prophecy consists in the inspired communication of divine attitudes to the prophetic consciousness’, writes Abraham Heschel, and ‘the divine pathos is the ground-tone of all these attitudes’. God's passionate concern for the world means that ‘human actions arouse in Him joy or sorrow, pleasure or wrath’, but this wrath always acts in service to divine mercy in a relation that defies the God of the philosophers.Footnote 1 For Israel's prophets, ‘[a]nger and mercy are not opposites but correlatives’.Footnote 2

Very few have followed Heschel to explore the intersection of wrath and mercy in the New Testament, as God's wrath is understandably an ‘ungeliebte’ topic of study.Footnote 3 This lacuna, however, often houses the Marcionite premise that wrath and mercy are mutually exclusive.Footnote 4 This problem is particularly acute in the study of Romans, in which Paul famously opens the body of the letter with the wrath of God (1.18).Footnote 5 Paul cites ὀργή twelve times in Romans, but scholars continue to puzzle over the relationship between this wrath and pronouncements of cosmic salvation in Christ. This tension often breaks on the exegesis of Rom 9–11, maybe the most controverted passage in Paul's corpus.Footnote 6 He divides his kindred into vessels of wrath and vessels of mercy, only to claim later that all Israel will be saved. Most find Paul's argument to be at best a tortuous dialectical detour, if not contradictory fantasy.

While many commentators allow that judgement somehow moves to mercy in the Israel-Kapitel, a proper conception of God's wrath is critical for tracing Paul's logic and making a coherent case. With his own scriptural reasoning, Paul considers that divine wrath is often provisional, and Rom 9–11 describes restorative wrath on Israel that leads to mercy on those judged. After addressing the decline of modern scholarly interest in divine wrath and canvassing images of judgement in Paul's scriptures, this article will demonstrate that Israel's plight in Rom 9–11 can only be understood through an appropriately thick lens of divine wrath.

2. The Disappearance of Wrath

Daniel Walker wrote in 1964 of a ‘decline of hell’ in theological teaching beginning in the seventeenth century,Footnote 7 and there has been a corresponding decline in the study of wrath in Paul. Friedrich Schleiermacher was foundational in this modern dismissal, denying that wrath or retributive punishment exists in God's justiceFootnote 8 and asserting that the doctrine of God's wrath is neither grounded in Christianity nor even ‘a proper doctrine’.Footnote 9 A certain historicism drives Schleiermacher's belief: ‘now is the time to summon humanity’ against the ‘false fear of God's wrath’.Footnote 10 Paul only references God's wrath as an accommodation to his Jewish audience, who still held elementary, Old Testament notions of God as an angry deity.Footnote 11 Adolf von Harnack famously avers that ‘Marcion was the only Gentile Christian who understood Paul, and even he misunderstood him’,Footnote 12 going so far as to support the rejection of the Old Testament in nineteenth-century Christianity.Footnote 13 Part of Harnack's justification for decanonising the Jewish scriptures seems to have stemmed from the putative antithesis between judgement and mercy: ‘Marcion proclaimed with a splendid assurance that the loving will of Jesus (and, that is, of God) does not judge, but comes to our aid.’Footnote 14 In his 1932 Romans commentary, C. H. Dodd contends that Paul ‘retains the concept of the “the Wrath of God” … to describe an inevitable process of cause and effect in a moral universe’.Footnote 15 The picture of Rom 1.18–32 describes a ‘natural process of cause and effect, and not … the direct act of God’,Footnote 16 while the wrath in 12.19 ‘means the principle of retribution inherent in a moral universe’.Footnote 17 Hence, anticipated by Schleiermacher and followed by others,Footnote 18 Dodd sees no real wrath in Paul's God.

The decades since Stendahl and SandersFootnote 19 have witnessed many studies of judgement in Paul, but these primarily focus on the mechanism of justification in light of a new perspective on Judaism, or on the puzzle of fitting salvation by grace together with passages implying judgement by works.Footnote 20 There is little treatment of the character of God's wrath in relation to mercy, and the relation is often viewed as a simple opposition. Even someone as starkly opposed to Marcion's programme as Richard Hays can pit ‘severe retributive justice’ against ‘God's gracious saving power’, the latter constituting righteousness in Rom 3.21.Footnote 21 In Rom 9–11, ‘[o]nly the presence of the seed distinguishes Israel from the archetypal targets of God's wrath’.Footnote 22 Interpreters in the ‘apocalyptic Paul’ camp often speak of God's judgement, but they rarely probe God's wrath on human beings.Footnote 23 More typical is reflection on God's judgement of Sin, Death or the world. For instance, Martinus de Boer concludes that for Paul ‘[t]he final judgment entails God's defeat and destruction of cosmic evil forces’.Footnote 24 Douglas Campbell insists that ‘there is no retributive character’ at all in Paul's theology of God.Footnote 25 Paul's Gospel ‘speaks of a fundamentally saving and benevolent God’; the ὀργὴ θεοῦ in Rom 1.18 lies at the centre of the Teacher's gospel (not Paul's), and ‘responds to all actions retributively, and to sinful actions punitively’. These pictures ‘could not, in this sense, be more different. And only one is thoroughly rooted in the implications of the Christ event’.Footnote 26 Taking cues from Rom 5, Susan Eastman emphasises God's condemnation of the Sin that Christ absorbs in his participation in human flesh and death.Footnote 27 The liberative pictures in Rom 5 and 8 apparently overshadow the judgement on humanity depicted in Rom 1.18–3.20.Footnote 28

John Barclay has done much to correct the notion that grace cannot involve punishment,Footnote 29 but neither he nor his protégés in the Durham ‘grace’ schoolFootnote 30 have yet probed what wrath is for Paul in Romans and how it might co-exist with mercy. In her review of Barclay's groundbreaking work on grace, Susan Eastman calls for a corresponding re-examination of judgement in Paul.Footnote 31

In recent study on Paul, God's wrath sometimes appears on the periphery, but it has not been the centre of sustained examination. For many it seems that God's mercy cannot co-exist with wrath, and Paul is inconsistent when he speaks of both, as in Rom 9–11.Footnote 32 This is precisely the putative inconsistency that the current article contests, and images of divine wrath in Paul's own scriptures shed clarifying light on the problem.

3. The Scriptural Background of God's Wrath in Romans

Paul's initial, driving image for God's wrath as handing people over (Rom 1.24, 26, 28) would have rung true to Jewish ears familiar with Israel's traditions. God delivers the disobedient (often Israel) to enemies repeatedly in the Jewish literature circulating in Paul's time, most especially in that which he considered scripture. The relevant examples are too many to enumerate here, so a few will suffice. In Lev 26.25Footnote 33 God will avenge his covenant by sending death and handing over (παραδίδωμι) transgressors into enemy hands. At the beginning of Judges, ‘the Lord was very angry with Israel and gave them over [παραδίδωμι] into the hands of the plunderers’ (Judg 2.14).Footnote 34 God's wrath in Isa 34.2 leads him to hand people over (παραδίδωμι) to slaughter. Psalm 105.40–1 (106 MT) reads: ‘The Lord was angered in wrath and … delivered his people [παραδίδωμι] into the hands of their enemies’. In 2 Chr 6.36, Solomon says of God: ‘If they sin against you (for there is no one who does not sin) and you strike them [MT “are angry”] and hand them over [παραδίδωμι] before the enemies …’Footnote 35

There is another facet of God's wrath in Romans, however, that also reflects Paul's scriptures: namely, that wrath is often temporary and directed towards mercy. As noted above, Heschel has persuasively demonstrated how prevalent this notion is in the prophetic literature (and beyond), arguing that restorative wrath is central to the divine pathos that lies at the heart of prophetic theology.Footnote 36 God's wrath is not divorced from mercy but serves it as a provisional measure: ‘Anger and mercy are not opposites but correlatives.’Footnote 37 This feature of wrath may not be quite as ubiquitous as Heschel claims, in the prophets or elsewhere, but across the scriptures wrath can be temporary and even remedial, and this is often expressed with ‘chastening’ language.Footnote 38

Again, only a few examples of temporary and/or remedial wrath must suffice, but the theme pervades the Old Testament. Restorative punishment is especially prominent in the most cited book in Romans, Isaiah.Footnote 39 After describing the death and destruction God sends upon Israel in anger, Isaiah claims that the people did not turn to seek the Lord until they were struck (9.7–12). With the refrain that ‘his anger has not been diverted’ (see 9.11) and threats of wrath both through and against Assyria, Isa 10.4–6 introduces a confusing string of judgementsFootnote 40 that will whittle Israel down to a remnant (vv. 22–3, cited in Rom 9.27–8), sending dishonour upon Israel'sFootnote 41 honour and glory (v. 16; cf. Rom 9.21–3). These woes are characterised as sanctifying punishment: ‘The light of Israel will be a fire and will sanctify him in burning fire’ (Isa 10.17; cf. 1.25; 4.3–4). In the summative doxology of Isa 12, God promises, ‘you will say in that day, “I will bless you, Lord, because you were angry with me and you turned away your anger and had mercy on me”’ (vv. 1–2). God shockingly speaks of ‘striking and healing’ Egyptians in Isa 19, drawing them to return to God and receive mercy. As God judges the labourers of Ephraim in Isa 28, he will lay a trustworthy cornerstone (v. 16, cited in Rom 9.33), so that judgement will be for hope (28.17), and despite the wrath that will come (v. 21), ‘you will be chastened [παιδευθήσῃ] by your God's judgement, and you shall rejoice’ (v. 26). These images all occur before the famous turn from judgement to mercy beginning in Isa 40, after which temporary and remedial judgement continue to abound: for example, ‘On account of my wrath I struck you and on account of my mercy I loved you’ (60.10).Footnote 42

This pattern is by no means limited to Isaiah: God's wrath is depicted as temporary or chastening throughout the law, prophets and writings. Even Lamentations speaks of God's wrath ending and turning to steadfast love (cf. Lam 3.25–33; 4.22).Footnote 43 The Psalms, also cited frequently in Romans,Footnote 44 are especially full of these images, as the psalmists often consider themselves to be under divine wrath that can be temporary (e.g. Pss 37; 73; 84; 105.40–8) or remedial (77.31–8; 82.15–19; 89.10–12; 93.10–12; 118.67, 71, 75). One of the most common forms of judgement in the psalter is rejection (usually ἀπωθέω, a critical term for judgement in Rom 11), but there is a repeated conviction that rejection is temporary (e.g. 43.10, 24; 59.3; 73.12–23; 88.39–50). Similar provisional wrath also permeates Jewish literature outside of the MT canon.Footnote 45

Paul's scriptures repeatedly depict mercy and judgement as two arms of a complex divine love. These passages do not dictate Paul's own views, and some scriptural texts do not portray divine wrath as temporary or remedial. Nonetheless, this background does provide a plausibility structure within which one should not be surprised if Paul also describes divine wrath that leads to mercy. In fact, outside Romans Paul himself signals that God's judgement can serve chastening purposes,Footnote 46 even if it does not always do so.Footnote 47 Such provisional wrath also emerges across Romans and provides an interpretive key to Paul's controversial account of God and Israel in Rom 9–11.

4. Rom 9–11 as Microcosm of Rom 1–8

Before detailed exegesis, it will be helpful to recognise an overarching resonance between Paul's argument about God and Israel in Rom 9–11 and his argument about God and all humanity in Rom 1–8. Many scholars recognise links between Rom 1–8 and 9–11,Footnote 48 but none have appreciated the extent of this relation, which will prove vital for grasping Paul's logic in the latter. Closely comparing the two sections’ features reveals that Rom 9–11 functions as a microcosm of Rom 1–8. The end of Rom 8 leaves one wondering, in light of this cosmic salvation: what about Israel – specifically unbelieving Israel?Footnote 49 Romans 9–11 is Paul's answer. Here Paul applies to disobedientFootnote 50 Israel the trajectory of argument he has traced on the cosmic scale in chapters 1–8.Footnote 51

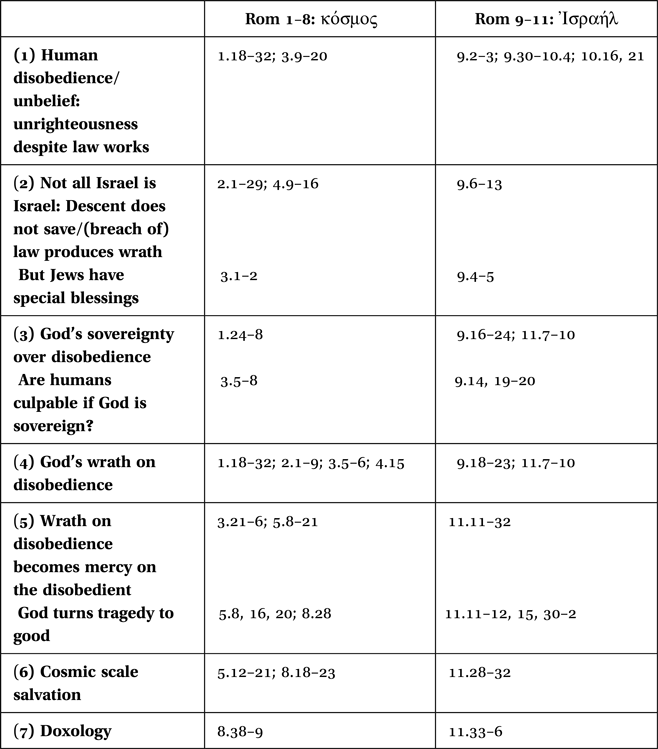

The major components of Paul's argument in both sections are set out in Table 1. These points clarify that God relates to disobedient Israel in Rom 9–11 in a fashion parallel with how he relates to disobedient humanity in Rom 1–8. Paul's line of argument is not always sequential, but the key points appear prominently in Rom 1–8 and 9–11:

Human disobedience/ → God's sovereignty → God's wrath → God's salvation

unbelief over disobedience on disobedience follows wrath

Table 1. Comparison of Argument in Rom 1–8 and Rom 9–11

For the present purposes, the key point to recognise about the divine wrath outlined in 1.18–3.20 is that for at least some it is temporary and leads to mercy. On the terms Paul has set,Footnote 52 3.20 demonstrates that everyone is unrighteous and therefore (1.18) under God's wrath, yet Paul does not imagine everyone remaining under wrath forever. At least some receive grace and salvation from wrath (5.9) through Christ, whom God ‘handed over (παρέδωκεν) for us all’ (8.32), meaning that the wrath introduced at 1.18 is temporary and consonant with mercy for some. When one allows this possibility for the judgement described in Rom 9–11, these chapters cohere and mirror Rom 1–8.

5. Wrath and Mercy in Rom 9–11

As is the case with Rom 1–8, so in Rom 9–11 a clear grasp of Paul's logic hinges on a proper conception of divine judgement. In light of texts such as 5.18 and the crescendo of 8.39, it may seem that God's wrath has vanished, since ‘nothing can separate us from the love of Christ’. But it turns out that 8.39 is not the finale, as Paul in Rom 9 seems to retract his cosmic picture of salvation in Christ and reintroduce some of the characters one thought had been killed off: unbelief, disobedience, exclusion, and then that dreaded word that began the body of the letter, wrath. What has happened?Footnote 53 In the microcosmic relation outlined above, Rom 9–11 is Paul's application of Rom 1–8 to Israel.

Just as Paul begins the letter by asserting God's judging wrath upon the world's unrighteousness (1.18), he begins chapters 9–11 by casting some Israelites as recipients of God's judgements, and not only with the phrase σκεύη ὀργῆς in 9.22.Footnote 54 Paul also signals this exclusion by saying it is not the case that ‘all Israel is Israel’ and by using language of exclusive election in Rom 9 (see especially vv. 6–8, 11–13, 15, 18, 21, 30–3). The division between God's mercy and judgement is concisely stated in 9.18: God has mercy on whom he pleases, and he hardens whom he pleases. The vessels made for dishonour and wrath rather than honour and mercy in 9.21–2 align with those whom God hardens in 9.18. The picture is bleak.Footnote 55

Furthermore, in Rom 11 Paul envisions God's active judgement even more vividly than in Rom 9. In 11.7 he claims that Israel did not reach what it sought – presumably righteousness or the law of righteousness from 9.31. Israel did not reach it, but the ‘elect’ or ‘election’ (ἐκλογή) did – presumably those within Israel who are of the election. The ‘rest’, Paul says in 11.7, were hardened. Then he clarifies that this is a divine passive (see v. 8), as God is the one who actively hardens the rest, i.e. the non-elect according to 11.7. God's judgement further entails giving them a spirit of stupor, eyes that do not see, ears that do not hear and darkened eyes, and placing a snare and a stumbling block in their way. This punishment by God in 11.7–10 describes God pouring out his wrath on some of Israel: the non-elect.

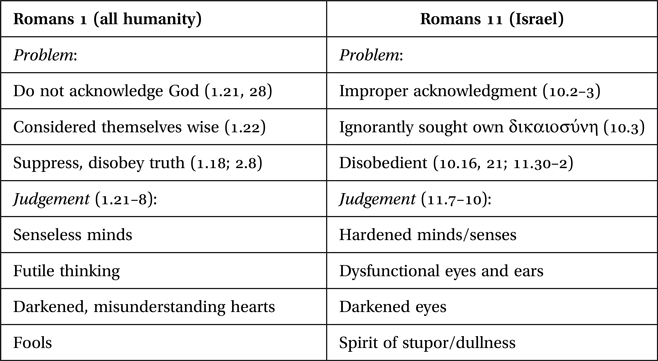

Why classify the actions in 11.7–10 as wrath? First, descriptions of divine wrath in Romans do not hinge on the use of the particular word ὀργή, as wrath, judgement and punishment are closely intertwined and often interchangeable in the letter. Amidst other ambiguities, every occurrence of ὀργή in Romans depicts some form of undesirable punishment falling upon human disobedience, none suggesting anyone other than God as the agent.Footnote 56 Furthermore, Paul often uses ὀργή and ‘judge’ terms synonymously to denote God's punitive actions (e.g. 2.2–5; 3.5–6; 13.2–5). Thus, wrath in Romans is judgement that involves punishment in a broad sense. A second reason to classify 11.7–10 as wrath is that in vv. 8–10 Paul cites texts which themselves clearly describe divine judgement: Ps 68 (vv. 23–4 are cited in Rom 11.9–10) even explicitly labels these actions as ὀργή (see 68.25). Third, Paul has already opposed hardening (σκληρύνω) to mercy in 9.18, just before he then opposes wrath to mercy in 9.22–3, forging a link between hardening and wrath. Here in 11.7 he applies a similar image of hardening to ‘the rest’. Fourth, the picture in 11.7–10 closely resembles Rom 1. People are culpable, but God emerges as the agent who turns people over – in Rom 1 to senseless minds, futile thinking and darkened hearts, and here in Rom 11 to hardening, dullness, blindness and deafness. Hence, both Rom 1 and Rom 11 portray God's judgement in terms of epistemic affliction.

This fourth point signals a pronounced resemblance between the portraits of divine judgement in Rom 1 and Rom 11 (Table 2). This is further confirmation that chapters 9–11 fit with chapters 1–8: Paul is applying the message of Rom 1–8 to Israel, and God's wrath takes similar shape when he hands people over to disobedience.

Table 2. Wrath in Romans 1 and Romans 11

Part of the message in Rom 1–8, however, is that God's wrath can lead to future mercy. Paul declares in 11.11 that, although God has made these Israelites stumble, this is not done to make them fall. Rather, this punishment is serving a purpose, since by their trespass salvation comes to the gentiles. Then Paul anticipates a further purpose for this gentile inclusion: namely, to make excluded Israel jealous. In the next verse (v. 12) Paul anticipates the full inclusion (πλήρωμα) of those who now trespass and have been defeated. In 11.15, he assumes that they have indeed been cast away (ἀποβολή), but envisions their acceptance. Thus, in these verses Paul makes clear that God's judgement of exclusion and casting away is not necessarily permanent and does not preclude future inclusion and salvation. In light of the common image of God's temporary wrath in Paul's scriptures, this should come as no surprise.

After warning the gentiles in his audience not to grow arrogant over these now excluded Jews (v. 18), Paul continues this line in 11.25, telling them that the mystery he is about to reveal should prevent them from being ‘wise to yourselves’. This mystery ties back to 11.7, when Paul spoke of the rest (non-elect) being hardened: here in 11.25 he continues to describe their plight in similar terms: ‘a partial hardening has come upon Israel until the fullness of the gentiles enters, and in this way all Israel will be saved’.

Many factors suggest that ‘all Israel’ refers to Israel κατὰ σάρκα (9.3), regardless of how καὶ οὕτως is read.Footnote 57 Much ink has been spilled on the question,Footnote 58 and the key points need not be rehashed. What is most germane for the current argument is that Paul has already and repeatedly insisted that God's judgement on those now excluded and hardened does not preclude future salvation (11.11–12, 15–16, 23–4), and this salvation comes from the same God who has hardened the ‘rest’.Footnote 59 Furthermore, the mystery is supposed to work against gentile pride (11.25). If the content of the mystery is simply that some Israelites have been hardened for ‘you gentiles’ to come in, this is precisely what Paul says in 11.19 is an example of misguided boasting: ‘You will say then, “Branches were broken off in order that I might be grafted in.”’ The mystery is that hardened Israel will follow gentiles through the door of salvation: wrath leads to mercy.Footnote 60

The mystery of hardening and wrath leading to salvation addresses the problem that Paul has been tackling since 9.1, namely, what is our supposedly faithful God from chapters 1–8 doing about his promises to Israel? To answer this, Paul admits that some of Israel are not Israel because they do not now believe, and God is sovereign even over this disobedience – just as God is the actor in 1.18–32. God has appointed some as vessels of wrath and some as vessels of mercy. Paul then describes how God works out this judgement on those who are not now in this election: God hardens them, blinds them and deafens them, very much like God's turning over people to darkened hearts and senseless minds in 1.21–2, 28. In 11.25–6, however, Paul asserts that this hardening upon part of Israel only lasts until the full inclusion of the gentiles, and this inclusion of gentiles will be the means by which all Israel is then saved.

One can now step back and see three things that confirm this reading. First, this trajectory resembles the arc of chapters 1–8. What Rom 1–8 describes on a cosmic scale, Rom 9–11 now applies to a specific case. In both cases this arc begins by looking at unbelief and disobedience, then it notes God's wrath at this disobedience, describes God's judging actions of giving people over to disobedient and senseless minds, and explains how those at odds with God and under God's wrath are brought back through God's salvation in all-encompassing language. Second, the pattern of God's wrath leading to God's mercy also resembles a common feature of God's judgement upon Israel in their own traditions: across Paul's scriptures as well as other Jewish literature, God's wrath can be temporary, consonant with mercy and even remedial. Third, this pattern is confirmed by the very last verse of Paul's argument in Rom 9–11 before the doxology: ‘God has imprisoned all in disobedience in order that he might have mercy upon all.’ Imprisoning in disobedience is what God does in 1.18–32 by turning people over, and this is precisely what God does to disobedient Israel in Rom 11, turning them over to hardening, blindness and deafness. In both cases, this turning over to disobedience is not the end, but rather leads to God's mercy upon all.

Most immediately, Rom 11.32 wraps up Paul's argument from vv. 30–1. ‘You gentiles’ were disobedient but have now received mercy by Israel's disobedience, and they have been disobedient but will also receive mercy. Disobedience by all moves towards mercy upon all. Furthermore, 11.32 concludes all of chapters 9–11 as well, by summarising the arc of God's punishment upon unbelief that then leads to mercy upon all, i.e. including currently hardened Israel. But 11.32 also culminates all of chapters 1–11. Not only is the trajectory of disobedience to mercy present in 11.30–1 or in chapters 9–11 where part of Israel is disobedient but then will receive mercy, but this is also the trajectory across Rom 1–11. The body of the letter begins with God's wrath upon disobedience, but this wrath is not the end of the story, and salvation comes. Then chapters 9–11 finalise the move from wrath to mercy by answering the pressing question that still prevents one from saying – even at the end of chapter 8 – that God has mercy upon all: ‘What about unbelieving Israel?’ These Israelites are needed to complete the all. Now that he has answered this question, Paul can stretch back out to the cosmic scale and declare at the end not just of 9–11 but also of 1–11, ‘God has imprisoned all in disobedience in order that he might have mercy upon all.’

6. Conclusion: Marrying Wrath and Mercy

The range of interpretations aimed at comprehending Paul's argument in Rom 9–11 is as widely disparate as anything in Pauline scholarship. Heikki Räisänen captures the nub of the problem for most: Paul's argument in 9.6–29 is logical and complete even if unsatisfying to some, viz. God's word has not failed because he never promised anything to ethnic Israel.Footnote 61 What follows 9.29, particularly in chapter 11, is what commentators struggle to square both with 9.6–29 and with chapters 1–8.

Some claim that Paul is being heavily dialectical,Footnote 62 but Räisänen retorts that ‘vage Behauptungen über Dialektik oder Paradoxie’ distract from legitimate attempts to interpret the discrepancy in these chapters.Footnote 63 Others believe that Paul changes his meaning for ‘Israel’ within one sentence, climactically revealing that ‘Israel’ refers to the body of believers rather than Israelites.Footnote 64 Several have contended that Paul speaks here of two different covenants, whereby gentiles are saved by faith while Israel has a Sonderweg that does not require this allegiance to Christ.Footnote 65 Some even suggest that Paul received a new revelation between Rom 9 and Rom 11.Footnote 66 Before most of these efforts, however, Rudolf Bultmann had already deemed Rom 11 a ‘speculative fantasy’ of Paul's in which he is driven to hold out hope for historical Israel.Footnote 67 Bultmann's conclusion, followed by many, is that Rom 9 and Rom 11 are completely contradictory.Footnote 68

One root of this dizzying array of readings is a common but misleading presupposition that wrath and mercy are mutually exclusive. On that basis, if Paul speaks of wrath and mercy on Israel, he must be contradicting himself, or dithering in dialectic, or speaking of two covenants or of two Israels. But when the presupposition is removed, the need for these strains collapses. The conviction that wrath and mercy are opposites can be traced through the history of interpretation back at least to Marcion, but Paul's scriptures frequently bear testimony to the contrary. Living in the thought-world of texts such as Isaiah and the Psalms, where so often ‘the secret of anger is God's care’,Footnote 69 Paul describes a remarkable but not contradictory relationship between God and his people. As with the cosmos, so with Israel: ‘On account of my wrath I struck you and on account of my mercy I loved you’ (Isa 60.10).