1 Introduction

In late 2010, St. Joseph’s Hospital of Phoenix, Arizona, lost its 116-year affiliation with the Catholic Church over its treatment of a young woman. The patient, a mother of four, was 11 weeks pregnant when she was admitted to the hospital with a severe medical condition. Her physicians determined that both she and the baby faced a nearly 100% risk of death if the pregnancy continued (USA Today, 2010b). Following consultations with the patient and her family, the doctors recommended an abortion to save the woman’s life. The hospital’s ethics committee, which included Sister Margaret McBride, a Catholic nun, approved the procedure. The woman lived (USA Today, 2010a).

In the aftermath of the decision, the hospital issued a statement saying that in the absence of an explicit Catholic directive instructing otherwise, it had an obligation to “make the most life-affirming decision” (The Arizona Republic, 2010). But when Reverend Thomas J. Olmsted, Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Phoenix, learned about the event, he declared it to be a direct and impermissible abortion and excommunicated Sister McBride. The tension between these positions appears to reflect different moral judgments. Whereas the hospital focused on the positive outcomes of the procedure and viewed the negative outcomes as unfortunate side effects (“the goal was not to end the pregnancy but save the mother’s life”, Huffington Post, 2010), the Bishop focused on the negative outcomes and dismissed the importance of benevolent intentions. He emphasized that “While medical professionals should certainly try to save a pregnant mother’s life, the means by which they do so can never be directly killing her unborn child. The end does not justify the means” (The Arizona Republic, 2010).

Religious individuals and organizations around the globe face similar moral conflicts between religiously-inspired rules and consequences. In two recent cases, female students in Saudi Arabia lost their lives in incidents that required decision-makers to choose between saving lives and chastity rules. In one case, religious police in Mecca prevented schoolgirls from exiting a burning school because they were not “covered properly”. In another case, an Islamic women-only university barred male paramedics from entering the campus to assist a female student who suffered a heart attack and later died. In both cases, other Muslims, including from within the organizations, criticized the decisions for placing one moral principle — chastity — over an arguably more important principle — saving lives.

In yet another recent example, Christian American non-profits argued in court that filing a notice of religious objection to contraceptive health coverage makes them complicit in the sin of providing contraceptives, because based on the notice the government arranges to provide the coverage to employees through the employer’s insurer. Little Sisters of the Poor and other religious organizations argued that filing the notice is therefore morally forbidden. Meanwhile, other petitioners that were not granted the option to file the notice — for example, the Evangelical owners of Hobby Lobby — requested to file the notice in order to solve the conflict between their beliefs and the law.

These cases raise a host of issues about moral judgment in general and the role of religion in particular. Research in moral psychology has found that religious decision-makers generally tend to form rule-based (deontological) judgments rather than outcome-based (utilitarian or consequentialist) judgments (more on that below). Still, religious decision-makers seem to have substantial disagreements over which moral rule to apply. This paper asks what may explain these differences and investigates several potential mechanisms. But first, we provide a brief summary of the literature on moral judgment and religion.

1.1 Utilitarianism, Deontology, and Religion

The research on moral judgment has focused on two central, competing approaches to morality: deontology and utilitarian consequentialism (Reference Cushman, Young and HauserCushman, 2013; Reference Bülow, Sprung, Reinhart, Prayag, Du and ArmaganidisGreene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley & Cohen, 2001; Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and KeysarKoenigs et al., 2007). From a utilitarian perspective, the sole criterion that determines the morality of an act is whether it brings about more good than harm on the whole (Mill, 1863; Bentham, 1789). From a deontological perspective, consequences are important but not determinative. Rather, morality is determined on the basis of the properties of action, and there are rules to distinguish permissible from impermissible actions. Some acts (e.g., stealing, lying, or killing) are considered inherently wrong and are generally impermissible even as a means of furthering good outcomes (Reference KantKant, 1785; Reference KohlbergKohlberg, 1969; Reference ZamirZamir, 2014). One classical dilemma that illustrates the competition between deontology and consequentialism is the “trolley problem”. Is it permissible to save five innocent people from a runaway trolley by killing one innocent person? This dilemma has long been perceived to capture the basic moral conflict between action-based and outcome-based judgment.

Recent studies that explored the relationship between moral judgment and religion suggest that monotheist religions generally promote deontological over consequentialist judgment. For example, Piazza and colleagues found that religious individuals are more likely to evaluate various behaviors according to whether they comport with certain rules of action, rather than in terms of their costs or benefits (Piazza & Sousa, 2013; Reference PiazzaPiazza, 2012), and Reference Banerjee, Huebner and HauserBanerjee, Huebner and Hauser (2010) found that across many moral dilemmas, non-religious individuals tended to be more utilitarian. Reference Piazza and LandyPiazza and Landy (2013) later attributed these and subsequent findings to the belief that morality is founded on divine authority. People who believe that moral rules are issued by the divine believe that they must be followed without question (regardless of the consequences). Notably, it appears that the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment cannot be fully explained by intuitive thinking style (Reference Graham and HaidtGraham & Haidt, 2010; Reference Shenhav, Rand and GreeneShenhav, Rand & Greene, 2012); general concern for authority, loyalty, or sanctity (the “binding foundations”, Haidt & Graham, 2010; for a test of this hypothesis see Piazza & Landy, 2014); or general conservativeness (Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012; Reference PiazzaPiazza, 2012; Piazza & Landy, 2014; Piazza & Sousa, 2013).

1.2 Zooming In on Deontology and Religion

The religious tendency towards deontological ethics is well documented. Yet deontology consists of many rules and principles, and these principles may, at times, conflict. Surprisingly, conflicts between deontological principles were rarely studied, although two of the most frequently studied deontological principles — often referred to as the inaction principle and the “intention” (or “indirectness” principle (Reference Cushman, Young and HauserCushman et al. 2006; Royaman & Baron, 2002) — are sometimes in apparent conflict. The inaction principle (also known as the action principle or the doing/allowing distinction) posits that harm caused by action is morally worse than harm caused by inaction (Reference Cushman, Young and HauserCushman et al. 2006; Reference ZamirZamir 2014). As a result, the inaction principle prohibits many harmful actions that aim to mitigate greater harms, even if their benefit outweighs the harm they cause. Psychological studies indicate that the preference for harm from omission over harm from commission — called omission bias — is a common and robust tendency (Reference Baron and RitovBaron & Ritov, 1994, 2004; Reference Tanner, Medin and IlievTanner, Medin & Iliev, 2008). In contrast, the indirectness principle, also known as the doctrine of double effect or the intended/foreseen distinction, prohibits only actions that intend to use a person as a means to an end (Reference Cushman, Young and HauserCushman, Young, & Hauser, 2006; Reference FootFoot, 1967; Reference Royzman and BaronRoyzman & Baron, 2002; Reference ThomsonThomson, 1985). Actions that involve incidental harms as side effects are permitted if they yield better outcomes overall (Kamm, 2008, pp. 93, 138). Notably, although the two principles focus on the nature of the action, they disagree as to what makes an action wrongful (the “doing” element or the “directing” element) and yield substantially different outcomes. For example, in the “trolley problem” the inaction principle would prohibit the killing of one person to save a group of people who would otherwise die by omission (under the premise that allowing the death of the many is less wrong than causing the death of the one). In contrast, the indirectness principle would permit such killing so long as the death of one is a side effect and not the direct means to accomplish the desired end.

Both the inaction and indirectness principles have roots in religious texts.Footnote 1 Previous studies examining the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment often used choice menus that included consequentialist positions (sometimes divided into weak and strong) and absolutist deontological positions that are consistent with the inaction principle (Reference Piazza and LandyPiazza & Landy, 2013; Reference Piazza and SousaPiazza & Sousa, 2014). The relationship between deontology and religiosity was strong. But given the theoretical and practical disagreement between the inaction and indirectness principles, it is unclear what would become of the relationship between religiosity and deontological ethics in the presence of the indirectness principle.

In this paper, we report a series of studies designed to examine the relationship between religiosity and the inaction/indirectness conflict. The introductory cases provide an inspiration to this project, but due to their inherent complexity and many nuances we make no attempt to model them in our studies. More specifically, the paper draws on the trolley problem to design a clear conflict between the inaction and indirectness principles. It then investigates whether disparities in inaction/indirectness judgments can be explained by differences in religiosity. Recent research in the social and political sciences emphasizes that religion is a multidimensional construct and that different dimensions do not always have the same effect on judgment and behavior (Reference SaroglouSaroglou, 2011). For example, Bloom and Arikan (2011, 2013) found that priming religious social behavior facilitates support for democracy, while priming religious belief impedes such support, compared with a control group of no prime. Ginges and colleagues found that support in suicide attacks is predicted from attendance at religious services but not from private prayer to God (Reference Ginges, Hansen and NorenzayanGinges, Hansen & Norenzayan, 2009). These and similar studies suggest that ideological differences can be pinned down to specific dimensions of religiosity, or at least that some dimensions have more influence on moral and ideological positions than others. We therefore examine differences between the behavioral and devotional dimensions of religiosity, measuring service attendance, private prayer, and general belief in God in addition to bringing cross-cultural evidence from Christian-American and Jewish-Israeli samples.

We also examine whether specific beliefs about the role of God can explain moral judgment in the inaction/indirectness conflict. According to Divine Command Theory (Reference Piazza and LandyPiazza & Landy, 2013), the relationship between religion and deontology relies on a particular interpretation of the role of God in setting moral rules. In another line of studies, researchers found that beliefs in powerful, omnipotent Gods are responsible for lower levels of altruistic punishment and support in state-sponsored punishment of moral transgressors (Reference Henrich, McElreath, Barr, Ensminger, Barrett and BolyanatzHenrich et al., 2006; Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin, Shariff, Henrich & Kay, 2012). Laurin and her colleagues explained the reluctance to punish in the attribution of responsibility for that punishment to God (rather than humans; Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012). Intrigued by this explanation, we examined whether belief in divine responsibility also explains differences in moral positions regarding taking action to save lives.

In our final study we also sought to examine the association between religion and moral judgment in an experimental setting. For understandable reasons, most existing evidence on religion and moral judgment is correlational. Some studies found that priming people with religious concepts can reduce cheating (Reference Randolph-Seng and NielsenRandolph-Seng & Nielsen, 2008), increase generosity and cooperation in economic games (Reference Ahmed and SalasAhmed & Salas, 2013; Reference DuhaimeDuhaime, 2015; Reference Shariff and NorenzayanShariff & Norenzayan, 2007), and increase willingness to engage in altruistic punishment (Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012). Religious priming most strongly influences religious individuals (Reference Benjamin, Choi and FisherBenjamin, Choi & Fisher, 2010; Reference Dijksterhuis, Preston, Wegner and AartsDijksterhuis, Preston, Wegner & Aarts, 2008; Reference Horton, Rand and ZeckhauserHorton, Rand & Zeckhauser, 2011) and those interacting with religionists (Reference Bulbulia and MahoneyBulbulia & Mahoney, 2008; Reference GalenGalen, 2012). In the realm of moral judgment, we provide the first experimental evidence, to our knowledge, that religion is not merely associated with deontological judgment, but also influences such judgment.

1.3 Overview of studies

The paper explores the relationship between religiosity, belief, and moral principles using variants of the renowned trolley problem (Reference FootFoot, 1967). In brief, the trolley problem asks people to decide whether or not they would commit an action that would cause one person to be hit by a train in order to prevent that train from hitting five others. In one version of the trolley problem (Reference FootFoot, 1967), which we refer to as “divert”, a person can reach this outcome by flipping a switch that diverts the train away from the five and toward the one. Most people judge this action to be morally acceptable, and indicate that they would perform it. In the contrasting footbridge version (Reference ThomsonThomson, 1985), which we refer to as “push”, to save five people one must push a person off of a footbridge into the path of the train, an action that causes the train to slow down and allows the five people to escape. Most people judge this action to be impermissible and say they would never commit this act.

From a pure utilitarian perspective, judgment in both dilemmas should be identical and favor saving the many at the price of sacrificing the one. From the inaction principle perspective, in both cases the harm of killing the one is worse than the harm of allowing the five to die. But from the perspective of the indirectness principle, there is a morally relevant difference between causing the person’s death in the divert version, which is perceived as a side-effect of saving the five, and causing this death in the footbridge version, where it is perceived as a direct means to accomplish the outcome. In previous research, the indirectness principle seemed to be a major factor leading to different moral judgments in divert- and push-type dilemmas (e.g., Greene et al., 2009). However, the role of the indirectness principle in the divert case is unclear because a choice to divert the trolley can be interpreted either as adherence to utilitarianism or as adherence to the indirectness principle, which permits this choice but would not permit choices that involve direct use of others as a means.

To create a direct moral conflict between utilitarianism, the indirectness principle, and the inaction principle, we follow Barak-Corren, Tsay, Cushman & Bazerman (2017). Similar to their design, we presented participants with a moral trilemma in which they stood between two sets of railroad tracks. On the left, the push case was presented; the participant could choose to run and push a large person in front of a train in order to prevent it from hitting five people (Figure 1). On the right, the divert case was presented; the participant could choose to run to flip a switch that would divert the train onto another track, such that it would hit one person on the sidetrack but save three people (rather than the five people typically specified in trolley problems). Alternatively, participants could choose to do nothing at all.

Figure 1: Above: Push. Below: Divert. The illustration was presented immediately after the textual description of the case.

Participants were asked to read the following scenario and assume that all the information in it is true and that the outcomes are certain:

You are working by the train tracks when you see two empty boxcars break loose and speed down separate tracks: Track A and Track B.

One (Boxcar A) is heading toward five workmen who do not have enough time to get off the main track. If you do nothing, these five workmen will be killed. Standing on a footbridge spanning the tracks is another worker, who is very large. This worker is not threatened by the boxcar. But, you can run over to push him off the platform in front of the boxcar. The man would be killed, but his body is large enough that the impact will slow down the boxcar and allow the five workmen to escape.

The other (Boxcar B) is heading toward three workmen who do not have enough time to get off the main track. If you do nothing, these three workmen will be killed. Just before the three workers there is a side track branching off of the main track. On this side track there is one other worker. You can run over and flip a switch that will send the boxcar down the side track. The man on the side track would be killed, but the boxcar would not hit the three workmen on Track B.

You only have time to do one action — you can push the man or flip the switch, but not both. You know exactly what your choices are (as just specified), and are certain (as specified) about what would happen in each case.

This design provides the opportunity to tease out the three moral approaches by creating a salient conflict among three moral principles: utilitarianism, represented by the push option that follows the best outcome in terms of number of lives saved; the inaction principle, represented by the inaction option, which follows the duty to do no harm; and the indirectness principle, represented by the divert option, which allows the justification of an indirect harm that serves a good cause (Reference Barak-Corren, Tsay, Cushman and BazermanBarak-Corren et al., 2017). By teasing out moral choice in each of the three principles we are able to examine potential differences in religiosity between followers of each principle. Our first goal was exploratory. Given previous research about the relationship between religion and deontology on the one hand, and the moral difference between the inaction and indirectness principles on the other, we were interested to learn whether there are any differences in religiosity between adherents of the inaction and indirectness principles. Following Laurin and colleagues (2012), we also examined the more specific hypothesis that belief in divine responsibility for human suffering may explain inaction judgments, as opposed to indirectness judgments. Therefore, we were primarily interested in differences between inaction and indirectness judgments. Utilitarian judgments served as a necessary reference point to understand how different deontological principles fare in comparison to utilitarianism. In line with the literature, we expected followers of utilitarianism to be less religious than followers of both deontological principles. We test the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment in three studies, conducted in predominantly Christian and Jewish environments. Two of our studies are correlational; the third is experimental.

To conclude, we note that our use of the trolley problem is not motivated by any great interest in railway ethics, and there are disadvantages to studying moral decision-making in such an unusual context (Reference Bauman, McGraw, Bartels and WarrenBauman, McGraw, Bartels & Warren, 2014). These are outweighed in the present case by three key advantages. First, the trolley problem has been extensively studied, and our experimental approach and hypotheses draw extensively upon the specific lessons of this existing literature. Second, the trolley problem captures the competition between the moral principles at the focus of this research — the indirectness and the inaction principles — vividly, robustly, and reliably across individuals, more than other dilemmas we have considered. Third, though trolley dilemmas may generally lack realism, they do correspond with the “sacrificial” trade-off of life and death that characterize our introductory cases. Trolley-like dilemmas are also no strangers to religious thought. Jewish philosophers, for example, used sacrificial dilemmas to discuss conditions for permissible harm (Reference KarelitzKarelitz, 1954, p. 25). To be sure, the trolley problem does not model the real-world conflicts we surveyed in any precise way. But, for the reasons above, we believe that its setup elicits some of the basic intuitions that participate in shaping moral judgment in these cases and others.

2 Study 1: Moral Judgment and Religiosity among U.S. Christians

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

A total of 600 participants in two samples were recruited to participate in the study via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (mTurk) in exchange for monetary compensation. Only individuals located in the United States were allowed to participate. Attention was checked at the beginning of the experiment, and those who passed proceeded to participate in the study (86%). The final number of participants was 489 with an average age of 33.54; 212 were women.Footnote 2

2.1.2 Procedure

Participants read the text of the dilemma, followed by the illustration (see text and Figure 1 above). Thereafter, participants were asked “What would you do?”Footnote 3 The menu included three options: flip the switch, push the man, or do nothing. On the next screen, participants provided a free-text explanation to their choice, which we later analyzed. The next section included an internal control of whether participants previously had participated in a trolley study. (Participants were asked to answer this question truthfully and were assured that their answer would not affect their compensation; no differences were found based on this measure.)

Religiosity was measured at the end (embedded in the demographics section), along three dimensions (Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012; Reference Malka, Soto, Cohen and MillerMalka, Soto, Cohen & Miller, 2011; Reference Shenhav, Rand and GreeneShenhav et al., 2012): (1) Personal religiosity was assessed using five items, each with a 1–7 response scale (“How strongly do you believe in God or gods?” “To what extent do you consider yourself religious?” “To what extent are religion or faith a big part of your life?” “To what extent do you identify with your religion?” “How often do you think about religion or being religious?”) (Cronbach’s alpha = .975); (2) private prayer, i.e., prayer outside of formal worship, was measured on a 1–6 scale ranging from “never” to “daily” and including options such as “2–3 times a week” and “once or twice a month”; and (3) attendance in religious services was measured on a similar 1–6 scale. Scales were adapted from Malka et al. (2011). All religiosity measures are included in the appendix.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Religiosity and choice

The three measures of religiosity correlated highly with one another (r(religiosity, prayer) = .74; r(religiosity, attend) = .66; r(attend, prayer) = .5; ps < .001), suggesting good convergent validity.

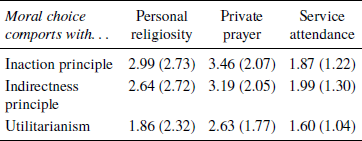

Given the structure of our data (a three-level categorical DV and predictors treated as continuous) we used multinomial logistic regressions to examine the impact of each of the three measures of religiosity on the extent to which participants endorsed the inaction principle, the indirectness principle, or utilitarianism. We used the divert option as the reference category, comparing indirectness judgments to inaction judgments, on one hand, and utilitarian judgments, on the other hand. To complete the picture, we also report the results of the inaction/push contrast, derived from the same analysis with the push option as the reference category. The analysis and results remain the same regardless of the reference point chosen.Footnote 4 As Table 1 shows, significant effects of personal religiosity and private prayer emerged (Wald χ2 = 14.931, p = .001; Wald χ2 = 14.201, p = .001 respectively). More religious participants preferred the two choices comporting with deontological principles (Divert, χ2(1, N = 145) = 6.11, p = .01, and Inaction, χ2(1, N = 221) = 14.00, p = .000) over the utilitarian option (Push), as did participants who prayed in private more frequently ( p = .02, p = .000 respectively). Service attendance had a somewhat weaker effect on moral choice ( Wald χ2 = 7.4, p = .024), which did not remain statistically significant after accounting for gender (Wald χ2 = 5.47, p = .065).

Table 1. Predicting the probability of deontological vs. utilitarian choices from personal religiosity, private prayer and service attendance, Study 1.

Note: The table reports multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting moral choice from each dimension of religiosity. The first two rows report the model when divert (indirectness principle) is the reference category. The last row reports the third contrast from the same model when push (utilitarianism) is used as the reference category. Omnibus Chi-Square tests of the personal religiosity and private prayer models were all significant at the .001 level; for service attendance the omnibus Chi-square test of the model was significant at the .05 level. Coefficients are unstandardized due to the analysis — multinomial logistic — and the variation in predictor type between and within models — continuous and categorical.

* p <= .05

** p <= .01

*** p <= .001

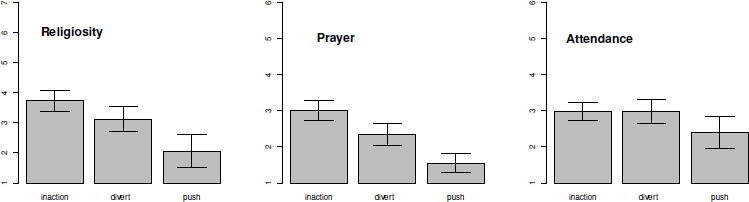

Figure 2 and Table 2 show that the effect of religiosity on moral choice was driven largely by differences between the two deontological choices, on the one hand, and the utilitarian choice, on the other hand. No analysis found significant differences in religiousness between indirectness and inaction choosers, but they were both significantly more religious than utilitarian choosers.

Figure 2: Religiosity and moral choices in the U.S. (study 1). Higher levels of personal religiosity and private prayer are associated with deontological decisions in a trolley trillema (p values = .001). Differences in service attendance were smaller and not robust.

Table 2. Means and SD of different dimensions of religiosity according to moral choice.

Note: the deontological choices were highly associated with personal religiosity (F(2,486)= 7.675, p= .001) and private prayer (F(2,486)= 6.873, p= .001) relative to the utilitarian choice. Service attendance had a weaker relationship with moral choice that became not significant when controlling for demographic variables (F(2,486)= 3.54, before controls: p = .03; after: p = .117).

We note that previous work has tied age and gender both to moral judgment and to religiosity (Reference Argue, Johnson and WhiteArgue, Johnson & White, 1999; Reference Banerjee, Huebner and HauserBanerjee et al., 2010; Reference FrancisFrancis, 1997; Reference Loewenthal, MacLeod and CinnirellaLoewenthal, MacLeod & Cinnirella, 2002). Age and gender were significant predictors in models that included them as covariates, in the direction expected in light of previous research – older participants were more deontological than younger participants, and women were slightly more likely to choose inaction than men. Being older and being a woman were also significant correlates of religiosity (r religiosity,age= .284, p < .001, r religiosity,gender = .172, p < .001; this was also expected given previous research on Christians: Argue et al., 1999; Reference FrancisFrancis, 1997; Reference Loewenthal, MacLeod and CinnirellaLoewenthal et al., 2002). The relationship between personal religiosity and private prayer, on one hand, and moral judgment, on the other hand, remains statistically significant even after accounting for gender, but we cannot draw conclusions about the role of age because, unlike gender, age is an imperfect measure of whatever underlying trait accounts for its correlations (e.g., cultural change over historical time; see Reference Westfall and YarkoniWestfall & Yarkoni, 2016). We address these issues in Study 2.

2.2.2 Textual Analysis

To further explore the differences between the choosers of each option, we conducted a natural language processing of the short free-text explanations that participants provided to their choices using Python and NLTK (http://www.nltk.org). Using a Naïve Bayes Classifier (code: http://www.nltk.org/\_modules/nltk/classify/naivebayes.html), we used 50% of the textual answers to build a naïve Basysian model to distinguish between each pair of choices (inaction/push; push/divert; divert/inaction) and then tested the model on the remaining 50%. We also ran additional checks on popular pairs of adjacent words to complement the model (using the function nltk.Text(choice2Tokens)).collocations).

Interestingly, the textual explanations given for the utilitarian choice (push) were, on average, half the length of the two other groups (Mpush = 79.1 words; Mdivert = 150; Minaction = 145.1, p < .001), perhaps indicating that utilitarian participants saw the choice as easier or simpler to explain than did deontologist participants. However, no measures of religiosity correlated with response length. Supporting the quantitative findings, the textual analysis revealed that utilitarians were more outcome-oriented. They used words like “most”, “more”, “many”, and “least” and referred to the numbers of people on the tracks (e.g., 3, 4, 5) at a much higher rate than the inaction principle group did. For example, “most” was mentioned 37 times by utilitarians for each time it was mentioned in the inaction principle group, a 37:1 ratio and 8.8 times for each time it was mentioned in the indirectness principle group, an 8.8:1 ratio.

Differences between the textual explanations in the indirectness principle and inaction principle groups were more nuanced. Many diverters emphasized their aversion from physical contact (the rate of “physically” was 5.8:1 compared to utilitarians) and the nature of their action (“flipping”, “diverting” was mentioned 7.7:1 compared to the inaction group). People who chose inaction, by contrast, emphasized that taking any action is an immoral choice. They frequently referred to the word “action” (9.3:1), usually along the lines of, “If I choose to take any action, I would cause someone’s death.” Their negative use of “should” (6.5:1) and “responsible” (5.4:1), as in “It should not be my decision” or “I don’t want to be responsible”, was very high. They also frequently referred to God, fate, or destiny as being responsible for the situation and as playing a role they cannot assume (e.g., “Mainly, I cannot play God in this situation”, “Yes, the numbers work, but who am I to play God?” and “I cannot interfere with fate and God’s plan”).

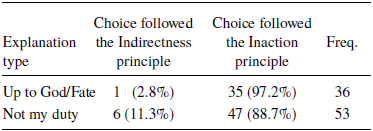

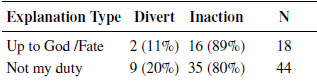

As Table 3 shows, a Chi-square test on the frequencies of God-like references in the explanations of Indirectness and Inaction revealed that “it’s up to God” explanations were used almost exclusively by Inaction choosers (χ2 = 22.684, p < .001). The same was true with regard to negative duty words and phrases, such as “should not” or “not responsible” (χ2 = 20.768, p < .001). Overall, 33% of the people who followed the inaction principle appealed to such explanations, compared with only 5% of the people who followed the indirectness principle and less than 1% of the utilitarians. Significant correlations were observed between up-to-God explanations and religiosity.Footnote 5

Table 3. Study 1 - Word Frequencies in Indirectness and Inaction Choices

Note: all numbers refer to individuals. If an individual referred to several concepts from the same category (row), we counted him/her only once in that row.

Finally, to examine whether up-to-God explanations differentiated between religious people who followed the indirectness principle and religious people who followed the inaction principle, we conducted an integrated analysis of deontological choices (Indirectness/Inaction) by religiosity (dichotomized based on the mean into high/lowFootnote 6) and up-to-God explanations (yes/no). Four groups were formed: low religiosity and up-to-God explanations; low religiosity and no up-to-God explanations; high religiosity and up-to-God explanations; high religiosity and no up-to-God explanations. The differences were striking. Highly religious people and frequent private worshipers who wrote up-to-God explanations were all clustered in the inaction principle cell (0% v. 100%), whereas highly religious people who did not rely on God were relatively split between the indirectness and inaction principles (44% v. 56%), (χ2 = 23.315, p < .001) and the same was true for frequent private worshipers (42% v. 58%, χ2 = 22.432, p < .001). Conversely, service attendance had no significant relationship with up-to-God explanations and people who attended services frequently were not more likely than those who did not attend to appeal to God.

2.3 Discussion

Study 1 revealed a strong effect of religiosity on deontological moral judgment, consistent with past research. At the same time, our results point to a more nuanced relationship between religiosity and deontology than previously identified. First, we show that in a conflict between several moral principles, religious individuals divide between the inaction principle and the indirectness principle, preferring either passive harm or indirect harm. Second, the data suggest that the religious inclination toward deontological moral judgments is primarily a function of personal religiosity and private prayer rather than a function of public, social behavior such as participation in religious services, although the difference in correlations with utilitarian responding between attendance (.16) and prayer (.11, also measured by a single item) was not significant by a test for difference of dependent correlations.

Our findings suggest that the deontological divergence among the religious is driven by a belief in God’s responsibility for human tragedy. The focus on the responsibility of supernatural powers as a justification for denouncing personal responsibility highly distinguished Inaction followers from Indirectness followers, though both groups were similarly religious and significantly different from those who chose to maximize outcomes, regardless of the action. These findings nuance our understanding of the relationship between religion and deontological judgment, as they suggest that different religious concepts on the scope of supernatural responsibility versus personal responsibility underlie differences in moral judgment. Interestingly, the findings also show that, while religious individuals avoid purely consequentialist judgments, some do consider outcomes alongside action – as long as they do not think it is up to God, rather than themselves, to make the decision.

3 Study 2: Religiosity and moral choice in a Jewish Israeli population

Our findings in a Christian-American culture led us to explore whether the relationship between religiosity and the two types of deontological judgment extends to other cultural-religious contexts. To date, moral judgment in trolley problems was mostly studied with English-speaking populations in North America and the UK. Studies that examined other cultures found mixed evidence. One large-scale study found that people of Western and non-Western cultural and religious affiliations (including Christians and Jews) mostly make similar judgments in trolley and trolley-like dilemmas (Reference Banerjee, Huebner and HauserBanerjee et al., 2010) and another cross-cultural study found that both Indians and Americans distinguish acts from omissions (Reference Baron and MillerBaron & Miller, 2000). Yet studies also found differences in moral judgment in trolley and other dilemmas between British and Chinese (Reference Gold, Colman and PulfordGold, Colman & Pulford, 2014), Americans and Indians (Reference Baron and MillerBaron & Miller, 2000), and American Jews and Protestants (Cohen & Rozin, 2001). For example, Cohen & Rozin (2011) found differences in the moral status attributed to thoughts: Christians were more likely than Jews to judge adulterous thoughts as immoral even if no adultery was committed. Given the mixed evidence regarding religious differences in moral judgment and our specific focus on the inaction/indirectness contrast, we sought to explore the generality of our findings by examining whether Jews and Christians would be similarly inclined to diverge between the indirectness and inaction principles and provide similar reasons. Notably, while Judaism and Christianity differ in many ways, they also share a core belief in one, powerful God that directs the course of the universe, and both seem to support the inaction principle (the “do no harm” principle, Exodus 20:13; J.T. Trumot 8:4) and the indirectness principle, or some such (Acuinas, 13th c.; see Karelitz, 1954, for the idea that killing to serves a good end might be permissible). We therefore expected that our results would replicate in a Jewish population.

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Three-hundred and thirty students from a large Israeli university participated in the study.Footnote 7 The diverse sample included business, education, psychology, economics, arts and sciences, and law students (Mage = 26.56 years, SDage = 5.29, 203 women); 89% identified as Jewish, 8% as atheist or agnostic, and the rest were Muslim or unaffiliated. Notably, the Jewish population in Israel is very diverse in terms of actual religiosity, as many identifying Jews are not practicing and some may not believe in God, yet would not identify as atheists. Therefore, as in the U.S., we measured the extent to which our participants prayed, attended services and believed in God (see below).

3.1.2 Procedure

Since we were unaware at the time of our study of any Middle Eastern study of the trolley problem, let alone one conducted with a sufficiently large sample of a Hebrew-speaking population, we wanted to establish the baseline of moral judgment in each of the basic trolley problems in our population. To this end, the study included three conditions. Each participant was randomly allocated to see either the trilemma used in Study 1 or one of the two trolley dilemmas separately, Divert or Push. The scenarios of the separate dilemmas were adopted from Study 1 with identical wording. The Push text read (Divert text in brackets):

You are working by the train tracks when you see an empty boxcar break loose and speed down the tracks. The boxcar is heading toward five [three] workmen who do not have enough time to get off the main track. If you do nothing, these five [three] workmen will be killed.

Standing on a footbridge spanning the tracks is another worker, who is very large. This worker is not threatened by the boxcar. [Just before the three workers there is a side track branching off of the main track. On this side track there is one other worker.] But, you can run over to push him off the platform in front of the boxcar. [You can run over and flip a switch that will send the boxcar down the side track.] The man would be killed, but his body is large enough that the impact will slow down the boxcar and allow the five workmen to escape. [The man on the side track would be killed, but the boxcar would not hit the three workmen on Track B.]

Identical measures of religiosity were used, and the questionnaire was translated to Hebrew to avoid possible foreign language effects on moral judgment (Reference Costa, Foucart, Hayakawa, Aparici, Apesteguia, Heafner and KeysarCosta et al., 2014). The study was thus conducted in participants’ native language and included three conditions: Divert, Push, and the trilemma that jointly contrasted the two. Each participant was randomized to participate in one condition only.

3.2 Results

We first examined the patterns of moral judgment in all three conditions of the Jewish Israeli sample to address possible cultural differences in moral judgment. The results followed the patterns documented in previous studies: Most people preferred diverting to inaction in the separate Divert dilemma (55% v. 45%) but preferred inaction to pushing in the separate Push dilemma (90% v. 10%) (compare to Hauser, Cushman, Young, Kang-Xing Jin & Mikhail, 2007). We thus proceeded with analyzing the relationship between moral judgments and religiosity in the condition of interest, the joint trilemma (N=106), according to the analysis used in Study 1. The results are summarized in Table 4.

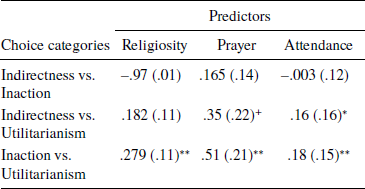

Table 4. Predicting the probability of deontological vs. utilitarian choices from religiosity: The Jewish Israeli sample.

Note: The table reports multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting moral choice from each dimension of religiosity. The first two rows report the model when divert (indirectness principle) is the reference category. The last row reports the third contrast from the same model when push (utilitarianism) is used as the reference category. The Omnibus Chi-Square test of personal religiosity model was significant (p = .028). The Omnibus Chi-Square test of private prayer was significant (demographics not controlled: p =.016. For service attendance the omnibus Chi-square test of the models was not significant.

+ p <= .10

* p <= .05

** p <= .01

We used a series of multinomial logistic regressions to examine the impact of each of the three measures of religiosity — personal religiosity, private prayer, and service attendance — on the extent to which participants endorsed the inaction or indirectness principles versus utilitarianism in the trilemma group (106 participants). As Table 4 shows, significant effects of personal religiosity and private prayer emerged (Wald χ2 = 7.186, p = .028; Wald χ2 = 8.273, p = .016 respectively). Perhaps due to the smaller sample size, these effects were weaker than in Study 1 and strongest in the Push/Inaction contrast. Private prayer emerged as the better predictor of moral choice in this sample. Participants who prayed more often preferred the two deontological choices (Divert over Push, χ2(1, N = 32) = 2.6, p = .053 one tail; and Inaction over Push χ2(1, N = 51) = 6.28, p = .005 one tail). Conversely, service attendance had no effect on moral choice (M5: Wald χ2 = 1.82, p = .403, M6: Wald χ2 = 3.42,p = .181). Figure 3 and Table 5 provide a more descriptive account of the results.

Figure 3: Religiosity and moral choices in Israel (study 2). Higher levels of personal religiosity and private prayer, but not attendance in services, are associated with deontological decisions in a predominantly Jewish sample in Israel. Means and SDs are provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Means and SD of different dimensions of religiosity according to moral choice – Study 2.

Note: the deontological choices were significantly associated with personal religiosity (F = 3.6, p = .03) and private prayer (F= 5.42, p = .006) relative to the utilitarian choice. Service attendance was not significant (F= .84, p = .43).

In this sample, age did not correlate negatively with utilitarian responding, as it did in Study 1. Its correlations with Push, personal religiosity, and private prayer were very low (.02, –.11, –.07) and not close to significant. This result thus largely lays to rest the possibility of confounding with age that we observed in Study 1. Likewise, gender did not correlate with measures of religion and, once again, cannot account for the main results.

3.2.1 Textual Analysis

To further understand the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment, we again analyzed participants’ textual explanations. Drawing on the findings of Study 1, we searched for participants’ use of God-like words and negative use of personal duty words in Hebrew. (Due to difficulties in Hebrew-language processing, we used basic searches and word counts.) As Table 6 shows, the analysis reveals significant differences between deontological choices in references to God, fate, and destiny, and in the assumption of personal responsibility: People who followed the inaction principle were much more likely to refer to God, fate, faith, and religious law (Halakha), arguing that taking action is up to God, as compared to indirectness principle followers (χ2 = 7.55, p = .023). Notably, as in Study 1, not even one person in the utilitarian group used religious words to explain their choice. The use of words referring to duties, such as “should”, “responsible”, “authorized”, etc., was particularly and significantly frequent in the Inaction group as compared to other groups (χ2 = 9.068, p = .011) and was always in the format of “this is not my responsibility” or “I am not authorized to intervene.”

Table 6. Study 2 — word frequencies in indirectness and inaction choices

Note: all numbers refer to individuals. If an individual referred to several concepts in the same category (row), we counted their response only once.

3.3 Discussion

Study 2 replicates the results of Study 1 in a predominantly Jewish-Israeli sample, establishing the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment also outside of North America and in a non-Christian population. Less religious participants emerged as more consequentialist, whereas more religious participants preferred more deontological responses, primarily the inaction principle. Adherents of the indirectness principle, who pay attention to both actions and outcomes (choosers of Divert) were not distinguishable from adherents of the inaction principle (choosers of Inaction), although they were also hard to distinguish from consequentialists on some religiosity measures. Interestingly, Study 2 replicated also the apparent finding that moral choices are better predicted from personal religiosity and private prayer than from more public and social manifestations of religiosity, such as service attendance, although, again, the differences in dependent correlations were not significant.

Indirectness and inaction deontologists were similar (as far as the data shows) in the traditional religious sense of general belief, religious identity, and frequency of prayer, but they differed in their concepts of personal and supernatural responsibility. Together, Studies 1 and 2 suggest that the tension between deontological positions involves more specific religious concepts. A belief in supernatural responsibility might leads individuals to refrain from harmful actions that save lives, whereas a belief in personal responsibility might lead them to choose harmful actions that save at least some lives. A question still remains, whether these beliefs actually guide moral judgment or are they merely invoked as post-hoc justifications (Reference HaidtHaidt, 2001). More generally, do people in a religious environments become more deontological, and if so, does belief in supernatural responsibility moderates their choice of principle? Study 3 attempts to examine this question.

4 Study 3: Is Sunday special? A quasi-experimental study

In Study 3, we examine the direction of the relationship between religion and deontological moral judgment and whether a religious setting directly influences moral judgment. Our experimental design follows Malhotra (2010) in exploiting the natural religious setting created by the existence of a Christian holy day on the weekly calendar: Sunday. We conduct a quasi-natural experiment among U.S. Christians comparing moral judgment on Sunday to moral judgment on a regular weekday. We expect the Sunday setting to influence the moral judgment of the religious, such that religious people will be more likely to make deontological choices on Sunday versus regular days. In accordance with Malhotra (2010), we expect only religious people to be influenced by Sunday; this is consistent with previous findings that various manipulations aimed at increasing religion’s saliency primarily influence those who are religiously affiliated and/or those who believe in God. These manipulations had no or even reverse effects on non-believers (Reference Benjamin, Choi and FisherBenjamin et al., 2010; Reference Dijksterhuis, Preston, Wegner and AartsDijksterhuis et al., 2008; Reference Gervais and NorenzayanGervais & Norenzayan, 2012; Reference Horton, Rand and ZeckhauserHorton et al., 2011; Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012; Reference Shariff and NorenzayanShariff & Norenzayan, 2007).Footnote 8

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Participants

We recruited participants on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk during two weekends. Only U.S. participants were allowed to participate, and only participants who affiliated Sunday with religious services were included in the sample (N = 471, see Appendix for the text of the question). The analysis included only participants who provided consistent responses (83.2%; N = 392, 184 women).Footnote 9 About half the responses were collected on Saturdays and the other half on Sundays. We limited data collection to Saturday and Sunday for two reasons: first, Malhotra (2010) found that the Sunday effect does not spill over to Saturday or Monday, and that the other days do not differ among themselves. These findings allowed us to focus on one day for the purposes of comparison to Sunday, which made for a clean and simple design. Comparing Saturday to Sunday also allowed us to insulate any religious effect that Sunday may have from effects associated with leisure and rest that might characterize weekend time more generally.

4.1.2 Procedure

Following consent, the study participants first answered questions about their morning activity. They were asked to choose from a list of seven options (met friends, went to Church, stayed at home, went to work, other, etc.) and then write about their activity in more detail. The list was identical on both Saturday and Sunday and included church attendance as an option for both days. This conservative design was intended to make the religious context of Sunday salient while keeping everything else but the day in which the study was taken constant between Saturday and Sunday. We expected that any Sunday effect would derive mainly from external sources — the natural religious setting of that day — and not from our light manipulation. (As noted above, only participants who referred to Sunday as the day of religious services were included in the sample.)

Following the introductory task, participants read the same moral trilemma used in Studies 1 and 2: a joint trolley problem in which they were requested to choose between three options: Push to save five people, Divert to save three people, and Inaction to save no one. On the next screen, they were asked to rate the morality of each option on a scale ranging from 1–10.Footnote 10 This design allowed us to collect two outcome measures while keeping the flow of the study virtually identical to the flow of the first two studies. Participants first provided their choices and only then rated the three options on a scale, maintaining the integrity of their initial selection and its comparability to previous studies. The morality scores were mostly intended to capture more nuanced effects (see below).

Finally, participants provided demographic information, including religiosity. As in previous studies, all measures of religiosity were collected at the end of the study. This design allowed us to separate our measurement of religiosity from our religious context manipulation, as participants on both Saturday and Sunday were asked questions about their religious beliefs only after they answered the moral trilemma. Religiosity was measured identically to Studies 1 and 2. In the present study, we included measures of belief in powerful, responsible Gods (adapted from Laurin et al. 2012: “To what extent do you think that God or some type of nonhuman entity is in control of the events in the universe?” and “To what extent do you think that events in the universe unfold according to God’s, or some other supreme being’s, plan” on a 1–7 scale). These measures allow us to explore whether the pattern discovered in participants’ textual responses in Studies 1 and 2 contributes to explaining moral judgment in the experimental setting.Footnote 11

4.2 Results

We first explored the demographics of our sample on Saturday and Sunday to examine whether recruitment was balanced or differed between days. Comparing Sunday to Saturday, no differences were found in participants’ religiosity (p = .893), belief in powerful gods (p = .772), race (p = .326), or income (p = .1). Participants on Sunday were slightly younger than those on Saturday (MSunday = 31.4 years, SD = 10.72 vs. MSaturday = 34.3 years, SD = 12.5, p = .016) and there were more women on Sunday (54% vs. 40% on Saturday). We thus account for age and gender in further analyses. Twenty-one percent of the sample attended services at least once or twice a month, as compared to 37% of U.S. adults who attend weekly (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2012), which makes our sample less observant than the general U.S. population.

Religiosity and private prayer were highly correlated in this sample (r =.834, p <.001) and were converged into one personal religiosity measure, distinct from the public dimension of service attendance, by converting them into Z scores and averaging the items (Cronbach’s alpha = .96). We then submitted the data to a multinomial logistic regression predicting choice from religiosity, day (0 for Saturday, 1 for Sunday), and their interaction (Day was centered to compute the interaction). The model was significant (model χ2 = 17.11, p = .029), and the analysis revealed a highly significant interaction effect: On Sunday, as compared to Saturday, religious people were more likely to make a deontological choice (inaction or divert) than a utilitarian choice (push) (Divert relative to Push, χ2(1, N = 150) = 7.34, p = .007; Inaction relative to Push, χ2(1, N = 185) = 7.177, p = .007).Footnote 12 The weekend during which participants took the survey had no effect on the results, and the interaction remained highly significant with demographics in the model, with no significant changes in the unstandardized beta coefficients. Religiosity had a significant main effect (p = .019), which was stronger in the inaction relative to push contrast (Divert relative to Push, χ2(1, N = 150) = 3.473, p = .06; Inaction relative to Push, χ2(1, N = 185) = 6.873, p = .009). Age had no effect; and although women were more inclined to inaction than men (p = .031), similar to study 1, there was no significant difference between the responses that either gender provided on Saturday versus Sunday (p’s = .26, .5). Hence, our results cannot be explained by age or gender.

Consistent with Studies 1 and 2, the day by service attendance interaction, unlike the day by personal religiosity interaction, was only weakly correlated with moral choice, and its model was not significant (p = .416).

Following our findings in Studies 1 and 2, we then examined the more nuanced hypothesis that belief in supernatural responsibility distinguishes indirectness and inaction deontologists: those choosing to divert the trolley versus those choosing inaction. We analyzed the impact of belief in powerful, responsible gods (after averaging the two items into one Belief in Powerful Gods, or BPG for short, score) on participants’ moral choices and their ratings of each of the three options. Notably, the analyses are qualified by a particularly high correlation between BPG and personal religiosity (r = .842, p < .001), which prevented a meaningful exploration of their interaction. We thus limit our analysis to the interaction between day and BPG.

Following Studies 1 and 2, our hypothesis was that on Sunday people who believe in powerful, responsible Gods would become more likely to endorse inaction — but not one of the other moral principles. To test this hypothesis, we regressed each of the moral ratings — those for the utilitarian choice (Push), the indirectness principle choice (Divert), and the inaction principle choice (Inaction) — on BPG, age and gender and their interaction with Day. As expected, the moral rating of Inaction showed a positive and significant interaction effect between Day and BPG (p = .040, two-tailed), but Divert and Push showed no such effect.Footnote 13 Gender and age were not significant. In other words, on Sunday, people who believed in powerful, responsible gods (BPG) were more likely to think inaction is moral, but not more likely to think diverting (or pushing) are more or less moral.

Across all days, personal religiosity was negatively correlated with the rating of Push (r = –.13, p = .02) and positively correlated with the rating of Inaction (.101, p = .076. Interestingly, religiosity was negatively correlated with the rating of Divert (–.133, p = .018), suggesting once again that religiosity can affect the inaction principle as well as the indirectness principle.

4.3 Discussion

A quasi-natural experiment exploiting the religious atmosphere on Sunday in the United States compared moral judgment on Sunday to a comparable non-religious day, Saturday. The results provide causal evidence that a religious setting yields more deontological moral judgments. As expected, this effect works selectively on religious people – that is, Sunday enhances the deontological judgment of religionists, but not seculars. Justifications from Studies 1 and 2 suggested that a belief in divine responsibility differentiates religionists who adopt the indirectness principle from those who adopt the inaction principle. Being religious in a religious atmosphere (Sunday) promotes deontological judgment but does not determine the exact deontological position one is likely to take. Rather, the results of Study 3 suggest that it is the particular belief in powerful gods that emerges as the factor responsible for inaction. These findings support and expand our previous results, showing that divine responsibility is not merely a post-hoc justification of inaction choices, but that the belief in powerful, responsible Gods selectively increases the appeal and perceived morality of inaction on Sunday.

5 General Discussion

Across three studies, we showed that moral judgment is tied to and shaped by religiosity, religious context, and specific religious beliefs. When facing ethical dilemmas, religious participants from both U.S. Christian and Israeli Jewish backgrounds were likely to form deontological moral judgments and to give more weight to the nature of the action open to them than to the expected outcomes of that action. Furthermore, religious participants (U.S. Christians) became more deontological on Sunday, as compared to Saturday.

Our findings on the relationship between religiosity and deontological moral judgment corroborate and expand prior research. In line with previous correlational studies (Reference PiazzaPiazza, 2012; Reference Piazza and LandyPiazza & Landy, 2013; Reference Piazza and SousaPiazza & Sousa, 2014), we show that deontological judgment is strongly correlated with high religiosity. Further, we present unique experimental evidence showing that a religious context causally increases deontological thinking among people of faith. Third, our studies reveal a nuanced account of the relationship between religiosity and morality by focusing on moral principles and the tension within deontological morality. While religious individuals are generally more deontological, they also differ systematically in their positions on central deontological principles. Our data suggests that these differences are tied to and influenced by specific beliefs about the role of God versus man in responsibility for human tragedy.

As both the data and real-life examples demonstrate, this moral divergence can have significant consequences. Focusing on the prevention of intended harm rather than any harm has significant implications in moral conflicts. Similar to the St. Joseph Hospital case, religious individuals and organizations often struggle with moral dilemmas that contrast favorable outcomes (e.g., saving a young woman’s life) with aversive action paths (e.g., authorizing a procedure that terminates a pregnancy). Our data highlights the importance of middle paths that allow believers to choose, among various benefit-harm trade-offs, the lesser, unintended harm that can yield better consequences than inaction. One example that is highly relevant to our studies is the case of euthanasia, which repeatedly agonizes religious care-providers and families. The Catholic “Declaration on Euthanasia” forbids any form of active euthanasia, but allows alleviation of pain in the dying and the forgoing of “aggressive medical treatment”, even with the shortening of life as an unintended side effect (John Paul II, 1995, §65). This policy creates a middle path for believers to provide end-of-life care and relieve end-of-life suffering (albeit the prohibition on active euthanasia may still leave many patients with no solution for their misery). Jewish law also prohibits any form of active euthanasia, including the withdrawal of artificial life-sustaining therapy, even if the patient has requested it. Conversely, Jewish law allows and sometimes even prescribes palliative care that might unindirectnessally shorten life (Reference Steinberg and SprungSteinberg & Sprung, 2006). Notably, these policies pay tribute to both the inaction and the indirectness principles without relieving their tension. We find them in other Christian denominations, in Islam, and in other world religions (Reference Bülow, Sprung, Reinhart, Prayag, Du and ArmaganidisBülow et al., 2008; Reference SachedinaSachedina, 2005). Some religions make additional fine-grained distinctions, for example between continuous and intermittent life-sustaining treatment. Such distinctions provide decision-makers with additional moral latitude by viewing each individual unit of treatment as a new action that may be omitted (Reference Steinberg and SprungSteinberg & Sprung, 2006). Future research could examine the psychology of these important nuances in religious moral judgment.

If both the inaction and indirectness principles are compatible with religious ethics, what leads people of faith to choose a particular path when the two principles directly conflict? Across three studies and two cultures, we found no significant differences in personal religiosity, frequency of private prayer, or service attendance between indirectness and inaction deontologists (though both significantly differed from consequentialist participants). Gender, age, race, education, and income also failed to mediate the relationship between religiosity and moral judgment. A textual analysis of participants’ free-text justifications in Studies 1 and 2 suggested one possible answer: the belief that God, rather than man, is responsible for life and death. Participants who followed the inaction principle differed from participants who followed the indirectness principle in one apparent way: they attributed responsibility to tragic trade-offs to God and denounced their own responsibility for the outcomes. We tested this mechanism in the quasi-experimental setting of Study 3 using a measure of belief in supernatural control (Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012) and found that the more participants believed in supernatural responsibility, the more they thought inaction to be moral on a Sunday.

These findings suggest that personal religiosity promotes deontological moral judgment and belief in supernatural responsibility is the specific mechanism that influences whether a person follows the inaction or indirectness principle within deontology. These findings extend the work of Reference Piazza and LandyPiazza and Landy (2013) who found a strong relationship between the belief that morality is rooted in divine authority and deontological judgment. The present research exposes another dimension of supernatural beliefs and their impact on moral judgment, and shows how beliefs in powerful and responsible Gods can also explain different religious positions within deontological ethics. Our findings also correspond with prior works that found that beliefs about the character and attributes of God (or gods) have an impact on prosocial behaviors (Reference Laurin, Shariff, Henrich and KayLaurin et al., 2012; Reference Shariff and NorenzayanShariff & Norenzayan, 2011). Particularly relevant are Laurin et al. (2012)’s finding that people who believed in supernatural control over events in the universe were less likely to sacrifice resources to punish norm transgressors. Our data demonstrate that such belief can also be accompanied with a reduced sense of personal responsibility to ameliorate human tragedy. This tradeoff in responsibility was exemplified in participants’ statements, such as “I don’t know that I feel comfortable intervening with the fate of these people. The natural course of the world will take care of itself. I choose to watch and feel poorly for those involved” and “It’s not up to me to play God. I don’t feel right deciding to end someone’s life, even if it’s saving someone else.” Such participants may take literally the biblical verse “It is I who bring both death and life” (Deuteronomy 32:39).

Notably, our findings point to a significant and consistent relationship between morality and the personal dimensions of religiosity, measuring personal devotion and private prayer. Religion’s more behavioral and social dimension, attending services, was not a robust predictor of deontological moral judgment – or consequentialist moral judgment for that matter – in any of our studies, not even on Sunday. This lack of connection suggests that the religious impact on moral judgment (at least in stylized moral dilemmas) is driven by personal rather than social religiosity. This is an interesting and somewhat surprising finding given previous investigations of the relationship between religion and prosocial behavior, which typically found that religious social behavior (often measured through service attendance) is more influential that religious belief and personal devotion. For example, Reference Ruffle and SosisRuffle & Sosis (2007) found that frequency of attendance predicted cooperative behavior in economic games and Reference Putnam and CampbellPutnam & Campbell (2012) found that participation in religious services, but not private prayer, predicted charitable giving and volunteering. Similarly, Bloom & Arikan (2013) found that priming religious attendance, but not religious belief, increased support for democracy. At the same time, service attendance was also related to intolerance and hostility towards outgroups, whereas private prayer was not (Reference Ginges, Hansen and NorenzayanGinges et al., 2009; Reference Putnam and CampbellPutnam & Campbell, 2012). Against this backdrop, which suggests that social behavior (good and bad) is more influenced by religion’s social practices, our findings suggest that moral judgment is more intimately related to personal religiosity – to devotion, belief, and private prayer. While it is unlikely that personal and social religiosity are completely detached, our study and others reveal that they might have different effects on judgment and behavior. This divergence is particularly interesting given that we commonly perceive prosocial behavior as tightly related to moral judgment and vice versa. An intriguing question for future research is whether different dimensions of religiosity mediate discrepancies between moral judgment and moral behavior. Future studies may also seek to map the precise role of religious attendance versus belief in judgments and behaviors which tap onto the same moral construct (for example judgments on cheating versus actual cheating behavior) to better understand these differences.

Finally, as compared to prior research that primarily focused on the moral judgment of North American Christian populations, we show that the relationship between deontological moral judgment and religiosity persists in Christianity and Judaism alike, despite their theological and cultural differences. This similarity may be due to the fact that both Christianity and Judaism are ordered around omniscient, interventionist gods. Previous research points to the many similarities in the structure and norms of societies that worship an all-encompassing, involved god (Roes & Raymond, 2003; Johnson, 2005). More specifically, both religions adhere to the belief that God commands humanity to follow certain moral rules (Judaism: Tractate Derech Eretz Zuta, Chapter 1, Talmud; Christianity: John 15:9–11, Luke 11:27–29, John 14:14–16) and both religions institute expansive rule-based normative systems, known as Jewish and Canon Law. Such normative systems, with their multitude of rules — that often focus on the nature of the action — are more likely to train adherents in deontological thinking style rather than apply utilitarian consequentialism, which calls for more flexible, case-specific, harm-benefit comparisons. This structural similarity is complemented by the existence of specific commands in both religions that support each of the deontological courses of (in)action in our studies. It is left to future research to examine the relationship between deontology, consequentialism and moral judgment in other religions.

Appendix: Religiosity measures

Please rate your agreement with the following statements from 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much):

-

• How strongly do you believe in God or gods?

-

• To what extent do you consider yourself religious?

-

• To what extent religion or faith are an important part of your life?

-

• To what extent do you identify with your religion?

-

• How often do you think about religion or being religious?

How often do you attend religious services?

1. Never

2. A few times a year

3. Once or twice a month

4. Almost every week

5. 2–3 times a week

6. Daily

7. Other _________ [textual answers written here were assigned one of the above values by the researchers or given an intermediate value. e.g., “4 times a week” was given a value of 5]

How often do you pray outside of religious services? [reverse coded]

1. Daily

2. 2–3 times a week

3. Once a week or less

4. Once a month or so

5. Only in times of need or emergency

6. Never

7. Other _________ [textual answers written here were assigned one of the above values by the researchers or given an intermediate value]

Regardless of your personal religious beliefs, which day of the week do you most closely associate with religious services?

[Used in Study 3 to exclude participants who do not affiliate Sunday with religion]

1. Saturday

2. Sunday

3. Monday

4. Tuesday

5. Wednesday

6. Thursday

7. Friday

8. I have never associated any day with religious services at any point in my life.