The escalation of environmental threats in Brazil is unprecedented in history. With science under attack and public institutions and policies being dismantled, destruction of the environment under the Jair Bolsonaro presidential administration is advancing at a rapid pace. Environmental degradation did not emerge under Bolsonaro: it dates from the first arrival of Europeans in Brazil and has continued over the centuries, with successive deforestation peaks. When President Jair Bolsonaro took office on 1 January 2019, his administration quickly became a threat to Brazilian forest ecosystems, native forest peoples and agricultural sustainability (Ferrante & Fearnside Reference Ferrante and Fearnside2019, Reference Ferrante and Fearnside2021a, Athayde et al. Reference Athayde, Fonseca, Araújo, Gallardo, Moretto and Sánches2022, Vale et al. Reference Vale, Berenguer, de Menezes, Viveiros de Castro, de Siqueira and Portela2021). Brazil could lose more than US$1 billion a year in agricultural production if deforestation in the Amazon is not contained (Leite-Filho et al. Reference Leite-Filho, Soarea-Filho, Davis, Abrahão and Börner2021).

The installation of the Bolsonaro administration was the culmination of a process of easing of the laws for deforestation and mining, which restarted in the 2000s. This process was consolidated in the Dilma Rousseff administration (2011–2016) and gained strength in the Michel Temer administration (2016–2018), despite the significant drop in deforestation achieved in the Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva government (2003–2011). Our objective is to report the sequence of events and federal government decisions that led to the worsening of the environmental situation in Brazil.

This process started immediately after President Bolsonaro took office, with various responsibilities of the Ministry of the Environment being transferred to other parts of the federal government, staff being dismissed, agreements with non-governmental organizations being suspended and environmental councils and committees being weakened or abolished (Brazil 2019b). There were even unsuccessful attempts to pervert the use of funds from international donations that had been received for projects intended to combat deforestation (Netto Reference Netto2019). The situation worsened, especially for the original peoples, when the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) was transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture with the aim of preventing new demarcations of Indigenous lands and validating invasions of existing Indigenous lands. FUNAI was returned to the Ministry of Justice in May 2019 by the National Congress, but President Bolsonaro’s appointment of a military police officer to head the agency and military officers to key positions within it ensured that his promise not to demarcate ‘a single centimetre of Indigenous land’ has been kept. These were setbacks and illegalities that have guided the Brazilian government’s anti-Indigenous policy (INESC 2022).

The federal government has systematically advanced the agenda of the ‘ruralists’ (large landholders and their representatives), both in legislative actions and in appointing ruralists to key positions throughout the government. The long list of setbacks includes constant interference in the inspection and control efforts of environmental agencies, the approval of 1682 new pesticides for use in Brazil from the beginning of the administration until June 2022 (many of them banned in Europe and North America; ROBOTOX 2022), cutting of government funds for environmental protection (Brazil 2019a, 2019d, 2020, 2021), weakening of the system for monitoring and combating environmental crimes (Bragança Reference Bragança2021), greatly reducing the application of fines (Brazil 2019c), criticism of forest research and monitoring agencies (Fearnside Reference Fearnside2019) and issuing decrees, ordinances and ‘provisional measures’ (executive orders valid for 120 days) that inhibit efforts to inspect for environmental violations and combat deforestation, burning, land invasion and illegal mining (ASCEMA 2020).

Bills currently advancing in the National Congress, demanded by the Bolsonaro administration, with strong support from members of congress aligned with ruralists and miners, would open up Indigenous lands for mining, dams and agribusiness (Villén-Pérez et al. Reference Villén-Pérez, Anaya-Valenzuela, da Cruz and Fearnside2022). These and other anti-environmental legislative initiatives have accelerated since the political turn of 1 February 2021, when, under the influence of the Planalto Palace (the official workplace of the president of Brazil), control over both houses of the National Congress passed to the ‘Centrão’ coalition of political parties, which support the ruralist agenda (Ferrante & Fearnside Reference Ferrante and Fearnside2021b).

At the 22 April 2021 climate meeting convened by US President Joe Biden, President Bolsonaro made promises such as ending illegal deforestation by 2030, but soon afterwards he took measures that favoured the legalization of deforestation and land claims (Fearnside Reference Fearnside2021b). The day after promising in his speech to double resources for the environment, President Bolsonaro published vetoes withdrawing R$240 million (US$46.7 million) from the Ministry of the Environment’s budget (Carneiro Reference Carneiro2021). Funds for the prevention of forest fires fell from R$49 million (US$9.4 million) in 2019 to R$37 million (US$7.1 million) in 2021. And in 2022 the President’s vetoes diverted R$8.6 million (US$1.8 million) from the Environment Ministry’s budget for promoting conservation and preventing fires (Menegassi Reference Menegassi2022). A bill (PL3729/2004), already approved in the Chamber of Deputies, will, when approved by the Senate, allow the self-licensing of infrastructure projects without analysis or judgement by the technical team of the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), the licensing body (Ruaro et al. Reference Ruaro, Ferrante and Fearnside2021). In October 2021, the Bolsonaro government approved cutting the federal budget for Brazilian science by more than 90%, further reducing the country’s ability to study and control deforestation (Kowaltowski Reference Kowaltowski2021).

Bolsonaro declined to attend the 26th Conference of the Parties to the Climate Convention (COP26) held in Glasgow (UK) in November 2021. Brazil’s representative at the conference changed the pledged date for ending illegal deforestation from 2030 to 2028, signed the declarations on forests and methane and stated that Brazil would achieve net zero emissions by 2050. However, there is no known plan to achieve these goals.

Part of the Amazon is already emitting more CO2 than it absorbs (Gatti et al. Reference Gatti, Basso, Miller, Gloor, Domingues and Cassol2021). Brazil is the world’s seventh largest carbon emitter. Reduced emissions from the sharp economic slowdown in Brazil resulting from COVID-19 were more than compensated by increased greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation in 2020. It is estimated that emissions grew by 10–20% in 2020 (SEEG 2020) because deforestation had not stopped, with strong government stimulus for the production and export of commodities.

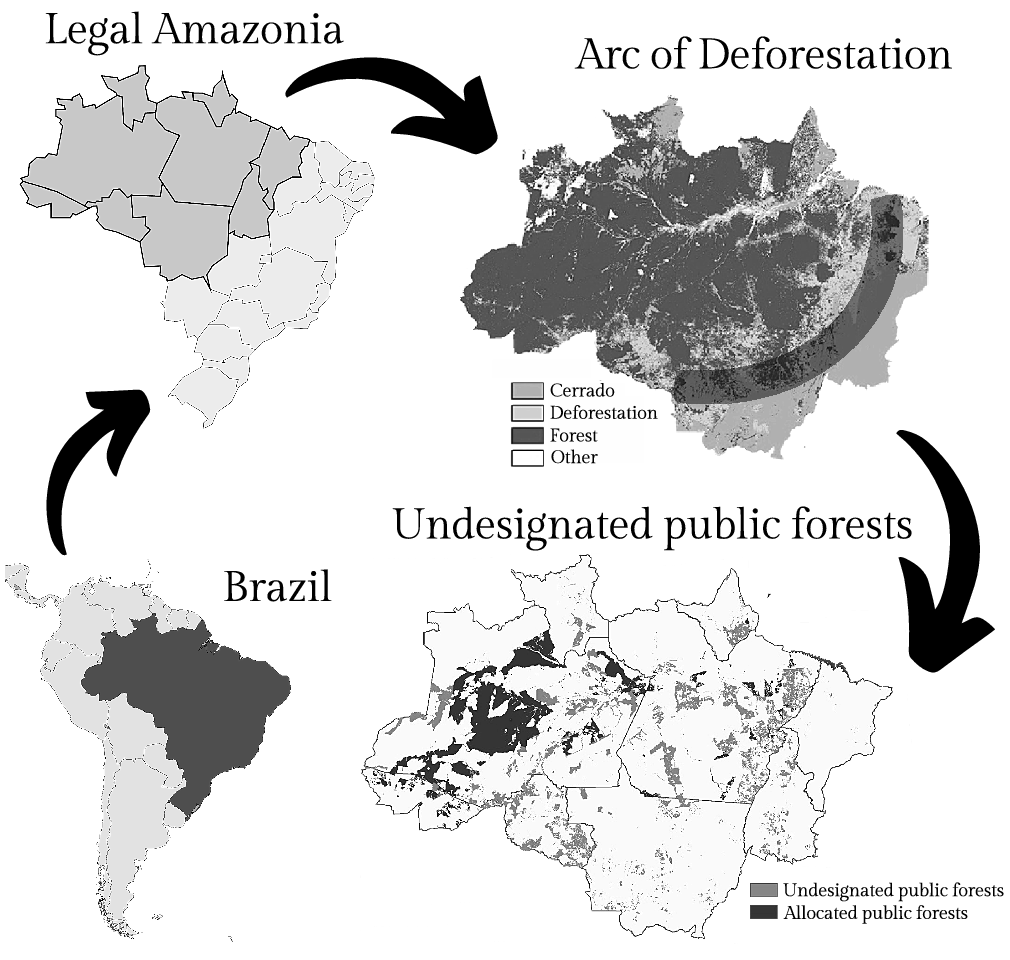

Deforestation in Brazil increased by 22% from August 2020 to July 2021 compared to the previous year. These deforestation data were available on 27 October 2021, but, by order of the President, these data were only officially released on 18 November 2021 so as not to contradict the administration’s speech at COP26 (Álvares Reference Álvares2021). This even-greater jump in deforestation reflects the effect of the government’s anti-environmental discourse, which sends a message that environmental crimes will always be forgiven. It also reflects the effect of the dismantling of environmental agencies, the budget cuts for these bodies and the many administrative measures that discourage or prevent the application of fines. Finally, it reflects squatters’ confidence in impunity if they invade and clear ‘undesignated public forests’ (government land that is not specified for use as a protected area or settlement project) since the ‘land-grabber’s law’ (PL2633/2020) was approved by the Chamber of Deputies in August 2021, while other bills are being processed in Congress that will further facilitate the legalization of illegally occupied areas (Ferrante et al. Reference Ferrante, Andrade and Fearnside2021). Encroachment on undesignated public forests (Fig. 1) emitted 1.87 billion tonnes of carbon between 2003 and 2019 (Kruid et al. Reference Kruid, Macedo, Gorelik, Walker, Moutinho and Brando2021).

Fig. 1. Progress in the deforestation and destruction of undesignated public forests.

This deforestation means that species are being lost, many of them before they have been described. The stock of global biodiversity is being significantly reduced and is heading towards mass extinction. Disrupting the integrity of ecosystems also affects human survival, as it reduces food production capacity (Flach et al. Reference Flach, Abrahão, Bryant, Scarabello, Soterroni and Ramos2021). Global warming may reduce water vapour in the air over Amazonia, leading to a reduction of 12% in the annual volume of rainfall, an effect that could reduce the availability of water for agriculture and livestock in the country (Sampaio et al. Reference Sampaio, Shimizu, Guimarães-Júnior, Alexandre, Guatura and Cardoso2021). These changes risk pushing the climate beyond its various tipping points (Walker Reference Walker2021). The destruction of forests in the Amazon, combined with climate change, could raise average maximum in-shade temperatures in the hottest month of the year in the region by up to 11.5°C, putting at risk nature, the economy and the lives of Amazonia’s residents (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Bottino, Nobre and Nobre2021).

The continuous litany of environmental setbacks in Brazil has enormous consequences for present and future generations, both in Brazil and in the world. This means that countries and international organizations around the world cannot simply watch this tragedy as mere spectators. One-fifth of the European Union’s soybean imports, produced in the Amazon and the Brazilian Cerrado, are linked to illegal deforestation (Rajão et al. Reference Rajão, Soares-Filho, Nunes, Börner, Machado and Assis2020). There are a variety of conditions that can be imposed on Brazilian international trade to induce change (Ferrante & Fearnside Reference Ferrante and Fearnside2021a), but the most likely to be effective would be restrictions imposed by importing countries (especially China) on Brazilian soy and beef produced in illegally deforested areas.

Acknowledgements

Our deep gratitude to the resistance of the native peoples, who fight in defense of the forest, at the cost of their lives.

Financial support

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

None.