Towards the end of 1920, in the aftershocks of the First World War, many felt that Australia was in need of cultural renewal. Henri Verbrugghen – the Belgian director of the New South Wales State Conservatorium – endeavoured to reinvigorate the Sydney musical scene through a campaign to promote what he considered to be a ‘local’ idiom: British music. Finding little success in acquiring funding or support for this idea in Sydney itself, Verbrugghen wrote to the president of the newly formed British Music Society (BMS) in London for advice. The ‘unexpected’ reply he received was that he had been unanimously appointed representative of the BMS for New South Wales.Footnote 1

While the name ‘British Music Society’ may appear parochial to a twenty-first-century reader – particularly in the context of 1920s settler-colonial Australia, which had two decades prior federated as a nation – the society's aspirations were international. The parent body of the BMS was established in the United Kingdom not only to champion British composers and musicians, but also to strengthen national musical appreciation by promoting all modern music and living composers, with nothing excluded, according to its founder, Arthur Eaglefield Hull, ‘so long as it is good music’.Footnote 2 Verbrugghen established a BMS branch in Sydney, expanding on these aims to specifically promote ‘Australian’ music as a category distinct from ‘British’, while the branch's overarching cosmopolitan outlook was made explicit when they changed their name to the ‘British and International Music Society’ in 1933 after affiliating with the International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM).

This article explores the activities of the British (later British and International) Music Society in Sydney, situating these within contemporary discourses of nationalism and internationalism in the construction of interwar Australian cultural identity. It argues that the sometimes conflicting aims of the BMS Sydney can be seen to reflect a wider political and social ambivalence about Australia's place in the post-First World War international landscape. As a fairly recently federated country, interwar Australians attempted to formulate their own identity in multiple ways, with some looking to maintain white Australia's cultural and social ties to Britain, while others believed Australia should seek to engage with the world beyond the confines of Empire. The Sydney BMS's primary goal, they asserted, was to champion local composers and assist in the development of a distinct Australian musical voice. However, this was held in uneasy balance with a desire to further the cause of British music ‘proper’ and to build a tradition of ‘international’ contemporary music in Australia.

The question of ‘Australian’ music within broader discourses of the national and the international is also closely interlinked with questions of aesthetics, and in particular, what ‘contemporary’ meant for music in Sydney at this time. Grounded in tropes of cultural insularity and a preoccupation with nationalism, general perceptions of this era suggest that interwar Australian culture was decidedly anti-modernist. However, as this article will demonstrate through the activities of the BMS in Sydney, the cultural nationalism of the era was not always isolationist, and many sought to explore the national in interaction with international aesthetic movements such as modernism. The British (and International) Music Society in Sydney, then, offers an important case study of the ways in which notions of the national and international, and modernism and anti-modernism were deeply entangled, as the society sought to explore and understand their shifting place in the world.

The British Music Society in Sydney

Shortly after Verbrugghen's unwitting appointment as the BMS representative, the Musical Association of NSW hosted an event to discuss the ‘Encouragement of British Music’.Footnote 3 Describing the ‘stimulus’ the formation of the BMS provided in England,Footnote 4 Verbrugghen asked, in his opening address, ‘what could be done to secure public support for British music, and to assist the Society at headquarters to extend its influence?’Footnote 5 Incorporated in London in 1919, the BMS headquarters aimed to promote British, increase public musical knowledge, and to establish a worldwide network of support for musicians and music-making.Footnote 6 To this end, branches were quickly established across the UK, particularly in the North of England and Northern Ireland, while further afield branches were also formed in Bangalore, Wellington, and Melbourne in addition to Sydney.Footnote 7 In the ensuing debate, at the Musical Association meeting, many members articulated their sympathy with the BMS's aims overall, but particularly demonstrated their interest in promoting Australian composition under this banner, and at the meeting's conclusion, the Sydney BMS branch was formally established.Footnote 8

The Sydney into which the BMS launched in 1920 was vibrant and prospering. Despite the lingering shadow of the war, the Spanish flu pandemic, and looming economic uncertainty, the city ‘entered the 1920s with optimism’.Footnote 9 Having grown to over a million inhabitants by the early part of the decade,Footnote 10 Sydney gradually replaced Melbourne as Australia's largest and most culturally dominant capital, transforming over the early twentieth century into a cosmopolitan metropolis.Footnote 11 With its prominent harbour, it was a major node in an international trade and communication network; a ‘port of call in the ceaseless international ebb and flow of commerce and ideas that underpinned cosmopolitan modernity’.Footnote 12 The First Nations population of the area had been subjected to over a century of forced removal as part of a larger process of genocide and dispossession. This left the Sydney population mostly Australian-born, of British and Irish ancestry, as government-implemented ‘spatial segregation’ removed First Nations people to reserves and communities on the outskirts of the city, such as La Perouse on Botany Bay or Salt Pan Creek in Western Sydney.Footnote 13 The population of Sydney was further supplemented with the arrival of every new ship, which brought additional tourists, itinerant workers, and permanent migrants from across the world.Footnote 14 Sydney's inhabitants were broadly educated, and had a fairly uniform distribution of wealth, meaning that entertainment, technology, and cultural activities were widely accessible.Footnote 15 Accompanying a boom in new forms of entertainment such as cinema and the gramophone, the early twentieth century saw the flourishing of many Sydney cultural institutions. The first iteration of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra was founded in 1908, the Conservatorium established in 1915, the State Orchestra was founded the following year, as was the Australian Music Examinations Board in 1918.Footnote 16

It was from this cultural milieu, with its community of committed musical advocates that, in early November 1920, the first Sydney BMS committee was elected. Verbrugghen remained the society's honorary representative, reporting directly to headquarters in London. Described by Diane Collins as ‘a considerable egotist’, and with a glittering European career as a virtuoso violinist, orchestral player, and conductor, Verbrugghen had accepted the position as inaugural director of the NSW State Conservatorium ‘at the very moment’ his career ‘seemed about to catapult him into much greater prominence’.Footnote 17 He was introduced by the Sydney Morning Herald in 1915 as ‘A Man of Large Ideas’,Footnote 18 and his tenure in Sydney was distinguished by a commitment to new music, determination to create ‘intelligent and informed listeners’, and an artistic identity founded on ‘the importance of nation’.Footnote 19 With his personal aims mirroring those of his BMS branch, the respect he garnered in Sydney further increased the standing of the branch itself. The rest of the inaugural committee were prominent local musical figures. Melbourne-born composer, conductor, and violinist Alfred Hill was elected president; organist and choral director George Faunce Allman was appointed treasurer; while Wilfred Arlom, a pianist and flautist – and Australia's first subscribing member of the BMS, having joined the parent body at its founding – became librarian and secretary (he would also become the BMS representative when Verbrugghen left Australia the following year, and the ISCM Australian Section secretary from 1927 to 1939).Footnote 20 Arthur Benjamin, Roland Foster, Frank Hutchens, William Arundel Orchard, Esther Kahn, and Mirrie Solomon made up the general committee.

The newly formed Sydney BMS immediately set to work proselytizing for British music. Their first concert, given at the Conservatorium in December 1920, was described as ‘an all-British programme’ and attracted a large audience that Verbrugghen hoped would ‘listen to the moderns in a receptive frame of mind’.Footnote 21 As a critic in the Daily Telegraph noted, ‘British’ was taken here ‘to mean the whole Empire’, with Australian composers dominating the programme.Footnote 22 The concert opened with a piano and violin sonata by Benjamin, described as ‘most acceptable at a first hearing’, being not ‘ultra-modern in idiom’.Footnote 23 This was followed by a group of songs by Lindley Evans, and Kahn's Three Seventeenth Century Dances, considered ‘especially captivating’.Footnote 24 The most highly praised work was Hill's Impression for Voice, String Quartet, and Piano, which portrays nuances of the Australian landscape from the ‘shimmering heat haze’ to the ‘coming of the southerly’. As a Sunday Times critic concluded, Australians should be proud to have produced ‘a genius capable of creating so essentially Australian an atmosphere’.Footnote 25 The ‘British works proper’ were Frank Bridge's Londonderry Air quartet, which Verbrugghen introduced as containing ‘one of the loveliest airs in existence’, and a piano quartet by Herbert Howells. The Howells received a more subdued reception, as its ‘modern idiom’, after two hours of continuous music, was considered ‘debilitating to all but a few exceptionally robust musical constitutions’.Footnote 26

This first programme emphasized contemporary music from both Australia and ‘Britain proper’, but from 1921, contemporary music from wider Europe began to appear on BMS bills. With the news that headquarters had become the British section of the ISCM in 1922, in early 1923, the Sydney branch followed this lead, deciding to also champion ‘interesting music of foreign origin’.Footnote 27 The proportion of ‘foreign’ music steadily increased, and by the 1930s programmes were generally half Australian or British, and half ‘Continental’ music. In 1927, the society received its formal notice of affiliation with the ISCM, prompting further interest in ‘international’ contemporary music at home, while pursuing the promotion of contemporary Australian music abroad.Footnote 28

The BMS Sydney was managed by a committee of up to twelve members, plus a president, secretary, treasurer, librarian, representative to the BMS (and later ISCM), and for a time, an official accompanist. Apart from Kahn and Solomon on the inaugural committee, and Gertrude Barton the pianist – and principal of the Dilbhur Hall finishing school for girls – acting as secretary from 1925, the Committee of Management was controlled exclusively by men. This remained the case until a ‘very heated’ annual general meeting of 1927 addressed the question of opening committee roles to women. Pianist and composer Frank Hutchens ‘quite opposed the suggestion’, arguing that ‘men had managed’ well enough and that ‘things would be happiest’ if they remained the same. Gladys Marks, a lecturer in French, and the first female professor at the University of Sydney, delegate to the Australian Federation of University Women, and vice president of the National Council of Women – who seems to have attended the meeting specifically for this debate – pointed out ‘in very eloquent terms’ that women ‘had proved that their work in every way was quite as brilliant as the men’. Put to a vote, the motion ‘passed amid great applause’,Footnote 29 paving the way for pianist and renowned teacher Winifred Burston to be elected president in 1934.Footnote 30 Gender-balance continued to be a surprisingly common topic in the BMS Sydney's discussions, with a committee membership quota of 50% women introduced in 1928,Footnote 31 and ongoing efforts to represent women composers on their programmes.

As the branch developed, their activities became more extensive. Five to six major concerts were held each year. These were mostly chamber recitals, but orchestral programmes were also possible in the early 1920s through Verbrugghen's association with the NSW State Orchestra and his direct successor at the Orchestra and Conservatorium, William Arundel Orchard, who became the BMS's second president. This led to Australian premieres of many major orchestral works, including by Granville Bantock, Samuel Coleridge Taylor, Hubert Parry, and Edward Elgar.Footnote 32 The society cultivated relationships with radio producers after public broadcasting began, presenting programmes on both local stations 2FC and 2BL. They established a lending library, funded by ticket sales to non-members, which grew from around 300 scores to over 1,000 in the first two years. A further highlight of the BMS calendar was an annual conversazione, held in conjunction with the Royal Art Society's annual exhibition.Footnote 33 Education was also central to the BMS's activities. They hosted monthly evenings where ‘new and little known pieces’ acquired by the library were demonstrated to music teachers.Footnote 34 From the early 1930s, local schools could arrange for society-affiliated performers to give concerts to their students. From 1927, students of schools that affiliated with the BMS were also able to participate in a large annual competition in solo and ensemble performance.

Throughout these activities, the Sydney BMS focused firmly on ‘contemporary’ music. But what was meant by ‘contemporary’ in this context? While this ‘highly malleable’ term has been variously defined through periodization or reference to specific aesthetic techniques, as Sarah Collins has demonstrated, for the ISCM, there was much uncertainty surrounding the multiple ways this term could be mobilized to political and artistic ends.Footnote 35 Debates through the 1920s and 1930s about whether the ISCM would ‘support all forms of music composed recently’, or favour ‘progressive music’ remained unresolved.Footnote 36 While Edward Dent argued in the society's 1923 objectives that it intended to pursue ‘groundbreaking trends in music’, what these actually were differed between countries and time periods.Footnote 37 The Sydney BMS, in contrast, showed little anxiety about defining the ‘contemporary’, even after affiliating with the ISCM. It was only when asked by the local Association of Headmistresses to clarify what was meant by ‘British or Foreign Contemporary’ in the students’ ‘own choice’ section of the schools competition, that a definition was provided.Footnote 38 After a short discussion, the committee decided that ‘contemporary’ simply referred to ‘living composers and those who have died within the ten years preceding’.Footnote 39 While the Sydney branch did align themselves with one of Dent's aims for the ISCM – to ‘create support for a continuing community of composers’ – they did so through a distinctly national framework, demonstrating a broader contemporary Australian preoccupation with defining the national.Footnote 40

Britishness and ‘National’ Music in Interwar Australia

At the initial meeting to establish a BMS branch, Verbrugghen argued that it was the Musical Association's ‘duty’ to support the idea and ‘further a movement which was national in its appeal’.Footnote 41 By these comments it is clear that Verbrugghen's idea of British music encompassed music made in Australia. While this may appear strange today, at the time, British and Australian were neither politically, nor socially, nor culturally the mutually exclusive terms they are today.Footnote 42 Verbrugghen's promotion of ‘British’ music as a ‘national’ movement within Australia reflects a contemporary ambivalence in Australian self-perception and identity, and illustrates an ongoing conflict in Australia's relationship with Britain as a political and cultural concept.

While some historiographies of Australia describe the country's separation from Britain through a teleological lens of struggle towards independent sovereignty, Neville Meaney has influentially argued that Britishness formed a fundamental part of early twentieth-century Australian identity.Footnote 43 Although the 1901 Federation of the Australian colonies created the singular political entity of Australia, the devolution of the administrative relationship with Britain was more prolonged. It was not until 1949, with the Nationality and Citizenship Act, that an ‘autonomous nationality’ was conceived; however, Australians remained legally required to declare their nationality as British until 1969, and it was 1984 before they ceased to be considered British subjects.Footnote 44 Federation itself was imagined as a triumph of ‘democracy rather than independence’ and Federalism regarded as ‘a natural outcome of British culture’, with the ‘invisible links’ that tied Australia to Britain preserved through the Commonwealth, facilitating ‘an enduring or even increasing loyalty to the Motherland’.Footnote 45 Throughout the twentieth-century, Australia's engagement with the world was often mediated through established imperial networks, while restrictive immigration policies curtailed non-European immigration and promoted a white, British, mono-ethnic state.Footnote 46

Race played a particularly strong role in the formation of early twentieth-century Australian identity. As the product of settler colonialism,Footnote 47 Australian society was founded on genocide and the dispossession of First Nations peoples from their cultures and land to facilitate the mass settlement of white colonists. At the same time, much of the early twentieth-century nation-building discourse engaged in a systemic ‘writing out’ of Indigenous voices and people.Footnote 48 Despite an active First Nations civil rights movement across the 1920s and 1930s,Footnote 49 both official policy and social life forcefully isolated Indigenous people from the white population. For the settler community, then, in racial terms, whiteness was foundational for national identity, and in this sense Britain provided what Jim Berryman describes as an ‘idea of a homogeneous ethnic and cultural community’.Footnote 50 The racial homogeneity promoted in Australia did not, however, reflect the actual make up of Britain. Disparate ethnic and regional identities from of across the British Isles (including the Irish who ‘against their will, were designated “British”’) in this transplanted context were amalgamated into an overarching ‘Britishness’ that did not exist anywhere in Britain.Footnote 51 White Australians, therefore, could feel a strong attachment and identification with ‘Britishness’ or the Empire as a singular entity, unaffected by regional distinction or their own individual backgrounds.

That the BMS Sydney identified with this sense of overarching Britishness is perhaps self-evident, but it is reinforced by their actions, particularly at times when such an identity was challenged. At several points it was suggested that the branch change their name, alter their governance, or shift their focus in a way that de-emphasized ‘Britishness’. In 1927, for instance, it was proposed that the BMS merge with the Musical Association, as the two organizations’ aims and membership ‘rather overlapped somewhat’.Footnote 52 Proponents of the idea were largely those active on both committees, suggesting that an amalgamation might ‘save the members from attending too many meetings’, and that joint concerts and lectures ‘would be more fully attended’. In general, however, this proposal was objected to in the strongest terms. At a meeting discussing the idea, violinist Stephen Vost Janssen argued that ‘the BMS was an empire body and that Sydney should have its centre’. Organist and teacher Edwin J. Robinson stated that ‘he did not approve of any affiliations that would cause the BMS to lose its identity as an empire concern’, while Barton as secretary ‘opposed any scheme that would … see the BMS lose its identity as a Home Centre’.Footnote 53 The proposal was rejected, and the vehement response to it demonstrates the stake members held in retaining a tangible link to Britain.

It is also clear that the BMS Sydney considered music by ‘Australian’ composers – that is, either Australian-born or long-term resident – to be writing unproblematically ‘British’ music. While they rarely presented concerts of solely ‘British’ work, even those few that did usually included at least one piece by an Australian composer. In May 1932, for instance, a concert of ‘British Works’ at the Forum Club by Cyril Monk and Lindley Evans contained York Bowen's Suite for Violin and Piano, solo piano and violin works by Howells and Herbert Hughes, and further solo pieces by Australians Hill, Benjamin, and Hutchens (as well as, inexplicably, a trio by Anton Arensky featuring cellist Osric Fyfe).Footnote 54 A similar concert in August 1939 billed as containing only ‘British Works’ in fact featured only one non-Australian composer in a violin and piano sonata by Muriel Talbot Hodge, which was accompanied by songs by Hazel King, a set of ‘Tudor’ songs arranged by Alex Burnard, and violin solos composed by Marjorie Hesse and Hutchens.Footnote 55

The ‘British’ programmes that contained no Australian works tended to be historical in focus, such as in two concerts of English madrigals – the first in 1922 with a lecture by Orchard, and the second in 1937 accompanying a talk by visiting Tudor specialist Richard Terry – or in another that confusingly celebrated ‘the Anniversary of the Birth of Henry Purcell’ more than two months after his 272th birthday on 23 November 1931.Footnote 56 These events were generally regarded as being important for their educational content, providing an illustration of what was considered a shared history. Settler Australia at this time suffered from what James Gore describes as a ‘limited sense of national and historical consciousness’ – ignoring the continent's more than 60,000 years of First Nations history – meaning that maintaining ties to Britain also provided a sense of historical continuity with the ‘old world’.Footnote 57

While much of the BMS Sydney's activities in the promotion of ‘British’ music might be considered benign expressions of latent cultural identity, in some cases they manifested as explicit xenophobia. For example, in late 1928, Margaret Chalmers – the BMS official accompanist – resigned from the society due to comments made by Gertrude Barton about her accompanying visiting Russian singer Vladimir Elin. Barton had apparently refused to be introduced to Elin, and suggested Chalmers was being ‘disloyal’ and should be ‘ashamed to be playing’ with him.Footnote 58 Barton refused to retract her comments, arguing that she would not consider doing do ‘while her country is suffering such industrial oppression’. There was an ‘implacable antagonism towards the Soviet Union’ in Australia at this time, with the government and large parts of the media being openly hostile to the Bolsheviks following their withdrawal from the First World War.Footnote 59 Elin was evidently not a Bolshevik, reportedly fleeing Russia at the Revolution, and moving to a teaching post in the Philippines via China, but his visit seems to have prompted hostility regardless.Footnote 60 Though there was a small amount of dissent, it was Barton, not Chalmers, supported by the Society, and long-time member Roland Foster who proposed a new singing competition based on British works in the wake of this argument, as a means of reiterating the branch's support for their ‘own artists’.Footnote 61

Australian Music in and for Australia

Despite the connection of shared history and strong links to Britain embodied through their ‘ethnic’ identity, early twentieth-century settler Australians also developed a distinct sense of ‘Australianness’. This has been termed a ‘civic’ identity, described by Russell McGregor as encompassing aspects of Australian society deemed unique, particularly in distinction from Britain (for instance, a sense of egalitarianism in opposition to the British class system). This allowed Australia to promote its own geopolitical interests, separate from the United Kingdom, but it also ‘stirred the deepest nationalist passions’ as expressed through art, from which Australia could begin to develop its own cultural forms, including – in music – attempts to define an Australian compositional voice.Footnote 62

The interwar period was particularly fruitful in this respect. Australia had been isolated from Europe during the First World War, accepted at the time as necessary to protect the ‘young’ country from the ‘morbidity and decadence of the old world’; however, by the end of the 1920s, this isolation came to be considered the cause of a national ‘backwardness, insulation and lack of sophistication’.Footnote 63 At the same time, traditional national symbols of earlier colonial identities, such as the ‘the rural pioneer and heroic digger’ began to lose their efficacy, coming instead to represent ‘the unthinking patriotism’ that had sent so many to their deaths.Footnote 64 Amongst these shifting cultural dynamics, Australians began to champion a new self-conception of energetic industrial progress and independent ‘cultural maturity’ alongside a growing rejection of blind imperial loyalty.Footnote 65 In the arts, this spurred a growing and ‘intense concern’ with the ‘national theme’,Footnote 66 and it was in this context that the championing of ‘Australian’ music – as distinct from ‘British’ – formed a key goal of the BMS Sydney. While Australian works often appeared on ‘British’ programmes, the society also regularly presented all-Australian concerts. The first of these was a lecture-concert given by Verbrugghen in June 1921, containing works by Roy Agnew, Arthur Benjamin, Hooper Brewster-Jones, Dulcie Cohen, and Fritz Hart.Footnote 67 From then on two to three concerts per year focused solely on Australian works, often becoming the most well-attended and successful performances of the season.Footnote 68

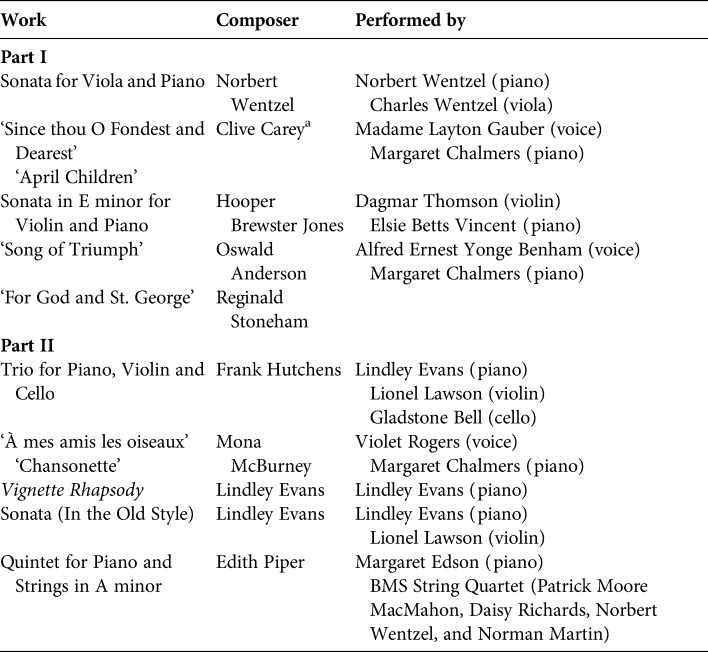

The period of 1926 to 1932 saw a particularly heavy engagement with Australian works: as the Sydney Morning Herald reported in 1927, the ‘zealous activities of the British Music Society’ provided Australian composers with ‘frequent opportunities of hearing their music’ and ‘furnished’ audiences ‘with the chance of learning something of the productive artistic enterprise of its own country’.Footnote 69 While there were occasionally works sought from other states – for example, Brewster Jones in Adelaide or Hart in Melbourne – the majority of these programmes contained compositions by Sydney branch members. Tables 1 and 2 show examples of such programmes from this period.

Table 1 British Music Society (Sydney Branch) Concert of Australian Works, Adyar Hall, Bligh St, Sydney. Monday, 25 October 1926

Source: ‘Advertising’, Sun, 24 October 1926, 39.

a Clive Carey – usually considered a British composer – had been director of the Elder Conservatorium, University of Adelaide from 1924 and was here an ‘adopted’ Australian.

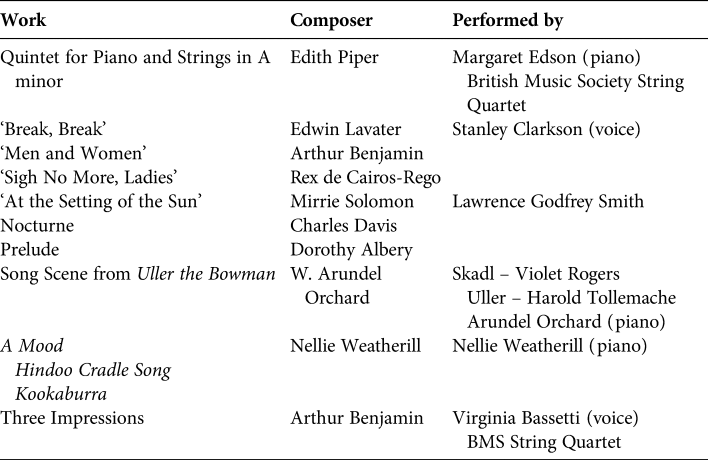

Table 2 British Music Society (Sydney Branch) Concert of Australian Compositions, Conservatorium Hall, Sydney. Tuesday, 20 September 1927

Source: ‘Advertising’, Daily Telegraph, 20 September 1927, 13.

The Sydney BMS also made efforts beyond their regular concert calendar to promote Australian music. Their annual conversazione with the Royal Society of Art was seen as a forum for the presentation of Australian cultural achievements, with programmes from 1924 to 1928 all containing only works by Australian composers, experienced alongside ‘Australian efforts in the sister art’.Footnote 70 Equally, when distinguished international guests were hosted by the society, a programme of Australian works was usually given. For example, when Hugh Allen – president of the Royal College of Music in London, and associated with BMS headquarters – visited Sydney in 1930, the reception included a short concert of Hill's ‘Maori’ Quartet, a group of songs by Solomon, and piano works by Agnew.Footnote 71

Any presentation of music as ‘Australian’ at this time provoked debate about its content. The first all-Australian BMS programme in 1921 elicited much ‘confusion of ideas’, according to the journal Musical Australia, as to whether the BMS intended ‘Australian’ music to be viewed as an aesthetic category, or simply as ‘emanations from composers who are Australian’. They concluded that it could ‘hardly be contended that there was anything distinctly Australian’ about any of the works, because it was ‘exceedingly doubtful if Australian musical characteristics are as yet sufficiently developed to be recognisable’.Footnote 72 While the question of what might constitute a distinct Australian compositional voice had been pursued since the nineteenth century, these discussions reached a new peak in the interwar period, and beyond the BMS's activities, articles in the press and letters to the editor regularly debated the concept of Australian music. Organizations such as the ABC, established in 1932, placed developing the nation's ‘cultural musical life’Footnote 73 and laying ‘the foundation of an essentially national musical literature’Footnote 74 at the core of their activities, and they pursed an explicit ‘national style agenda’ reflected in their programming, establishment of state-based orchestras, and sponsorship of composition competitions.Footnote 75

Despite an apparent consensus on the need to develop an Australian music, there was little agreement on what this might sound like, and how it might differ from the European techniques that formed the basis of compositional training in Australia. The landscape was often cited as a profitable starting point. Landscape was an important element in the representation of Australia in literature and visual art, and is equally common to musical constructions of nation across the world – as Carl Dahlhaus explains, ‘musical landscape is among the permanent components of a national musical style’.Footnote 76 From the early twentieth century, a number of composers attempted to evoke the Australian landscape, from onomatopoeia and tone painting of the sounds of the bush as in Hill's works described earlier, to composers such as Hart who – while working in a European idiom – sought to illustrate a more abstract ‘spirit of the country, “its bushland, its hills, its delicate shades in landscape, colour, life, everything”’.Footnote 77 Prompted by the BMS's invitation to local composers to forward their manuscripts for consideration on upcoming programmes, George de Cairos Rego – critic and father of future BMS treasurer Rex de Cairos Rego – published an extended Daily Telegraph piece in 1922, asking what ‘characteristics of Australian music’ the BMS might expect to receive. In de Cairos Rego's opinion, engaging with the unique Australian landscape would be fundamental to creating an Australian music, but he also argued that a composer from Sydney could not be inspired to the same extent as one from the NSW South Coast, with the ‘wonderful panorama of land, sea, and sky’.Footnote 78 As de Cairos Rego concluded, ‘the painter has a way of transmitting the spirit of these scenes to his canvas, but so can the musician, with the abundant resources of his tone-art’.Footnote 79

Together with questions of landscape, the idea of folk song – and particularly, the lack of an Australian folk tradition – also frequently entered into these discussions. In 1924, the BMS's president J. Hugh McMenamin gave a lecture on music education, describing what he considered the difficultly of creating an Australian tradition when ‘Australia has no folk music; it is no land of legend; it has no musical past … the Australian people as a people are songless’.Footnote 80 This argument appeared often in contemporary discourse on Australian music, with Cyril Monk, another erstwhile BMS president, writing in the later 1930s that Australians did not lack talent or taste, but simply worked ‘under the handicap of lack of tradition’.Footnote 81 Where European composers could mine centuries of musical development and folk music for inspiration, Australians could look only to recent history or models from other nations, hampering their creation of something unique. In a further lecture of June 1926, McMenamin reiterated his point, arguing that ‘Australian composers were still under the discipleship of European methods’ as they had ‘no primitive Australian music to work on’.Footnote 82

In both of these lectures, McMenamin suggested that engaging with Indigenous music for this purpose would be fruitless, with ‘the aborigines being singularly devoid of any musical instinct’.Footnote 83 This was one of the very few times that the BMS acknowledged the existence of a First Nations musical tradition, but also speaks to a wider contemporary debate about the incorporation of Indigenous materials into European art music in service to building a uniquely ‘Australian’ sound. Many writers and musicians of the period agreed with McMenamin: Andrew MacCunn, director of J. C. Williamson, for example, argued that Indigenous music possessed ‘distinctive rhythm, but no melody’, making it unsuitable for adaption.Footnote 84 Others, however, maintained that ‘the only way Australian music can ever be really Australian is by adopting aboriginal ideas and themes’.Footnote 85 Composer, theosophist, poet, and early broadcaster Phyllis CampbellFootnote 86 argued, for example, in an article called ‘Nationalism in Australian Music’ for the 1928 pamphlet Advance! Australia!, that like the United States, Australia might develop its own music through a combination of ‘importing European art and music’ and white composers being ‘inspired by native music, Aboriginal songs and legends’.Footnote 87

There were indeed a number of settler composers in the 1920s and 1930s who attempted to integrate references to First Peoples musics into their works.Footnote 88 These efforts once again paralleled movements in visual arts in literature, such the Jindyworobaks whose ‘expression of artistic nationalism’ combined European cultural idioms with evocations of landscape and Aboriginal imagery, or the modernist painters whose ‘nationalist aesthetic’ appropriated Aboriginal cultural property.Footnote 89 Yet across all of these forms, as Amanda Harris argues, these discussions were ‘fundamentally self-referential’, using materials from non-Indigenous ethnographers and anthropologists to claim ‘authority to speak on Aboriginality and Australian identity’ to the explicit exclusion of Aboriginal people.Footnote 90 For the BMS, these issues appear to have been considered peripheral to their construction of Australian music, and discussion of Indigenous music – when it occurred at all – was always framed through its relative value as a tool for white composers to use.

Internationalism and ‘International’ Music

When the BMS's London headquarters closed in 1933, the Sydney branch was left with a question over their identity. Without the parent body, the branch lost the symbolic ties to Empire that had legitimized their activities. The initial reaction from some members was simply to continue as they were – as many BMS branches across the UK and world did – other members argued for a shift in focus, continuing as the Australian Section of the ISCM only.Footnote 91 After several months of fruitless discussion the branch settled on a compromise: they changed their name to ‘The British and International Music Society’, ‘but the full description of the ISCM [was] to be placed on notepaper and programmes’.Footnote 92 While the ‘international’ had been an important consideration for the BMS Sydney from their inception, their new name gave this aspect stronger emphasis. An article placed in the Sydney Morning Herald by the committee stated that the closure of headquarters was an ‘opportunity’ allowing the branch to restructure ‘along new lines’ and noting that they had previously been subject to criticism for being called the ‘British Music Society’ while presenting ‘a good deal of music of other nationalities’.Footnote 93

This ‘criticism’ and the broader question of where the ‘international’ fit within the activities of a body whose name implied a ‘national’ focus reflects a wider conversation occurring across multiple levels of Australian society. Although interwar Australian identity had been primarily shaped by the historical relationship with Britain, from its colonial beginnings, Australia had always been part of a wider international network of communication.Footnote 94 Major cities such as Sydney were in constant interaction with the world, and the society – while not necessarily multicultural – was outward-looking, cosmopolitan, and ‘embedded in international exchange’.Footnote 95 An increasing ‘internationalist zeal’ emerged following the First World War, further shifting the dynamics of Australia's relationship with both the British Empire and the world beyond its confines.Footnote 96

Like Britishness and Australianness, internationalism and nationalism were not mutually exclusive categories, but rather deeply entangled ‘complementary features’ of Australian politics in this era.Footnote 97 As Glenda Sluga has observed, internationalism and nationalism, and the ‘knowledge that shaped them’ in the early twentieth century, were ‘twinned liberal ideologies’ that stemmed from ‘questions surrounding modernity, democracy and progress’.Footnote 98 The war had certainly heightened the sense of national identity, but growing awareness of Australia's place in the Pacific and the ‘accelerating pressures of mobility, communication and consumption’ also saw Australia commit to a number of internationalist initiatives, simultaneously maintaining a sense of nationhood and a growing ‘international consciousness’.Footnote 99

The end of the First World War had seen Australia take a stronger role in international discussions, acquiring ‘special dominion’ status at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, which placed it, as Nicholas Brown argues, ‘within the compass of the British Empire but with enhanced capacities for independent state action’.Footnote 100 On this stage, Prime Minister William ‘Billy’ Hughes brought demands for ‘Carthaginian peace’ and punishment of Germany, opposition to the United States's ambition for liberal internationalism, rejection of a declaration of racial equality proposed by Japan, and an ‘insistence that Australia retain control of New Guinea’ that ‘importuned the British’.Footnote 101 This nationalistic chauvinism was also reflected in many of Australia's domestic policies, such as the exclusionary implementation of what has been commonly (though never officially) termed the White Australia Policy (WAP).Footnote 102

While the ‘jingoistic patriotism’ of Hughes and the isolationist WAP had support at home, they occurred in seemingly contradictory interaction with a growing interest in internationalism.Footnote 103 With acknowledgement of Australia's geographic interests in the Pacific, Hughes himself – and as reflected in broader public opinion – saw the era as ripe for both racial ‘competition’ and ‘cooperation’.Footnote 104 Non-government internationalist organizations flourished in Sydney, with the League of Nations Union and the local branch of the London Peace Society among the most prominent;Footnote 105 at the same time, pre-war internationalist philanthropic programmes (such as the Carnegie Corporation and Rockefeller Foundation) continued to grow in influence.Footnote 106 While many of these organizations were established with peace and security in mind, others were concerned with civic education, or the labour and women's rights movements, while others still represented the cultural sphere.Footnote 107 In this sense, the BIMS was part of a prospering movement of ‘institutionalised internationalisation’.Footnote 108

In the arts – and music especially – the interwar period is sometimes characterized as Australia's ‘dullest’ or ‘driest’; however, much recent scholarship has demonstrated that it was indeed ‘cosmopolitan, vibrant, and modernizing’.Footnote 109 While the same anti-internationalist ideas that characterized the WAP also led to censorship of imported ‘obscene’ and ‘subversive’ literature, hindering the dissemination of European modernism, there remained ‘signs of a wider cultural life’, from touring international artists, to the influence of European refugees, and by the 1930s commercial sponsorship of modernist art.Footnote 110 In music, the BIMS was just one organization engaging with the international. Other examples might include the radio broadcasts of Brewster-Jones, described by Kate Bowan as ‘ground-breaking’ for their breadth of programming,Footnote 111 or Percy Grainger's ABC lectures, which saw ‘the universality of music’ as a ‘unifying theme’.Footnote 112

For the BIMS, ‘international’ music had been central to their activities throughout their existence. Early concert programmes often featured a work or two by European composers – with Karol Szymanowski, Maurice Ravel, and composers of Les Six among the most frequently heard – with occasional reference to music from the United States. The first major programme to take an ‘international’ theme, however, was a June 1927 concert given to celebrate the branch's affiliation with the ISCM. Held at the Sydney Conservatorium and broadcast on 2FC, the programme was a whirlwind tour of European music, with each work clearly delineated on the printed programme by its composer's country of origin (Figure 1).Footnote 113 Beginning with a set from Britain by Eugene Goossens and Arnold Bax, this was followed by Szymanowski as a representative of Poland, a bracket of French and ‘Russian’ songs by Ravel and Léon Guller (the ‘Russian’ here perhaps relating to the influence of Russian music and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade on Ravel), further French music by Darius Milhaud, and a Hungarian work by Béla Bartók.

Figure 1 Programme of Compositions by Modern Contemporary Composers, British Music Society (Sydney Centre), 14 June 1927. Arlom Family Papers 1884–1955, State Library of NSW, MLMSS 7955 3 (5).

From the 1930s, programmes generally consisted of half British or Australian music, and half ‘international’. Sometimes the ‘international’ section would offer a mix of pieces from around the world, as in a programme of 21 October 1932 which combined ‘Old English’ and contemporary songs by Bax and Peter Warlock with French violin works by François Couperin and Jean Baptiste Senaillé, and ‘international’ contemporary music by Isaac Albeniz, Ernest Bloch, Igor Stravinsky, Francis Poulenc, and Manuel De Falla.Footnote 114 Some programmes highlighted a particular composer, as in a 1937 presentation of ‘Songs about Love’ and ‘Songs about Death’ by Finnish composer Yrjo Kilpinen,Footnote 115 or a ‘Memorial Concert’ of 30 June 1938 for Ravel and Albert Roussel, both of whom had died the previous year.Footnote 116 Other programmes focused on a particular country or region, as in a June 1934 concert which presented works by Elgar, Hughes, and Bridge alongside songs by Alexander Borodin, Mily Balakirev, Alexander Gretchaninoff, and Rimsky-Korsakov (sung by Ruth Ladd), and piano works by Alexander Scriabin, Sergei Prokofiev, and Nikolai Medtner, performed by Russian pianist Alexander Sverjensky who had settled in Sydney in 1925.Footnote 117 Maintaining their focus on education as the BIMS, illustrated lectures also continued to be offered throughout the 1930s, with Lucas Staehelin delivering two talks – the first on Swiss composers Arthur Honegger and Conrad Beck in October 1935, and the second on Paul Hindemith in November 1936 – as well-received examples. Staehelin had been a member of the ISCM Basel before migrating to Sydney to marry an Australian woman, supposedly yodelling ‘across the water to his fiancee’ as soon as his ship was within earshot.Footnote 118 He replaced Arlom (on Arlom's recommendation) as Sydney's ISCM representative in 1939.Footnote 119

Much of the contemporary music performed by the BIMS was sourced through local music retailers, particularly W. H. Paling & Co.Footnote 120 In the 1930s, however, the BIMS also actively sought new music directly from other ISCM centres, with Arlom procuring scores from centres in Austria, Argentina, Cuba, and the Netherlands.Footnote 121 Through this, in July 1934, audiences heard works from Vienna sent by Paul Pisk – one of the ISCM's founding members – including music by Egon Kornauth, Alban Berg, and Joseph Marx. Although there was great interest in the Australian premiere of these works, their reception was mixed, with Kornauth's Op. 26 String Quartet considered ‘deeply felt and beautiful’ but Berg's piano sonata regarded as ‘not particularly interesting’.Footnote 122 A further package of music was reportedly received from Giullame Landre in the Netherlands, but no Dutch music seems to have made it onto concert or radio programmes. Cuban music, however, appeared several times. In particular, a piano sonata by Joaquín Nin-Culmell was broadcast in February 1936, and his violin works played by Monk at a concert that July. By the same process, the BIMS also sent Australian works overseas. In one notable success, music by Benjamin and Agnew was performed in Argentina, facilitated by correspondence between Arlom and Juan Carlos Paz, a founding member of the Grupo renovación – a composers’ association dedicated to the promotion of modernist music in Buenos Aires and the Argentinian sub-section of the ISCM.Footnote 123

In further efforts to promote Australian composers, the BIMS also submitted works to the 1940 (postponed to 1941) ISCM festival in New York. Four works were submitted by Sydney, and four from the BMS branch in Melbourne, which, by this time, also described itself as the Australian section of the ISCM. It remains unclear how the ISCM understood this arrangement, with both Melbourne and Sydney claiming to be the ‘Australian section’ of the organization. The archive of Sydney's financial records (which only cover the years 1931 to 1939) show that the branch sent membership dues to the ISCM between 1932 and 1938, and press reports, meeting minutes, and correspondence between members refer to Sydney as the ‘Australian Section’ inconsistently from 1927.Footnote 124 Programmes and letterheads promote the branch as ‘affiliated’ with the ISCM from 1927, but as the ‘Australian Centre’ only from 1938. For Melbourne's part, the branch's founder and patron, Louise Hanson-Dyer, became the Australian representative to the ISCM in 1928 (for which, Kerry Murphy points out, she would have had to have been elected),Footnote 125 established the Melbourne BMS as the Australian section, and, for a time, paid its membership fees herself. Having left Australia in 1928 to establish her Éditions de l'Oiseau-Lyre press in Paris, Dyer was more internationally mobile than any Sydney committee member and also well-known to many in European ISCM centres. In 1935, however, ISCM secretary Dorothy Wadham wrote to both Melbourne and Sydney asking them to combine forces and share the membership fee between them.Footnote 126 This occurred in 1936, and Dyer acted as delegate on behalf of both branches. For the 1941 festival, Sydney sent a quartet by Burnard, two songs by Horace Keats, and a sonata for violin and cello by Dulcie Holland – none of which were accepted.Footnote 127

The comparative presentation of ‘international’ music in concert programmes, as previously described, was even more strikingly articulated on radio. Public broadcasting had begun in Australia in 1923, and the BMS were early adopters of the medium. From mid-1926, an agreement with 2FC – a major station established in 1923 by the department store Farmer & Co. – allowed the BMS to begin broadcasting some of their live concerts.Footnote 128 In early 1928, however, the rival station 2BL – the first public station in Australia – offered the society a more regular engagement, which they accepted. From March 1928, the society's string quartet played a studio programme once a week.Footnote 129 Additional, more extensive studio programmes were also arranged, and by the mid-1930s these hour-long broadcasts appeared monthly for nine months of the year. From 1935, the first part of each broadcast was devoted to British ‘historical’ music, while the second part featured contemporary works from a different country each month.Footnote 130 Figure 2 shows the July 1936 programme dedicated to late eighteenth-century British and Spanish contemporary music.

Figure 2 An Hour Arranged by the British and International Music Society, 2BL, 3 July 1935. ‘Wednesday July 3 Continued’, Wireless Weekly 25/26 (28 June 1935), 76. State Library of NSW.

This compartmentalized, and almost touristic, approach to illustrating ‘international’ music attempted to quantify the musical characteristics of different nations, and speaks to the same crisis of settler Australian musical identity described earlier. The BIMS's framing of ‘international’ music as intrinsically linked to nation parallels dozens of contemporary articles published in the Australian press on ‘National Music’ or ‘Nationality in Music’, which lay out similarly comparative descriptions of music around the world, in an often essentializing or stereotypical way. Two examples of this style of article appear in the journal Music in Australia in 1929, both written by BMS members. Arthur Benjamin's ‘Contemporary Music’Footnote 131 outlines his thoughts on the musical activities of Europe, sequentially describing the musical characteristics of contemporary music in England, France, Germany, ‘Middle Europe’ (meaning specifically the work of Bartók and Zoltán Kodály), Italy, Scandinavia, America, and Russia. Benjamin is disparaging of the ‘curious form of musical hysteria’ he saw in France – particularly as represented by Les Six – while he characterizes German new music as carrying a ‘feeling that art must be economical’ due to the overwhelming impact of the ‘insensate waste of the war’. Middle Europe presents music ‘with great force and rhythm’ through the employment of ‘native Folksong’, while contemporary composers in Italy were ‘doing splendid work’ in rejecting ‘the stultifying influence of the opera’. Spanish music, he argues, ravishes the listener with ‘fascinating rhythms which are so Oriental in spirit and colour’, while Sibelius represents the ‘lonely figure’ of Scandinavia ‘writing his grey, cold, attractive music. How isolated he is!’ Frank Hutchens's article, ‘Nationality in Music’,Footnote 132 also compares his perception of the characteristics of British, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Norwegian, and American music in turn. Rather than describing contemporary music, Hutchens takes a more historical approach, ranging from Germany – which ‘has remained remarkably uninfluenced by other countries’ in a lineage from Bach to Brahms and Wagner – to Norway and Edvard Grieg, ‘the most national of all composers’ who ‘withstood an over-influence of Wagnerism’.

These types of articles – other examples include the series that Campbell's ‘Nationalism in Australian Music’ appeared in, cited earlier – tend to conclude with a question about Australian music. While these publications demonstrate an evident desire to learn about music from across the world, at the same time, they also clearly form part of an introspective discussion, providing material for comparison and contextualization of activities in Australia. As Hutchens concludes, ‘it is too early to speak’ of Australian music, but points to a combination of historical folk song and landscape as the future basis for a school: ‘if we can so saturate ourselves with the beautiful heritage of English, Scottish and Irish folk songs – a heritage which is ours more truly than we many [sic] realise – and wed that to our innate love of colour and sunshine, we may produce a school of musical composition comparable with anything elsewhere’.Footnote 133

Conclusion

The first years of the 1940s were very bad for the BIMS. Years of economic uncertainty had depleted the society's resources, and Australia's entry into the Second World War signalled further difficulties to come. Subscribers and affiliated schools had been steadily withdrawing support, and attendance at concerts was so low that the society could no longer pay its artists or support the library. The activities of the society were wound up in November 1941 – only temporarily, it was suggested at the time, but they were never to re-open. The branch remained in recess until 1946 when it was decided at a final meeting on 23 May – attended by only eight people – to formally dissolve the branch, citing lack of funding, but also the ‘very greatly stimulated musical concert world’ of post-Second World War Sydney with which they could not compete.Footnote 134 The branch's library was donated to the Musical Association, along with their remaining funds for its upkeep.

Although their existence bordered two particularly difficult periods in Australian and world history – forming out of a post-First World War need for renewal, and closing in the first years of the Second World War – across their roughly twenty years of existence, the British (and International) Music Society played an important role in the cultural life of Sydney. Practically, they provided support and infrastructure for the local musical community, but they also allowed for a philosophical engagement with the world of ‘international’ music, and participated in active nation-building discourses.

Much of the B(I)MS's activity was understood through cultural nationalist frameworks. The ambivalent position of the ‘Australian’, the ‘British’, and the ‘international’ in this context reflects these concepts’ contested nature within interwar Australian cultural identity. While the most obvious aim of the BMS was to promote British music, ‘British music’ had a specific set of meanings in settler-colonial Australia – it could be a patriotic, it could speak to imperial nostalgia, or provide a sense of connection to something larger and more significant that everyday life in Sydney. International music similarly provided a means of reference to a wider world, which was important to understand as Australia negotiated its expanded place within it. Australian music – perhaps the most problematic category for this settler society – meant negotiating the forging of a new identity.

A significant aspect of the society's activities in Sydney was its engagement and championing of contemporary music, which in many instances included explicit examples of modernist works. While the members themselves may not have been particularly concerned with international debates about aesthetic or political agendas associated with the ‘contemporary’, they did still engage with the music. Cultural histories of Australia often suggest that the interwar period was overwhelmingly anti-modernist, following the idea that ‘an improvised, unstated but de facto cultural quarantine existed’, based on the county's preoccupation with ‘the project of cultural nationalism’ while its geographic distance from Europe reinforced ‘tropes of isolation and insularity’.Footnote 135 This may be partly true, but as recent studies have shown, interwar Australia was ‘not isolated and temporally belated’, and, as we have seen, even those proponents of cultural nationalism remained engaged with international culture and modernity.Footnote 136 Certainly preoccupied with the national, Australians also kept an open interest in the world, and hoped to ‘enjoy the fruits of regional leadership’.Footnote 137 At the same time, established imperial networks could themselves function as ‘a vector of modernisation’, allowing Australians access to a range of cultural offerings, rather than simply acting as a dominating force of ‘cultural stagnation’.Footnote 138 The BIMS is a clear example of the way interwar Australians negotiated and challenged the binaries of cultural nationalism and internationalism, as well as modernism and anti-modernism, demonstrating the complex and entangled relationship between these ideas in the Australian consciousness.Footnote 139

Despite the colonial frame of its name, the British Music Society – and later, the British and International Music Society – had international aspirations, which were understood through a framework of Australian cultural nationalism. Initially using the networks of the British Empire to promote modern music and living composers, the Society gradually grew its international network through affiliation with the ISCM, which they used to spread knowledge of contemporary international musics in Australia, and Australian music internationally. A century on from the formation of this society, the BIMS offers an opportunity to reassess Australian music-making in the context of broader international currents, as it responded to aesthetic and political changes and pressures through the interwar period.