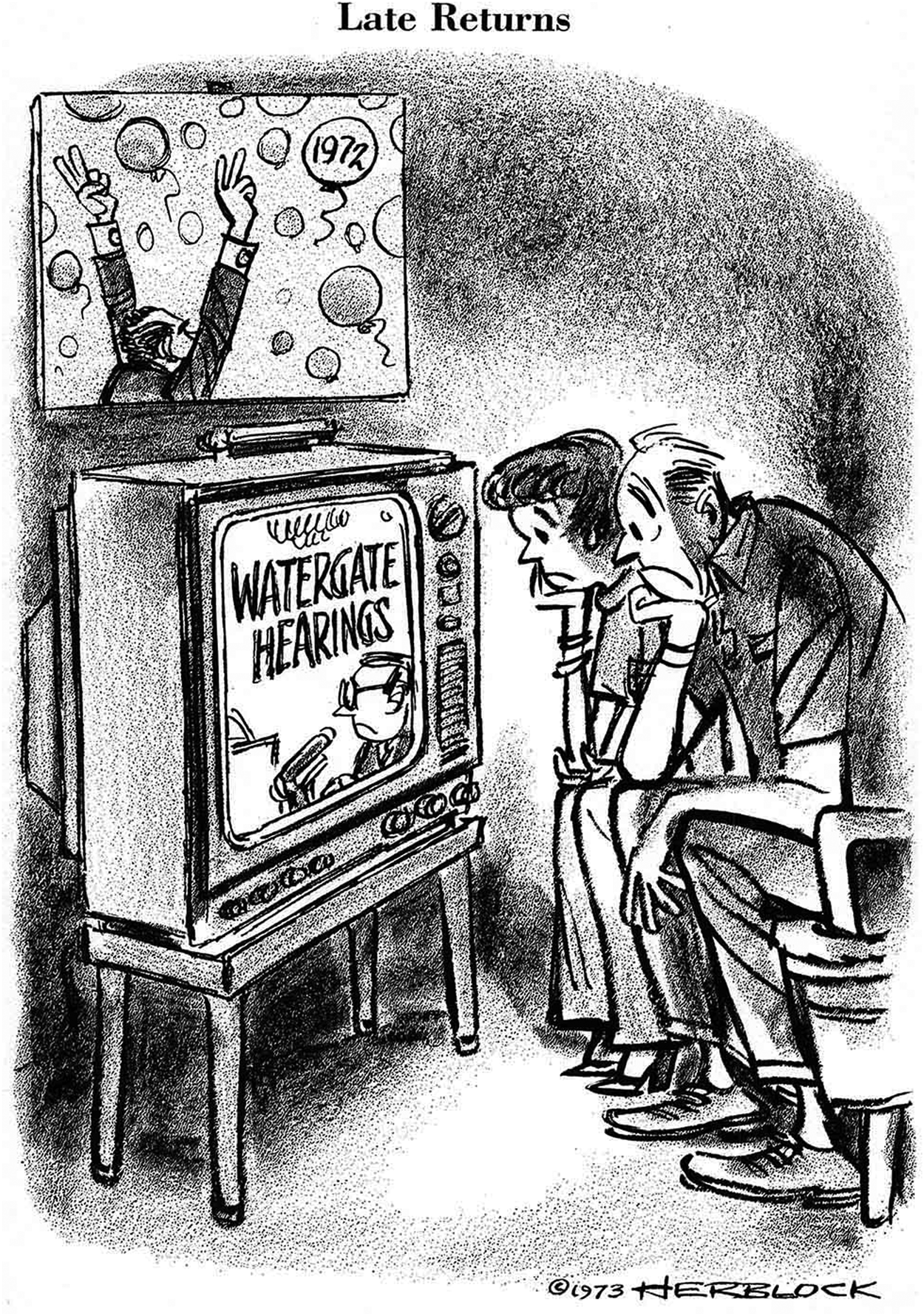

During the summer of 1973, Americans across the country turned their television dials to what the New York Times called the “biggest daytime spectacular in years”: the Watergate Senate hearings.Footnote 1 As a flood of officials from President Richard Nixon's administration testified before the Senate committee, the depth of corruption that permeated the top levels of the White House became clear. The question that Senator Howard Baker (R-TN) posed to Nixon aide John Dean—“What did the president know and when did he know it?”—animated discussions in living rooms and kept viewers glued to their television screens (Figure 1).Footnote 2 As journalist Charles McDowell remembered ten years later, “The people of the United States were caught up in all of this to a degree that might seem unlikely to anyone who didn't experience it. Day after day, week after week, we watched the drama play out in one disclosure after another. It was all on television, and through television the people became a part of the process of judgment.”Footnote 3

Figure 1. 1973 Watergate Hearings, courtesy of the American Archive of Public Broadcasting (WBGH and the Library of Congress). The first day of the hearings is available at https://americanarchive.org/catalog/cpb-aacip_512-6688g8g717

As an experiment in programming, the televised hearings raised a fundamental question: how much television would American viewers watch? Commentary surrounding the hearings emphasized the importance of viewers forming their own decisions in real time. As the public television anchor Jim Lehrer explained on the first day of the hearings, “We think it is important that you get a chance to see the whole thing and make your own judgments. Some nights, we may be in competition with a late, late movie. We are doing this as an experiment, temporarily abandoning our ability to edit, to give you the whole story, however long it may take.”Footnote 4 The characters on television looked different too. Members of Congress, rather than the president, emerged as the stars of the show, inspiring a new generation of younger policy makers to see the connection between investigation, media publicity, and political reform.Footnote 5

Years before C-SPAN and CNN turned public affairs into a 24/7 television event, the Watergate hearings showed how cable television and its controversial and untested business model might work. Rather than simply foreshadowing the cable news environment that would dominate the political landscape two decades later, the televised hearings validated the very idea that cable as an alternative to broadcasting television could and should exist. In an ironic twist, the media event that brought down Richard Nixon and elevated the social prestige of broadcast networks simultaneously helped to transform Nixon's personal war against liberal bias on television into a bipartisan congressional effort to revamp the regulatory landscape that had given broadcasting its authority.

The Senate hearings elevated a national conversation about the role of television in politics that prompted legislators across the political spectrum to reconsider prevailing wisdom about the structure of the broadcast network oligopoly.Footnote 6 Transmitting television signals via the airwaves meant that only a handful of channels entered living rooms through the frequency spectrum. To navigate this technological limitation and acquire higher quality programming, local broadcasters affiliated with a national network. As a result, the three national corporations—Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), National Broadcasting Company (NBC), and American Broadcasting Company (ABC)—controlled most of what Americans saw on television. Conservatives were frustrated by what they saw as the eastern elite and liberal media bias on display in this programming and especially lamented how regulations from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) protected this media consolidation. Nixon speechwriter Patrick Buchanan, for example, contended that Watergate exposed the power of “media monopolies such as CBS, Time-Life. Inc., and the Washington Post Company” to “select, elevate, and promote one set of ideas, issues, and personalities—and to ignore others.”Footnote 7 In Watergate's aftermath, Buchanan and other conservatives expanded their efforts to form alternative media institutions that “exposed” liberal bias while also promoting conservative messages to counter it.Footnote 8

Public television emerged as another solution to viewers dissatisfied with the limitations of the commercial broadcasting structure. While the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 elicited little controversy and passed Congress with ease, debates over the actual funding structure divided law makers.Footnote 9 Liberal supporters believed federal funding would bring to viewers the enlightenment and diversity missing in television's “vast wasteland,” extending the Great Society educational initiatives into the broadcasting realm.Footnote 10 Critics worried that a government-funded network would soon become a vehicle for propaganda and further embed an “East Coast cultural elitism” in the federal bureaucracy.Footnote 11 The Watergate hearings elevated the prestige of the new Corporation for Public Broadcasting. By rebroadcasting the days’ events during primetime evening hours, public television demonstrated its value and made “the whole world realize that we are not the government network,” according to James Karayn, president of the National Public Affairs Center for Television (NPACT), the news arm of public broadcasting.Footnote 12 For the first time, public television offered a news alternative to the commercial networks during primetime hours. Ratings and donations to the network, which had struggled to secure financial footing from the Nixon administration, dramatically escalated.Footnote 13

A third solution appealed to disgruntled television viewers and media activists across the political spectrum: diversification of the dial itself. Given the technological limits of the broadcast spectrum, the demand from policy makers, civil rights activists, feminists, and conservatives for more television access and a variety of perspectives ultimately boosted the fortunes of cable television.Footnote 14 The debate over television that intensified during and after Watergate provoked a series of political negotiations about media's institutional structure—a process that paved the way for economic shifts in the larger communications landscape.

Dominant interpretations of cable television in media history portray the medium as a new technology that exploded in popularity during the 1980s as a result of conservatives’ deregulatory governing strategy. In this view, the Reagan White House led efforts to eschew broadcasting regulations protecting the public interest in favor of policies that promoted the free market.Footnote 15 Journalists, too, have explained dramatic shifts in the media environment as an economic product of the Reagan era: as the cable television industry became larger, it revealed the market success of a “narrowcasting” strategy and “tabloid news shows.”Footnote 16 These works point to the birth of the 24/7 news cycle and the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 as decisive business and legislative changes that launched larger political transformations. But political debates about the place and shape of cable television a decade earlier made these economic and policy shifts possible.

While newer scholarship has revealed the centrality of media in recent American history, political narratives too often gloss over it.Footnote 17 As a result, discussions of cable television portray the medium as inevitably accelerating the role of division and diversion in civic life, ultimately reinforcing ideas of technological determinism that media scholars have long refuted.Footnote 18 Since the 1940s, cable television had proven intensely controversial as both a business and a political idea. Policy makers in Congress and regulators at the Federal Communications Commission actively thwarted its development in favor of an institutional structure that gave broadcasting networks an oligopoly. It took major political and media events, including but not limited to Watergate, to rethink this structure and how cable television could be deployed to challenge television's gatekeepers.

Bridging media and political history reveals that cable television itself did not naturally produce the political polarization and scandal politics that shape the twenty-first century.Footnote 19 It took decades of political mobilization for an industry once dismissed derogatively as filled with “used car salesmen” to become a set of powerful media corporations with loyal consumers who turned to the cable dial for community.Footnote 20 Politicians actively chose to use new mediums to pursue publicity-driven strategies of obstruction as a governing tactic.Footnote 21 And indeed, at the core of this transformation was not a battle between liberalism and conservatism, but a structural shift in the communications industry propelled by a debate over the media as a business, a place for democratic activity, and a central source of power.Footnote 22

For decades, the White House had slowly accrued influence over television's coverage of politics, especially shaping national news programming. The dramatic Watergate hearings reversed this trend. Significantly, they also popularized a conversation about the need for alternative tools for political communication to challenge the growth of a “mediacracy”—what Republican strategist Kevin Phillips had identified as a “quantum shift” in the political economy that made television “the country's number one power center.”Footnote 23 With television as the linchpin of the economy's “new knowledge sector,” Phillips argued that vital questions had emerged about how to deal with “the concentration of media power—and television power especially.”Footnote 24 Comparing network television to “railroads, trusts, and monopolies of the late-nineteenth century,” Phillips predicted that “debate over the status of the media—public versus private control—may become as important an item of the agenda of post-industrial politics as control of capital has been for the industrial era.”Footnote 25 He was right. While historians have spent tremendous time analyzing Phillips's prediction of a partisan realignment that ultimately turned the Sunbelt into a Republican stronghold, his political forecasts also depended on new ideas circulating across the political spectrum about how television could function as a tool to reshape strategies of communication, leadership, governance, and civic engagement.Footnote 26

Harnessing the Power of Publicity

American government has always required political communication. Pamphlets helped spark revolutionary activity, while the printing press expanded the democratic impulse during the early Republic and fostered the fundamental debates of the antebellum period.Footnote 27 Technological developments—the telegraph, telephone, photography, radio, and motion pictures—all brought new opportunities and challenges for political leaders to sell ideas to voters and build national constituencies.Footnote 28 Over the course of the twentieth century, innovative presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin Roosevelt capitalized on new media to elevate the presidency in the public eye. Commanding the spotlight, or what Theodore Roosevelt famously called the bully pulpit, helped to carve out a more prominent role for the president in the legislative process.Footnote 29

The introduction of television in the post-WWII era accelerated this trend by creating a national viewing audience to whom presidents could pitch their personalities on the campaign trail and agendas while in office.Footnote 30 But access to this audience depended on a particular corporate structure for the media that ingrained certain assumptions about news and television's civic responsibilities.Footnote 31 The Federal Communications Commission, an independent regulatory agency created by the 1934 Communications Act, designed and implemented these rules.Footnote 32 Building on policies originally launched with the Radio Act of 1927, radio, and then television, depended on using airwaves classified as “public.” The FCC licensed broadcasters to use a certain spectrum in exchange for serving the public interest and providing some local and educational programs. Soon these local stations formed network alliances to allow for the dissemination of programming created by the three national corporations that ultimately dominated postwar television: CBS, NBC, then later ABC. This regulatory structure produced enormous profits for broadcasters at the national and local level, but it depended on keeping elected officials and FCC regulators happy with programming content.Footnote 33 The key, argued NBC executive Sylvester “Pat” Weaver, was to show that the “interests of the people are serviced by a healthy, advertiser supported television industry, operating efficiently on a national basis.”Footnote 34

Public affairs programs served a particular role in this context. Though news programs frequently cost networks money to produce, they generated political capital that protected the lucrative advertiser-driven entertainment shows from any harmful federal regulations. Local broadcasters knew their representatives well, and made sure to use local television programs to keep them in the eye of constituents.Footnote 35 To fulfill the FCC mandate of “localism” (the requirement that some programs reflect the local interest), broadcasters collected material for their local news programs. Eager to cultivate an image of an active and concerned representative, elected officials happily gave interviews to local television stations to discuss major events. The result? Their perspectives became defined as the news itself and making news became a legislative priority. As one political observer noted in scanning the congressional media landscape in the early 1970s, legislators in the television era quickly assumed that “publicity has an impact on the policy process.” As a result, success became defined “in their own judgment, by the extent and character of publicity.”Footnote 36

These relationships between local broadcasters and congressional representatives created a symbiotic relationship between the legislative branch and broadcast media. Congress built a television production studio to facilitate local news interviews, which ultimately gave incumbents a tremendous advantage over their opponents when it came to reelection.Footnote 37 Some legislators went further and actually bought stock in the local stations in hopes of reaping the financial rewards. When the local broadcasters’ licenses came up for renewal by the FCC, these same elected officials emerged as powerful advocates for these stations on Capitol Hill. If a congressional policy proposal threatened the current broadcasting regime, they squashed it.Footnote 38

At the same time, national network executives cultivated relationships with the president, who frequently appointed FCC regulators with connections to the broadcasting industry.Footnote 39 Dwight Eisenhower, John Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson formed close friendships with these executives and relied on them for advice on how best to utilize the new communications medium.Footnote 40 Johnson's wife also had millions of dollars in Texas television and radio station holdings.Footnote 41 Moreover, when presidents wanted to address a national audience, they had easy access to the networks, which justified airing presidential speeches as a fulfillment of broadcasting's public affairs requirement.Footnote 42 Such speeches afforded presidents tremendous visibility, as they mobilized primetime audiences around their agendas and added more star power to the presidency.Footnote 43 Unlike congressional representatives with only a local reach, presidents drove the national news agenda in living rooms across the country.

But this intimate connection between the presidency and the national networks created tension outside the executive branch. As Senator J. William Fulbright (D-AR) argued in 1970, “television, because of its peculiar capacity and power, threatens to destroy” the “traditional constitutional balance, which we have enjoyed up until the last 25 years.”Footnote 44 While the president enjoyed prominent events like the televised State of the Union address to lay out a policy agenda to the country, Congress, the actual legislative body of government, struggled to challenge the media narrative the president crafted, particularly when it came to television.

Congressional hearings proved an important exception. As one political scientist observed in 1962, the “post-WWII upsurge in congressional investigations primarily reflects an attempt on the part of the legislature to restore a balance of power in the area of publicity.”Footnote 45 As a “form of entertainment,” investigations captured public attention in a way that gave Americans an opportunity to see a complex branch of government at work. As Richard Nixon (R-CA) learned in 1948 during the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings into Alger Hiss, and as Estes Kefauver (D-TN) discovered following his 1950-1951 investigation into organized crime, television provided a path to national recognition that allowed both men to climb the party ladder and secure vice-presidential nominations.Footnote 46 Their contemporaries worried that publicity could overrun democracy, particularly as figures like Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) grabbed power with media-driven spectacles asserting communism's threat. However, McCarthy's widely televised 1954 investigation into alleged communist activities in the Army demonstrated that the spotlight could expose such fearmongering tactics. Not only did Congress vote to censure the Wisconsin senator following these televised hearings in which McCarthy crossed the line by questioning the Americanism of the U.S. Army, but it also began discussing a code of fair practices to shape future hearings on television.Footnote 47

While such high-profile events could momentarily pierce the president's dominance, congressional figures like House Minority Leader Gerald Ford (R-MI) and the antiwar critic Senator Fulbright understood the disadvantages that persisted for Congress as its 535 members battled against one president for inclusion in short segments of news coverage. But they walked a fine line in any efforts to reform this landscape. While they depended on local broadcasters for relevance and reelection in their districts and states, they also understood how the networks skewed the playing field toward the president at the national level. So they worked within the existing system to gain more television access.

The FCC had two requirements that regulated media access: equal time and fairness. The equal time clause mandated that broadcasters provide equal time at the same price for political candidates running for office, and the fairness doctrine required that public affairs programs present an overall balance of oppositional views. However, there existed wide variations in how broadcasters interpreted and applied these principles, and how the FCC enforced these regulations. Moreover, the rules did not cover the question of speeches by elected officials. Networks overwhelmingly considered presidential speeches as news events that fit the demands for programming to uphold the public interest, but frequently ignored the same requests for speeches that came from Capitol Hill. Gerald Ford argued in 1966 that under the Fairness Doctrine the congressional opposition needed to have time to rebut the presidential agenda during national media events like the State of the Union address. The networks complied, but aired Ford's response five days later and late at night. Still it helped to make the campaign for “equal” and “fair” coverage—an idea that animated conservatives for over a decade—central to the Republican Party.Footnote 48

On the other side of the aisle, Senator Fulbright worked with CBS to organize a series of congressional debates about the Vietnam War. In 1966, the network aired “Congress and War.” While the debates did not generate high ratings, CBS President Frank Stanton was proud of the program that informed the broader public about public affairs by giving voice to supporters and critics of the war. He called the January 30 program the “best produced, most useful programs of its kind we had ever done.”Footnote 49 Fulbright capitalized on this goodwill and launched a discussion with network executives about the possibilities of televising the congressional hearings on Vietnam that he was holding. Networks complied and aired the hearings, much to the chagrin of President Johnson. Seeing this televised investigation as a threat to his authority, Johnson first staged an event in Hawaii during which he met with General Westmoreland and the prime minister of South Vietnam in a targeted effort to draw cameras to him, and not the Senate hearings.Footnote 50 He then pressured CBS to stop live coverage of the hearings, and the network, undergoing a corporate restructuring at the time, ultimately decided that the daytime audience of female viewers would not be interested in the debate over Vietnam. NBC continued to air the hearings, and the head of CBS's news department, Fred Friendly, urged CBS to do the same, calling it a “matter of conscience” and “public service in the most basic sense.” But his new boss, Jack Schneider, decided to air reruns of I Love Lucy instead.Footnote 51

Nixon's War against the Media

While Lyndon Johnson attempted to use his clout with the networks to shape their news coverage, his successor did not care to work within the system. Richard Nixon cultivated a very different relationship with the television industry than his predecessors. He felt strongly that national news programs were biased against him, and he deemed the three television networks a part of the liberal establishment that he intended to dismantle. He threatened to revoke broadcast licenses, attempted to censor stories, and bullied reporters with IRS audits.Footnote 52 He also pursued a policy-based solution: to pull back the government regulations that undergirded the system itself—a strategy that would benefit the cable industry that had suffered while broadcasting had flourished.Footnote 53

Categorized during the 1950s and 1960s as merely ancillary to the broadcasting industry, cable television began as a way to extend over-the-air signals to areas with reception difficulty. Entrepreneurs of “Community TV” (or CATV) laid wires that brought these signals into out-of-reach homes. Although Hollywood executives floated ideas around the notion of “pay cable,” in which these operators could offer other types of programming to subscribers, the FCC explicitly limited cable's expansion. Rules prevented the importation of program signals that might detract viewership from local broadcasters. During the 1960s, as demand for television programming increased, the FCC ensured through its regulatory structures that cable would not compete with the commercial broadcasting system in place. For example, in 1966, it ruled that cable operators could not build franchises in the top 100 television markets. The FCC believed the networks’ argument that cable television would splinter audiences with competition and ultimately undermine “free television,” which required large audiences to sell the advertisements that underwrote quality entertainment and civic-minded news programs.Footnote 54 On the FCC view, broadcasters served the public interest, and cable operators threatened it with the possibility that quality programming would migrate to pay television and create an undemocratic cost barrier for the viewing public.

Powerful opposition arose when cable was promoted as a business alternative to broadcasting. In 1964, the former NBC executive Pat Weaver launched a new venture, Subscription TV (STV) in California. He promised to bring viewers more sports, theater, and family entertainment through wired television. Criticism quickly flooded newspapers, the airwaves, and billboards with warnings that if pay TV existed, “stars and programs will desert free TV channels” and limit “free television in the home to the inferior programs.”Footnote 55 Broadcast television, its advocates argued, promoted the public interest by offering top entertainment “in good taste” and balanced public affairs programming “representing all views,” because federal regulations mandated that it do so.

This well-financed organization revealed the lobbying power and public relations savviness of “free TV” advocates—the broadcasters, advertisers, and theater owners who had a financial stake in the status quo. Run by an advertising executive, Don Belding, and Gerri Teasley, a leader in the California Federation of Women's Clubs and an outspoken critic of pay television, the Citizens Committee for Free TV unleashed a political campaign that cost more than a million dollars, bombarding California voters with warnings about the dangers of pay television through direct mail, radio and television broadcasts, newspaper advertisements, billboards, and a flood of brochures.Footnote 56 With compelling messaging that painted pay television as a thieving pirate—one advertisement featured a television with a gun pointed at viewers demanding them to “pay me”—the Citizens Committee first succeeded in getting the initiative to outlaw pay television on the ballot that fall, and then convinced voters to pass it. Even as Pat Weaver signed up eager customers for STV, a majority of voters cast ballots for Proposition 15, which mandated: “The public shall have the right to view any television program on a home television set free of charge regardless of how such program is transmitted.” As a result, subscription television businesses would engage in “unlawful” activities according to the new law.Footnote 57

While the California Supreme Court later ruled the measure unconstitutional, the campaign undermined the new business of subscription television and sent a clear message about what would happen to cable television if it offered alternatives to the dominant broadcasting system. Financially, cable television needed to secure extensive up-front capital to build the infrastructure to wire homes. For businesses to invest in the costly venture of pursuing a new cable franchise (which involved negotiating with municipalities and then the expense of laying the wire), they had to be assured that subscription rates would provide the necessary return on investment. To compete in larger markets with broadcast television, cable operators needed to offer subscribers different types of programming options. The demand for more diversity on the dial existed, and in places like San Diego and New York City, cable franchises grew by skirting FCC regulations and offering distant signals, local programs, and higher quality reception only available on the cable dial. Nevertheless, the regulatory reality and establishment media's lobbying power dramatically curtailed the industry's growth.

Nixon's newly formed Office of Telecommunications Policy (OTP) took on this controversial question of network television power. Its director, Clay Whitehead, and many of its staffers, including future Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and future founder of C-SPAN Brian Lamb, were frustrated by the current state of television and how the three networks limited political discussions and entertainment options. When it came to public television, the OTP argued that government funding should go to local public broadcasting efforts rather than a national public broadcasting network that tilted liberal in the eyes of the president. Its approach dovetailed with the larger ideological argument that Nixon made about a “new federalism” and the need to shift government resources away from a federal bureaucracy to the local level.Footnote 58 But it also coincided with an effort to bully mainstream television into favorable coverage of the Nixon administration, thus stoking fears that the new public television alternative would simply become “The Nixon Network.”Footnote 59 Cable television offered another solution that connected ideas of diversity and competition with Nixon's desire to create outlets he could control while also undermining the political and economic authority of the networks.Footnote 60

Through the OTP, the Nixon administration worked to open up the media landscape with the competition of new technology, notably satellites and cable television. Whitehead had labored intensely during Nixon's first term to ensure that an “Open Skies” policy of competition shaped satellite development, refusing to continue the dominant regulatory model that would have granted broadcasting companies developmental and managerial power over satellites.Footnote 61 During Nixon's second term, the office grappled with how to promote cable television without “reducing the quality and quantity of entertainment programming, programming which is obviously valued very highly by the public.”Footnote 62 In this, OTP officials walked a fine line. They needed to make sure that any efforts to challenge the broadcasting model would not undermine the entertainment programming that the public loved. “Because of the importance of this medium to the public, efforts at reform must be undertaken carefully and with full understanding of the underlying economics of an advertiser supported entertainment system,” Bruce Owen, an economist in the OTP, explained.

A thorough study of the economics of cable television versus broadcasting did not exist, however. Over the previous two decades, feeling threatened by cable as a competitor, broadcasters dominated the public debate about what would happen if cable were deregulated. They swayed voters, representatives, and regulators with their arguments about the need to “keep TV free.” As one Rand report noted in September of 1973, “To date, there is almost no evidence as to whether pay channel services increase penetration rates … and pay channels have not yet been introduced in areas where penetration from broadcast signals would be in the range predicted for urban markets.”Footnote 63 One lawyer in the anti-trust division of the Justice Department was more direct. Broadcasters and their allies had always shaped the contours of the policy conversation surrounding cable television in ways that allowed emotion and “flamboyancy” to dominate the discussion.Footnote 64 Fear always won—fear that Americans would lose their beloved television programs and fear that broadcasters could sabotage re-election campaigns. Hard data, he contended, could change this emotional narrative and encourage a “dispassionate analysis” of the issues at hand. The Watergate hearings provided just that.

The Watergate Hearings: Piercing Holes in Regulatory Logic

On May 17, 1973, viewers around the country turned on their televisions to CBS, NBC, ABC, or public television and saw that the Watergate hearings had begun. With cameras planted in the Senate, viewers watched the drama as it played out. For five days, the networks televised the hearings gavel to gavel. On June 5, the three commercial networks pooled their resources and began rotating coverage; each day's coverage ran a bill of about $100,000 for five hours of testimony.Footnote 65 If viewers missed the day's events, they could tune into public television at night for a replay. Sensitive to the claims by the Nixon administration that news reporting had become no more than “elitist gossip” and aware that commentators would be responding to events as they transpired in Congress, the coverage of these hearings emphasized how viewers could make their own decisions about the proceedings, unswayed by the perspectives of news anchors (whom Spiro Agnew had thoroughly assailed over the previous years for their “provincialism” and “parochialism”).Footnote 66

The hearings provided a natural experiment for theories about viewer behavior that had shaped the television regulatory system, but had never actually been tested, as no alternative to broadcast television programming had ever been allowed to grow. For scholars in newly emergent communications departments across the country eager and equipped to challenge the conventional wisdom about the political economy of the media, the unprecedented length and scope of the hearings provided an opportunity for quantitative analysis of assumptions that had long dominated communications policy.Footnote 67 One such study, “Watergate and Television: An Economic Analysis,” broke ground by arguing that “television viewing can be increased by the addition of new alternatives if they are sufficiently dissimilar to the programs presently being shown.Footnote 68 This study challenged the “passive viewer model” that dominated thinking at the time, with its contention that “people watch television as an activity that fits in with their moods or other activities,” and, therefore, they will simply decide from the available programs what to watch when it is time to watch television. Under this theory, the introduction of more channels (i.e., cable television) would splinter audiences, ultimately lending support to the broadcasting argument that such competition would undermine the advertising model that required high numbers of viewers in order to command the budgets to produce high quality shows.

In this 1976 study, however, economists Stanley Besen and Bridger M. Mitchell (in consultation with Bruce Owen) observed that the Watergate hearings increased the audience size, especially during the day. They concluded that “in contrast to the assertion that total television viewing is insensitive to variations in the available fare, changes in programming alternatives can lead to a marked change in audience size,” rejecting the passive viewer model that had dominated economic assumptions. This study circulated in the Ford administration as economist Paul MacAvoy undertook the controversial task of considering regulatory reform of the telecommunications industry.Footnote 69 He and the Domestic Council Review Group met with economists like Besen, Mitchell, and Owen, who had left the Nixon White House for a faculty position at Stanford in 1974. MacAvoy's White House team concluded that no evidence existed to substantiate the claims from broadcasters that “cable would decimate” its programming. The policy review group recommended that the Ford administration work with the FCC and Congress to pursue legislation to decrease the restrictions currently placed on the “entry and operation of cable television systems.”Footnote 70

The strength of the broadcast lobby ultimately slowed these initiatives, and fears that broadcasters would retaliate during an election year outweighed the arguments for regulatory reform that MacAvoy advanced.Footnote 71 In the end, it would take almost another decade to pass comprehensive and consequential legislation for the cable industry. But the Watergate moment also inspired a new generation of reformers on both the left and the right, all tired of tradition, who also saw the potential of cable to rethink the political and media landscape. As Thomas Whiteside noted in a 1984 New Yorker article on cable television, the “kids of the sixties” refused to “buy all the broadcaster arm-twisting.” As network executives and their lobbying firms elevated the pressure to “kill cable,” young congressional-staff mavericks said, “Let's let this baby loose.”Footnote 72 In 1975, these staffers had new allies who understood media publicity as central to their political agendas. They were the ninety-three men and women who strode into Congress on January 3, 1975 as members of the “Class of ’74,” known popularly as “the Watergate Babies.”

Running for office in 1974 following Nixon's resignation, a slate of liberal Democrats won congressional elections across the country with a message of bringing meaningful reform and transparency to Washington, D.C. Building on the institutional changes launched in the House and the Democratic Party—notably the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 and the McGovern-Fraser Commission that introduced a primary selection process for presidential nominations—these elected officials intended to make national politics more responsive to grassroots activists.Footnote 73 Driven by a desire to end the war in Vietnam, they also pushed the Democratic Party toward issues of racial and gender equality and farther away from its historic connections with segregationist Southerners, many of whom had left the party after Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act during the 1960s. As a product of the “rights revolution,” they framed their policy goals as moral obligations; committed to participatory democracy, these men and women cheerfully dismantled the seniority and secrecy that underwrote congressional activities.Footnote 74

On the right, Watergate inspired a new generation of activists who also entered congressional races during the late 1970s, and they too advocated for “rights” issues that mattered to conservative groups: the right to life and the right to lower taxes, for example.Footnote 75 While at times their platform directly opposed issues advanced by Democratic reformers, the new conservative legislators agreed with their liberal counterparts on the need to deregulate the communications industry.

These legislators were not the first to recognize the bias inherent in network television, but they were the first generation to implement meaningful institutional changes to do something about it. Figures like Gerald Ford and J. William Fulbright had worked within the existing framework of network television, using the FCC mandates about public service, fairness, and equal time to combat the growth of presidential media power. They had wanted to carve out a role for Congress in the media landscape and did not challenge or question how or why three national networks had always dominated the news coverage.

Official doings on Capitol Hill indeed revealed how much the networks still controlled the parameters of legislative debates about the television industry prior to the Watergate moment. Hearings on the First Amendment in March 1972, chaired by Senator Samuel Ervin Jr. (D-NC), brought a stream of network personalities and executives to Washington to discuss the question of government infringement on freedom of speech, and the networks eagerly broadcasted the proceedings. Richard Nixon emerged as the clear villain in the room. Participants thoroughly criticized his administration's efforts to censor the press through formal legal efforts with the Pentagon Papers, as well as with public relations campaigns launched by Vice President Spiro Agnew, who seized every possible chance to highlight the elitism and bias in the press.Footnote 76 Walter Cronkite delivered a crisp and authoritative statement to the committee and the cameras, just as he did each night, to defend the civic role of television news. It was a “masterly” performance, noted Laurence Leamer in Harper's Magazine. However, when addressing the issue of diversity in television, notably what the broadcast networks were doing to promote it, Cronkite sidestepped the question and occupied that “well-traveled border between deviousness and truth where public-relations men make their living.”Footnote 77 Cronkite applauded the future of cable and the importance of “wired cities of tomorrow,” but neglected to mention the simultaneous fight by network television to “cripple” the industry. And yet, Ervin and other committee members never questioned his assertions, and the hearings, designed to defend the network against the Nixon administration, became “solely a platform for the networks’ point of view.”

The final witness, George Washington University law professor Jerome Barron, concluded the hearings by calling out the contradiction embedded within the entire process. “I think that it is one of the great public relations triumphs of the twentieth century over the eighteenth that the broadcasters have managed to identify themselves so completely with the First Amendment.” Sure, he said, freedom of speech is safe for the executives and anchors that appeared during the hearings. “But they are just three or four out of 200 million … it is a combination of the marriage of technology and pressure of the concentration of the economic system which has given them this enormous power.” Furthermore, he argued that “it is nothing short of amazing to me for a representative of broadcasting to contend that now they should be free from all regulations and yet they don't suggest everybody should be licensed anew as an original proposition. To that extent they are not willing to abdicate or abandon government aid.” But this strident critique of the logic that undergirded the network system went unheard. The cameras that had captured Cronkite's testimony packed up, and no one televised Barron's testimony. With no cameras, senators left the hearings, and so too did the audience. Leamer pointed out the irony: in hearings on free speech, “Professor Barron and his ideas had been denied their freedom of speech.”

Despite the growing concern about television that pervaded Congress during the early 1970s, its members did not fundamentally challenge the structure of the media institution that had transformed American politics in these increasingly undemocratic ways. The conversations centered on censorship and the First Amendment. Nixon and conservatives argued that the monopolistic power of television networks threatened their freedom of speech, while television reporters and journalists defended their work and contended that Nixon's war on the media created a “fear in the air” that undermined the ability of a democratic press to function freely.Footnote 78

A new generation of scholars in emergent media studies departments, along with economists taking a fresh look at regulatory policies, exposed the fundamental issue: Congress did not want to change the system that afforded its members so much power. With deep connections in local media markets and a production studio at their fingertips, senators and representatives had tremendous assets on hand for their reelection. Most local news programs accepted pre-recorded interviews as the news, allowing Congress and the press to become “partners in propaganda,” as one critical observer put it.Footnote 79 Congressional leaders complained about how the president had become the star of the network news programs, not the underlining structure or values of the news productions themselves. The televised Watergate hearings, however, changed the conversation about the importance of publicity and political performance, highlighting the need for transparency and access that only a different form of television could provide.

Civic Engagement through the Tube

The Watergate hearings raised a fundamental question: How should the country grapple with political scandal and abuses of power: through the court of justice or the court of public opinion? President Nixon and his defenders argued that the decision to televise the Senate hearings constituted proof of the “political witch hunt” that the liberal media had pursued against him all his life.Footnote 80 Vice President Agnew criticized the “Perry Masonish impact” of the media event that “will paint both heroes and villains in lurid and indelible colors before the public's very eyes.” He lamented that the hearings were “essentially what is known in politics as a ‘beauty contest’ and the attractiveness and presence of the participants may be more important than the content of the testimony.”Footnote 81 Even worse, Agnew contended, was how the camera encouraged “an emotional and dramatic factor which gets in the way of a deliberate, dispassionate pursuit of truth.” He felt that a public process, which also allowed the flourishing of faulty information and emotion, would harm the justice system.

Senate Majority leader Mike Mansfield disagreed. He saw television coverage—gavel to gavel “unencumbered by reportorial filters of interpretation”—as giving the public a stake in the process and bolstering its integrity.Footnote 82 Television anchors also emphasized the importance of viewer activism and decision making as to guilt or innocence. As the hearings continued for hours a day over the course of the summer, and then on public television into the evening hours, the public welcomed a shift in coverage that went beyond the thirty or sixty minutes traditionally allocated for news programming (Figure 2). Thousands of citizens wrote letters to their local public television stations thanking them for broadcasting the hearings and explaining the transformative role that this comprehensive portrayal of the political process played in their lives. One viewer complained of a “Watergate hangover” from staying up too late watching the re-runs of the day's proceedings, while another complained that watching such extensive coverage at night “was ruining my sex life.” According to another, while the hearings had “upset my life considerably” by commanding such attention, it had overwhelmingly resulted in more civic engagement and signaled a deep personal desire to understand “how my government worked.”Footnote 83 The hearings validated the ideas that OTP staffers like Bruce Owen and Brian Lamb had about how news could work when the people themselves could decide what happened, rather than relying on elite newscasters to interpret current affairs.Footnote 84

Figure 2. A 1973 Herblock cartoon, © The Herb Block Foundation. Used by permission of the Herb Block Foundation.

During Watergate, the perils of publicity faced off against the merits of transparency. Nixon supporters argued that Democrats had now assumed the publicity-seeking and reputation-damaging role that Joseph McCarthy once occupied (ignoring, of course, the role Nixon had previously played on the House Un-American Activities Committee). The Washington Post, however, emphasized that the charges of bribery and obstruction demanded a public conversation with journalists, Congress, and voters all playing a role. How much of the critique of “trial by publicity” actually “proceeds from an excessive effort to shield the President from the due process of a political system which also explicitly provides for a free press, for free expression and for the vigorous discharge by Congress of its constitutional responsibilities?” the Post asked.Footnote 85

After a decade in which trust of elected officials had dissipated and campaigns for transparency rooted in the public's “right to know” increased, the citizens joined the political process through television.Footnote 86 Viewers wrote letters to local newspapers asking that the hearings “keep showing citizens the decay which must be cleaned out.”Footnote 87 The senate committee quickly catapulted in status, as figures such as Sam Ervin became national celebrities. Staffers received calls with job requests, marriage proposals, and offers for lucrative speaking engagements. Letters poured in with advice on what to wear on television and packages even arrived with tasty cigars. But a consensus emerged amid the fanfare: viewers constantly celebrated “how happy they are to see America has ‘honest,’ ‘sexy,’ ‘adorable’—politicians working for them.”Footnote 88

While the Senate received the majority of the attention from the Watergate investigation, the House also received an injection of favorable publicity as the House Judiciary Committee deliberated the case for impeachment the following year. Immediately, journalists posed the question: will these committee meetings also be televised? The networks agreed to rotate coverage as they had the previous summer, and public broadcasting planned to present evening coverage by videotape. Such programming, however, required a vote to change House procedure to allow cameras in meetings traditionally closed to the public.Footnote 89 A range of voices, mostly on the Democratic side, emerged to make the case for televised proceedings to encourage “public confidence.” While the committee decided to keep its deliberations on the evidence itself closed, “in accordance with a House rule providing for private consideration of any evidence or testimony that might ‘tend to degrade or defame’ individuals,” it did vote to televise the final committee vote.Footnote 90 According to the New York Times, the concern about spectacle and grandstanding on television was outweighed by a deep desire to convey the severity of the charges and uphold the integrity of the process. Television proved a powerful conduit to connect the people to representatives, ultimately allowing those who cast a vote to bring an impeachment trial to the Senate an opportunity to “explain themselves” to their constituents that far exceeded what they could do in a “whole year of speeches, newsletters, and news conferences.” The stakes were high, perhaps just as “profound as [television's] impact on presidential politics since 1960.” The result? “Through a means the Founding Fathers never dreamed of, the Representative could truly become the Federal office-holder closest to the people.”Footnote 91

As communications professor at American University Robert O. Blanchard presciently predicted in his extensive 1974 study, Congress and the News Media, “After many years of preeminent executive power and news media attention, Watergate may have sparked a new period of congressional dominance in national decision-making—with the assistance of the news media.”Footnote 92 Even before the Watergate saga came to an end, Congress began studying how to embed television more thoroughly within its operations. In February 1974, a Joint Committee began hearings on the topic and the following year issued a report that recommended moving forward with trial experiments to broadcast future House and Senate floor proceedings to the public to “bring meaningful information more directly to more of our citizens.” According to Senator Lee Metcalf (D-MT), who chaired the committee, Congress needed to interrogate any “customs or other aspect of our operation that might discourage the news media or the public generally from seeing—and understanding—the activities and role of the National Legislature.”Footnote 93

The ninety-three new members who had just joined the House of Representatives overwhelmingly agreed. Having grown up with television, these younger representatives brought with them an innate sense of the importance of the media. They also demanded transparency, which resulted in a range of “sunshine laws” across all levels of government. As conservative commentator Irving Kristol wrote, however, “this sounds good” in theory, but the implications were more problematic because requirements penalize “candor and compromise and reward aggressive ‘grandstanding.’”Footnote 94 The newly elected Representative George Miller (D-CA) remembered the consequences in more strident terms: “We were a conquering army. We came here to take the Bastille. We destroyed the institution by turning the lights on.”Footnote 95

In the context of 1975, the push to eliminate secretive voting, break down the seniority system in Congress, and introduce more accountability made sense. Legislators challenged procedures that had long undermined progressive policy initiatives—from civil rights to more recent concerns about Vietnam and the environment. They also questioned regulatory relationships, wondering how government agencies had become captured by the industries they were supposed to oversee.Footnote 96 In terms of policy and publicity objectives, Congress simultaneously took a hard look at how television functioned as an institution, and began to question the logic of the corporate broadcasting monopoly. Television coverage gave Congress a taste of the limelight during the Watergate hearings, and its new members were unwilling to retreat to the background after Nixon left office. Significantly, post-Watergate representatives—from Democrats like Timothy Wirth of Colorado and Al Gore of Tennessee, to Republicans like Newt Gingrich of Georgia and Bob Walker of Pennsylvania—actively looked for ways to craft new media strategies that could bring them to prominence and put Capitol Hill at center stage. They found a solution in cable television.

Taking Cable Seriously

By the 1970s, cable operators had also become more politically savvy, following in the footsteps of the broadcasting industry in their quest for political recognition and economic opportunity. As early as 1969, cable businessman Bill Daniels urged cable operators to take advantage of the “public relations opportunity” that elections offered to provide low cost or “preferable free time” to political candidates on cable television. Understanding that broadcasters had long used their ability to run political ads at reduced rates to “curry political favor,” Daniels recommended a “full-fledged effort by the Industry to gain the attention of Congress through a voluntary, but industry-wide program in the public interest of making time available at little or no cost in relatively large quantities.”Footnote 97 Over the course of the 1970s, the industry's lobbying arm, the National Cable Television Association (NCTA), produced local and national publications that explained to politicians the merits of cable television and offered strategies on how to integrate cable, rather than broadcasting, into campaigns and Congressional operations.Footnote 98

In 1977, then, former OTP staffer Brian Lamb had an idea to capitalize on the discussions brewing in Congress about how to televise its proceedings with a project that would elevate the prestige of the cable industry, and ward off criticism that it put greed over the public interest.Footnote 99 “The way that CBS, NBC, and ABC became powerful was through the news,” Lamb later recalled, so he urged cable operators to get involved in the news industry to be “taken seriously in Washington.”Footnote 100 He worked diligently to convince cable companies to pledge financial support to cover the cost of a public affairs cable channel that would bring government directly to cable viewers. He also persuaded industry allies like Rep. Lionel Van Deerlin (D-CA), whose home district had one of the largest cable franchises in the country, that cable could provide the House the access, technology, and, most importantly, control over cameras that broadcasting could not or would not. Delivering the gavel-to-gavel floor proceedings of the House of Representatives, Cable Satellite Public Affairs Network (C-SPAN) offered congressional representatives opportunities to bring their floor debates and activities to constituents.Footnote 101 NCTA lobbyist Thomas Wheeler indeed perceived how the network would legitimize the industry and help with the regulatory debates it continued to lose in Congress.Footnote 102 C-SPAN's first investor, Bob Rosencrans, agreed with Wheeler: “I was tired of knocking on congressmen's doors to explain what cable television was.… So if nothing else, I thought it would put cable on the map in Washington.”Footnote 103

The launch of C-SPAN in 1979, and to a lesser extent the Cable News Network (CNN) in 1980, created programming that injected cable television directly into national politics. C-SPAN took this mission seriously, as its funding came from the cable industry and its existence depended on proving its political value to cable operators. It actively cultivated its own relationships with viewers and developed innovative call-in programs that allowed guests—generally media figures and national politicians—to discuss the news of the day with cable subscribers. It even crafted an educational program to promote civic engagement among high school students in partnership with the Reagan administration, which allowed students to interview the president on C-SPAN's “Close-Up” program.Footnote 104 The President watched C-SPAN regularly, referencing it when discussing legislative debates and even calling in as a viewer. One Washington Post journalist reported that the network managers had both “pride and chagrin” when one day the “president couldn't get through because too many other callers were lined up ahead of him.”Footnote 105 As the C-SPAN's “most famous viewer,” Reagan also would call guests from the call-in show to discuss their comments, even once telephoning a journalist for misrepresenting one of his press conferences.Footnote 106

While C-SPAN remained a nonprofit organization and celebrated its public service contributions, CNN was a business venture focused on the bottom line. Ted Turner, an eccentric millionaire sailor, got his start in television by establishing an Atlantic “SuperStation” in 1977 that used satellite to relay programming across the entire country.Footnote 107 He hated the commercial television networks, which he viewed as biased, elitist, and monopolistic. While Turner famously dismissed news in favor of entertainment on his Atlanta station, at a cable television convention, he discussed with Reese Schonfeld, who ran a service providing news to independent broadcasters, the idea of a twenty-four-hour news station as a business entity that would make money both through advertisements and subscriptions. By naming it Cable News Network, Turner went all in on the cable industry and later emphasized how news programming that promoted the cable industry helped him get carriage from cable operators and allowed him to make money on the expensive operation (something he finally did by 1985).Footnote 108

Both C-SPAN and CNN hinged on the idea that there was a hunger for 24/7 public affairs, and that if politicians benefited personally from the medium, they would extend its reach. Both concepts advanced the bottom line of the cable industry by promoting new programming to potential subscribers, and by convincing policy makers of the need to advance, rather than impede, cable television's reach. As the first representative to appear on C-SPAN, Al Gore delivered a hopeful speech about how cable television could expose political misconduct and implant the lessons of the televised Watergate hearings within the legislative branch. “Television will change this institution just as it has changed the executive branch,” predicted Gore. He anticipated that the “good will outweigh the bad” because the “solution for the lack of confidence in government … is more open government at all levels.”Footnote 109 Ted Turner made similar claims the following year when he launched CNN with the goal of creating a “positive force where cynics abound,” providing “information to people when it wasn't available before” and offering “those who want it a choice.”Footnote 110 He contended that the American people who “thirst for understanding and a better life” would now find it on the cable dial.

With C-SPAN, in particular, congressional political incentives combined with the industry's business strategies to incorporate cable television into civic initiatives and the operations of government institutions. When C-SPAN launched in 1979, representatives celebrated it as an opportunity to “boost their political stock” at home.Footnote 111 Both Democrats and Republicans in the House hoped to build a national audience for their respective agendas. Whereas Speaker Tip O'Neill had famously asserted that “all politics is local,” in the C-SPAN era, all politics became nationally televised. O'Neill claimed that C-SPAN helped the Democrats electorally in the 1982 midterm elections, and William Alexander, a Democrat from Arkansas, pioneered the idea of using Special Order speeches (which occurred at the end of business for the House) and one-minute speeches to boost representatives’ profiles on the local news in an effort to “learn how to use television to compete with Reagan.”Footnote 112

In addition, a “crew of junior Republicans—the regulars include [Bob] Walker, Newt Gingrich (Ga.), Connie Mack II (Fla.), Vin Weber (Minn.), and Daniel E. Lungreen (Calif.)” captured national attention for their innovative use of the cameras in the service of partisan goals. “While largely unknown in official Washington,” observed the Washington Post, this crew “is developing a national following.”Footnote 113 Pursuing what newspapers called “parliamentary guerrilla warfare,” these conservative representatives used procedural challenges to Democrats’ agenda to force debate over conservative issues of school prayer and a balanced budget. At the time, C-SPAN reached over 16 million homes, and while the network did not track audience numbers or ratings, Gingrich estimated that 200,000 people could be watching at any moment, which he called, “not a bad crowd” for a “nation-wide town hall meeting.”Footnote 114 His team of “self-styled Republican guerrillas” also took advantage of Special Orders at the end of the day to give strident, fiery speeches to cable viewers during primetime, and without anyone in the chamber to challenge them (a situation the camera did not reveal because it focused only on the speaker). Such tactics attracted new viewers who called congressional debates “the most fascinating thing that's ever been on TV,” and they earned Congress the title of “Best Little Soap Opera on Cable” from the Washington Post in 1984.Footnote 115

That spring, however, just as C-SPAN celebrated its five-year anniversary, a battle erupted over acceptable political behavior in what soon became known as “CamScam.” Fed up with the hostile and aggressive speeches that these junior Republicans had delivered during the Special Orders at the end of the day to an empty chamber, Speaker O'Neill ordered the cameras to pan the room, showing viewers the empty seats and explaining why Democrats did not respond to allegations against them. Per the agreement with C-SPAN, the House controlled the cameras, and O'Neill had previously emphasized the importance of keeping the camera focused on House speakers, not the chamber, to avoid catching any embarrassing behaviors on camera and to prevent misconceptions about the nature of legislative work, which is frequently done outside the House chamber. In response, Gingrich and his team of “guerilla warriors” continued to assail the Democratic leadership, highlighting its hypocrisy in changing the camera angles (Figure 3). O'Neill eventually fired back, calling Gingrich's House conduct the “lowest in my 32 years here,” only to be ruled out of order for personally attacking Gingrich.Footnote 116

Figure 3. Political cartoon by Mike Morgan published in the Macon Telegraph & News, May 23, 1984, folder 54, box 4, C-SPAN Archives. Courtesy of Mike Morgan.

C-SPAN emerged as the real winner in the televised battle. Brian Lamb called the incident a “terrific boost for the whole concept,” because it got people talking across the country about Congress and cable television.Footnote 117 He was right. Editorials from Oregon to Texas, and from Iowa to Maine weighed in on the debate. Some criticized “tricky Tom O'Neill” for trying to be “Cecil B. DeMille,” while others called attention to the deceptive tactics of Republicans, reminding them that “those who live by the tube die by the tube.”Footnote 118 The majority of the editorials, however, dismissed both sides as “plain silly,” “sophomoric,” and “foolish,” focusing instead on the specifics of how C-SPAN actually worked (including the fact that it was funded by cable companies themselves) and the growing power of television in politics.Footnote 119

Moreover, the publicity surrounding CamScam showed that people watched and valued the public affairs channel. According to one newspaper in Boulder, Colorado, “When this service started five years ago, cynics figured that the only viewers would be desperate people stuck at home who had seen all the reruns on other channels. But what's this? Thousands, maybe millions of voters are watching, and sending letters to their representatives about what they have seen.”Footnote 120 The editorial page at the Dallas Morning News agreed: “Anything—anything—that goes on television on a national scale at whatever hour, on whatever subject, draws audiences of a size that most politicians would kill for. New fact of life: The politician who speaks to the camera whether he is in an empty House or atop Mount Everest at midnight, speaks to the multitudes.”Footnote 121 Even after the CamScam controversy, Speaker O'Neill held firm that television coverage of the House exceeded his “wildest hopes” by reclaiming the national importance of the House and its members.Footnote 122

With C-SPAN and CNN, cable television transformed political entertainment and special events like congressional investigations into everyday television. As Brian Lamb explained in 1984, the cable industry's fight for deregulation, which centered on “the premise that it could provide many new types of programming at a low cost,” intersected with developments in Congress and the House's decision to “seriously address television.”Footnote 123 Driven by a desire to throw off the regulatory measures that had long hampered its growth, the cable industry took advantage of this post-Watergate political reckoning with television and blazed a new path for public affairs programming that eschewed the economic limitations and political assumptions that had long shaped network news on broadcast television. In fact, one viewer called C-SPAN “one of the best things to happen to TV since the Watergate hearings,” an observation that the cable network happily shared with Speaker O'Neill.Footnote 124

While Newt Gingrich and Tip O'Neill engaged in televised partisan bickering about camera angles, Congress displayed bipartisan support for the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984. Introduced by a Republican senator from Arizona, Barry Goldwater, and a Democratic representative from Colorado, Timothy Wirth, the bill passed by a vote of 87–9 in the Senate and a voice vote in the House. Wirth called the bill “the cable television industry's dream” because it allowed the industry to “get out from under this vast regulatory structure that had been built by the FCC with the networks in collusion.”Footnote 125 The act transformed the cable industry into a corporate power player by erasing FCC regulations on programming and local franchise agreements that specified high service charges and other requirements for operation.Footnote 126

Grandstanding, spectacle, transparency, and public access to information—the values celebrated and feared eleven years earlier during the Watergate hearings—all came together on the cable dial. As one viewer explained,

I watch C-SPAN because it takes me beyond the tidied Congressional Record, past the deletions of the daily press, beyond the strangely attractive reporting of the network news, straight to the House and Senate floors, even into the subcommittees, where our elected representatives stand directly before us in all their eloquence and inarticulateness, their wisdom and foolishness, their openness and evasiveness, their glory and disarray.… C-SPAN opens the discussion to an entire nation and draws the eyes and ears of a people to the deliberations at hand.Footnote 127

Cable television did not simply foment the polarization that “balkanized the public sphere.”Footnote 128 It transformed the public sphere into an entity profoundly shaped by genuine debates over media access, performance, and privatization. It turned the revolutionary idea of the televised Watergate hearings—that the people should be “part of the process of judgment”—into a reality, but only for those who could afford the subscription fees. As cable shifted more control to the television viewer, it also shifted more power to the business of television, simultaneously transforming and strengthening the power of the “mediacracy” in American political life.