Hallucinations commonly are associated with psychiatric or medical illness (Reference Slade and BentallSlade & Bentall, 1988; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). However, they can occur also in ‘normal’ individuals, and more people experience hallucinations than come into contact with psychiatric services (Reference Romme, Honig and NoorthoornRomme et al, 1992). Surveys of college students have found that a substantial number have experienced hallucinations at some time in their lives (Reference Posey and LoschPosey & Losch, 1983; Reference Young, Bentall and SladeYoung et al, 1986; Reference Barrett and EtheridgeBarrett & Etheridge, 1992). Population-based studies have attempted to estimate the prevalence of hallucinatory experiences in adults and have found the lifetime prevalence to be 8-15%, depending on age and gender (Reference Sidgewick, Johnson and MyersSidgewick et al, 1894; Reference TienTien, 1991). Reports of cultural and ethnic variation in the experience of hallucinations (Reference Al-IssaAl-Issa, 1977; Reference SchwabSchwab, 1977) also suggest that hallucinations are not necessarily pathological phenomena.

This study analysed data collected from a national community survey in order to examine the prevalence of hallucinatory experiences in the general population of England and Wales. The analyses addressed three questions: what is the occurrence of hallucinations in this national community sample; do the rates vary across ethnic groups; and to what extent are the reported hallucinations associated with mental health problems?

METHOD

The data were obtained from the Fourth National Survey of Ethnic Minorities, conducted between 1993 and 1994 by the Policy Studies Institute and Social and Community Planning Research. The survey explored the experiences of ethnic minority people living in England and Wales, and covered mental health, physical health and a range of socio-economic and demographic variables. The study was funded by the Department of Health for England. Data were collected from representative community samples: 5196 members of ethnic minority groups, comprising Caribbean, Indian, African Asian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Chinese respondents; and a sample of 2867 White respondents. The age of the respondents was more than 16 years. The ethnic minority sample was recruited in areas identified from the 1991 Census on the locations of the ethnic minority population of England and Wales (Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, 1991). The sample frame included areas of low and high ethnic minority density. Actual respondents were identified through a modified household sampling process known as ‘focused enumeration’. The White sample was identified using a more straightforward stratified design. Details of the survey methods can be found in Nazroo (Reference Nazroo1997) and Smith & Prior (Reference Smith and Prior1997).

The initial screening stage of the mental health assessment used parts of the revised version of the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS—R; Reference Lewis, Pelosi and ArayaLewis et al, 1992) and the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ; Reference Bebbington and NayaniBebbington & Nayani, 1995). Questionnaires were administered by interviewers matched for ethnicity and language. The CIS—R was used to identify those who possibly had a neurotic disorder, particularly depression, and the PSQ was used to identify those who possibly had a psychotic disorder. The PSQ has questions on hypomania, thought insertion, paranoia, strange experiences and hallucinations. The two hallucination questions are:

-

(a) ‘Over the past year, have there been times when you heard or saw things that other people couldn't?’

If yes,

-

(b) ‘Did you at any time hear voices saying quite a few words or sentences when there was no one around that might account for it?’

Respondents were asked all the questions from the PSQ; the usual system of a cut-off after a section was answered positively was ignored. The survey also asked half of the sample about their use of medication and history of illness. Those respondents who scored positively for symptoms on either the CIS—R or PSQ were invited for a follow-up interview and underwent a more detailed psychiatric assessment using version 9 of the Present State Examination (PSE; Reference Wing, Cooper and SartoriusWing et al, 1974). The interview was undertaken by ethnically and language-matched psychiatric nurses or doctors.

For the current analysis, we examined the frequencies of responses to the two questions asking about hallucinations on the PSQ. We also examined the PSE classification for those respondents who endorsed both PSQ hallucination questions and were followed up. Chi-squared tests were used to investigate possible bivariate relationships between reports of hallucinations and other variables. In the ethnic minority sample, the data from the four South Asian groups were combined (to maximise sample sizes and because there were minimal differences between the individual groups) and the data from the Chinese group were not used (because the sample was too small for independent analysis).

RESULTS

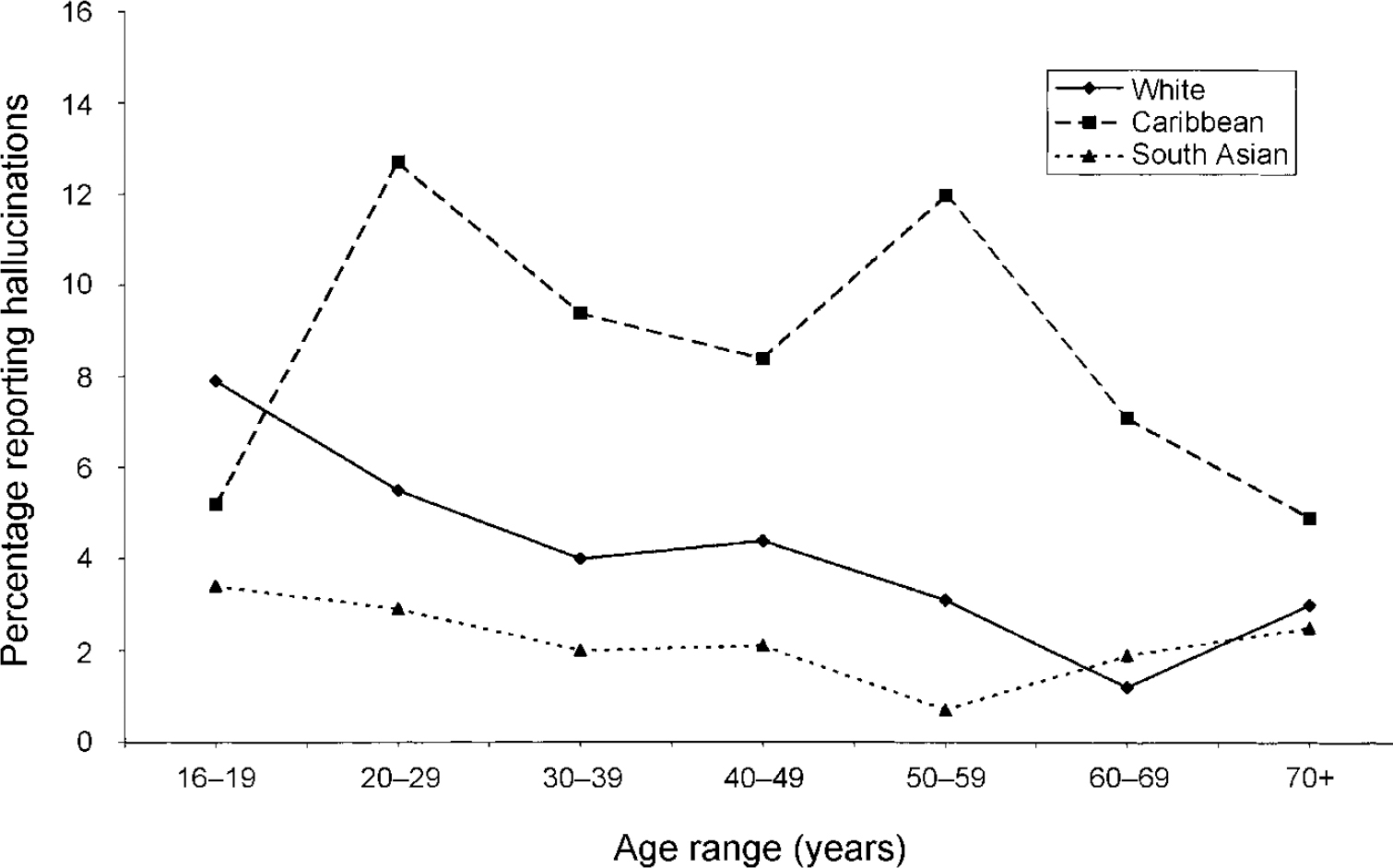

Table 1 shows responses to the PSQ questions. In the White sample, 4.0% responded positively to the first hallucination question and 1.2% endorsed both hallucination questions. We also examined endorsement of the hallucination questions in relation to the other PSQ items: 1.8% endorsed a hallucination question plus another question on the PSQ, whereas 2.3% endorsed the hallucination items only. The results from the White sample provide an estimate for the general population (because of the low percentage of ethnic minorities in the UK). Figure 1 shows the age distribution of hallucinations. In the White sample, hallucinatory experiences were most common in the 16— to 19-year-olds. There was no significant difference between males and females in the prevalence of hallucinations (4.9% for males, 3.3% for females).

Fig. I Age occurrence of hallucinations.

Table 1 Percentage of respondents who endorsed the hallucination questions on the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ)

| Ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Caribbean | South Asian | |

| Yes to first hallucination question | 4.0 | 9.8 | 2.3 |

| Yes to both hallucination questions | 1.2 | 2.8 | 0.6 |

| Yes to a hallucination question plus another PSQ question | 1.8 | 4.2 | 1.1 |

| Yes to a hallucination question but no other PSQ question | 2.3 | 5.7 | 1.2 |

| Number of respondents (weighted count) | 2867 | 1567 | 3238 |

| Number of respondents (unweighted count) | 2867 | 1205 | 3777 |

The prevalence of hallucinatory experiences varied across the ethnic groups (Table 1). Compared with the White sample, the rates were 2.5-fold higher in the Caribbean sample and approximately half as common in the South Asian sample. In the Caribbean sample, the prevalence of hallucinatory experiences was greater in the 20-29 and 50-59 years age groups (Fig. 1). The age distribution of hallucinations in the South Asian sample was fairly constant. Females reported more hallucinatory experiences than males in the Caribbean sample (11.8% ν. 7.4%, χ2=7.5,P=0.006) but there was no gender difference in the South Asian sample (males: 2.5%, females: 2.1%).

To examine whether rates of hallucinations in the ethnic minority samples varied by migration, the samples were divided into migrant and non-migrant groups. Those who were born in Britain or who moved before the age of 11 years were classified as non-migrants and those who migrated at age 11 years or older were classified as migrants. In the Caribbean group there was no difference in the occurrence of hallucinations according to age on migration to Britain (9.3% ν. 9.4%). However, in the South Asian group non-migrants reported significantly higher rates of hallucinations than did migrants (3.7% ν . 1.2%, χ2=25, P<0.001).

Our third research question concerned the mental health status of those respondents who endorsed the hallucination questions on the PSQ. From the questions on medication use and diagnosed illnesses, those who had taken antipsychotic medication or had a diagnosed psychotic disorder could be identified. Only a very small percentage of those people who reported a hallucinatory experience on the PSQ had a psychotic illness according to these criteria (Table 2). This percentage was lowest in the Caribbean sample (χ2=10.2,P=0.006).

Table 2 Occurrence of psychosis in respondents with hallucinatory experiences

| Ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Caribbean | South Asian | |

| Yes to any hallucination question | 4.0 | 9.8 | 2.3 |

| Reported diagnosis or treatment for a psychotic illness | |||

| Percentage of those reporting hallucinations | 11.4 | 1.9 | 6.7 |

| Percentage of total | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

Of the 89 respondents who endorsed both hallucination questions on the PSQ, 52 were followed up and interviewed using the PSE (26 White, 15 Caribbean and 11 South Asian people). Nine (17%) of these had one or more hallucination symptom on the PSE and five (10%) met the criteria for a hallucination syndrome. In terms of diagnostic class, 13 people (25%) had a psychotic disorder, 29 (56%) had an affective disorder and 10 (19%) did not meet any diagnostic criteria. The percentages with any diagnostic class were similar in the White and Caribbean groups but lower for the South Asian group.

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of hallucinations in the sample

The prevalence of hallucinations in this sample is low. The results from the White sample provide an estimate for the general population in England and Wales: 4% of people reported hearing or seeing things that other people could not. Unfortunately, these data do not provide details of the precise nature or context of the hallucinatory experiences reported and may overestimate the prevalence of ‘true’ hallucinations. For example, hallucinations occurring in states of altered awareness also could have elicited positive responses on the PSQ. In addition, we were unable to examine whether these hallucinatory experiences were drug related, because the survey did not ask about illicit drug use.

The estimated figure is considerably lower than the rates of hallucinations reported by other epidemiological studies. For example, data from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program in the USA showed that the lifetime prevalence of hallucinations in this sample of 18 572 community residents was 10% for men and 15% for women (Reference TienTien, 1991). What might account for the low prevalence rate in this study? The figure reported here represents annual prevalence, whereas previous studies have reported lifetime prevalence. The lifetime prevalence of hallucinations in this sample would be higher than 4%, but possibly not the three to four times higher that would be needed to bring it into line with other studies. Prevalence rates are, of course, dependent on the questions asked in the study. The hallucination questions in the PSQ follow a series of questions assessing the possibility of psychosis and may be perceived in this context, reducing respondents' willingness to endorse them. Thus, the stigma associated with mental illness, particularly psychosis, may well reduce the extent to which people self-report. In addition, the first question asks about the occurrence of unusual visual and auditory experiences on more than one occasion (‘Have there been times when…’), and the second question only probes for auditory verbal hallucinations (… ‘hear voices saying quite a few words or sentences…’). Hence, respondents may not have reported experiences that occurred infrequently or that they considered irrelevant to the question. The data reported by Tien (Reference Tien1991) were obtained using the broader NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS; Reference Robins, Helzer and CroughanRobins et al, 1981). Assessment of hallucinations began with a general symptom question: ‘Have you ever had the experience of seeing/hearing something or someone that others who were present could not see/hear?’ Positive responses were followed by structured probe questions that inquired about the nature, cause and consequences of these experiences.

Hallucinatory experiences were most commonly reported by 16— to 19-year-olds and the age distribution was similar to that for auditory hallucinations in the Tien study. There were similar prevalence rates for men and women in this White sample, which contrasts with higher rates of hallucinations reported by women in previous studies (Reference Sidgewick, Johnson and MyersSidgewick et al, 1894; Reference TienTien, 1991), although females reported more hallucinatory experiences than males in the Caribbean sample.

Variation across ethnic groups

Reports of hallucinations varied significantly across ethnic groups, with the highest rates in the Caribbean group (9.8%) and the lowest in the South Asian group (2.3%). The ethnic differences in prevalence rates raise the possibility of cultural differences in the experience and reporting of hallucinations and are in accordance with previous reports of cultural variation in hallucinatory experiences (Reference Al-IssaAl-Issa, 1977; Reference Slade and BentallSlade & Bentall, 1988). In a similar epidemiological study, Schwab (Reference Schwab1977) found that Black Americans reported a higher frequency of hallucinations than White respondents, but there was a strong association with religious affiliation in that sample.

There was no effect of migration on the occurrence of hallucinations in the Caribbean group, but non-migrants reported significantly higher rates of hallucinations in the South Asian group. A likely explanation for the low prevalence rate in South Asian migrants was the poorer understanding of the questions in this group. Although the research method was designed to overcome linguistic difficulties (the interviews were conducted by ethnically matched interviewers in the language of the respondent's choice), the ideas contained in the questions may have been unfamiliar to people from a different cultural or linguistic background, making the measures less reliable for those more distant from Western culture (Reference Berthoud and NazrooBerthoud & Nazroo, 1997; Reference NazrooNazroo, 1997).

Hallucinations and mental health problems

These data are consistent with the view of a continuum of psychotic phenomena in the general population. Of the respondents who answered positively to the first hallucination item on the PSQ, less than half endorsed the second question as well and half reported another item on the PSQ. Of those who reported hallucinatory experiences, only a small percentage (about 11% in the White group) reported a diagnosis of psychosis or treatment for psychosis. This percentage was lower in the Caribbean group (2%), showing an increased discrepancy between the prevalence of PSQ hallucinatory experiences and reported psychosis diagnosis in this sample. Of those respondents who screened positive on the PSQ hallucination questions (i.e. those who endorsed both questions and were followed up), 25% met the PSE criteria for a psychotic disorder. This was consistent across ethnic groups. Interestingly, about half of those who were positive on the PSQ hallucination criterion but who did not meet the PSE criteria for a psychotic disorder met the criteria for a neurotic disorder.

Ethnicity and psychosis

The variation in hallucinatory experiences according to ethnic group is consistent with the main survey findings of ethnic differences, but the results are not in agreement with other studies on ethnicity and psychosis. The higher rate of hallucinations in the Caribbean group seems to be consistent with reports of higher rates of schizophrenia and other psychoses in African—Caribbean people (Reference Wesseley, Castle and DerWesseley et al, 1991; Reference van Os, Castle and Takeivan Os et al, 1996). However, Caribbean females reported more hallucinatory experiences than males in this study, whereas increased psychosis rates have been associated with both African—Caribbean males and females. The Fourth National Survey of Ethnic Minorities did find a higher rate of psychosis for Caribbean women, although this was not statistically significant and there was no difference for men (Reference NazrooNazroo, 1997).

The similar prevalence of hallucinations in Caribbean migrants and non-migrants corresponds with the findings of the Fourth National Survey of no difference in psychosis rates between these two groups (Reference NazrooNazroo, 1997), but the results are not consistent with reports of increased rates of psychosis in second-generation African—Caribbean immigrants (Reference McGovern and CopeMcGovern & Cope, 1987; Reference Harrison, Owens and HoltonHarrison et al, 1988). The contradiction between the Fourth National Survey findings on prevalence in the community and other studies of incidence leading to hospital admission is discussed in Nazroo (Reference Nazroo1997), Berthoud & Nazroo (Reference Berthoud and Nazroo1997) and Nazroo (Reference Nazroo1998). The relationship between ethnic variation in the experience of hallucinations and the presence of psychotic disorders is unclear. It has been argued that a lack of awareness of cultural differences in hallucinations and other ‘psychotic’ phenomena can lead to patients from ethnic minority groups being misdiagnosed as suffering from schizophrenia (Reference ShashidharanShashidharan, 1993). On the other hand, studies have shown that elevated rates of psychosis in African—Caribbean people are not due to misdiagnosis (Reference Lewis, Croft-Jeffereys and DavidLewis et al, 1990; Reference Hickling, McKenzie and MullenHickling et al, 1999). This survey suggests that, for all ethnic groups, self-reports of hallucinations are not invariably associated with mental health problems.

Continuum of hallucinations

Reports of hallucinatory experiences in the general population provide additional evidence that psychosis is on a continuum with normality. Cognitive psychological models have attempted to explain how anomalous experiences are transformed into psychotic symptoms (Reference Gaiety, Kuipers and FowlerGaretyet al, 2001). It is suggested that disruption of normal cognitive processes leads to anomalous conscious experiences. These experiences, often puzzling and associated with emotional changes, can seem personally relevant and trigger a search for explanation as to their cause. Biased conscious appraisal processes contribute to a judgement that these confusing experiences (which may feel externally generated) are, in fact, externally caused. Thus, a tendency to form abnormal beliefs may be a crucial factor in generating psychotic hallucinations. It may be possible also that delusional descriptions arise when there is no ready alternative explanation and the hallucinatory experience does not fit into a shared cognitive or cultural framework.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• The continuum view of psychotic experiences is less stigmatising than traditional categorical approaches.

-

• The higher rates of hallucinations reported by Caribbean people are not associated with increased rates of psychosis.

-

• Ethnic differences in the experience of hallucinations should be taken into account when diagnosing psychiatric disorders.

LIMITATIONS

-

• The Psychosis Screening Questionnaire (PSQ) items are intended to screen for hallucinations and do not provide data on the precise nature or context of the hallucinatory experiences.

-

• Not all respondents were asked about psychiatric diagnosis and not all those who screened positive on PSQ were followed up with the Present State Examination (PSE), although non-random effects are unlikely.

-

• Low ratings of hallucinations on the PSE may be due to interviewers disregarding hallucinatory experiences in people whom they did not see as psychotic.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.