There is little question that binary polemics dominated elite-level contestation. But did these polemics shape the common-sense understandings of ordinary Malaysians? This chapter turns from the political spectacle to popular legal consciousness. I draw on open-ended interviews, focus group discussions, and original survey data to explore how everyday Malaysians understood the Article 121 (1A) controversies and what they meant for the future of their country. The data suggests that the cases were perceived in starkly different terms across Malaysia’s ethnic and religious “legalscape.” Despite divergent understandings of the cases, however, most Malaysians were united in the assumption that legal tensions were inevitable, and a concrete manifestation of a basic incompatibility between Islam and liberalism. The second part of the chapter turns to the efforts of Sisters in Islam, a Malaysian non-governmental organization that challenges these binary constructions and works to expand women’s rights from within the framework of the Islamic legal tradition. I examine the unique strategies that Sisters in Islam undertakes to confront the rights-versus-rites binary, which is now deeply entrenched in the popular imagination.

Rights-versus-Rites in Popular Legal Consciousness

To examine the hold of the rights-versus-rites binary in popular legal consciousness, I assembled a multiethnic research team to conduct one hundred semi-structured interviews with ordinary Malaysians.Footnote 1 These interviews were supplemented by a nationwide survey with a sampling frame that ensured a maximum error margin of ±3.03 percent at a 95 percent confidence level.Footnote 2 Finally, a series of focus groups were convened.Footnote 3 All three sets of data suggest that popular legal consciousness closely aligned with the rights-versus-rites binary advanced by political activists and further amplified by the media.

As we saw in Chapter 5, conservative organizations frequently claimed that the Article 121 (1A) cases represented deliberate attempts to undermine Islam and the shariah courts. These claims appear to have resonated with the public. Sixty-two percent of Muslims surveyed believed that the Article 121 (1A) cases were “examples of efforts by some individuals and groups to undermine Islam and the shariah courts in Malaysia.” By way of comparison, only eight percent of non-Muslims viewed these cases as efforts to undermine the shariah courts. Muslim respondents almost all spoke of Islam being “the religion of the country” and most expressed the view that the Muslim community must be allowed to govern its own affairs without interference from the civil courts. The Article 121 (1A) cases and the controversies that surrounded them were not understood as the result of the tight regulation of religion. Instead, many understood the legal controversies as the result of too little regulation and bold attempts by non-Muslims to undermine the position of Islamic law in the country. One respondent explained that legal disputes come about “because we don’t have full implementation of the shariah law here in Malaysia.” He clarified that, “we claim that we are an Islamic country but our shariah law is still not that strong. If we don’t strengthen shariah law, we will be weakened and they [non-Muslims] will be able to overrule us [Muslims] using the civil court.”Footnote 4 This view, which was reflective of the mindset of many in the Malay community, pointed to an immediate threat, a diagnosis of the problem, and a solution. The immediate threat is that non-Muslims “will be able to overrule us.” The diagnosis of the problem is that “shariah law is still not that strong.” And the solution to the problem is “full implementation of shariah law.”Footnote 5 This “Islam under siege” threat perception matched the frames of understanding provided by the most outspoken conservative activists and nongovernmental organizations virtually one-to-one.

Muslim respondents also had a strong tendency to understand the shariah courts as faithful expressions of Islam, unmediated by human agency. Concerning the Lina Joy case, for example, respondents explained that the government must stringently regulate apostasy because it is forbidden in Islam. Three-quarters of Muslim respondents believed that Joy should be barred from changing her official religious status without the permission of the shariah court. In the national survey, an even greater majority, 96.5 percent, stated that Muslims should not be permitted to change their religion. Rather than drawing popular attention to the variety of possible positions concerning apostasy in the Islamic legal tradition, the polarized framing around the case appears to have strengthened a view that the state is obliged to prevent apostasy. Similarly, most Muslim respondents understood the child custody cases of Gandhi v. Pathamanathan and Shamala v. Jeyaganesh in religious terms.Footnote 6 Although viewed as regrettable by many, Gandhi’s loss of custody was considered the only acceptable outcome.

It is nonetheless important to note that Muslim respondents were not uniform in their understanding of the cases. When asked about Gandhi v. Pathamanathan in the open-ended interviews, nearly one-third of Muslim respondents held that Gandhi’s husband should not have the legal right to convert the children without his wife’s approval. One-third also shared the view that the civil court was the proper forum to address the dispute, not the shariah court. Similarly, one-fifth of Muslim respondents argued that Lina Joy had the right to change her religious status and that she should not be answerable to the shariah court. Muslim respondents who voiced these opinions tended to have a better understanding of the details of the cases, especially their legal ambiguities. Perhaps because of this, these respondents also tended not to view the cases as efforts by groups and individuals to challenge Islam and the shariah courts. This finding supports the hypothesis that the stylized narratives advanced in the Malay media tended to have less of an influence on respondents who understood the technical complexities that had triggered the Article 121 (1A) cases.

It is not surprising that non-Muslim respondents, on the other hand, viewed the cases through the prism of minority rights vis-à-vis the state and the Malay Muslim community. Every non-Muslim respondent believed that an injustice had befallen Gandhi when her husband sought child custody in the shariah courts. Like their Malay counterparts, non-Muslims did not attribute the outcomes to the ambiguities, contradictions, complexities of the Malaysian legal system, or the rigid regulation of religion. Rather, they associated the outcomes with a broader pattern of legal discrimination against non-Malays and non-Muslims. In discussions of Gandhi v. Pathamanathan, for example, respondents frequently commented on the economic advantages that Malay Muslims enjoyed at the expense of non-Muslim Indian and Chinese Malaysians. Respondents frequently vented their frustration that Malays enjoyed access to lucrative government contracts, discounts on housing, government scholarships for study at home and abroad, reserved spaces at universities, and many other benefits. In other words, the Article 121 (1A) cases were understood in relation to a whole array of longstanding political and economic grievances of the ethnic Indian and ethnic Chinese communities.

An elderly, ethnic Indian man whom I interviewed articulated the grievances that are common to many non-Muslims, while voicing nostalgia for an era when religious cleavages were less pronounced and state resources were distributed more equitably. After a lengthy discussion of several prominent Article 121 (1A) court cases, he explained that:

Thirty-five years back, we didn’t have these issues. Everyone was happy. I went to school with the Chinese and Bumis. We really mingled around. There was no problem. But now come a lot of issues. They are segregating the people. It is government policy that they’re segregating [us]. We didn’t have problems with our Muslim friends and our Chinese friends. No, we went to school, and we didn’t have problems. The Muslims can buy any property for thirty percent less. It’s another discrimination. Indians get good marks in school, but the Malays get the scholarships. It’s the government policy that is disuniting the people. These are the sort of things that people get fed up with.

At this point in the interview, I asked the respondent, “So are these [economic] issues more important than the court cases that we discussed earlier?” To which he replied, “Both are the same to me. Both are important.” The fact that the discussion of the court decisions naturally flowed into a discussion of economic, social, and political grievances illustrates the dynamic of “issue expansion” at work. Before the extensive media coverage of the Article 121 (1A) cases, ordinary Malaysians had little awareness of the legal tensions that were brewing in the courts. But after 2004, the extraordinary political spectacle around Lina Joy, Shamala Sathiyaseelan, and Moorthy Maniam made each of the cases household names. The cases became powerful metonyms for wider ethnic and religious grievances.

The cases were clearly at the front of people’s minds. Respondents were not only familiar with the cases, but some launched into a conversation about them before we had the opportunity to initiate discussion. For example, the first substantive interview question was “how do you see the state of religious and race relations in the country today?” Before we could proceed to the next question, many respondents offered detailed descriptions of the injustices suffered by Indira Gandhi and others, as examples to support their assessment of poor race and religious relations in Malaysia. Similarly, when asked about specific court cases, respondents frequently referenced other Article 121 (1A) cases that had also been covered heavily in the press, including Kaliammal v. Islamic Religious Affairs Council, Subashini v. Saravanan, and Shamala v. Jeyaganesh. The frequency of this cross-referencing suggests that these cases were salient in popular legal consciousness among “everyday Malaysians.”

Not surprisingly, non-Muslim Indian and Chinese respondents universally viewed the civil courts as the appropriate judicial forum to resolve legal controversies, even if they were skeptical that justice would be delivered. Whereas Malays viewed litigation as an attack on Islam and a threat to the autonomy of the shariah courts, non-Muslims experienced the cases as just another example of Malay Muslim dominance over religious and ethnic minorities. And just as most Muslim respondents understood the Article 121 (1A) cases as a threat to the Muslim community, non-Muslims viewed them as fundamental(ist) threats to their communities. The radiating effects of these court decisions varied starkly across ethnic and religious communities.

Beyond these differing threat perceptions, there were shared assumptions across ethnic and religious lines. The first shared assumption was that the cases were deeply consequential for the future of Malaysia, beyond the individuals involved and beyond the specific issues at hand, such as religious freedom. Eighty-five percent of Muslim respondents and eighty percent of non-Muslim respondents reported that they had strong views about the outcome of the cases. This is a striking confirmation of the broadening audience and the tremendous “expansion” of issues and concerns that were (made to be) associated with the cases. Media outlets and political activists had framed the cases to resonate with longstanding sensitivities and grievances, stirring passions across ethnic and religious lines. The cases effectively became metonyms for the most pressing social and political issues of the day, including fundamental questions of state identity and the contested foundations of the political order. The audience extended to the entire nation, with most everyone invested in the outcome.

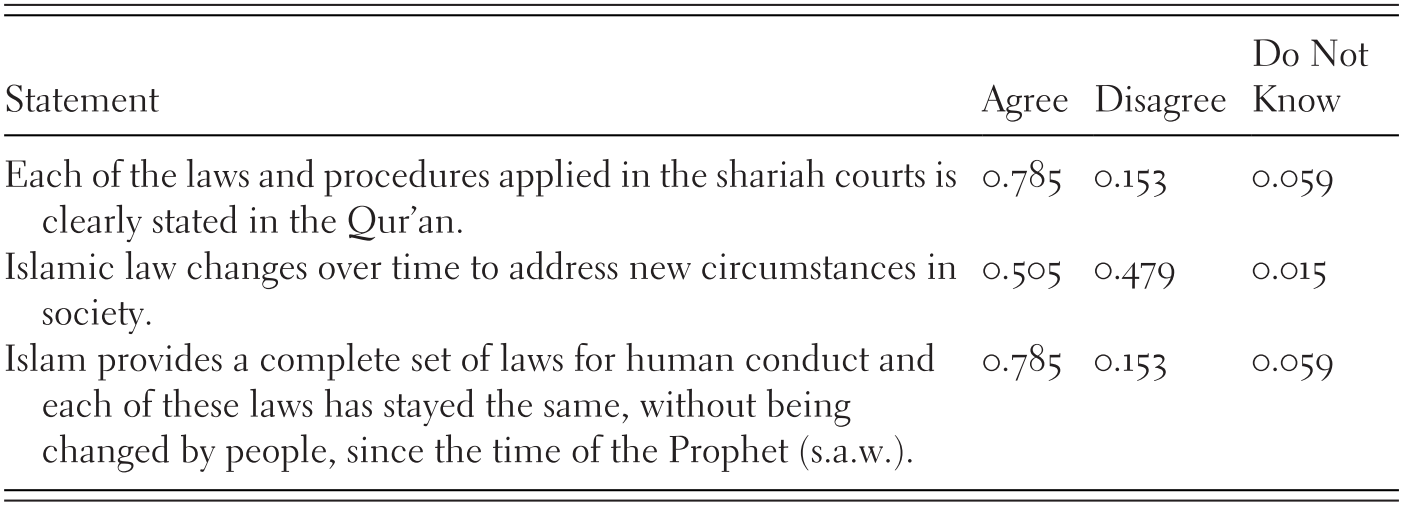

A second shared assumption was that the cases were the result of a fundamental incompatibility between Islam and liberal rights. In one of the most striking findings of the national survey, respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the statement: “Each of the laws and procedures applied in the shariah courts is clearly stated in the Qur’an.” 78.5 percent of respondents agreed, while only 15.3 percent disagreed (Table 6.1). As examined in Chapter 2, few of the substantive provisions and none of the procedures applied in the shariah courts are found in the Qur’an. The Islamic Family Law Act and parallel state-level enactments merely provide a codified and select representation of a diverse body of fiqh. An important consequence of codification is that, for many, Islam is equated with the law, and a legalistic understanding of Islam is elevated above all others. Islamic law is also understood as fixed. Respondents were almost equally divided by the statement “Islamic law changes over time to address new circumstances in society,” with only slightly more respondents agreeing (50.5 percent) than disagreeing (48 percent). As previously explained, the idea that Islamic law evolves with new understandings and in new contexts is a core concept in Islamic legal theory. Yet those surveyed were divided in evaluating the statement. The next statement approached the issue in a more direct and strongly worded fashion: “Islam provides a complete set of laws for human conduct, and each of these laws has stayed the same, without being changed by people, since the time of the Prophet (s.a.w.).” An overwhelming 82 percent of respondents agreed with the statement, a remarkable result given that human agency is acknowledged as being central to the development of Islamic law among Muslim jurists.

| Statement | Agree | Disagree | Do Not Know |

|---|---|---|---|

| Each of the laws and procedures applied in the shariah courts is clearly stated in the Qur’an. | 0.785 | 0.153 | 0.059 |

| Islamic law changes over time to address new circumstances in society. | 0.505 | 0.479 | 0.015 |

| Islam provides a complete set of laws for human conduct and each of these laws has stayed the same, without being changed by people, since the time of the Prophet (s.a.w.). | 0.785 | 0.153 | 0.059 |

For both Muslims and non-Muslims, the shariah courts were understood as embodying “shariah law.” Malaysians were therefore primed to assume that jurisdictional scuffles are part of a zero-sum struggle for or against the “implementation” of Islamic law. In these circumstances, Islam is pitted against liberal rights, individual rights are pitted against collective rights, and religion against secularism. These binaries elevate the “legal-supremacist” conceptualization of “Islam as law” and they further position Anglo-Muslim law as the full and exclusive embodiment of the Islamic legal tradition (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2016). Indeed, most political discourse is premised upon this stark binary.

Another question on the nationwide survey probed the salience of these binary formations. Respondents were asked to consider the question, “Are the Federal Constitution and the shariah compatible or incompatible with one another?” 45.5 percent responded that they are incompatible, 44.9 percent responded that they are compatible, and 9 percent said they “do not know.”Footnote 7 Those respondents who viewed the Constitution and the shariah as incompatible were asked the follow-up question, “Should one of these be a final authority above the other?” Here, a remarkable 80.2 percent responded that the “shariah” should be the final authority.Footnote 8 These findings hint at the effect of the binary tropes that have circulated in the media for years in Malaysia. These popular understandings pose significant challenges to the perceived legitimacy of the Malaysian legal order. Moreover, because Islam is used as an instrument of public policy, these beliefs carry important implications for a host of substantive issues. Women’s rights provide an important example. When the public believes that the shariah courts apply God’s law, unmediated by human agency, people who question or debate those laws are easily framed as working to undermine Islam. Indeed, it is the presumed divine nature of the laws applied in the shariah courts that provides the rationale for criminalizing the expression of alternative views in the Shariah Criminal Offenses Act. As a further result, laws concerning marriage, divorce, child custody, and other issues critical to women’s well-being are difficult to approach as matters of public policy.

The salience of the rights-versus-rites binary was also evident in many of the open-ended interviews. In the discussion of the Lina Joy case, for example, one respondent explained, “she says that she is exercising her human rights, but here in Malaysia our official religion is Islam.” When asked to elaborate, the respondent suggested that Islam and liberalism were incompatible and that the appropriate resolution to the tension would be “to just use shariah law in Malaysia [and get rid of civil law].”Footnote 9 Another respondent explained that:

The shariah court is submissive to the civil court. When anything is deferred to the civil court, the civil court wins, and the shariah court loses. [This shows that] we don’t put Islam first; we put the constitution first. If you ask me what the solution is, I have to say it’s the shariah court and shariah law because these things [Islamic fundamentals] you can’t change. You can amend a constitution. It’s passed on your whim and fancy. But the Qur’an you cannot change. If it’s “A” today, it’s going to be “A” until the end of the day. But for the constitution, if you have “A” today, and you have two-thirds majority, it can be “B”.Footnote 10

Echoing the same binaries that are played out in the media, many of the respondents explained that Islam and liberal rights are locked in opposition. When it comes to the Article 121 (1A) cases, self-identified secularists and Islamists understand themselves as pitted against one another. They are united by the perception that they are locked in a zero-sum struggle between the “implementation” of Islamic law vs. civil law.Footnote 11

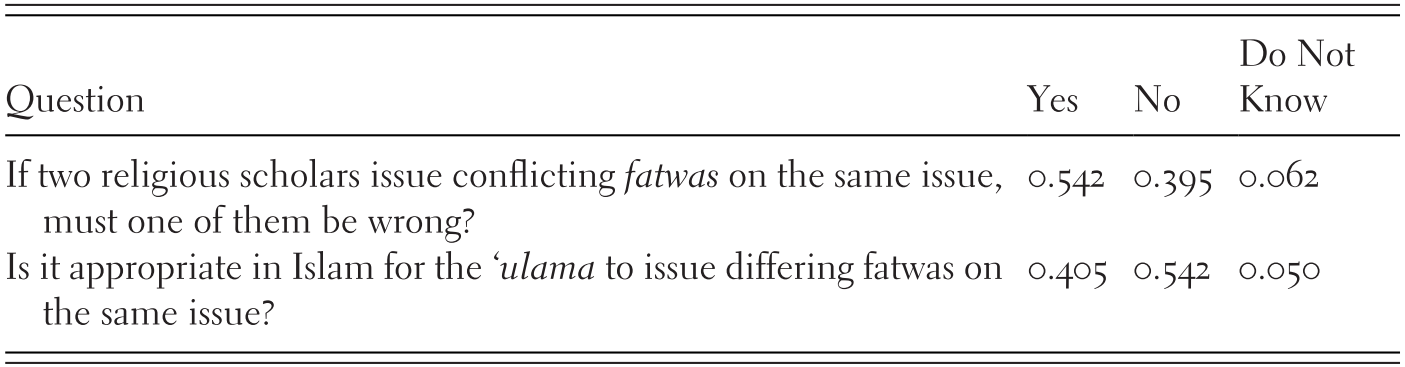

Another set of survey questions probed whether Malaysian Muslims conceive of Islamic law as uniform in character, with a single “correct” answer to any given issue or, alternatively, whether the Islamic legal tradition provides a framework through which Muslims can arrive at equally valid yet differing understandings of God’s will. One way of approaching this issue was to assess popular understandings of the fatwa. As detailed previously, a fatwa is a non-binding opinion by a religious jurist. It is widely accepted among Sunni legal scholars that for any given question, jurists are likely to arrive at a variety of views, all of which should be considered equally valid if they follow the accepted methods of one of the four schools of jurisprudence. But do lay Muslims understand fatwas in the same way?

To explore this issue further, respondents were asked, “If two religious scholars issue conflicting fatwas on the same issue, must one of them be wrong?” The majority (54.2 percent) answered yes, while 39.5 percent answered no. In one sense, this majority response is in harmony with Islamic legal theory; most scholars believe that there is a correct answer to any given question, but that humans can never know God’s will with certainty in this lifetime. However, in another survey question, the same respondents were asked: “Is it appropriate in Islam for the ‘ulama to issue differing fatwas on the same issue?” On this question, 40.5 percent answered yes while the majority, 54.2 percent, answered no. Taken together, the responses suggest that most respondents believe that there is a single “correct” answer for any given issue and that religious scholars can and should arrive at the same answer in the here and now. In other words, most lay Muslims tend to understand Islamic law as constituting a single, unified code rather than a body of equally plausible juristic opinions (See Table 6.2).

Table 6.2 Uniformity or plurality of Islamic law in popular legal consciousness

| Question | Yes | No | Do Not Know |

|---|---|---|---|

| If two religious scholars issue conflicting fatwas on the same issue, must one of them be wrong? | 0.542 | 0.395 | 0.062 |

| Is it appropriate in Islam for the ‘ulama to issue differing fatwas on the same issue? | 0.405 | 0.542 | 0.050 |

The finding that most lay Muslims understand Islamic law as a legal code yielding only one correct answer to any given question is a testament to how the modern state, with its codified and uniform body of laws and procedures, has left its imprint on popular legal consciousness. Only about 40 percent of respondents conceive of the possibility that two or more religious opinions can be simultaneously legitimate, a remarkable divergence from core axioms in Islamic legal theory. Whereas Islamic jurisprudence is diverse and fluid, it is understood by most Malaysians as singular and fixed. Implementation of a codified version of Islamic law through the shariah courts is assumed to be a religious duty of the state. And, indeed, it appears that most Malaysians believe that the shariah courts apply God’s law directly, unmediated by human agency.

When public policy is legitimized through the framework of Islamic law, this vision of Islamic law as code narrows the scope for debate and deliberation. It is no wonder that women’s rights activists have encountered such difficulty in mobilizing broad-based public support for their effort to reform Muslim family law codes. It is also not surprising that they often find themselves on the losing end of debates with conservatives. Women’s rights activists, even those operating within the framework of Islamic law, are easily depicted by their opponents as challenging core requirements of Islamic law, or even Islam itself. Conversely, the discursive position of conservative actors is strengthened. Religious officials, political parties, and other groups wishing to preserve the status quo can easily position themselves as defenders of the faith.

This can be seen in other areas as well. Islamic law is used as the pretext for outlawing “deviant” sects, policing public morality (Liow Reference Liow2009: 128–31), and curtailing freedom of expression (SUARAM 2008, 69–71).Footnote 12 In each of these areas, Islamic law is not only cast in a conservative vein; it is also deployed in a manner that shuts down public debate and deliberation. This vision of Islamic law is encouraged by the government, the growing religious bureaucracy, the Islamic Party of Malaysia (Parti Islam se-Malaysia, or PAS), and Islamist organizations such as ABIM (Liow Reference Liow2009; Mohamad Reference Mohamad2010). Such rhetorical positioning is regularly deployed in public policy debates because speaking in God’s name proves to be the most effective and expedient avenue for a variety of state and non-state actors to undercut their opponents.

Overcoming Binaries: The Work of Sisters in Islam

The data presented in this chapter confirms what women’s rights activists have long known: the state’s selective codification of Islamic law is understood by many as the faithful implementation of divine law. Because of this conflation, rights activists cannot easily question or debate family law provisions without being accused of working to undermine Islam. The Malaysian women’s rights organization Sisters in Islam identifies this rights-versus-rites binary as a formidable obstacle. Sisters in Islam co-founder Zainah Anwar explains, “Very often Muslim women who demand justice and want to change discriminatory law and practices are told ‘this is God’s law’ and therefore not open to negotiation and change” (2008b, 1). These informal obstacles underline the critical importance of “legal consciousness.”

Sisters in Islam has a unique approach to overcoming the rights-versus-rites binary in popular legal consciousness.Footnote 13 Instead of pursuing a strictly secular mode of political activism, it engages with liberal rights constructs and the Islamic legal tradition simultaneously with apologies to no one. Sisters in Islam insists that there is no contradiction whatsoever in being a committed Muslim and a committed liberal because core values of justice and equality are inherent to Islam. It takes aim at the laws governing marriage, divorce, and other aspects of Muslim family law that have been codified in a manner that provides women with fewer rights than men. Along with a rising number of Muslim feminists, it insists that the Islamic legal tradition is not inherently incompatible with contemporary notions of liberal rights. It explains that existing inequities are reflective of the biases and shortcomings of human agency, not core values of Islam. Instead of working to abolish religion in the public sphere, Sisters in Islam works to recover the core spirit of justice and equality in Islam. It explains that the Islamic legal tradition is not a uniform legal code but is instead a diverse and open-ended body of jurisprudence that affords multiple guidelines for human relations, some of which are better suited to contemporary circumstances.

This is a new mode of political engagement. While women’s rights initiatives were advanced through secular frameworks through most of the twentieth century, efforts to effect change in family law from within the framework of Islamic law have gained increasing traction in recent years. To varying degrees, women have pushed for family law reform within the framework of the Islamic legal tradition in Egypt (Singerman Reference Singerman2005; Zulficar Reference Zulficar, Quraishi and Vogel2008), Iran (Mir-Hosseini Reference Mir-Hosseini, Quraishi and Vogel2008), Malaysia (Azza Basarudin Reference Basarudin2016; Nik Noriani Nik Badlishah Reference Badlishah2003, Reference Badlishah, Quraishi and Vogel2008; Norani Othman Reference Othman2005), Morocco (Salime Reference Salime2011), and many other Muslim-majority countries. This opens a new terrain for debate and dialogue. In some cases, this strategy yields concrete, progressive legal reforms. Among all the women’s groups operating in this mode of engagement, Sisters in Islam has been a pioneer in these endeavors since its establishment in 1987.

As a central part of its message, Sisters in Islam invokes the core conceptual distinction between the shariah (God’s way) and fiqh (human understanding). As examined in Chapter 2, Islamic legal theory regards the shariah as immutable, whereas fiqh is the diverse body of legal opinions that are the product of human reasoning and engagement with the foundational sources of authority in Islam, the Qur’an, and the Sunnah. In this dichotomy, God is infallible, while humankind’s attempt to understand God’s way is imperfect and fallible. Islamic legal theory holds that humans should strive to understand God’s way, but that human faculties can never deliver certain answers; people can only reach reasoned deductions about what God’s will might be. To be sure, jurists in the classical era did not use the specific terms “shariah” and “fiqh,” but they recognized these conceptual distinctions nonetheless.

The conceptual distinction between God’s perfection and human fallibility is of critical importance because it serves as the basis for a normative commitment within Islamic legal theory toward respect for diversity of opinion as well as temporal flexibility in jurisprudence. Since the vast corpus of Islamic jurisprudence is the product of human agency, scholars of Islamic law recognize Islamic jurisprudence as open to debate and reason and subject to change as new understandings win out over old. By invoking the shariah/fiqh distinction and the open-ended jurisprudential tradition within Islam, Sisters in Islam engages conservatives on their own discursive terrain. The common rebuke that women’s rights activism challenges “God’s law” is met with the powerful rejoinder that Islam simply does not have a single position on most issues.

To overcome the rights-versus-rites binary in popular legal consciousness, Sisters in Islam conducts a variety of public education programs with the central purpose of highlighting the distinction between shariah and fiqh. This entails a number of interrelated strategies, all of which are meant to disrupt and critique the state monopoly on religious knowledge production, spur new knowledge production, and provide alternatives that empower women while nonetheless remaining faithful to the Islamic legal tradition. These strategies include the commissioning of detailed studies of various issues pertaining to women’s rights in the Islamic legal tradition (e.g., polygamy, domestic violence, marriage, and divorce); producing and distributing question and answer booklets concerning various aspects of gender in Islam; documenting the “lived realities” of Muslim family law on Malaysian women; drawing attention to more progressive formulations of Muslim family law in other Muslim-majority countries; penning regular columns and op-eds in major newspapers; organizing reading groups and study sessions; running a telephone hotline for women in need of legal assistance; and, increasingly, engaging with the issues of the day in real time via digital and social media. Sisters in Islam also organizes intensive, multi-day training sessions for journalists, lawyers, human rights activists, women’s groups, and even government officials and members of parliament. Each of these workshops provides a crash course on the fundamentals of usul al-fiqh, on Muslim family law and shariah court administration in Malaysia, and the possibilities for progressive legal change within the framework of Islamic law. By training journalists, lawyers, human rights activists, and government officials, Sisters in Islam is able to “scale up” its message through key actors, some of whom might otherwise reinforce the rights-versus-rites binary in their work.

Sisters in Islam runs an impressive operation with modest resources, yet it faces formidable obstacles. As examined in Chapter 2, the Malaysian state has significant legal and administrative infrastructure that is designed to monopolize religious knowledge production. The Administration of Islamic Law Act and parallel state-level enactments establish a monopoly on the administration of mosques, including the licensing, appointment, and disciplining of imams. Federal and state agencies also dictate the content of Friday khutbah. The reach of the state extends to other areas as well, including religious content in public education (Azmil Tayeb Reference Tayeb2018), state television and radio, quasi-independent institutions such as IKIM (Institute for Islamic Understanding), the shariah court administration, and state and federal fatwa councils. Between these various institutions, the government controls formidable resources for shaping popular understandings of Islam as fixed, singular, state-centric, and unmediated by human agency.

Sisters in Islam must also contend with legal challenges. The group might have been banned long ago were it not for its tenacity and the elite-level connections of a few of its members.Footnote 14 Most of the activities of Sisters in Islam are illegal by a straightforward reading of the Shariah Criminal Offenses Act and parallel state-level enactments. There have been periodic calls from conservative NGOs for the government to close Sisters in Islam. A lawsuit was initiated to bar it from using “Islam” in its title.Footnote 15 More concretely, one of its books was banned for several years until Sisters in Islam prevailed in litigation to lift the ban.Footnote 16 A still-unfolding case involves a fatwa issued by the Selangor Fatwa Committee that condemns Sisters in Islam for subscribing to “religious liberalism and pluralism.” The fatwa calls on the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commissions to ban and seize any publication that might be considered “liberal and plural” because of the threat it poses to Islam. Sisters in Islam contested the fatwa in High Court, but Justice Datuk Hanipah Farikullah dismissed the claim under the premise that the shariah courts have exclusive jurisdiction over the matter, as per Article 121 (1A). Sisters in Islam appealed the decision with a positive result. The Court of Appeal ordered another High Court judge to consider the merits of the case. To date, the issue has not reached a conclusion.

Sisters in Islam was not the only organization that was exploring new ways to engage ordinary Malaysians. Many of the activists who were at the forefront of litigation efforts readily acknowledged the limitations of depending exclusively on the courts to secure liberal rights. One of the most prominent attorneys litigating religious freedom cases over the last fifteen years, K. Shanmuga reflected on the frustrations that an exclusive reliance on litigation entailed.

The group of us who started the Centre are all primarily litigation lawyers, who slowly became disenchanted with the litigation process as a means of achieving real social change. This was a result of the bitter experiences in the majority of our public interest cases. Government lawyers came with technical and petty objections on procedure, which were upheld by judges reluctant to deal with the real subject matter of the controversy. International human rights protections were not respected and extensive arguments on them were summarily dismissed as being irrelevant and not binding in Malaysia. It was clear to us, then, that taking matters to court would never really solve real problems.

Haris Ibrahim, another prominent lawyer who had litigated many of the religious freedom cases, abandoned the law altogether and founded Saya Anak Bangsa Malaysia (SABM) in 2009.Footnote 17 Frustrated with the lack of headway in the courts, Haris sought to build a grassroots movement for social and political change. SABM was initiated with considerable fanfare, which included a nationwide “roadshow” (reminiscent of the Article 11 roadshow before it) with stops in Perak, Sabah, Sarawak, Terengganu, Kelantan, Pahang, Malacca, Kedah, and Penang.

Likewise, the Malaysian Bar Council launched a “MyConstitution Campaign” (“Kempen PerlembagaanKu”) in the same year as SABM. The campaign was billed as an effort to “educate and empower the rakyat and to create greater awareness about the Federal Constitution.”Footnote 18 The Bar Council developed a series of pocket-sized guides in easy-to-read language (with cartoon graphics and all) explaining the fundamental rights of citizenship guaranteed by the Constitution. The campaign focused on direct engagement with youth (particularly at schools and universities) and it heavily engaged with social media. Edmond Bon, one of the driving forces behind the MyConstitution Campaign, also founded the Malaysian Centre for Constitutionalism and Human Rights (MCCHR) with Long Seh Lih in 2012. Like the MyConstitution Campaign, the MCCHR focused its energy on the next generation of legal activists. It opened a resource center and organized workshops, conferences, and training sessions on strategic litigation in the service of liberal rights advocacy.

A related initiative, the LoyarBurok blog, was founded by six young lawyers, including Edmond Bon, Long Seh Lih, and two lawyers who worked extensively on freedom of religion cases, K. Shanmuga and Fahri Azzat.Footnote 19 “LoyarBurok” literally means “bad lawyer” and is slang in Malaysia for a person who is full of hot air. The humor in the title captures the irreverent tone that characterizes the outlet. Yet the purpose is anything but frivolous. LoyarBurok is meant to generate informed debate at the intersection of law and politics. More fundamentally, LoyarBurok aims to inspire legal mobilization in the service of social and political change. The blog serves as a repository of court decisions, case notes from key legal battles, analysis of select judgments, and perspectives on the latest round of public interest litigation.

All of these organizations, in their own way, are working to elevate and galvanize popular legal consciousness. If there is any hopeful note to be found, it is the fact that a variety of organizations, working through both secular and religious discourses, have joined together for progressive change. This is particularly manifest in the work of the Joint Action Group for Gender Equality (JAG), a coalition of seven women’s rights groups, including Sisters in Islam, that has worked together since 1985.