Introduction

This article addresses the transition from forced to voluntary labour in the construction and maintenance of infrastructure in rural Africa during the colonial period. The literature revolves around the role of the Forced Labour Convention of 1930 in triggering this transition, and agrees that, prior to this, forced labour was ubiquitous. Van Waijenburg estimates that before France's ratification of the Convention in 1937, the contribution of forced labour in French colonies represented nearly half of government revenue in 1913 and 1920, and one quarter in 1929 and 1934.Footnote 1 There are no similar estimates for British colonies, but in the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), Nigeria, and Kenya, men were liable to work up to twenty-four days annually, while in French colonies the maximum was fifteen days. This suggests that forced labour was no less prevalent in British colonies and that its major or minor share in government revenue depended on the availability of other sources of revenue, especially on the existence of overseas trade.

The role of forced labour was not limited to compensating for a lack of revenue: forced labour underpinned the unequal power relations that characterized colonial societies, and for that reason, it was prevalent even in regions that generated considerable revenue.Footnote 2 Akurang-Parry argues that in the south of the Gold Coast, the richest region of this prosperous colony, any movement away from forced labour came from outside the colony and was a result of the mounting pressure exerted by international organizations on the colonial government.Footnote 3 The following pages focus on the poorest region of this colony, the Protectorate of the Northern Territories. As in most of colonial Africa, roads in the Northern Territories were almost the only public infrastructure and were considered essential for its economic development. But unlike the southern area of the Gold Coast, which became the world's largest cocoa exporter by 1911, none of the so-called cash crops took off, enormously complicating the financing of roads and increasing the incentives to resort to compulsion. These stringent conditions make this protectorate an ideal setting to build on the existing literature, focusing on how the colonial administration responded to international organizations’ efforts to end forced labour. However, this article takes an altogether different approach, focusing instead on the role played by local conditions in triggering the transition to voluntary labour. It also explores the evolving significance of roads for those who constructed, maintained, and used them, particularly concerning the spread of lorries.

The literature on colonial Africa has stressed the reproduction of compulsory practices through subtle adaptations to the changing environment. Efforts have concentrated on elucidating the strategies that local chiefs and colonial administrations followed to counter the potential effects of the Forced Labour Convention of 1930. Cooper has argued that the most immediate outcome was that British and French colonial administrations distanced themselves from the direct recruitment of forced labour, leaving that responsibility to local chiefs. It was only after World War II, when metropoles increased their subsidies for development and party politics emerged, that forced labour on public works really came to an end.Footnote 4

More recent literature points to greater continuities in the use of forced labour and a more active involvement of colonial administrations in making them possible. Keese argues that chiefs and colonial administrations on the ground exploited loopholes in international legislation, so that forced labour remained a possibility even beyond the colonial period.Footnote 5 Okia has focused on the most glaring loophole: communal labour or the labour that local chiefs were entitled to require in the interest of the community. This type of labour was condoned by humanitarian organizations as “traditional” and was excluded from the definition of forced labour in the Convention of 1930. Therefore, as international legislation foreclosed other alternatives to unpaid labour, its meaning was stretched in such a way that forced communal labour became recurrent in large-scale projects in Kenya.Footnote 6 Likewise, Kunkel claims that the British introduced indirect rule in the Northern Territories to allow the chiefs to use forced communal labour on secondary roads once the Convention came into effect.Footnote 7 To approach the issue of continuities after the Convention, this article focuses on Kunkel's argument of indirect rule as a “hidden strategy” to continue with forced labour. In particular, I explore whether a consensus existed for the implementation of such a complex strategy or, on the contrary, whether forced labour was a contested issue that was being challenged from within and that the movement away from forced labour began earlier than the existing literature assumes.

The role of post-World War II development plans in triggering shifts in labour relations has also been questioned. Rossi has called attention to the fact that the demise of the political legitimacy of forced labour coincided with the rise of development discourse. She contends that colonial governments simply relabelled forced labour “voluntary work” and forced workers as “participants” to make the use of unpaid or underpaid labour more acceptable.Footnote 8 Wiemers, in her article on the first development plans in the Northern Territories in the 1920s and 1930s, highlights the roads constructed by “chiefs’ own initiative”. She argues that local chiefs constructed these roads using forced labour to pursue their personal interests. In parallel, colonial officials started using chiefs’ ability to raise unpaid labour as the main criterion to grant funds, prefiguring the dynamics of post-World War II development plans in which the “voluntary” participation of the community became a requisite.Footnote 9

Wiemers's interpretation stands in marked contrast with the well-documented construction of roads by farmers in cocoa areas.Footnote 10 This literature stresses the misguided colonial transport policies and the entrepreneurship of cocoa farmers who led the lorry revolution. A closer look at the roads in the north, however, calls into question such a contrast because these initiatives coincided with the spread of lorries into the rural north. This article approaches the roads constructed by local initiative as material culture that offers a rare window into rural populations’ views on public infrastructure, posing crucial questions to the academic literature on forced labour.

The article follows a generally chronological order, but each section centres on a relevant aspect of the transition to paid voluntary labour as the dominant form of labour on roads. The first section focuses on the initial decades of colonization after the labour tax was imposed in the Northern Territories, drawing attention to the numerous problems that this system entailed; these problems opened up opportunities to other forms of labour and paved the way for subsequent changes. The ensuing three sections focus on a different type of road because shifts in labour relations largely depended on who was in charge of roads. The second section deals with the roads under the purview of the Public Works Department (PWD), a branch of the central government, in which the first shift occurred: the transition from paid forced labour to paid voluntary labour. The third section focuses on district roads, which were the most affected by the implementation of indirect rule, and the transition from unpaid forced labour to paid voluntary labour. Finally, the fourth section deals with the roads constructed and maintained by local populations, which I term “people's roads”. My material sheds light on a question that the literature on cocoa areas still has not addressed: what happened to these roads over time? This long-term perspective illuminates a central shift in labour relations: the transformation of voluntary labour from unpaid to paid. Behind it was a profound change in the populations’ perceptions of their role and the state's role in road provision.

Although Wiemers and Kunkel comment on the difficulty of documenting forced labour in the Northern Territories after indirect rule was implemented and native authorities (chiefs) became responsible for roads, in practice the district commissioner continued to manage roads because native authorities were understaffed and lacked experience. In addition, all the budgets and accounting reports that native authorities had to prepare were supervised by district commissioners. Thus, there is abundant information about roads in the public records of Ghana, even for the period of indirect rule. The article also draws on interviews and fieldwork that I conducted between 2014 and 2016 to document a large migration of northern food farmers to the southern part of Ghana's yam belt, which began in the first decade of the twentieth century and continued throughout the whole century (Figure 1). When I conducted the research, the oldest people it was possible to interview belonged to the generation that was approximately in their twenties when direct taxation was introduced in 1936 (men's ages could be reasonably estimated because men were targeted by the system of district quotas for forced enlistment during World War II).Footnote 11

Figure 1. Map with the yam belt and the main sites cited in this text.

The Limits of the Labour Tax

After the annexation of the Northern Territories in 1902, the British colonial government promulgated a Roads Ordinance similar to existing legislation in the Colony, the coastal jurisdiction of the Gold Coast. It provided fixed quarterly payments not exceeding five shillings per mile for the maintenance of those roads listed on a schedule. Chiefs were entitled to these payments and could require all able-bodied men to work six days each quarter (twenty-four days per year). Disobedience incurred fines or imprisonment, but chiefs were also liable to pay a fine if the road was not in good repair.Footnote 12

The colonial administration conceived the Roads Ordinance as a sort of improvement: communities which had thus far maintained roads received advice from government, and chiefs obtained some remuneration for their efforts. However, the ordinance was never fully implemented because it overlooked important aspects that hindered its implementation. To begin with, the population was very unevenly distributed, and the most sparsely populated area was in the belt surrounding Ashanti, which any road linking the north and south of the colony was required to traverse. Population density in this area was as low as 1.2 persons per square mile and there were extensive swathes of completely uninhabited forest.Footnote 13 Furthermore, the ordinance established new standards for scheduled roads – eight to fifteen feet wide with a convex surface and a ditch on each side – that complicated their maintenance. These standards were supposed to better withstand rains and to facilitate travelling by horse and wheeled transport; however, for the local population or the existing caravan trade, their benefits were unclear: horses were too expensive and carts were feasible only for short distances during the dry season. Pressure to meet the new standards was initially put on communities by fining or imprisoning their chiefs, but it soon became evident that this tactic was a mistake because many chiefs did not control their populations, and this method only further undermined their authority.Footnote 14 The 1883 Gold Coast Native Jurisdiction Ordinance was revised in 1910, and new by-laws approved that reinforced chiefs’ power to punish those who refused to work and made the whole community – instead of chiefs – responsible for the fines imposed under the Roads Ordinance.Footnote 15

The Roads Ordinance substituted a labour tax for a tax known as the “maintenance tax”, which had been patchily collected until 1901.Footnote 16 The new labour tax met with the initial approval of colonial officials on the ground, and when the central government abolished the caravan tolls in the Northern Territories in 1909 and suggested introducing a poll tax, officials argued against it, pointing to the resistance of the population, a lack of staff for assessing and collecting the poll tax, and difficulty in checking chiefs’ abuses or in using the tax (cowries, goats, and the like) for administrative purposes. It was also feared that the poll tax might interfere with the labour tax without generating sufficient revenue to hire labour.Footnote 17 Yet, this unanimity vanished over time because the labour tax suffered from problems similar to those that had been cited for the poll tax.

Resistance by the population could be overt, such as when people simply refused to supply labour.Footnote 18 However, fines made other strategies preferable: in 1904, Soronasi, Kaka, Charandrai, and Dawadawa in Nkoranza were rebuilt between two and four miles away from the main road.Footnote 19 This move did not exactly exempt them from road work, but it helped hide potential labour. In the village of Namongbani – more than eighteen miles away from the administrative station of Yendi – elders instructed young people to run away when a white man approached. Because the instruction was never cancelled, several generations never met a commissioner.Footnote 20

The following two accounts suggest that the strategy of hiding labour was common but required the collaboration of chiefs to succeed. In August 1921, the food supply of the area within the triangle formed by Salaga, Kpandai, and Bimbilla was surveyed for a temporary camp of the Gold Coast Regiment. The area produced abundant food for the Salaga market, and the population expressed interest in selling food to the regiment, with farmers showing their farms and chiefs providing production estimates, but they were extremely vague about the number of inhabitants.Footnote 21 Data suggest that chiefs primarily under-reported the male population: according to the chiefs, there were 557 males and 760 females between the ages of sixteen and forty-five – a ratio of 1.36 females per male, whereas a decade later the ratio was 1.02 females per male.Footnote 22 Moreover, as Table 1 shows, the number of houses was at odds with the reported male population of this cohort: there were from 4.3 to 11.2 houses per male. There were other anomalies: for instance, the mounding of yams was a male task and, although it was rare for a farmer to grow more than 2,000 yams, ostensibly forty males at the village of Tale had farmed 250,000 yams in addition to large quantities of other crops.Footnote 23 The possibility that the low male population was due to seasonal migration for working on cocoa must be ruled out because such migration occurred between November and April. In addition, the Acting District Commissioner saw “hundreds of able-bodied persons” and thought that chiefs lied because the area had been controlled by the Germans until 1914, during which time the population had “suffered under the tyranny of the German administration”.Footnote 24

Table 1. Male population and number of houses in Kpandai area, 1921.

The second anecdote refers to the advent of motor transportation in Yendi in April 1920, which coincided with the Governor's visit. It attracted a large audience. In fact, the number of young men astonished colonial officials. Three months later, in response to a petition from Accra, the Chief Commissioner sent a request for 1,200 labourers to the District Commissioner of Yendi. The latter recalled the sparse population of the district and explained that the impressive gathering during the Governor's visit was because of the car: it had attracted men from the neighbouring French colony and no more than 600 labourers could be expected. However, the local chief revised this figure downwards to 200. He was also surprised by the crowds that met the Governor, but the majority of men came from the French colony and were not under his control.Footnote 25 In addition to illustrating how labour was negotiated within the colonial administration and with chiefs, the anecdote suggests that villages also manipulated the figures: although some individuals could have travelled from the neighbouring French colony, it is doubtful that the majority did. Importantly, it shows that the populations were aware of the news and the car aroused their curiosity, attracting to the public scene young men who did not exist according to colonial statistics.

Sloppy work was another form of resisting the labour tax. Unless tightly supervised, people cleaned “indifferently” or “according to the native ideas” instead of ditching and cambering.Footnote 26 In Kintampo, after much pressure, only one and a half miles of road had been cleaned, so the commissioner ended up using salaried porters.Footnote 27 The trenching of Salaga roads progressed under military supervision, but as soon as the military left, all work stopped.Footnote 28 Overseers began to be hired in the early 1910s to assuage these problems because the supervision of chiefs alone did not work as expected.Footnote 29

Rains and the fear of provoking a famine by interrupting the farming calendar limited the labour tax to the months between December and April, which coincided with the seasonal migration southwards.Footnote 30 District commissioners found that, often, only old people were available to work and that the labour tax fell disproportionately on those who remained and lived near roads.

Lack of technical expertise and knowledge of the area on the part of the district commissioners who designed improvements or new roads was also problematic. Cambers washed out, ditches bogged, bridges swept away, and culverts destroyed after “unusual” rains were recurrent events. On the whole, much labour power was wasted.Footnote 31 Commissioners were aware of this fact and petitioned for skilled labour, stone instead of wooden bridges and culverts, or paid gangs to maintain a minimum standard during rains to avoid starting the work almost from scratch every dry season. However, skilled labour had to be brought in from the south, the cost of cement or tools was higher in the north, and resources were always more limited.Footnote 32 Even local chief went frequently unpaid. The District Commissioner of Southern Mamprusi explained in 1927 that the Roads Ordinance had never been fully implemented because work concentrated on roads distant from villages, and money was spent on tools and skilled labour instead of paying chiefs. In Kusasi District, annual payments to all chiefs amounted to £19, an amount equivalent to only nineteen miles of road.Footnote 33

These difficulties opened avenues for paid labour, especially in towns where colonial stations were located and salaried porters could be used to do road work. Also, money or hoes were given to entice labourers to remain more than the six days per quarter stipulated by the ordinance.Footnote 34 Finally, on roads traversing unpopulated or sparsely populated areas, there were few other options than to hire labour. Workers received the same renumeration as porters: for example, in 1907, the salary for the Yeji–Burai road was twenty-five shillings (300 pence) a month and an attempt to reduce it to nine pence a day failed.Footnote 35

From a long-term perspective, the main effect of these difficulties was the erosion of administrators’ confidence in the labour tax as a rational system for constructing and maintaining a decent road network. The advent of lorries made things worse because their use required higher roads standards. Contrary to Wiemers's assertion that lorries negatively impacted the population because they increased the demand for forced labour, lorries, in fact, further highlighted the limitations of forced labour.Footnote 36 District commissioners attempted to solve part of these problems by organizing demonstrations of ditching, cambering, and cleaning, but the lack of tools and chiefs’ faulty supervision were real obstacles; even local initiatives for repairing culverts and bridges had to be discouraged as being dangerous for motor traffic.Footnote 37

Demonstrations, overseers, and an amendment to the Roads Ordinance in 1924 that substituted the six days each quarter with twenty-four days each year, were all attempts geared towards the rationalization of the system.Footnote 38 Until the mid-1920s, efforts concentrated on improving the quality of labour rather than increasing its quantity. There was, however, an important increase in compulsory labour during this initial period due to the drastic reduction of wages that converted paid labour into the main source of forced labour: wage reductions started in the late 1900s and, in less than a decade, they had been more than halved. That reduction affected especially porterage, since porterage was the most common form of paid labour, but it reverberated through the whole system because porters were drawn from the same population. It is unsurprising then that the first significant reversal in forced labour occurred in paid labour. It did not occur in porterage but rather in a relatively circumscribed part of the system of compulsory labour: the roads within the purview of the PWD. Nonetheless, the impact of this reversal was significant, because the initiative did not come from outside the colony as the literature argues but from local actors, who were increasingly aware that the system did not work.

The Transition from Paid Forced Labour to Paid Voluntary Labour on PWD Roads

In 1908, the announcement of the construction of an all-weather road linking Tamale with Kumasi (the headquarters of the Northern Territories and Ashanti Protectorates) marked a watershed in the transportation history of the north.Footnote 39 Approximately 230 miles in length and with an estimated cost of £130,000, it was the first large-scale project in the northern protectorate. A special department was established in 1909 and by 1915, the most complicated part of the road in Ashanti, the first sixty-one miles (Kumasi–Ejura), had been gravelled and taken over by the PWD. However, the story in the north was rather different: the District Commissioner, instead of the PWD, was in charge and work lagged well behind. Efforts had concentrated on a swamp extending six miles from the Volta River to the village of Makongo without noticeable results. In 1911, the road was in such a state that trade in Salaga declined and work had to be suspended to search for a new alignment.Footnote 40 Work resumed and a permanent gang was hired to maintain the road during the wet season, but, in 1917, rain almost destroyed all the work that had been thus far completed. It was not until 1920 that it was announced that the road should remain open through the wet season unless abnormal rains occurred.Footnote 41

There are no data concerning wages at Makongo before 1914, when recruitment of labour from all the districts of the Northern Territories began. Road workers usually received the same wage that porters earned; in the initial years of the protectorate, this was the same for all the colony: one shilling per day plus three pence for subsistence. However, by 1913, a considerable wage gap existed between the rest of the colony and the Northern Territories, where porters’ wages had been reduced to six pence when carrying loads and three pence without them.Footnote 42 By comparison, wages at Makongo in 1914 were high: nine pence plus three pence of subsistence. Yet, labourers could only be obtained by coercion.Footnote 43 Although the unhealthy condition of the swamp and the high cost of food there played a role, the main reason was the high demand for northern labour on cocoa, where the daily wage was between one shilling and one shilling, six pence per day plus free board and lodging.Footnote 44

Makongo turned out to be a frustrating experience for all involved: technically, the work did not produce the desired results for more than a decade, and the conditions for workers worsened over time. The trigger was a letter from the Acting Director of the PWD to the Colonial Secretary after the District Commissioner asked the PWD to pay the same wage as at Makongo for some works at Salaga. The Acting Director warned that, unless the labour market was controlled, costs in the north would become prohibitive for the PWD.Footnote 45 Commissioners pointed out rising living costs and the high wages paid to cocoa or road workers just across the Volta, which made it very difficult to obtain labourers. However, they neglected to mention that they were paying between three and six pence for similar works at the district level.Footnote 46 By January 1916, wages had been reduced to six pence, which was the wage for district works.Footnote 47 This wage was specific to Makongo because when the PWD started works on another swamp at Yamalaga in 1920, the wage was fixed at nine pence.Footnote 48 Still, it was low compared to what northerners obtained in the south; as a result, workers deserted and were punished for breaching their contracts.Footnote 49

When the PWD took over Makongo in 1920, it continued to pay the same wage until 1925, when chiefs protested against wages and the duration of contracts.Footnote 50 This time, the District and Provincial Commissioner rallied around the chiefs and ruled that people had worked at such wages to open up the country, but once there was traffic, the PWD had to pay market rates, and labourers had the right to work for shorter periods.Footnote 51

The sequence of these events subverts the causal direction assumed by the existing literature. Commissioners and chiefs considered that the wages for works that exceeded the interests of district populations – in particular, those that involved the PWD – had to be high enough to attract labourers. In other words, no forced labour should exist on this type of public works, a distinction that would be narrowed down to the local level in the Forced Labour Convention.

Sent to Savelugu to tell Chief that the P.W.D. are willing to employ 50 men at 9d a day […]. I met Mr Twydell I.W. to-day who told me that the Chief of Savelugu had “failed to provide the labourers asked for”. I informed Mr Twydell that no forced labour could be provided but that I had gong gong beaten in Savelugu telling the people there was work to be had for 9d a day.Footnote 52

This extract belongs to a diary dated June 1930, a year before Britain ratified the Forced Labour Convention. The rapidity with which the principle of no forced labour on PWD works was seized by district commissioners and became policy, even without legal changes, suggests a wide consensus over where to limit forced labour. At any rate, concerning public works in charge of the central government, the role of the Convention was to corroborate a policy that was already being implemented.

There are good reasons that explain why the movement away from forced labour started on PWD roads. Between 1925 and 1929, the number of southbound lorries and trailers in the Northern Territories increased from 1,352 to 7,637.Footnote 53 Damage on roads soared and some problems appeared for the first time such as corrugation. Moreover, all-weather roads had to be maintained during the rainy season, which was the planting season. There were few options: either to increase forced labour or to increase wages to attract voluntary labour. The first policy had little support among those who had to implement it: by 1929 in the Salaga District, labour north of Makongo was paid at nine pence a day, whereas at Makongo and the south of that village, the going rate was one shilling.Footnote 54

An important exogenous factor that facilitated the end of paid forced labour was that nine pence became a good wage by 1931. The world crisis of 1929 enormously affected the labour market of the Gold Coast. Cocoa prices between 1930 and 1946 were low and wages fell:Footnote 55 in the Mampong District in 1934–1935, the annual salary of a cocoa worker was only £3; in a plantation in the Eastern Province, the daily earnings were 12.3 pence in 1936–1937, 5.8 pence in 1937–1938, and 7.5 pence in 1938–1939. Cocoa no longer guaranteed higher wages than the PWD.Footnote 56 It was only after World War II that wages in cocoa increased again to two shillings or two shillings, three pence a day.Footnote 57 By then, paid voluntary labour on roads was firmly established and wages increased as well – for instance, in the Krachi District in 1948, the rate for road work was one shilling and six pence.Footnote 58 The 1929 crisis affected all sectors: the average wage fell from one shilling and six pence in 1930 to one shilling and three pence in 1931. That wage did not include food, whose daily cost in large southern villages was six pence and in Accra, nine pence.Footnote 59 Therefore, from 1931, the wage offered by the PWD in the Northern Territories was attractive, and district commissioners began to report an abundant labour supply that made compulsion unnecessary.Footnote 60

It should be remembered that until the Forced Labour Convention, compulsory labour for public purposes was considered acceptable as a part of the colonial populations’ “education”.Footnote 61 Although the Northern Section of British Togoland was administered from the Northern Territories Protectorate, it was actually a mandated territory of the League of Nations; the mandate prohibited all forms of forced labour except “for essential public works and services, and then only in return for adequate remuneration”.Footnote 62 The Forced Labour Convention banned such paid forced labour; however, as explained previously, changes preceded the Convention. Indeed, PWD roads deteriorated when the PWD ran short of funds: in 1930, the condition of the Tamale–Yendi road worsened to such an extent that the District Commissioner's proposal of taking over and managing it with PWD funds was accepted.Footnote 63

In truth, forced labour had not disappeared from PWD roads when the Convention came into effect because, according to the Roads Ordinance, people still had to maintain roads. In PWD roads, this meant weeding and cleaning, especially after rains. However, that was also changing and, by 1936, the PWD preferred that those roads carrying large traffic volumes did not traverse villages.Footnote 64 This signals a turning point in the road policy, because the existence of a local population with which to maintain roads had always been the most critical factor for allocating public investments.

The Forced Labour Convention's role in reinforcing – instead of triggering – changes was not exclusive to the Northern Territories. Okia shows that in Kenya, after 1925, the administration used what he calls “government-forced labour” only once.Footnote 65 The main question lies in the limited impact of this change, given that the central government was responsible for only a minority of roads: in 1930, the PWD maintained only 197 miles in the Northern Territories, while the political department (district commissioners) was in charge of about 300 miles of “all-weather” roads and 1,600 miles of dry-weather roads.Footnote 66 Therefore, the decisive struggle against forced labour was on political roads.

Indirect Rule, Taxation, and Unpaid Forced Labour

The main characteristic of the road system of the Northern Territories was its extensive network of roads within the purview of the political department. The political road mileage of the Eastern Dagomba District alone was similar to that of the whole Ashanti Protectorate, although their respective areas were 5,503 and 24,378 square miles. This imbalance was a consequence of the dearth of PWD roads in the north: only 197 out of 1,868 miles maintained by the PWD were located in the Northern Territories, even though this protectorate constituted more than one third of the colony.Footnote 67 Another characteristic was the non-existence of roads constructed and maintained by traditional authorities using exclusively their own funds. The reason was that only traditional authorities in possession of mining concessions or receiving tribute from cocoa farmers could afford such investments.Footnote 68

Kunkel argues that the introduction of indirect rule in the Northern Territories was a strategy to circumvent the Forced Labour Convention. By handing over political roads to chiefs – about 1,900 miles – the colonial administration exploited a loophole in the Convention that made it possible for chiefs to use forced labour on public works that were of local interest during a transitional period of five years. Not all miles could be classified as such, so direct taxation was introduced to allow chiefs to pay for labour on trunk roads. However, the administration did not control whether chiefs paid labourers, so forced labour also continued on trunk roads. According to Kunkel, the Convention was negative for northern populations because, in addition to providing forced labour, they also started paying taxes to maintain roads.Footnote 69

Kunkel's argument assumes a consensus among colonial officials that did not exist: as will be seen, forced labour was a contentious issue that generated significant tensions. Furthermore, those officials who supported indirect rule and direct taxation envisaged them as steps towards ending forced labour rather than the other way round. Finally, debates on forced labour did not start in 1930 due to the imminent ratification of the Convention by Britain, but, in fact, began earlier and in relation to the introduction of indirect rule. Indeed, the substitution of taxes in kind with money was one of the central pillars of this new policy.

In 1927, in response to a letter from the Provincial Commissioner about the existing system of in-kind taxation (mainly, labour on roads and tribute to chiefs), St. John Eyre-Smith, the District Commissioner of Lawra-Tumu, recalled the reports that he had already sent about the “gross injustices that are inflicted as the result of our present system”. He proposed introducing a tax per head of the male population, paying all road labourers at three pence per day and handing over all public works to the PWD.Footnote 70 In 1928, the political staff of the Northern Province sent a collective document in which they defended the abolition of all unpaid labour, the exception being “cleaning grass, ditches and repairing small washouts of roads”, but only until the revenue was sufficient to pay “ALL labour”.Footnote 71 The following year, perhaps because of the lack of success, their proposal was somewhat watered down:

The Conference thinks that 6/- per head would be a fair tax, to replace twelve of the twenty-four days labour (at 6d. per diem) at present due on the roads and that a man should be given the option of giving twelve days work for his tax if he has not the cash available. The other twelve days should be abandones [sic], except that the Chief could call on the people for not more than seven days at the end of the rains to clean the roads, &c. All other unpaid labour to be abolished.Footnote 72

The main stumbling block was Chief Commissioner A. H. C. Walker-Leigh, who led the opposition to indirect rule and taxation. He mistrusted the chiefs and warned about the potential negative effects that paid labour might have on the seasonal labour migration to cocoa-producing areas, because “there would be no necessity for them to go down as they would be able to get work up here and plenty of it”.Footnote 73 It was not until he retired in 1930 that the introduction of indirect rule could really get underway.Footnote 74

More importantly, during the years preceding the Forced Labour Convention, movements against forced labour were not limited to sending proposals, and some district commissioners were already acting in this direction:

The mileage of roads says Eyre Smith, the number of well kept Rest [sic] houses are all testimonies to the administrative abilities of the Chiefs, what about the number of Police necessary to back up the Chiefs efforts to get labour in. Since Guthrie Hall ceased to carry on Brace Hall's policy of using Police on roads the deterioration of the road has been marked.Footnote 75

What is most striking about the period between the mid-1920s and the mid-1930s is that no coherent policy existed, and the actual degree of unpaid forced labour depended to a large extent on district commissioners, some of whom used the money allocated to chiefs for road maintenance to hire labour: in 1926–1927, for the Salaga–Krachi road, £108 out of £150 was expended on unskilled labour (equivalent to 2,884 daily wages).Footnote 76 The District Commissioner of Krachi recorded in the District Record Book and his handing-over report that, as Krachi was in mandated territory, all labour even for essential Public Works “must be paid for”.Footnote 77 Nonetheless, the Provincial Commissioner instructed the new acting commissioner that unpaid labour “must of the necessity be used for roads repairs” as there was not enough money. He added that Krachi was under the laws of the Northern Territories, so people were required to pay a labour tax of twenty-four days.Footnote 78 In 1931, it was reported that, in Krachi District, those living on main roads had provided communal labour for cleaning; however, in 1932 it was reported that all these roads were maintained by paid gangs.Footnote 79

The situation in this district stands in marked contrast with what was happening in the Konkomba area of the Dagomba District, where, in 1930, Assistant District Commissioner H. A. Blair appointed special elders to organize road labour; penalties entailed a doubled amount of work.Footnote 80 Road work was considered an “educative measure”, and people worked up to sixty days yearly.Footnote 81 The ruthless methods used in this area had already drawn the attention of the Governor in 1928 when the Assistant District Commissioner burned houses and took cattle as fines without trial. Although Chief Commissioner Walker-Leigh argued that these methods were the only way of controlling recalcitrant populations, the Governor ruled against them in future. However, in 1934, Blair burned a village without realizing that a woman was inside a house. Her death prompted an inquiry from the Colonial Office into the extent of these practices in African colonies. The Colonial Office warned that those who ordered the burning of houses would be liable for all legal consequences.Footnote 82 In the Konkomba area, road labour started being paid at three pence a day in 1935, and, in 1937, when a chief asked the District Commissioner to support him in the context of forced road work, the latter explained to him that the practice was obsolete and that the policy now was to pay for labour.Footnote 83

Although these data indicate that shifts in labour relations were occurring in PWD and political roads at the same time, it is important to determine their extent and what the handing over of political roads to native authorities meant for them. The latter was part of the implementation of indirect rule that started in 1932. Direct taxation was also part of it, but it did not start until 1936.

At first sight, the most obvious impact of the new policy was a spectacular decrease in the number of miles maintained: between 1930 and 1938, whereas PWD roads increased slightly from 197 to 220 miles, political roads were drastically reduced from 1,900 to 630 miles.Footnote 84 I focus first on these 630 miles and on the argument that direct taxation was introduced to pay for the labour on them; later, I shall explore what happened with the rest.

An important source of information is the budgets and estimates that native authorities had to prepare under the supervision of district commissioners. These budgets show that political roads (or “native roads”, to use a more period-appropriate expression), were not financed by the poll tax but rather by grants from the central government, which increased substantially in the mid-1930s: for example, in the second quarter of 1923, the whole Southern Province received £375, whereas in 1937–1938 expenditure for the Krachi District alone was £1,730 and the grant for the Eastern Dagomba District was £2,024 (in 1927–1928 expenditure for the latter district was only £342).Footnote 85 Because this increase coincided with a decrease in the mileage maintained, there was much more money available per mile. That the goal of the latter was, above all, to pay for unskilled labour is suggested not only by the frequent journeys to pay labourers that district commissioners mention in their diaries, but also by the conditions that the Colonial Secretary put in 1941 to some southern native authorities that petitioned to manage these grants. The model was the Northern Territories and the conditions were that district commissioners had to verify that roads were properly maintained, that the money was not to be diverted to other uses, and that labour was regularly paid.Footnote 86

Native authorities of the Northern Territories remained always dependent on central government for maintaining and improving roads. Although the twenty-four days of the labour tax initially served as a reference to decide the rate of the direct tax, the latter was finally established at a much lower rate. A wage of six pence per day for twenty-four days would have established the tax at twelve shillings per adult male; however, in Gonja the tax was fixed at two shillings and six pence, in Krachi from two shillings and six pence to one shilling and six pence, and in Dagomba between two shillings and one shilling.Footnote 87 The budgets of the native authorities show that the principal source for financing roads came from the grants-in-aid of the central government: in 1937–1938, in Krachi District, the total tax collected was £607, while the grant-in-aid for roads was £1,728.Footnote 88 In this district, in 1949–1950, expenses on roads were £5,283, and the government granted £5,516.Footnote 89 In 1938, the Dagomba Native Authority voted to spend £788 from their own resources while the grant-in-aid amounted to £2,112, and in 1946–1947 the government reimbursed £3,255 out of £4,668 expended.Footnote 90 Internally generated revenue (which included sources other than the poll tax) financed, at most, one third of the native roads (PWD roads had their own funds).

Despite the value of the poll tax being much lower than the shadow price of the labour tax, it was published as its substitute and, initially, it was possible to choose between them. This was especially true for those communities regarded as poor and that might have difficulty paying the tax. Nobody chose the labour tax, but the result of this initiative was that even marginal communities were made to understand that the poll and labour taxes were incompatible.Footnote 91

A comment wrote by the District Commissioner of Dagomba, C.E.E. Cockey, in 1936, illuminates the mood at the time of the introduction of the tax:

Have been reading the Ashanti Report […] Their Political road mileage is about the same as Dagomba but I am interested in what is written […] “communal labour has been abolished and maintenance is now undertaken by paid gangs […] The new system is an improvement and it has been found that roads can be kept in better average condition by skilled gangs than they were when they [were] cleaned and maintained by ill directed labour”. I realized that (I was not the only one) years ago and acted on it but all I got was an official raspberry and a report that I lacked initiative.Footnote 92

In the margins of this diary, probably written by the Provincial Commissioner, is the following sentence: “You have the small satisfaction of knowing that you were correct.” The extract and the comment show that, at the end of the transitional period of the Forced Labour Convention, the consensus was that compulsory labour for roads did not work.

Legislation was adjusted to comply with the Convention: road work outside the limits of a village had to be remunerated at the same rates as voluntary labour; unpaid labour was restricted to the maintenance of roads and paths running through villages, or to the farms of the village inhabitants or the nearest water supplies (roads in towns were maintained by the PWD or the native authorities); and complaints had to be reported directly to the Governor by district commissioners.Footnote 93 The last provision was perhaps a legacy of the confrontation between an increasing number of provincial and district commissioners and the Chief Commissioner until 1930.

This change in legislation, the end of the Convention's five-year transitional period, and a recovery in government revenue in 1936 accelerated the transition to paid voluntary labour on the roads within the purview of native authorities.Footnote 94 Forced labour remained a possibility, but it required the Governor's approval. For instance, when, in 1940, a Dagomba chief was killed in the Konkomba area, the Chief Commissioner obtained approval to punish all Konkomba villages, regardless of whether they had been involved, by constructing embankments to transform a road into all-weather to access the area during rains. The irony was that the embankments were constructed too low and the area continued to be inaccessible, providing a further example of the wastage of labour power that had characterized the forced labour system.Footnote 95

Did forced labour continue on the 1,270 political miles that were not handed down to native authorities? It is doubtful that the political department regularly maintained all the miles listed in 1930. In any case, the PWD continued to absorb part of them, its network totalling 436 miles by 1950.Footnote 96 Native roads also expanded in parallel, especially after World War II (some examples are provided in the next section); thus, part of this mileage was absorbed by either the PWD or the native authorities. However, because that was a decades-long process, the most immediate consequence of the Convention was the abandonment of many political roads. It particularly affected feeder roads connecting villages to trunk roads, as they were not exempted from the ban on forced labour and the majority of them were not absorbed by the PWD or the native authorities. Moreover, the context for hidden compulsory labour was not favourable since people were paying the tax, and district commissioners had few incentives to support abusive chiefs. Indeed, the willingness of local populations to provide voluntary labour was a major determinant of the destiny of these roads. That, in turn, depended on their interest in motor transport. When no such interest existed, roads simply reverted to bush tracks that required little maintenance.Footnote 97 But when it did, motor transport created an unprecedented demand for labour that, in the long run, set in motion decisive transformations in labour relations, which the next section analyses.

There was an area where forced labour continued without noticeable change during the whole colonial period: that of tribute, or the payments that populations made to chiefs. Tribute was usually paid in kind (farm produce, livestock, etc.), but the obligation to work on chiefs’ farms was very common. The British administration never regulated tribute except the tribute paid by migrant cocoa farmers, even if flagrant abuses cropped up from time to time: the above-mentioned murder of the Dagomba chief occurred because that chief took the best cattle from a village. In the Konkomba area, abuses in tribute are well documented and were part of the everyday experience of populations.Footnote 98 They were ended by local initiative in the 1960s, when village after village decided not to pay anymore. Villages feared a violent retaliation to their defiance and were prepared to defend themselves, but the days, weeks, months, and years went by and “until today nobody has come”.Footnote 99

People's Roads and Unpaid Voluntary Labour

Northern populations constructed and maintained roads on their own initiative before and after colonization, but by decreasing transport costs and opening up distant food markets, the lorry changed the significance of roads for many populations. Nevertheless, lorries greatly complicated road building: it was not enough to clear a path; roads had to be much wider, dotted with culverts and preferably gravelled. In addition, rocks had to be blasted and bridges able to withstand overloaded lorries. Rural populations had a good knowledge of the terrain and mastered some of the skills, but they rarely could afford the high costs of bringing materials to the north and were unable to attract masons or carpenters. For that, they turned to district commissioners and native authorities and offered their labour in exchange.

I focus on the triangle formed by Krachi, Salaga, and Kpandai, where northern migrants started arriving in the early twentieth century and, beginning in the 1920s, food began to be exported by lorry to southern urban markets. The aim of concentrating on a specific area is to provide a measure of the significance of people's roads and their impact in transforming labour relations. However, such roads were not unique to this area: I documented similar processes in other areas of northern Ghana and Ashanti and the roads that Wiemers interprets as being constructed by chiefs using forced labour can be reinterpreted in light of farmers’ interest in motor transportation since these initiatives coincided with the spread of lorries into rural areas.

From the late nineteenth century until the beginning of World War I, the area under study was split between the Germans and the British. Krachi and Kpandai were occupied by the British in 1914 and later included in the northern section of the British mandate for Togoland, which was administered from the Northern Territories. Kpandai was by then a small village, but Krachi (Kete) was a prosperous commercial town where all produce coming from or going to the coast by canoes through the Volta River had to be unloaded due to the existence of rapids.

The initial priority of the British administration was to link Krachi with Salaga in order to connect the area with the Tamale–Kumasi all-weather road that was by then under construction. However, the Dakar River proved to be a formidable barrier, and some money began to be devoted to an alternative route: the Krachi–Chindere–Kpandai, constructed during the German period with forced labour brought from afar due to the scarcity of the local population.Footnote 100 This route connected Krachi with Yendi, another important commercial centre that became British after World War I. It was on this route that most efforts were concentrated, Krachi being finally connected to Salaga through Chindere.Footnote 101

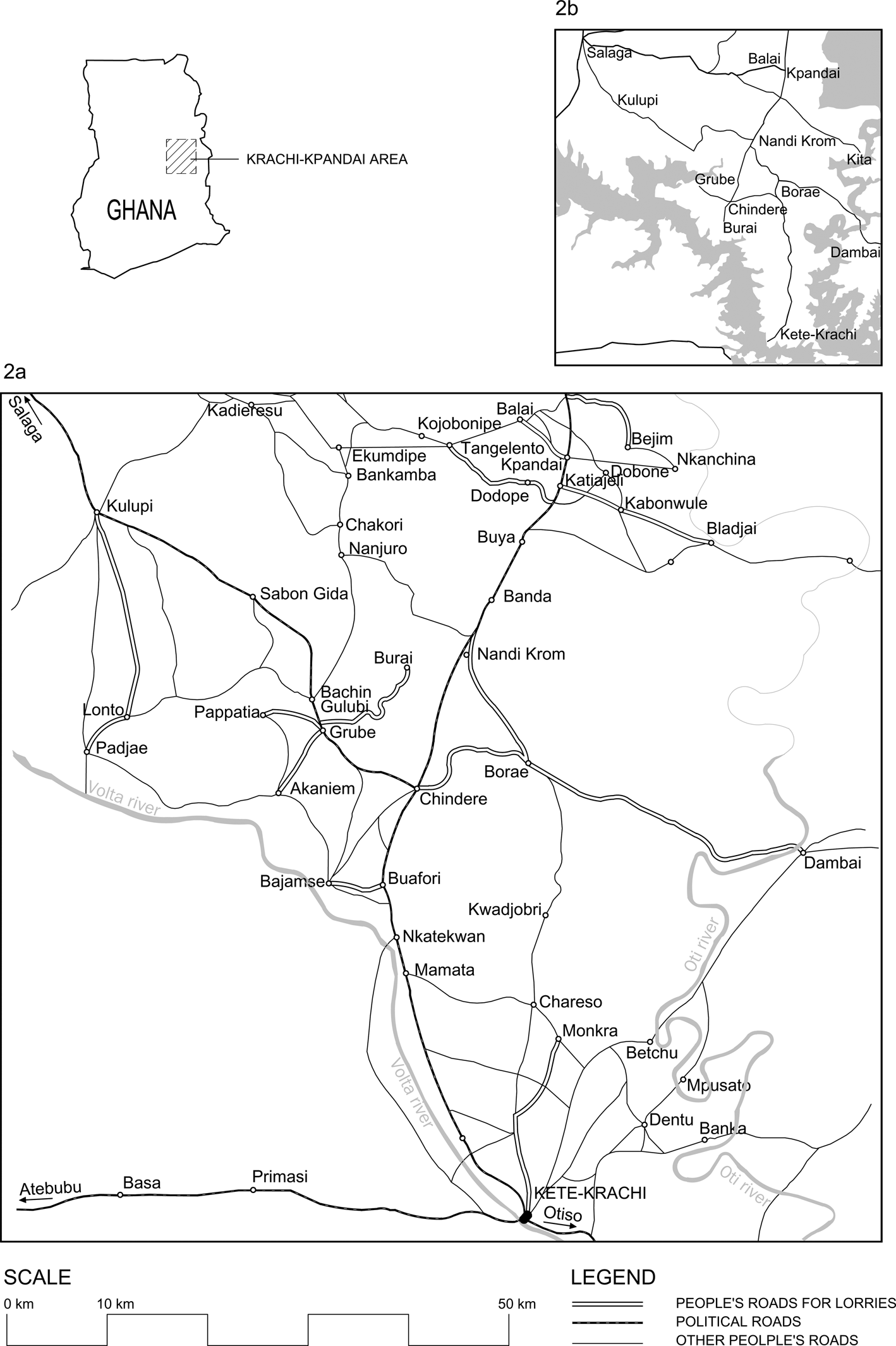

Until the 1950s, funds were devoted to the Krachi–Kpandai and Krachi–Salaga roads and the connections between Krachi and Atebubu and Otiso (see Figure 2a). Because the population was sparse, labour for improvements and some maintenance works soon began to be paid.Footnote 102 It was in this area that the District Commissioner left instructions in 1929 for his substitute that, because it was a mandate, labour on public works had to be paid.Footnote 103 The strategy to avoid forced labour was to concentrate only on the main roads, to use the money allocated under the Roads Ordinance to pay labourers instead of chiefs, and to apply for extra funds whenever it was possible. The year 1937 was a sort of threshold in this area: indirect rule, direct taxation, and the new legislation converged with a sharp increase in both funding (in 1937–1938, £950 out of £1,700 was spent on road labour – an amount never before seen) and traffic (the number of lorries on the main road increased from 873 to 3,028).Footnote 104

Figure 2. a. Present-day map; b. Colonial-period map.

Petitions for aid from villages started with lorry traffic in the early 1920s. For instance, the chief of Nawuri was granted tools and one shilling and six pence a day for fifteen days to repair the road, while the inhabitants of Bajamse asked the District Commissioner to mark out the best route to link their village with the trunk road in 1928.Footnote 105 However, from 1937, increasing funds and the recently created native treasuries allowed for the funding of roads other than the main ones: after Tangelento and Dodope were linked to Katiajeli and Balai to Kpandai on the initiative of villagers, the District Commissioner induced the native authority to grant each village £5 for the road and £6 for wells.Footnote 106

The increase in lorry traffic in 1937 prompted a burst of activity, and, by 1945, Bladjai, Bejim, Pappatia, Monkra, Kwaku, Burai, Akaniem, and Grubi Banda had been connected to the main roads, and petitions for assistance or bridges had not ceased (see Figure 2a).Footnote 107 The District Commissioner murmured that these roads constituted a “constant source of bother”, because wherever he went, people reminded him that a previous district commissioner or the native authority had promised to build bridges provided that they cleared and levelled a line.Footnote 108 People's roads continued to crop up: Lanto cleared and uprooted all trees within fourteen miles, and the Assistant District Commissioner of Salaga surveyed the line for bridges and culverts but promised only tools to the people of Pajai.Footnote 109

District commissioners called these roads “yam roads” because their primary purpose was to export yams to southern towns: in April 1945, when a shortage of fuel stopped exports, the road to Bladjai, which had been thus far carefully maintained became “little more than a bush track”.Footnote 110 Not only did traders and lorry drivers come to the area to buy produce but farmers also paid the lorry freight and travelled to Accra markets, where they obtained higher prices.Footnote 111 These roads were not a product of forced labour extracted by chiefs but rather one of voluntary labour by farmers interested in marketing their produce and improving their living standards. Indeed, the majority of villages mentioned above were founded by migrants and had no real chiefs. For instance, the District Commissioner was surprised that the people of Bajamse had collected stones for a bridge, because the chief and elders had little authority there.Footnote 112 The oral testimonies that I gathered, which belong mainly to the late colonial and independence periods, talk about teaming up among villagers or even villages. However, although agreements could be easily reached because most of the population were farmers and shared interests, some promoters failed to convince other inhabitants and ended up constructing a road alone: the only two migrants who owned lorries in Borae constructed the road to Chindere by hiring workers and using their own lorries, money, and labour without the collaboration of the rest of the village.Footnote 113

The ability of people to attract government resources varied. Those involved in the Lanto road succeeded: in 1952, £100 was spent on bridges;Footnote 114 in 1956–1957, the road was widened by villagers, ditched by a tractor brought by the District Commissioner, £475 was paid for gravelling and, most importantly, £600 (£40 per mile) was included as annual recurrent costs for its upkeep.Footnote 115 Due to the territorial reorganization that indirect rule involved, Kpandai was finally included in Gonja instead of Krachi. To improve links with Salaga, the district capital, the new native authority started devoting money to the maintenance of the Kpandai–Bladjai and Balai–Kpandai roads, both people's roads.Footnote 116 The Balai–Kpandai road became part of the Salaga–Kpandai road, whose importance and funding changed completely in 1956 when it was realized that the Volta Dam would flood the Salaga–Chindere road and interrupt all communication between Salaga and Krachi.Footnote 117

The foregoing cases provide examples of roads that were taken over by the state or native authorities relatively quickly. That was not typical: the majority of people's roads received only ad hoc funds. For instance, when money was voted for the British Togoland plebiscite, the District Commissioner used £1,200 to pay 500 persons to improve the roads of their villages, and a new road from Nanjuro to Chakori was constructed.Footnote 118 But local populations continued to take responsibility for the roads’ upkeep.

The majority of the money came from development funds. People's roads were attractive to the mass education or community development projects that started in 1950 because communities were looking for investments, especially in permanent structures. However, when the benefits were unclear to those who had to work – for example, to connect a leper settlement near Nkanchina with Kpandai – projects tended to progress slowly or had to be abandoned.Footnote 119 The unpaid labour that constructed and maintained many roads was not a creation of development discourse but was rather both a cause and consequence of the spread of lorries into rural areas. To interpret such labour as “forced” obscures who led the initiative and what populations were working for.Footnote 120 It should be borne in mind that the Convention banned forced labour on public works but did not establish a minimum that had to be maintained by paid voluntary labour. Public works could be abandoned – indeed, as seen above, the majority of roads were. This was especially true in rural areas that generated little revenue: rather than a state contriving plans to expand its presence at little or no cost through the construction of infrastructure, it was the population who, individually or collectively, worked to pull the state into their areas.Footnote 121 Initially, people's aims were to solve a particular problem – a bridge or a rocky area – but as traffic increased and the burden of maintenance grew exponentially, handing over people's roads to the state became a major objective. The idea that the state had to be responsible for roads was the outcome of a process that required a profound change not only in the perceptions of the state or roads by all those involved in them, but also in how rural populations perceived themselves. Again, that transfer of responsibility was a local process, negotiated on the ground, road by road. The inclusion of a road under the heading of “recurrent costs” signalled that a new threshold had been reached: labour for that road's maintenance would be regularly paid in future.

Despite uncertainties about its dates, the history of the Nandi Krom–Dambai road sheds light on the protracted negotiations that handing over of a road to the government entailed.Footnote 122 Around 1950, a group of migrants settled in an uninhabited area south of Banda. They started exporting food crops through the Kpandai–Krachi road, but when the connection between Dambai and Accra was improved in the mid-1950s, they widened a path to link their village, Nandi Krom, with Dambai. The area prospered, and one of the migrants, Nandi Banda, became very rich. He was strategic in using his resources – he donated food to the Dawhenya Irrigation Project and the Ho and Hohoe hospitals – and mobilized local labour to attract public investments, using his own lorries to transport local people where needed for work and also feeding them. The Volta Dam was a propitious event that led to government involvement with this road, albeit not in a definite way. The government blasted rocks, bridged streams, and improved the route in exchange for free accommodation and food for workers. Elder people say that the road was satisfactorily maintained even during the crises of the 1970s and 1980s but deteriorated after Nandi Banda's death in the mid-1990s, because cooperation among the inhabitants themselves faltered. In 2014, the asphalt was in a ruinous state, full of potholes of all sizes. In 2016, a year of general elections, works to broaden and resurface the road started. However, they progressed so slowly that during the general election campaign, graffiti reading “no roads, no votes” began to appear at different parts of the route. The graffiti did not seem to have an impact until the week of the elections, when rollers and bulldozers started working even at night. Although this last-minute rush was to no avail for the ruling party, which lost the elections, it shows that another profound transformation had occurred after the end of Nandi Banda's period: people no longer used their labour, but rather their votes, to attract government resources.Footnote 123

Because independent governments experienced sharp declines in revenue that obligated them to cut expenses, a road's inclusion among works of a recurrent nature did not signal the last stage of its handing over to the state. Indeed, attempts to revert to the stage in which people could be asked to volunteer labour were frequent, as were people's resistances to them. When the administrative officer of the independent government of Gambaga started an operation that he named “Walewale–Gambaga repairs” and, using the language of self-help, appealed to chiefs and elders for unpaid voluntary labour, he received similar answers everywhere: “Negative. Blunt refusal. They are ‘not labourers’. The road is for the PWD.” In the face of this refusal, he ended up requesting aid from the Regional Organisation of Labourers.Footnote 124 This example, as well as what I witnessed with the Nandi Krom–Dambai road, indicates that the final stage of the confusing give-and-take involved in the handing over of a road did not occur when the state announced the takeover of a road but rather when the population considered that the road was no longer theirs and that they were no longer responsible for its condition.

The protracted and local nature of these processes may obscure the far-reaching changes that they entailed. In the area of Krachi–Salaga–Kpandai, the mileage of people's roads that I have documented was greater than that of PWD and native roads combined, and I have not even documented all people's roads. Furthermore, the current public road network is constituted from former people's roads (see Figure 2b): The Volta Dam, Nkrumah's main development project, started filling in 1962; the Volta and Dakar Rivers swelled and engulfed Makongo and large stretches of the Salaga–Krachi road, forcing the connecting of Salaga and Krachi via Kpandai through the road initiated by the people of Balai in 1937; at the same time, the old German road of Krachi–Chindere–Kpandai was overflooded south of Buafori; Chindere, formerly a node, became a terminus whose connection with the south began to depend on the road constructed by the two lorry owners from Borae, without the help of other villagers; Krachi lost its central place in favour of Dambai, and the hunting path widened by the migrants settled in Nandi Krom became the principal road of the area. Looking at a present-day map and tracing the history of its roads shows that for the inhabitants of this area, the most significant shift in labour relations did not occur when forced labour became voluntary, but rather when unpaid voluntary labour became paid. As stated above, these processes were not specific to this area or even the protectorate: Governor Hugh Clifford acknowledged that three quarters of the motor roads build during World War I were constructed by people.Footnote 125 Moreover, the roads within the purview of the state expanded, in truth, after colonization, locating this shift in the post-independence period: the mileage maintained by the PWD had increased only from 1,868 miles in 1930 to 4,293 miles by the time of Independence, whereas a total of 21,636 miles were “routinely maintained” by the Ghana Highway Authority and the Departments of Feeder and Urban Roads by 2019.Footnote 126

CONCLUSIONS

This article has shifted the debate on forced labour in African colonies from a focus on external pressures and how colonial governments resisted them to a focus on how local conditions contributed to the end of forced labour. This shift reveals a chronology wherein the movement towards paid voluntary labour begins earlier than previously assumed and in which lorries play a central part. Lorries’ centrality underpins the importance of local actors in shaping changes because farmers, drivers, traders, and consumers were those who kept lorries on the road. Contrary to the idea that indirect rule was a strategy to continue with forced labour, indirect rule accelerated the end of unpaid forced labour. However, I have also highlighted that, for many rural populations, the most significant transformation occurred when their unpaid voluntary labour became paid. The contribution of voluntary labour to state revenue and the conditions that facilitated its transition to paid labour warrant further research.

The findings of this article call into question some dominant ideas in the current literature. As I have already pointed out, several of the processes identified in these pages are not specific to the Northern Territories. However, further research on the role of local conditions in other contexts will improve our understanding of how public works impacted labour relations in the colonial period and beyond.