1. Introduction

A new construction is emerging in Norwegian. This construction – here referred to as the ei litta construction – involves a morphological marker of feminine gender, the indefinite article ei, as well as a lexical expression of diminutive, litta or lita ‘small’, where the inflectional ending is feminine. The unmarked way of using this feminine-agreeing adjective is with a noun of the feminine gender, as in (1):

(1)

In these constructions, the meaning is – predictably – that of diminution. However, the novelty of the construction lies in its ability to occur with nouns that are grammatically masculine or neuter, as seen in (2), and sometimes also biologically masculine, as in (3):

(2)

(3)

Lita vs. litta represents a difference in the length of the first vowel: the former long, the latter, most common in the innovative use discussed here, short. The use in (2) and (3) creates a meaning beyond diminution, among them ‘affection’. Recently, this construction has gained attention because of its use in the massively popular TV series SKAM, which ran on national television from the years 2015–2017, with notable examples being ei litta tur ‘a small trip’ and ei litta vits ‘a small joke’. Opsahl (Reference Opsahl, Karlsen, Rødningen and Tangen2017) provides a description of the innovative use of ei litta with grammatically male nouns in Norwegian. She focuses on the uses of this construction in social media and suggests it may be a ‘sub-norm’, used in certain speech acts as a form of ‘softening’ of acts of self-exposure on social media, such as posting selfies and other personal content. By adding ei litta, as in ei litta selfie, Opsahl argues, the stakes are lower, and not receiving expected feedback (in the form of many ‘likes’) would be easier to handle when the exposure is presented as small, or not important, in the first place. Opsahl argues that this use is related to an otherwise well-established tendency of subjectivization, often observed in diachronic change, or ‘hedging’; namely, the softening of the linguistic content through pragmatic markers.

Using corpus data from a 700-million-word corpus of non-edited written language, Norwegian Web as Corpus, abbreviated NoWaC (Guevara Reference Guevara2010), and through eliciting intuitions of native speakers of Norwegian through a questionnaire, we look at which nouns occur with the construction, and assess its semantic and pragmatic effects. We further investigate the construction in the context of evaluative morphology and diminutives, using Jurafsky’s radial category model as a backdrop (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996). Through a survey of native Norwegian speakers assessing minimal pairs, we compare their assessments of the semantic and pragmatic effects of the construction with the categories presented by Jurafsky, finding that a salient pragmatic effect of the construction is hedging. We also address the diachrony and productivity of the construction using Twitter data.

We finally situate the construction typologically and cross-linguistically within the frame of evaluative morphology. Typologically, we observe that the Norwegian construction is particular: it involves both a lexical marker of diminutive (litta), two morphological markers of femininity (ei and the feminine-agreeing form litta), and that it is likely the combination of this with masculine and neuter nouns that triggers the specific meaning.

The paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we provide an overview of diminutives and evaluative morphology. In Section 3, we outline the gender system of Norwegian, and the variation within it. We also describe some recent changes to the traditional three-gender system. Section 4 presents the goals and research questions of the present study, and describes the methodology used. In Section 5 we describe the results of the corpus study and the survey. Section 6 contains a discussion of the findings, and in Section 7 we present a brief conclusion.

2. Diminutives and evaluative morphology

The ei litta construction is an evaluative expression, involving both the explicit expression of diminution through litta, and the morphological expression of feminine gender through ei. In this paper, we are concerned primarily with the way in which Norwegian nouns come to express diminutive and appreciative meaning through a combination of gender marking and a lexical diminutive.

Evaluative morphology refers to the ways in which languages morphologically express meanings such as augmentatives (bigger), diminutives (smaller), appreciatives (better), and depreciatives (worse). The term appears to originate in a study by Scalise (Reference Scalise1986), on what he in Italian labeled affissi valuativi – evaluative affixes. Departing from Romance, and specifically Italian, known for its productive suffixal use of evaluative expressions, Scalise proposed that they belong to what he calls a ‘third morphology’; not derivational affixes, not inflectional affixes, but precisely evaluative affixes. Following Scalise’s account, evaluative morphology has been studied from a number of perspectives, including cross-linguistic, typological, semantic, and formal points of view.

2.1 Jurafsky’s model of the diminutive

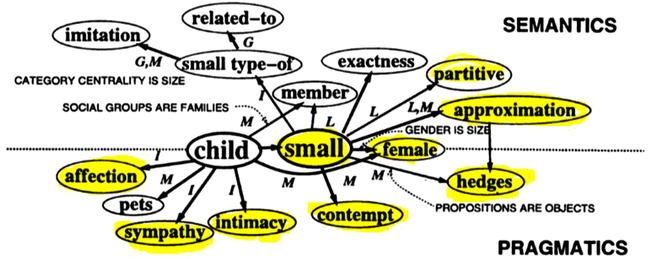

For the purpose of the present article, we will use Jurafsky’s (Reference Jurafsky1996) radial model of the synchronic and diachronic aspects of the senses of the diminutive. Jurafsky’s investigation into the semantics of the diminutive category was an early analysis of both synchronic and diachronic aspects of the category. Departing from a sample of 60 languages, Jurafsky found – perhaps not surprisingly – that the meanings of the diminutive likely originate in words semantically or pragmatically linked to children. The challenge in the semantic description of the category is its apparent contradictory meanings, in that diminutives may both express meanings of affection and contempt. Given this diversity of the meanings of the diminutive (as we shall see is indeed the case for the Norwegian ei litta construction), Jurafsky’s model was an attempt at avoiding abstract definitions of the category. Instead, he proposes a structural polysemy model, in which the different meanings are related and overlapping. The central meanings of the category are ‘child’ and ‘small’, with related meanings extending from these meanings. Figure 1 shows the categories in Jurafsky’s model.

Figure 1. Proposed universal structure for the semantics of the diminutive (from Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996:542).

Jurafsky’s categorization of the meanings of diminutives is split into two main categories (represented by the dotted line in the figure): meanings that are mostly semantic in nature, and meanings that are mostly pragmatic in nature. This split between the most central meanings of the diminutive, the semantic extensions and the pragmatic extensions, are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of Jurafsky’s categories (adapted from Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996)

The meaning categories on the pragmatic side of the figure concern speaker attitude towards an entity/situation, while the meaning categories on the semantic side are related more directly to the lexical semantics of the diminutively marked noun.

2.2 Diminutives and evaluative expressions

Diminutive is a universal or near-universal category, and refers to ‘any morphological device which means at least “small”’, following Jurafsky’s (Reference Jurafsky1996:534) definition. Diminutives may be expressed through various means; higher tone, affixes, lexical constructions, etc. (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996).

Diminution is usually expressed lexically in Norwegian, by means of adjectives such as litta. However, and importantly, in languages that have a morphological diminutive marker, this marker typically expresses meanings beyond simply diminution. Diminutives are central conveyors of several evaluative meanings, and diminutives represent, typologically speaking, the most frequent expression of evaluative morphology (Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2014). Very often, the marker for diminutive expresses that something is viewed positively. In Italian, for instance, adding diminutive morphology is a means of expressing qualitative evaluative meanings, e.g. bad or good. The diminutive may express endearment as well as diminution, as in the following examples (from Stump Reference Stump1993:1, Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996:534, 546):

(4)

(5)

In addition, in Mexican Spanish, for example, the diminutive is used as an intensifier, and changes the meaning of the adverb ahora ‘now’:

(6)

(7)

In other varieties of Spanish, however, such as Cuban, the diminutive has a different meaning, namely an attenuating force, e.g.:

(8)

2.3 Gender and evaluative morphology

Gender is a type of nominal classification strategy, most often defined as being ‘reflected in the behavior of associated words’ (Hockett Reference Hockett1958:231). However, gender also plays a role in evaluative morphology. Gender shift may be employed as a means to express evaluative meaning, and is found in e.g. African languages (see especially Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2014). In languages with sex-based gender systems, this shift may involve a change from masculine to feminine to express diminutive, and the opposite to express augmentation.

In certain languages, then, we can observe the following meaning shift caused by shifting gender:

masculine inanimate → feminine = diminutive

feminine inanimate → masculine = augmentative

The first shift can be exemplified with Tachawit (Berber) (quoted here exactly from Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2016:58, adapted from Penchoen Reference Penchoen1973:12).

(9)

(10)

In this variety, the second type of shift can also be observed:

(11)

(12)

The meaning shift in these cases illustrates the intertwined relationship between gender and size – feminine is related to small size, masculine is related to big size. Di Garbo (Reference Di Garbo2014:7) labels languages in which such shifts may occur as languages having manipulable gender assignment (as opposed to languages with rigid gender assignment). The process by which the shift occurs, she labels gender shift. According to Di Garbo, these types of shift may point to gender assignment as being less a fixed, inherent property of the noun, and less rigidly specified in the lexicon. Her study of evaluative morphology in African languages points to manipulable gender assignment as being frequent enough to ‘start considering a revision of our current understanding of gender assignment rules, their implications for the typology of gender systems, and, on a larger scale, their interaction with word-formation processes’ (Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2014:206).

While it is cross-linguistically uncommon to express evaluation through the combination of a diminutive marker and feminine morphology, it should be noted that in Bantu languages, which do not encode biological gender within the noun class system, gender and diminutive do interact in ways that are relevant to the question of evaluation. The diminutive suffix derived from the word ‘child’ can be used as a marker of female reference in very specific contexts (Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2014:170).

3. Gender and diminutives in Norwegian

3.1 Grammatical gender in Norwegian

Norwegian is a North Germanic language, most closely related to Danish and Swedish. There are two written standards, Bokmål and Nynorsk. Nouns have one of three grammatical genders in most spoken varieties of Norwegian: feminine, masculine, and neuter, as well as in the Nynorsk written standard. The Bokmål written standard also allows for a two-gender system (common and neuter gender), which is also seen in some dialects, which will be discussed in more detail below.

There are no overt morphological markers on the noun itself to indicate which grammatical gender a noun has, although there are some tendencies in gender assignment, which will be discussed below. However, there are inflectional suffixes for the definite singular form, which vary according to the grammatical gender of the noun. The gender of each noun is fixed and cannot be changed through inflection.

As noted above, a standard view of grammatical gender in the literature is found in Hockett (Reference Hockett1958:231), who proposes that ‘[g]enders are classes of nouns reflected in the behavior of associated words’. In other words, grammatical gender is seen as being expressed through agreement between the noun and words such as determiners, adjectives, and anaphoric pronouns. We will in the following present the definite singular suffixes along with the elements that agree with nouns with regards to gender, mainly to give a full account of the variations in Norwegian noun phrases conditioned by gender.

There are several indicators of grammatical gender in Norwegian: the indefinite article, the definite suffix, determiners (demonstratives and possessives), adjectives and anaphoric pronouns. The definite article, a suffix originating from a demonstrative, does not fit Hockett’s definition, as explained above. The other elements fit Hockett’s definition, since they are words that agree in gender with the noun they modify.

The paradigms in (13)–(15) demonstrate the gender agreement evident in the indefinite article and the definite article (in Bokmål).

(13)

(14)

(15)

Demonstratives also agree with the gender of the noun they modify, although there is syncretism between the feminine and the masculine gender, as seen in (16):Footnote 2

(16)

Adjectives also agree with the gender of the noun they modify, as seen in (17)–(19).

(17)

(18)

(19)

Liten ‘small’ is the only adjective that has different forms for all three genders; almost all other adjectives have syncretism between the feminine and the masculine form, for example stor ‘big’ in masculine and feminine, and stort in neuter. The adjective liten has a suppletive paradigm in which the plural form is små.

Finally, anaphoric pronouns agree in gender with the noun they refer to, but there is variation both between two written standards of Norwegian, Nynorsk and Bokmål, and between dialects. Many dialects, as well as Nynorsk, use a system where anaphoric pronouns agree in gender with their noun: Han ‘he’ for masculine nouns, ho ‘she’ for feminine nouns, and det ‘it’ for neuter nouns.

However, in Bokmål as well as in many dialects that are influenced by Bokmål, the pronouns hun ‘she’ and han ‘he’ are only used to refer to humans (and some animals), while non-living beings and abstract entities are referred to using den ‘that’ for feminine and masculine nouns, and det ‘that’ for neuter nouns.

As mentioned above, gender assignment in Norwegian is rather non-transparent – perhaps one reason that Norwegian children acquire gender relatively late (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015). However, there are some tendencies. Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001) argues that there are a variety of assignment rules that can be used to predict the gender of nouns. These assignment rules are either what Trosterud calls ‘general’, semantic, morphological or phonological. He lists 43 such assignment rules, which we will not describe in detail here. Masculine is the most frequent gender: in the dictionary of Nynorsk, 52% of nouns are masculine, 32% are feminine, and 16% are neuter (Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001:22). In the dictionary of Bokmål, the distribution is slightly different, with 65% masculine, 24% feminine, and 11% neutral, but in both cases the masculine gender is clearly the most frequent. Trosterud argues that the default gender in Norwegian is masculine. That is, Norwegian nouns are masculine in the absence of rules that contradict this (Trosterud Reference Trosterud2001:29). Loanwords are, according to Trosterud (Reference Trosterud2001:49), usually put in the default class. However, loanwords can also get assigned feminine or neuter gender, either based on the semantics or the phonology of the loanword. For instance, the word raid is usually neuter when used in Norwegian, perhaps because semantically similar Norwegian words like slag ‘battle’ and angrep ‘attack’ are neuter. The noun bimbo is attested as both masculine and feminine, probable due to it usually denoting female persons.

Three of Trosterud’s assignment rules are argued (by, among others, Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015) to have high reliability: nouns denoting male humans are masculine, nouns denoting female humans are feminine, and nouns ending in -e are feminine. Some examples of nouns exhibiting this distribution are jente ‘girl.f’, gutt ‘boy.m’, søster ‘sister.f’, bror ‘brother.m’, flaske ‘bottle.f’ and klokke ‘watch.f’.

There are exceptions to these rules. For instance, the compound nouns mannfolk ‘menfolk’ and kvinnfolk ‘womenfolk’ are both neuter, conditioned by the final compound element folk (people, person), which is neuter. Nouns that can be used about people of both biological sexes are usually masculine: elev ‘student’, forelder ‘parent’, gjest ‘guest’, professor ‘professor’, and venn ‘friend’, are all masculine. Nouns denoting occupations are also usually masculine: baker ‘baker’, dommer ‘judge’, lærer ‘teacher’, and so on.

Bokmål and Nynorsk both distinguish between three grammatical genders. Bokmål allows a two-gender system, with a common gender and a neuter gender. Most spoken varieties of Norwegian have three genders. In the majority of cases, nouns are assigned the same gender across dialects, with some variation. For instance, the noun do ‘toilet’, is masculine in many dialects, but neuter in some dialects. The nouns bil ‘car’ and katastrofe ‘catastrophe’ are masculine in most dialects, but feminine in some. Appelsin ‘orange’ and gardin ‘curtain’ can belong to all three genders in various dialects.

Some varieties of Norwegian do not have the three-gender system. For instance, the dialect spoken in Bergen only has neuter and common gender (Mæhlum & Røyneland Reference Mæhlum and Røyneland2012:99), most likely a consequence of language contact in the Hansa period. In many dialects in the southeast of Norway, the masculine and feminine genders are merging (see Lødrup Reference Lødrup2011). The same seems to be happening in the Tromsø dialect (Rodina & Westergaard Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015). The result of this process is that the feminine gender is disappearing, resulting in a two-gender system. The same process is largely completed in Swedish (see Braunmüller Reference Braunmüller, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000 for an overview).

In the dialects where the gender system is changing, the change does not affect all nouns in the same way. Some nouns, especially frequent ones, keep their feminine suffix in the singular definite form, while determiners receive masculine agreement, e.g.:

(20)

(21)

This merger might be seen as both a simplification and a complexification of the grammar of nouns, as Rodina & Westergaard (Reference Rodina and Westergaard2015) note. The number of grammatical genders is reduced from three to two (common and neuter); however, within the common gender, there is an additional complexity, in that there are now two possible definite suffixes for the common gender, -en and -a.

3.2 Diminutives in Norwegian

Norwegian has no productive evaluative morphological markers expressing diminutive, but both liten, in the definite form lille ‘small.sg.def’ and the plural form små ‘small.pl’ may to some extent occur as the first element of compounds to express diminution. In these compounds, lille ‘small.sg.def’ often express age (lillebror ‘little brother’), or size (lillefinger ‘little finger’, lilletå ‘little toe’). The same meaning is expressed by the plural form små, in compounds such as småhus ‘small house’, småbil ‘small car’, småfolk ‘small people’ (i.e. babies or children), and småjente ‘small/young girl’.

Skommer (Reference Skommer2016) contains an overview of similar constructions in Norwegian, and he discusses a construction with the noun dverg ‘dwarf’, used as the first element of compounds (dvergbjørk ‘small birch’, dvergplanet ‘small planet’, and dverglaks ‘small salmon’). There are also some suffixes with diminutive meanings in Norwegian, as described by Skommer (Reference Skommer2016). He points out that there are some derivational affixes of limited productivity that convey a diminutive, affectionate or pejorative meaning, -ling in nouns such as killing ‘young goat’, elskling ‘beloved’, mannsling ‘small, weak man’, pusling ‘weak, small person’, jypling ‘young person who thinks he or she is really great’. There is also an affix -lill, that can attach to proper names ‘Frøydis-lill’, ‘Åsmund-lill’, which conveys affection. There is also a synchronically unproductive derivational affix -ett, as in sigarett ‘cigarette’, which stems from a diminutive source. However, the standard Norwegian way of expressing diminution is analytical.

4. The present study

4.1 Goals and research questions

The overarching goal of the current study is to investigate the properties of the Norwegian ei litta construction, looking at both its form and its function, as well as to relate the ei litta construction to cross-linguistic studies of the diminutive. Specifically, we ask the following questions when approaching the data:

1. Form: Which nouns occur in the ei litta construction?

2. Function: What are the semantic and pragmatic effects of using the construction?

In order to address research question 1, we analyzed examples of the construction in a corpus. We then looked at the meaning of the sentences the construction occurred in, and categorized them according to Jurafsky’s categories (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996). However, it is difficult to separate out the semantic/pragmatic effect contributed by the ei litta construction specifically by doing this. In order to assess the specific contribution of the ei litta construction, we conducted a survey, where we asked informants about their intuitions regarding the semantic/pragmatic effect of the construction. In the following, we describe the design and implementation of the two studies.

4.2 Preliminary investigations

As a preliminary method of collecting data, we performed Google searches for the string ‘ei lita/ei litta noun’, where ‘noun’ was replaced with various nouns. We started using nouns we were already aware of occurring in the construction, such as tur ‘trip’ and time ‘hour’. We then expanded the search by substituting neuter and masculine nouns we suspected might occur in the construction. There were hits for many of our test strings, suggesting that the construction is indeed productive. Some hits were from prescriptivist discussion forums, where users expressed frustration over what they viewed as an incorrect way of speaking. It thus seems that the construction is productive and is used sufficiently for speakers to notice it as a new phenomenon. On this basis, we decided to use tagged text corpora to perform systematic searches.

4.2.1 Choosing a corpus

Using corpora in linguistic research gives the opportunity to study ‘language data on a large scale’ (McEnery & Hardie Reference McEnery and Hardie2011), and this is especially the case since most modern electronic corpora are annotated with information such as word class, syntactic function, and other grammatical information. The primary data source for the current project is the electronic corpus NoWaC, ‘Norwegian Web as Corpus’ (Guevara Reference Guevara2010). The NoWaC corpus is POS-tagged with the Oslo–Bergen tagger (Hagen, Johannessen & Nøklestad Reference Hagen, Johannessen, Nøklestad, Lindberg and Lund2000), a morphosyntactic tagger that provides grammatical information for every token in the corpus. The tagger uses a dictionary from Ordbanken ‘The Word Bank’, an electronic database of lexical units.

NoWaC consists of text collected by web crawlers searching the no internet domain (for technical details, see Guevara Reference Guevara2010). It contains approximately 700 million tokens, making it one of the largest existing corpora of written Norwegian available today. The types of texts included in NoWaC makes it well suited to the current study: NoWaC contains both edited texts (newspaper articles, text from official websites of companies and government agencies, books), and unedited text (personal blogs, discussion forums, comments fields of news articles); preferred since more innovations such as ei litta, judged incorrect or non-standard (see Section 5.2.2.3) may be edited out of formal genres. We also searched for the construction in three spoken language corpora, which will be described below.

4.2.2 Search strings and data cleanup

We searched NoWaC using the following criteria: strings starting with either ‘ei lita’ or ‘ei litta’ plus nouns that are classified by the tagger as either masculine or neuter. This yielded 284 hits, which had to be manually cleaned up. We removed hits where the noun could be either feminine or masculine depending on the dialect of the language user, as there is no way to know the dialect background of the language users producing the sentences. This was done to make sure we captured only instances of the construction with the evaluative meaning, not just any combination of the words ei litta and a noun. To determine which nouns can also be feminine, we used a dictionary of Norwegian.Footnote 3 A corpus search for ‘ei litta/lita ADJECTIVE noun (M, N)’ was also performed, but yielded no results.

There were also some hits where the noun in question was a compound written with a space between the elements, and where the final element was actually feminine, as in (22):

(22)

These hits were also removed, as compound nouns in Norwegian always correspond with the grammatical gender of the final element, since compounds are as a rule, right-headed.

In addition to the NoWaC corpus, we searched for the construction in three spoken corpora: The Big Brother corpusFootnote 4 from 2009, containing speech material from 2001, the NoTa corpus,Footnote 5 with material from 2004–2006, and the Nordic Dialect Corpus (Johannessen et al. Reference Johannessen, Priestley, Hagen and Åfarli2009). The Big Brother corpus contains material from speakers from all over Norway, and the Nordic Dialect Corpus contains material from speakers from all over Scandinavia, while NoTa contains material from speakers from Oslo and the surrounding area. Compared to NoWaC, all of these corpora are rather small – the BigBrother corpus contains 440,300 tokens, NoTa contains 957,000 tokens, and the Nordic Dialect corpus contains approximately three million tokens.

Neither NoTa nor the BigBrother corpus yielded any instances of the ei litta construction, while the Nordic Dialect corpus yielded one hit, with the noun kjerne ‘core’. The noun kjerne may be feminine for this speaker, since kjerne can be feminine in this speaker's dialect.Footnote 6 We will therefore not consider this example any further.

4.2.3 Data categorization and analysis

We analyzed the data according to three criteria: whether the noun in the construction was abstract or concrete, which semantic class the noun belonged to, and the meaning of the construction. The two first criteria were used to assess whether there are any restrictions on the construction based on the type of noun. The third criterion was chosen to assess the semantic effect of using the construction on the utterance.

The first criterion, namely classifying nouns as abstract or concrete, was simply ‘can the referent of the noun be touched or not?’ The nouns that were judged to refer to touchable entities, such as kattunge ‘kitten’ and tånegl ‘toenail’, were classified as concrete, while nouns judged to refer to non-physical entities, such as måned ‘month’ and tanke ‘thought’, were classified as abstract.

The second criterion, classifying the nouns according to semantic class, was approached using the semantic categories found in WordNet (Princeton University 2009). WordNet is a lexical database of English, and the categories found there (called senses) have been used in various corpus studies and computational linguistics projects (see Miller & Fellbaun Reference Miller and Fellbaum1998 for more details). The senses used in WordNet are: animal, artifact, attribute, body, cognition, communication, event, feeling, food, group, location, motive, object, person, phenomenon, plant, possession, process, quantity, relation, shape, state, and substance. When classifying the Norwegian nouns into these categories, we looked up which sense the closest English translation had in the WordNet database. This turned out to be unproblematic, as all the nouns had English counterparts with similar meanings.

The third criterion was assessing the meaning of each instance of the construction, using Jurafsky’s (Reference Jurafsky1996) categories, as described in Figure 1. Both authors classified the constructions independently of each other, trying to judge the specific semantic or pragmatic contribution of the ei litta construction, and the annotations were then compared. Some instances of the construction clearly instantiated only one of Jurafsky’s categories, while others could be said to instantiate more than one. For instance, several instances of the construction had both a meaning fitting both the ‘affection’ and the ‘size’ meaning. We therefore tagged each construction with as many meanings as it can be said to instantiate.

4.3 The survey

Gauging the pragmatic effect of a construction is difficult, as discussed by e.g. Borthen & Knudsen (Reference Borthen and Knudsen2014), and the ei litta construction is no exception. We therefore decided to supplement our analyses by using the intuitions of informants. In order to investigate speakers’ intuitions about the use of ei litta, we designed a questionnaire to elicit semantic differences between ei litta NOUN and en liten NOUN in otherwise identical sentences. A written questionnaire was chosen over an oral one in order to make data collection more efficient, bearing in mind the well-known limitations connected to self-reporting. Students from four different university classes in the south of Norway were asked to participate, through a link to the questionnaire.Footnote 7

The purpose of the questionnaire was to assess the pragmatic effect of the construction, and it consisted of three parts. In the first part, the informants were asked to name six different objects seen in pictures, two from each grammatical gender. This was done to check whether each informant uses the feminine gender in his/her dialect. The pictures showed the following objects in a randomized order: a girl (ei jente, feminine), a clock (ei klokke, feminine) a cat (en katt, masculine), a car (en bil, masculine), a house (et hus, neuter), and an apple (et eple, neuter).

The second, main part of the questionnaire consisted of five pairs of sentences, identical except that one sentence had standard adjective–noun agreement and one contained the ei litta construction. The sentences were taken from the NoWaC corpus, and are presented in Section 5.2 below. The ordering of the two was random. The informants were asked to state what, if any, differences in meaning there was between the two sentences, in an open text box. Since the task of describing semantic differences can be challenging, we did not want to present the informants with too many sentence pairs.

In the third part, the informants were asked to answer questions about their age, gender, and dialect background, and whether or not they themselves could use the ei litta construction in their speech. Each part had to be completed before the informants could move on to the next part.

Before choosing whether or not to participate, the students were informed that their participation was voluntary, and that the study’s aim was to investigate a linguistic phenomenon. The instructions stressed the fact that there were no right and wrong answers, and that the informants should write what they intuitively thought when presented with the sentences. Details about the specific topic of the study were not disclosed before participation, but the informants were told they were free to ask further questions by contacting the researchers if they wished.

Thirty-five informants participated, 25 male (71.4%) and 10 female (28.6%), most of whom reported speaking an ‘eastern Norwegian’ dialect. Some of them were more specific, mentioning their town or county of origin, such as Tønsberg, Vestfold, Sandefjord, etc. Three informants were from Bergen on the west coast, two reported speaking a southern Norwegian dialect, and two reported speaking a northern Norwegian dialect.

5. Results

5.1 The corpus study

Initially, we annotated the nouns from the NoWaCcorpus according to whether or not they denoted abstract or physical entities (the criterion used was rather simple, if an entity can be touched it was annotated as concrete, if not, it was annotated as abstract). The reason for annotating this was to see whether there were any particular tendencies. If, for instance, the majority of nouns occurring in the construction had denoted concrete, physical entities, this could mean that physical size is a dominant meaning of ei litta. On the other hand, the presence of nouns denoting abstract entities points towards other meanings of the construction than exclusively physical size, since abstract entities are less likely to have sizes per se (although they can have a duration in time, which can be metaphorically conceptualized as physical size). We found that abstract and concrete nouns both occurred in the construction (56% concrete, 44% abstract).

In (23) and (24), we see examples of the construction used with a concrete and an abstract noun, respectively.

(23)

(24)

5.1.1 The semantic category of the nouns

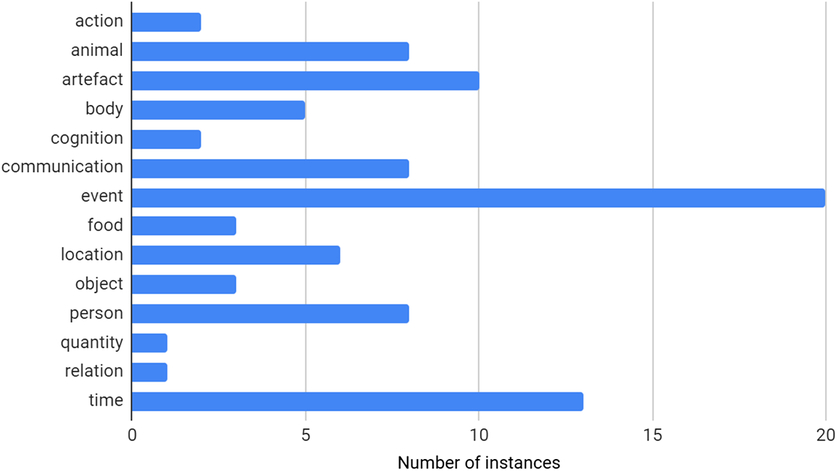

As described above, we categorized the nouns in the construction by semantic type, using the noun senses found in WordNet (Princeton University 2009). As Figure 2 shows, nouns denoting events and nouns denoting time were most frequent in the construction, with 20 and 13 nouns, respectively. Nouns denoting artifacts occurred 10 times, while nouns denoting animals, communication, and persons had eight instances each. A list of all the nouns is available in the appendix. Examples (25)–(30) below show instances of each of these types of nouns (from the NoWaC corpus; the relevant nouns are set in bold).

Figure 2. Distribution of the nouns in the construction by semantic category.

(25)

(26)

(27)

(28)

(29)

(30)

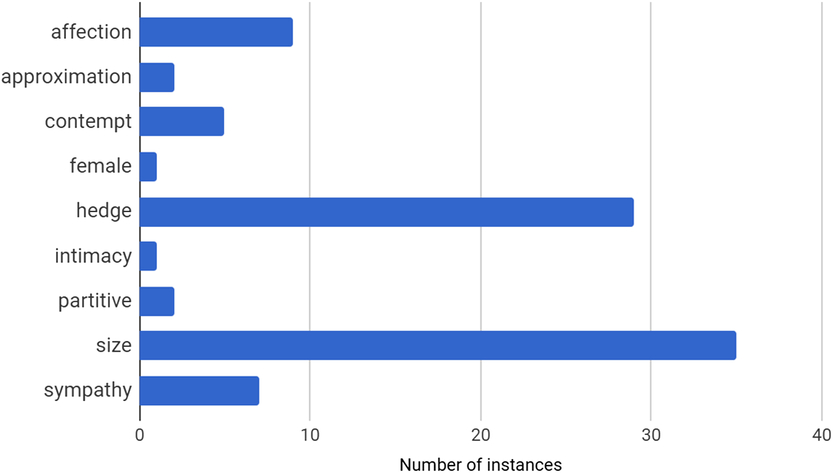

5.1.2 The function of the construction

We categorized the function of the construction itself in context using the categories suggested by Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky1996) and shown in Figure 1 above. The results are shown in Figure 3. As evident in Figure 3, some functions were much more frequent than others in the data. The most frequent function was ‘size’, then ‘hedge’, ‘affection’, ‘sympathy’ and ‘contempt’, with the other observed functions being less frequent. Examples of some of the functions are exemplified in (31)–(36).

Figure 3. Function of the construction in the collected data.

(31)

(32)

(33)

(34)

(35)

(36)

Our findings align with Jurafsky’s (Reference Jurafsky1996) model of diminutives regarding the distribution of the functions associated with the construction. Signaling ‘small size’ is the most frequent function of the construction. Since the lexical source of the ei litta construction is an adjective meaning ‘small’, this is perhaps unsurprising.

5.2 Results of the survey

5.2.1 Informants’ use of the ei litta construction

Of the 35 informants, 16 reported using the ei litta construction. Some of these informants qualified this by stating that they only use it ‘in certain contexts’. Two additional informants reported using it ‘to make fun of’ eastern Norwegian dialects. The informants who reported using the construction provided intuitions about its meaning, as did some of the informants who did not use it themselves, as will be detailed below. The informants who reported using the construction nearly all had dialects that are classified as eastern Norwegian dialects (Drammen, Sandefjord, Telemark, and Tønsberg were explicitly mentioned), while some informants simply reported speaking ‘eastern Norwegian’ or ‘close to Oslo dialect’. One informant reported having a ‘mixture’ of dialects, having lived in six different counties, and one reported being from Bergen (on the west coast), but wrote that his speech was influenced by eastern Norwegian because he had lived in the area for many years. The informants who reported a semantic/pragmatic difference between the sentence pairs did not all use the construction themselves, indicating that speakers may be aware of the construction’s meaning without using it.

The gender ratio for the informant group as a whole was 71.4% female and 28.6% male (25 vs. 10 informants). For the informants who reported using the ei litta construction, there was a similar gender ratio but with a slightly higher proportion of female respondents: 75% of the informants who reported using the ei litta construction were female and 25% were male (12 vs. 4 informants).

Some of the speakers who reported that they used the ei litta construction appeared to use feminine gender in their speech in other contexts. When asked to name the objects in part one of the questionnaire, eight of the 16 informants who reported using the ei litta construction used feminine gender morphology with both nouns (klokke ‘watch’ and jente ‘girl’). Four informants did not use feminine gender morphology. One informant excluded any markers of grammatical gender, and three informants used feminine gender morphology for jente ‘girl’ but not for klokke ‘watch’.

5.2.2 The semantic and pragmatic effects of ei litta

The second, main part of the questionnaire consisted of five pairs of sentences, identical except that one sentence had standard adjective–noun agreement and one contained the ei litta construction. The ordering of the two was random. The informants were asked to state what, if any, differences in meaning there was between the two sentences, in an open text box, of the sentences (37)–(41):Footnote 8

(37)

(38)

(39)

(40)

(41)

In the following, we describe the types of responses we got on the survey, and we summarize the findings in Table 2. Note that nonsense responses, such as one informant only responding by typing the letter ‘b’, were discarded, as were blank responses. The quotes from the informants have been translated to English. Many informants gave different judgments for each sentence pair. The responses describing pragmatic or semantic differences will be qualitatively described, with examples from the responses, while the responses that do not report a semantic or pragmatic difference between the sentences will also be analyzed quantitatively. When quantifying the responses, we report on all informants’ responses for each sentence pair, amounting to a total of 175 responses (35 informants × 5 sentence pairs).

Table 2. Survey responses. White rows indicate responses that did not specify any semantic or pragmatic difference. Gray rows indicate responses that reflected a semantic or pragmatic difference.

5.2.2.1 No difference and form-focused responses

Around 23% of the responses (40 out of 175) explicitly reported no difference between the sentence pairs, either writing that there is no/little difference, or that the sentences are ‘the same’. Some informants did report a difference, but not a difference that was semantic or pragmatic in nature, and we can call these responses ‘form-focused’. These informants simply stated the difference in form between the standard agreement sentences and the ei litta sentences, for instance by writing that ‘the adjective in sentence a) is feminine but the adjective in sentence b) is masculine’. Eleven out of 175 responses (6%) were form-focused.

5.2.2.2 Normative responses

Some informants gave what we have called ‘normative responses’, where they either said that the ei litta version of the sentences were ‘wrong’, that they ‘sound strange’, ‘I would never say this’, ‘sounds unnatural’ or similar. One informant reported that they would ‘correct’ the ei litta version of the sentences. Seventeen out of 175 responses (9.7%) were of this type.

5.2.2.3 Register-focused responses

Another category of responses can be called ‘register-focused’. The responses in this category stated that the ei litta sentences were ‘dialectal’, something found ‘only in spoken language but not in written language’, that the ei litta sentences could only be uttered by ‘younger people’, or that they were ‘slang’. Fourteen out of 175 responses (8%) were of this type.

The categories of responses described so far (explicitly stating that there was no difference, normative responses, form-focused responses, and register responses), account for around 46% of the responses (82 out of 175 responses). The rest of the responses described what we interpreted as a difference in function of the ei litta sentences.

5.2.2.4 Explicit, but unspecific reference to semantic/pragmatic effect

Some informants did have an intuition about the function of the construction, but did not formulate any specific semantic or pragmatic contribution, only that the size of the object denoted by the noun was somehow ‘less important’. For example, one informant reported, responding to the ‘heartbreaker’ sentence (37), that the version with ei litta meant that the person in question was ‘quite a heartbreaker’, while the version with standard gender agreement specifically referred to the physical size of the person in question. Another informant wrote about the ‘heartbreaker’ sentence that the person being described in the ei litta version is ‘cute, not just little’. Several informants commented on the ‘beer’ sentences (41) that the sentence with en liten beer implied having one and only one beer, while drinking ei litta beer could result in excessive drunkenness (one informant wrote that if you are having ei litta beer, you can easily end up ‘drunk in a ditch’). These types of responses were classified as ‘unspecified difference’.

5.2.2.5 Size-focused responses

Seemingly opposite to the ‘unspecified difference’ responses were the responses that emphasized small size in the ei litta sentences. Especially for the ‘car ride’ sentence (40), speakers reported that the ei litta version of the sentence conveyed a smaller size than the standard agreement version. One informant wrote that ‘the car ride in the ei litta sentence is smaller’. Another informant wrote that in the ei litta sentence, the distance is ‘shorter’. This response category was labeled ‘size’.

5.2.2.6 Hedge-focused responses

The responses of this type described the difference between the sentences by pointing out that they perceived the sentences with the ei litta construction as ‘less serious’, ‘more playful’, ‘joking’, ‘less formal’ or similar.

In this category we have also put responses that described the difference between the ei litta sentences and their standard counterparts focusing on how ‘important’ the entity being described was. For instance, one informant contrasted the standard and the ei litta versions of the ‘ask a little question’ sentence (38) by saying that the ei litta variant posed a ‘less important’ question. Another informant called the question in the ei litta version ‘smaller’, which in this context can be interpreted as less significant, or less threatening. Another informant wrote that the standard version was ‘literal’, while, in the ei litta version, the speaker is going to ask for a favor. Another informant described the standard version of the sentence as ‘more authoritative’. Regarding the ‘car ride’ sentence (40), an informant commented that when uttering the ei litta version of the sentence, the speaker is making the distance of the car ride less significant. Describing the ‘gym selfie’ sentence (39), one informant wrote that a speaker posting ei litta selfie is more modest, and afraid of a negative response.

5.2.2.7 Intimacy-focused responses

Some responses focused on the relation either between the speaker and the listener or between the speaker and the person being described. For instance, one informant wrote that when using the ei litta version of the ‘beer’ sentence (41), it was more likely that the speaker had a ‘good relation’ to the person being invited to have a beer. One informant reported that regarding the ‘heartbreaker’ sentence (37), the ei litta version ‘describes a relation that is closer’ than in the standard agreement version.

5.2.2.8 Affection/sympathy-focused responses

Another type of response emphasized the degree to which the described event or entity was ‘cozy’ or enjoyable. For instance, one informant writes about the ‘car ride’ sentences (40) that the ei litta variant implies a ‘spontaneous cozy trip’. Another informant writes that the ei litta car ride sounds ‘mer koseligere’ ‘more cozier’. Yet another informant reports that the car ride in the ei litta version ‘will be fantastic’.

5.2.2.9 Summary of survey results

Table 2 summarizes the types of responses and compares them to Jurafsky’s categories where relevant. The first three categories of responses do not directly address any perceived semantic or pragmatic differences and will not be discussed further. The fourth, ‘register-focused’, category might be interpreted pragmatically, as using a different register certainly can have pragmatic effects, and the informants’ intuitions that the construction belongs to certain registers is consistent with what is already known about the construction: it is associated with a certain geographic area (southeast Norway), with a certain age group (younger individuals), and with spoken language in informal situations.

The ‘size’ responses correspond to the core meaning of the construction, a diminutive meaning, and this is not surprising considering the lexical meaning of the adjective litta. However, it is interesting that the informants indicated that in the minimal sentence pairs, the ei litta versions of the sentences implied an even smaller size than the corresponding sentences with the standard gender agreement.

The ‘hedge’ type responses included both responses that described the ei litta sentences as ‘less serious’ or ‘more playful’, and responses that described the person uttering them as ‘more modest’ or ‘asking for a favor’. All of these responses have been interpreted as describing the pragmatic function of hedging.

The ‘intimacy’ and the ‘affection/sympathy’ responses correspond to the identically named categories in Jurafsky’s classification.

5.3 Exploring the diachronic dimension

In order to address the diachronic aspect of the construction, we performed a search on Twitter. Due to terms of service restrictions put in place by Twitter,Footnote 9 a manual web search was performed using Firefox. We used the advanced search options to choose ‘latest tweets’ and then restricting the search to one year at a time. The resulting pages were saved as web pages. Then, Python 3 and the library BeautifulSoup were used to parse the resulting HTML to extract hits as plain text.

While the electronic corpora employed provided a relatively restricted amount of relevant ei litta tokens, this was not the case for Twitter. We searched for public tweets containing the string ‘ei litta’, from 2008 to the present. Only the spelling ei litta was included; this was a measure both to make the manual handling of the data possible (before the cleanup, the ei litta hits amounted to 2906), and due to the fact that Twitter, unlike the NoWaC corpus, does not offer advanced search options. After removing hits where the noun was feminine, and identical tweets, using the same inclusion criteria as for the NoWaC data, 1886 hits remained.

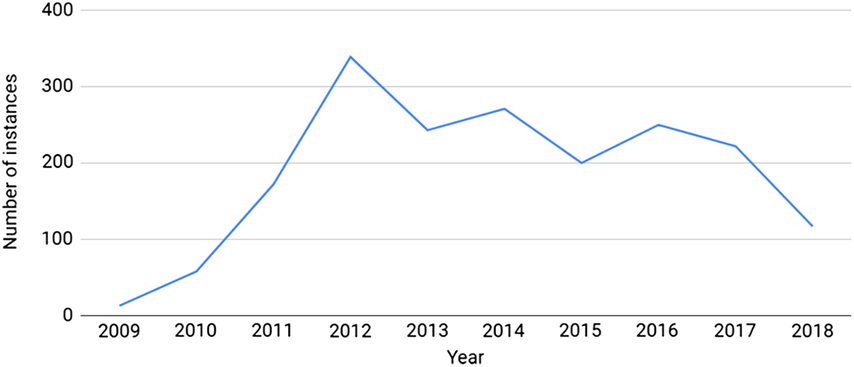

Figure 4 illustrates the number of uses of ei litta with masculine and neuter nouns per year. The first attested instance of the construction was in 2009, and the number of instances increased sharply until 2012, when it seems to have stabilized or fallen slightly in popularity. In itself, this fact is interesting: as is often the case for what is perceived as new constructions or innovations, they have in fact existed for quite some time when linguists become aware of them. For the year 2018, only tweets from January till July were counted.

Figure 4. Attested instances of ei litta on Twitter.

An additional interesting fact is that it seems clear from these numbers that the ei litta construction predates the TV series SKAM. The series, which aired in 2015, is often associated with the popularity of the construction; it was frequently used by the series’ heroine Noora. However, the Twitter data indicates that the use of the construction is indeed an Internet phenomenon. The construction might of course predate 2009, but as mentioned in Section 4.2.2 above, we did not find any hits for the construction in corpora predating 2010. Twitter as a social media platform came into being in 2006, and the lack of tweets containing the construction before this time might partly be due to fewer people using Twitter.

5.4 A note on productivity

Aside from the quantitative dimension, a noticeable finding in the Twitter corpus was the large number of non-established loanwords occurring in the tweets that used the ei litta construction. Four hundred and twenty-eight of the hits (23%) contained English nouns in the construction. While Norwegian has adopted a large number of English loanwords, these English nouns were striking because they were words that had not been integrated into Norwegian neither in spelling, pronunciation, or morphology. The nouns (for instance nouns like powernap, follow, sugahdaddy, funfact, and update) could be viewed as instances of code-switching. If integrated, one would expect these nouns to be assigned the masculine gender in Norwegian, since it is usually the case that loanwords are assigned as masculine, as mentioned in Section 3.1. The only one of these examples that appears in the Norwegian dictionary we used (ordbok.uib.no) is chat, which is indeed masculine.

These nouns tell us two important things. First, since these nouns have no assigned gender in Norwegian, we can be sure that their use with ei litta is not a dialect feature. Second, the fact that they are included in the construction illustrates its productivity with new nouns.

6. Discussion

In the previous sections, we presented the first systematic observation of how gender shift in the ei litta construction expresses evaluation in Norwegian. What do these findings tell us? Here, we first discuss the construction’s form and function, how it relates to cross-linguistic findings on evaluative morphology, and ultimately its role in the larger restructuring of the Norwegian gender system.

6.1 The form of the ei litta construction

The ei litta construction consists of a gender shift from masculine or neuter to feminine, together with the adjective litta ‘small’, which may be said to function as an analytic way to express diminutive meanings. Both masculine and neuter nouns can take part in the construction, but masculine nouns are more common – probably because neuter nouns are less frequent overall. All types of nouns seem to be able to occur in the ei litta construction, there are no obvious semantic restrictions. In our corpora, both concrete and abstract nouns occurred, as well as nouns with a range of semantic senses. Most common were nouns denoting time periods and events.

6.2 The functions of the ei litta construction

Figure 5 illustrates the identified functions of the ei litta construction from the corpus study. The size of the circles is an approximation of the relative frequencies of the different functions. The categories identified by the informants in the survey study were ‘size, ‘intimacy’, ‘hedge’, and ‘affection/sympathy’, and were thus a smaller subset of the categories identified in the corpus part of the study. These findings are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 5. Overview of the semantic categories in the Norwegian ei litta construction.

Table 3. The semantic and pragmatic meanings of the Norwegian ei litta construction

The categories shown in the Norwegian data (Figure 5) are a subset of the categories proposed by Jurafsky (Reference Jurafsky1996), as presented in Figure 1 above. The functions of the Norwegian ei litta construction all belong on the ‘pragmatic’ side of Jurafsky’s model. While the ‘core function’ of the construction is to signal that the referent has a ‘small size’, the extended functions beyond this are all in the pragmatic domain of Jurafsky’s semantic map. In other words, the use of the ei litta construction is often to signal the speaker’s attitude about the entity denoted by the noun, whether that attitude is sympathy, affection, or contempt. In addition, the construction is often used as a hedge, that is, to soften the implications of the statement being put forth.

Figure 6. The attested uses of the Norwegian ei litta construction.

In Figure 6, Jurafsky’s model (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996) is used to illustrate the attested functions of the Norwegian ei litta construction. It seems in other words as if the Norwegian construction displays some, but not all, of Jurafsky’s (Reference Jurafsky1996) categories. It is noteworthy that the ei litta construction expresses a range of meanings described in Jurafsky’s model, and it thus seems to fit his model well.

It is noteworthy that 16 informants report that they use the construction, and that many informants who do not use the construction themselves have intuitions about its function. The fact that they do so in a formal questionnaire suggests that the construction has reached some level of conventionalization. This is also supported by the fact that some informants who report that they do not use the construction themselves but could use it to ‘mock’ or imitate the eastern Norwegian variety. These speakers are not only familiar with the construction, but they associate it with a particular dialect.

The reported semantic and pragmatic effects of the constructions to a large degree correspond with the functions found in the corpus examples. The hedging function, exemplified by the responses where informants mentioned something being ‘less important’ is common and seems to be a central function of the ei litta construction.

6.3 Typological considerations

From a typological perspective, the Norwegian construction fits well with what we know about diminutive constructions cross-linguistically; they express a range of meanings, some of which appear contrary: affection and sympathy vs. contempt, for example. This complexity of meaning is captured in Jurafsky’s model, a model that proves useful in the analysis of the Norwegian construction. The construction also illustrates the relation between feminine gender and diminutive meaning, although the explicit combination of the two, as we see in the ei litta construction, has not been documented for Norwegian.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the findings indicate that in the ei litta construction, Norwegian has what Di Garbo (Reference Di Garbo2014) calls ‘manipulable gender’. According to Di Garbo, the existence of such manipulable systems indicates that gender assignment is less rigid than typically assumed and raises questions about whether gender should be viewed as an inherent property of the noun or not (Di Garbo Reference Di Garbo2014). In such systems, gender shift is a productive process that allows the speaker to assign new meaning to a word, solely by changing its gender. Although this manipulation is not a feature of the Norwegian gender system as a whole, in this specific construction, the speaker may manipulate the gender to achieve certain semantic and pragmatic effects.

6.4 Ei litta and grammaticalization

Some scholars view the development of diminutive markers as instances of grammaticalization, specifically a development from the concrete meaning of small size, to one of intensification of abstract qualities, triggered by metaphor and other semantic/pragmatic mechanisms (Mendoza Reference Mendoza2011). This grammaticalization is visible, states Mendoza, in the much-described uses of the Spanish diminutive in constructions like detrasito ‘right behind’ vs. detras ‘behind’ and afuerita ‘right outside’ vs. afuera ‘outside’. A similar analysis has been made for the Norwegian ei litta construction. Opdahl (Reference Opdahl2014) argues that the ei litta construction provides an example of a grammaticalization path, in which the lexical item goes through a number of changes associated with grammaticalization. These are semantic bleaching, phonological reduction, expansion of usage domain, as well as, and importantly, the passage from lexical to grammatical meaning. Opdahl further argues that the change in meaning and usage of ei litta is best described as an instance of pragmaticalization, since its current use is associated with adding pragmatic meaning rather than being a purely grammatical marker. Our data do not indicate that ei litta is undergoing grammaticalization, as the novel meanings identified are not grammatical in nature.

6.5 Ei litta and the restructuring of the Norwegian gender system

We are currently witnessing a restructuring of the Norwegian gender system. Use of the feminine indefinite article is becoming less frequent – and indeed is obsolete already in many varieties. If the feminine gender is losing terrain, how can it simultaneously be used productively in a novel way? One explanation is that the low frequency of the feminine indefinite article ei is likely to make its use more marked. This in turn may explain why this marker has become the origin of a novel meaning. Still, informants in the survey largely report both the use of the feminine form, and the use of ei litta.

7. Conclusion

In this article, we have discussed three aspects of the Norwegian ei litta construction. We have observed that both concrete and abstract nouns are used in the construction, and that nouns meaning time periods and events are most commonly used. We have observed that the meaning of the construction to a large extent overlaps with the radial model of diminutive construction proposed by (Jurafsky Reference Jurafsky1996). We have also seen that that from a typological perspective, diminutive and feminine morphology is often applied to express evaluative meaning. However, we have seen that using a combination of the two, as in the Norwegian ei litta construction, is typologically rare and previously unaccounted for in Norwegian.

Furthermore, we have discussed the emergence of the ei litta construction in the light of a larger restructuring of the Norwegian gender system, possibly allowing for greater flexibility in the assignment of gender. We have also described the ei litta construction as an example of gender shift; a previously unattested morphological strategy in Norwegian to express evaluative meaning. This strategy points to both a complexification of the Norwegian gender system, through a hitherto unproductive morphological strategy, as well as a less rigid gender assignment, that points to a more dynamic gender system in Norwegian.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the editor Marit Julien, as well as three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. We also wish to thank the students who participated in the survey and audiences at conferences in Bergen, Copenhagen, Oslo, Paris, Tallinn, and Tel Aviv. The usual disclaimer applies.

Appendix

The nouns found in the ei litta construction (NoWaC)

The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of instances of the construction with the noun in question, for the nouns that occurred more than once.