The effect of [Saccardo's] work illustrates again the fact that progress in botany, as in other sciences, is based not only on brilliant research and broad generalization, but also on a large amount of downright drudgery.

J.J. Davis, 1920The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) ‘Red List’, which inventories the extinction risk of biological species around the world, is one of the central documents in contemporary conservation politics, shaping funding and environmental priorities for governments and international organizations. Yet prior to 2016, fungi, which are some of the most ecologically significant and diverse organisms on earth, were essentially unrepresented: not long ago, the Red List contained 20,000 species, only three of which were fungal (two lichen and one mushroom). This is not because fungi are not endangered, but because the extent and distribution of many species remains poorly understood.Footnote 1 At an even more basic level, the question of exactly how many fungi there really are continues to puzzle biologists.

In 1993, American botanists Clyde Reed and David Farr published an eight-hundred-plus-page index to Italian mycologist Pier Andrea Saccardo's Sylloge Fungorum Omnium Hucusque Cognitorum. Composed of 28,000 pages in twenty-six volumes, and produced between 1882 and 1931 (a final, delayed volume arrived in 1972), the Sylloge, as it is often shortened, was Saccardo's attempt to collect names and descriptions for every known species of fungi.Footnote 2 Written in botanical Latin (its title could be rendered ‘Gathering of All Presently Known Fungi’), and with many volumes more than a century old, it is less than obvious why scientists at the close of the second millennium would conduct such an expansive and tedious project of reindexing. However, ‘This consolidation of information from numerous publications remains a valuable tool for practicing taxonomists’, Reed and Farr explain, allowing one to ‘quickly locate a copy of the original description and a reference to the place of publication’, which was especially useful ‘for the taxa described in obscure journals and for taxonomists lacking access to the full range of mycological literature’.Footnote 3 Despite a number of missing species, collected by the United Kingdom's Commonwealth Mycological Institute in Saccardo's Omissions (1985), in 1993 the Sylloge remained ‘the only comprehensive listing of fungal taxa’.Footnote 4 How could this possibly be? What made Saccardo's project so all-encompassing and so unsurpassable?

Figure 1. Pier Andrea Saccardo walking in front of the Orto Botanico di Padova, 1906, albumen silver print, Gallery of the Botanical Gardens, PHAIDRA Digital Collections, Università di Padova - Biblioteca dell'Orto botanico.

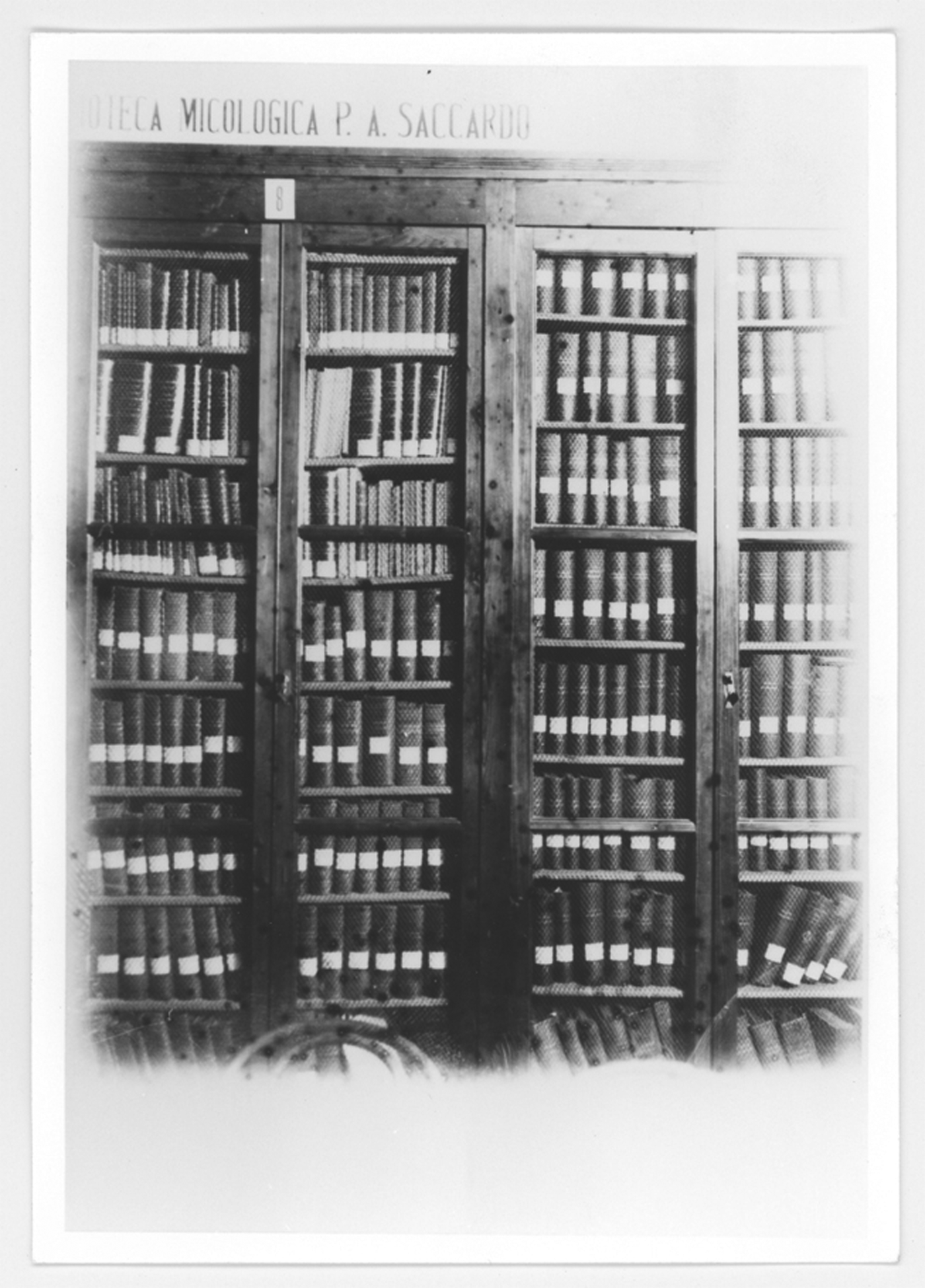

Figure 2. The Mycological Library of Pier Andrea Saccardo, c. 1925, gelatin silver print, Gallery of the Botanical Gardens, PHAIDRA Digital Collections, Università di Padova - Biblioteca dell'Orto botanico.

This article offers an answer, situating the Sylloge within Saccardo's professional dive into cryptogamic botany (the study of ‘plants’ which reproduce by spores) and mycology's emergence as a distinct field of scientific inquiry. When Saccardo began university studies in Padua in the 1860s, mycology was a subset of botany, taught not as a science but as a course in conventional medical training. Like many others at the time, Saccardo came to mycology as an amateur, interested in collecting, drawing and examining fungi, but by the time he became director of Padua's Botanical Garden just two decades later, cryptogamic botany had become a quasi-independent scholarly undertaking.Footnote 5 Taking Saccardo's life as an entry point, this essay explores part of a centuries-long transformation in the status of mycology from a marginal, often amateur, study to a vibrant experimental and taxonomic discipline, as partially signalled by the recognition of the ‘kingdom of fungi’ in 1969.Footnote 6

The article analyses how Saccardo's unique social, intellectual and geographical position enabled him to function as a latter-day Linnaeus for mycology, the obligatory passage point for worldwide fungal taxonomy for nearly four decades.Footnote 7 In doing so, I aim to remedy an absence of English-language scholarship on both Saccardo and the history of mycology broadly. As Nathan E.C. Smith notes, most existing histories are practitioner accounts and often consciously motivated to confirm mycology's ‘scientific’ status.Footnote 8 Saccardo was central in the unification of fungal knowledge, which was in turn a subset of larger transformations in the relationship between ‘natural history’ and ‘experimental science’. But he was also quiet and unassuming, evincing a commitment to careful observation so absolute that a friend nicknamed him the ‘Father General of Observing Fungi’ and compared him to a Carthusian monk.Footnote 9 Only the First World War's painful arrival in Italy was able to fully dislodge Saccardo from his work and beloved Padua. Analysing his practice and commitment to place offers vital insight into late nineteenth-century biology.

Second, the article interprets Saccardo's Sylloge as a data management project within the systematizing ‘information science’ of botany, an attempt to cope with the information explosion produced by rapid communication infrastructure and applying newly powerful microscopes to the world's cryptogams.Footnote 10 In the last decade, scholars of science have shown how electronic databases became omnipresent and essential to the work of contemporary biology, simultaneously producing and responding to what some call a ‘data deluge’.Footnote 11 Bruno Strasser argues, however, that these developments represent less a revolution in style and practice than the evolution of ‘of a much longer tradition of collecting, comparing, and classifying objects in nature’.Footnote 12 What databases are to today's experimental life sciences, Strasser argues, museums were to twentieth-century natural history, which allows historians to ask new questions: what is the status of the data collector? Who is responsible for the integrity of the data?

Although many responses to these questions have focused on the informatization of biological bench work in the twentieth century, Saccardo's project was already an attempt at collecting, comparing and classifying that bridged the natural-history tradition with the emergent experimental paradigm. His book, a kind of proto-database, was produced at a moment when there seemed to be too much to know – even in 1892, the possible number of fungi appeared almost incomprehensibly vast – and was an effort to tackle that information overload, systematizing all that was ‘presently known’ for the benefit of researchers around the world. Like Carl Linnaeus, as Staffan Müller-Wille and Isabelle Charmantier have shown, Saccardo's lists served simultaneously as research tools and strategies for tackling information overload.Footnote 13

Yet even more than Linnaeus, Saccardo operated in a transitional moment and a linguistically and politically fractured scientific environment, and his work elucidates one piece of the emergence of what can be recognized, retrospectively, as the international biological ‘database’. Growing up in the province of Veneto, then under Austro-Hungarian control, Saccardo's early taxonomic work is legible as a ‘regionalist’ botany – the most common mode of mycology at the time – focused on appreciating Italy's flora and extolling the contributions of its researchers.Footnote 14 Later, his compilations took on an actively universalizing scope, as Saccardo hoped to create a comprehensive collection of all fungal species. Yet doing so required gathering publications from a plethora of journals, in nearly as many languages, and exhaustively verifying the integrity of his collected data. Sylloge was thus the right name for the project, because Saccardo's book was ultimately a condensed library, enabled by his multilingual correspondence network.Footnote 15

Like Linnaeus's lists, the Sylloge was facilitated by a flood of letters, journals, books and fungal specimens arriving from colonial and settler outposts as well as metropolitan centres around the globe.Footnote 16 Sustaining these exchanges was not without difficulty, but Saccardo succeeded in tying together mycological communities on almost every continent: George Washington Carver asked for his help in identifying Alabama fungi, while Japanese plant pathologists invited him to settle classification controversies over rice parasites.Footnote 17 At the same time, his somewhat anachronistically Linnaean performance of writing exclusively in Latin provided the Sylloge an appearance of border-spanning neutrality that resisted the ‘scientific babel’ threatening to reduce botany to a disorganized multitude of regional studies.Footnote 18 Building on efforts to historicize the modern biological database, we can think of Latin as Saccardo's database language, one enabling queries and modifications by the widest possible set of users as part of a broader project of collecting, coding and classifying. Saccardo made vital steps toward the construction of material and scholarly infrastructure for a ‘global’ mycology, with his Sylloge its first document – one difficult, if not impossible, to replicate.

Portrait of the cryptogamic botanist as a young man

Pier Andrea Saccardo was born on 23 April 1845 in the village of Selva di Montello, north-west of Treviso, as buds began to break at the vineyards. The times of his childhood were tumultuous: a civilian uprising in 1848 against the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire won temporary independence, but control was reversed by June. Unrest persisted until 1866, when the region was annexed into the Kingdom of Italy, but there were few obvious signs in Pier Andrea's childhood. At twelve years old, studying at the gymnasium of the Patriarchal Seminary of Veneto, he grew infatuated with botany, inspired by his uncle Alessandro's orchard. Little survives about his mother, Elena Vidotto, but Saccardo's father, Francesco di Selva, was an engineer, and the family supported their son's wide-ranging interests: by fourteen, he had drafted a herbarium of 130 species, catalogued 150 types of leaves and begun a study of Treviso's crustaceans, insects and molluscs. He gave up the last of these only in 1864 after enrolling at the Royal University of Padua, by which time he had established his own botanical garden, cultivated hundreds of species from the forest of Montello, and begun a comprehensive study of Trevisan flora.Footnote 19

Saccardo's adolescence revealed him to be an impressively capable collector and botanist, one whose talents did not go unnoticed. On 1 November 1866, he became assistant to Roberto de Visiani, Padua's chair of botany and the director of its Botanical Garden, one of the oldest in the world. De Visiani had witnessed the modernization of Italian botany and supported its transformation from a subfield of pharmacy and expected subject of medical study to a quasi-independent branch of natural history.Footnote 20 An accomplished collector, he also expanded the garden's holdings through exchanges with the world's major botanic institutions, rebuilt greenhouse roofs, installed a heating system and won support for a botanical lecture hall. He was well connected to Italian botanists as well as those elsewhere in Europe, and travelled the continent in 1862, visiting the Royal Gardens at Kew and witnessing developments in collecting in France.Footnote 21 Saccardo would have struggled to find a more auspicious guide or location for a career in botany.

Two interconnected arcs marked Saccardo's early scholarly trajectory: a broadening of the geographical scope of analysis and a steady concentration of attention on fungi. His childhood passion for botany had partly been a passion for the flora of Treviso, but as he worked with de Visiani, that purview expanded to an ever-larger area. In parallel, he shifted from broad interest in the ‘higher’ plants to a specialization in cryptogams – the ‘lower plants’, including lichens, mosses, ferns and fungi, which reproduced by spores. In 1867, the year that he married Eleonora Zava and enrolled for his degree with the university's Faculty of Philosophy, Saccardo published a small study of the vascular cryptogams of Treviso. Two years later, he and de Visiani collaboratively issued the Catalogo delle piante vascolari del Veneto (Catalogue of the Vascular Plants of Veneto), an expansion of de Visiani's 1858 vascular plant collection now supplemented with Saccardo's cryptogams.

This work came as cryptogamic botany continued an unsteady rise to prominence in Italy. Giuseppe De Notaris, a talented microscopist at the University of Genoa who wrote in elegant scientific Latin, had founded the Società Crittogamologica Italiana in 1858, but the society struggled to sustain funding and member interest. Publication of its Commentario, which began in 1861, lasted only until 1867. Yet cryptogams, especially fungi, remained of interest to many, not least for their culinary and agronomic prominence – cheese molds, truffles and edible mushrooms were components of everyday life in much of Italy – and species lists of newly identified fungi continued to appear for years after.

Saccardo made his first explicitly mycological contribution with Mycologiae Venetae Specimen (1873), a compilation of Veneto's fungi written in response to Austrian botanist Ludwig Heufler von Hohenbühel's Enumeratio Cryptogamarum Italiae Venetae (Enumeration of the Cryptogams of Venetian Italy) (1871).Footnote 22 The Enumeratio was meant as an initial effort to identify Veneto's cryptogamic flora, and its introduction admitted that little ‘information as to the Cryptogams’ had been ‘sufficiently ascertained’. The exception was a recent study of vascular cryptogams by ‘P.A. Saccardo’.Footnote 23 Hohenbühel acknowledged that his own work remained incomplete and anticipated that an eventual successor might even double his findings.

Saccardo nominated himself to do so. Fungi were ‘so scarcely represented’ in the Enumeratio, he argued, as to be ‘almost completely unexplored’.Footnote 24 The book listed 1,242 species in upper Austria but only 245 in all of Veneto, a disparity Saccardo considered impossible. At issue, in part, was politically charged protectiveness: here was an Austrian baron underestimating the diversity of a region controlled, until very recently, by Austrian rulers. Saccardo stressed his ‘shame’ at ‘seeing our mycological flora’ reduced to so little, and years later would credit Italy's political fragmentation with the delayed emergence of a genuinely ‘national’ botanical history.Footnote 25 But the baron was not the issue here, solely. Most cryptogamic studies of the region dated to the beginning of the century, a time when the analytical focus was on phanerogams (seed-producing plants) and both the maximum resolution and availability of microscopes made the study of spores and microfungi exceedingly difficult. There were very few resources for the baron to draw on in adequately cataloging the cryptogams of Veneto.

What Saccardo found when he began to look, however, surpassed his wildest expectations. Focusing on species near Montello, where his childhood botanical exploits had taken place and the ‘most beautiful, largest and most delicious’ mushrooms could be collected – suggesting, once more, the culinary underpinnings of much mycological curiosity – he was ‘almost drowned’ in a ‘great sea’ of life forms. While ‘sordid’ or ‘plebian’ to the naked eye, they were revealed in all their ‘marvellous’ secrets beneath the eye of his microscope.Footnote 26 Despite a sense that he lacked an overarching method for studying fungi, Saccardo quadrupled Heufler von Hohenbühel's identifications to over a thousand.Footnote 27

In the introduction to his Mycologiae, Saccardo placed himself within a lineage of the world's prominent mycological naturalists: Elias Magnus Fries, who produced the last ‘universal’ catalogue of fungal species, the Systema mycologicum, between 1821 and 1832; Heinrich Anton de Bary, known as the ‘father’ of mycology for his life histories of fungi; the brothers Tulasne, naturalists and creators of some of the most magnificent fungal illustrations; and Karl Wilhelm Gottlieb Leopold Fuckel, who compiled an exhaustive collection of Rhenish fungi. Most central of all for Saccardo, however, was De Notaris: he had offered early advice to the young mycologist, and Saccardo drew on his ‘sporological’ (or ‘carpological’) approach to classification, which distinguished species and genera on the basis of the shape and structure of their spores.Footnote 28 This was the method Saccardo would develop in subsequent works, and his affection for De Notaris never waned: when the Società Crittogamologica Italiana re-formed, Saccardo proposed that its 1878 Acts be dedicated to the great microscopist.Footnote 29 The other leading lights of mycology were nevertheless important, and Saccardo adopted from De Bary and the Tulasnes the then controversial view of fungal ‘polymorphism’ (or pleomorphism), namely that species appeared in various forms at different life stages, which had caused those stages to be misclassified as separate species by earlier naturalists.

Producing mycological lists, Saccardo was quick to admit, required help. While he had collected many specimens himself, he also received assistance of multiple forms: Adolfo de Bérenger, the inspector general of Florence's Ministry of Agriculture, had lent him fungal slides; Giacomo Bizzozero, a gardening student at Padua, collected samples; Caro Massalongo, a botany assistant, acquired still others. The provincial physician of Vicenzia and one of Saccardo's wife's relatives had helped, and so too had Francesco Masè, abbot of Castel d'Ario nel Mantovano. To comb the Italian countryside for specimens of fungal life was a job for more than one man, and Saccardo's reliance on an extended network of collectors and keepers of specialized knowledge would continue throughout his career.

Mycologiae Venetae Specimen appeared, in 1873, just prior to a passing of the botanical guard: De Notaris died in 1877, de Visiani the following year. With leadership of botany in Padua vacant, Saccardo was the obvious successor, having lectured and managed the gardens during de Visiani's sickness and absences. He became chair of botany in 1879, which marked a symbolic moment in botany's shifting scientific status, as Saccardo was the first to hold a degree in philosophy rather than medicine.Footnote 30 As the story goes, Saccardo was examining a fungus that grows on bay laurels when he received news of the appointment and celebrated by christening the species Charonectria consolationis, writing his life's success into nature's ledger.Footnote 31 Two years later, he was formally appointed full director of the Botanical Garden, a position which he held ‘with honour and self-denial’ (in the words of his friend Augusto Béguinot) until voluntary retirement in November 1915.

From Veneto to the world

A workaholic from childhood to the grave, Saccardo's investigations into fungi deepened and his pace of publication accelerated. The same year as Mycologiae, he issued an excerpt in Nuovo Giornale botanico italiano and encouraged readers to buy his book, the species list serving as a kind of advertisement. He followed, two years later, with three subsequent installments: ‘Series II’ appeared in Nuovo Giornale, the third in German cryptogamic botany journal Hedwigia, and the fourth in the Atti Della Società Veneto-Trentina Di Scienze Naturali (Acts of the Veneto-Trentina Society of Natural Sciences).Footnote 32 The lists appeared without commentary, but their presence in multiple journals suggests both a desire to reach a wider audience and difficulties in doing so. Importantly, however, the last series was published alongside Saccardo's ‘Conspectus generum pyrenomycetum italicorum’ (Overview of the genera of Italian pyrenomycetes), which formally introduced, although with a bare minimum of explanation, the systemate carpologico (‘carpological system’) which he had been broadening since Mycologiae. Opening with a quote from De Notaris, Saccardo classified pyrenomycetes, a large class of decomposers and parasitic fungi whose name comes from the Greek πυρήν (meaning botanical ‘stone’ or ‘kernel’), based ‘on the form and structure of their spores’.Footnote 33 The ‘Conspectus’ was republished, in an abbreviated form lacking the quote from De Notaris, in Nuovo Giornale the next year.Footnote 34

Collectively, the sudden deluge of work situated Saccardo as a leader in Italian fungal taxonomy and the inheritor of De Notaris's legacy. They also signalled his widening scope: from the fungi of Veneto to the pyrenomycetes of Italy, Saccardo's ambit would continually broaden, even as he released updates to his ‘Fungi Veneti’ on a roughly yearly basis. In 1877, evidencing a multifaceted approach and his sweeping aims, Saccardo launched two new publications: Michelia, a journal named for Pier Antonio Micheli, who pioneered the study of fungal spores and the microscopic analysis of fungi, in which Saccardo planned to share ‘diagnoses, observations, lists and other things about Italian fungi’, and Fungi Italici: Autographice Delineati, a collection of coloured drawings that he began during his early research into Venetian fungi, now enlarged to cover the entire country.Footnote 35

In expanding his research horizon, Saccardo was also building his own independent fungal media infrastructure, reliant no longer on foreign journals. He was both editor of and main contributor to Michelia, where he not only described his own collected species, but commented on those from others as well: further lists of ‘Fungi Veneti’ appeared, but also entries such as ‘New fungi from the Herbaria of Gillet, Morthier and Winter’ or ‘New fungi from the Herbarium of Prof. Magnus’; the latter, samples from German botanist Paul Wilhelm Magnus, had been collected across Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. Although ostensibly about Italian fungi, Michelia had gone continental.

The publication's small but meaningful niche earned it subscribers, yet many working botanists of the day would have struggled to see the need. Generalist botanical publications had long existed, and quite a few remained sceptical of specifically cryptogamic journals. Hedwigia, one of the earliest, began publishing in 1852, and United Kingdom mycologist Mordecai Cubitt Cooke's Grevillea, the first English-language cryptogamic journal, started in 1872. Grevillea and Michelia, the former obviously a model for the latter, were both named for early mycologically focused botanists (Robert Kaye Greville and Micheli respectively), and both emphasized fungi, although they were intended to cover all cryptogams. Collectively, the three journals revealed a network of individuals who understood their work as part of a broader project that could be called ‘mycology’, and cleared a path for the eventual arrival of dedicated mycological journals.

The first, the Revue mycologique, was introduced in 1879 and published in Toulouse, Paris and Berlin. Editor Casimir Roumeguère explained that his goal was ‘the dissemination of mycological science’, guiding amateurs into its world and offering experts a place to share their discoveries. The American Journal of Mycology, published in Manhattan, Kansas, followed in 1885 with similar goals. The Transactions of the British Mycological Society began printing in 1896.Footnote 36 Structured as periodicals, Michelia and its ilk were evidence, simultaneously, of the accelerating pace of fungal identification, which could no longer be adequately surveyed by infrequent monographs, and of a growing universe of amateur and expert mycologists, many of whom desired to produce their own publications.Footnote 37

On a personal level, Michelia served as a proof of concept, to Saccardo, for an even larger project, one he would eventually call the Sylloge Fungorum: a comprehensive overview of the world's fungi, classified within his sporological framework and available around the world. (Publication of Michelia would cease in 1882, the year the first volume of the Sylloge appeared.) Modestly, Saccardo publicly hoped only that Michelia and Fungi Italici would someday receive the support ‘kindly granted’ to his Mycologiae. Those expectations were met, and Saccardo's influence on mycology grew quickly from 1879 onwards. From humble Venetian origins to global prominence, he would earn recognition as the court of appeal in fungal science.

Mycological multilingualism and scientific babel

One might have expected the next great fungal systematist after Fries to work in the United Kingdom, France, Sweden or Germany, nations with long mycological research traditions and powerful imperial networks of specimen exchange, or in the United States, where mycology gained prominence toward the end of nineteenth century. Instead, as the Revue mycologique summarized in 1880, it was an author from ‘laborious Italy’ who would produce the first modern compendium of fungi.Footnote 38 Why had this ‘honourable burden’ fallen on the shoulders of an unassuming, if unquestionably enterprising, botanist from Padua? An initial answer concerns the geography of the languages of science.

One of Saccardo's essential skills was the capacity to work in five tongues: Italian, French and Latin (at high levels of fluency), and, secondarily, German and English. Italian allowed Saccardo to engage cryptogamic writing from his own country, ones partially inaccessible to (or ignored by) many, even considering the significant contributions of Italy's cryptogamists, because Italian fluency was limited among the world's scientific community by the second half of the nineteenth century. In the Mycologiae, Saccardo emphasized, characteristically, that the field owed its scientific progress ‘to illustrious Italians’ – not least Carlo Vittadini, who had developed early techniques for culturing microfungi.Footnote 39 That many did not speak the language did not mean that they were uninterested in Italian research, however: in 1878, the Società Crittogamologica Italiana had ‘corresponding’ members from Britain, Germany, the Netherlands and more, many of whom later received Michelia. Americans, however, were notably absent. Giovanni Passerini, director of the Botanical Garden of Parma, and Carlo Luigi Spegazzini, a member of the Società, were also founding collaborators on Roumeguère's Revue mycologique.

If Italian allowed Saccardo local access, then French offered the opposite: as Michael Gordin has shown, French was a vital ‘vehicular language’ for scientists across Western Europe as well as North America.Footnote 40 Few foreigners with whom Saccardo corresponded appeared to write in Italian, but many could do so reasonably well in French. Thus, in 1878, Saccardo began a productive, multi-decade correspondence with Harvard botanist William Gilson Farlow, exchanges of publications and samples between two men almost equally committed to mycological bibliography. Farlow's Harvard predecessor, Asa Gray, had visited Padua, and Saccardo wrote to him occasionally in French as well.Footnote 41 French sustained Saccardo's correspondence with Roumeguère and others in France, as well as important British researchers, many connected to the gardens at Kew.Footnote 42 Much of this French correspondence was dedicated to mailed species identification and had an undeniable systematicity: notes, typically penned on small postcards, often begin with ‘J'ai examiné’ (‘I have examined …’) and continue toward an exclamation that the writer has sent a sample that is ‘tout à fait nouveau’ (‘completely new’).Footnote 43 He was no Proust, but French gave Saccardo an important communicative entrée.

Latin was also critical to Saccardo's project, but for different reasons. He knew it well, from an early Catholic education as well as university studies, and was able to write with ease. From his earliest publications, such as the Mycologiae, to more expansive later writings, such as the Sylloge, Saccardo made the explicit choice to publish names and descriptions in Latin, rather than Italian, to obviate local linguistic particularities. Latin, he felt, was a ‘universal’ language. As Gordin shows, the choice went against trends in the international scientific community: Latin's universality was already losing steam in 1850, not to mention thirty years later.Footnote 44 But this was less true in botany. ‘Those who wish to remain ignorant of the Latin language, have no business with the study of Botany’, wrote naturalist John Berkenhout toward the end of the eighteenth century, and Latin competency remained a sine qua non well into the nineteenth.Footnote 45 Botany, indeed, was a rare discipline where Latin's hold grew stronger as the nineteenth century came to a halting close: in 1906, European botanists agreed to formalize the requirement that new species be named and described in Latin, a decision Saccardo supported.Footnote 46

He was ahead of that curve, then, but writing exclusively in Latin remained only one of many possibilities. Saccardo's introduction to Mycologiae Venetae, for instance, was in Italian, and many publications from his international colleagues appeared in English, French or German, as suited their national origins, often limiting themselves to those national origins (Fungi of Britain, Fungi of North America). Scattered notes also suggest that Saccardo's insistence on Latin went against popular practice elsewhere: American botanist William Trelease wrote, of a collaborative identification of the fungi of Alaska (the first ever), that ‘Professor Saccardo's diagnoses are published in Latin, as written, in order that shades of meaning might not be lost in the process of translation, and for uniformity the explanation of his plates is given in the same language’.Footnote 47 Americans were, in other words, willing to entertain Saccardo's Latin predilections, although not entirely accustomed to them.

As Trelease noted, Latin was meant to thwart the loss of meaning in translation. But it also tied the Sylloge and Saccardo's other writings, however implicitly, to the work and vaulted image of his systematic predecessors. The most proximate was Elias Fries, the Swedish botanist whose Systema Mycologicum, written in Latin, represented the clearest antecedent to Saccardo's project. More prominent, however, was Linnaeus himself, responsible for constructing the binomial nomenclature that cemented the importance of botanical Latin.Footnote 48 Despite Linnaeus's own minimal knowledge of the fungi, Saccardo considered his work foundational, and argued, in 1909, that cryptogamic nomenclature should be regarded as starting in 1753, the year of publication for Linnaeus's Species Plantarum, rather than the later dates of appearance for Fries's Systema or Christiaan Hendrik Persoon's Synopsis methodica Fungorum – a suggestion only adopted finally in the 1980s.Footnote 49 The Sylloge Fungorum's internal Latin positioned the work as universal and Saccardo as the inheritor of a project of Friesian and Linnaean importance.

Saccardo's capabilities in English and German are less certain from the archival record. He collaborated with botanist Giovanni Canestrini in translating Charles Darwin's Insectivorous Plants (1875), published as Le piante insettivore in 1878, which suggests a minimal working familiarity, but he almost never wrote in it. The enterprising American mycologist Curtis Gates Lloyd sent him letters in English (Saccardo responded in French), as did Cooke (who apologized for not knowing Italian), but an intermediary may have assisted in translating them. Plowright encouraged him to ‘write in Italian’ in 1881, then to ‘write in French’ the next year, suggesting that Saccardo tried to meet his interlocutors where they were linguistically. His German appeared passable, although he also avoided writing in it. Saccardo had worked closely with German-speaking researchers, notably Otto Penzig, who studied with him in Padua and collaborated with him on an analysis of fungi from Java (published, in German, by E.J. Brill). Although Penzig wrote to Saccardo in Italian, others sent letters in German and a handful of Saccardo's publications (still typically penned in Latin) appeared in German-language journals, such as Botanisches Zentralblatt.

This polylingual flexibility, supplemented by local assistants, enabled Saccardo to read and write letters, journal articles and monographs to and from authors in each of the world's major centres of mycology as well as many at the edges of the known mycological universe. That extensive correspondence network, in turn, was essential to his hopes of collecting and, in many cases, personally examining most fungal species known to man. That Saccardo translated all these names and descriptions into Latin – leaving Latin as a kind of compressed, ‘lossless’ format – meant that he was performing a similar role to the one Linnaeus once had. Describing specimens was one thing, however, and even centuries later, the difficulty of moving them across vast distances and oceans remained significant.

Moving mushrooms in the mail

American mycologist Job Bicknell Ellis, who eagerly requested copies of everything Saccardo produced, complained in 1880 that his latest Michelia had still not arrived. He blamed delivery directives from the postmaster of New York: ‘I am very sorry that so small a man should get into so important a place & thus be able to discommode the people by his foolish direction’, Ellis wrote, before requesting that Saccardo send the package again.Footnote 50 Despite logistical difficulties, correspondence between Saccardo and Ellis was supported by a major transformation in the structure of international information exchange: the formalization of the General Postal Union (later the Universal Postal Union) by the Treaty of Bern in 1874. The resulting International Postal Service, founded on the principal that all of the world was, postally, one territory, established a system of uniform rates and measurements which eased private correspondence and eliminated a palimpsest of contradictory government policies for incoming and outgoing mail. The system eventually worked ‘with such smoothness and on so extensive a scale’, F.H. Williamson, the United Kingdom's director of postal services of the General Post Office, could note in 1930, ‘that probably few of those who habitually use it have ever given a thought to the extremely complicated machinery and the comprehensive and detailed organisation which is necessary to ensure this desirable result’.Footnote 51 It was a tremendous boon for scientists such as Saccardo. Up to the mid-1870s, for instance, Saccardo routed many of his United Kingdom packages through Cooke, so that fungal specimens to or from frequent correspondents such as Plowright went to Cooke first.Footnote 52 But by the 1880s and 1890s, writers could get packages and mail orders directly to Saccardo, which meant that texts, fungal specimens and species identifications could move, at least in principle, far more rapidly.Footnote 53

As payment for his writings, many correspondents sent Saccardo money – francs, rather than pounds or dollars, which became the primary currency of South and Central Europe following the Latin Monetary Union.Footnote 54 They often did so, however, for below the cost of publication. To make up the difference, correspondents typically included copies of their own work as well as samples for Saccardo to add to his collections. Charles Bagge Plowright, for example, a British physician and mycologist, sent specimens from his Sphaeriacei Britannici, a collection of fungal ‘exsiccatae’, and was ‘very pleased’ to learn that Saccardo was ‘willing to exchange fungi’.Footnote 55 Exsiccatae, prepared collections of dried specimens often issued in journal-like ‘centuries’ of one hundred specimens, were vital elements of international exchange at a moment when living fungi were almost impossible to send by mail.Footnote 56 Ellis, too, forwarded centuries of his North American Fungi along with a nearly continuous stream of additional specimens: ‘I would be glad to exchange some new or rare American species for specs. of new or rare Italian fungi’, he wrote in June 1880.Footnote 57 Exsiccatae had an additional utility, because Ellis and others could hide subscription payments with fungal samples to avoid the former's loss or theft during lengthy postal journeys.Footnote 58

Within Saccardo's network, books, exsiccatae, individual collections and francs operated as semi-interchangeable denominations of a single currency. In 1877 Plowright wondered whether Saccardo would rather have century two of his Sphaeriacei Britannici or a hundred specimens of ‘all kinds of British fungi: not the very commonest species’. In general, the critical matter was that of ‘even’ exchange, rather than individual profit. In 1883, Ellis sent Saccardo a detailed accounting of exchanged materials (journals, books and exsiccatae) which he claimed showed a 44.25 franc ‘bal[ance] in my favor’.Footnote 59 The straightforwardness of these equivalences is at times surprising, but difficult-to-access specimens were as good as gold, since money was needed to pay someone to acquire them, and books written with first-hand experience held information that Saccardo dearly needed to expand his database. Exchanges also obviated the need for extensive travel, which was expensive and which Saccardo generally avoided, while simultaneously allowing a degree of imaginative exploration for participants. ‘There really are some wonderful fungi in Italy’, Plowright declared, after receiving the most recent copies of Saccardo's Fungi Italici.Footnote 60

Much of this correspondence took place with men whom Saccardo had never met or had encountered only briefly. ‘I shall probably never meet you or any of my Italien Science-friends personally’, wrote the Australian German botanist Ferdinand von Mueller in 1893 after an exchange of article prints.Footnote 61 This distance generated challenges of both trust and imagination. Responding to a photograph forwarded by Saccardo in 1902, Lloyd was ‘surprised to see you such a young looking man as I had formed the impression in some way that you were elderly’.Footnote 62 Photographic portraits, sent back and forth across long distances, enabled a partial bridging of geographic divides, putting face to virtually witnessed name: Lloyd loved to publish up-to-date photographs of mycologists in his journal issues, and Saccardo proactively maintained an exhaustive ‘Iconotheca’ of botanical portraits in Padua.Footnote 63 It seemed easier to trust another botanist's species identifications if one had an idea of what kind of man he was, especially what he looked like. But such indirect contact also occasionally irritated intermediaries. The Roman Catholic priest and botanist Benedetto Scortechini, who scoured Malaysia for specimens on behalf of the Royal Botanic Garden Calcutta, sent samples back to Kew with the hope that they would be transferred to Saccardo. ‘Something ought to be done’, fumed Kew director William Turner Thiselton-Dyer, so the Crown's botanists would no longer be serving as agents in a Scortechini–Saccardo exchange.Footnote 64

For most who sent and received samples, the mailed specimens served as a way of signalling intimacy and respect. ‘I think you Italians have a proverb about “Knowing a man only after you have taken money from him” and I am afraid you will say you know me when you have taken fungi of me!’ exclaimed Plowright, before begging Saccardo not to send further materials until he had assembled the specimens he owed.Footnote 65 ‘Have you not had enough of my exchanges to disgust you?’ he wondered the next year.Footnote 66 Saccardo had not, and tended to show his appreciation by liberally naming new species after those who sent them to him: Plowright's name was attached to a genus of woody plant associates, Ellis's to a specimen Saccardo called Ellisiella candata, Farlow's to still others.Footnote 67 In 1910, Harvard's Roland Thaxter wrote asking for a ‘small bit’ of the genus Thaxteria so that he might ‘know what I look like under the microscope’.Footnote 68 Naming species for friends also cemented Saccardo's place as a key node in fungal identification: ‘Dr Cooke discourages the collectors by his extreme aversion in linking their names with something new in naming. Who would hold this desire of ambition against anyone?’ von Mueller wrote to Saccardo in 1891.Footnote 69 Cooke did not refuse Saccardo, however, naming the Saccardia family of sac fungi after him.

Members of Saccardo's network repaid the favour by spreading his identifications and helping to build a subscriber base for the Sylloge Fungorum years before its first volume was released. Constructing an adequate subscription list was make-or-break for early scientific publications, so Saccardo began informing contacts in April and May 1880 of his intentions to start a wide-ranging project. Ellis quickly confirmed that he would subscribe and circulated the project prospectus among friends.Footnote 70 One month later, he was pleased to inform Saccardo that he had found a subscriber: Pennsylvania physician George Martin.Footnote 71 Plowright, who had previously suggested that Saccardo undertake a more extensive project on the pyrenomycetes – exactly where Sylloge Fungorum begins – promised to buy the text and encouraged him to include ‘a very complete index’. Such an index was critical, he explained, especially for the ‘poor English and Americans’ who do not ‘have every new genus at [their] fingers’ end’, like their Italian and German colleagues.

Continental Europeans, however, were just as excited: the Sylloge responded to a need ‘too well known for us to insist much on its importance’, explained a note in Revue mycologique in 1880, with readers encouraged to quickly send in purchase forms. Roumeguère was an ardent supporter of the project, and Saccardo himself emphasized its urgency in a subsequent issue of the Revue: there were at least fifteen thousand species with descriptions scattered in ‘hundreds of academic Acts, botanic journals and brochures’ that were ‘very difficult to find’, he noted.Footnote 72 Sweden's Botaniska Notiser echoed those sentiments, praising the project in light of mycology's fragmented state.Footnote 73

Producing the book was made possible by Saccardo's impressive library of both specimens and publications, and the Sylloge fittingly begins not with the promised list of fungal species, but with a ‘Mycological bibliography’. The Sylloge was thus doubly useful, a proto-database both of species and sources (see Figure 2). For these reasons, publication was anticipated even beyond the narrow corridors of the mycological community: ‘The first part of Professor Saccardo's Sylloge Fungorum Omnium is now in the press, and will soon be ready. It will be the most exhaustive treatise on mycology of the day’, explained the science section of Australia's Adelaide Observer.Footnote 74

The microscope and the question of systems

Predictably, the Sylloge's first volume, released in July 1882, travelled extensively. A review in Hedwigia regretted an inability to engage it in detail but praised Saccardo's astonishing diligence and accuracy.Footnote 75 Roumeguère's review was delayed because Revue mycologique also published in July, but he spared no adulation in October: the fifty years since Fries's compendium had seen a ‘revolution’ in mycology, thanks to advances in microscope technology, and Saccardo's book evidenced ‘a completely new science’.Footnote 76

Those technical improvements, although unspecified, were vital. Early microscopists, such as Robert Hooke, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek and Marcello Malpighi had identified a number of fungi, but quantitative analyses of smaller species advanced little through the mid-nineteenth century. As Lea Beiermann has recently argued, however, microscopy transformed dramatically in the mid-century, propelled by a growing international trade in microscopes for experts and amateurs and the emergence of widespread societies and clubs to teach microscope technique across significant distances.Footnote 77 Many in Italy's cryptogamic botany community were thus also members of the Dublin Microscopical Club, the Royal Microscopical Society in London, or the Belgian Society of Microscopy.Footnote 78 This social and commercial shift occurred alongside more technical efforts to fix spherical and chromatic aberrations in microscope objectives by the Chevalier brothers of France, Joseph Lister in Britain and Giovanni Battista Amici in Italy.Footnote 79

The major microscopical advances of the late nineteenth century are often associated with bacteriologist Robert Koch and the oil immersion objectives and substage condensers of the Zeiss factory at Jena which produced a higher image resolution and enabled photomicrographs of bacteria.Footnote 80 But members of the international mycological community of the mid-nineteenth century were avidly interested in microscopes before Zeiss models became widespread: Roumeguère dedicated whole sections of his books and early volumes of Revue mycologique to their use, the difference in microscope types and approaches to specimen preparation. He recommended guides (Henri van Heurck's Le microscope was a favorite) and specimens for those too impatient to prepare any themselves, including a series sold by James Edward Vize, the vicar and curate of Forden Church in Welshpool, England.Footnote 81 Saccardo was himself interested not only in microscope usage, but also in the device's history, publishing an extensive examination of claims to the instrument's discovery with a careful analysis of primary-source letters and documents.Footnote 82 Important as microscopes were for bacteriology, they expanded the visible and reproducible universe for mycologists, especially for the microfungi. Saccardo's work partially charted the extent of that expansion.

Not everyone was so uniformly positive about the Sylloge, however. Cooke, Saccardo's long-time correspondent, reviewed it in Trimen's Journal of Botany in 1882 and again in Grevillea.Footnote 83 Acknowledging its ‘Herculean task’, he critiqued the ‘carpological’ arrangement for being inconsistently applied and, more damningly, a return to the ‘Artificial System’ of Linnaean works, rather than the ‘Natural System’ adopted by Fries and others.Footnote 84 Cooke, who was known for stringent attacks on scientific contemporaries, ones which caused a complete falling out with Ellis, may also have felt a bit of comradely jealousy.Footnote 85 He had started a similar series back in 1875, Mycographia, in which he planned to list and illustrate all known fungi, but the project had faltered. He had also struggled at times to ensure that international scholars sent samples to him rather than to Saccardo.Footnote 86 Nevertheless, Cooke refused to let his disagreements get in the way of aiding Saccardo. As he insisted following the publication of the Sylloge, ‘I do not permit any difference in opinion to interfere with my desire to render you any assistance in my power. I cannot agree with you, but am as willing as ever, to help you as far as I can.’Footnote 87

Concern over whether Saccardo's ‘artificial’ spore-based system actually represented an improvement on ‘natural’ systems of classification, arranged for instance by evolutionary relationships among fungi, was in fact widely shared. Saccardo divided fungi by the characteristics of their spores and spore-bearing structures – size, colour, shape and so on – which occasionally separated species which are related by present standards into different genera. The challenge was that tracking these evolutionary connections was exceptionally thorny: neither fungal culture collections nor morphological studies of younger specimens were well developed. Therefore, as a flood of volumes followed the first Sylloge, concerns about Saccardo's approach were outweighed by the undeniable value of the project and the ease of applying his classifications in practice. Plowright noted Cooke's criticism in 1882, but insisted that there was ‘no mistaking the fact that it is possible now to make out a Sphaeria [from] your Carpological arrangement: whereas it was not possible to do so before’.Footnote 88 Saccardo had even produced a kind of companion guide in 1891, Chromotaxia, which helped authors translate hues from English, German, French and Italian into fifty standard Latin colours to correctly name and identify species.Footnote 89

His singular willingness to keep offering new volumes of the Sylloge blunted deeper criticisms of its specifics. Many had wanted to produce something similar to the book, even to improve on it, but Saccardo had actually done it. The effect was undeniable: in 1966, mycologist Emory Simmons noted in the Quarterly Review of Biology that Saccardo's system remained the preponderant framework for taxonomic mycology, even as it presented concatenating dilemmas for researchers.Footnote 90 Many of Saccardo's terms, such as ‘staurosporous’ and ‘helicosporous’, which differentiate fungal spores into those which are star-shaped or spiral-shaped (among other possibilities), are also still in use today.Footnote 91

The Sylloge made a smaller initial splash in America than in Europe. Ellis published announcements about Volume 1 in the American Naturalist, and Farlow highlighted the book in the Smithsonian's annual report, but few notable reviews appeared. Saccardo's renown across the Atlantic soon swelled, however. After the eighth and final of the originally planned volumes appeared in 1889, University of Nebraska botanist Charles Edwin Bessey could only echo others on the sublime nature of Saccardo's accomplishment: ‘The completion of so great a labor in so brief a space of time must excite at once our wonder and admiration.’ Whatever one felt about its organization, Bessey added, there was a comfort in seeing such an undertaking planned and carried out within a single generation – separating Saccardo's volumes from ‘the depressing influence’ of De Candolle's well-known works on phanerogams, which dragged on for fifty years after the first volume's completion. Bessey hoped that Saccardo's book might even encourage others ‘to see great undertakings inaugurated’.Footnote 92

How many were directly influenced to do so is uncertain, but one obvious example was Giovanni Battista de Toni's Sylloge Algarum (1889–1924). De Toni studied at Padua, and his book's title, printing and style mirrored the Sylloge Fungorum's, on which de Toni had assisted. Later influential publishing undertakings, such as Gustav Lindau and Paul Sydow's Thesaurus litteraturae mycologicae et lichenologicae or Alexander Zahlbruckner's Catalogus lichenum universalis revealed Saccardo's influence as well. At the same time, the pace of international mycological publication was accelerating everywhere, with new periodicals, including Curtis Gates Lloyd's Mycological Notes (1898–1904), sprouting up to vet the mountain of findings.Footnote 93 Saccardo's books were invaluable as a uniform reference, and his consistently applied framework offered a solution for those whose growing mycological collections needed organizing. An 1891 report of B.T. Galloway, chief of the United States Department of Agriculture's Division of Vegetable Pathology, thus noted that the division's herbarium was to be organized, at the genera level, ‘according to Saccardo's Sylloge Fungorum’.Footnote 94 At a general level, too, Saccardo and his network of collaborators had shown how stunning the diversity of the world's fungi really was.

Despite its unifying intentions, however, the Sylloge's swarm of species and attributions also supported what Lloyd called ‘species-making’: the tendency to name new species for reasons of personal renown more than careful science. Such was ‘the curse of mycology since the beginning’, one to which the ‘appearance of Saccardo has been a great boon’. Yet resistance to species-making was no better than tilting at windmills, because most researchers had ‘more or less a touch of the fever’ – Lloyd admitted he was hardly immune himself.Footnote 95 Numbers of identified fungi were skyrocketing, and the project Saccardo had originally planned to finish in four years continued four and then twenty more. By the fourteenth volume, in 1899, there were 47,304 identified species of fungi, a number which grew to 58,015 only four years later. Lloyd had every expectation that it would continue: ‘Who knows them all? … Or who could ever be able to learn one-tenth part of them in a life-time? The subject of mycology is too large for any one man to master now in detail’.Footnote 96

Only Saccardo came close to that level of mastery, although he assiduously avoided claiming it for himself. Nor was keeping pace easy, and the Sylloge's editorial staff ballooned over time as Saccardo was forced to take on assistants and quit his formal duties at the Botanical Garden in order to adequately devote himself to subsequent volumes. Even this total commitment, however, was no match for a coming catastrophe, one few on the Continent anticipated: the First World War, ‘la Prima Guerra Mondiale’, which came to Italy in 1915.

The twenty-second volume of the Sylloge Fungorum, co-produced with Saccardo's son-in-law Alessandro Trotter, was published on 20 August 1913. As the front line approached Padua, Saccardo wrote to Farlow in May 1917 to inform him that Volumes 23 and 24 were nearly complete and to inquire whether the Carnegie Institution might provide a thousand dollars for a publishing subvention. Farlow, who frequently seemed short on funding but tried to help others where he could, responded in July that Harvard could likely support part of the request. His letter, however, was delayed until August. Fighting soon pushed Saccardo from Padua, and the reach of Farlow's pen, but he continued to hope for the promised funding. Gates, informed of the news in 1918, encouraged him to delay publishing in ‘these troubled war times’, but his advice was unnecessary.Footnote 97 Farlow passed away in June 1919 before any of the money could be sent, and Saccardo died the following February. After a seven-year delay, the twenty-third volume, under Trotter's name, appeared in 1925.

Conclusion: omnium hucusque cognitorum and database histories

Saccardo was arguably the last individual to know most of what one could about fungi – a mycological Leibniz of sorts. But he did not know all fungi, and he knew many only thanks to an extensive network of correspondents who helped him identify, collect and compare samples. Lloyd, who thought there would be 30,000 fungal species ‘if all were correctly known’, was perhaps right to revile species-making (later researchers would find countless examples of duplicate or incorrect identifications), yet the number of identified fungi never stopped growing. Today, there are nearly 150,000 described species, exactly the number Saccardo once imagined to be the world's total.Footnote 98 With advances in methods of collection and analysis, contemporary estimates of fungal diversity edge ever higher, with predictions ranging from two, three and five million to ten or twenty million species.Footnote 99 As mycologist and historian Geoffrey Clough Ainsworth bluntly stated in 1968, the question ‘How many fungi are there?’ could be answered in two words: ‘Nobody knows’.Footnote 100

Saccardo knew and identified, then, only a fraction of the world's mycological diversity. Like many accomplishments, his was unevenly distributed and susceptible to breakdown. Already in 1890, during a period of widespread generalist interest in fungi, the Sylloge was appearing in rare-book auctions in London and New York.Footnote 101 Cornelius Shear, of the United States Department of Agriculture, asked Saccardo in 1905 whether he had, or knew of where one could acquire, additional copies of ‘Vols. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, or 8’, while Washington, DC's Carnegie Museum was celebrated in 1906 for securing a set that was ‘exceedingly difficult to get’ now that ‘all the ancient volumes are quite out of print’.Footnote 102 Daniel McAlpine, the first plant pathologist of Victoria, Australia, began his own systematic exploration of Australian fungi in part due to the ‘inaccessible’ status of works such as Saccardo's.Footnote 103

Among the most unexpected attempts to make Saccardo more accessible came decades later. In March 1943, as General George Patton led American tanks into Tunisia, the United States Alien Property Custodian Leo Crowley announced that four hundred technical and scientific texts originating in the Axis countries, especially Nazi Germany, were now available for American publishers to reprint freely. Aimed particularly at knowledge that was ‘most essential in the war effort’, including ‘volumes on aviation, medicine, gas warfare, oceanography, physics, chemistry and other technical subjects’, the oldest book included in the programme was none other than Saccardo's Sylloge Fungorum, which retailed for two hundred dollars (nearly three thousand dollars today, but a tenth of its previous price).Footnote 104 When the United States Bureau of Plant Industry's John Stevenson announced plans to reprint it later in 1943, he called Saccardo's Sylloge the sine qua non of mycology. Even those who already possessed copies, Stevenson mused, might want a new set to ‘relieve the wear and tear on the original’.Footnote 105

Despite its inaccessibility, Saccardo's enormous undertaking, both by the standards of the day and still to the present, was crucial in drawing regionally and nationally based fungal analyses together for the first time into a single text with a common language and classification system. As an early database both of species names and of the world's bibliography of mycological writing, Saccardo's work charted a path connecting the older natural-history tradition and the burgeoning experimental one: new generations of phytopathologists, taxonomists and medical mycologists could all draw on Saccardo's system, even if they asked different questions for diverse reasons. The book was good to work with, and shaped practice for many decades.

If ‘database’ is an anachronism that Saccardo himself would not have recognized, his ‘sylloge’ of data nevertheless represented a globalizing development on the taxonomic list as a research technology. Müller-Wille and Charmantier have argued that lists such as these reduced information overload by containing data within manageable systems and categories, while occasionally contributing to the challenge itself: Saccardo's possible encouragement of ‘species-making’ offers one example.Footnote 106 But working with lists could itself be generative. University of Minnesota botanist Frederic Edward Clements, for instance, translated the taxonomic keys in the Sylloge's first eight volumes for use in teaching students whose Latin fell short of Saccardo's, then proceeded to publish a full translation with Cornelius Shear (The Genera of Fungi, 1909), which enabled a wider English-speaking audience to adopt Saccardo's system and Clements to test his own classificatory ideas.Footnote 107

Contemporary mycological researchers have not failed to see in Saccardo's and Fries's undertakings predecessors or precedents for the modern digital fungal databases that structure their work.Footnote 108 ‘Index Fungorum’, the central global nomenclatural database, still frequently links first to pages of the Sylloge. Facing down a flood of newly identified fungi, Saccardo reveals how collecting and classifying in mycology became, more explicitly, a ‘big-data’ information management project, and the account offered here enables scholars to connect developments in mycology and botany to other globalizing information practices of the turn of the century, foundations for present-day questions about what big data means for the life sciences. Contemporary policies around fungal conservation and debates over the total number of fungi also rely on these data practices: what we cannot know or see, we struggle to save. In painstakingly producing the Sylloge, Saccardo established a foundation upon which later scholars could build, or from which they could depart, as they often did. From Padua, Saccardo and his broad network helped to globalize mycology, a project that is still very much under way.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my reviewers for their thoughtful feedback on the paper, to Amanda Rees and Trish Hatton for their guidance, and to Michael Rossi for comments on an early draft. Donald Pfister, who taught my first mycology course years ago, has been an invaluable resource. I thank Sophia Roosth for advice on a few questions and Arthur Lucas for early access to the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria collection of Ferdinand von Mueller documents. My research assistant Marina Takara assisted in identifying Japanese materials. Finally, the paper benefited from engagement by attendees of the Mycology and Its Discontents: Fungi and Category Confusion panel at HSS 2022, including undergraduate students of my course, ‘How to Stop Worrying and Learn to Plan and Write a Book (about Fungi)’.