INTRODUCTION

In 2021, Ali Fazeli Monfared was beheaded by his relatives upon their discovery of his sexual orientation. In Iran, homosexuality is a ground on which to be exempted from compulsory military service, and Ali had disclosed his sexual orientation to officials accordingly. After finding the exemption card that revealed Ali’s sexual orientation, a group of relatives killed him in the name of preserving the family’s “honor” (Yurcaba Reference Yurcaba2021). At first blush, this homicide appears to be independent of the state; indeed, it was commissioned by private actors and in the absence of formal state authority. However, a closer examination reveals the inextricable complicity of the state in this act of gross violence.Footnote 1 As we will explore, Iran is one of twenty-three states that have curated societies in which same-sex attraction is viewed as deviant and death worthy, thus enabling such violence (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 19).

This article provides a critical legal pluralist account of global practices of state-enabled killing of people who are, or are perceived to be, same-sex attracted. “State-enabled killing,” as we use this term, includes the death penalty, extrajudicial killing, lawful excuses to homicide, and “conversion therapies” that lead to death. We argue that the lens of critical legal pluralism reveals a functional equivalence among all these forms of state-enabled killing, the normative implication of which is that they must all be at the forefront of reform efforts. We will start, in the first few sections, by clarifying the scope of the study and the concepts used as well as by justifying our methodological approach. We will then turn to a substantive analysis of capital punishment for same-sex sexual activity, different instances of extrajudicial and quasi-judicial killing of same-sex-attracted people as well as state-enabled killing of same-sex-attracted individuals carried out by private actors. This will in some cases involve discussions of violence against same-sex-attracted people, but only insofar as it is relevant either to illustrating those instances of state-enabled killing that result from the lethal consequences of violence or to providing context to other case studies of state-enabled killing that we cover. An analysis of the broader problem of (state-enabled) nonlethal homophobic violence is beyond the scope of this article.

For reasons of linguistic economy, we use the phrase “same-sex-attracted people,” but a qualification to this terminological choice is in order. It is plausible to assume that people who are in fact same-sex attracted are those that the legal provisions we analyze were intended to target and against whom these provisions are primarily used. But it should be borne in mind that people who happen not to be same-sex attracted may also become victims of the forms of state-enabled killing we analyze for at least three reasons. First, wrongful convictions, in which genuine mistakes are made, are possible in the enforcement of relevant legal provisions. Second, deliberate misuse of such provisions on the part of the authorities is also possible. Indeed, sodomy offences have a long history of being misused for political purposes or to suppress dissent. In Medieval Europe, for example, the offence of sodomy was scarcely distinguishable from the offence of heresy (Goodrich Reference Goodrich1976). Third, transgender people who are not same-sex attracted (such as a trans woman attracted to men) may be perceived as same-sex attracted because of a collective failure to acknowledge their sex/gender identity, and their sexual activity may accordingly be classified as same-sex sexual activity for law enforcement purposes. The provisions that we discuss may also have a disproportionate impact on gender nonconforming queers who are likely to become a prime target of homophobic law enforcement because they cannot, or refuse to, pass as heterosexual.

CRITICAL LEGAL PLURALISM AND ITS USES

Legal homophobia (dread of same-sex-attracted people) (Weinberg Reference Weinberg1972, 4) and/or heteronormativity (treating heterosexual relations as primary and foundational to the social order) (Warner Reference Warner1993, xxi) can take myriad different forms. These include, among others, the criminalization of consensual same-sex sexual activity;Footnote 2 the censorship of gay-affirmative expression (whether or not sexually explicit);Footnote 3 the disqualification of same-sex-attracted people from certain roles (spouse,Footnote 4 parentFootnote 5 ) or institutions (the military, for instance)Footnote 6 that are deemed important to society; the failure to adequately provide for protection from discriminationFootnote 7 or homophobic hate;Footnote 8 and the judiciary’s failure to resolve conflicts of rights in favor of same-sex-attracted people when the law permits it and political morality requires it (Nehushtan and Coyle Reference Nehushtan and Coyle2018). It is arguable that any of these manifestations of legal homophobia and/or heteronormativity could contribute, indirectly, to a climate that makes homicidal violence against same-sex-attracted people more thinkable and their demise—to borrow from Judith Butler (Reference Butler2016)—less “grievable.”

There are, however, ways in which legal homophobia/heteronormativity play a much more direct role in causing the death of same-sex-attracted people. We have termed these instances “state-enabled killing,” and they are the focus of our analysis. Prime among them is the imposition and enforcement of the death penalty on people found guilty of engaging in same-sex sexual activity. But it would be a mistake to treat the death penalty as the only genuine form of state-enabled killing of same-sex-attracted people, as doing so obscures a number of other instances in which the state is directly complicit in the deaths of such persons. Homophobia is manifold, and while anti-gay laws undoubtedly ensue in homicidal violence as a form of legal (or “institutional”) homophobia, states are equally responsible for reinforcing “cultural homophobia” (those social norms that dictate “correct” sexuality and ensue in punishment for noncompliance, leading to honor killings, for example) and for legitimizing “interpersonal homophobia” (violent manifestations of which include acts motivated by so-called “gay panic,” which in many jurisdictions is a lawful defense to homicide).

We have sometimes encountered resistance, particularly outside academia, to the idea of treating such other forms of state-enabled killing on a par with the death penalty.Footnote 9 The methodological framework of critical legal pluralism can help explain why this move is warranted. At a minimum, critical legal pluralism frees up an analytical space to pursue the practical and normative implications of hypothesizing a functional equivalence between the death penalty and other forms of state-enabled killing. Such implications are wide-ranging and potentially life saving—for example, under Australian law, a same-sex-attracted person in fear of honor killing in Jordan may be denied a protection visa if unable to demonstrate an inability to avail themselves of the protection of their home country.Footnote 10 Given that Jordan does not criminalize same-sex intimacy, the fact that honor killing is commissioned by non-state actors may, assuming a monistic conceptualization of law, impede the asylum seeker’s justification of their inability to obtain state protection, thereby precluding their receipt of asylum. On the other hand, by recognizing that such violence is “state-enabled” in the Jordanian context,Footnote 11 a pluralistic approach is cognizant of the asylum seeker’s inability to obtain state protection due to the complicity of the state itself in the violence, thereby assisting their asylum claim.

Though we have just referred to critical legal pluralism as a methodological framework, it is so only in a loose, or contested, sense. Rather than a set of theoretical principles or a well-defined set of analytical procedures, Margaret Davies (Reference Davies2005) argues that critical legal pluralism is best understood as an ethos. Legal pluralism originated as a way of understanding colonial or postcolonial legal systems characterized by the co-existence of more than one legal tradition.Footnote 12 Critical legal pluralism radicalizes this mode of understanding and applies it not only to legal systems but also to the very concept of law (Kleinhans and Macdonald Reference Kleinhans and Macdonald1997; Davies Reference Davies2005). This has two consequences. First, much that would not constitute “law” from a non-pluralist perspective (and, indeed, from a first- or second-generation pluralist perspective) does qualify as “law” for critical legal pluralists (that is, from a third-generation perspective). This move is largely justified by critical legal pluralists on ethical grounds: rather than taking the top-down perspective of the state, critical legal pluralists prefer a phenomenological, bottom-up approach that takes seriously the individual experience of the addressees of primary rules or those who bear the brunt of them (Hart Reference Hart2012, 79). This is the reason why critical legal pluralists speak of “subject-driven” law (Davies Reference Davies2006, 592): every regulatory regime that looms sufficiently large in the life worldFootnote 13 of individuals and communities has a claim to being called “law” or, at any rate, to being treated on a par with official state law and, hence, to becoming the subject matter for legal scholarly inquiry.

The second consequence of critical legal pluralism applying a pluralist mode of understanding to the concept of law is a shift in our understanding of “a clear central case of our concept of law” (Perry Reference Perry1998, 432; emphasis in original)—namely, the legal order of a modern municipal legal system. This does not necessarily mean that critical legal pluralism demotes official state law from being a, or even the, central case of law. After all, if critical legal pluralism is ultimately rooted in phenomenology,Footnote 14 then it needs to reckon with the largely state-centered understandings of law held by many individuals and communities to whom primary rules apply.Footnote 15 Rather, critical legal pluralism shifts our understanding of state law by bringing into focus the internal complexity, incoherence, and multifariousness of state law as a project in tension with itself. These are the very features that doctrinal legal scholars deliberately attempt to eliminate or mitigate in their reconstructions or restatements of specific branches of state-based legal systems.

We think that Davies (Reference Davies2005, 98–99) is onto something when she argues that such preferences for plurality over singularity or vice versa are largely due to one’s aesthetic sensibility. At the same time, Davies recognizes that apologists of pluralism may claim, among other things, that pluralism provides a more accurate representation of reality than its alternative, which suggests that those who practice pluralism may experience their scholarly practice as epistemically necessitated (94). We suggest that, broadly, the preferring of plurality or singularity in one’s account of law is indeed a matter of epistemic necessity but in the sense that it generally is (or at least should be) dictated by the goals of one’s inquiry into law. If one’s aim is to yield an empirically accurate depiction of currently extant state law, a pluralist approach will tend to have the edge over one focused on coherence and singularity. State law is the product of not always particularly well-coordinated activities of differently situated human agents, who are actuated by disparate aims and are cognitively limited. As a matter of empirical truth, such a product cannot result in an internally coherent, unified system of rules.

If, however, one’s aim is—as it is for doctrinal scholars—to generate a restatement of the law that irons out tensions and inconsistencies in order to make the law easier to interpret and apply by those whose task it is to do so (lawyers, judges, public officials, students asked to answer problem questions), then it makes absolute sense to emphasize singularity and coherence in one’s account of law. In particular, such preoccupations with consistency will be at the forefront in the minds of judges, who are well aware that integrity is a distinct virtue of legal systems, being conducive to the rule of law (Dworkin Reference Dworkin1986). Legal and political philosophers may also have good reason to put the emphasis on coherence: it enables them to show how certain postulated political, law-making, and law-applying arrangements fit together and are able to generate, under certain conditions, the kinds of outcomes political and legal philosophers rightly care about (fairness, efficiency, due process, and so on).

In this article, however, we are not writing as legal philosophers, judges deciding cases, or doctrinal scholars. Rather, we are aiming to provide a fairly comprehensive and descriptively accurate account of the ways in which state law provides for the deaths of same-sex-attracted people, and we argue that the death penalty is only the most egregious example of this account. It seems to us that our subject matter is therefore a prime candidate for the kind of treatment facilitated by critical legal pluralism: to same-sex-attracted persons, the different ways in which state law can impart death upon them are likely to appear as functionally equivalent. Our account, then, is pluralist for the two very reasons we have argued tend to vindicate the adoption of a critical pluralist perspective: the ethical demand to adopt the perspective of those who bear the brunt of the relevant law and the epistemic demand to provide an account that is sensitive to the empirical fact of the ineradicable plurality of state law.

METHODOLOGY

Examining the period between 2015 and 2020, this study is based on a review of publicly available sources and interviews with experts in the field. Our literature review extended beyond academic literature to include governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGO) reports, media articles, and online execution databases, and, where necessary, we contacted the authors of these sources to verify the accuracy or reliability of findings. Where gaps in the literature were identified, we conducted semi-structured interviews with field experts (rights activists and organizations, lawyers, and scholars) to enhance our understanding. Interviews were conducted remotely (via Skype and Zoom) between January 2020 and February 2021. Of the fifty-eight individuals and organizations that we approached, seventeen were willing to speak with us (see the Appendix for a list of the interviewees). The overwhelming reluctance of many to participate in our research demonstrates the potential risks of speaking up against the persecution of sexual minorities; indeed, the majority of interviewees were situated outside, or had relocated from, the countries under investigation. Given the sensitivity of this subject matter, we have randomly assigned each interviewee an alphanumeric identifier, allowing quotes to be attributed to them anonymously.

In criminological research, self-reported victimization surveys serve to identify the volume of unreported and unrecorded crimes that are excluded from official police statistics (Hough and Maxfield Reference Hough and Maxfield2007). In our area of research, however, such statistics are largely unavailable: states choose not to record or publish them, victims cannot speak out because they have been killed, and families are often silenced by the stigma of sexual “deviancy” (Interviewee I-1). Accessing basic information, such as the number of executions carried out for engaging in consensual same-sex intimacy, was no easy task. States that have the capacity to record and monitor their own criminal justice system choose not to disclose the full realities of their death penalty practice. Unsurprisingly, statistics are even sparser for non-judicial forms of violence (Interviewee I-2; Interviewee I-9). In the absence of publicly available criminal justice statistics, we looked to media reports and data gathered by local activists. We do, however, recognize that media reports are a curated selection of those executions that states choose to publicize and that journalists decide to publish (Interviewee I-2; Interviewee I-10) and that the accuracy and completeness of the data gathered by local activists depend on the availability of resources and their willingness to risk their security (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 165–82).

On some topics, our interviewees disagreed, underscoring the extent to which the realities of state persecution are largely unknown. For example, when asked about the extent to which Iran coerces same-sex-attracted persons to undergo sex-reassignment surgeries, some claimed that the state “strongly encourages” such procedures (Interviewee I-2; Interviewee I-10), while another individual recalled them “being publicized quite well” (Interviewee I-4). Conversely, one strongly disagreed, insisting that “there is no force” to undergo such procedures (Interviewee I-11). These hurdles suggest that our findings are but the tip of the iceberg. While we have made efforts to triangulate the findings, this study is an illustrative, rather than an exhaustive, account of the state-enabled killing of same-sex-attracted persons. To our knowledge, this is the first study examining such violence in this manner.

STATE-ENABLED KILLING OF SAME-SEX-ATTRACTED PEOPLE

To underscore the continuity between the death penalty properly so-called and other functionally equivalent state practices documented in the rest of this article, we subsume them under the concept of “state-enabled killing.” “Enable” is a particularly apt terminological choice: the Cambridge Dictionary (2021) gives as its meaning “to make someone able to do something, or to make something possible,” which covers all the relevant instances. To “enable” is more active than to merely permit something to happen, thus conveying the idea that state involvement in these practices is one of direct participation. This is either because the state takes the initiative in inflicting death (death penalty, extrajudicial killings) or because it authoritatively ratifies thanatoid practices by creating a regulatory landscape in which such acts are legally tolerated and socially encouraged (honor killings, gay panic defense, operation of judicial and juror biases) or because it endorses, encourages, and, in some cases, mandates the administration of life-threatening interventions (conversion practices).

“Enable” carries another useful connotation: in a more specialized psychological register, “enable” suggests the idea of allowing or making “it possible for someone to behave in a way that damages them” (Cambridge Dictionary 2021). This definition also fits all of the cases we describe for, whether state law enables public actors (as in the case of the death penalty and extrajudicial killings) or private ones (as in the case of conversion practices, honor killings, or the gay panic defense) to carry out the killing of same-sex-attracted people, it ratifies or encourages their commitment to a damaging way of life that fails adequately to apprehend or recognize the value of queer lives. Thus, the expression “state-enabled killing” also implies something important from the point of view of moral philosophy.

A legal pluralist perspective assists us in appreciating the continuity between state-enabled killing of same-sex-attracted people and instances in which state law formally provides for the death penalty. Critical legal pluralism facilitates this appreciation by acknowledging the irreducibility of normative conflict within state law as well as by collapsing, or blurring, the distinctions between (1) formal legal prescriptions and normative orders that work synergistically with state law; (2) what is habitually or systematically the case in respect of state practices and what the law formally provides ought to be the case; and (3) de facto and de jure authority. Each of these will be addressed in the sections that follow.

Unlike the monist perspective adopted by much legal scholarship, some of these dynamics can be appreciated not only through the aid of critical legal pluralism but also through a sociological analysis relying on so-called “institutional theory.” This approach centers the ways in which modes of governance tend to be the result of the complex interaction between more or less authoritative, and more or less enforceable, formal and informal systems of norms. Institutional theory theorizes different models of such interaction, often foregrounding the question of their efficiency and “organizational performance” as multi-layered institutional environments (Nee and Ingram Reference Nee, Ingram, Mary and Nee1998, 34), depending on the ideological congruence between the systems of norms interacting, the nature of their enforcement mechanisms, and, sometimes, the benefits of informal “welfare-maximizing” normative systems (Ellickson Reference Ellickson1991, 94) and the social costs associated with enforcing “dysfunctional or obsolete” ones (Peng Reference Peng2010, 780).

There are three main reasons why we do not explicitly invoke institutional theory and prefer to rely on a critical legal pluralist perspective. First, we find legal pluralism to be more conducive to the kind of “involved” (that is value-inflected, prescriptively oriented) critical analysis of state-enabled killing that we want to offer (Rubin Reference Rubin1997, 529). Institutional theory need not be seen as inherently impervious to critical and prescriptive projects, of course, but we think it telling that institutional theory, where it does involve itself in substantive evaluation of the normative desirability of different systems of rules, tends to drift (as our quotes in the previous paragraph show) into the more detached vocabulary of economics. The fact that critical legal pluralism (unlike institutional theory) developed within the context of legal scholarship (rather than the social sciences), where debates about values and what should be the case are the order of the day, offers us—so we feel—a more congenial analytical space in which to frame our arguments.

Our second reason for preferring a critical legal pluralist framework is that institutional theory, by its very nature, focuses on institutions. While “institutions” and “norms” are often used interchangeably in institutional theory literature, the focus of much of this scholarship, in practice, seems to be on institutions in the sense of communities constituted by rules rather than rules (norms) as such. Thus, institutional theory tends to foreground communities of social actors that are committed to, bound by, and enforcers of particular systems of rules. Questions about how and why those communities came to be constituted by and committed to those rules, as well as about the sources of those rules and their relationship to sources of formal law, then, become significant. These are all fascinating questions, but, at best, we could do no more than gesture toward the complexities that they give rise to in respect of the many concrete instances of state-enabled violence that we cover in this article. Critical legal pluralism enables us to bracket these questions by pitching our analysis of these case studies at a more macro level. We do so by conceiving of the normative orders that interact with state law less in terms of specific institutions and more in broader discursive formations that act like diffused regulatory regimes, such as homophobia, patriarchy, or honor, whether or not they also happen to be constitutive of discrete communities that systematically enforce their prescriptions.

The third reason for this article’s choice to utilize a critical legal pluralist perspective is that institutional theory often presupposes the internal coherence of the normative systems whose interactions it studies. However, true to its post-modernizing tendencies, critical legal pluralism is not committed to any such assumption of internal coherence. As such, it enables us to throw into relief that special class of cases where state law is in tension with itself, there being incoherence between its overt and covert normative commitments. This, in turn, means that normative incongruity between state norms and societal ones may only be apparent. Many of the cases of state-enabled killing that we discuss below fall precisely into this category: here, the fact that state law does not formally provide for the death penalty, far from signifying an ideological conflict between it and other concurrent normative orders committed to inflicting lethal homophobic violence, points instead toward a relationship of (at least partial) ideological congruence between themFootnote 16 or between key institutional actors within state and non-state normative environments.Footnote 17

THE DEATH PENALTY

While the purpose of this article is to underscore the utility of looking beyond the death penalty, to exclude the death penalty from this discussion would be remiss. Indeed, as the most visible and incontrovertible form of state-enabled killing, this is perhaps the most natural point of departure. At the time of writing, death sentences may be lawfully—that is, on the basis of codified laws or unwritten Sharia precepts—meted out for same-sex intimacy in eleven countries (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 31–32). In recent years, at least two of these countries—Iran and Saudi Arabia—have carried out judicial executions on such grounds (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 32).

Between 2004 and 2020, Iran executed at least seventy-eight men for livat (penetrative anal intercourse with another man) (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 84–86). Juvenile offenders (persons who committed crimes as children) have been among those executed, despite the fact that international law—including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to which Iran is party—prohibits the use of the death penalty in such instances.Footnote 18 While many of the seventy-eight men executed were convicted of same-sex rape, this is not necessarily an accurate representation of reality: in some cases, consensual sexual partners have reportedly exploited legal loopholesFootnote 19 and presented as rape victims to avoid the death penalty (Interviewee I-2) or to avoid the stigma associated with being gay (Interviewee I-12). Moreover, where “offenders” have been convicted of consensual same-sex intimacy, political pressures—both domestic and international—have inspired the distortion of consensual acts into rape in media reports in an attempt to make the ensuing executions more palatable to the masses (Interviewee I-2; Interviewee I-3; Interviewee I-15). The compounding of these factors suggests that the seventy-eight executions identified may well be but the tip of the iceberg: “The lack of transparency and lack of due process make it very difficult to figure out what is happening in Iran’s criminal justice system, and in particular for crimes such as this one, where the State tries to hide it from the international community” (Interviewee I-2).

In 2019, Saudi Arabia beheaded thirty-seven men convicted of terror-related offences, five of whom were additionally accused of having engaged in same-sex intimacy (Qiblawi and Balkiz Reference Qiblawi and Balkiz2019). While this may appear to be a peculiar stacking of charges, it is common for same-sex sexual acts to be bundled together with other more heinous offences, such as terrorism, murder, child abuse, and rape (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 74). For instance, prior to these 2019 executions, the most recently reported executions for same-sex sexual conduct took place in 2000 and 2002, and both cases involved the bundling together of same-sex offences with offences against children, among others (74). Given that Saudi Arabia is ostensibly willing to carry out executions for other offences, the infrequency of executions for same-sex sexual acts, coupled with the fact that persons executed for such acts are typically charged with myriad offences, suggests that these executions serve a declaratory purpose, whereby the state is striving to reinforce its homophobic position while concomitantly mitigating domestic and international condemnation: “In places like Saudi Arabia and Iran … they look for egregious behaviour that is known to the public and that won’t risk any political capital in execution, and then execute as an opportunity to send a chilling message to everyone else. Execution is much more political than it is about stemming crime” (Interviewee I-17).

It should be noted, however, that, despite reported executions for same-sex intimacy being infrequent, Saudi Arabia continues to persecute same-sex-attracted persons in other fora—for instance, in 2016, thirty-five people convicted of sodomy were sentenced to terms of imprisonment, despite the prosecution calling for the death penalty (Lavers Reference Lavers2016). Moreover, executions may well be happening in secret:

It’s extremely difficult to document the violation of LGBT rights and the prosecution of LGBT people in Saudi Arabia. … When it comes to the death penalty, we haven’t documented in recent years the actual implementation of the process against LGBT people. That is not to say that it doesn’t exist—but when it does, it’s very hidden and not really talked about in the press. It’s also very difficult to reach the Saudi Government for any type of comment because of their complete rejection of the existence of LGBT people. (Interviewee I-16)

While only these two states have been identified as actively carrying out executions on the basis of same-sex intimacy, the mere retention by nine other countries of laws enabling such executions is worthy of comment. The dormancy of such laws does not mean that their existence goes unnoticed; indeed, they have significant extra-legal implications on same-sex attracted persons: “Even if laws are not actively enforced—that is, there have not been any recent prosecutions—they have a chilling effect on the ability of LGB people to live their lives in dignity and equality. When the law treats heterosexual persons and LGB persons unequally, it sends a message to society that they can do the same” (Gerber and Dawson Reference Gerber, Dawson and Gerber2020, 16).

The implications of discriminatory legal provisions, even when left unattended by the state, are twofold. First, the existence of such laws impedes the ability of same-sex-attracted persons to realize and enjoy their rights as full citizens. For instance, in 2019, Brunei Darussalam introduced the death penalty for various offences, including sodomy. Despite the state subsequently confirming that its existing moratorium on the death penalty would be extended to cover these new provisions, it has been observed that such laws would nonetheless “have a significant chilling effect on the legitimate exercise of human rights” by sexual minorities (United Nations Secretary General 2019, 5). Second, even in the absence of judicial executions, the state’s formal prescription of same-sex-attracted persons as deserving of death perpetuates homophobic rhetoric and tacitly instructs society that the killing of such persons is justified. Indeed, many of the forms of state-enabled killing discussed in this article may be traced back to the existence of such provisions.

While same-sex intimacy may carry the death penalty in as many as eleven countries,Footnote 20 we contend that at least twenty-three statesFootnote 21 enable the killing of same-sex attracted persons (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 19). In some cases, these killings are carried out by state actors in the absence of lawful authority (“extrajudicial killings”). In others, lawful excuses to homicide and biases in judicial decision-making legitimize, and thus encourage, the killing of same-sex-attracted persons by private actors. Some states have even endorsed “conversion therapies” of such inherent violence that they lead to death or pose significant risks to life. It is these forms of killings to which we now turn. We unpack each of these forms of violence and, in doing so, reveal the complicity of states and the consequential importance of adopting a pluralistic approach, such that these killings can be viewed as “state-enabled” and functionally equivalent to the death penalty.

EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS

By their very definition, judicial executions conform to a monistic conceptualization of law, insofar as they are manifestations of legislative provisions or unwritten Sharia precepts that constitute the formal law of the state responsible for carrying them out. Proponents of legal monism would submit, by the same token, that the factors precipitating extrajudicial killings ought to not be construed as law. Here lies the fundamental drawback of a monistic perspective on state law in the context of identifying state involvement in the killing of same-sex-attracted people: the fact that the killing of same-sex-attracted persons is not mandated in formal legal provisions in accordance with the rule of recognition (Hart Reference Hart2012, 79), and is administered without lawful authority, does not make it any less real for those who face it, nor any less a matter of normatively oriented conduct for state authorities participating in it. Indeed, both judicial and extrajudicial killings have identical outcomes.

The absence of formal provisions prescribing the death penalty cannot be taken as conclusive evidence of a state’s normative commitment against punishment by death for same-sex sexual activity if state authorities operate in accordance with a conflicting set of norms—at least where the conduct is sufficiently concerted and systematic and able to be carried out with impunity. Indeed, it is this inconsistency between the formal laws of a state and the actions of its actors that demands a departure from legal monism, as the following case study demonstrates. Between 2017 and 2019, state-perpetrated “gay purge” campaigns were carried out in Russia’s Chechen Republic: same-sex-attracted people—predominantly men—were disappeared and tortured by state authorities. The first wave of violence took place in early 2017, when more than one hundred men were held in covert locations and subjected to unimaginable brutality (Lokshina, Knight, and Ovsyannikova Reference Lokshina, Knight and Ovsyannikova2017; Russian LGBT Network and Milashina 2017). While many of the men were released, this did not signal an end to their persecution; instead, authorities encouraged the men’s relatives to kill them, promising immunity from prosecution should they do so (Russian LGBT Network and Milashina 2017, 16). During this first wave of violence, at least three men are known to have been killed (30). In December 2018, a second wave of disappearances commenced, and activists have confirmed at least two further deaths as a result of torture (Prilutskaya Reference Prilutskaya2019). The true number of deaths is likely to be far greater, as both enforced disappearances and so-called “honor killings” are largely invisible forms of violence.

Chechen society is deeply conservative and masculinist, underpinned by heteronormative values with which male homosexuality fundamentally conflicts and against which it therefore offends (Lokshina, Knight, and Ovsyannikova Reference Lokshina, Knight and Ovsyannikova2017, 2). Indeed, this is reflected in the victimology of the purges: of the more than 130 people known to have been terrorized by this brutal campaign, only four were women (Interviewee I-7). It is worth noting that this trend is not unique to the Chechen Republic: a 2018 study of twenty-three countries across Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America found that attitudes toward gay men were more negative than those toward lesbian women in all twenty-three countries (Bettinsoli, Suppes, and Napier Reference Bettinsoli, Suppes and Napier2020, 701). In the Chechen Republic, this gender disparity may be the result of women holding diminished citizenship in Chechen society; accordingly, overrepresentation of same-sex-attracted men amongst the victims of the purge campaigns ought not to be construed as tantamount to state acceptance of same-sex intimacy between women but, rather, the relative invisibility of women to the Chechen authorities (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 53). As one interviewee described, “the Government does not recognise them as citizens” (Interviewee I-7).

However, women are by no means immune from violence in Chechnya. While same-sex-attracted men have been more readily brutalized at the hands of the state, same-sex-attracted women are more likely to be victimized in the private sphere: “Women are rarely imprisoned—but women have a different status in Chechen society. They lack their subjectivity. They are not viewed as citizens, as having full rights. They are in the possession of their families, and the male members of the family feel that they can do anything towards these women—so a lot of honor killings happen” (Interviewee I-7). Homophobia is so deeply entrenched in the fabric of Chechen society that the stigma attached to sexual diversity extends to the families of same-sex-attracted persons, inspiring relatives to carry out so-called “honor killings” to cleanse the family name. Indeed, the authorities are reported to have actively encouraged such killings (Lokshina, Knight, and Ovsyannikova Reference Lokshina, Knight and Ovsyannikova2017, 2).

In addition to being characterized by homophobic violence on a level unseen in recent history, this coordinated spree is particularly notable for having been carried out in a country where same-sex sexual conduct is legal: Russia decriminalized same-sex intimacy in 1993 (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 107). However, as this case study illustrates, lawfulness is not necessarily a corollary of safety or security, nor is it reflective of social and cultural attitudes: a 2020 survey revealed that a mere 14 percent of Russians deemed homosexuality acceptable, falling far short of the 52 percent median among the thirty-four countries surveyed (Poushter and Kent Reference Poushter and Kent2020, 7).

Legal monism is dangerously blind to these contradictions. The absence of legal proscription is no guarantee against state complicity in the killing of same-sex-attracted persons. Yet a monistic approach discounts the homophobic sociocultural values that—in the same way that codified laws enable the state to execute those convicted of same-sex intimacy—engender extrajudicial violence of this nature. The complicity of the state in the Chechen “gay purges” is unequivocal and no less direct than in the judicial executions of Iran and Saudi Arabia (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 54). Accordingly, we contend that the forces underpinning such violence are—and must be viewed as—law.

QUASI-JUDICIAL EXECUTIONS

In 2015, a “parallel justice court” in Afghanistan sentenced two men and a seventeen-year-old boy to death for alleged same-sex intimacy. The executions were meted out by way of “wall toppling,” the crushing of offenders under a falling wall (United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan 2016, 51). Despite the executions being preceded by some semblance of judicial proceeding, the operation of such mechanisms remains both illegal and illegitimate under Afghan law; thus, the terming of such executions as “judicial” would be remiss (51). That being said, to term such violence “extrajudicial” would be similarly inaccurate. It has been observed that violence of this nature “[b]lur[s the] boundaries between what could technically be considered an instance of enforcement of the death penalty and extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions carried out by non-official justice mechanisms ran by power factors that may have effective control over a portion of the State’s territory” (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 41). Acknowledging the dubious nature of the trials preceding such executions, and the illegitimacy with which the non-state actors under examination attain and maintain their authority, we have, for these purposes, termed such executions “quasi-judicial.”

Given that executions of this nature are conducted in the absence of formal legal authority, legal monism would contest our claim that such killings are substantiated on law. Here, the crux of the issue lies in the very notion of “formal legal authority.” Roughly, legal monism deems authority “formal” when it gains domestic and international recognition—that is, “formal” law is equated with “official” state law—and disregards those systems that operate without such authority. In fact, the term “quasi-judicial” conforms to a monistic conceptualization of law by suggesting that legal proceedings beyond the official domestic system or falling short of international standards are accordingly illegitimate. Indeed, such proceedings are illegitimate under domestic and international laws, monistically construed. In practice, however, the distinction between judicial and quasi-judicial killing can be seen as little more than a semantic one: the illegitimacy, and, indeed, illegality, of killings commissioned by an unrecognized authority are of no real consequence to persons subjected to, or threatened with, such forms of killing (and to those who love them) if that authority has de facto power. The absence of domestic and international recognition of the legitimacy of a legal system is of little, if any, significance within the context in which the quasi-judicial proceedings are conducted.

While the preceding example involves an illegitimate judicial process carried out in parallel to official state judicial processes, in some instances, insurrectional movements have succeeded in ousting governments—and, by extension, legal authority—from territories over which they subsequently command de facto governance.Footnote 22 Between late 2014 and December 2017, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) controlled swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria (BBC News 2018) and proclaimed that, within its self-declared “caliphate,” “the religious-sanctioned penalty for sodomy is death, whether it is consensual or not” (Mendos Reference Mendos2019, 523). During this period, ISIL is reported to have brutally executed more than thirty same-sex-attracted or gender-diverse people in Iraq alone (IraQueer 2018, 14), including women (MADRE et al. 2019, 8) and children (Mendos Reference Mendos2019, 138–39), often following quasi-judicial “trials.” Executions were carried out by way of shooting, beheading, stoning, or by throwing the “offender” from a building, and they are corroborated by photographic or video evidence disseminated online by ISIL itself (OutRight Action International 2016b). ISIL has similarly convicted and executed same-sex-attracted people in Libyan and Syrian cities under its control (Mroue Reference Mroue2015; Reid Reference Reid2015).

It is important to recognize that the violence to which queer persons in Iraq are subjected stems from myriad sources, many of which are neither insurrectional nor quasi-judicial. For instance, in 2014, the “League of the Righteous” beheaded two teenage boys suspected to be gay (Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq, International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission and MADRE 2014, 2). In fact, violence perpetrated by ISIL represents only the tip of the iceberg: between 2015 and 2018, ISIL was responsible for only 10 percent of crimes committed against queer persons. Militias were the most prolific aggressors at 31 percent, while 27 percent of incidents occurred within families, and a further 22 percent were commissioned by the legitimate Iraqi government (IraQueer 2018, 13). Indeed, it has been estimated that in 2017 alone, more than 220 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) Iraqis were killed by various actors (MADRE et al. 2019, 5). These figures reveal the extent to which homophobia is entrenched within Iraq’s social fabric, “permeat[ing its] institutions and society (3).

Quasi-judicial executions by insurrectional movements are not unique to ISIL. In Somalia, al-Shabaab militants exercise de facto governance over certain areas, in which they enforce their own strict interpretations of Sharia law (Ministry of Immigration and Integration 2020, 7). In 2017, an al-Shabaab court convicted two men, aged fifteen and twenty, of engaging in same-sex sexual conduct and publicly executed them by shooting (Akwei Reference Akwei2017; Omar Reference Omar2017). Moreover, in some instances, insurrectional groups execute sexual minorities without any semblance of criminal proceeding. In Yemen, for example, the Houthi rebels, who have held significant swathes of territory since 2013, are reported to have killed numerous same-sex-attracted people (Mendos et al. Reference Mendos, Kellyn Botha, López de la Peña, Savelev and Tan2020, 85).

Critical legal pluralism, determined as it is to expand our understanding of what constitutes state law, prompts us to question the significance of differentiating between cases in which punishment by death is administered by movements that usurp state authority and cases where the death penalty is provided for de jure. Phenomenologically, it is hard to imagine that the distinction would register for those who are at the mercy of the relevant authorities. Indeed, treating the two cases as being on a par is normatively warranted if it is true, as we believe, that legitimate authority is not an all-or-nothing affair and that legitimacy expands and contracts in accordance with what Joseph Raz (Reference Raz2006) calls the “normal justification thesis” and the “independence condition.” According to Raz (Reference Raz2006), authority—that is, the right to rule—is justifiable only to the extent that authoritative directives enable their subjects to better conform with right reason and, then, only if the directives concern matters in respect of which it is not more important to make up one’s own mind. State laws that punish same-sex sexual activity, whether with death or otherwise, meet neither of these conditions, for it is neither the case that engaging in same-sex sexual activity is per se acting against reason (normative justification thesis) nor that one’s choice of fully consenting sexual or romantic partner is a legitimate matter for state law to have a say on (independence condition).

It follows that there can never be a de jure (legitimate) authority providing for capital punishment for same-sex sexual activity. This vindicates the pluralist hunch that de facto capital punishment for same-sex sexual activity is analytically and normatively the same as its de jure equivalent: official state authorities providing for and inflicting death on same-sex-attracted people are scarcely distinguishable from insurgent movements taking control of a territory and doing the same.

STATE COMPLICITY IN KILLINGS BY NON-STATE ACTORS

In this section, we consider killings of same-sex-attracted persons in which the complicity of the state is indirect. We argue that a less direct involvement in the killing is by no means tantamount to a less active involvement; rather, the involvement is simply removed from the act of killing itself. For instance, the existence of culpability-mitigating laws enabling honor killings ought to be framed as a conscious decision of the state to enact, and subsequently allow killers to rely on, such provisions. Honor killing laws, the gay panic defense, and lethal or near-lethal conversion practices are all indicative of the state’s irreconcilable normative commitments. A monistic conception of state law as internally consistent and unitary, rather than radically incoherent and plural, obscures this point. How can the state have no sufficient interest in providing for the death penalty for same-sex sexual activity, yet families and private individuals have legally cognizable and legally privileged interests in administering death to those whom they may merely suspect to be same-sex attracted?

One could try to argue that, in these cases, states are not acting inconsistently because there is a morally significant distinction between permitting and excusing death and carrying it out directly. But critical legal pluralism frees us of the urge to attempt to reconcile such normative incongruities by belaboring such distinctions, enabling us instead to see that such intellectual labor—in yielding a picture of state law as committed to (the virtue of) integrity (Dworkin Reference Dworkin1986)—has a legitimating effect on thanatoid state legal practices. For to legally excuse queer killing because of the shame that queerness brings to a family, or because of the intense discomfort that straight men might feel when they are (or imagine themselves to be) desired by other men, is ultimately to say that avoiding family shame or straight discomfort matters more, both legally and socially, than queer life.

The three forms of killing examined in this section are also indicative of how state law and non-state-based normative orders—namely, the regulatory regime of societal homophobia—interact in ways that produce phenomenologically significant material consequences. Societal homophobia relies on state complicity (its legislating of honor killing laws, its continued acceptance of the gay panic defense, and its endorsement of conversion practices) to enforce, upon pain of death, its normative standards. Meanwhile, for state law, it is business as usual, despite the death that it knowingly facilitates. For those at the receiving end, it is likely that, under these circumstances, state law is experienced as itself committed to homophobia—this is to say, that state law will be experienced as participating in a broader mode of governance based on the legitimacy of dread of same-sex-attracted people.

Honor Killings

Around the world, states provide lawful excuses to those who kill same-sex-attracted people, the operation of which serves to reduce, or altogether remove, criminal responsibility for the killing. In some jurisdictions, this takes the form of culpability-reducing honor killing laws—that is, where the state carves a legislative distinction between so-called “honor killings” and murder, mitigating the culpability and consequential punishment of those who claim to have killed a same-sex-attracted person in an attempt to uphold the honor of their family or community.

A 2018–19 survey found that, in various jurisdictions throughout the Middle East and North Africa region, honor killing enjoys greater support—that is, it is more socially accepted—than homosexuality (BBC News 2019). While the sociocultural factors giving rise to such violence may vary between countries and cultures, the overwhelming majority of honor killings are perpetrated within the family unit and among those victimized by such violence are sexual minorities (United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights 2011, 9). While persons of any sex or gender may be subjected to honor-related violence, women are disproportionately victimized, and the compounding of marginalized identities renders queer women particularly vulnerable (Independent Advisory Group on Country Information 2019, 8).

Afghanistan,Footnote 23 Libya,Footnote 24 and SyriaFootnote 25 are among those states that have passed legislation explicitly distinguishing honor killing from murder, offering reduced penalties for perpetrators of the former. In other jurisdictions, lawmakers have crafted less overt legislative loopholes through which persons having committed honor killings may seek to have their culpability and sentence diminished. For example, Article 301 of the Islamic Penal Code of Iran precludes the imposition of the death penalty where an honor killing is carried out by the father or paternal ancestor of the victim (OutRight Action International 2016a, 28). Similarly, Article 302 provides that a killer may avoid both the death penalty and the payment of “blood money” upon establishing that the victim had committed a capital offence—including same-sex intercourse (Amnesty International 2021; Iran Human Rights 2021). The extent to which these legislative provisions have been engaged remains unclear, due to the opacity of Iran’s criminal justice system. Nonetheless, in light of numerous reports of honor killings of queer persons in Iran, the mere existence of these laws is a way by which the state maintains and endorses the social value of honor-related violence (Iranian Queer Organization 2011, 10; Dehkordi Reference Dehkordi2020; Interviewee I-10).

Unlike Iran, consensual same-sex intimacy is not criminalized in Jordan; however, heteronormative values and anti-LGBT sentiment persist. A 2013 study of Jordanian youth showed that 70 percent of boys and 33 percent of girls considered killing to be justified when committed so as to preserve honor (Eisner and Ghuneim Reference Eisner and Ghuneim2013, 410). Another study found that while 95 percent of Jordanian adults disapproved of honor killings, 72 percent nonetheless believed Jordanian culture to necessitate honor killings where a family member has tainted family honor by being “promiscuous” (Kulczyki and Windle Reference Kulczycki and Windle2011, 1454). Finally, a 2018–19 survey concluded that, while 21 percent of Jordanian respondents deemed honor killings acceptable, only 7 percent were supportive of homosexuality (BBC News 2019). While concrete evidence is difficult to ascertain, it has been reported that multiple honor killings motivated by sexual orientation have been committed in Jordan (Alami Reference Alami2014).

Historically, killers claiming to have killed “in a fit of fury … motivated by dishonourable and provocative behaviour of the victim” could seek a reduced sentence.Footnote 26 These provisions have been enacted on at least one occasion: a father who killed his lesbian daughter in an attempt to restore the honor of his family was sentenced to a reduced term of imprisonment (Dunbar Reference Dunbar2019). While recent legislative amendments have limited this provision exclusively to instances in which a male offender kills his wife or female relative, or their lover, “in a state of adultery or illegitimate bed,”Footnote 27 scope remains for killers to seek reduced sentences where “extenuating reasons” exist.Footnote 28 A review of Jordanian case law makes clear that the most common “extenuating reason” (present in 89 percent of all murder convictions between 1999 and 2014) is that the family of the victim—which also happens to be the family of the offender—chose to drop their personal charges against the defendant so as to protect the perpetrator and avoid the shame associated with the victim’s behavior (Alqahtani Reference Alqahtani2019, 175, 179).

In both Iran and Jordan, murder is criminalized and punishable by death; it is here that the strength of a pluralist approach lies. The formal condemnation of killing and the simultaneous justification of the killing of same-sex-attracted persons is inherently contradictory; however, a monistic conception of state law would attempt to explain this away. Unlike the death penalty, honor killings are not necessarily carried out on the command of the state and on the basis of formal legal provision; thus, legal monism would posit that honor killings are not birthed by law. However, the absence of formal laws mandating, or state-made orders commissioning, such killings is not to say that such killings are carried out without state authority. Indeed, in the same way that extrajudicial killings are inspired by homophobic hate, honor killings are inspired by culturally entrenched homophobic fear (that is, fear that one’s honor will be tainted by way of association with a same-sex-attracted person), and by enacting formal laws that play on such prejudices, the state perpetuates and legitimizes already pervasive homophobia. It is this state-endorsed homophobia that we contend constitutes law for it is this that inspires the killing of same-sex-attracted persons in the name of honor.

The “Gay Panic” Defense and Courtroom Biases

The so-called “gay panic” defense is a legal strategy where an accused killer—typically, a heterosexual cisgender man—seeks to have his culpability reduced on the basis of his victim’s (perceived) sexual orientation.Footnote 29 In legal terms, this argument is most commonly framed as either provocation or self-defense. When run as a provocation defense, “gay panic” is used by the defendant to justify that his killing of the victim was in retaliation to the victim making a non-violent same-sex sexual advance toward him (McGeary and Fitz-Gibbon Reference McGeary and Fitz-Gibbon2018, 578–79). The “non-violent” element is crucial: whereas violence commissioned in self-defense may in some instances be deemed warranted should the same-sex sexual advance have been accompanied by a perceived threat of harm, provocation—and the violence that such a defense seeks to justify—is grounded exclusively in homophobia.

The defense of provocation has been widely criticized as legitimizing violence and institutionalizing prejudice. It is founded upon heteronormative and patriarchal ideals, fundamentally leaning in favor of heterosexual cisgender male offenders (Plater, Line, and Fitz-Gibbon Reference Plater, Line and Fitz-Gibbon2017, 10). In mounting a provocation-based “gay panic” defense, an accused killer is constructing a narrative in which he is, in fact, the victim, claiming that he was victimized by the sexual orientation of the deceased. In effect, the accused—and, should the court accept the argument, the state—is engaging in perhaps the most egregious form of victim blaming, opining that the deceased is responsible for their own death (Plater et al. Reference Plater, David Bleby, Lucy Line, O’Connell and Fitz-Gibbon2018, 50–52).

Continued acceptance and endorsement by judiciaries of the inherently prejudiced notion of “gay panic,” coupled with the failure of legislatures to outlaw this defense, is particularly pronounced—and, indeed, shocking—in countries where recognition and protection of the rights of sexual minorities have already penetrated, and are continuing to gain traction in, the public and political consciousnesses. For instance, the “gay panic” defense remained a legal possibility in Australia until December 2020, when South Australia became the final Australian jurisdiction to abolish it.Footnote 30 The “gay panic” defense was first employed in Australia in 1992Footnote 31 and gained notoriety in 1997 when Australia’s highest court quashed a murder conviction on the basis that the killer had labored under a “special sensitivity” causing him to lose control when the victim allegedly made a sexual advance toward him.Footnote 32 The defense was raised at least eight times between 2000 and 2014 (McGeary and Fitz-Gibbon Reference McGeary and Fitz-Gibbon2018, 582) and was endorsed by the High Court as recently as 2015.Footnote 33

In the United States, in addition to being argued on the basis of provocation, “gay panic” has been used—and successfully so—to bolster claims of self-defense.Footnote 34 For instance, in 2018, a Texas jury found a man guilty of “criminally negligent homicide”—a lesser offence than murder and manslaughter—after claiming that he had killed his victim while acting in self-defense. The killer alleged that his victim had made a sexual advance toward him and became agitated after being turned down—an argument that the jury accepted, despite an absolute lack of evidence backing this claim and testimony that the victim was in fact heterosexual. Despite being prosecuted for murder, and admitting that he had in fact killed the victim, the offender was sentenced to a mere six months’ imprisonment and ten years’ probation (Compton Reference Compton2018). A study of 104 US homicide trials between 1970 and 2020 showed that the “gay panic” defense successfully diminished the culpability of offenders in 32 percent of cases, and, in four cases, the accused was acquitted entirely (Andresen Reference Andresen2020). Each of the cases reviewed fits into one of two categories, both of which challenge the veracity of the “gay panic” arguments contended in court. In 54 percent of cases, the killer also stole from the victims, while in the other 46 percent of cases, the killings were characterized by extreme violence indicative of an intention to mutilate the victim. It has been suggested that all these homicides have one sole purpose: “inflicting violence” (Andresen Reference Andresen2020).

In other jurisdictions, even where the “gay panic” strategy is not employed by the defendant, homophobic prejudices of both judge and jury may sway the outcome of a trial to similar effect. For instance, in 2019, a man punched another man in the neck, “accidentally” killing him, after the victim made a sexual advance on him. A South African court sentenced him to a ten-year suspended sentence and anger management classes, the judge reportedly saying that the killer had “reacted in a way that any other person in his situation would have” (Masuku Reference Masuku2019). Similarly, a man charged with pinning a gay man down as he was hacked to death by another perpetrator was acquitted by a Trinidad and Tobago court. In delivering its verdict, the court termed homosexuality “unnatural” and asserted that any “right-thinking person” would have acted the same.Footnote 35 Leniency has also been observed in the sentencing of persons convicted of killing on the basis of sexual orientation in the Bahamas in 2010 (Bahamas Local 2010) and Dominica in 2009 and 2012 (Amnesty International 2013, 3), while the “gay panic” defense was used in the Bahamas in 2009 (Pink News 2009) and as recently as 2019 in Jamaica.Footnote 36

While these cases reflect the influence of judicial bias on verdicts and sentencing of offenders, the consequences of jury prejudice are perhaps most notable in the case of Charles Rhines. Rhines was convicted of murder in 1993 by a US jury who knew of his homosexuality. During sentencing deliberations, the jury expressed concern as to Rhines’s incarceration alongside other men—for instance, the jury asked whether Rhines would be allowed to “mix with the general inmate population,” “discuss his crime with other inmates, especially new and/or young men,” “marry or have conjugal visits,” or “have a cellmate.”Footnote 37 When the judge failed to quell their apprehensions, the jury decided that Rhines ought to be sentenced to death.Footnote 38 Jurors later disclosed that the deliberations had been contaminated by homophobic biases. For instance, one juror recalled fearing that Rhines may be a “sexual thread to other inmates and take advantage of other young men in or outside of prison,” while another reported “a lot of disgust” in the jury room.Footnote 39 Despite irrefutable evidence of bias infecting his trial, conviction, and sentence, Rhines was executed on 4 November 2019.Footnote 40

The utility of critical legal pluralism in this context needs little explanation. In the same vein as laws mitigating culpability for honor killings, the “gay panic” defense and homophobic prejudices of judge and jury see the state endorse, and, in doing so, propound, homophobic values. The coercive force of such values must not be underestimated.

Conversion Practices

So-called “conversion therapies” arise out of the pathologization of homosexuality. Same-sex attraction has a long history of being pathologized in Western medicine. In 1886, Richard von Krafft-Ebing published his seminal Psychopathia Sexualis, in which he construed non-procreative sexual behaviors—including same-sex sexual acts—as forms of psychopathology (Drescher Reference Drescher2015, 568). Sigmund Freud refuted Krafft-Ebing’s approach, instead viewing same-sex attraction as an incurable manifestation of “arrested” psychosexual development (that is, immaturity); however, post-Freudian psychoanalysts reverted to the idea of homosexuality as psychopathological (569). In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1952) published its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in which homosexuality was classified as a “sociopathic personality disturbance.” After a series of revisions in which same-sex attraction was termed “sexual deviation,” “sexual orientation disturbance” and then “ego dystonic homosexuality,” the APA finally declassified homosexuality altogether in 1987, with the World Health Organization following suit in 1990 (Drescher Reference Drescher2015, 571).

Despite Western medicine’s depathologization of same-sex attraction gaining widespread acceptance, the idea of homosexuality as a curable illness persists. In many countries around the world, such practices are endorsed by the state and, in some cases, have directly resulted in the death of the individual subjected to these cruel and inhumane treatments. Thus, the “law” in question here is the state’s acceptance of same-sex attraction as a curable affliction and its consequential endorsement of life-threatening “cures.” The term “conversion therapies” refers to “any sustained effort to modify a person’s sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression” (Mendos Reference Mendos2020, 17). They are premised on the misguided assumption that sexual orientation “can and should be changed or suppressed when they do not fall under what other actors in a given setting and time perceive as the desirable norm” (Madrigal-Borloz Reference Madrigal-Borloz2020, 4). Given the scientific baselessness of these interventions, we use the term “conversion practices” instead.

A 2020 review identifies conversion practices as occurring in at least sixty-eight countries (Bothe Reference Bothe2020, 5). Of course, not all such practices are necessarily state enabled—for instance, extremely violent interventions such as exorcisms have been documented as being carried out in religious spaces by faith leaders and organizations (Mendos Reference Mendos2020, 43–45), who continue to be some of the leading proponents and practitioners of conversion practices (Madrigal-Borloz Reference Madrigal-Borloz2020, 6–7). That being said, at least eighteen states are complicit in the carrying out of conversion therapies (Sato and Alexander Reference Sato and Alexander2021a, 74). The manner and degree of state involvement varies between countries: in Tajikistan, police have reportedly subjected sexual minorities to “corrective violence” (Bothe Reference Bothe2020, 12), while, in Tunisia, children have been subjected to judicially ordered psychiatric internment (15). In Dominica, psychiatric treatment is even a legislated penalty for consensual same-sex intimacy.Footnote 41

In the majority of cases, conversion practices—while inflicting a plethora of harms—do not lead to death. In cases where death does ensue, this is overwhelmingly as a result of suicide. Accordingly, to suggest that conversion practices are a form of state-enabled killing may be somewhat controversial, particularly given that, unlike the other forms of killing previously mentioned, proponents and practitioners of conversion practices do not necessarily set out to kill sexual minorities or excuse the killing. Rather, such practices are premised on the fundamentally skewed notion that sexual diversity may be “cured.” Nonetheless, we are aware of at least five deaths that have occurred as a direct result of conversion practices: one caused by a drug therapy overdose (Interviewee I-9), another by electroconvulsive therapy (Interviewee I-9), and three as a result of grossly improper sex-reassignment surgeries and inadequate post-surgical care in Iran (Bahreini Reference Bahreini2014, 158). It is entirely possible—if not likely—that further deaths have gone undetected and unreported given the often clandestine nature of conversion practices.

When carried out with due diligence and for their proper purpose, sex-reassignment surgeries—a form of gender-affirming care—are neither dangerous nor dubious. Indeed, such surgeries may have life-changing positive effects on persons having undergone such procedures. In Iran, however, the situation is radically different: sex-reassignment surgeries have reportedly been performed on sexual minorities, on the misapprehension that the surgical alteration of same-sex-attracted persons’ sex characteristics is capable of transforming them into “gender conforming men or women,” bringing them in line with heteronormative expectations (Interviewee I-2; Interviewee I-10).

Of particular concern is the fact that the Iranian state promotes and funds these procedures, hence the classification of any preventable deaths occasioned by such procedures as state enabled (Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 2013, 3). Moreover, the fact that this “official policy” is promulgated in a country where same-sex intimacy is punishable by death is indicative of “a far more nefarious agenda” on behalf of the state (Carter Reference Carter2011, 799). The simultaneous condemnation of same-sex intimacy and endorsement of sex-reassignment surgeries births a precarious ultimatum requiring that the same-sex-attracted person choose between unnecessary and potentially lethal medical procedures and the possibility of the death penalty, the latter constituting “a powerful incentive” for the same-sex-attracted person to undergo the former (Sanei Reference Sanei2010, 81). Testimonial evidence from same-sex-attracted Iranians and activists alike corroborates the very real implications of these intersecting policies, noting that this ultimatum is not only a theoretical one, but is in fact played on by the state to coerce individuals into undergoing surgical intervention (Bahreini Reference Bahreini2014, 114–16; Interviewee 2; Interviewee 4; Interviewee 10).

In the interests of completeness, sex-reassignment surgeries are but one of many ways in which the Iranian state intervenes in the lives of sexual minorities, putting those very same lives at immense risk. For instance, armed with the tacit approval of the state, mental health practitioners have diagnosed and “treated” the sexual “deviancy” of hundreds of Iranians, often with electroshock therapy or the prescription of strong psychoactive medications (Sanei Reference Sanei2010, 38–41). It goes without saying that such practices are inherently dangerous, and potentially even life threatening, particularly when administered improperly or in conditions falling far short of medical and ethical standards.

Beyond Iran, conversion practices have been identified as taking many forms of physical, psychological, and sexual violence of varying degrees of brutality (see, for example, Madrigal-Borloz Reference Madrigal-Borloz2020). In addition to the physical harms occasioned by such violence, the psychological implications of such practices are reported to include “significant loss of self-esteem, anxiety, depressive syndrome, social isolation, intimacy difficulty, self-hatred, shame and guilt, sexual dysfunction, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts” (Madrigal-Borloz Reference Madrigal-Borloz2020, 13–14; emphasis added). Of course, suicide must be distinguished from state-enabled homicide; however, to absolve states of all responsibility for suicides stemming from conversion practices in which states themselves are complicit is unacceptable. Indeed, the United Nations Human Rights Committee (2018, 2) has observed that the right to life should not be narrowly construed and that states ought to take sufficient measures “to prevent suicides, especially among individuals in particularly vulnerable situations.” The vulnerability to suicide of persons subjected to conversion practices is incontrovertible; suicide has been identified as a real risk of conversion practices, and policy makers have been called upon to take measures to prevent these “completely unfair, avoidable deaths” (Mendos Reference Mendos2020, 62).

The philosophy of science recognized long ago that political and moral values structure research agendas and knowledge production, as much in the medical field as elsewhere (Kuhn Reference Kuhn1962). It is not surprising, therefore, that states may adopt radically different positions as to the interpretation of different scientific findings and the weight afforded to them and as to the legitimacy of practices based on them. Yet philosophers of science have also pointed out that we do have tools at our disposal to discriminate between good and bad science, including by acknowledging, rather than denying, the role that political values play in constructing knowledge and by subjecting such values to critical scrutiny (Harding Reference Harding1986). While one’s normative values may induce skepticism as to the legitimacy and propriety of any given medical practice, from a critical legal pluralist perspective, conversion practices are in fact “law” for reasons that should by now be clear. Conversion practices are indicative of how state law and non-state-based normative orders—namely, the regulatory regime of societal homophobia—interact in ways that produce phenomenologically significant material consequences. For those at the receiving end, the condemnation of same-sex intimacy through (the threat of) judicial executions and the promotion of life-threatening conversion practices as a medical “cure” for same-sex attraction are simply different modes of governance based on the legitimacy of dread of same-sex attracted people.

CONCLUSIONS

Lethal punishment for actual, perceived, or alleged same-sex sexual activity occurs in jurisdictions around the world not only when people convicted of sodomy or analogous offences are formally sentenced to death but in a number of other legally mediated ways: extrajudicial killings, killings by de facto authorities, honor killings, killings invoking the gay panic defense, and violent conversion practices leading to death. We have argued that the lens of critical legal pluralism facilitates an appreciation of why all such legally and state-mediated practices belong together. The normative implication of our argument is that they all equally demand the reform-driven attention of governments, international human rights organizations, and civil society organizations.

The value of critical legal pluralism is largely for diagnostic purposes. As a phenomenological matter, different normative orders and regulatory regimes do constrain and structure the conduct of individuals and groups. As an empirical matter, state law itself is internally heterogeneous and plural rather than a coherent whole. Critical legal pluralism as a scholarly practice helps us keep these facts in mind and guides us in our analyses accordingly. This does not mean that state law should not aspire to unity and coherence oriented toward the common good or to supremacy over competing normative orders that are not in the common good. As Paul Schiff-Berman (Reference Schiff-Berman2007, 327) points out, legal pluralism is prescriptively agnostic: it does not, in and of itself, carry with it any normative implications about what should be the case. But we do not need critical legal pluralism to tell us what to do with the instances of state-enabled killing that we have catalogued. The case for reform—indeed, a non-pluralist case for state laws to commit to coherent, across-the-board repeal of, and disengagement from, all such practices and, more broadly, to the equal dignity of same-sex-attracted people—asserts itself not only as a requirement of international human rights law but also of all reasonable people’s practical thought, whether we are drawn to an ethos of singularity or plurality.

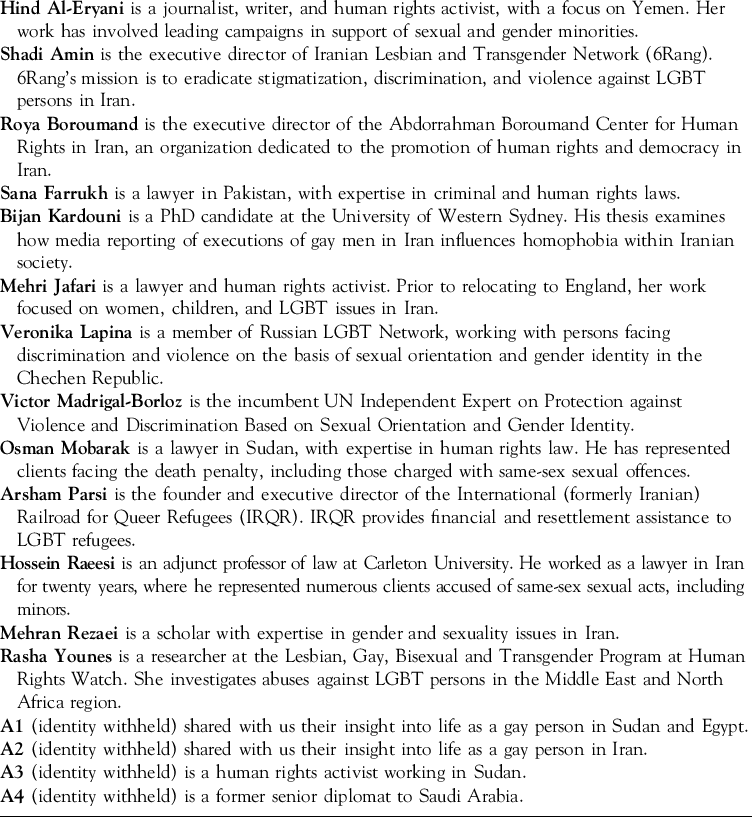

Appendix: List of Interviewees