1 Introduction

It is well known that subjects can exhibit a preference for improving sequences (Reference Loewenstein and PrelecLoewenstein & Prelec, 1993). In particular, many people prefer an increasing sequence of payments over a constant sequence, even if the increasing sequence has a lower present value (Reference Loewenstein and SichermanLoewenstein & Sicherman, 1991). However, little is known about how this preference varies with the size of the payments.

In each of the four studies that follow, we elicit preferences over sequences of payments of various amounts. Each option specifies an explicit sequence of payments over time. One option is a constant payment sequence, the base amount. The other options are increasing sequences of payments, varying in their rate of increase. Within each question, the undiscounted sum of each payment stream is identical among all response items. Therefore, the rate of the increase of the sequence is negatively related to the present value of that sequence. Hence, the chosen payment sequence provides a measure of the preference for increasing payments of the subject.

In Study 1, the preference for increasing sequences of income is stronger when the payments are larger. In order to determine if this relationship is specific to the domain of the sequence, we also elicit preferences over sequences of hours required for a job. We do not find a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the preference for decreasing hours.

One complication in studying the preference for increasing payments relates to the finding that subjects can have different preferences for increasing payments based on the source of the payments. In particular, Reference Loewenstein and SichermanLoewenstein and Sicherman (1991) find that the preference for increasing payments is stronger when the money is described as wages rather than from another source. As an explanation of the difference in the preference for increasing wage payments and nonwage payments, Reference SmithSmith (2009a) offers a model of a decision maker with imperfect memory who makes a prospective choice among payment sequences. The model predicts that the difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments will be largest for intermediate amounts.

In Study 2, we measure the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments. Similar to Study 1, we find a positive relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. Additionally, we find weak evidence in support of the predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a), that the largest difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments occurs for intermediate amounts.

A possible explanation for the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments is that it is due to decreasing marginal utility of money. Consider a subject who has a preference for money and a preference for improvements in payments. The subject is contemplating Choice A, which is between a sequence of payments with a slow rate of increase and a sequence with a high rate of increase, where the undiscounted sums are identical. Now suppose that the subject is also contemplating Choice B, identical to Choice A except that we add a constant amount to each payment in both sequences. Further, suppose that the subject selects the slow increasing sequence in Choice A and the fast increasing sequence in Choice B. The decreasing marginal utility explanation would contend that the higher payments in Choice B are less beneficial than the same increases in Choice A, so the subject will seek to compensate for this by selecting a larger rate of increase.

In order to test this decreasing marginal utility explanation, in Study 3 we also take a measure of the decreasing marginal utility over the relevant range. Specifically, we employ an Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman (2008) type measure of risk aversion, which directs subjects to select among 6 risky choices, which can be ordered by their riskiness. The response provides a measure of the decreasing marginal utility of the subject. While we again find that the preference for increasing payments is increasing in the size of the payments, we do not find a relationship between this behavior and our measure of decreasing marginal utility. As a result, we do not favor the decreasing marginal utility explanation for the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments.

In Study 4, we investigate whether the preference for increasing payments is sensitive to the nature of the construction of the sequences. We construct sequences using two different techniques: the proportional technique and the additive technique. The proportional technique, which we have used to construct the sequences in Studies 1, 2, and 3, specifies the sequences by multiplying the base amounts by fixed proportions. This implies that, as the payment sizes become larger, there is also a larger absolute increase within the sequences. In contrast, the additive technique constructs the sequences by adding fixed values to the base amounts. This implies that, as the payment sizes become larger, there is no change in the absolute increases within the sequences. We do not find evidence that the technique used to construct the sequences affects choice.

In our view, this paper makes four contributions to the literature. Although it is well known that many people have a preference for increasing payments, our first contribution is the finding that this preference is increasing in the size of the payments. The result is robust across different subject populations and appears to not be sensitive to the specification of the increases. Our second contribution is that this effect appears to not be driven by decreasing marginal utility. Third, we do not find a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the preference for improving nonmonetary sequences. Finally, our fourth contribution is the weak evidence that the difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments is largest for intermediate amounts, as predicted by Reference SmithSmith (2009a).

2 Related Literature

Research finds that people have a preference for improving sequences of outcomes. This extensive body of research extends to monetary outcomes or nonmonetary outcomes, retrospective evaluations or prospective evaluations, and short or long time horizons. Footnote 1 For instance, Reference Loewenstein and SichermanLoewenstein and Sicherman (1991) offer subjects a choice among payment sequences over 6 years. The amounts within each payment profile sum to identical amounts however each exhibit a different rate at which the payments are made. The choices include options with constant, decreasing, or increasing rates of payment. Therefore, any subject with a positive discount rate would never prefer an increasing profile. Despite the clear prediction of standard discounting, the authors find that many subjects prefer the increasing payment options. As in Loewenstein and Sicherman, we offer subjects payment sequences that sum to identical amounts within each question.

Additionally, Loewenstein and Sicherman find that the preference for increasing payments are particularly pronounced when the payments are described as “income from wages” as opposed to money from another source, which the authors describe as “income from rent”. In Study 2, we also wish to distinguish between preferences over payment sequences that require effort and those that do not require effort. However, we do not utilize the “income from rent” description because if the subject has prosocial preferences, the subject might not want to obtain an improving sequence of money by imposing a declining sequence on the person paying the rent. Therefore, in Study 2 we measure the preference for increasing payments of nonwage money by describing the payments as resulting from a large lotto jackpot won by a family member.

Reference SmithSmith (2009a) offers a model of a decision maker with imperfect memory who makes a choice involving payment sequences in exchange for work-related effort. In the model, the decision maker has an uncertain cost of effort, and before the decisions regarding effort, the decision maker receives information about the cost of effort. Subsequently, the decision maker forgets the signal but makes an inference of its content from the objective features of the decision that are not forgotten: the wage paid and the choice of effort. In this setting, the payoff of the decision maker is the utility from payment minus the perceived cost of effort.

Reference SmithSmith (2009a) shows that increasing payments imply a lower perceived cost of effort and thus a larger perceived surplus from engaging in the effort. Intuitively, this is the case because a lower payment in the first period serves to reduce the perceived cost of effort in the second period. In Study 2, we find weak evidence that the difference between the preference for increasing wages and the preference for increasing nonwage payments is largest for intermediate amounts.

Of course, we are eliciting preferences over objects that differ in the timing and amount of money to be received. When observing such choices, it is not a trivial problem to distinguish the effects due to the instantaneous preference for money and those due to time preferences. Footnote 2 In an effort to measure the former, Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman (2008) Footnote 3 offer a simple measure of risk aversion. In the Eckel-Grossman measure, the subject selects among 6 risky choices whereby riskier choices offer a higher expected value. The choice allows the experimenter to obtain a measure of the Constant Relative Risk Aversion parameter of the subject. We employ a variation of the Eckel-Grossman measure and compare the results to the preference for increasing sequences of money. We do not find evidence that this measure is associated with the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments.

There is a literature that seeks to establish a relationship between the size of a monetary payment, the delay in which it is received, and the subject’s time preference. In particular, Reference Green, Myerson and McFaddenGreen, Myerson, and McFadden (1997) offer subjects a choice between single payments, of different amounts to be paid at different times, and find a negative relationship between the implicit discount rate and the amount of the payment. Footnote 4 We perform a similar exercise in the sense that we wish to learn how the subject’s time preferences (or negative time preference in our case) varies with the size of the payments. However, to our knowledge, there has not been a study that examines such an effect on the preference for sequences of payments.

Prior research has examined whether preferences of sequences in one domain (say, money) are related to preferences of sequences in another domain (say, health). The existing evidence on this matter is mixed. Early literature found that the preference for sequences in one domain does not necessarily imply such a preference in another domain (Reference ChapmanChapman, 1996a, 1996b; Reference Schoenfelder and HantulaSchoenfelder & Hantula, 2003). Footnote 5 However, more recent papers find evidence of a similar time preference across some domains (Reference ChapmanChapman, 2002; Reference Chapman and WeberChapman & Weber, 2006; Reference Hardisty and WeberHardisty & Weber, 2009). We do not find a relationship between the preference for increasing wages and the preference for decreasing hours required for a job.

There are two primary criticisms of the preference for increasing payments literature discussed above. The first is that the evidence supporting the existence of the preference for increasing payments tends not to be robust to the method of elicitation. The second is that the responses of the subjects are not incentivized and should therefore be interpreted with caution. We now address these two criticisms.

Reference Frederick and LoewensteinFrederick and Loewenstein (2008) show that the preference for improving sequences is sensitive to the means of elicitation. Footnote 6 We design our questions in order to mitigate the spurious effects discussed by Frederick and Loewenstein. The authors list three reasons Footnote 7 regarding which a subject might exhibit a preference for improving sequences: the utility of anticipating future outcomes, a contrast effect by having a series of improvements according to a reference point, and an extrapolation effect where subjects come to believe that the payment trajectory will continue beyond that specified by the experimenter. These first two reasons are not driven by the means of elicitation, however we view the final reason to be an unwanted remnant of the methodology. Therefore, our experiments are designed to mitigate the extrapolation effect.

Another criticism is that the experimental work on the preference for increasing payments is largely not incentivized. (It is, after all, relatively difficult and expensive to experimentally manipulate a person’s income schedule.) Nonetheless, there is evidence that data generated by such experiments are useful. For instance, Reference Johnson and BickelJohnson and Bickel (2002) do not find significant differences between the measurement of time preferences involving hypothetical and actual money. Additionally, a large body of empirical evidence supports the claim that people prefer increasing payments of income. In particular, research finds that wages increase at a faster rate than productivity. Footnote 8 This would only seem to persist in the case where the workers have a preference for such improvements. In another strand of literature, researchers find that either happiness or satisfaction is significantly related to increases in wages. Footnote 9 Based on the experimental and empirical work cited above, we are confident in the relevance of the experiments that follow.

3 Study 1

3.1 Procedure

A total of 105 subjects, recruited from economics classes at Rutgers University-Camden, participated in the experiment. Sessions were conducted in classes of 19, 50, 13, and 23. Subjects were given course credit for attendance and were told that within each session, roughly 1 out of 25 subjects would be randomly drawn to win a prize of $20 in cash. Footnote 10 Instructions were provided by the same male experimenter. Footnote 11 The subjects were told to consider a hypothetical employment setting. The study posed 5 income sequence questions and 4 hours sequence questions. Each response was entered on paper.

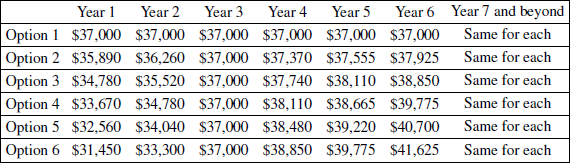

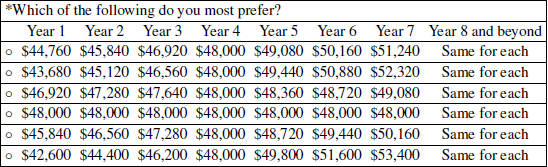

Before each income sequence question, the subjects were told that they “…are happy with nonmonetary aspects of the job…” and are offered the following options for payment over time. Each income sequence question offered subjects 6 income sequences over 6 years. The subjects were told to select the one that they most prefer. In each of the five income questions, the subject was presented with a constant sequence with a base amount of either $17,000, $37,000, $57,000, $77,000, or $97,000. The other response items within each question varied the degree to which the payments were increasing. As a result, we can associate each income question with the base amount of the sequence.

These income sequences were designed so that each sequence option, within each question, summed to an identical amount. Therefore, a subject who has a positive discount rate would select the constant sequence of income, regardless of the size of the payments. Further, within each question, the response items had identical values in the third year. However, the increasing payments each had lower incomes in the first and second years, and higher incomes in the fourth, fifth, and sixth years. Each sequence was constructed using the same proportional technique, where the base amounts are multiplied by fixed proportions. See the appendix for a sample income question and a more detailed explanation of the proportional technique.

We varied the order in which the questions were presented to the subjects. Also, we presented the options so that they were ordered by their rate of increase. Approximately half of the subjects were given the options in ascending order: the constant sequence as the first option and the most increasing sequence as the last option. Approximately half were given the options in descending order: the most increasing sequence as the first option and the constant sequence as the last option. In the analysis of the data, we recoded the responses so that Option 1 represented the constant sequence and Option 6 represented the most increasing sequence. Since the rate of increase in the selected sequence is negatively related to the present value of the sequence, and since we recoded the responses, we are therefore able to speak of a stronger preference for increasing payments as being associated with a higher chosen number.

In order to minimize the extrapolation effect, discussed in Reference Frederick and LoewensteinFrederick and Loewenstein (2008), each response item included the description “same for each” for “year 7 and beyond”. Also in an effort to minimize the extrapolation effect, the subjects were told that, at the end of the sixth year, they would either be promoted or fired, and therefore their choice of income stream would not affect their income after the sixth year. The subjects were told that the dollar amounts were listed in 2009 dollars and that their forecast of inflation should not be factored into their responses.

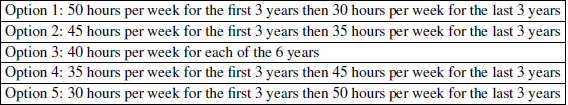

We performed a similar exercise for sequences of hours required at their job. After the income questions, the subjects were provided with a list of possible hours sequences over the next 6 years. In each of the four hours questions, the subjects were presented with a constant amount of 40, 50, 60, or 70 hours per week. The other response items in each question were increasing or decreasing step functions, with only a single step, and each summed to the same amount over the six years. See the appendix for a sample hours question. Similar to the income questions, the response items can be ordered by their rate of increase. Any subject who has a positive discount rate would never prefer a decreasing sequence of hours. As with the income questions, we varied the order of the questions and the response items.

Finally, in order to account for the heterogeneity of the valuation of the various salary amounts, we also asked for their descriptive ratings of the amounts. Specifically, the subjects were asked to provide their descriptive ratings of starting salaries of $17,000, $37,000, $57,000, $77,000, and $97,000 on a scale of 1 (very low) to 7 (very high).

3.2 Data

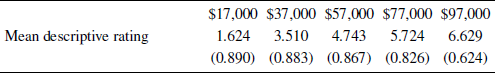

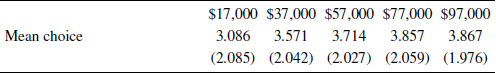

We note that 104 out of the 105 subjects offered a descriptive rating of the incomes of $17,000, $37,000, $57,000, $77,000, and $97,000 in a monotonic fashion. See Table 1 for the mean descriptive ratings by income. Table 2 shows the means of the choices for each of the income questions.

Table 1: Mean descriptive ratings of starting salaries (Study 1) by income. (Standard deviations in parentheses.)

Table 2: Mean choices in Study 1 for questions with different base income amounts. (Standard deviations in parentheses.) Higher means indicate stronger preferences for increasing sequences.

We do not find a significant difference between the choices of subjects who were given the options in ascending order and the choices of those who were given the options in descending order. Further, we do not find a relationship between preferences for increasing payments and the order in which the questions were presented.

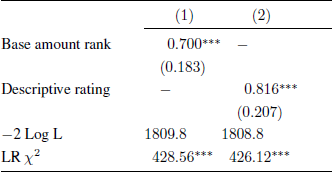

We do find a positive relationship between the preference for increasing payments

and the size of the payments. Two linear regressions provide evidence of this

result. Both regressions specify the degree of the preference for increasing

payments as the dependent variable.Footnote 12 These regressions were preformed as a repeated

measures analysis with an unstructured covariance matrix (as is also true for

analogous regressions in later studies). Regression (1) employs the rank of the

base amount within the question as the independent variable. For instance, the

question with a base amount of $17,000 is 1, the question with a base

amount of $37,000 is 2, and so on. We refer to this as the base

amount rank. For the purpose of the regression below, we code the

base amount rank as ![]() . Regression (2) uses the

subject’s descriptive rating of the base amount corresponding to the

question as the independent variable. As the descriptive rating has seven

elements, we code the variable as

. Regression (2) uses the

subject’s descriptive rating of the base amount corresponding to the

question as the independent variable. As the descriptive rating has seven

elements, we code the variable as ![]() . Since we have 105 subjects who

each made 5 income choices, both regressions have 525 observations. See Table 3 for a summary of the regression

results.Footnote 13

. Since we have 105 subjects who

each made 5 income choices, both regressions have 525 observations. See Table 3 for a summary of the regression

results.Footnote 13

Table 3: Results of repeated-measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Study 1).

Note: unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.001

As shown in Table 3, both regressions suggest a positive relationship between the preference for increasing payments and either the base amount rank or the descriptive rating of the wages. In other words, the preference for increasing payments becomes stronger for larger payments.

Study 1 allows the analysis of the relationship between the preference over sequences of monetary outcomes and the preference over sequences of nonmonetary outcomes. As a measure of the preference for increasing payments, we take the average of the rank of the options selected in the 5 income questions. As a measure of the preference for decreasing hours, we take the average of the rank of the options selected in the 4 hours questions. If subjects exhibit a preference for improving sequences across domains then we would expect a negative correlation between the variables. However, we do not find a correlation between the exhibition of a preference for increasing payments and a preference for decreasing hours, r(103) = −0.0068, p = 0.95.Footnote 14

We now examine the relationship between changes in the preference for increasing payments and changes in the preference for decreasing hours. In order to conduct this analysis, we perform a separate linear regression for each subject, with the income choice as the dependent variable and base amount rank as the independent variable. We employ the coefficient estimate as a measure of the change in the preference for increasing payments. Additionally, we perform a separate linear regression for each subject, with the hours choice as the dependent variable and the rank of the hours question as the independent variable. We employ the coefficient estimate as a measure of the change in the preference for decreasing hours. If subjects exhibit changes in the preference for improving sequences consistently across these domains, we would expect a negative correlation between these variables. However, we do not find evidence that these two variables are correlated, r(103) = −0.109, p = 0.27.Footnote 15

3.3 Discussion

Study 1 finds a positive relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of those payments. However, the study does not find evidence of a relationship between the preference for increasing wages and the preference for decreasing hours. Nor does it find evidence for consistency in the effects of base amount on relative preference for increasing sequences. Now we test the predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a) that will require the measurement of the difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments.

4 Study 2

4.1 Procedure

A total of 212 undergraduate and graduate students in the psychology subject pool at Rutgers University-Camden were recruited to participate in the experiment. The subjects were given course credit for participating.

Subjects were randomly selected to be in one of two treatments: the Job treatment or the Lotto treatment. Subjects in the Job treatment were given the identical 5 income questions as used in Study 1. In the Lotto treatment, the amounts were identical to those in the Job treatment; however the description of the source of the money was different. Lotto treatment subjects were told that a relative won a substantial lotto jackpot and offered the following streams of money. The Lotto treatment had 108 subjects and the Job treatment had 104 subjects. Aside from the presence of the Lotto treatment and the absence of the hours questions, the procedure is identical to that in Study 1.

4.2 Data

We note that 209 out of the 212 subjects offered a descriptive rating in a monotonic fashion. We also do not observe a difference between the choices of the subjects presented with the response items in ascending order and descending order. Additionally, we do not observe a relationship between choice and the order of the questions.

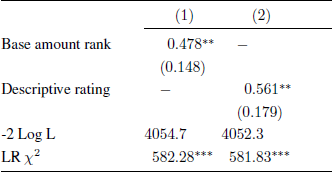

As in Study 1, two repeated-measures regressions examine the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. The first regression examines the relationship between the choice of income stream and the base amount rank of the question. The second regression examines the relationship between the income choice and the subject’s descriptive rating of the base amount corresponding to that question. The variables were coded as in the analysis summarized in Table 3. As we have 212 subjects who each made 5 income choices, both regressions have 1060 observations. See Table 4 for a summary of the regression results.

Table 4: Results of repeated measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Study 2).

Note: unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.001

** p<0.01

As can be seen in Table 4, both regression specifications suggest a positive relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. Using a repeated measures ANOVA, the within-subject factor was F(1,210) = 169.56, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.447, where the degrees of freedom were adjusted for sphericity using the lower bound approach.

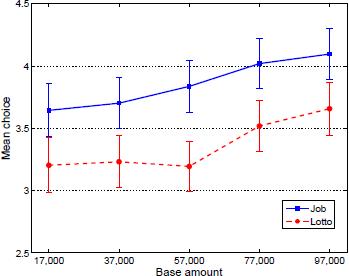

We now compare the Lotto and Job treatments. Figure 1 displays the mean choice by base amount and treatment.

Figure 1: Mean preference for increasing payments by base amount and treatment.

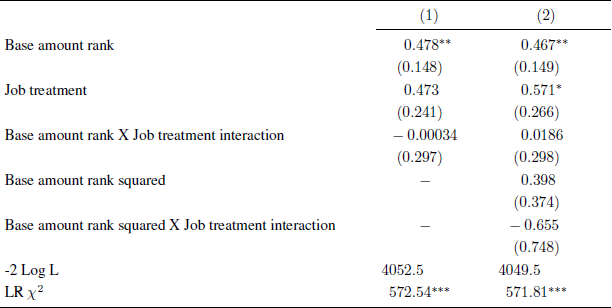

We perform two repeated-measures regressions. As above, the income choice is the

dependent variable and the base amount rank is an independent variable. Also in

both regressions we include the Job treatment and the interaction between Job

treatment and base amount rank as independent variables. The base amount rank is

coded as above. We coded the Job treatment variable as ½ in the Job

treatment and ![]() otherwise. In the second

regression, we also include a base amount rank squared term and the interaction

between the base amount rank squared term and the Job Treatment variable. Table 5 summarizes this analysis.

otherwise. In the second

regression, we also include a base amount rank squared term and the interaction

between the base amount rank squared term and the Job Treatment variable. Table 5 summarizes this analysis.

Table 5: Results of additional repeated-measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Study 2).

Unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.001

** p<0.01

* p<0.05

We note that the base amount rank coefficient is significant in both regressions. However, we note that the treatment variable is significant only in regression (2). We also note that the base amount rank-treatment interaction, the base amount rank squared and the base amount rank squared-treatment interaction variables are not significant. And regression (2) is not sensitive to the specification of the nonlinear term. Rather than employing the base amount rank squared term, specifications involving (1) a term based on the absolute difference from the middle base amount rank, or (2) a term comparing the middle base amount rank to the other four, are qualitatively similar to that summarized in regression (2). Footnote 16

However, we find weak evidence in support of Reference SmithSmith (2009a) by performing a simple effects analysis on a repeated-measures regression of payment choice. In this analysis, the Lotto treatment and Job treatment differ significantly for intermediate payments—specifically for the question with the base amount of $57,000 (F(1,210) = 4.88, p = 0.028)—but the treatments do not differ for large or small payments.

4.3 Discussion

Roughly, Reference SmithSmith (2009a) predicts that, for a decision maker with an imperfect recall of the experienced cost of effort, increasing payments for wage income can reduce the perceived cost of effort. For payments that are very likely or very unlikely to cover the cost of effort, the benefit of such a reduction is minimal. However, for payments that are neither likely nor unlikely to cover the cost of effort, there could be a significant benefit from such a reduction. Therefore, Reference SmithSmith (2009a) predicts that the difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments will be largest for intermediate amounts. Although we do not find strong evidence of this prediction, the simple effects analysis provides weak evidence of this prediction.

It is important to note that Reference SmithSmith (2009a) assumes that the subject does not have a preference for increasing nonwage payments. In other words, in Reference SmithSmith (2009a) the preference for increasing payments emerges exclusively as a result of the mechanism described above. Within the context of Figure 1, this assumption would imply that the Lotto choice would be constant at 1 for each income question. This assumption was made because there was no available data concerning the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. Additionally, it is in this setting that the mechanism of the difference in the preference for wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments could best be observed.

Also note that Reference SmithSmith (2009a) does not predict the nonlinear nature of the Lotto treatment observed in Figure 1 and that this nonlinearity seems to be responsible for the weak evidence that we do find. We postpone a discussion of this matter until the Discussion of the Nonlinearities section following Study 4.

Similar to Study 1, in Study 2 we observe a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. However, we have yet to explore the potential reasons for this relationship. One possible explanation for this relationship is that it is due to decreasing marginal utility of money. We explore this conjecture in the following study.

5 Study 3

5.1 Procedure

A total of 230 Rutgers-Camden law students completed our survey.Footnote 17 The items were administered online via Surveymonkey.com. An email invitation was sent to each law student. The subjects were told that, upon completion of the survey, they would be entered into a lottery for a $50 prize, where one prize would be given for every 50 subjects who completed the survey.Footnote 18

Somewhat peculiar to the field, the post-law-school job market is characterized by two distinct employment options that involve very different sets of attributes.Footnote 19 In our survey, we refer to these options as “Big Firm” and “Small Firm/Public Interest”. When compared to the latter, the former is characterized by longer hours, higher pay, and less control over caseload. In order to manage these heterogenous career expectations, in the first item of the survey, the subjects were asked for their plans after law school: Definitely Big Firm, Probably Big Firm, Possibly Big Firm, I Don’t Know, Possibly Small Firm/Public Interest, Probably Small Firm/Public Interest, or Definitely Small Firm/Public Interest. This initial item would allow the subject to be directed to the appropriate income questions and job description.

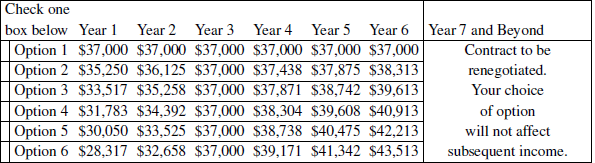

As in both Study 1 and 2, each income question offered subjects 6 options regarding possible income streams. Within each question, the undiscounted sum of the payments of the response items were identical. However, we varied the rate of increase, and hence the present discounted value. As is standard in the legal profession, we offered the payments over 7 years. We told the subjects that, at the end of the seventh year, they will either be fired or promoted; hence their choice would not affect their income after the seventh year.

In an effort to hold the perceived cost of effort constant, while we varied income levels, we provided an employment description for both the Big Firm subjects and the Small Firm/Public Interest subjects. The Small Firm subjects were told, “You work 50 hours per week or less. You have control over your caseload. The job is relatively stress-free and you have a good work-life balance.” For the Small Firm subjects, we presented questions with base amounts of $28,000, $48,000, $68,000, $88,000, $108,000, and $128,000. The Big Firm subjects were told, “You work an excess of 80 hours per week. You have no control over your caseload. The job is relatively stressful and you do not have a good work-life balance.” We presented questions with base amounts of $58,000, $88,000, $118,000, $148,000, $178,000, and $208,000. These amounts within the treatments were selected so that the payments would range from very low to very high, according to the stated career plans of the subjects.

We randomlyFootnote 20 determined whether the income questions were asked in an increasing or decreasing order. Within each question, the response items were automatically randomized by the survey tool. The subjects were then asked to provide their descriptive rating of the relevant starting salaries on a scale of 1 (very low) to 7 (very high).

Next, the subjects were presented with a modified Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman (2008) measure of risk aversion. The item was posed as a choice of bonus structure, whereby the subject could not control the likelihood of obtaining the bonus, and the choice would not affect future payments. The six choices for the Small Firm subjects were, Option 1: $70,000 for sure, Option 2: $68,000 with 50% and $74,000 with 50%, Option 3: $64,000 with 50% and $82,000 with 50%, Option 4: $60,000 with 50% and $90,000 with 50%, Option 5: $54,000 with 50% and $102,000 with 50%, and Option 6: $44,000 with 50% and $122,000 with 50%. The Big Firm subjects were presented with the identical options, with the exception that each monetary amount was multiplied by 2. As in the original Eckel and Grossman measure, the response items were increasing in both risk and expected value. Further, a choice among the options provides a measure of the decreasing marginal utility of money. The measure is the rank of the riskiness of the choice, which ranges from 1 to 6. Here 1 is the most risk averse choice and 6 is the least risk averse choice. We note that the subjects were not presented with the labels of the bonus options, and the survey tool randomized the order of their appearance. Finally, the subjects were offered the hours questions as in Study 1, with the exception that the required hours were specified over 7, rather than 6, years.

5.2 Data

We note that 229 out of the 230 subjects offered a descriptive rating in a monotonic fashion. On the basis of the initial question, 83 subjects were directed to the Big Firm questions and 147 subjects were directed to the Small Firm/Public Interest questions.Footnote 21

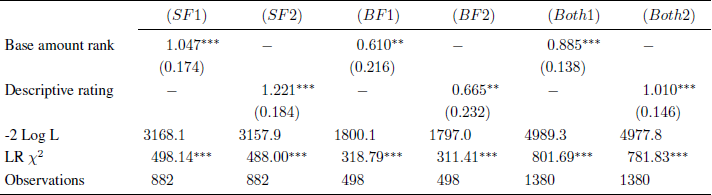

As in the two previous studies, the preference for increasing payments is

positively related to the size of the payments. We run several regressions with

the income choice as the dependent variable. Similar to the previous analysis,

we employ both the base amount rank and the subject’s descriptive rating

as independent variables. Since there are six elements in the base amount rank,

we code the variable as ![]() . The descriptive rating is

coded as in previous analyses. Additionally, we employ a repeated-measures

regression. As there are possible differences between the subjects who select

the Small Firm/Public Interest career over the Big Firm career, we perform the

following analysis. In the regressions labeled SF, we include

only the Small Firm/Public Interest subjects, where each regression has 882

observations. In the regressions labeled BF, we include only

the Big Firm subjects, where each regression has 498 observations. In the

regressions labeled Both, we pool the subjects. In these pooled regressions we

have 1380 observations.Table 6 shows

these regression results.

. The descriptive rating is

coded as in previous analyses. Additionally, we employ a repeated-measures

regression. As there are possible differences between the subjects who select

the Small Firm/Public Interest career over the Big Firm career, we perform the

following analysis. In the regressions labeled SF, we include

only the Small Firm/Public Interest subjects, where each regression has 882

observations. In the regressions labeled BF, we include only

the Big Firm subjects, where each regression has 498 observations. In the

regressions labeled Both, we pool the subjects. In these pooled regressions we

have 1380 observations.Table 6 shows

these regression results.

Table 6: Results of repeated-measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Study 3).

Unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.001

** p<0.01

SF = Small Firm/Public Interest, BF = Big Firm.

As the results ofTable 6 demonstrate, the preference for increasing payments is positively related to the size of the income payments. The results also demonstrate that the preference for increasing payments is positively related to the descriptive rating. This continues to hold when we restrict attention to the category of career plans and when we do not.

Similar to Study 1, we elicit preferences over sequences of income and sequences of hours. Therefore, as in Study 1, we are able to explore whether subjects who exhibit a preference for increasing payments also exhibit a preference for decreasing hours. As in Study 1, we measure the preference for increasing payments by taking the average of the income responses and we measure the preference for decreasing hours by taking the average of the hours responses. Again, a negative correlation would suggest that the subjects exhibit a preference for improving sequences across domains. However, we do not find a significant correlation between these two variables, r(228) = −0.052, p = 0.43.Footnote 22

Also similar to Study 1, we measure the relationship between changes in the preference for increasing wages and changes in the preference for decreasing hours. As above, we calculate the coefficient estimate from a separate linear regression for each subject, with the income choice as the dependent variable and base amount rank as the independent variable. We also calculate the coefficient estimate from a separate linear regression for each subject, with the hours choice as the dependent variable and the rank of the hours question as the independent variable. Again, a negative correlation would suggest that the subjects exhibit changes in the preference for improving sequences across these domains. However, we do not find evidence that these two variables are correlated, r(228) = 0.0082, p = 0.90.Footnote 23

Additionally, we are able to determine whether the preference for increasing payments is related to our measure of marginal utility. Therefore, we examine the relationship between the estimated slope for base amount rank and the response to the bonus question. We note that the marginal utility explanation would suggest a negative correlation between the variables. However, we do not find a significant correlation, r(228) = −0.101, p = 0.13.Footnote 24

Note that, in the analysis above, none of the variables reach even the 0.10 level of significance. The only variable approaching significance is the response to the bonus question, with a p-value of 0.13. Therefore, we do not find evidence that decreasing marginal utility is associated with the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. Also, similar to Study 1, we do not find evidence of a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the preference for decreasing hours.

5.3 Discussion

As in Studies 1 and 2, we find that there is a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. This result is robust to the career plans of the subjects.

A possible explanation for this relationship is that people tend to exhibit a decreasing marginal utility of money. However, for this explanation to hold, the relationship must vary with the degree of decreasing marginal utility. Using a technique adapted from Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman (2008), we took a measure of the decreasing marginal utility of the subject. We find no evidence in support of the decreasing marginal utility explanation. Similar to Study 1, Study 3 does not find evidence of a relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the preference for decreasing hours as a function of the base amounts.

In Studies 1, 2, and 3 the preference for increasing payments is increasing in the size of the payments. In each of these studies, the sequences were constructed by multiplying the base amounts by fixed proportions. This proportional means of constructing the sequences implies that the sequences in the questions involving a larger base amount will be increasing by larger amounts than the sequences in the questions involving a smaller base amount. As such, it remains a possibility that, if fixed values were added to the base amounts, the effect might no longer hold. In order to address this issue, we run the following study.

6 Study 4

6.1 Procedure

A total of 166 undergraduate and graduate students in the psychology subject pool at Rutgers University-Camden were recruited to participate in the experiment. The subjects were given course credit for participating.

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two treatments: the Proportional treatment or the Additive treatment. Subjects in the Proportional treatment were given the identical 5 income amounts that were used in Studies 1 and 2. In the Additive treatment, the sequences were constructed by adding fixed values to the base amounts. The amounts were selected so that the question with a base amount of $57,000 would appear to be similar across treatments. The Additive treatment had 93 subjects and the Proportional treatment had 73 subjects.Footnote 25

We also note the slight changes in the format of the questions that were given to subjects in both treatments.Footnote 26 First, rather than as in previous studies, the payments after the sixth year are represented by a single box, which reads, “Contract to be renegotiated. Your choice of option will not affect subsequent income.” Also, rather than circling their chosen option, we directed subjects to check the corresponding box. With the exceptions described above, the procedures are identical to that in Study 1.

6.2 Data

We note that 164 out of the 166 subjects offered the descriptive ratings in a monotonic fashion. We also find no difference between the choices of the subjects presented with the response items in ascending order and descending order.

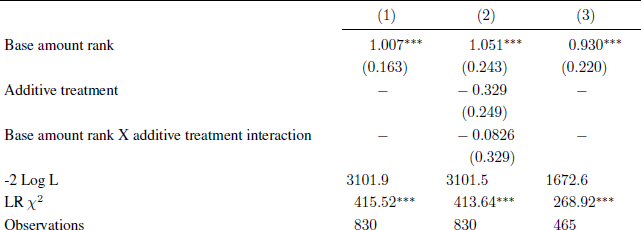

Now we investigate the extent to which our previous results are affected by the form, Additive or Proportional, of the sequences. Below, we run three repeated-measures linear regressions with the degree of the preference for increasing payments as the dependent variable. Each regression also uses the base amount rank of the question as the independent variable. Here we code the base amount rank as in the analyses of Studies 1 and 2. In regression (2) we also employ an additive treatment variable. We code this variable so that it assumes a value of 0.5 in the Additive treatment, and −0.5 otherwise. Also, in regression (2) we include an interaction between the base amount rank and the additive variable. As we have 166 subjects who each made 5 income choices, regressions (1) and (2) both have 830 observations. However, in regression (3) we restrict attention to the subjects who were in the Additive treatment. Regression (3) has 93 subjects who each made 5 income choices and therefore we have 465 observations. SeeTable 7 for a summary of the regressions.

Table 7: Results of repeated-measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Study 4).

Unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.001

Table 7 suggests that the preference for increasing payments is increasing in the size of the payments. In each of the three regressions, the coefficient estimate of the base amount rank is significant and positive. Also, in regression (2) we do not find aggregate differences between the two treatments and treatment does not significantly moderate the effect of base amount rank. Finally, regression (3) exclusively analyzes the subjects in the additive treatment and yields a similar estimate to the pooled data in regression (1).

6.3 Discussion

We find that the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments is robust. In each of the four above studies, we find that the preference for increasing payments is increasing in the size of the payments. Additionally, in Study 4 we do not find evidence that the subjects behave differently when the sequences are constructed by the proportional or additive technique.

7 Discussion of the nonlinearities

In interpreting the weak evidence in support of Reference SmithSmith (2009a), it will also be productive to compare the data obtained from the Job treatment in Study 2 with the data obtained in the other studies. Recall that Study 2 found weak evidence that the difference between the Lotto treatment and Job treatment was largest for intermediate values. Also recall that the difference between the treatments seemed to be due to the nonlinear Lotto treatment rather than the curvature of the Job treatment, which was roughly linear. We now examine whether other income data exhibits such a linear relationship or whether the other data suggests an increasing and concave relationship.

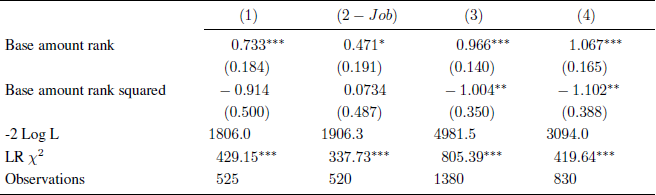

Below, we run four repeated-measures regressions, one for each study, with the degree of the preference for increasing payments as the dependent variable. Each regression uses the base amount rank and the square of the base amount rank as the independent variables. In regression (1) we analyze the data from Study 1. In regression (2 − Job) we analyze the data from the Job treatment in Study 2. In regressions (3) and (4) we analyze the data from Studies 3 and 4, respectively. The variables are coded as in the previous analyses.Table 8 presents the summary of this analysis.

Table 8: Results of additional repeated-measures regressions for predicting strength of preference for increasing income sequences (Studies 1-4).

Unstandardized coefficient estimates with standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.001

** p<0.01

* p<0.05

First we note that (2 − Job) regression is qualitatively different from the other regressions. Regression (2 − Job) is the only regression in which the linear term is not significant at 0.001 and the only one with a positive estimate of the quadratic term. Second, the other regressions are consistent with a pattern that would be more likely to confirm the predictions of Smith (2009a) than that in the Job treatment of Study 2. We note that regressions (1), (3), and (4) have an estimate of the linear term, which is positive and significant at 0.001. We also note that regressions (1), (3), and (4) each have a negative quadratic estimate. Further, the quadratic estimates in regressions (3) and (4) are significant at 0.01 and although (1) is not significant, it has a p-value of 0.07. This implies that in regressions (1), (3), and (4), choice is increasing in the base amount rank and also concave.

An increasing and concave relationship would be more likely to identify the behavior as predicted by Reference SmithSmith (2009a) than would the income data from Study 2. In addition to the simple effects analysis from Study 2, in our view this contributes to the evidence, albeit weakly, in support of the predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a). Specifically, it seems that if the income data obtained in Study 2 exhibited the qualitative properties of the income data obtained in other settings (increasing and concave) then we would find stronger evidence in support of Reference SmithSmith (2009a). In the end, it seems rather unfortunate that the only study in which we attempted to test the predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a) was also the only study that did not find the concave behavior that we found in the other studies.

8 Conclusion

Prior research has found that people often exhibit a preference for increasing payments. We contribute to the literature by finding evidence that the preference for increasing payments is increasing in the size of the payments. Indeed, we find this in each of our four studies, despite the differences in the subject populations. Additionally, this effect does not appear to be affected by whether the increase is additive or proportional.

The available evidence does not support the decreasing marginal utility explanation of the effect of size on the preference for increasing payments. A measure of decreasing marginal utility was not associated with the relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the size of the payments. Also, we find no relationship between the preference for increasing payments and the preference for improving nonmonetary sequences.

Finally, we find weak experimental evidence supporting the theoretical predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a). The difference between the preference for increasing wage payments and the preference for increasing nonwage payments appears to be largest for intermediate values.

It is worth reflecting on the limitations of the present study. First, before we completely rule out the marginal utility explanation, we note that our evidence is clearly affected by our choice of the measure of decreasing marginal utility. Perhaps behavior in our adaptation of the Reference Eckel and GrossmanEckel and Grossman (2008) measure is not reliable for the large payment amounts that we employ. Although we are not aware of a more attractive alternative, it is possible that this measure of risk aversion does not adequately measure the decreasing marginal utility of the subject. We hope that future work will examine the marginal utility explanation. Second, we hope that future work will be able to further examine the predictions of Reference SmithSmith (2009a). Although we found weak evidence in support of these predictions, in our view, the evidence would be stronger had we observed in Study 2, as we did in the other studies, an increasing and concave relationship involving wages. Third, choice in our experiments is not incentivized.

Appendix

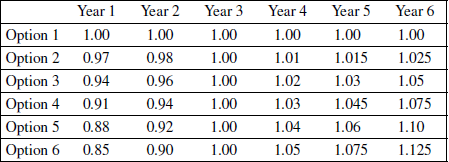

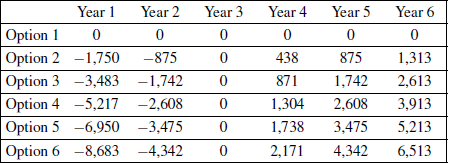

In Studies 1, 2, and the Proportional treatment in Study 4 we constructed the income sequence questions are follows. Each question consisted of multiplying one of the base amounts of $17,000, $37,000, $57,000, $77,000, and $97,000 to the values in the table below.

The sequences in Study 3 were constructed in a similar proportional fashion. In the Additive treatment in Study 4 we added the following values to the base amount, regardless of the question.

Sample income question from Study 1

To better understand your preferences for your future career, we will ask a series of questions.

There are no correct answers, so please answer as honestly as possible.

You are reasonable happy with the nonmonetary aspects of the job and you are offered the following payment schedules over the next 6 years.

Specifically, you are given 6 options (Option 1,…, Option 6) which specifies an amount of income for each of the following 6 years.

At the end of 6 years, you will either be promoted to a higher position or you will be fired. Therefore your choice of payment will have no bearing on your income at the end of the six years.

**Note all amounts are listed in 2009 dollars therefore your answer should not reflect your beliefs about future inflation.

Sample hours question from Study 1

Consider another job with the same 6 year structure. Suppose that your employer allows you to allocate your time commitment among the 6 years. Your choice will not affect your promotion or your salary.

Which do you prefer? (Select one)

The hours questions in Study 3 were constructed in a similar fashion.

Sample Small Firm/Public Interest income question from Study 3.

Consider employment in a small law firm with the following characteristics: You work 50 hours per week or less. You have control over your caseload. The job is relatively stress-free and you have a good work-life balance.

Consider the following payment options which specify payment in the first through seventh years.

As the end of 7 years, you will either be promoted to partner or you will be fired. Your choice of payment structure will have no bearing on your income at the end of the 7 years and should not factor into your answer.

**Note all amounts are listed in 2009 dollars therefore your answer should not reflect your beliefs about future inflation.

Sample income question from Study 4

Imagine that you have just started a job which you expect to enjoy and that you plan on keeping for many years.

The company gives you 6 different options for payment over your first 6 years. Specifically, you are given 6 options (Option 1,… , Option 6) each of which specifies an amount of income for each of the following 6 years.

At the end of 6 years, your contract will be negotiated and your choice of payment option will have no effect on your income at the end of the six years.

Select exactly one of the six payment options you most prefer.

There are no correct answers, so please answer as honestly as possible.

** Note all amounts are listed in 2012 dollars therefore your answer should not reflect your beliefs about future inflation.