LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading the article you will be able to:

• understand the role of the Court of Protection 2017 rules on expert witnesses and professionals providing evidence to the Court of Protection

• understand the impact of the Court of Protection judgment in AMDC v AG & Anor [2013] on the role of expert witness and professional reports

• appreciate how previous case law influences and shapes Court of Protection decisions and judgments.

This article reviews a Court of Protection (COP) judgment from November 2020 – AMDC v AG & Anor [2013]. In many respects this was a routine case for the court whereby it was asked to determine a variety of capacity-based decisions of a 68-year-old woman with a form of dementia. However, owing to issues and concerns with the expert witness evidence presented, the court was minded to review the role of such witness evidence. In doing so, a learning outcome for clinicians was that the judgment provided helpful advice on how expert witness reports, and similar professional reports, should be attained and constructed under the Court of Protection Rules 2017 (COPR: www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/1035/contents/made). Together with pertinent advice from previous case law regarding capacity assessments under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), meaningful and practicable guidance is elucidated for clinicians providing expert witness reports and also professional reports to the COP under section 49 of the MCA (section 49 reports).

Court of Protection Rules 2017 – Part 15 (‘Experts’)

The Court of Protection was established by the Mental Capacity Act 2005. It has jurisdiction over decisions involving property, financial affairs, personal welfare and healthcare for people who lack capacity to make decisions for themselves. The court applies an inquisitorial system, i.e. it is actively involved in establishing the facts of a case (as distinct from an adversarial approach used by other courts, where the primary role is that of an impartial referee between prosecution and defence within a case).

The COPR are a consolidated set of rules governing the practice and procedure in the COP – the current rules from 2017 have updated those from their inception in 2007. Part 15 of the COPR (often referred to as ‘rule 15’ or ‘r15’) is entitled ‘Experts’. It contains all the rules applying to instructing experts and the COP powers in relation to expert witness evidence.

The COPR are supported by Practice Direction 15A – Expert evidence (www.judiciary.gov.uk/publications/15a-expert-evidence/). This supplements Part 15 and provides general requirements for expert evidence and the form and content of submitted reports. All expert witnesses, and those instructing them, are expected to abide by both the COPR rule 15 and Practice Direction 15A. The 2013 judgment noted that expert evidence under COPR rule 15 was not the only way in which capacity assessments can be provided to the court. Rule 15.3(2) permits the court to ‘file or adduce expert evidence’ if satisfied that (a) it is necessary to assist the court to resolve the issues in the proceedings and (b) it cannot otherwise be provided either by a rule 1.2 accredited legal representative or in a report under section 49 of the MCA (‘Power to call for reports’ – see below).

In a helpful COP user's guide, Wills-Goldingham et al (Reference Wills-Goldingham, Leslie and Divall2018) review the role of an expert witness. They note that there is no formal definition of ‘expert’ found within the COPR but given the ‘ethos’ of the COP and the ‘inclusiveness’ of those needed to aid the COP to make decisions in the best interests of the person involved, it can be assumed that an expert has the same meaning as in other jurisdictions – an expert witness is an expert whose evidence is relevant to the case being tried by the court or tribunal and whose evidence is admitted by the court or tribunal (Rix Reference Rix2011). Rix et al (Reference Rix, Haycroft and Eastman2017a), in noting there is no statutory definition in English law overall as to who is an expert, provide helpful pointers as to a possible definition from various global sources. The expert has an ‘overriding duty’ to the COP to help in matters that fall within their expertise. Where possible, the parties involved in a case are expected to have had discussions as to whether expert evidence is required and if so from whom. The norm is for a ‘single joint expert’ to be appointed and it is very rare for the COP to sanction more than one expert, i.e. one expert is agreed upon and instructed by all parties, with the costs being shared between all parties. Cases will predictably vary contextually from case to case, and hence the types of expert needed will concomitantly vary, for example psychiatrists, psychologists, independent social workers, occupational therapists, financial advisors, surveyors; for medical cases specialists from a particular medical specialty/subspecialty may be indicated. In general though, health and welfare cases will need expert psychiatric or psychological evidence to decide whether the person does or does not have capacity for the decisions in question under the MCA, i.e. if the person is assessed as having capacity to make a specific decision then of course the COP has no further jurisdiction to make best interests decisions in that matter.

Why the case came to court

The person involved in this case was a 68-year-old woman known as ‘AG’, who resided at the E Care Home (‘ECH’). The applicant was the local authority that brought the case to court. It was responsible for meeting AG's eligible care and support needs under the Care Act 2014 and had commissioned her placement at ECH. The issues to be determined by the court were whether, as the local authority contended, AG lacked capacity to make decisions in relation to:

(a) the conduct of litigation

(b) her place of residence

(c) her care and support

(d) her contact with other people

(e) management of her property and affairs, including termination of her tenancy

(f) engagement in sexual relations

(g) marriage.

There was another respondent, ‘CI’, who was a male resident at the care home with whom AG had ‘formed an attachment’. All parties to the case had legal representatives.

The court process began in January 2020, with the final hearing occurring in October 2020. Following the case originally coming before the court there were subsequent hearings, interim orders and directions given by the court. These included the joint instruction by all the parties involved of an expert witness, Dr X, a consultant forensic psychiatrist.

Background to the case

The judgment did not provide much narrative about AG herself, but did describe her as having previously been married four times (the court was told she was still married) and she had four children, eleven grandchildren and eighteen great grandchildren. Previously she had been living alone as a local authority tenant in a bungalow. AG had an existing diagnosis of frontal lobe dementia which was associated with behavioural changes including periods of confusion and aggression. It was alleged that she had become a frequent caller to the ambulance service and a frequent attender at the hospital accident and emergency department, where she was assessed as not needing any medical intervention (on one day alone in December 2018 she was noted to have called the ambulance service on 16 occasions). Even with intensive support from Age UK for around 3 years, AG was noted to frequently run out of money, on one occasion she was found naked wandering outside her home, on several occasions she had lost her belongings, including her keys, handbag, passport, bank cards or money. She had also smashed her neighbours’ plant pots. The local authority contended that even with support, AG's behaviour affected her ability to live safely in the community on her own. An incident in July 2019 culminated in her being moved into ECH on an emergency respite basis, where she continued to live at the time of the court case. The court noted that AG did not accept that she needed admission to ECH and was there under a deprivation of liberty order.

The judgment described the relationship AG had developed with another resident, known as CI, who had moved into ECH in November 2019. CI relied on a wheelchair as a result of a stroke but was described as being still cognitively intact. AG and CI developed a relationship such that they were found ‘sharing intimacy’ on several occasions. CI disclosed to his social worker that they had taken their relationship ‘to the next level’ and that they wanted to marry and live together. In light of this, in mid-December 2019 AG was reviewed by her social worker and assessed as lacking capacity to consent to sexual relations. Following this assessment, AG and CI were found together in CI's bed on further occasions.

Application of the MCA

As with all Court of Protection cases the MCA is systematically applied and analysed. The judgment in this case particularly noted that section 1 (‘The principles’) and section 3 (‘Inability to make decisions’) were particularly apposite to the issues arising in this case. The judgment also drew on recent MCA jurisprudence from another COP case, London Borough of Tower Hamlets v PB [2020], which eloquently described ‘helpful guidance’ as to the general approach to be taken by the court when determining capacity issues (Box 1). In that case the court assessed whether a 52-year-old man with a history of alcohol dependency and alcohol-related brain damage, dissocial personality disorder and physical health problems such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hepatitis C and HIV, had capacity to make decisions about the care he received and where he lived. The judgment in this case concurred with this guidance in that when assessing the capacity of an individual, ‘to set the bar too high could be unfair, unnecessary and discriminatory against the mentally disabled’. Such a principle was underpinned by further jurisprudence cited from the High Court: Sheffield City Council v E [2004] and PH v A Local Authority [2011]. A further ‘linked principle’ emanating from LBL v RYJ [2010] was also applicable in this case, in that a person must understand the salient information but not necessarily all the peripheral detail around a decision under the MCA.

BOX 1 Guidance for a general approach when determining capacity issues under the MCA

a. The obligation of this Court to protect P is not confined to physical, emotional or medical welfare, it extends in all cases and at all times to the protection of P's autonomy;

b. The healthy and moral human instinct to protect vulnerable people from unwise, indeed, potentially catastrophic decisions must never be permitted to eclipse their fundamental right to take their own decisions where they have the capacity to do so. Misguided paternalism has no place in the Court of Protection;

c. Whatever factual similarities may arise in the case law, the Court will always be concerned to evaluate the particular decision faced by the individual (P) in every case. The framework of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 establishes a uniquely fact sensitive jurisdiction;

d. The presumption of capacity is the paramount principle in the MCA. It can only be displaced by cogent and well-reasoned analysis;

e. The criteria for assessing capacity should be established on a realistic evaluation of what is required to understand the ambit of a particular decision by the individual in focus. The bar should never be set unnecessarily high. The criteria by which capacity is evaluated on any particular issue should not be confined within artificial or conceptual silos but applied in a way which is sensitive to the particular circumstances of the case and the individual involved, see London Borough of Tower Hamlets v NB (consent to sex) [2019]. The professional instinct to achieve that which is objectively in P's best interests should never influence the formulation of the criteria on which capacity is assessed;

f. It follows from the above that the weight to be given to P's expressed wishes and feelings will inevitably vary from case to case.’

The expert evidence

Dr X saw AG in person on three occasions at ECH (including during the COVID-19 pandemic period) in February, May and September 2020, producing reports after each assessment. He also produced another report in August 2020 in response to a further assessment by the allocated social worker and further questions from the parties.

His first report in February concluded that AG lacked capacity in all decisions being assessed. Following this initial report, Dr X was asked to assess additional capacity decisions for marriage and for issuing a divorce petition. The judgment explained that the letter of instruction had been clear that the parties involved wished Dr X to give more detail and explanation for his views on capacity; more specifically, for each decision that he assessed, it asked that Dr X set out what information was given to AG and what her ability had been to understand, retain, use or weigh that information (i.e. section 3(1) of the MCA). Dr X concluded in his June report (on the May assessment) that AG did have capacity to make decisions about marrying and issuing divorce proceedings. In oral evidence in court Dr X explained that at that time he had concluded that AG had fluctuating capacity in relation to all decisions being assessed (save for the decisions to marry and issue divorce proceedings). Dr X explained and emphasised that he had considered the impact of periods of disinhibition on AG's ability to use or weigh relevant information. At that time he had also flagged up the possibility of AG's dementia process deteriorating.

Following the June report, the parties asked Dr X to consider the relevance of a Court of Appeal decision (A Local Authority v JB [2020]) from the same month to the question of whether AG had capacity to make decisions about engaging in sexual relations (this being a contextually different question from that of capacity to consent to sexual relations, which was addressed in Dr X's first report). In a report provided in August, Dr X concluded that it was ‘probable’ that the clinical picture had changed from previous assessments in that there was a more obvious global cognitive deterioration and, contrary to what he had initially opined in his first report, the cognitive impairment was likely to now be on a continuous basis as opposed to being fluctuating.

Dr X noted that he found AG's condition to have significantly deteriorated in the intervening months when he assessed her in September, having been asked to do so again by the court following requests by the parties. Initially on seeing him, AG did not recall having met him previously. She could not understand the nature and purpose of Dr X seeing her again despite him explaining this in basic language on several occasions. Dr X described how he attempted to explore the areas of decision-making and capacity under consideration but AG's responses ‘lacked any meaningful detail’, for example she replied ‘no idea’ to questioning about financial arrangements, and when asked about sexual relations AG replied that she and CI would look after one another but she would not tolerate any further enquiry. From this assessment Dr X concluded that ‘her superficiality, fatuous presentation and irritability’ when he tried to explore relevant issues likely arose owing to a decline in her cognitive functioning. He concluded that AG lacked capacity to make decisions about her residence, her care and support, her contact with others, her property and affairs, and whether to engage in sexual relations. Despite AG's cognitive decline, Dr X maintained his views from June on her capacity to marry and to issue divorce proceedings because he had not re-addressed them at the assessment in September. This ‘did not sit well’ with the court, given his final assessment that AG lacked capacity to decide whether to engage in sexual relations.

Difficulties with the expert evidence

The court noted that despite Dr X's previous experience in providing expert evidence to the COP on many occasions, this was a case that clearly ‘troubled’ Dr X. Unfortunately in this case his evidence had left the parties, the court and even Dr X himself with ‘some disquiet’. The judge emphasised he had no ‘misgivings about Dr X's professionalism or expertise’ and that no one had questioned his conduct. In court he had responded ‘very properly’ to questioning and had not sought to ‘gloss over concerns raised’. The concerns expressed by the parties in this case, shared by the court, arose from the written reports provided by the expert witness.

The parties had concerns about the written evidence, but there was little time to consider the final report prior to the hearing, and hence the extent of their concerns did not fully emerge until oral evidence was heard. The applicant explained that it did not consider that it ‘could adduce sufficient evidence in relation to capacity’ to found declarations to that effect under section 15 of the MCA (‘Power to make declarations’). In light of this, the applicant did not concede that AG had capacity in relation to any of the decisions being assessed because it considered it could not rely on Dr X's evidence to prove that AG lacked capacity. Furthermore, the applicant felt that there was ‘insufficient evidence to do so’, bearing in mind that such views of the expert witness were ‘crucial to the determinations of capacity’ that the court was assessing in this case. The court concurred that the expert assessments did not fully address all of the decisions in question regarding AG's capacity (this despite detailed letters of instruction complying with Practice Direction 15A having been sent prior to each assessment setting out the relevant information pertaining to each decision and at times seeking more clarification and explanation of his views). Overall, what concerned the interested parties was the process that led Dr X to his conclusions and the lack of ‘clear explanation’ as to how conclusions had been reached. There was no dispute between all parties that, owing to AG's frontal lobe dementia, the ‘diagnostic element’ of the test for incapacity (section 2(1) of the MCA) was satisfied. Where the parties differed was in being unable to agree that the ‘functional element’ (section 3(1)) was satisfied or that the presumption of capacity was rebutted or disproved (section 1(2)) on the evidence presented. Such concerns were directly addressed with Dr X at the court hearing (Box 2).

BOX 2 Concerns emanating from the expert evidence in 2013

a. Paragraph 4.16 of the Code of Practice states, ‘It is important not to assess someone's understanding before they have been given relevant information about a decision. Every effort must be made to provide information in a way that is most appropriate to help the person understand’. The expert's reports did not provide sufficient evidence either that AG had been given the relevant information in relation to each decision, or of the discussions the expert had had with P about the relevant information.

b. It is not a criticism of an expert that at different times they have reached different conclusions about a person's capacity. Capacity can change and new evidence may come to light. However, in this case significantly different conclusions had been reached at different times without clear explanations of why the conclusions had changed or how the evidence as a whole fitted together. Further, the change in opinion between the June report and the August letter had followed the receipt of a single further statement and without any further face to face assessment.

c. The expert's final conclusion had been reached on a broad-brush basis rather than by reference to each decision under consideration.

d. A lack of information to show how AG had been assisted to engage when the expert had ‘hit a brick wall’ in his attempts to have a discussion with her at his final interview. The lack of information left doubt as to whether AG was incapable of understanding the purpose of the interview, whether she had been given adequate support to engage, or whether she had simply chosen not to talk to the expert.

e. A lack of a cogent explanation for why the presumption of capacity had been displaced in relation to the decisions under consideration. Conclusions were stated but not clearly explained.’

Outcome of the case

Owing to concerns about the evidence presented, the judge adjourned the case. He felt that the hearing was only part heard as the evidence presented was incomplete and he could therefore not make his own overall conclusions. It was not a case in which the application could simply be dismissed for lack of evidence. In adjourning the case, he was satisfied, despite the concerns over the expert evidence, that there was a clear reason to believe that AG did lack capacity to make the various decisions under consideration, and hence interim orders and directions under section 48 of the MCA (‘Interim orders and directions’) were made in her best interests. These included:

(a) the judge authorising AG's continued deprivation of liberty at ECH, along with an earlier safeguarding plan in place (in doing so, explicitly acknowledging the interference with AG's rights under Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998 – Right to respect for private and family life – as a result of such interim orders);

(b) ongoing restrictions persisting until the case was fully heard effectively preventing AG from engaging in sexual intercourse, from leaving ECH and from choosing her care arrangements;

(c) scheduling another hearing with evidence to be heard from a new expert psychiatrist.

Although all agreed it was ‘regrettable’, there was a need for a further delay to instruct a new expert to provide reports. The judgment sagely noted that the newly instructed expert may or may not reach the same conclusions as Dr X but it was imperative that the court could see from future expert reports that ‘the fundamental principles of the MCA 2005 have been followed, that proper steps have been taken to support AG's decision-making and participation in the assessment, and that the conclusions reached are adequately explained’.

The adjourned case was heard as planned in January 2021 when a new expert witness provided evidence (A v AG and CI [2021]). The judgment noted that the new expert witness report:

• was very clearly set out

• referred to the detailed instructions received

• recorded the fundamental principles of the MCA

• demonstrated throughout that AG's capacity was assessed in a decision-specific way by referring to relevant information and applying MCA section 3 tests;

• had considered separately the diagnostic and functional tests of capacity and the question of causation

• had quoted questions and answers from his interview with AG (the court noting that such extracts were ‘illuminating’).

In essence, the new expert witness had applied the guidance provided from the previous case (Box 3). The judgment assessed the same capacity-based decisions as before. It found that AG lacked capacity to make decisions about litigation, residence, care, financial affairs and property, and marriage. However, it concluded that AG did have capacity to make decisions about contact with others and engagement in sexual relations. Following this, previous restrictions on AG and CI being able to have any physical intimacy were to be reconsidered and a safeguarding adults protection plan in place would be withdrawn. The care home would then follow the Care Quality Commission's guidance on relationships and sexuality in adult social care services (CQC 2019) and the local authority would consider potential options for AG in terms of accommodation, care and support packages, including the possibility she and CI could reside together. While these issues were considered, AG would remain at ECH under a deprivation of liberty order, which was necessary and proportionate and in her best interests.

BOX 3 Guidance for preparation of reports for the Court of Protection

‘When providing written reports to the court on P's capacity, it will benefit the court if the expert bears in mind the following:

a. An expert report on capacity is not a clinical assessment but should seek to assist the court to determine certain identified issues. The expert should therefore pay close regard to (i) the terms of the Mental Capacity Act and Code of Practice, and (ii) the letter of instruction.

b. The letter of instruction should, as it did in this case, identify the decisions under consideration, the relevant information for each decision, the need to consider the diagnostic and functional elements of capacity, and the causal relationship between any impairment and the inability to decide. It will assist the court if the expert structures their report accordingly. If an expert witness is unsure what decisions they are being asked to consider, what the relevant information is in respect to those decisions, or any other matter relevant to the making of their report, they should ask for clarification.

c. It is important that the parties and the court can see from their reports that the expert has understood and applied the presumption of capacity and the other fundamental principles set out at section 1 of the MCA 2005.

d. In cases where the expert assesses capacity in relation to more than one decision,

i. broad-brush conclusions are unlikely to be as helpful as specific conclusions as to the capacity to make each decision;

ii. experts should ensure that their opinions in relation to each decision are consistent and coherent.

e. An expert report should not only state the expert's opinions, but also explain the basis of each opinion. The court is unlikely to give weight to an opinion unless it knows on what evidence it was based, and what reasoning led to it being formed.

f. If an expert changes their opinion on capacity following re-assessment or otherwise, they ought to provide a full explanation of why their conclusion has changed.

g. The interview with P need not be fully transcribed in the body of the report (although it might be provided in an appendix), but if the expert relies on a particular exchange or something said by P during interview, then at least an account of what was said should be included.

h. If on assessment P does not engage with the expert, then the expert is not required mechanically to ask P about each and every piece of relevant information if to do so would be obviously futile or even aggravating. However, the report should record what attempts were made to assist P to engage and what alternative strategies were used. If an expert hits a ‘brick wall’ with P then they might want to liaise with others to formulate alternative strategies to engage P. The expert might consider what further bespoke education or support can be given to P to promote P's capacity or P's engagement in the decisions which may have to be taken on their behalf. Failure to take steps to assist P to engage and to support her in her decision-making would be contrary to the fundamental principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 ss 1(3) and 3(2).’

Preparation of reports

In light of the issues that had emerged in relation to the expert reports, the judge thought it would be ‘helpful’ to provide ‘some indications’ on how experts’ reports on capacity could best assist the court (Box 3). Although this guidance is quite detailed, the judge did not wish to ‘be prescriptive about the form and content of reports’ – the starting point, he reminded, was that COPR rule 15 and Practice Direction 15A should be followed by all experts and those instructing them. Furthermore, the judge purposefully did not comment on the way an expert should interview or assess a patient, which is of course a matter for the expert's ‘professional judgment’.

Although this guidance was primarily for those submitting rule 15 expert witness reports, the judge opined that it could also be useful for section 49 reports, which comment on capacity-based decisions, written by psychiatrists, social workers or best interests assessors where capacity assessments were ‘no less important’.

Mental Capacity Act – Section 49 (‘Power to call for reports’)

The COPR includes the right to issue directions for section 49 reports (rules 3.7(2)(a), 14.24 and 14.25). These rules are supplemented by further advice contained within Practice Direction 14E (www.judiciary.uk/publications/14e-section-49-reports/). When considering any question relating to someone who may lack capacity, section 49 allows for the COP to order reports from National Health Service (NHS) health bodies, local authorities, the public guardian or a COP visitor (whose role is to provide independent advice to the COP as to whether anyone with power under the MCA is fulfilling their duties and responsibilities). Any nominated NHS health body must find an appropriate professional, invariably a psychiatrist, from their organisation to provide a report (irrespective of whether the person is known or not to their services). The person compiling the report has a duty to provide their views to the court and not to the patient or parties.

Discussion

The key learning points for writing reports for the COP are encapsulated in Box 3. Such guidance is practical and can be implemented by clinicians. Equally, however, it demonstrates the depth and extent of what should be considered when composing such a report, which of course is unavoidably time-consuming. The crux of this case was the vital importance of clearly showing the working out and explanation of any opinions and conclusions arrived at in expert reports. This was essential so as to show the application of the MCA principles and to show that key sections were adhered to to help the court in the matters being assessed. Apart from the relevant practice directions noted above, further information and advice on composing expert and section 49 reports for the COP can be found in a COP user's guide by Wills-Goldingham et al (Reference Wills-Goldingham, Leslie and Divall2018), The Court of Protection Handbook (Ruck Keene Reference Ruck Keene, Edwards and Eldergill2019a), good practice guidelines for expert psychiatric witnesses (Rix Reference Rix, Eastman and Haycroft2017b) and a review on section 49 reports by Griffith (Reference Griffith2018). Another valuable information resource is the website that accompanies The Court of Protection Handbook, which is found at www.courtofprotectionhandbook.com. Some COP judgments will specifically address problematic aspects of applying the MCA and, as in this case, provide practical advice on any thorny issues arising: for example, Royal Borough of Greenwich v CDM [2019] on fluctuating capacity and QJ v A Local Authority & Anor [2020] on ensuring that the starting point of any capacity assessment, the presumption of capacity, is satisfactorily rebutted or disproved. A review of the first 10 years of the COP outlined the development of this specialist court and the history of the functional model of mental capacity (Ruck Keene Reference Ruck Keene, Kane and Kim2019b). It also reviewed in depth 40 published cases of capacity disputes presented to the COP during the same time period. The authors concluded that the work of the COP provided a ‘powerful illustration’ of what taking capacity seriously looked like from inside and outside the courtroom, but that the court was ‘still on a learning curve’, for example it had changed and learned from cases and from cases referred to the Court of Appeal.

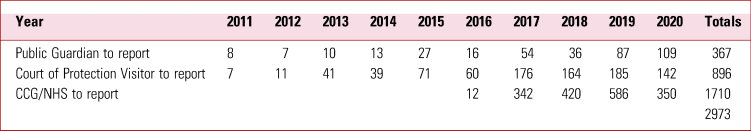

The purpose and requirements for section 49 reports were reviewed by Griffith (Reference Griffith2018), who noted that the number of orders for section 49 report by the COP had increased since a case in 2015 (RS v LCC [2015]), especially from NHS bodies. The steady annual increase in section 49 reports being requested by the COP is evident in data I obtained following a freedom of information request from the Ministry of Justice in February 2021 (Table 1). The 89-year-old woman at the centre of RS was not known to the NHS trust. The trust argued that, because of this, providing a report would place a significant and disproportionate burden on its resources. It suggested that it would be more appropriate for the parties involved to pay for an independent expert witness to write a capacity report on the woman. The COP held that NHS bodies had a duty to provide a report as directed by the court but there was no provision under the MCA that allowed the NHS body to charge a fee for a section 49 report. Consequently, lawyers involved in such cases have taken advantage of the COP being able to obtain specialist information without any additional cost involved. In addition to noting ethical issues for psychiatrists and medico-legal costs having been shifted to the NHS, Mirza & Kripalani (Reference Mirza and Kripalani2019) argue that there is a blurring of boundaries between expert and professional witnesses and consequently a need to clarify what legal safeguards are in place for section 49 report authors were their opinion to be challenged, as happened in the important case of Pool v General Medical Council [2014] (see also Rix et al, Reference Rix, Haycroft and Eastman2017a, which describes this case). The General Medical Council (2013) describes a professional witness as someone giving evidence as a witness of fact, i.e. providing professional evidence of their clinical findings, observations and actions, and the reasons for them. It describes the role of an expert witness as being to help the court on specialist or technical matters that are within the witness's expertise, i.e. they are able to consider all the evidence available, including statements and reports from the other parties to the proceedings, before forming and providing an opinion to the court. Mirza & Kripalani (Reference Mirza and Kripalani2019) note that, with regard to professional implications, section 49 reports require an opinion, but according to both British Medical Association (BMA) and GMC guidance this falls under expert witness work, i.e. a discrepancy currently exists, as what is considered expert witness work by regulatory bodies is being framed as normal NHS work by the COP under the current system. They also contend that there is an urgent need to quantify the effects of increasing numbers of orders for section 49 reports on service and resource provision.

TABLE 1 Annual numbers of section 49 report requests from the Court of Protectiona

CCG, clinical commissioning group; NHS, National Health Service.

a Data obtained from a Ministry of Justice freedom of information request in February 2021.

In providing guidance on report writing, the judgment noted that the ‘inquiry into capacity will vary considerably from case to case’ and that ‘experts must always be sensitive to what is required for the individual assessment in which they are engaged’. In doing so, the judge was mindful of a recent report of the President's Working Group on Medical Experts in the Family Courts (2020). This report highlighted various pressures on expert witnesses and one recommendation was for constructive feedback to encourage good practice. In taking heed of this advice, the judge took ‘due care’ to provide comments intended to ‘merely assist’ experts when writing reports in similar cases such as this for the COP.

Acknowledgement

I thank Claire Bradley, Library Assistant in the Education Centre Library, St Michael's Hospital, for assistance with the freedom of information request and literature search.

Author contribution

This is the sole work of this author.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

An ICMJE form is in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2021.52.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The Court of Protection Rules 2017:

a replaced and revoked the Court of Protection Rules 2005

b are a set of rules governing the practice and procedure in the Court of Protection of the whole of the UK

c are arranged into 20 Parts

d are a set of rules governing the practice and procedure in the Court of Protection in England and Wales

e include powers for reports to be submitted from expert witnesses only.

2 As regards expert witness reports under the Court of Protection Rules 2017:

a Part 13 of the Court of Protection Rules 2017 is entitled ‘Experts and section 49 reports’

b the Court of Protection Rules 2017 are not supported by any practice direction

c Practice Direction 15A supplements Part 15 and provides general requirements for expert evidence and the form and content of submitted reports

d all expert witnesses, and those instructing them, are expected to abide by Practice Direction 15A only

e Part 15 or rule 15 of the Court of Protection Rules 2017 is the only way in which capacity assessments can be provided to the court.

3 Again as regards expert witness reports under the Court of Protection Rules 2017:

a there is a formal definition of ‘expert’ found within the Court of Protection Rules 2017

b the expert has a partial duty to the Court of Protection to help in matters that fall within their expertise

c when an expert witness is needed it is normal to appoint two experts for a case

d expert witness reports can only come from psychiatrists

e expert witness reports may come from surveyors.

4 As regards reports under section 49 of the Mental Capacity Act 2005:

a the person compiling the section 49 report has a duty to provide their views to the court and not to the patient or parties

b the Court of Protection Rules 2017 are not supplemented by further advice contained within Practice Direction 15A

c section 49 of the MCA allows for the Court of Protection to order reports from the public guardian or a Court of Protection visitor only

d an NHS health body need only provide a section 49 report if the person involved is already known to their services

e NHS bodies can charge the Court of Protection for section 49 reports requested.

5 As regards the guidance emanating from London Borough of Tower Hamlets v PB [Reference Ruck Keene, Edwards and Eldergill2020] for a general approach when determining capacity issues under the MCA:

a the obligation of the Court of Protection is to protect P only with regard to their physical and medical welfare

b the presumption of capacity is the paramount principle in the MCA

c the weight given to P's expressed wishes and feelings will not usually vary from case to case

d the bar for criteria for assessing capacity should always be set very high

e whatever factual similarities may arise in the case law, the Court of Protection will only on occasion be concerned to evaluate the particular decision faced by the individual in every case.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 c 3 e 4 a 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.