Introduction

Southern Iran is considered one of the major routes through which hominins repeatedly expanded out of the African continent (Vahdati Nasab et al. Reference Vahdati Nasab, Clark and Torkamandi2013; Groucutt et al. Reference Groucutt2021; Shoaee et al. Reference Shoaee, Vahdati Nasab and Petraglia2021). Given that the Persian Gulf has witnessed repeated changes in dimensions throughout the late Pleistocene (Rose Reference Rose2010; Zadeh & Shafeii Reference Zadeh and Shafeii2021), what is today the Strait of Hormuz (Figure 1) could have been used as a corridor for the dispersal of hominins via the Arabian Peninsula. The strategic geographical position of the surveyed area, coupled with the results of previous sporadic surveys and excavations within the Persian Gulf (e.g. Vita-Finzi & Copeland Reference Vita-Finzi and Copeland1980; Dashtizadeh Reference Dashtizadeh2009; Bretzke et al. Reference Bretzke, Conard and Uerpmann2014, Reference Bretzke, Yousif and Jasim2018), emphasises its importance as a hominin migratory route.

Figure 1. The location of the surveyed area in regard to the Persian Gulf (left), and three clusters of Palaeolithic localities within the Halil Rud river basin and foothills of the Jebel Barez Mountains (right) (map and photograph by A. Anjomrooz and H. Vahdati Nasab).

Methodology

The survey was conducted in 2021 and covers an area located almost 100km north of the Strait of Hormuz, including the foothills of the Jiroft Mountains and the Halil Rud River basin, in the vicinity of Jiroft, Kerman Province, southern Iran (Figure 1). Prior to this survey, the Palaeolithic potential of the area has been demonstrated by a small number of surveys in the adjacent regions (Khodabakhshi Parizi et al. Reference Khodabakhshi Parizi, Mortazavi and Mosapour Negari2014; Torkamandi & Khodabakhshi Parizi Reference Torkamandi and Khodabakhshi Parizi2018). The 2021 survey concentrated on the foothills of the Jiroft Mountains, especially the plain of Jiroft, which is located in the middle of the Halil River basin, with the intention of identifying open-air artefact scatters. The plain of Jiroft is surrounded by the Jebel Barez mountain range to the east and north-east and consists of a depression filled with alluvial fans that can measure up to 300m thick in some areas. Prior to commencing the fieldwork, a geological map of the area was used to identify those alluvial fans that contained Quaternary sediments. These were divided to 1 × 1km squares and, using a systematic random sampling approach based on Burke and colleagues (Reference Burke, Smith and Zimmerman2008: 72), a team of five collected artefacts along a series of 100m transects.

Results

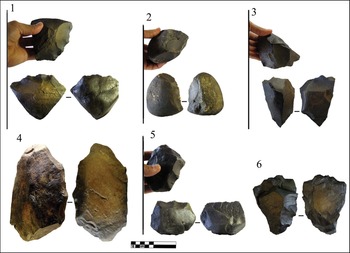

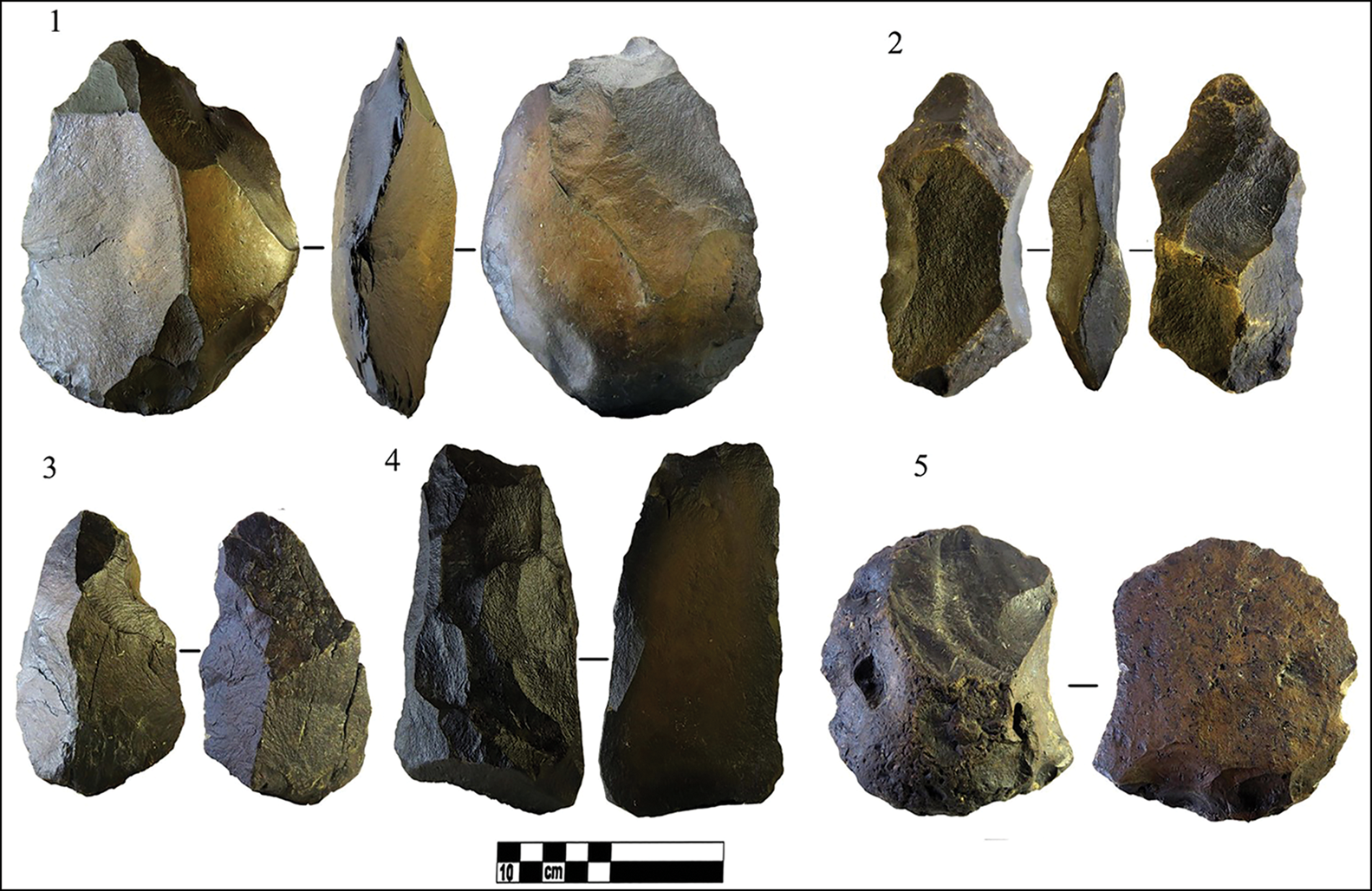

In total, 22 new Palaeolithic localities were identified and 700 lithic artefacts were collected. Due to the close proximities of some sites, however, we can identify five major surface scatters, which can also be seen as three major clusters of open-air sites (Figure 1). Evidence for all Palaeolithic periods was recovered. Diagnostic artefacts include bifaces, large scrapers, picks, cleavers and choppers (Figures 2 & 3), numerous points and centripetal Levallois cores and blanks (Figure 4), and bladelet cores, twisted blades, drills and burins (Figure 5), indicating the presence of Lower, Middle and Upper Palaeolithic/Epipalaeolithic activity. Naturally, as the issue of mixing of the artefacts in any surface scatter is inevitable, the proposed relative chronologies are based solely on the presence of diagnostic artefacts.

Figure 2. 1–3) Unfinished bifaces; 4–5) cleavers. Artefacts recovered during the 2021 survey. Scale in cm (photographs by A. Anjomrooz).

Figure 3. 1) Heavy duty scraper; 2–6) choppers. Artefacts recovered during the 2021 survey. Scale in cm (photographs by A. Anjomrooz).

Figure 4. 1, 2 & 6) Levallois points; 3–4) centripetal Levallois cores; 5) core/chopper; 7–8) Levallois flakes. Artefacts recovered during the 2021 survey. Scale in cm (photographs by A. Anjomrooz).

Figure 5. 1) Bladelet core; 2) twisted blade; 3) bladelet; 4) drill; 5–6) small burins. Artefacts recovered during the 2021 survey. Scale in cm (photographs by A. Anjomrooz).

Conclusions

Prior to the 2021 survey, evidence of Pleistocene hominin occupation was exceptionally limited in southern Iran. This is in sharp contrast with reports of numerous Palaeolithic occupations within the southern Persian Gulf, specifically in the Arabian Peninsula (Armitage et al. Reference Armitage2011; Bretzke et al. Reference Bretzke, Conard and Uerpmann2014, Reference Bretzke2022; Groucutt et al. Reference Groucutt2021). Although the significance of the lower part of the Iranian Plateau as a hominin dispersal route has been commented on by one of the authors (HVN), the need to prove such a claim via archaeological evidence was inevitable. The 2021 survey not only provides valid evidence for the presence of different groups of hominins throughout the Pleistocene, but also sheds light on the significance of the northern part of the Persian Gulf as one of the major dispersal corridors between east and west for coastal migrations out of Africa.

While there are still a number of ambiguities surrounding claims of Lower Palaeolithic sites in Iran—for example, none have resulted from excavation and none possess valid chronologies—any definitive evidence for this period can help in understanding the complex and poorly understood question of Middle Pleistocene occupation within the Iranian Plateau.

Considering the Middle Palaeolithic, the present data provide a better state of affairs. Comparison of the Middle Palaeolithic artefacts recovered during the 2021 survey with those from the northern/central Arabian Peninsula (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings2016; Bretzke et al. Reference Bretzke, Yousif and Jasim2018: fig. 3; Crassard et al. Reference Crassard2019) clearly indicates high affinities in both technology and typology. More notable are the sharp and drastic differences that exist between the Middle Palaeolithic assemblages of the Zagros Mountains in general (Heydari-Guran & Ghasidian Reference Heydari-Guran and Ghasidian2017; Nymark Jensen Reference Nymark Jensen2021), and the Marvdasht region (650km to the west) in particular (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1990: fig. 4), and those of the Arabian Peninsula and this survey. This variation may indicate that different groups of hominins (e.g. Neanderthals and early modern humans) were responsible for the production of these artefacts at different points in time during the Middle Palaeolithic.

Upper Palaeolithic/Epipalaeolithic diagnostic artefacts might be associated with modern human dispersal out of Africa around 70–50 kya, given that evidence of Upper Palaeolithic occupation dated to 40 kya onwards has been documented in numerous caves and rockshelters on the Iranian plateau (Shoaee et al. Reference Shoaee, Vahdati Nasab and Petraglia2021).

The discovery of Palaeolithic artefacts assigned to the Middle and Upper Pleistocene in the surveyed area reveals the significance of the northern part of the Persian Gulf region as a dispersal corridor, used repeatedly by different groups of hominins to expand towards eastern regions. Such expansions were by no means unidirectional and hominins could have used the same routes to return to the African continent if desired.

Acknowledgements

Survey was conducted with the permission of the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research (ICAR), no. 40010892.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency or from commercial and not-for-profit sectors.