The numerous strikes that rocked the United States during the late nineteenth century triggered the wrath of powerful opponents: employers attached to various-sized businesses, local police forces, the courts, state militias, private security agencies, and vigilantes. Late nineteenth-century US history provides many examples of these repressive forces, and historians have noted the country's comparatively cruel labor relations carried out by both public and private forces.Footnote 1 Different groups of anti-labor forces, seeking stability, control, profits, and access to of efficient and faithful laborers, employed both hard and soft forms of repression. Hard forms included arresting, beating, and sometimes killing labor activists; softer techniques involved firing and blacklisting troublemakers. During the late nineteenth century, thousands experienced the enduring sting of the blacklist, a topic that has received far too little scholarly attention.Footnote 2

This paper sheds light on the blacklisting process. Thousands of blacklisted men and women experienced multiple traumas, including long periods of financially ruinous and emotionally taxing forms of punishment. I will first make some general remarks about the process of blacklisting itself, noting the experiences of both victims and victimizers. Next, I will narrow my focus by exploring the tensions between two high-profile individuals involved in this process: blacklisting advocate J. West Goodwin (1836–1927) and his long-suffering victim, labor leader Martin Irons (1830–1900). Goodwin was a nationally recognized anti-labor union activist, promoter of business interests, vigorous social networker, and newspaperman; Irons was a charismatic and widely respected leader of the Knight of Labor who was responsible for calling and organizing strikes. Both men lived in Sedalia, Missouri, a modest-sized city that was one of the major centers of the 1886 strike against Jay Gould's massive railroad empire. Sedalia saw much railroad traffic and was home to the Missouri Pacific Railroad and the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad maintenance shops. The railroad shops were major employers in Sedalia, and members of the city's Board of Trade, including Goodwin, greatly appreciated how these worksites contributed to the city's overall prosperity. Exploring the colorful lives of these two men helps us more fully appreciate the personal ways that this form of managerial punishment expressed itself in practice.

Labor unrest was one of the chief impediments to the economic interests of those at the top of society, and most businessmen in Sedalia and elsewhere opposed all expressions of working-class disobedience. And managers at various levels kept close tabs on the workforce, especially during and immediately after strikes. Indeed, scholars have long noted the inordinate power of employers over workers. Political scientist Elizabeth Anderson has captured the near-absoluteness of their authority, noting that it is “sweeping, arbitrary, and unaccountable – not subject to notice, process, or appeal”.Footnote 3 Firing and blacklisting were obvious ways of practicing and exhibiting their control over laborers. But rather than focusing primarily on Irons's bosses – railroad supervisors who worked under Gould – this paper explores the influence of Goodwin, someone who had no direct supervisory responsibilities over Irons or any of his workmates. By highlighting Goodwin's role in reinforcing Gould's managerial interests, this paper insists that we take seriously the actions of third-party actors with respect to the question of blacklisting. Instead of examining the direct activities played by bosses in this punishment process, I investigate the pro-blacklisting actions of an urban booster who was ideologically opposed to all forms of labor militancy following the massive 1886 strike called by Irons. Goodwin saw himself as an enforcer of business power and worker subservience throughout the community and beyond. Blacklisting mutinous workers like Irons was a way to achieve what Goodwin considered community harmony, prosperity, and law and order. Goodwin's involvement in blacklisting Irons provides us with a useful and novel way of understanding the various punishing characteristics of this soft form of discipline.

The Blacklisting Process

Employers practiced blacklisting because they wanted to establish workplace control by making examples out of troublemakers in the context of labor management conflicts. Stripping men and women of their livelihoods served employers’ collective and individual interests. Essentially, promoters of this form of punishment – direct supervisors and employers representing other workplaces – sought to explicitly pit unruly workers against those who conducted their duties diligently and faithfully. Blacklisting was one of the employers’ foremost weapons meant to send unambiguous messages about what constituted inappropriate actions with the aim of disciplining others. Employers, irrespective of the type or size of workplaces they oversaw, desired employees who displayed unconditional loyalty, trustworthiness, and a sustained disinclination to participate in “disruptive labor actions”. Blacklists starkly indicated the type of workers they did not want.

Unwanted workers faced many difficulties, and we must consider the multiple stages of the blacklisting process itself. For victims, it started on the last day of labor at a particular worksite and concluded elsewhere. Relatively fortunate blacklisted men and women eventually landed on their feet, finding other sources of income shortly after experiencing the traumas of termination. But not all enjoyed these somewhat positive outcomes. Whether the victim suffered in the short or long term, removal and job-seeking were deeply unpleasant experiences that produced intense feelings of anxiety. While the victims suffered their difficulties out in the open as they scrambled to find new jobs, the people responsible for their troubles conducted their work comfortably behind closed doors, where they enjoyed renewed feelings of peace of mind after firing their targets. They relished these feelings of empowerment, enjoying the authority to fire at will. They also used their power to brand their victims with the troublemaker label. The branding process generally led to long-lasting reputational damages, hurting the former employee's future job prospects and leading to a host of lingering challenges, including hunger and homelessness, as well as feelings of depression and desperation. Writing in 1885, labor activist Eugene Debs described how the “practitioners” of this form of punishment robbed wage earners of “the means of subsistence, dogging their steps for the purpose of keeping them in idleness till gaunt hunger gnaws at their vitals, until rags bespeak their degradation and blank despair shrouds their lives”.Footnote 4 This managerial form of punishment hurt not only the discharged and blacklisted victims. News of terminations usually spread quickly and had profoundly chilling impacts on laborers generally. Writing about the experience of American workers in 1891, Eleanor Marx Aveling and Edward Aveling noted that many lived in fear of “The terrors of the black list”.Footnote 5

These terrors, combined with the weight of public opinion, prompted some state legislatures to ban the practice. By the early 1910s, twenty-three states barred employers’ from using blacklists.Footnote 6 Yet, numerous bosses unapologetically continued this practice despite laws explicitly prohibiting it. As one writer put it: “The employer's right to discharge is absolute, and the man who is deprived of a livelihood usually has no proof against the person who supplied the information.”Footnote 7 Blacklisting persisted throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and liberal-oriented state authorities and trade union lobbyists had little success stopping the practice.

What groups of workers experienced these terrors? Much of the evidence of blacklisting is shrouded in secrecy, but we have access to some evidence. Writing about blacklisting on the Burlington railroad in the late nineteenth century, historian Paul V. Black has listed twenty-eight reasons why employers put workmen on blacklists, including drunkenness, carelessness, incompetence, neglect of duty, laziness, and theft. At this company, strike activity was the ninth leading reason.Footnote 8 This paper is exclusively interested in blacklisting caused by acts of labor rebellion like strikes and union organizing. Indeed, people in positions of power singled out labor leaders, those responsible for challenging employers by calling strikes, organizing boycotts, building unions, or even voting for political candidates that employers loathed.Footnote 9 The men and women managers punished after outbursts of labor activism were typically well-respected working-class activists who had succeeded in building trust with the rank and file.

These individuals were generally committed to class struggle unionism, recognizing the type of leverage that strikes wielded, which included pressuring employers to increase wages, improve job security, and bargain fairly. Unlike more conservative unionists who sought to establish mutually respectful relationships with employers while also seeking to suppress the rebellious impulses of rank-and-filers, those committed to class struggle style unionism eagerly sought to mobilize the masses combatively, with the overarching aims of securing higher levels of power on worksites. While more moderate unionists behaved relatively diplomatically as they aimed to achieve labor-business partnerships, more radical, class struggle-style unionists were generally class-conscious and proudly defiant, recognizing the fundamentally adversarial relationships between bosses and laborers. Those who embraced the class struggle style of unionism acted in ways that challenged managers at all levels. And for these reasons, it did not take long for the most dynamic union advocates to appear on management's radar. For their part, employers, enjoying the legal right to fire whomever they wanted, took satisfaction in removing these troublemakers.

Seeking vengeance against their targets, employers embedded in various business communities received assistance from friends and strangers alike. Promoters of blacklisting generated actual lists and relied on the usefulness of word-of-mouth and newspaper messaging. From the employers’ perspective, press coverage of dissident workers was a powerful signal of who not to hire.Footnote 10 Together, those responsible for the ostracization process – employers, journalists, and members of Boards of Trade in cities of various sizes – were often geographically spread out and represented different sectors of the economy. However, they shared a common interest in avoiding the type of labor problems associated with fired individuals. Some personally knew the employers responsible for firing these men and women; others learned about the supposed firebrands from discussions at business club meetings or by reading newspapers.

The employers’ profoundly life-altering actions started a process that often continued for years after victims involuntarily left worksites. Receiving the news of firings from employers was an often-devastating experience. Such figures were immediately bombarded with feelings of concern, desperately asking themselves a series of nagging questions about how to move forward. How, they asked themselves, could they cover basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter without income sources? Income loss disruptions were not merely experienced by breadwinners. Firing victims, plagued by overwhelming feelings of unease, self-doubt, and humiliation, were left unable to assist family members who often depended on their incomes. This caused growing anxiety in families, compelling members to desperately seek new forms of employment and sources of income. Additionally, employer-provoked discharges meant more than the absence of paychecks; employers involved in the termination and blacklisting process destroyed significant parts of workers’ identities and sense of purpose, since victims were no longer able to engage in the familiar labor and social routines that brought them into contact with fellow employees. These routines, based mainly on their shared experiences with exploitation, led to bonds of solidarity and friendships. Vengeful employers robbed workers of much more than money.

Workplace removals following combative labor actions sent unmistakable messages about employers’ core demands and interests. Naturally, managers sought to create trouble-free and smoothly operating worksites, and punishing actions like firing and backlisting were intended to spread fear – and generating fear was designed to discipline the remaining workforce. Such actions, in short, were meant to shape the behaviors of those who continued laboring. Whether employers conveyed their messages explicitly is hard to know, but we can be confident that information circulated quickly following discharges, creating climates of insecurity. These feelings of uncertainty undoubtedly influenced the actions of many laborers, teaching them the necessity of demonstrating loyalty to their bosses and the importance of performing their duties productively without showing interest in unions or strikes. Blacklisted men and women were living examples of how not to behave in workplaces.

Blacklisting reached a high point in the second part of the 1880s when thousands suffered these cruelties following a series of strikes. Yet, employers were far more interested in running their businesses than addressing the traumas experienced by their victims. After discharging and blacklisting thousands of labor activists, employers hired non-unionists in their place. In 1886, employers hired 39,854 non-unionists in place of unionists. In the following year, the number of replacement laborers numbered 39,549.Footnote 11

Goodwin vs Irons

Unfortunately, very few blacklisting practitioners or victims left documents, making it difficult for researchers to recreate the lives of those from either side of these class divides. But we know that victims’ experiences were intensely upsetting, and we can patch together some relevant pieces of evidence, shedding light on both the punished and the punishers. With this goal in mind, the remaining parts of this essay explore the actions of two unusually visible figures: J. West Goodwin and Martin Irons. Goodwin was one of the nation's most prominent anti-labor union activists; he was extremely active in building employers’ associations and wrote critically about union activities locally and nationally. And Irons was, for a short period, one of the country's most powerful class-conscious labor leaders partially responsible for organizing the multiline 1886 strike against the Gould system.

Both men lived interesting lives. Born in Watertown, New York, in 1836, Goodwin, a Union veteran of the Civil War and newspaperman, made his biggest mark in Sedalia. This medium-sized Missouri city was captured by Confederate troops in October 1864.Footnote 12 The city grew modestly in the years after the war, and Goodwin became a keen booster of his adopted home in the century's final years. He enjoyed connections with powerful business and political leaders, both in and outside Sedalia, and played an important part in launching the city's Board of Trade in 1870. He opened his own publishing house in Sedalia in 1868 and edited the widely read Sedalia Bazoo. As the owner of a one-building print shop, Goodwin quickly became an influential community voice, eagerly promoting the city as a center of business prosperity and law and order. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the engines of economic growth and established close connections with prominent businessmen; his business, for example, published documents for bankers and railroad investors.Footnote 13 He earned considerable respect among his peers active in various civic affairs; in 1891, for instance, he became the president of the Missouri Press Association. According to historian Ronald T. Farrar, his Bazoo “was perhaps the most widely quoted community newspaper in the state”.Footnote 14 In 1902, Goodwin explained, “I have expressed my own convictions in the plainest and simplest words at my command”.Footnote 15 The proud Sedalian even lobbied to make his city the state capital, hoping to deprive Jefferson City of that honor. He failed in this task but remained outspoken in drawing explicit links between business interests and community stability. This meant promoting respect for the city's businessmen against any plebeian threats – dangerous, law-breaking labor actions that were more apparent elsewhere, including in larger cities like Chicago, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis, than in Sedalia. The owner-editor sought to play his own role in discouraging such actions locally.Footnote 16 As he explained in 1879: “The newspapers are upholders of law and order.”Footnote 17

The proprietor of the J. West Goodwin Publishing Company made many lasting impressions on others, including friends and foes alike. He typically wore his signature top hat in public and was generally known for his flamboyancy and hardnosed anti-unionism, which became particularly pronounced when organizers issued him ultimatums at his worksite. In January 1885, for instance, members of the International Typographical Union (ITU) sought to organize his workers, demanding that only union members work in the Bazoo office. The “gang of cut throats”, he later complained, “were endeavoring to break down the Bazoo because it would not employ Union help exclusively”.Footnote 18 It is unclear if these “cut throats” were successful; at least one source suggests that the ITU had prevailed: “The boycott was a grand success, and the result was an unconditional surrender on the part of the Bazoo proprietor.”Footnote 19 But Goodwin never admitted defeat, adamantly proclaiming that he “refused to submit”.Footnote 20 Regardless of the result of this confrontation, we can, at a minimum, conclude that Goodwin sought to protect his identity as a strong-willed business owner determined to show fellow community members his uncompromisingness in the face of challenges from below.

IIn response to this conflict, a contemplative Goodwin developed a clear anti-union philosophy. The 1885 confrontation caused him to reflect, compelling him to outline what he considered the excessiveness and absurdities of union-imposed rules. He used his platform to warn that union demands had the potential of spilling over into other areas of society: “If these men have the same right to prescribe what a man shall eat, what a man shall wear, what church he shall attend, what prices he shall receive for his goods, whom he shall marry, when and where he shall visit and in all other things do their beck and bidding.” Goodwin put his foot down, unashamedly defending his right to manage: “But the Bazoo denies that they have any such rights.”Footnote 21

Goodwin's significantly unpleasant experiences with pushy labor activists prompted him to think hard about the logic of closed-shop unionism – workplaces that employed union members exclusively. In his judgment, such workplaces did not merely threaten his personal interests; demands for exclusivity agreements, he reasoned, were wholly incompatible with basic American freedoms. As we will see, Goodwin believed that he had the ultimate authority to manage his workplace as he alone saw fit. He stuck to this core belief throughout his life.

Born in Dundee, Scotland, Irons had a fundamentally different outlook on life, labor, and industrial society generally. Arriving in New York City at the age of fourteen, shortly before the Civil War, Irons soon found employment in a machine shop before departing to other parts of the nation, including New Orleans. He was appalled by the working conditions he encountered in both regions, which caused him to draw revolutionary conclusions about what he considered the necessity of emancipating “my fellow-workingmen from their wage-bondage”.Footnote 22 During the 1870s, Irons faced numerous difficulties navigating the job market and thus experienced periodic bouts of unemployment. Economic pressures ensured that he was often on the go, moving from different locations in the South and Midwest, settling in places like Lexington, Kentucky, Kanas City, Kansas, and Joplin, Missouri. In this decade, he became active in the Grange, an organization that promoted the rights of farmers and small businesspeople. But he did not believe that businessmen, irrespective of the size of their operations, would serve in a vanguard role in transforming industrial society. He found a more plausible vehicle for liberation when he moved to Sedalia in the early 1880s. Shortly before Goodwin faced his own labor challenges, Irons became an active member of the Knights of Labor (KOL), a mostly inclusive and largely decentralized labor union that emerged in 1869.Footnote 23

The KOL opened membership to most workers and even invited small businessmen to join. However, it prohibited lawyers, corporate leaders, and Chinese workers from holding membership.Footnote 24 Most of all, members believed that wage earners needed to assert more control over the labor process, and participants repeatedly complained about the emergence and spread of industrial monopolies. These powerful economic entities threatened what KOL spokespersons called the “nobility of toil”.Footnote 25 The union, which essentially functioned as a labor and political organization, reached a peak membership of over 700,000 members nationally in 1886.Footnote 26 Sedalia hosted five KOL assembles at this time, numbering about 1,000, mostly railroad workers. Around this time, Irons, holding a deeply held hatred of inequality and exploitation, became a trusted leader who demonstrated a willingness to fight on behalf of the membership.Footnote 27

KOL members staged strikes to address injustices, and sometimes the union achieved critical victories, including in March 1885, when members across multiple states halted most of Jay Gould's freight trains. This relatively peaceful affair led to wage increases and improved job security for members. Labor movement representatives, gleeful about the triumph, commented on what appeared to be a pro-union atmosphere in Sedalia following the successful work stoppage: “Work in the railroad shops is fair and the men are all well treated since the great strike.” According to this May 1885 report, that strike may have motivated laborers in other sectors of the city's economy to organize: “The painters, carpenters, tailors and bricklayers have all organized within the past month, and trade unionism is fairly booming in this city.”Footnote 28 Clearly, railroad victors inspired others, persuading the city's diverse set of laborers to organize with one another and seek ways to extract benefits and win respect from their bosses.

Emboldened by the strike victory against the era's quintessential robber baron the previous year, combined with the growing popularity and legitimacy of labor unionism generally, KOL members staged a second work stoppage in March 1886 because employers reneged on their contractual agreements and, in KOL members’ views, unfairly fired C.A. Hall, an employee from the Texas and Pacific Railway shop in Marshall, Texas. As the KOL District Assembly 101 leader, Irons rallied members to Hall's cause and, more broadly, to the defense of union rights. Irons played an instrumental role in building and sustaining the strike during membership meetings and on picket lines. As historian Theresa Case has put it, he approached the confrontation with “determined leadership”.Footnote 29 He spoke from the heart and was, by most accounts, an inspirational orator, effective motivator, and principled leader. According to historian Ruth Allen, fellow KOL members were sometimes “moved to tears by an Irons’ speech” while others were entranced by “his emotional power as a speaker”.Footnote 30

Emotion partially drove the 1886 railroad strike. The extremely disruptive and often violent affair involved roughly 200,000 participants from five states. Members from railroad towns in Missouri to Texas dropped their tools and left their stations, organized planning meetings, mobilized to prevent strikebreakers from crossing picket lines, and defaced company property. Some damaged train engines, vandalized tracks, and confronted and beat strikebreakers and supervisors while demanding that Gould and his managers bargain with the KOL and treat members with fairness and respect. The type of disorderly actions that urban boosters like Goodwin had long wanted to avoid had exploded in his beloved Sedalia.

Gould stood his ground in the face of the unrest and, with help from armed forces, chose to combat the strikers directly with the aim of undermining the union and creating workplaces where managers could more freely hire and fire employees at will. He received help from both public and private sector anti-unionists, including vigilantes active in armed, hyper-secretive Law and Order Leagues, businessmen militias that first emerged in Sedalia before spreading to other Midwestern communities. The Leagues were led by well-connected businessmen representing a diversity of worksites who systematically intimidated strikers and defended scabs at or near railroad tracks. Though membership numbers are unavailable, the Law and Order League's leadership consisted of lawyers, merchants, manufacturers, and politicians – the “best” citizens in Midwestern towns and cities. For example, E.W. Stevens, Sedalia's future mayor and a successful mule trader, was one of the organization's leaders.Footnote 31 Socioeconomically, these men fit the description of what writer Patrick Wyman called the “American gentry”, those who sat “at the pinnacle of America's local hierarchies”.Footnote 32 Though economically less influential than the era's extraordinarily powerful robber barons like Gould and Andrew Carnegie, they were nevertheless relatively wealthy, politically important, and supremely self-righteous who demanded that their core values – respect for private property, support for unfettered economic growth, and community stability – must predominate. As Goodwin put it in April: “Law and order is indispensable. It must and shall prevail.”Footnote 33 In the face of these confrontations, Jay Gould said nothing about businessmen-orchestrated violence but shamelessly insulted strikers, whom he called a “mob” (Figure 1). Goodwin gave space to Gould's words in his paper: “At present it is only a question of the dictation of a mob against law and order.”Footnote 34

Figure 1. Cartoon, “Jay Gould's Private Bowling Alley”. Like other late nineteenth-century “captains of industry”, Gould despised labor unions and instructed his management team to fire and blacklist strikers. A slate shows Gould's controlling holdings in various corporations, including Western Union, Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the Wabash Railroad. Illustration by Frederick Burr Opper from Puck, 29 March 1882, cover. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-28461, Washington, D.C., United States.

Goodwin fought the strike in two basic ways. First, as a Law and Order League participant, he was part of an organization consisting of armed men who escorted scabs, tormented strikers, and showcased their determination to impose order on the larger community. In a series of menacing actions, these men, equipped with firearms, protected trains and accompanied strikebreakers to worksites. One report pointed out that “bands of armed men” mobilized “night and day”.Footnote 35 In the process, it is likely that participants established greater solidarity with one another. These direct actions inspired elites in other communities plagued with similar outbursts of labor militancy to form their own Law and Order Leagues. During the multistate strike, members of local gentries in Belleville, Illinois, Parsons, Kansas, and St. Louis, Missouri, emulating the Sedalia example, formed their own belligerent Law and Order Leagues.Footnote 36

Second, Goodwin's newspaper served as a mouthpiece for those who opposed the belligerency of the strikers, reporting shortly after the strike's collapse that the paper had gained popularity because of “the position he [Goodwin] has taken in regard to the strike”.Footnote 37 In Goodwin's interpretation, the paper, by opposing the strike, reflected the larger community's views. We can assume that this was a self-serving comment that mirrored the views of his class members rather than the opinion of all of Sedalia's residents, irrespective of their socioeconomic position. After all, in most communities, class consciousness had spread, union density had grown in the aftermath of the 1885 strike, and many railroaders had decided to participate in the 1886 action. For these reasons, it is improbable that the city's working-class population – most of Sedalia – had suddenly become sympathetic to the interests of their local bosses or Jay Gould, one of the nation's most despised men. Whatever the case, Goodwin ran multiple stories in his paper celebrating what he described as the fearless counteractivities of citizen anti-strike activists while denouncing the actions of the strikers and their leader.

The repressive actions carried out by the Law and Order League are noteworthy and raise questions about the actions of private armed citizens. Above all, why did these men form a vigilante organization when Sedalia had its own police force? We can speculate. Significantly, there is no evidence that spokespersons for the city's police force or state troops objected to Sedalia's Law and Order League's actions. In fact, Goodwin wholeheartedly praised the diversity of strikebreaking actors. In addition to spotlighting the decisive actions of his Law and Order League, he celebrated the actions of the deputy sheriffs who, in his words, provided “valiant service”.Footnote 38 It is probable that these deputy sheriffs were also Law and Order League members. Whatever the case, the lesson was clear enough: private and public sector forces complemented, rather than competed, with one another. Public and private sector forces systematically surveilled and targeted the same groups with the central aims of protecting property, restoring order, and punishing noncompliant laborers. This point is consistent with the astute observations made by David Churchill, Dolores Janiewski, and Pieter Leloup, who have insisted that we reject “a narrow focus on ‘the police’” and instead embrace “broader conceptions of ‘policing’ and ‘security’”.Footnote 39 Joint strikebreaking actions conducted during the 1886 strike, all of which served the ruling class's interests, illustrate the correctness of this line of reasoning.

But the question remains: why did Goodwin and fellow Sedalian elites – as well as businessmen in other cities – feel compelled to organize their own possies given the “valiant” services of public sector authorities? One possible reason is that they enjoyed the thrill of directly combating members of the so-called dangerous classes. A more plausible explanation is their collective realization that direct action was the most efficient way to intimidate and expel protesters, protect strikebreakers, further cement ruling-class comradeship, and ultimately end the conflict. Whatever the case, the swift emergence of the Law and Order Leagues highlights an important and often overlooked example of ruling-class self-activity.

Indeed, the repressive forces deployed by these men ultimately led to Gould's victory. Descriptions of exactly how these “bands of armed men” conducted themselves are unavailable, which must not surprise us given the organization's commitment to secrecy. Few sources describe their gutsy actions, including their conversations with one another in meetings, the types of weapons they selected, or the precise nature of their relationships with public sector authorities like judges and police officials. But we can be sure their involvement was significant in concluding the strike on terms favorable to Gould and his management team. Years later, in a somewhat self-serving way, Goodwin reminded readers of what he deemed the Law and Order League's essentialness, writing in 1889 that it “was the most important factor in” ending the strike.Footnote 40

Labor management relations remained extraordinarily tense following the confrontation in early May. Defeated wage earners naturally felt demoralized while also recognizing the necessity to move on; they had families to support, bills to pay, and painful memories to forget. Despite their collective feelings of bitterness, they wanted their old jobs back, recognizing that the experiences of exploitation under dictatorial bosses were far better than suffering the bite of unemployment with no income. But they faced serious stumbling blocks from grudge-holding and conflict-adverse managers, those who desired a future of relatively harmonious labor relations. For obvious reasons, hiring managers sought long-term industrial stability and thus remained unwilling to reemploy the active participants of what Gould had called “a mob”.

As the strike came to an end, Goodwin used his platform to distinguish between those who had a future with the company and those who did not. Loyal men, he wrote, “will be taken back, but they must be reemployed as free men, not as blind tools of any men or set of men”. In other words, Gould and his management team, led by the general manager H. M. Hoxie, with help from Goodwin, sought a union-free future in Sedalia's shops. “Free men”, as opposed to demanding union members, were, from the vantage point of managers at all levels, trustworthy and unwilling to withdraw their labor power, hold membership in unions, or show any expressions of disloyalty. “Free men”, in other words, had individual agency and thus emphatically rejected disruptive unions, promised to work during strikes, and demonstrated an eagerness to assist in developing and nurturing a climate of industrial stability and community harmony. “Free men” instinctively embraced independence and showed common sense. Of course, Goodwin recognized that not all accepted the idea of “free labor,” and he echoed managers by insisting that KOL members avoid Sedalia's railroad shops. After a delegation of Sedalia's Law and Order League members participated in a fruitful meeting with Hoxie in St. Louis in April, Goodwin informed local jobseekers of their future prospects: “Those among the strikers of the Martin Irons type; those who have been agitators and leaders of mobs and guilty of overt acts of violence and destruction, will not be taken back on any terms.”Footnote 41

Goodwin was at least partially correct about the punishments that awaited labor activists. But perhaps he was overly optimistic about the overall numbers of “employable” “free men” residing in railroad communities like Sedalia. The number of those who returned to work was relatively small. According to The Railway Age, after the 1886 strike, one of Gould's branches, the Missouri and Pacific system, rehired fewer than 200, representing a small fraction of the 4,600 who had worked for the system before the strike.Footnote 42 Further south, thousands of other veteran strikers faced similar rejections. In his study of this labor conflict in Arkansas, historian Matthew Hild reported that about ninety-five percent of Little Rock-based railroad strikers had not returned to work following the strike's collapse, though many had wanted to.Footnote 43 Based on these numbers, we can assume that sizable numbers of jobhunters were, in fact, of the “Martin Irons type” – class-conscious men who valued combativity and solidarity over submissiveness and individualism.

Thousands of “Martin Irons” types faced uncertain futures, forced to fend for themselves in an increasingly hostile job market. Of course, many likely slipped through the cracks, ultimately securing jobs in new communities. But the most visible union activists were probably deeply unfortunate, constantly compelled to move from place to place. Meanwhile, these post-strike hardships, apparent to victims and viewers alike, offered employers an opportunity to educate the “free men”, those who remained on worksites, about how not to behave in workplace settings. Managers sent a clear message to laborers in general: strike activity led to long-term joblessness and perhaps permanent stigmatization.Footnote 44

Predictably, no one seemed to have suffered more than Irons himself in this repressive atmosphere of managerial revenge. Loss of income was just one of his problems, and his multiple adversaries appeared to have relished the various punishments that awaited him. For example, in August 1886, The Railway Age correctly predicted that this activist would spend his future in distress, incapable of venturing “with safety in some places”.Footnote 45 And no one was more determined to promote this punishment than Goodwin, whose hatred for the Scottish-born labor leader lingered for years. Goodwin kept his name in the news for more than a decade after the strike, labeling him “an ignorant Englishman”.Footnote 46

Many former strikers apparently shared Goodwin's anger and intolerance, and numerous people from across class lines, as historian Therese Case has shown, “blamed Martin Irons” for the strike's disastrous outcome.Footnote 47 Indeed, frequently made in newspapers and evidently repeated by ordinary citizens, disdainful name-calling had grave consequences. Goodwin and his allies wanted to isolate and demoralize Irons even before the strike ended. As the strike entered its closing stages in mid-April, Goodwin featured stories about what appeared to be Irons's deteriorating health. Irons “looked ten years older than he did before the strike”, remarked an unnamed commentator in the Bazoo a month after the Law and Order League's emergence.Footnote 48 This was probably accurate, given the circumstances. Indeed, Irons's feelings of worry probably increased as armed Law and Order League members, perhaps including Goodwin, aggressively confronted strikers while helping armies of strikebreakers to cross picket lines. By this time, he and his fellow strikers had been thoroughly outgunned and effectively overwhelmed by well-funded and highly organized adversaries.

Irons departed Sedalia in late May, the beginning of his long decline. His experiences as a blacklisted man were, by all reports, overwhelming. This punishment was long-lasting, enforced by employers, and supported by journalists and law enforcement officials. For his part, Goodwin frequently reminded readers about the results of what he regarded as Irons's ill-informed choices. After the strike, the distraught father of five struggled to secure steady employment as a boilermaker or machinist but was repeatedly turned down by hiring managers, forced to move from community to community, where he endured years of joblessness and underemployment. In response to repeated rejections and humiliating encounters, Irons sometimes wore disguises and often changed his name, hoping to evade detection and obtain work, though observers usually outed him. Indeed, disguises offered only temporary protections – if any protection at all. Clearly, Irons was consistently on edge, forced to develop creative strategies to sustain himself financially.

Irons's blacklist-generated scars were undoubtedly visible after the strike's collapse. Newspaper reporters continued to view him as a subject of considerable interest, routinely reminding readers about his numerous post-strike defeats. A Kansas source reported in July 1886 that he was “broken in mind, pocket and spirit” while living in Rosedale, Kansas.Footnote 49 Years later, writers made similar observations, revealing that employers remained unwilling to hire him, prolonging Irons's anxiety and desperation. An unknown number of employers made their feelings clear when Irons approached them with job applications. “Whenever Martin Irons applied for work”, another newspaper reported in 1888, “he was driven away with imprecations”.Footnote 50 Rather than simply reject his applications, mean-spirited employers took additional steps. They treated him with total disrespect, demanding that he permanently stay away from their worksites and communities. These harrowing experiences forced Irons to travel great distances, many miles away from Sedalia. Desperate for an income, Irons spent some time in St. Louis selling peanuts before moving to rural parts of Missouri and Fort Worth, Texas.Footnote 51

The absence of a steady income was not Irons's only source of concern. As a drifter constantly job-seeking, he was vulnerable to various forms of abuse, insults, invasive monitoring, and annoying inconveniences. For example, railroad managers instructed their agents to refuse to sell him tickets, forcing Irons to travel on mostly poorly maintained rural roads on horse-drawn buggies.Footnote 52 Moreover, he enjoyed very little privacy or peace of mind. Pinkerton security agents scrutinized his movements, and policemen periodically arrested him for the “crime” of vagrancy. As an incomeless person, he was forced to spend extensive amounts of time on the streets, where he was susceptible to the harassment of both public and private sector “law and order” enforcers. In addition to experiencing the precariousness of semi-homelessness, Irons dealt with the aggravations of short incarceration stays, essentially experiencing what historian Bryan D. Palmer has called “the criminalization of the out-of-work”.Footnote 53 Thoroughly depressed by these traumatizing experiences, Irons sought to drown his sorrows in alcohol, which probably contributed to his declining health. In 1897, another Kansas newspaper reported rather bluntly that Irons “has had a hard struggle with the world since the great Missouri Pacific strike”.Footnote 54

But prolonged periods of living with the difficulties of financial insecurity, police harassment, and health problems did not convince him to retreat from his political commitments, which included his desire to build working-class organizations, fight oligarchs, and point out capitalism's inherent maliciousness. According to one source, he remained “more extreme than ever in his views”.Footnote 55 He continued to show an inclination to participate in class struggles in his advanced age; in regions of Texas, for instance, he organized tenant farmers. Such activism showed that he was not simply a victim of the abuses unleashed by members of the capitalist class. He remained committed to advancing the class interests of ordinary people even though, in the words of one writer, “his health and spirits failed him”.Footnote 56 We can assume that Irons embraced anti-capitalist views because of his experiences as a labor leader and semi-homeless person, as well as his decades-old observations of the ways the economic system adversely impacted proletarians in general; the different hats he wore had provided him with painful lessons about capitalism's innate and multifaceted cruelties. Irons's visual appearances offered plenty of evidence of how his encounters with a series of microaggressions and major setbacks had impacted him. At the end of his life, he settled near Waco, Texas, where, according to Eugene Debs, he “bore the traces of poverty and broken health”.Footnote 57 Practically penniless, Irons died in 1900. Another socialist blamed Irons's death on his old nemesis: “Jay Gould found he could not buy him, so he hounded him to death.”Footnote 58

Goodwin's Wrath

Goodwin played a critical role in helping Gould in the hounding process. Of course, he was not exclusively responsible for Irons's post-strike difficulties, but he served an important role. Indeed, the newspaperman served Gould's interest by keeping Irons's name in the news years after the strike, telling and retelling Bazoo readers what he considered the labor leader's moral weaknesses and imprudence. Goodwin's contempt for Irons was rooted in the newspaperman's annoying personal experiences, philosophical opposition to closed-shop unionism, and deep loathing of labor unrest and expressions of working-class insubordination generally. Perhaps his writings were also motivated by something else: the $1,000 Gould reportedly paid him annually for several years following the strike to keep Irons's name in the news. Gould and Goodwin had apparently made a deal whereby the powerful executive promised to compensate the newspaperman for reminding readers of the labor leader's supposed wickedness and error-driven ways.Footnote 59 Clearly, Gould and Goodwin wanted this blacklist to withstand the last years of Irons's life.

Goodwin did his part in at least two ways: he wrote blistering attacks on Irons and allowed others to speak about the labor leader's supposed poor choices, immorality, and general recklessness. We can identify the significance of both approaches, including the second one. After all, the words of a Law and Order League member like Goodwin likely had less of an impact on many readers than the statements of ordinary Sedalians, including former KOL members. By elevating these voices, Goodwin added credibility to the broader anti-union movement since it showed that opposition to labor leaders and their endorsement of militant activities was not restricted to business owners or managers. Instead, these people articulated their grievances from different class positions, protesting that they had been tragically misled by irresponsible men like Irons.

Consider some examples. According to a Bazoo article published in May 1886, one unidentified Sedalia resident denounced Irons as “a liar and scoundrel”.Footnote 60 Others wrote letters to Goodwin's paper, apologizing for following Irons's instructions and participating in the disastrous strike. “I am a striker”, one unnamed machinist regretted, “but here recently I have been asking myself, ‘why did we strike!’ and the answer comes back, ‘because Martin Irons ordered it’”. The consequences of the strike – led by what this commentator called “a heartless wretch at best” – led to innumerable hardships for the thousands of participants and their families. This person – if this author was an actual KOL member and not Goodwin or one of his Law and Order League allies – declared that Irons deserved the ultimate punishment: “The graveyard is the place for such men as Martin Irons. Six feet of rope and then drop him. Public sympathy demands it.” Another sensible alternative, according to this writer, involved getting him “fired from our country”.Footnote 61 From the standpoint of this remorseful yet outraged rank-and-filer, death or banishment constituted the best solution.

At least some KOL members remained frustrated by the strike's outcome, and many probably conveyed sincere disappointment with Irons. Yet, we can be sure that many continued to support Irons and expressed frustration with those responsible for the consequences of the industrial action, including Gould and Goodwin's Law and Order League. Obviously, Goodwin had no interest in providing a platform to anyone who raised their voices against expressions of managerial unfairness, outbreaks of repression, or the extreme inequality that characterized Gilded Age America. Clearly, Goodwin had a keen interest in keeping the public narrowly focused on Irons and reminding Sedalia's workers to show unqualified loyalty to their employers by rejecting strikes and subordinately following the orders of their supervisors. That, after all, is how “free men” behaved.

Goodwin sought to demonstrate that observers outside of Sedalia also felt justifiably outraged about Irons. One supposed “reputable citizen of Lexington, Mo” noted soon after the strike that Irons “is a man of no standing, personally or otherwise, in the community”. His badly tarnished reputation predated the confrontation, according to this “reputable citizen”: “Irons was considered a low man, contemptible, wife-beater, a drunken loafer.”Footnote 62 The “reputable citizen”, readers discovered, wanted citizens to recognize that the 1886 strike was ignited by an irresponsible man, not by structural factors or by dictatorial bosses. Moreover, Goodwin wanted readers to believe that Irons's shortcomings were not limited to his role as a labor leader, and Goodwin gave space to this “reputable citizen” to attack Irons's general character.

Goodwin wrote punchy editorials, echoing the rage supposedly conveyed by former strikers and “reputable citizens”. He did so with the goal of ensuring that Irons remained incapable of securing a platform to promote his anti-capitalist opinions. “Mr. Irons had better keep still”, Goodwin wrote in 1889, “as no one of respectability will believe him”.Footnote 63 In Goodwin's opinion, Irons was eternally smeared with the stigma of labor rebellion, which meant that he lacked credibility in any decent society. Yet, Goodwin's words here appear that he may have harbored haunting concerns about Irons's potential influence, uneasily recalling his capacity to rally combative demonstrators in 1886. Goodwin's writings hint at the possibility that he and his colleagues remained somewhat tense, perhaps fearful of a possible repeat of disruptive industrial actions like strikes. Perhaps Goodwin dreaded the possibility of the emergence of another disgruntled labor activist. Such a person, he feared, had the potential to challenge railroad managers and thus create economic disruptions, chaos, and threats to “law and order”. By highlighting Irons's misdeeds, Goodwin sought to send a clear message to others: labor rebellion led to livelihood-destroying outcomes. Workers could avoid this punishment by demonstrating total devotion to their jobs. In Goodwin's view, self-respecting workers rejected labor unions and became “free men”. According to this logic, free men eagerly and efficiently toiled without holding labor union memberships.

Half a decade after the strike's collapse, Irons painfully acknowledged Goodwin's role in contributing to his misery when a Sedalia resident described a short meeting he had with the legendary drifter. Irons wanted to know about his former community: “He wanted to know if the Bazoo was still in the land of the living and published for the people now on earth. I told him ‘by a large majority’.” Irons responded with a “grunt”.Footnote 64 This response illustrates Irons's pent-up aggravation and demonstrates that Goodwin had obviously achieved one of his objectives. While Goodwin was obviously not solely responsible for Irons's years of unhappiness, the labor leader clearly acknowledged that the newspaperman played a part in his punishment.

Achieving the goals of punishing Irons in particular, intimidating wage earners generally, and advancing the interests of managers and “free men” required considerable efforts on Goodwin's part. The enthusiastic urban booster was left feeling vulnerable and perhaps a bit embarrassed during the 1886 strike; this enormously disruptive job action was especially troubling to him because a fellow Sedalian had led it. That strike and the growth of labor unionism in the city in the mid-1880s threatened the interests that he and his fellow Board of Trade members deeply cherished: business prosperity, managerial control, and the presence of a community that obeyed the law. Goodwin was, first and foremost, a champion of business interests, and this newspaperman, booster, and law and order advocate took extraordinary steps in the areas of labor and public relations: helping to build Sedalia's Law and Order League, denouncing strikes in the pages of the Bazoo, tarring Irons's name during the labor leader's final years of life, and inviting “free men” to labor in the city's workplaces. By routinely drawing attention to what he considered Irons's offenses in the years after the strike, Goodwin illustrated his critical role in the blacklisting process.

Goodwin and the Ongoing Fight Against Labor

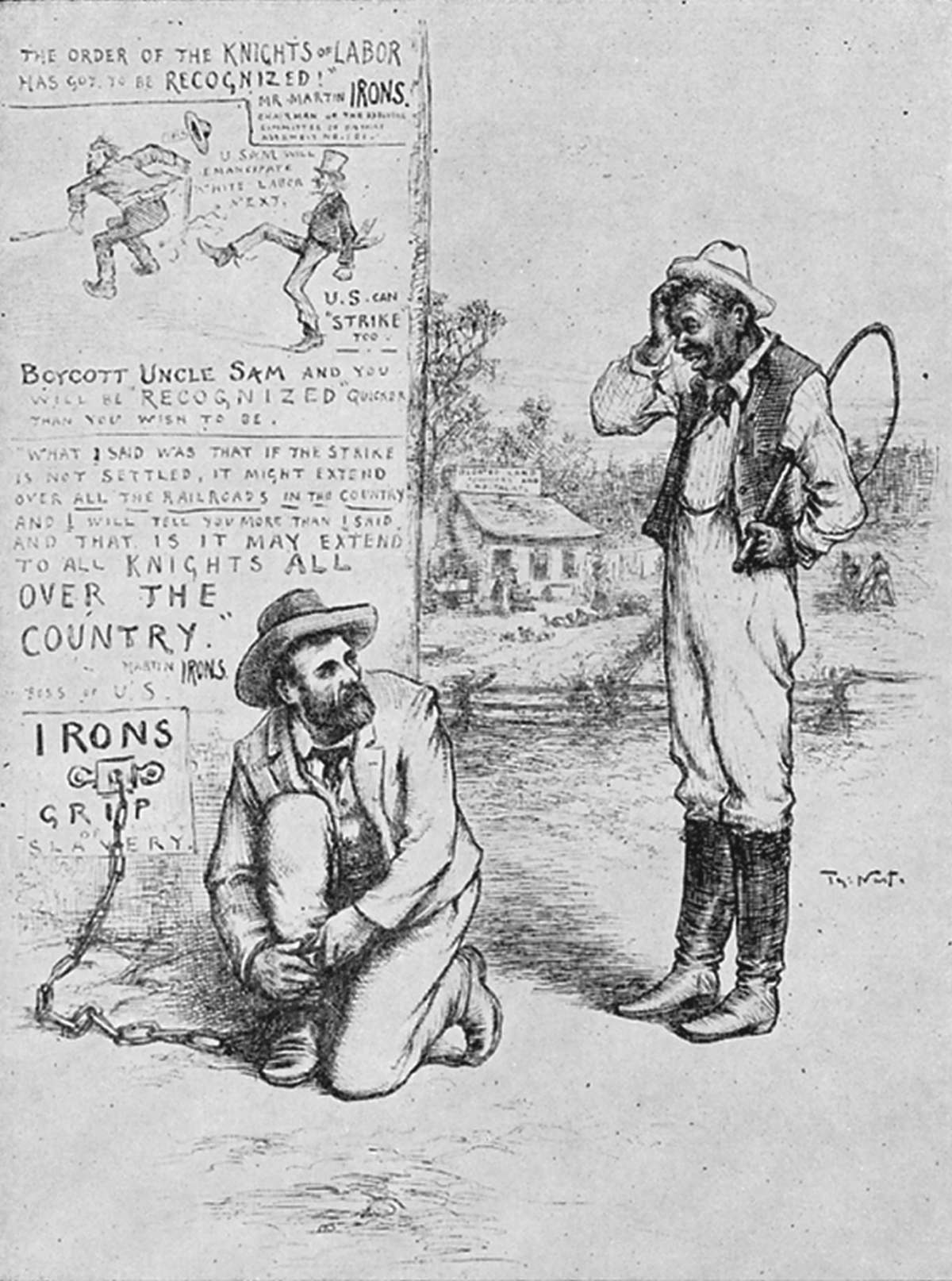

Irons's death did not cause Goodwin to stop advocating for business interests or cease his efforts against organized labor in the name of law and order. And the notorious blacklisting of Irons hardly stopped the labor movement (Figure 2). In the early twentieth century, when growing numbers of skilled and unskilled workers across different industries staged strikes and protests for union recognition, Goodwin led several recruitment trips to cities around the country to convince businessmen to join the anti-labor union open-shop movement. Most notably, he was one of the chief organizers of the Citizens’ Alliances, a collection of extremely secretive organizations that brought together employers, lawyers, judges, journalists, and clergymen in cities throughout the nation. By 1910, there were over 500 chapters of these organizations. In 1903, Goodwin boasted that he was “the Christopher Columbus” of this second movement and was “probably more responsible for the formation of the first Citizens’ Alliance than any other man on this soil”.Footnote 65 In these years, Goodwin inspired employers and policed labor well beyond Sedalia's borders. Like those from the mid-1880s, Citizens’ Alliance members during the misnamed “Progressive Era” discussed managerial techniques, condemned closed-shop unionism, shared blacklists of union members, and pitted labor activists against “free men” – scabs willing to cross picket lines.Footnote 66

Figure 2. Cartoonist Thomas Nast echoed railroad officials in casting the Southwest strikers as foes of the free labor system, caught in the ideological “grip” of Missouri union leader Martin Irons and the voluntary “slavery” of unionism. In the cartoon, the choices exercised by white labor baffle a freedman. Nast's depiction ignored the widespread participation in the strike by both black and white railroaders and the popular support on Gould's roads for the union strike order. Harper's Weekly, 17 April 1886.

In writing about his history of anti-labor union organizing during the new century, Goodwin touted his community's involvement in unionbusting during the 1886 railroad strike. The mobilization of KOL strikers coincided with the development of, as he put it in 1903, “an uprising on the other side”: the growth of the Law and Order League movement. In his immodest telling, Sedalia's “people flocked to the organization in great numbers”. Together they helped to put down “lawlessness” while “restoring peace to the communities and compelling the due observance of property rights”.Footnote 67 Goodwin's contributions to direct strikebreaking, combined with his promotion of anti-labor propaganda more than a decade before employers’ active in organizations like the National Association of Manufacturers launched a vicious open-shop movement, help us understand why large numbers of union haters throughout the nation requested his assistance in building Citizens’ Alliances and battling labor activists in their communities.

Conclusion

Why does the conflict between Goodwin and Irons matter? Most significantly, Goodwin's actions help us understand how a powerful individual on the sidelines assisted in making Irons's life precarious while helping to undermine the labor movement generally. We can draw meaningful lessons from their experiences during and after the 1886 railroad strike. The strike and its aftermath had pitted one of the country's most visible strike leaders against one of the nation's most vocal anti-labor spokespersons. That both men lived in a relatively small city is perhaps coincidental. Observers of the so-called labor problem had their eyes set on events in this city during and immediately after the confrontation. As an influential opinion maker with close ties to employers and journalists throughout the Midwest, Goodwin was in a privileged position to shape the narrative of the strike and its aftermath while inspiring anti-union figures from other cities to form their own unionbusting organizations. Goodwin's self-serving narratives, repeatedly articulated in the pages of the Bazoo, were, essentially, simple morality tales: the city's heroic citizens, seeking to protect the interests of “free men” and resume commerce, had helped to put down a lawless strike led by an irredeemable man. As a journalist with a significant reach, Goodwin played a key, though far from exclusive, part in punishing Irons.

That significant numbers followed Goodwin's actions demonstrates that employer organizing, employee surveillance, blacklisting, and the trash-talking of rebellious wage earners were not limited to Sedalia. The many men who joined Goodwin in Law and Order Leagues in the 1880s and Citizens’ Alliances at the turn of the century illustrate the growing importance that members of the nation's occupationally diverse ruling classes placed on building and sustaining counter-organizations, monitoring workers, bad-mouthing disobedient former employees, and employing punishing techniques like firing and blacklisting. Powerful businesses continue these vile practices today. We can, for example, draw comparisons between Amazon's disrespectful treatment of labor leader Chris Smalls with how members of the ruling class and their agents treated Irons. While Goodwin condemned Irons as “ignorant”, Amazon's arrogant managers and lawyers have referred to Smalls – the proud, grassroots organizer fired for leading a walkout in early 2020 at one of the retail giant's massive warehouses in New York City – as “not smart or articulate”. Two years after staging this dramatic action and months after helping to successfully organize that same warehouse, Smalls – whose determination to improve the conditions of his workmates mirrors the demands articulated more than a century ago by Irons – cannot secure work at Amazon.Footnote 68 The unremorseful objective remains consistent: smear leaders with the aim of punishing them while discouraging others from following their examples.

Plenty of others uninvolved in employers’ associations, both past and present, have played junior roles in this form of managerial punishment. Employers with disproportionate power over workers have never needed to look far to discover the perks of blacklisting troublesome workers. After all, joblessness often led to countless other challenges, including financial insecurity, hostile meetings with law enforcement officials, poor health outcomes, and probably early deaths. Blacklisting, Irons's life reveals most clearly, was the punishment that kept punishing – and an illustration of how to terrify workers into submission.

This form of punishment undoubtedly shaped broader workplace and community environments, where countless other laborers experienced what Eleanor Marx Aveling and Edward Aveling identified as the “terrors of the black list”. Indeed, the presence of blacklists communicated broader messages to workers considering challenging their employers. That people like Irons and many others faced years of financial precarity, emotional abuses, and occasional physical attacks – revealed in numerous news sources – surely convinced sizable numbers to think twice before joining unions and participating in labor actions; how many chose to reject or abandon unions, labor diligently, and avoid conflicts with their bosses is impossible to measure with exactness, but we can be confident that many picked the path of least resistance. Blacklisting helped impose greater amounts of market discipline on the workforce and, in the process, revealed the enormous power wielded by employers and their allies. Blacklisting did not end class conflicts, but this method of managerial punishment injured the most impassioned labor activists and, in the process, sent worrying messages to others considering challenging their bosses.