1 Approaches to Digital Literary Mapping

[I]mprecision should be shown as precisely as possible.

[R]esistance to cartography is itself possessed of a truth function.

This Element reconsiders what the focus of digital literary mapping should be for a subject like English Literature, what digital tools should be employed and to what interpretative ends. How can we harness the digital to find new ways of understanding spatial meaning in the Humanities? This short study offers a new way forward that focusses on mapping literature not just in absolute ways (onto pre-existing maps of the world) but also by relative means, using topology. A chronotopic approach understands the inter-fused nature of time and space (the chronotope) to be a vital constituent of literary works that requires alternative mapping methods. We argue that the creation of ‘literary topology’ as a new means of visualising and interpreting fictional and poetic time-space is not merely a preferable option to standard forms of mapping, but is inherently more suited to the needs of the Humanities.

In Section 1, we provide an overview of core concerns and questions that relate specifically to the digital mapping of literary place and space in order to contextualise and position our chronotopic approach. The Digital and Spatial Humanities is a relatively new field that is still in the process of self-definition. In a special issue of DH Quarterly focussed on Literary Studies, Pressman and Swanstrom state that

[t]he Digital Humanities should not be understood as a new insurgent group retaliating against an older order. Instead, the DH identifies an emergent perspective for seeing how traditional literary scholarship provides the means for asking and pursuing interpretative questions, both about digital culture but also about other, older, and non-digital objects of study.

We fully agree with such a statement. At the heart of DH lies a productive tension between scientific tools and the uses to which those tools are put, as well as between the interpretative methods and aims of traditional Humanities subjects and the application of such tools (or not) to these aims.

Broadly speaking, for the Sciences, knowledge (and thus the methods and tools by which knowledge is sought) is understood to be absolute, objective, evidence-based, and empirical. In contrast, for the Humanities, knowledge and understanding are of a radically different order: experiential, open to interpretation, ambiguous, multiple, changing, and open-ended. The medium in which such knowledge is held, and through which it is communicated, is that of language, in relation to which absolute understanding is often not an achievable goal (particularly in the most linguistically complex forms, for example, poetry). We argue therefore that subjectivity is necessarily built into any Humanities approach, even a computational one, and forms part of the subject under investigation. Equally, the fact that many digital projects are also essentially textual means that Humanities-based skills can come to the fore, if permitted.

While DH tools must remain necessarily ‘scientific’ to some degree (based upon mathematical and geometric models and algorithms), the uses to which they are put and the nature of the visualisations they produce do not have to be. Here Johanna Drucker’s arguments are illuminating. Drucker makes a strong case for the need to reclaim visualisation tools for the Humanities:

The majority of information graphics … are shaped by the disciplines from which they have sprung: statistic, empirical sciences, and business. Can these graphic languages serve humanistic fields where interpretation, ambiguity, inference, and qualitative judgment take priority over quantitative statements and presentations of ‘facts’?

Focussed on the user interface, she sets out to ‘consider how to serve a humanistic agenda by thinking about ways to visualize interpretation’ (vii). Thus, she makes a core distinction between two kinds of visualisation:

A basic distinction can be made between visualizations that are representations of information already known and those that are knowledge generators capable of creating new information through their use. … Representations are static in relation to what they show and reference. … Knowledge generators have a dynamic open-ended relation to what they can provoke. (65)

Such a distinction has particular resonance in relation to the approach we present here. Rather than thinking of map visualisations as absolute forms of knowledge presenting end results, we place focus on the act of generating maps so that the process is as important as the product, the maps are multiple, and the subjectivity of the critic as both reader and map-maker is taken into account.

This is important because it relates to another undeveloped aspect of working with literature digitally, noted by Martin Paul Eve. He makes the point that traditional literary criticism tends to elide its own process: ‘what is usually of interest to those reading literary criticism is not the process of how the author arrived at the argument but the outcome of the argument’ (Eve, Reference Eve2022: 39). In contrast, Digital Literary Studies is more concerned with how conclusions are reached and even willing to narrate a negative return. From one point of view, this renders digital literary mapping more ‘scientific’, but from another it allows for new ways of ‘doing’ literary (and textual) criticism in the digital domain.

Having briefly outlined a larger need for DH tools and methods to be designed and shaped by the distinctive requirements of the Humanities, the rest of Section 1 looks at three key approaches currently dominant and of relevance to the specific field of digital literary mapping. These are the use of GIS tools when mapping literature onto geographic maps, the interdisciplinary concept of deep mapping as an alternative possible model, and the need for a hybrid methods/multi-scalar approach. Finally, we introduce ‘literary topology’ and explore the inherent subjectivity within chronotopic mapping as a positive.

Digital Literary Mapping and GIS: The Problem of Correspondence

There has long been a fascination with the relationship between literature and place: ‘an impulse to map, to geovisualize the geographies of literature’ (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell and Tally2017: 85), but this has only fully come to fruition in the last ten years with the advent of new tools for digital mapping and visualisation. As a field, digital literary mapping emerges out of a prior subdiscipline within Literary Studies. The concept of Literary Geography originated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its starting point was authorial and concerned with literary touristic interest in place (‘Brontë Country’; ‘Dickens’ London’), which developed by the mid-century into the popular concept of the Literary Atlas. The mapping of authors and texts illustratively onto place in such forms then spawned a far more conceptually advanced mode of literary mapping in the 1990s (led by Franco Moretti) – and out of this came digital literary mapping in the early twenty-first century.

Scholars such as Murrieta-Flores and Martin (Reference Murrieta-Flores and Martins2019) note that different disciplines have engaged with DH at different points in time: fields such as Archaeology made use of digital and spatial tools much earlier than others. One reason for delayed engagement in Literary Studies was the nature of the tools themselves, particularly in their first iteration as complex GIS technologies such as ArcGIS.

In Abstract Machine, Charles Travis opens with the cave paintings of the Lascaux Caves as an example of ‘primal GIS’ (Reference Travis2015: 4), reminding us that the term ‘Geographic Information System’ can be applied to any form of spatial visualisation. In our own time, however, GIS relates specifically to digital software that allows for the visual presentation of geographic information in a range of readable ways. Travis gives a useful technical summary:

A geographic information system, or GIS, provides a digital platform upon which multiple map layers (called shapefiles and rasters) electronically stack on top of each other to create composite images. Each shapefile layer and its attendant data table display unique variables (represented as points, polylines, and polygons). Layers can also be composed of a pixelated terrain or map images called rasters.

In its standard iteration, then, GIS technology draws upon Cartesian and Euclidean geometry and is quantitative in nature – gathering and analysing numerical data and projecting this onto a co-ordinate grid system. Such a model still contains subjective input even when automated (in terms of data selection, correction of computer error in geoparsing, and so on), but the dominant impulse is towards minimising subjectivity. Of course, standard GIS tools can be adapted to more qualitative uses – indeed, the combining of the quantitative and qualitative is a vibrant area of DH.Footnote 1 Still, inherent positivism remains at odds with the more metaphysical needs of the Humanities. As Taylor and Gregory put it:

GIS’s major strength is also its fundamental weakness: the highly quantitative structure that allows us to undertake spatial analysis also depends on translating complex, ambiguous sources into more definite numerical data (such as specific coordinates). This approach also risks stripping the map of its affective meaning.

One effect of this is that GIS methods applied to powerful, even traumatic, experiences can have unforeseen consequences. In exploring the representation of the Holocaust as a geographic as well as historical event, Cole and Hahmann note:

Troublingly, GIS tools have so far proven better suited to working with the documents produced by the perpetrators with their chimera of certainty … than the post-war testimony of Holocaust survivors … [A]dopting GIS tools has tended to privilege understandings of perpetrator space over victim experiences of genocidal place.

In this highly-charged example, the need for alternative approaches is strongly felt.

We can consider such issues further, as they impinge upon the mapping of literary place and space, by looking at two attempts to use GIS for digital literary mapping and at some of the problems that rapidly emerge. The first major digital literary mapping project – A Literary Atlas of Europe (2006–) – took its impulse from the paradigm shift initiated by Franco Moretti when he redefined literary maps, ‘not as metaphors, and even less as ornaments of discourse, but as analytical tools that dissect the text … bringing to light relations that would otherwise remain hidden’ (Moretti, Reference Moretti1998: 4). For this project, cartographers and literary scholars worked together to create a prototype quantitative mapping model for literature with the potential to be rolled out at a large scale (Piatti et al., Reference Piatti, Bär, Reuschel, Hurni, Cartwright, Cartwright, Gartner and Lehn2009). The digital Atlas focussed on three test areas (a lake, a coastal region, a city) with five fictional elements mapped across texts and authors to create a spatial database capable of generating automated maps. The core geometric elements were ‘setting’; ‘projected space’; ‘route’; ‘waypoint’; and ‘marker’. The model attempted to allow for non-place-specific spatial elements in fiction (‘projected space’) as well as for differing degrees of distance from the geographic.Footnote 2

Right from the start, the Literary Atlas identified that ‘the geography of fiction must be characterised as a rather uncertain or imprecise geography’ (Reuschel et al., Reference Reuschel, Piatti and Hurni2009: 6) and stated:

Fictional spaces are artificially created by description in prose by the author. They do not have definite borders, are often hard to localize and shift on a scale between strong and weak relation to the actual geospace. (1)

To allow for this, in visualising ‘setting’, the problem of indeterminacy was presented through colour fading and fuzzy images. For ‘routes’, equally, the multiplicity of options left implicit in a text led the project to create three categories: ‘taken from the text’; ‘plausible’; and ‘interpreted’ (9). Thus, the Literary Atlas rapidly identified a number of unique attributes of literary place and space that were revealed by the challenges of attempting to map it onto the physical world – that is to say, the resistance of literary place to being fixed, not least because ‘a specific feature of a literary space is its numerous gaps’ (Piatti et al., Reference Piatti, Bär, Reuschel, Hurni, Cartwright, Cartwright, Gartner and Lehn2009: 185).

At the same time, a comment such as the one quoted in the previous paragraph concerning fictional spaces makes clear the way in which the project was weighted towards the geographic. A literary scholar would never describe fictional spaces as ‘artificial’ and such a comment is in danger of falling into the ‘referential fallacy’ – mistaking the map for the territory, the word for the thing, and failing to understand that the ‘real’ does not lie behind the fictional, or constitute its ground.Footnote 3 As a result, a major weakness of the project is that it is constantly centred on a desire to be ‘accurate’ and to fix correspondence in a way that is problematic and near-paradoxical:

It is mandatory to determine the identity of the setting: textimmanent names (direct referencing) or names deduced indirectly from other sources or researches (indirect referencing). For example in Thomas Mann’s famous novel ‘Buddenbrooks’ (1901), Lübeck as the main setting is never named. Yet through a couple of hints (Travemünde and the Baltic Sea are mentioned), it becomes evident, that no other town can be filled in. At the same time the level of accuracy has to be estimated.

Here we feel the danger of strongly privileging the known over the represented or imagined – which the act of correspondence to actual sites in the world encourages.

Many of the challenges experienced by the project team can be seen to be created by the nature of the GIS tools being used and their implicit imperatives. What the resistance to representation really tells us is that these tools do not allow Humanists to do what they want, or need, to do with the relationship between literary place and space and real-world geography. In a chapter on ‘Maps and Place’ in The Digital Humanities and Literary Studies Martin Paul Eve sums this up well:

[D]igital mapping approaches demonstrate to us the problems in transposing literary texts, which use their space as narrative structuration devices, onto maps that purport to represent an extra-textual reality. Like all good humanistic inquiry, digital mapping does not simply produce positivistic answers to scientifically framed questions. Because the two – maps and reality, or mapping questions and cartographic answers – do not piece together neatly like a jigsaw. They rather sit in a relationship of mutual tension and productive questioning.

Let’s turn to a second example of relatively early adaptation of GIS software for the mapping of literature: Charles Travis’s attempt to map Homer and Dante onto the map used by James Joyce for Ulysses.Footnote 4 Travis provides a solid authorial rationale, based on Joyce’s famous comment that he aimed to ‘give a picture of Dublin so complete that if the city one day suddenly disappeared from the earth it could be reconstructed out of my book’ (Budgen, Reference Budgen1972: 69) and on the fact that Joyce wrote Ulysses in Paris using a 1904 map of Dublin.

Travis employs the 1904 map as the base layer and argues for a writerly process that combines detailed map knowledge with the development of intersecting narratives:

Joyce used Thom’s directory and map to erect Cartesian scaffolding over the city of Dublin. In this framework, and influenced by Classical Greek and Medieval Italian epic poetry, he stitched together the book’s plotlines. Once he had sewn the fabric of his book together, Joyce dismantled the cartographic structure.

In this example of digital literary mapping, then, the tools are used in two ways: to reconstruct an earlier stage of (cartographic) authorial creative process, and to integrate this visually with other spatial forms from influential intertexts.

Travis’s approach is sophisticated and ambitious. It is informed by Deleuzian theory as well as biographical and contextual knowledge about writerly process and seeks to advance three different forms of ‘interpretive visualisation’ at the same time: ‘hermeneutic (textual and topological), ergodic (mapping alternative narrative paths in a “cybertext”), and deformative (deliberate textual misreadings)’ (Travis, Reference Travis2015: 64). The total version of Dublin, Homer, and Dante combines the verticality of Dante’s layers with the routes of characters across the city and Odyssean journeys (see Figure 1) – these maps are also given in much greater detail as a separate series. Thus, although Travis uses some standard GIS tools, he also combines these with a layered approach that visualises entirely fictional spatial movement. The aims of the visualisation are also therefore multiple:

This GIS model serves three objectives. The first seeks to create a topographical picture of Dublin using the cartographical source material that Joyce used to plot his novel. The second translates Joyce’s ‘cut-and-paste’ and other visual and literary methods into GIS form. The third explores and maps how Joyce narratively and topologically linked various Dublin locations to selected Homeric episodes with symbolic references to Dante’s journey.

Finally, Travis also makes the crucial point that the visualisations are part of a process rather than an authoritative single map.

Figure 1 Charles Travis: Arcscene visualisation of Ulysses in Abstract Machine, 79.

There is much to admire in the creativity and ambition shown here, but also plenty to critique. For example, locating the authority of the intersecting map visualisations for Homer and Dante authorially in Joyce is problematic since it necessarily moves into speculation:

ArcMap and ArcScene helped to create a 3D model that overlaid Homer’s and Dante’s schemas and topologies onto a digitized Thom’s map of Dublin to visualize how Joyce conceptualized the voyages of Bloom and Dedalus.

Do we really know for sure ‘how Joyce conceptualized’ his characters’ journeys? And, if we do, shouldn’t authorial mapping be incorporated explicitly? For the work to convince a literary or textual scholar, the mapping of process should be fully integrated with high-level knowledge of the development of the texts.

A fuller experience of the intertextual interweaving is also needed alongside the visualisations of individual routes (which equate Dublin streets directly with layers in Hell and stages of Odysseus’s journey). This could have been done using digital tools (combining GIS with corpus linguistics) to map and visualise intertextuality much more directly, but also to think about how best to visualise the intertextual space itself. Equally, for the project to be rigorous, if it is concerned with Joyce’s process one might want the base text to be that of draft materials rather than the published text, for each section of the map. This would also potentially introduce a more dynamic spatio-temporality into the visualisation in terms of the gradual building of the modern odyssey across the different spaces of the city.

In their recent book, Taylor and Gregory outline three phases for Digital Humanities scholarship and argue that we are moving into the third of these:

In the first, databases, corpora, and/or techniques are developed to explore the potential of digital methods in advancing knowledge about a particular kind of source. In the second, method or data-led research starts to be conducted using these new resources, with the aim of exploring, explaining and critiquing these new opportunities. A third stage involves moving the humanities back into the foreground by using the technology to develop nuanced responses to applied research questions on topics that are derived primarily from the sources rather than the technology.

When we compare the work of the Literary Atlas of Europe project with Travis’s mapping of Ulysses, the rapid advances made in the use of GIS tools seem to enact the move from phases one and two to three (and do so in less than a decade).

Digital Deep Mapping

An alternative approach to the limitations of standard GIS mapping that is often cited (and could be envisaged for Travis’s work with Joyce) is that of the ‘deep map’. This position emerges as resistance to, or an adaptation of, GIS methods and tools to more creative ways of engaging with place and space. However, deep mapping is a difficult approach to pin down.Footnote 5 It locates its own pre-digital origins in a detailed multimedia presentation of place (PrairyErth) that combined travel writing with interviews, local myths, factual information, and cartography.Footnote 6 Thus, it is a method of mapping with a strong underlying ethos: a desire to tell stories about place, or present place through multiple forms in an inclusive way. Although not originally created for the digital domain, it lends itself to digital mapping because of its inherent cross-generic, interdisciplinary, and multimedia tendencies.

The implication of this for digital tools and methods is perhaps most clearly understood in comparison with traditional cartography. Deep mapping explicitly differentiates itself from both 2D map representations and Cartesian principles, in which ‘an emphasis on absolute space based on Euclidean coordinate systems often frustrates the humanist’s effort to understand how spaces change over time and how spatial relativities emerge and develop’ (Bodenhamer et al., Reference Bodenhamer, Corrigan and Harris2013: 174). In the discipline of History, where deep mapping has so far found greatest traction, it ‘embraces multiplicity, simultaneity, complexity and subjectivity’ and advocates a far more ‘bottom up’ approach: ‘In it we do not find the grand narrative but rather a spatially facilitated understanding of society and culture embodied by a fragmented, provisional, and contingent argument with multiple voices and multiple stories’ (Bodenhamer et al., Reference Bodenhamer, Corrigan, Harris, Bodenhamer, Corrigan and Harris2017: 5).

Deep mapping thus also suggests a particular approach towards its subject which is highly performative and has a ‘processual underpinning’ (Springett, Reference Springett2015: 624). This lends itself particularly to visual and performance art, which may be the best medium for the concept:

Deep maps go beyond description or simple communication, rather they are an enaction of place. They offer a certain type of storytelling that seeks to democratise knowledge, through the use of the map.

Thus, practitioners such as Ian Biggs develop a model of deep mapping as artistic practice focussed on the rich temporal processes in place that can also inform the work of art itself.Footnote 7

Perhaps the best worked-through example of academic deep mapping to date is the Lancaster University project: Geospatial Innovation in the Digital Humanities: A Deep Map of the Lake District (2015–2018) and its resulting publications.Footnote 8 In Deep Mapping the Literary Lake District: A Geographical Text Analysis, Taylor and Gregory provide a convincing model that successfully combines ‘quantitative methods with a detailed understanding of the historical, cultural and geographic contexts in which these texts were written’ (Reference Taylor and Gregory2022: 23). Centred on a textual corpus of Lake District writing, chapters then work across nineteenth- and twenty-first-century concerns seeking to ‘interpret the apparently objective data displayed in GIS through a subjective lens’ (Reference Taylor and Gregory2022: 63). It should be noted, however, that although the book explores these concepts fully, there is no digital ‘deep map’ website produced as an exemplar. Equally, although it engages with the literary, the core textual focus is on travel writing rather than fiction so that the relationship between geographic maps and texts remains relatively unproblematised.

Cultural Geographer Les Roberts’ consideration of deep mapping in terms of diachronic and synchronic relations also seems highly relevant here (Roberts, Reference Roberts2016).Footnote 9 If Archaeology deals (at least primarily) with physical, material layers of meaning, and History with an intermingling of the material and textual, Literary Studies is just as layered but has to handle a more problematic relationship to both geography and the map (as we have seen). A literary work also has multiple temporalities in play that are of equal importance. Diachronically, the work stands in relation to its own past production (acts and sites of writing, pre-text and draft materials) as well as future versions of itself (later revisions, republication in different contexts, etc.). Synchronically, it presents multiple moments of horizontal connection at points of contingent completion or publication that generate reader-reception and response beyond the control of the author. Representationally, the literary world generates its own place and space at different distances from the world according to literary form and with radically varying degrees of representation of external and inner space. Shelley Fisher Fiskin defines such maps as ‘palimpsests in that they allow multiple versions of events, of texts, of phenomena (both primary and secondary) to be written over each other – with each version still visible under the layers’ and one can envisage a rich and complex ‘deep text’ model for a digital edition working in such a way.Footnote 10 Thus, the potential for a highly complex structure of digital literary deep mapping is certainly present, but not yet developed.

With the advent of ‘neogeography’ or non-expert mapping (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell and Tally2017) a set of new tools and methods for Web 2.0 have started to open up mapping to the general public, as well as to Humanities scholars not highly trained in computer programming. Geovisualisation tools release the user from the need to pinpoint a place to a specific location upon the earth’s surface and allow for freer, more experimental, and more self-aware modes of mapping literature onto the historic, or for the combining of 2D and 3D models. Nonetheless, at the time of writing, deep mapping is more theorised than practised (beyond the field of art) and Literary Studies remains sceptical. Les Roberts goes so far as to suggest that deep mapping ‘should be implicit not explicit in its application’ (Reference Roberts2016: 4). In a sense this returns us to our starting point: deep mapping’s resistance to definition. Perhaps it is more about an underlying stance within the Spatial Humanities than it is a method in and of itself.

Quantitative versus Qualitative, Macro- versus Micro-Mapping

In their work on the geography of the Holocaust mentioned previously, Cole and Hahmann describe the experience of scale for those living through the event:

Scale operates metaphorically as a set of Russian dolls (Herod 2010), with the body inside the local, inside the regional, inside the national, inside the continental, inside the global. Survivors tend to move in between these scales in narratives that are spatially (and oftentimes also temporally) dynamic rather than fixed.

They suggest that such complex human experiences can only be visualised and mapped effectively by using a dynamic and multi-scalar mapping model. They conclude by making three crucial points concerning the value of relative mapping using a network model as opposed to the point-based specificity of GIS:

Alongside the possibility of zooming in and out of the scales of narratives, the use of a graph representation allows for the inclusion of the varying degrees of certainty and uncertainty found within humanities sources in the database. … But it is not simply the case that rethinking database design enables us to work with the complexity of the kind of narratives that digital humanists encounter. They also enable us to undertake new forms of analysis from this complex data.

All three of the points made here (the need to zoom in and out; the representation of uncertainty; the two-way learning process in adapting digital tools) are also of vital importance to the mapping of literary place and space. Visualisations need to be able to move between whole text, chapter, page, and paragraph level – as well as to allow for the different spatial experiences of multiple characters, narrators or narratives, and readers – and the spatial indeterminacies and dislocations built into these. Furthermore, the engagement between texts and tools needs to generate new forms of analysis extending easily out of the old. Apart from enriching the Digital and Spatial Humanities, this is also essential if such work is to become a fully integrated element of its core disciplines.

Such a call for macro- and micro-mapping intersects with the prior debate in Digital Literary Studies between ‘distant’ and ‘close’ reading – which crudely corresponds to ‘zooming out’ and ‘zooming in’. In its first major phase (roughly 2005–20), DH focussed primarily on quantitative analysis as a consequence of its origins in Moretti’s call for large-scale ‘literary history’ and his desire to open up Literary Studies to quantifiable methods. This emphasis was also logical, since it made the best case for the new insights offered by computational approaches (i.e. the computer’s ability to read at scale will always exceed the capacities of a human reader). More recently, however, the distant/close reading debate has been accused of creating a false binary between past and present practices. Even so, that binary points to an underlying issue that is harder to dismiss: should Digital Literary Studies be concerned with respecting the uniqueness of the computational tools and thus privilege the new medium allowing it to reconfigure our understanding of the home discipline; or should the discipline be seeking to reshape digital tools and methods to enable integration of more familiar exploration of texts in known ways?

It is telling that, in order to make arguments that prioritise new ways of counting-as-reading over traditional hermeneutics (‘close reading’), the works of literary criticism that are targeted for critique by DH scholars are more than sixty years old. So, Matthew Jockers in Macroanalysis takes issue with Erich Auerbach's Mimesis (1946) and Ian Watt's The Rise of the Novel (1956), while Andrew Piper critiques a metonymic model at the heart of close reading, again using Auerbach (Jockers, Reference Jockers2013: 7; Piper, Reference Piper2018: 7–8). Why is this? Primarily because the current discipline of Literary Studies in the twenty-first century is self-aware, wide-ranging, and highly interdisciplinary. Any recent work of literary criticism will undertake textual analysis in conjunction with cross-disciplinary theory and complex philosophical, social, and ideological ideas. Thus, the reduction of intellectual activity to close reading of the canon (necessary to assert the superiority of distant reading in comparison) can only occur by temporal displacement. To be fair to the discipline, Jockers and Piper should be choosing an influential literary-critical study published post-2000. They cannot do this, because then the evidence base for the ‘before’ to their ‘after’ would not be a narrow close reading of a few canonical texts.Footnote 11

Another key issue in the attacks on close reading is the false presentation of it as if it were a method when it is in fact a skill. In contemporary literary criticism the ability to undertake high-level analysis of a text is simply one key attribute among many (e.g. Derrida was a great close reader, but this hardly defines him). This clarification is important, because it allows for a very different way of integrating DH with the core Humanities subjects, without the need to aggressively redetermine the source discipline. An approach that combines the quantitative and the qualitative should be able to function as another form of interdisciplinarity in which the reading of literary texts in one way and through one frame can be placed alongside the reading of texts in a different way, through another. Admittedly the medium itself is of a different order, but this just makes for a unique interdisciplinary relationship. Our own position therefore is to advocate a middle ground in which each side is open to the other (enlightened cross-fertilisation).

The field of Digital Literary Studies is in a process of recalibration, but the resistant position to distant reading still tends strongly towards identifying quantitative methods as already present within Literary Studies in order to justify this approach at macro- and micro-levels rather than integrating with traditional interpretative practices. In Enumerations, Piper explicitly wants to move on from ‘overly binary models of reading largely untethered from past practices’ (Reference Piper2018: x). But to do this, his study seeks to locate quantitative elements within the core discipline – identifying the ‘building blocks of literary study’ in terms of areas such as ‘punctuation in poetry’, ‘emplotment in novels’, and ‘dispersion of topics’ (3).

For his part, Martin Paul Eve inverts the distant reading model by applying computational methods to a single text (David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas) focussing closely on linguistic patterns and shifts that are otherwise not obvious when reading. The analyses enabled by Eve’s ‘Computational Formalism’ (Eve, Reference Eve2019: 21) work ‘through a type of deformative reconstruction, they make clear something that was directly under our noses but that still required elucidation’ (19). However, the nature of this ‘close reading’ – of variants across published texts or genre identified through ‘microtectonic linguistic shifts’ and stylometry (22) – feels very different from the disciplinary norm. Eve’s position – emphasising, on the one hand, that distant reading existed within Literary Studies long before computers, and, on the other, that close reading can be undertaken by a computer, not just a literary critic – thus makes the case for automation at macro- and micro-levels, but the nature of the ‘close reading’ is really just distant reading on a small scale. Thus, such approaches helpfully seek to make a bridge between the home discipline and DH, but not between qualitative and quantitative methods. Our position is different from these, since we do not feel the need to negate or redetermine long-standing interpretative activities in the home discipline at the expense of DH, but seek to combine the two – folding past methods into the present and future.

A multi-scalar model is another way of bridging between traditional Literary Studies and Digital Literary Studies and between verbal and visual needs. As English and Underwood make clear, in their introduction to a special issue on the subject, Literary Studies has always been in part ‘a drama of competing scales’ and close reading can itself be viewed as an example of ‘scalar contraction’ (Reference Underwood2016: 278) which reached its peak in the 1970s before an opposing expansion into a ‘crisis of largeness’ (Reference Underwood2016: 281). Jay Jin develops such ideas by drawing out the ways in which close/distant is also synecdoche/metonymy and makes the helpful point that perhaps the real threat of close reading is that ‘closeness … marked a synecdochic relationship that removed the need for scale altogether’ (Reference Jin2017: 112). The DH relationship between macro and micro, or quantitative and qualitative, analysis has also tended to be sequential – from counting to reading, from information to interpretation – but this does not have to be the case. Jin’s suggestion that ‘[I]nstead of complementarity or linear sequence, one can conceptualize a recursive relationship between “close” and “distant”, a continual back-and-forth’ (Reference Jin2017: 116) is one that we embrace: an iterative approach.

In an article concerned with macro-/micro-analysis for the Spatial Humanities specifically, Taylor et al. provide a detailed account of a ‘multi-scalar’ approach that works in such a way. Exploring soundscapes in the Lake District, the team first uses computational macro-analysis to identify texts from across the entire corpus, which particularly focus upon sound; then read these texts closely, before undertaking a second sweep for emerging concepts such as ‘echo’. This circular structure allows for more traditional hermeneutic activities to be combined with computational (see also Bushell et al., Reference Bushell, Butler, Hay and Hutcheon2022a, Reference Bushell, Butler, Hay and Hutcheon2022b). An iterative approach forms the basis for the topological method as it is fully developed in relation to fictional place and space for the rest of this Element and lies at the heart of our method.

Literary Topology and Chronotopic Mapping

Topology releases the mapping of spatial meaning from the cartographic. It offers a simpler alternative to using a full GIS apparatus and generates a different kind of map. As we have seen, GIS is concerned with a Cartesian map model based upon accuracy to points on the world’s surface. Topology is centred upon interconnections between the elements mapped, but not necessarily with their correspondence to anything else (though a topological map can still be layered onto the real, or combined with GIS). The topology is still a mathematical model, a generated algorithm (and it functions as an underlying element of complex GIS tools such as ArcGIS). But we can also adapt its use to non-scientific ends and use it to pursue interpretative questions in more visually accessible ways that are inherently more suited to the needs of the Humanities.

A topological model is one in which all elements within a contained totality are related to each other in a way that may change across the whole. Not only that, but it can be anchored to the real as needed, yet also move beyond it if place becomes internalised in memory, dreams, fantasy, dislocation, or distortion. The primary focus is on ‘shape, connection, relative position compared with that of geometry (or geography) which are about more rigid notions such as distance angle and area’ (Earl, Reference Earl2019: 2–3). It is perhaps worth noting that this alternative approach for digital literary mapping was always implicitly present in Moretti’s own early work where he observed that ‘geometry “signifies” more than geography’ (Reference Moretti2005: 56, italics original).Footnote 12

In a rich paper on the potential of topology for literature, Piper argues that the forms of topology enabled by an electronic environment represent a paradigm shift in terms of the reader’s relationship to language as ‘a form of action rather than expression’ so that ‘topology encourages us to re-encounter, anew, the visuality of reading’ in a way that ‘alters our visual and cognitive relationship to the text’ (Piper, Reference Piper2013: 377). He concludes:

Reading topologically is an entry into the knowledge of scale and knowledge as scale. Instead of the absolutes of distant or close, we should be thinking in terms of scalar reading. (382)

What is in play here is a part–whole relation that allows for an easy slippage across and between visual and verbal forms.

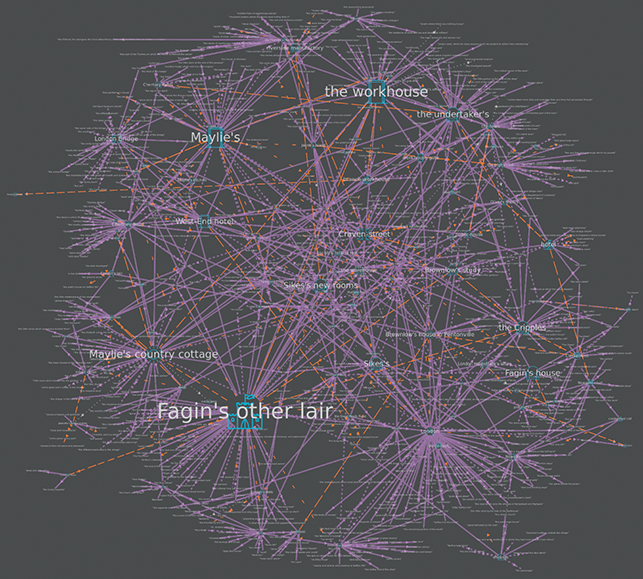

A topological approach emerges out of the adaptation of social network theory to Literary Studies. There have been various attempts to adapt the use of a graph network for literature over the last fifteen years but all prior efforts have been centred upon relationships between characters within a text, rather than seeking to map places and spaces in the narrative (as we do in the Chronotopic Cartographies project). Following Rydberg-Cox’s work on Greek drama (Reference Rydberg-Cox2011), much of the research has been centred on different dynamics between character groupings within the whole (single central character; two factions; clusters; anomalies). While Rydberg-Cox’s work uses the stage, and appearances on it by actors, to determine points of contact, the work of Elson, Dames, and McKeown is centred upon an attempt to ‘derive the networks from dialogue interactions’ and includes automated ‘components for finding instances of quoted speech, attributing each quote to a character, and identifying certain characters who are in conversation’ (Elson et al., Reference Elson, Dames and McKeown2010: 138). A similar model is explored by Moretti in his Stanford LitLab pamphlet ‘Network Theory, Plot Analysis’. Here, Moretti draws a direct equivalence between plot and network – although plot is determined in terms of character rather than narrative: ‘A network is made of vertices and edges; a plot of characters and actions: characters will be the vertices of the network, interactions the edges’ (Moretti, Reference Moretti2011: 2).

In contrast to such pre-existing network models, our chronotopic method is centred upon spatio-temporal meaning across the narrative and thus allows greater space for the exploration of structure, narrative, event, and plot, as well as of spatiality (human lived experience) represented within this. A full account of the technical method is provided in the Online Methodological Appendix, but it can also be summarised briefly here, along with key tables.

A bespoke spatial schema for chronotopic mapping was developed by the team and applied manually to texts to enable graph generation out of them.Footnote 13 A text is marked up by chunking out sections in terms of both location and chronotopic identity and this generates the nodes of the graph topology. The identity of the chronotopes derives primarily from the account given by Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin ([Reference Bakhtin and Holquist1937], 1984) but with the necessary additions of ‘distortion’ and ‘metanarrative’ (see Table 1). Nodes are then connected to each other by different forms of connection allowing for direct, indirect, and internal movement (see Tables 2 and 3). Within a node, place names (toporefs) are also identified with varying levels of distance from representational place.

Table 1 Chronotopic symbols and descriptions

Table 2 Connection types and styles

Table 3 Chronotopic Cartography colour key

The marked-up text as an XML file is processed using a series of functions written in the Python programming language then exported as a gexf. file and imported into Gephi, a standard tool for visualising and analysing graphs (see Online Methodological Appendix for a full account). The program generates not a single map but a map series with different aspects of spatio-temporal meaning prioritised in each (see Table 4). A force-based algorithm (ForceAtlas 2) generates the shape of the visualisation in black and white. Finally, the topological form is exported as a graphml.file for final visual styling in colour with names and symbology in Adobe Illustrator. The final visualisations can be presented with curved or straight connections as desired.

Table 4 Map types generated from the mark-up

| Map format | Description |

|---|---|

| Complete | A full map of a text showing the topoi (nodes), their associated toporefs (place names referenced also as a node), and the connections between them (arrowed lines) |

| Topoi | This shows the topoi (framenames) and the connections between them privileged over the chronotopes and without the associated toporefs |

| Syuzhet | This shows the topoi and their connections as they appear sequentially across the text in the order in which the tale is told |

| Fabula | Corresponding to the ‘Syuzhet’, the ‘Fabula’ map shows the topoi and connections in the order in which events actually occurred (not the order as told) |

| Topoi and chronotopic archetypes | This shows the relationship between the topoi and the underlying chronotopic types. For many texts this graph appears as disconnected clusters. However, where topoi change chronotope over the course of a text when a place changes identity (e.g. an ‘Idyll’ becomes a ‘Castle’), the clusters become interlinked |

| Chronotopic archetypes and toporefs | This shows the relationship between the core chronotopic form and the toporefs nested within them |

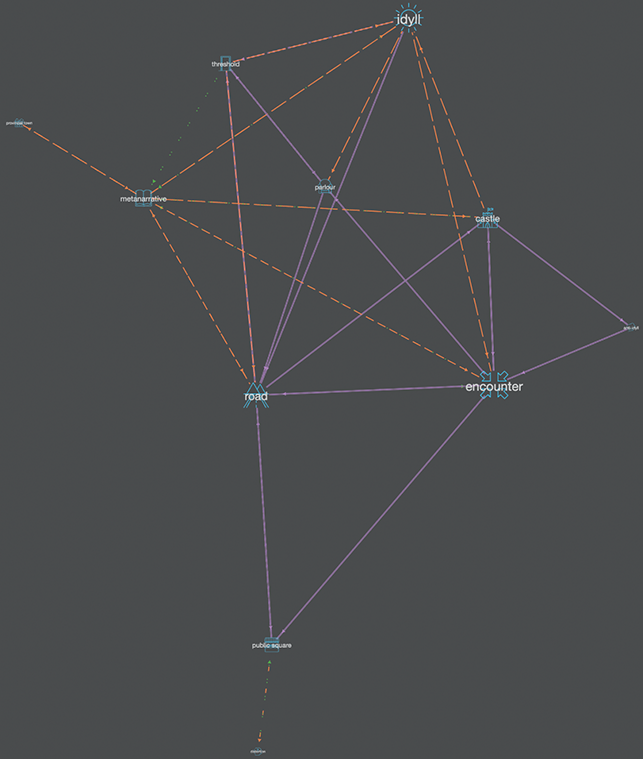

| Deep chronotope | This is the simplest map to understand. It represents each chronotope as a single node, with the scale reflecting the percentage of the text dedicated to each and how they relate to one another |

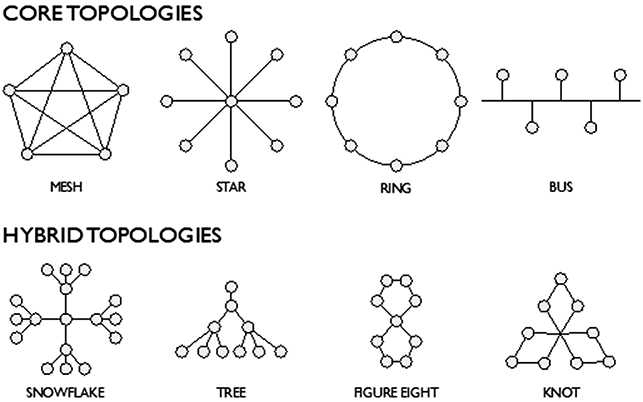

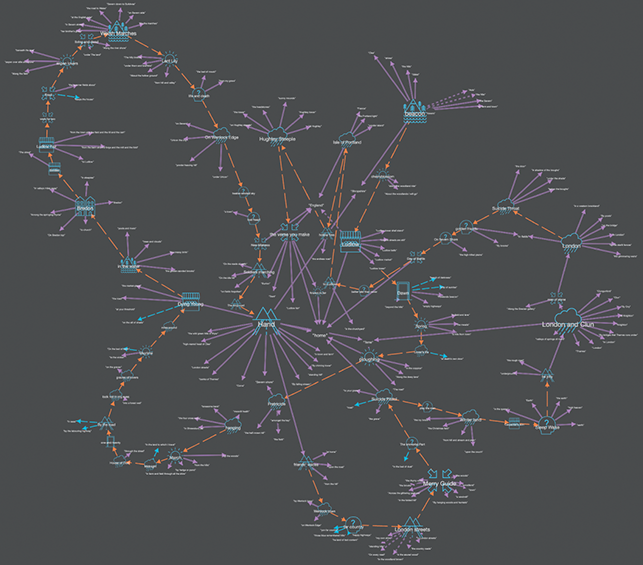

What emerged from visualising texts as graph networks was a variety of topological shapes that essentially provided a ‘map’ of the underlying spatial form of the narrative (see Figure 2). The base topologies of ‘Mesh’, ‘Star’, ‘Ring’, and ‘Bus’ also sometimes combined to form more complex entities such as ‘Snowflake’ or ‘Figure of Eight’. As comparable forms began to emerge across texts, the team realised that if we could find a way to ‘read’ the topological forms in relation to narrative structure and meaning, then an integrated visual-verbal method for analysis would follow from this.

Figure 2 Topological forms

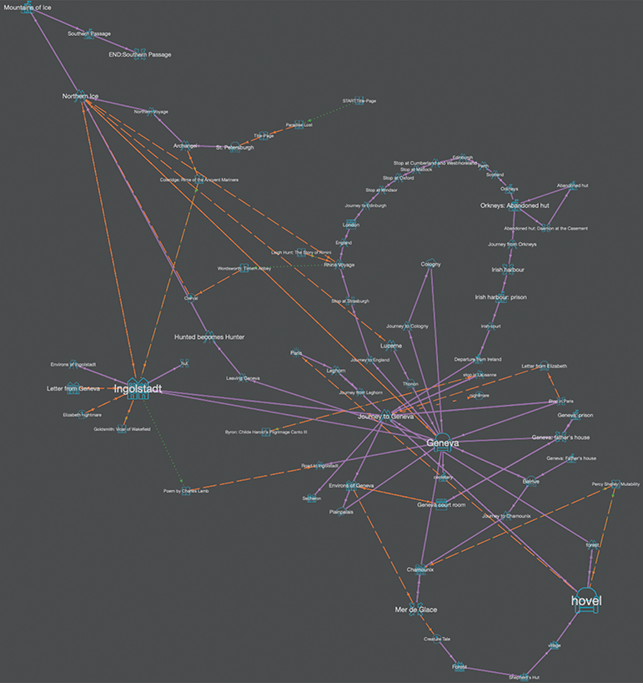

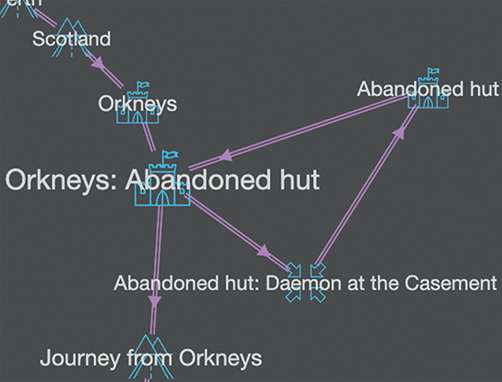

It is worth looking briefly at an example to understand the comparative potential of literary topology more fully. In a ring topology, a circle is formed in which each node is connected only to the two nodes on either side of it. What this suggests, as a spatial form for literature, is a strong linearity within the narrative, or a clear journey out away from home and back. This ring form appears very distinctively as a ‘Big Wheel’ in the Topoi map for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (Figure 3).Footnote 14 Here it relates directly to the spatial practices of Victor Frankenstein as narrator and strongly emphasises his movement as ‘touristic’ for much of the narrative after his meeting with the Creature on the Mer de Glace. Victor sets off on a Grand Tour of Europe with his friend Clerval, that is really a trip to the remotest point (an abandoned hut on Orkney) to try and make a mate for the Creature, at his command (shown top right as a small triangle off the loop).

Figure 3 Topoi map for Frankenstein showing ring topology.

So, in the case of Frankenstein, a series of stops at popular tourist destinations on that ring (e.g. Oxford; Matlock; and Cumberland and Westmorland) is actually a driven trajectory that ultimately goes round on itself and leads nowhere. This also points to deeper conflicting motives in Victor himself and multiple levels of denial about his own actions and responsibilities for them. In his explanation for the tour, Victor deliberately misleads his father: ‘I expressed a wish to visit England; but, concealing the true reasons of this request I clothed my desires under the guise of wishing to travel and see the world’ (Shelley, [Reference Shelley and Hunter1818], 1996: 109). The given reason (to himself) for Victor’s overtly elaborate movement is to hide his motivation from his family. But the true reason is to delay the inevitable. Thus, although the spatial dominates, the underlying motivation is temporal.Footnote 15 By the end, the entire structure functions as a kind of parody of the whole purpose of undertaking the Grand Tour that should refine the gentleman and turn the boy into a man: Clerval is dead and Victor’s future is doomed. Here, visualising the text proves extremely effective in revealing spatial tensions.

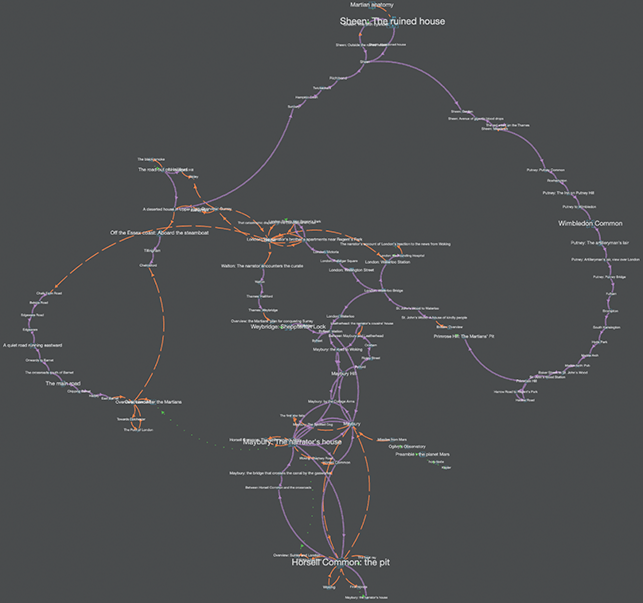

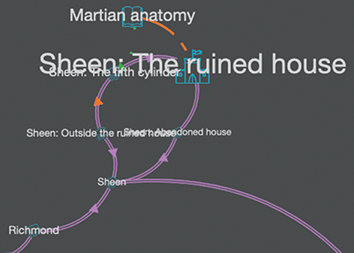

Multiple ring topologies also appear in the Topoi map of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds (see Figure 4). The largest of these (top right) concerns the narrator’s attempts to survive a Martian invasion by fleeing the capital. He moves through specific areas around central London (Hampton Court; Twickenham, Richmond) and eventually back through Wimbledon to Waterloo Bridge, right in the centre of the city. At the top of the loop, in a way directly comparable to Victor’s, a small sub-loop occurs at ‘Sheen: the ruined house’ where the narrator is trapped underneath a Martian invasion pod that has landed on top of him (see Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 4 Topoi map for The War of the World showing multiple rings.

Figure 5 Detail from Frankenstein.

Figure 6 Detail from The War of the World.

We would not normally read these two texts together since they are not of the same literary period or genre. However, when we do juxtapose them – led by the underlying topological form – we can see that actually they do have quite a lot in common. For example, in both texts human motives, actions, and movement are extreme, driven by strong external force – which is what generates the ring topologies. The nature of that external agency is hostile and alien, resulting in forms of movement by compulsion and against the will of the narrator. This is in strong contrast to the power of the spatial catalysts themselves. In Frankenstein, the Creature seems to appear and disappear at will and can travel and inhabit the most remote regions; in The War of the Worlds, the Martians are (initially) immobile but even in this condition are all-powerful (the narrator is forced to remain hidden at the ruined house in Sheen). Taken even further, we can see that grouping texts according to topology rather than to period or genre might create an entirely alternative way of spatialising literature or of reading texts through their spatial forms.

Valuing Subjectivity: A Shropshire Lad

We want to conclude this first section of the Element by considering the value of manual versus automated mark-up and of foregrounding inherent subjectivity within digital literary mapping, because this is crucial to the larger argument concerning a different way of doing things for the Humanities. Privileging manual, subjective mark-up goes directly against a dominant DH desire to automatise reading processes in the Humanities (using tools such as Named-Entity Recognition, Natural Language Processing, and so on). The whole rationale for ‘reading’ in and through a computer is to undertake tasks beyond the capacity of a human reader. This is why the argument for scale (and thus ‘distance’) is so powerful. But a desire to find ways of applying a fully automated model to a subject like Literary Studies assumes a singularity of meaning, or at least an easily defined spectrum. This is, again, fundamentally at odds with the object of scrutiny (complex language) which, by its very nature, is resistant to the reduction to singularity. Thus, rather than seeking to drive towards an absolute, fully automated method we suggest the need for a counterbalancing force that seeks to uncover the implicit subjectivity held in that supposedly objective process.

Is there anything wrong in admitting that each individual coder will generate a subtly different map? When we code manually, and in a way that allows room for the subjectivity of the coder in relation to the text, the same text can produce different visualisations through the mark-up. Subjective decision-making is an innate part of coding and the more complex and rich the text – as for the field of Literary Studies – the greater likelihood there is of variation. This is only a problem if the goal of digital literary mapping is to create universal automated tools with the aim of producing the same results for any user. If the purpose of the exercise is to create digital tools that can be integrated with textual criticism to create complex and multiple interpretations, then this is surely unproblematic. Each critic will come up with a distinctive reading, so why should it not be the case that each map-maker comes up with a distinctive map form?Footnote 16

In the Chronotopic Cartographies project, the spatial schema requires the coder to chunk out the text according to its chronotopic identity, but this identity is far from absolute. Certain chronotopes such as ‘threshold’, for example, are not absolutely determined and could easily be defined in different ways. Equally, chronotopes are themselves innately dialogic. Deciding where one chronotopic identity ends and the next begins is another subjective judgement. In the course of coding literary time-space we also found that prior familiarity with the text was essential (it was far more difficult to make such choices for a text that had not been read before). This suggests that the act of coding is itself interpretative, involving a particular kind of anticipatory momentum.

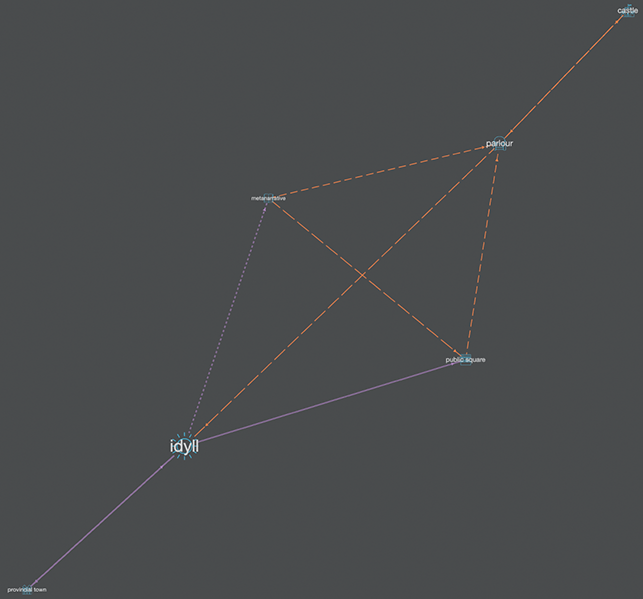

The example we end with here – A. E. Housman’s poem A Shropshire Lad – displays the subjective judgement of two different coders using the Chronotopic Cartographies schema with strongly distinctive resulting visualisations.Footnote 17 Across the map series for this text, some of the maps made by the two coders look quite similar (e.g. the underlying Deep Chronotope map), while others look very different (Complete map, Topoi map, and Syuzhet map). For the rest of this section we seek to explore why this might happen, how interpretation acts upon mark-up if the base text is not simply treated as ‘data’ by a computer, and why this might be worth retaining or playing off against automated results.

Some context is required. A Shropshire Lad was published by Housman in 1896. The long poem consists of sixty-three short simple lyric sections written in a loose ballad form. A strong sense of mortality underlies the whole and this sense of loss, combined with its depiction of the composite ‘lad’ of the title in the full flush of youth (shepherd; farmhand; new recruit; soldier; doomed youth), made the poem extremely popular during the First World War (which it strangely anticipated). As Nick Laird puts it: ‘if Housman were an emotion then, he would be longing’ (Housman, [Reference Housman and Burnett1896] Reference Housman and Burnett2010: xiv).

In the text, person and place are bound together but temporality is often at odds with spatiality. It is as if the narrator is out of step with his own time. So place is both real and remembered, lived and allegorical, present and past, as in the distilled perfection of poem XL:

The poem’s sense of place means that, across the whole sequence, it repeatedly circles away and back to key sites (Wenlock Edge, Ludlow Tower, and Bredon Hill) in a way that lends itself to the musical treatments it has received by Vaughan Williams and others. At the same time, this circular structure is offset by a model of accumulation. Housman himself described the writing of poetry as cumulative: ‘a secretion … like turpentine in the fir … like the pearl in the oyster’ (Housman, [Reference Housman and Burnett1896] Reference Housman and Burnett2010: 255). He continues:

As I went along, thinking of nothing in particular, only looking at things around me and following the progress of the seasons, there would flow into my mind … sometimes a line or two of verse, sometimes a whole stanza at once, accompanied, not preceded, by a vague notion of the poem which they were destined to form part of.

So we might say that the structure of A Shropshire Lad inherently holds within it two different ways of responding: in terms of an accumulation of small scenes and moments that add up to more than the sum of their parts, or as a timeless whole, with motifs flowing and repeating across it.

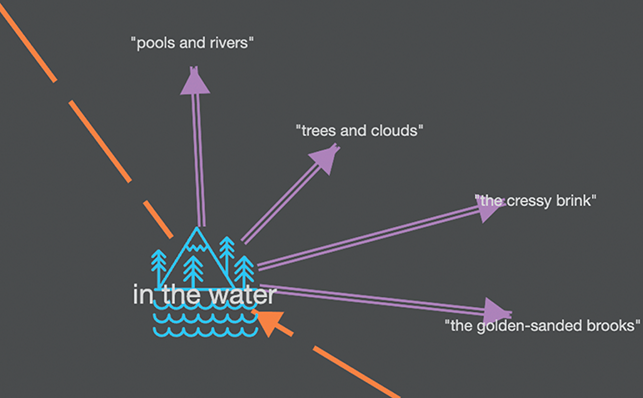

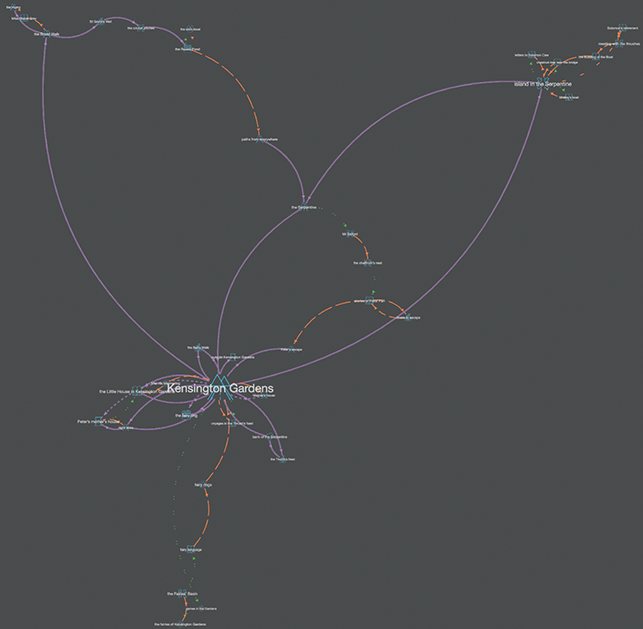

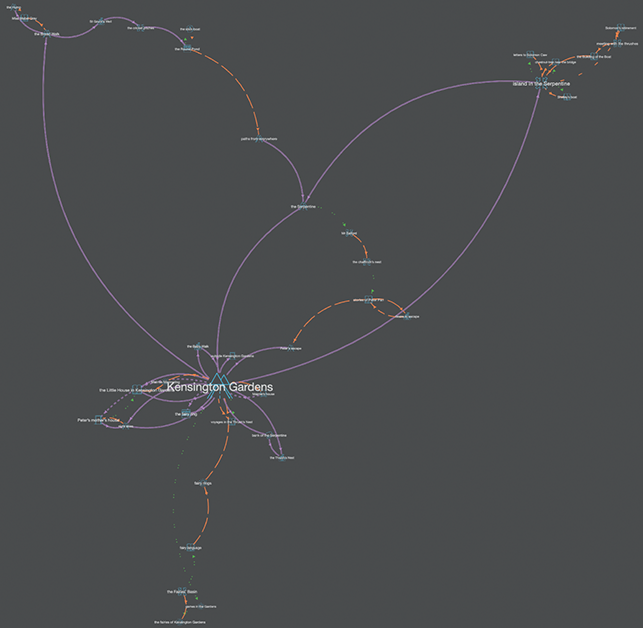

When we turn to the decisions made by each coder, resulting in dramatically different visualisations, we can see this doubleness in play. Perhaps subconsciously Coder 1 (Bushell) felt a greater need to respect the poem’s underlying compositional history, whereas Coder 2 (Butler) responded more directly to the experience of reading the published text. At any rate, Coder 1’s maps treat each short poem as a separate ‘place’. On the butterfly form of the Complete map (Figure 7) this results in small space-specific clusters for particular poem sites. The effect of her mark-up and map ‘style’ is to create small spatial clusters around the dominant topoi that almost read as poems themselves and form loops of connected meaning. So, for example, ‘in the water’ contains ‘pools and rivers’, ‘trees and clouds’, ‘the cressy brink’, and ‘the golden-sanded brooks’ (see Figure 8). Where the underlying chronotope is internal and thus of the mind (distortion), this is felt even more strongly, as if the actual places spring from the imagination. Perhaps the best example of this is ‘Far Country’ as a poem about the narrator’s own youth with the related toporefs of: ‘yon far country’, ‘those blue remembered hills’, ‘the land of lost content’, and ‘happy highways’ (see Figure 9).

Figure 7 Complete map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 1).

Figure 8 Detail from Complete map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 1).

Figure 9 Detail from Complete map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 1).

In contrast, Coder 2 coded the text as if it were a single continuous whole by determining universal spatial areas (see Figure 10). The map shows the coalescence of several conceptual representations of Shropshire with greater and lesser degrees of specificity. Names for chronotopic spaces reflect the poem’s spatio-temporal identity with a sense of the real being rendered abstract: ‘Somewhere in Shropshire’, ‘Shropshire County’, and ‘Spaceless Thoughts’.

Figure 10 Complete map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 2).

The Syuzhet maps (showing the order of events as narrated) are the point at which the two coders are most divergent (see Figures 11 and 12). Coder 1’s unusual map form is created by the fact that, for her, the poem moves forward in a series of steps which create a chain of linkage but represent distinct moments in time, suspended as linked memories. The figure S (‘S’ for Syuzhet?) is a pleasing coincidence created by the graph algorithm. In Coder 2’s Syuzhet map, despite all the place specificity of the poem, ‘Spaceless Thoughts’ lie at its heart. The poem’s structure is visualised as a series of interconnected and intermingling memory pockets expressed through a narrator who lies outside the spaces and times being recounted.

Figure 11 Syuzhet map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 1).

Figure 12 Syuzhet map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 2).

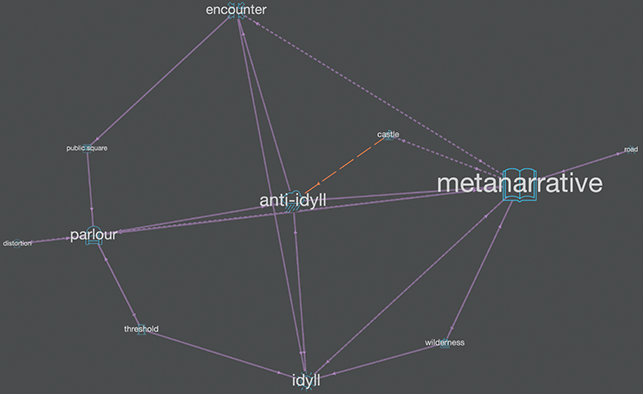

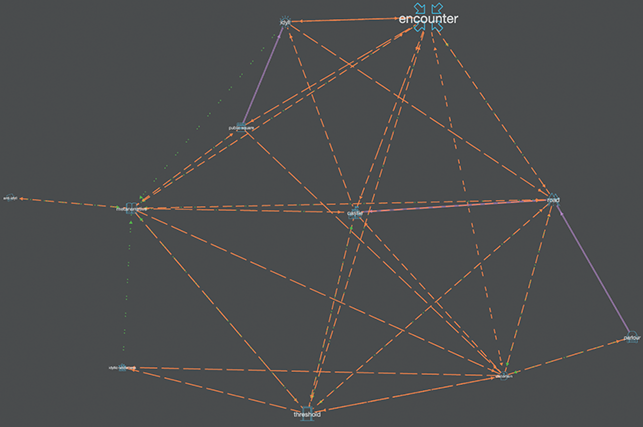

One other map that emerges as highly distinctive is that which shows the connectedness of the underlying chronotopes (see Figures 13 and 14). Although Coders 1 and 2 identified similar deep chronotopic structures beneath the poem, Coder 1’s privileging of the poetic spaces of each mini-text within the whole generates the hybrid topological form of a snowflake structure with each underlying chronotope floating separately. This is because each location is assumed to only ever relate to one spatio-temporal form. Here the anti-idyll predominates, with eighteen frames linked to this chronotope. The sense in which the imagination of the narrator/persona determines the mood and content is also felt in the dominance of both anti-idyll and distortion. In Coder 2’s comparable visualisation, places are far more dynamic in relation to the chronotopes because one place changes its chronotopic identity across the whole. The idyll form again predominates. But now ‘Wenlock Edge’ is both idyll and anti-idyll, while ‘Shropshire County’ is at different times an idyll wilderness, an idyll and ‘a remembered place’. Again this reflects a subjective judgement about the nature of spatiality in relation to poetic form.

Figure 13 Chronotopes and Topoi map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 1).

Figure 14 Chronotopes and Topoi map for A Shropshire Lad (Coder 2).

We have chosen to conclude Section 1 with this example since it so clearly illustrates the point we seek to make: that when we value the process as well as the product of map-making then multiplicity and difference in the maps generated by two coders (marking up manually from the same text) is not something to be hidden or silently omitted. However, we also acknowledge that this raises further questions. We have shown how different choices in manual mark-up can result in very different visualisations; but what of the point of connection between text and image – the underlying algorithm that generated the maps?

In Gephi, four different types of algorithm emphasise different features of the topology (differences, complementarities, ranking and geographic repartition). For the project, the team used the Gephi algorithm ‘Force Atlas 2’ as standard, because it was designed to ‘spatialise small world, scale-free networks’ and emphasise complementarities. There was a logical reason to choose this algorithm for this task, but it was still one choice amongst three force-directed algorithms (Force Atlas, Fruchterman-Reingold, and Yifan Hu).

If we generate the Complete map for A Shropshire Lad using each algorithm in Gephi (see Figures 15–17), we can see that Force Atlas and Yifan Hu produce similar forms but Fruchterman-Reingold is radically different (because it ‘stimulates the graph as a system of mass particles’Footnote 18). This reminds us that the nature of the algorithm bears directly upon interpretation and that it is essential to have a good understanding of the point of handover from human to machine.

Figure 15 Complete map for A Shropshire Lad using Force Atlas 2 in Gephi.

Figure 16 Complete map for A Shropshire Lad using Fruchterman-Rheingold in Gephi.

Figure 17 Complete map for A Shropshire Lad using Yi Fan Hu in Gephi.

As any cartographer knows, the most important skill in making a map is the act of selection – indeed, this is what allows the movement of critical cartography to read against the map in terms of what is not shown/what is hidden. This creates a paradox in which for the map to be of use it must always be a partial misrepresentation. The same is true for digital literary mapping. If every visualisation were displayed in every possible variant, the information would be overwhelming. We might say that just as a literary critic can choose those passages from a text which best support the reading being advanced, so the digital literary mapper can select the most telling map. But at the same time, in both cases, there is a danger of distortion by omission. At the very least we need to be aware of this.

2 Back to Bakhtin: Understanding and Applying a Chronotopic Method

We cannot help but be strongly impressed by the representational importance of the chronotope. Time becomes … palpable and visible. … An event can be communicated, it becomes information, one can give precise data on the place and time of its occurrence.

Section 1 established a larger context for literary mapping in the digital domain and the need for new tools and methods for DH scholars that can meet the complex demands of the object of study. Section 2 focusses on the usefulness of mapping time and space in a combined way for literature through the concept of the chronotope using tools created for the Chronotopic Cartographies project. The concept is derived from the work of Russian theorist, Mikhail Bakhtin. The first half of this section makes clear the degree to which the digital method is indebted to his account of the chronotope in his famous essay, ‘Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel,’ and the usefulness of this in providing a new way forward for digital mapping more broadly.

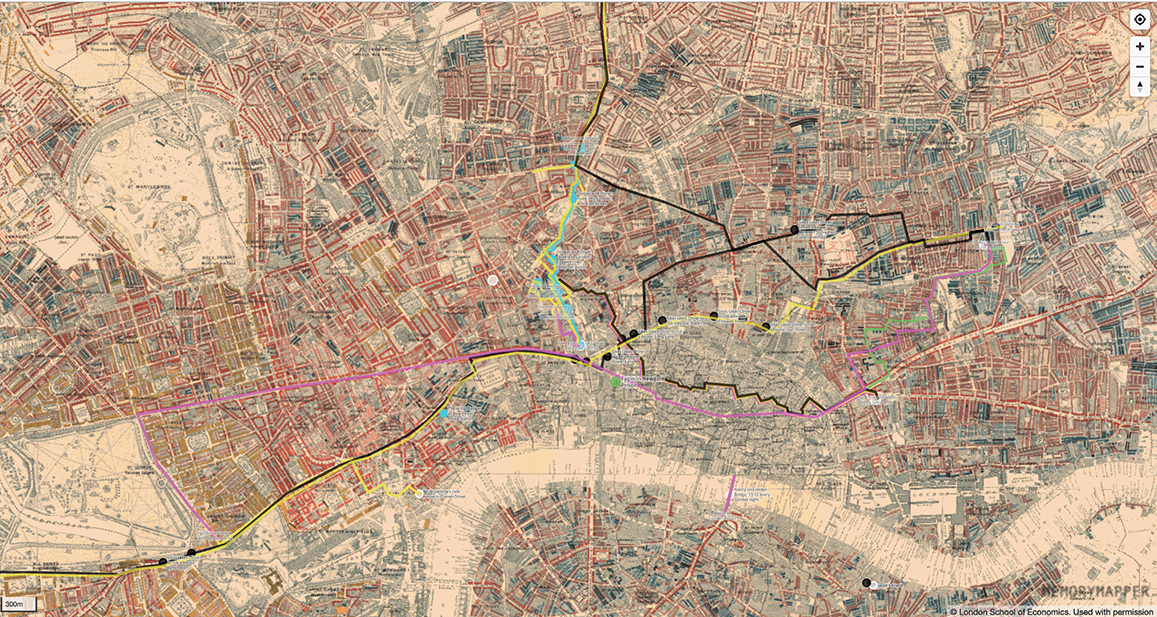

At the same time, in this section we explore the challenge that literary realism presents to digital literary mapping by adopting two approaches to Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. We map realism both in the way it obviously invites – by absolute mapping onto the real with literary place treated as correspondent – and by mapping chronotopically using graph topologies generated out of the text. We do so in order to highlight the problems involved when assuming direct correspondence between the geographic and the fictional but also to show that absolute and relative forms of mapping are not mutually exclusive.

Why Go Back to Bakhtin?

At the close of his well-known essay on ‘Forms of Time and of the Chronotope’, Bakhtin reasserts the fundamental importance of time and space for literature:

[meanings] must take on the form of a sign that is audible and visible for us (a hieroglyph, a mathematical formula, a verbal or linguistic expression, a sketch). Without such temporal-spatial expression, even abstract thought is impossible.

It is only through visualisation, by making the abstract material, that spatio-temporal meaning can be fully understood. Such a statement anticipates and to some extent validates the literary mapping approach adopted by the Chronotopic Cartographies team. In his essay (and in many other writings stretching over a fifty-year period) Bakhtin set about devising an alternative view from that of his fellow formalists, opposing the idea that the Humanities can best be understood by means of larger patterns and structures and seeking to develop a model generated out of the text and contextualising literature through the filter of real-world constructs.

Bakhtin consistently approaches the text (form and content) in terms of what is unique to literature rather than to linguistics or philosophy. The text is not reduced to a reflection of something else. This is why, in our view, the chronotope is a more useful and pliable model than other time/space combinations, such as Lefebvre’s tertiary space (Reference Lefebvre1974), Foucault’s heterotopia (Reference Foucault1986), or Harvey’s time-space compression (Reference Harvey1989). Unlike these models, the chronotope is specifically identified with literature and the unique spatio-temporal constructs it generates.

Ostensibly, the emergence of the chronotope could be seen to correspond to a more general turning towards space at the end of the twentieth century. However, it is missing from many influential accounts by major commentators such as Soja, Jameson, and Massey, none of whom mention it explicitly.Footnote 19 As Susan Friedman explains, ‘Bakhtin’s sense of the mutually constitutive and interactive nature of space and time in narrative has largely dropped out of narrative poetics’ (Reference Friedman2008: 194). One reason for this oversight may be that critical history has tended to dwell upon the temporal elements of the chronotope. Bakhtin himself prioritises the temporal over the spatial – after all, the title of his essay is ‘Forms of Time’ not space and he asserts that ‘the primary category of the chronotope is time’ (Bakhtin, [Reference Bakhtin and Holquist1937] Reference Bakhtin and Holquist1984: 85). In Bakhtin’s account, protagonists are defined by their ‘eventness’, and his analysis is influenced by the temporally orientated narrative distinction between fabula/syuzhet of Russian Formalism (chronological order of events versus order of the narrative as related).

From this perspective, the chronotope appears as a confirmation of the very impulse against which the spatial turn was turning. What is elided, however, in the accounts of Bakhtin’s chronotope that focus on time at the expense of space, is the fundamental interconnectivity of the two. Friedman makes this point well in her Kristevan reading of Bakhtin’s ‘spatial tropes’ where she explicitly rejects reading for either time or space alone (1993: 12–23). The chronotope, in Friedman’s understanding, is valuable for its delineation of narrative axes which allow the reader – occupying the vertical axis – to interact with the text’s horizontal axis, connecting these times and spaces inside and outside the text. Our method, which moves iteratively between the process of reading and mapping texts chronotopically and the product of synchronic visualisations, shares this intersection of the linear and the simultaneous.

One person who certainly does recognise the value of Bakhtin in relation to space is Franco Moretti. He cites Bakhtin only a few times in Atlas of the European Novel but those moments are worth close consideration. In a discussion of spatial organisation (centres and margins) in the historical novel, Moretti quotes Bakhtin directly (embedding the latter’s words within his own):

The chronotope in literature has an intrinsic generic significance. It can even be said that it is precisely the chronotope that defines genre and generic distinctions.

Each genre possesses its own space, then, – and each space its own genre: defined by spatial distribution – by a map – which is unique to it.

As the quotation he provides makes clear, the inherent power of Bakhtin’s model lies in the way in which it spatialises genre. Moretti comes directly out of this to develop his own approach in terms of the explicit visualisation of those spatial elements by means of mapping activities ‘as analytical tools: that dissect the text in an unusual way, bringing to light relations that would otherwise remain hidden’ (Reference Moretti1998: 3). As Moretti himself explicitly states, ‘Bakhtin’s essay on the chronotope … is the greatest study ever written on space and narrative, and it doesn’t have a single map’ (Reference Moretti2005: 79). In other words, there is a sense in which Moretti’s maps are nothing more nor less than a visualisation of the theory of the chronotope.

For example, Moretti’s focus on the picaresque novel looks directly back to Bakhtin’s description of the development of the novel in relation to the chronotope of the road. If we look at what Bakhtin himself does, we find that he historicises and identifies changing usage and meaning of ‘the road’ over time and across generic categories. He tells us that ‘in folklore a road is almost never merely a road, but always suggests the whole, or a portion of “a path of life”’, and he contrasts this with an earlier Greek romance model where ‘it was merely a mannered enchaining of coordinates both spatial (near/far) and temporal (at the same time/at different times)’ (Bakhtin, [Reference Bakhtin and Holquist1937] Reference Bakhtin and Holquist1984: 120). Later, when he returns to this subject in his ‘Concluding Remarks’, Bakhtin combines the predominantly spatial form of the road with the temporal form of ‘the encounter’. He explains:

Encounters in a novel usually take place ‘on the road’. The road is a particularly good place for random encounters. On the road … the spatial and temporal paths of the most varied people … intersect at one spatial and temporal point. … On the road the spatial and temporal series defining human fates and lives combine with one another. … Time, as it were, fuses together with space and flows in it (forming the road).

Moretti takes Bakhtin’s account, acknowledges his influence indirectly by presenting a quotation from Bakhtin on the same page as the map, and then makes his own map that partially visualises the chronotope in relation to a particular sub-genre. His immediate aim is to contrast the pilgrimage route to the North with that of the picaresque novel, to make the point that ‘these novels turn their back to the pilgrims of Camino de Santiago for roads that are much more worldly and crowded and wealthy’ (Moretti, Reference Moretti1998: 48). The map makes this clear (see Figure 18). The secondary aim (also from Bakhtin) is to make the point that the novel form and genre itself emerges out of the rhythm and pace of the road:

A slow and regular process, daily, tiresome, often banal. But such is precisely the secret of the modern novel … modest episodes with a limited narrative value, and yet, never without some kind of value.

When we look closely at Moretti, it is clear that whilst his way of literary mapping emerges from Bakhtin without explicitly stating this, it also limits what the chronotope has to offer, in part by its strong focus on the spatial at the expense of the temporal, but also in its focus on the chronotope at a macro-level (as the determinant of genre/spatial form) rather than as intrinsic to meaning at multiple levels within the text.

Figure 18 Spanish picaresque novels of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Atlas of The European Novel, 49.

Has something been lost here? Might we be able to go ‘Back to Bakhtin’ and develop a different way of mapping the text?

Abstraction and Automation: The Limits of Formalism

Another way to understand the distinction between ‘distant’ and ‘close’ reading, and the importance of challenging the dominance of the former model in relation to DH, is to go back to around 1910 and the emergence of Russian Formalism. These proto-literary theorists argued against the (then-dominant) biographical/psychological and historical models of literary analysis by shifting critical attention away from the author and onto the underlying forms and structures of language. The importance of this for the newly emerging disciplinary identity of Literary Studies is clear:

Before Formalism, literary studies revolved around other branches of knowledge, but the Formalists provided the discipline with its own center of gravity by insisting that it had a unique and particular object of enquiry.

In close relation to advances in Semiotics and Linguistics, that recognised the autonomy of language and the necessity of distinguishing between sign and referent, the formalists focussed their efforts on identifying universal underlying structures for literature. Key figures such as Viktor Shklovsky and Roman Jakobson sought to escape from authorial approaches to literary analysis and privileged instead the unique meaning of the literary utterance. This in turn led them to search for deep universal structures at work within literature and unique to it – hence their interest in ‘morphology’ (derived from Goethe) as a means of breaking the subject of enquiry down into sub-structures and their functions. The fruition of such an approach can be seen in Victor Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale (Reference Barrie and Fairhurst1928), with its focus on a universal traditional literary form for which core elements can easily be identified.

In Britain, these principles were paralleled to some degree (although with a retained adherence to psychology) with the emergence of I. A. Richards’s Practical Criticism (1928) as an attempt to give the new discipline of English Literature greater credibility. As a moral philosopher, Richards’s understanding of English Literature as a discipline was that it could only exist alongside and in relation to other disciplines. (In this he differed from Russian formalists before him, and American New Critics after him, but he still provides a vital link between the two.) Just as formalist approaches to the subject of enquiry align it to ‘positivist empiricism – the reduction of facts to sensory data’ (Steiner, Reference Steiner2016: 253), so Richards tried to justify and validate the discipline by creating ‘scientific’ ways of producing empirical data from the analysis of undergraduate readers of poetry. Richards’s principles were then taken up in America in the 1940s and embodied in literary-critical works that sought to identify primary underlying patterns and formulas in texts in ways that clearly look back to Formalism. As a consequence of the isolation of the literary work from historical or other contexts and the privileging of its more formal elements, both Practical and New Critical approaches became centred on exploring unique intrinsic meaning as held in the use of language for ‘literary’ or ‘poetic’ expression. This is what is meant by the resulting interpretative method of close reading: a mode of high-level analysis and attention to elements (such as metaphor and symbol; rhythm and metre; ambiguity and paradox) that unite form and content to produce meaning in works of literature. Crucially, however, if this was a method back in the 1930s and 1940s, it is certainly not understood to be so today. Close reading is a skill – a necessary mode of attentive analysis to details of language and meaning that occurs in conjunction with historical, theoretical, and philosophical frames (the wheel turns full circle).

Moretti’s account of distant reading and desire to develop a ‘morphology’ for literature is implicitly underpinned by early formalist attempts to respond to literature more scientifically. But – crucially – what this brief history has sought to show is that, although distant reading is defined against and in opposition to close reading, both practices find a shared origin in Formalism.

This is vitally important when we return to the question of how to digitise literature today, because it makes clear that there were always two divergent ways of applying those formalist principles: to scientific ends (capable of computation to reveal patterns or elicit data), and far more subjectively in combined understanding of language and form at multiple levels. If this was true in relation to Literary Studies in the 1920s and 1930s, it is also true of Digital Literary Studies in the 2020s. Distant reading seeks, like Formalism, to elicit core elements from across the whole, using digital tools not available to the formalists to make the scope of exploration for underlying universals far larger than they could have imagined, as well as automating it. But an alternative way of working with texts allowing for multiple scales and zooming in and out is also there – as Bakhtin himself was well aware.