Introduction

Voters in parliamentary systems face a dilemma. Not only must they choose a candidate to represent them in the legislature, but their choice of representation in the legislature also contributes to who forms the cabinet. Voters with preferences over types of cabinet then have to consider not only their expectations and preferences over district-level outcomes but also their preferences and expectations over the national-level outcome.

It has become increasingly common for politicians to try to leverage preferences over government types. For example, the 2007 Quebec provincial election resulted in the first minority government in 129 years and fractured the once stable party system: the conservative Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ) became the official opposition, winning 41 seats to the government's 48. In response to this perceived parliamentary instability, as well as the looming economic crisis, Premier Jean Charest called a snap election in 2008. Seeking a majority government, Charest argued that “we can't face an economic storm with three hands on the rudder” (CBC News, 2008). The need for a majority government was evident and pressing: parliamentary uncertainty was coupled with the economic downturn in the premier's direct appeal for a legislative majority, something that his Liberal Party ultimately received in 2008 (see Bélanger and Gélineau, Reference Bélanger and Gélineau2011; Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski, Reference Daoust and Péloquin-Skulski2021). Similarly, in the 2018 Ontario provincial election in Canada, when it became clear that the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party would win the most seats, the incumbent Liberal premier, Kathleen Wynne, urged voters to support her party in order to deny the PC Party a majority (CBC News, 2018). Preferences over government type have the potential to motivate a different type of strategic voting.

Canada is an ideal case to examine the influence of second-order preferences on vote choice. Although the Canadian political system has diverged from the two-party expectations that Duverger (Reference Duverger1954) argued would come from plurality electoral systems (Gaines, Reference Gaines1999; Johnston, Reference Johnston2017), Canadian voters remain nevertheless subject to Duverger's “psychological effect,” which induces a subset of Canadian voters to vote for their second-preferred party as a way to block a lesser-preferred party from winning constituent representation.

And while there is a growing body of literature that suggests that Canadians respond to campaign dynamics (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Nadeau, Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004; Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte1996; Kilabarda et al., Reference Kilibarda, van der Linden and Dufresne2020) and that media coverage, polling and debates can affect respondents’ vote choice, the extent to which campaign dynamics affect the type of government preference remains to be determined. Further, little is known about how preferences over type of government might interact with beliefs about the election outcome to influence individual-level vote choice. Daoust (Reference Daoust, Stephenson, Aldrich and Blais2018) provides clear evidence that voters do use these preferences in making strategic votes. Our study differs from Daoust in that we observe how government preferences vary within intended vote and, crucially, that we find a considerable strategic voting incentive among supporters of the incumbent governing party. Our analysis allows us to show that the Liberals are in the most precarious situation and that, paradoxically, those who prefer a Liberal minority in fact opt not to vote Liberal at all. This demonstrates that future studies should note that strategic voting might also reflect government preferences and the voter's ability to vote for a non-preferred party to seemingly limit the possibility of a majority government.

Minority Governments in Canada

Minority governments have become more prominent at the federal level in Canada recently. Eleven minority governments were elected from 1867 until the beginning of the twenty-first century, while five of the eight federal elections held since 2000 have resulted in minority governments, often in quick succession. Yet the presence of minority governments and voters’ reactions to these governments remains relatively understudied. Although some research has been done on minority governments from an institutional perspective (Godbout and Høyland, Reference Godbout and Høyland2011; Russell, Reference Russell2008, Reference Russell, Russell and Sossin2009; Strøm, Reference Strøm1990; Thomas, Reference Thomas2007), we know relatively little about minority governments from the voter's perspective. Dufresne and Nevitte (Reference Dufresne and Nevitte2014) are responsible for one of the most relevant studies that directly look at support for minority governments in Canada. Importantly, they find that support for minority government is positively associated with supporting a minor party and that there is also support for minority government among major-party partisans who believe their preferred party is likely to lose the upcoming election. They further find strong support for minority governments among those who are “averse to a concentration of authority” (Dufresne and Nevitte, Reference Dufresne and Nevitte2014: 837).

Because governments in a minority setting require the consent of the chamber to continue governing, proponents of minority government argue that this structure leads to a more moderate form of governing (Russell, Reference Russell2008). On the one hand, we recognize that support and opposition toward minority parliaments are heavily influenced by partisanship, electoral expectations, consociationalism, and opposition to the concentration of power (Dufresne and Nevitte, Reference Dufresne and Nevitte2014). On the other hand, we argue that government preferences can explain vote choice as well. A voter must take the likelihood of winning and the potential outcome into account when choosing to vote, as we discuss below. For this reason, preferences about government type serve as a variable that can, in part, explain vote choice. These effects are concentrated more among potential strategic voters who not only might desert their preferred party in an attempt to block a lesser-preferred party from winning the local riding but also might do so to try to block a majority government. Those who prefer a minority government, then, might vote in such a way to maximize this potential outcome.

Campaign Effects and Strategic Voting

Although political scientists in the twentieth century tended to believe that campaigns mattered little and instead focused on the “fundamental models” of elections, the importance of campaigns has been recognized in recent decades. In the Canadian context, Johnston and colleagues (Reference Johnston, Blais and Crête1992, 1996) have demonstrated how the 1988 campaign and the Charlottetown referendum campaign influenced voters. Fournier et al. (Reference Fournier, Nadeau, Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004) find that Canadians are responsive to campaign dynamics, the debate and media coverage and that many voters make up their mind during the campaign. A recent example of this phenomenon was the “orange wave” in Quebec, where Jack Layton's appearance on the popular Quebec talk show Tout le monde en parle, as well as the publication of numerous polls that demonstrated that the New Democratic Party (NDP) was for the first time in the party's history a viable party in the province, resulted in a pronounced increase in NDP vote intent in Quebec (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Cutler, Soroka, Stolle and Bélanger2013; Kilabarda et al., Reference Kilibarda, van der Linden and Dufresne2020).

The influences of the campaign—often seen at the macro level, in the form of debates, leaders’ traits, or media coverage—can also occur at the micro level. Party preferences and the expectations of the results at the local level have been found to affect strategic voting (Merolla and Stephenson, Reference Merolla and Stephenson2007; Blais, Reference Blais2002; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Nadeau, Gidengil and Nevitte2001, Reference Blais, Dostie-Goulet, Bodet, Grofman, Bodet and Bowler2009; Blais and Nadeau, Reference Blais and Nadeau1996) and turnout (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Rivard and Hodgson2022). Strategic voting is associated with a preference for a minority government (Daoust, Reference Daoust, Stephenson, Aldrich and Blais2018), more common as polarization increases (Daoust and Bol, Reference Daoust and Bol2020), and the likelihood of deserting one's preferred party decreases as voters are surveyed closer to election day (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Loewen, Rubenson, Stephenson, Gidengil, Stephenson, Aldrich and Blais2018). Loewen et al. (Reference Loewen, Hinton and Sheffer2015) find that those that can reason strategically rely more on probabilistic information when deciding to vote strategically.

This research note serves to add to the literature identified above. In particular, we are most interested with the extent to which voters respond to the type of preferred government.

Case Selection

The 2019 Canadian election provides a useful context in which to study this question. It followed the end of the majority government of the Liberal Party of Canada (LPC), initially elected in 2015. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau remained leader of the LPC and contested the election against three new party leaders: Jagmeet Singh of the NDP, Andrew Scheer of the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) and Yves-François Blanchet of the Bloc Québécois (BQ).

Campaign-period polling data indicated that vote intention between the LPC and CPC was quite close throughout the writ period, with the NDP seeing a late surge in support closer to election day. Indeed, four polls published on the penultimate day pointed to a toss-up: both EKOS and Research Co. gave the Liberals an advantage over the CPC by 4 per cent and 1 per cent, respectively, whereas Mainstreet and Nanos had the CPC up by less than 1 per cent. No poll had either the Liberals or Conservatives around the 38 per cent mark generally required to win a majority government. In this toss-up election, then, a minority government seemed very likely. In this respect, the 2019 election can serve as an ideal case to determine whether a preference for a minority government has an effect on vote choice, given a situation in which the national results acted as a horse race.

In addition to analyzing the 2019 election, we replicate our main results using data from 2011, which is shown in the online appendix. While the context of that election was slightly different, we include the results to show that the key findings we observe are not limited to 2019.

This leads us to our main question: Does preference for government type affect vote choice? That is, when the information that the polls offer to voters is that the election is close and that a minority government is likely, are voters conditioned more by national or local expectations? We also look at how the dynamics of the Bloc affect voters.

Data

To address these questions and to observe the impact of preferences and expectation on vote choice, we rely on data from the 2019 Canadian Election Study (CES).

The 2019 CES is unique in its large rolling cross section that covers the entire campaign period of the 2019 election; an average of 990 respondents were interviewed every day beginning September 13 and ending October 20. This information allows us to track campaign dynamics over time and to assess their influence on voter preferences. The sample size is over 37,000 respondents interviewed online during the 2019 election campaign. Our total campaign- period sample is 58 per cent women, the mean age is 49 (with a standard deviation of 16.6), and 22 per cent of the sample is from Quebec.

Our main outcome variable is intended vote choice. Because our focus is on the four largest Canadian parties, we limit analysis to the LPC, CPC, NDP and BQ. We code these as binary choices to explain what leads voters to choose specific parties, focusing on when a voter would choose each party in turn. Models involving the BQ are presented in Quebec only.

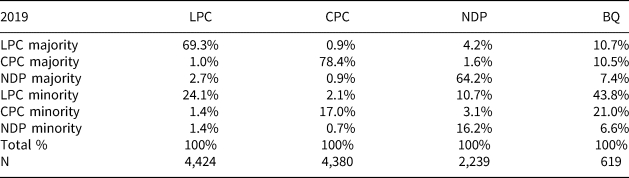

To measure government preference, we include the measure summarized in Table 1. This measure asks respondents to pick their preferred type of government among six options, choosing between minority or majority governments for each of the largest three national parties, reflecting the notion that only the LPC and CPC and maybe the NDP had prospects of forming government. Simply put, respondents were asked if they preferred a Liberal majority or minority, a Conservative majority or minority, or an NDP majority or minority. Respondents could only select one preferred outcome. The advantage of this question is that it captures the preferences of third-party and swing voters more accurately; a voter might be unsure whether to vote for the NDP or the LPC but hold a fixed preference for a LPC minority government. Similarly, a BQ voter might be confident in their BQ vote choice but also want a CPC minority government in power. Indeed, because the BQ runs so few candidates, it cannot form government.

Table 1 Vote by Government Preference in 2019 (columns may not add up to 100% due to rounding)

One concern might be that local preferences and viability outweigh national considerations. If a significant number of voters focus on the local race instead of national factors, our findings might be biased. Recent research suggests this is unlikely; there is substantial agreement that local candidate evaluations are decisive for less than 10 per cent of voters (Blais et al, Reference Blais, Gidengil, Dobrzynska, Nevitte and Nadeau2003; Blais and Daoust, Reference Blais and Daoust2017; Sevi et al. Reference Sevi, Aviña and Blais2022). We also control for the party that the respondent thought would win in their riding, to control for candidate viability (with Conservatives serving as the reference category).

In addition, following Cutler et al. (Reference Cutler, Rivard and Hodgson2022), we include the relative chance of the respondent's preferred party measured as the subjective chance they give their preferred candidate compared to the subjective chance they give the next highest candidate. This measure ranges from 100 to −100. If a voter is sure their own candidate will win, then the difference between this candidate and their opponent will be 100; if a voter is sure their candidate will lose and a different candidate will win, the difference is thus −100. An even race would produce a score of 0. In simple terms, values closer to 100 indicate a higher subjective belief that their preferred candidate will win and vice versa. However, it is still possible that the impact of strategic reasoning depends on the viability of the different candidates at the local level; if strategic reasoning is more or less prominent depending on the viability of different candidates, our estimates will be biased. We must therefore assume that when controlling for viability, strategic voting is constant.

We also control for the partisan preference of voters. In our main models, we use the preferred party of voters measured by the combination of party and party leader that voters most prefer. This is based on feeling thermometer scores that respondents give; their preferred party is the one they feel warmest toward. In the online appendix, we replicate this using only feeling thermometer scores for the party and for the leader (in different models); the results are similar across models.

Finally, we include a number of control variables that we omit from all tables for clarity: fixed effects for the respondent's home province, age, gender, a dummy variable for Catholics, party identification, income, and education.

To model the relationship between preference about government type and reported vote choice, and because of Canada's multiparty system, we employ a series of ordinary least square (OLS) regressions. The dependent variables in each model are dummy variables that compare the identified vote intention with all other parties. As such, each column is a linear probability model where the identified party takes the form of 1 and all other vote intentions take the form of zero. We present all models twice, once for Canada outside Quebec and once for Quebec exclusively. We further present multinomial regression results in the online appendix; the results are largely consistent with OLS.

Findings

We begin by presenting descriptive information on our main variable of interest: preference about government type. Table 1 is a crosstab of vote intent by preferred government outcome. Because the CES only asked the preferred outcome question to a subset of the sample, the sample sizes for this analysis are significantly smaller than the overall samples of the election studies.

In 2019, 93 per cent of Liberal voters, 95 per cent of Conservative voters, and 80 per cent of NDP voters desired that their party form government. The 95 per cent retention rate by the Liberals was significantly higher than their 80 per cent retention rate in 2011. This is not altogether surprising given that the Liberals had been languishing in public opinion polls under the leadership of Michael Ignatieff in 2011 and were the incumbent government in 2019. Yet the Liberals were in a precarious situation in 2019: nearly a quarter of Liberal voters preferred a Liberal minority government—the highest share of same-party government preferences across the three major parties. This, we argue, might structure partisan considerations among Liberal voters. Liberal voters with a minority preference might be inclined to desert the Liberals for a different party in an attempt to secure this minority outcome, trying to block majority government for the party.

Second, there are a minority of voters that intend to vote for one of the three major parties but have a government preference that diverges from their intended vote. These preferences are smallest within the two major parties: only 4 per cent of Liberal voters favour an NDP government and only 3 per cent of Conservative voters favour a Liberal government. In contrast, nearly 15 per cent of NDP voters preferred a Liberal government (with a preference for a minority) and over half of the Bloc voters preferred a Liberal government. Bloc voters are an interesting case. The Bloc only runs candidates in Quebec and refuses to be a coalition partner. The preference for a Liberal government in relation to the Conservatives among Bloc voters reflects the vestiges of the twentieth-century Canadian party system where the Quebec pole was successfully integrated by the Liberals (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017). Bloc voters, then, face a choice at the ballot box: to include Quebec in the national government or to vote for a regionally concentrated political party that seeks to extract province-specific demands from the government. In a minority setting, such as what followed the 2019 election, a successful, regionally concentrated political party might be able to influence public policy. From this perspective, Bloc voters might be more willing to vote for the Bloc when expecting a minority government.

Table 2 presents linear probability models for the likelihood of voting for the Liberals, Conservatives and NDP. Each column is a linear probability model where the identified party takes the form of 1 and all other vote intentions take the form zero. The coefficients thus represent the impact of each variable on the probability of voting for the specific party compared to all other parties. We are most interested in the effects of government preferences on vote choice and thus exclude other control variables from the tables. In both tables, Liberal majority preferences serve as the reference category; the coefficients compare each other type of preference to this.

Table 2 Relationship between Expectations, Preference about Government Type, and Vote Choice outside Quebec in 2019 (control variables are omitted from the table)

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01

The first column of Table 2 demonstrates a consistency in Liberal voting intention. Unsurprisingly, Conservative government preferences are negatively associated with a likelihood of voting Liberal. Yet preference for a Liberal minority government is likewise negatively associated with voting for the Liberals such that those who preferred a Liberal minority were almost 8 percentage points less likely to vote for the Liberals than those who wanted a majority government.

Importantly, this controls for the respondent's preferred party and the relative chances of their preferred party. Regardless of the respondent's preferences over party and their views of what local candidate is likely to win, their preference about government type causes Liberal voters to be less likely to vote for the party if they want a majority. In addition to looking at preferred parties, we include three additional measures for partisan preference in the online appendix; across all models, the results are substantively and significantly the same.

The size of the difference between Liberal majority and Liberal minority voters is unique to the Liberal Party; for the Conservative Party, the difference is only 1.5 percentage points, and for the New Democrats, the difference is 2.7 percentage points. That the Liberals have a poor retention among those who prefer a Liberal minority government is problematic for the party for two reasons. First, those who preferred a Conservative minority were 52 percentage points more likely to vote for the CPC. Those who preferred an NDP minority were 47 percentage points more likely to vote for the NDP in 2019. The negative coefficients in the first columns of Tables 2 and 3 demonstrate that party defection is largely concentrated among those who prefer a Liberal minority government, indicating that voters might opt to not vote the Liberals as a way in which to block a potential majority government. Paradoxically, not voting for the Liberals might be the best way to ensure that one's preferred Liberal minority government is reached.

Table 3 Relationship between Expectations, Preference about Government Type, and Vote Choice in Quebec in 2019 (control variables are omitted from the table)

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01

Table 3 replicates the models from Table 2 but in Quebec instead of the rest of Canada. Focusing solely on the Quebec electorate demonstrates the extent to which behaviours varied between Quebec and the rest of Canada.

As in the rest of Canada, the LPC minority coefficient is negative. But unlike the rest of Canada, the coefficient is over twice as large in 2019: outside Quebec, Liberal minority voters were 7.7 percentage points less likely to vote for the Liberal Party, while in Quebec, they are almost 17 percentage points more likely to defect. This is particularly interesting given that the Liberals were both the incumbent governing party and led by a Quebecker—a Quebec-born leader generally rewards the party in the province (Johnston, Reference Johnston2019).

In Quebec, we also see that the size of the Liberal defection problem is not unique; both the CPC and NDP also face significant defections among their minority voters. For the CPC in Quebec, voters who prefer a minority to a majority are 15 percentage points less likely to vote for the CPC. For the NDP, this difference is about 10 percentage points. Interestingly, the BQ mainly benefits from these defections, as their support is predicted primarily by preferences for minority government and not by preferences for majorities.

This is likely because the Bloc only runs candidates in Quebec and thus cannot form government. Preferring an LPC or CPC minority to a majority and voting for the Bloc, we argue, is not incongruous. Instead, it reflects the realities of post-1993 Canadian politics. The Bloc acts as a party of regional defence, offering voters a province-specific voice in the national legislature. Particularly given that Quebec was a necessary and sufficient condition for a Liberal majority in the twentieth century, voting for the Bloc serves to prevent the Liberals from winning a majority government (see Johnston, Reference Johnston2017, Table 3.1).

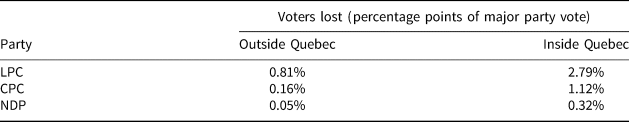

These effect sizes can be quantified specifically, if we make the strong assumption that the coefficients we estimate are exactly right and that our sample is representative. For each party, we can then estimate how many voters preferred a minority government of that party and use the estimated effect of preferring a minority (compared to a majority of the same party) to estimate how much larger their popular vote would be had those voters preferred a majority government. For instance, if 10 per cent of voters wanted a minority Liberal government, we could say that had those voters all wanted a majority, then 10 per cent of voters would be 8 per cent more likely to vote LPC had they wanted a majority government, increasing the LPC's vote share by 0.8 per cent.

We summarize these results in Table 4, looking at the percentage point loss of the major- party vote share each party faced. We find that outside Quebec, none of the parties lost a significant number of voters, with the Liberals losing the most at 0.8 per cent. Inside Quebec, however, the impact is much larger, as both the LPC and CPC lost over 1 per cent in support, generally to the Bloc. In total, this suggests that for about 1 per cent of voters outside Quebec and 4 per cent of voters inside Quebec, preference about government type is pivotal in causing them to abandon their preferred party (for a much larger fraction of Canadians, preference about government type is pivotal in causing them to remain with their preferred party). Between 2 per cent and 8 per cent of voters are motivated by local candidate characteristics that receive significant attention (Sevi et al., Reference Sevi, Aviña and Blais2022), so these effect sizes are certainly worthy of attention.

Table 4 Summary of Popular Vote Loss by Party inside and outside Quebec

Discussion and Conclusion

Voters in multiparty systems face two related dilemmas. First, they face a strategic decision at the local level: they must decide among multiple parties that are likely to be competitive and among those that they prefer. Second, they face a further dilemma of selecting a candidate likely to result in the type of government or coalition they want. A voter must consider both the local and national impacts of their vote choice. Voters in Canada face exactly this dilemma; because Canada operates using a Westminster parliamentary structure, voters must anticipate electoral results to achieve the government they want. This makes Canada an ideal place to study strategic behaviour in multiparty elections.

Using data from the 2019 federal election, we show that preferences over government type are important. Vote choice is jointly determined by preference over government results and beliefs about local viability. In a system in which only two of the major parties are likely to form government despite multiple parties being competitive at the local level, we see that preferences over the outcome are strongly related to vote choice, that national and local expectations matter little, and that the Quebec electorate exists in a political reality different from that of the rest of Canada.

Empirically, we show that outside Quebec, the Liberals face the largest challenge holding on to voters who prefer a minority to a majority. Among voters who prefer other parties, they are substantively about as likely to vote for their preferred party regardless of whether they prefer a minority or majority. In Quebec, the role of minority preferences is exaggerated, as the Bloc provides a natural home for voters wishing to prevent a majority government; across all three major national parties, preferring a minority is negatively associated with vote choice in Quebec.

Liberals outside Quebec might face defection at higher rates because their voters feel as if they have choices that can force a Liberal minority, while those who support the NDP and CPC might not feel they have this choice. A voter who wants a Liberal minority could reasonably have defected to the NDP or Green Party or even the CPC without being concerned they might drive the other party into a winning position federally, while a NDP or CPC voter could not reasonably expect the same if they voted for the centrist Liberal Party. Thus the Liberals’ median position, which has traditionally benefited them, might also be the cause for defections in 2019.

We point to this as an important aspect of voter preferences for parties to consider. The future viability of third parties in Canadian politics largely depends on their continued ability to earn votes from voters who prefer minority to majority governments. Our evidence suggests these voters, especially if they prefer the Liberal Party, are likely the most persuadable type of voters in Canada right now, but if the share of minority voters drop, the NDP and Bloc will struggle to maintain their positions as viable alternatives at the local level.

Beyond the practical considerations, we contribute to the existing literature on strategic voting by adding a second layer to the potential strategy voters could employ. While there is an extensive literature on voting strategically at the constituency level, little is known about how national considerations affect strategy. While national preferences matter, voters are only marginally attuned to incentives that change with the state of the national campaign.

Our results also indicate that future studies of strategic voting and vote choice would do well do address the extent to which partisan balancing occurs. Balancing is a process in which voters intentionally vote for a party that differs from their ideological preference as a way to achieve more moderate policy outcomes or to pull policy away from the median position (Kedar, Reference Kedar2009). That those who prefer a Liberal minority are less likely to vote for the Liberals might indicate two things. First, as discussed, it could indicate that voters might be paradoxically trying to ensure a Liberal government by not voting for the party.

Second, in Canada, minority governments might give third parties more influence, given that they require parliamentary co-operation for their survival (Russell, Reference Russell2008). Not voting for the Liberals and instead voting for the NDP might represent an opportunity for voters to attempt to pull government policy toward the left, assuming the Liberal Party co-operates with the NDP in the legislature. This pattern would tangentially follow ones similar to what is observed in Israel, where the psychological mechanisms of the Duvergerian expectations can influence voters in proportional systems, with voters voting strategically on the expected government coalition and the formateur (Bargsted and Kedar, Reference Bargsted and Kedar2009; see also Duch et al., Reference Duch, May and Armstrong II2010; Gschwend et al., Reference Gschwend, Johnston and Pattie2003; Gschwend, Reference Gschwend2007). These expectations might be at play in multiparty and majoritarian cases, as in Canada, where voters cast strategic ballots to extract policy demands from the governing party. As such, these “strategic considerations” differ from the traditionally understood logic of strategic voting: voters might not be voting for their non-preferred party to block a lesser preferred party but instead to elect a government that needs legislative support to provide public policy.

Our results also speak to two specific Canadian election dynamics that are often studied. We show that Liberal voters, at a given level of support for the Liberal Party, are not all the same. Those who prefer minority governments act significantly differently than those who prefer majorities. Second, dynamics in Quebec are substantially and significantly different than those outside Quebec. The presence of an additional regional party has an important impact on voter behaviour in the province and allows voters across the spectrum to defect from their preferred party if they want to avoid majority governments.

Future research should examine these preferences more carefully. In countries with local elections that contribute to a national-level outcome, voters must balance preferences over local outcomes with preferences over national outcomes. Examples such as the local popularity of the Green Party in German national elections despite the party's weak performance on the party vote suggest that voters can have distinct preferences across levels of amalgamation and must make decisions to balance them.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fred Cutler, Jean-François Godbout, Marc André Bodet and David Fortunato for their helpful comments and feedback.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S000842392200052X