The oldest Greek curse tablets date to the late sixth and early fifth centuries bce, and hail from the Sicilian cities of Selinous and Himera. These objects provide a rich dataset of which historical questions can be asked – especially concerning the origins, development, and function of these ritual texts, and their connection to older, oral traditions. This article assesses the relationship between the oldest Sicilian curse tablets and oral curse traditions, as much early Greek writing is thought to have recorded and replicated the spoken word; many early written texts thus had oral antecedents. This orality paradigm is understood to apply to early Greek curse tablets:

Curses, whether private or public, must date back long before writing was used for them, and the efficacy of the curse did not depend on its being written. They were usually spoken, like the horrific imprecations of Oedipus. In a sense, then, this was another case where writing was grafted on to an earlier (and continuing) oral feature.Footnote 1

Yet a close study of the oldest Greek curse tablets reveals that few, in fact, preserve signs of orality or speech. There are no verbs of speaking, incanting, cursing, singing, binding; no deictic language; no metre. This destabilizes the notion that written curses evolved from earlier oral curses and incantations. Instead, curse tablets from late archaic Sicily emerge with a written self-awareness of sorts, suggesting the influence of written and material, rather than oral, precursors. These professedly textual objects employ verbs of writing to curse their victims, forms of γράφω (‘I write’) and its compounds (ἐνγράφω, ‘I inscribe’; καταγράφω, ‘I write down’; ἀπογράφω, ‘I enrol’). They also exhibit textual distortion, scribal symbols, abbreviations, and columnar lists of names, all of which ground them in the realm of writing. Many of the oldest curse tablets were judicial in nature, concerned with trials in the law courts of Selinous, and may themselves have developed alongside or in response to the spread of legal writing in the sixth-century polis. In other words, it may have been the new role of writing in the litigation process that led to the emergence of curse tablets in western Sicily by the late sixth century bce.

Background

Let us first situate the oldest curse tablets, which date to the late sixth century bce and come exclusively from the Greek west, with respect to earlier developments in Greek writing. Historians now date the adoption of the Greek alphabet to the ninth century bce, with written literacy spreading across the Greek world soon thereafter.Footnote 2 By the eighth century, Greek scripts were used to mark property and claim ownership; similarly, the nascent alphabet was employed for commercial purposes, for labelling objects used in trade and exchange. Early Greek writing was also exploited for elite display and consumption. Thus, by inscribing ‘I am the cup of Nestor, good to drink with’ upon a wine cup, a cheeky Euboian in Pithekoussai was indulging a new cultural fashion, illuminating the process by which the pre-existing alphabetic script made its way into the aristocratic symposium (an archaeologically visible phenomenon, relying as it did upon non-perishable ceramic media).Footnote 3 Divine dedications were labelled by the end of the eighth century bce and, by the first half of the seventh, grave stelai (grave markers) had joined the ranks of objects marked by the nascent technology of writing. New epigraphic discoveries continue to complicate the overview given above, and will further expand our chronological, geographic, and historical understandings of early Greek writing. And of course the picture would be enhanced, though perhaps not changed entirely, if we still had access to the perishable materials upon which early Greek texts were written; most inscriptions on wood, wax, leather, and other organic materials such as papyrus are irrecoverably lost, but also carried great quantities of text.

Scholars have long questioned the relationship of early Greek writing to orality, and the communis opinio holds that writing in early Greece served as the handmaiden of speech, drawing meaning and function from older oral phenomena: ‘most archaic writing was largely used in the service of the spoken word…the written word continues in other spheres throughout the ancient world largely to reproduce the spoken word’;Footnote 4 ‘Early writing appears to have been used in service of the spoken word: most of the early texts are statements meant to be read aloud.’Footnote 5 Examples include both grave stelai and boundary stones (horoi), which existed long before the Greek alphabet. Writing was later grafted onto these markers in the form of inscriptions – added mementos with new representative power – but nothing that singly carried the weight of communication, or led the physical markers themselves to lose significance.Footnote 6 Inscribed on stone, many funerary epigrams captured sentiments meant to be spoken aloud: hence these written texts did communicate something oral. Here writing served to preserve and amplify older oral customs, which helps to explain why many Archaic grave stelai were composed in verse. Returning, then, to the question of whether early Greek writing simply reinforced and fortified extant oral traditions, one answer would be yes, sometimes it did. In other instances, however, this framework is not applicable. Early Greek graffiti on amphorae from Pithecusai describe types and commodities of trade goods, for example, suggesting the important role of the new Greek alphabet in commerce; there are no traces of orality in these early inscriptions.Footnote 7

Within this broader conversation, we might consider the evidence presented by a rapidly growing body of late archaic Greek inscriptions: curse tablets. The earliest curse tablets mark a later development in archaic writing, appearing a century or so after the oldest inscribed civic laws, and more than two centuries after the earliest Greek sympotic inscriptions on ceramic. Beginning in western Sicily shortly before 500 bce, these ritual texts circulated within a (still) predominantly oral society, but one in which writing was becoming more prominent. Their emergence and rapid proliferation provides a valuable dataset for addressing questions of orality and written text in the sixth-century Mediterranean. What relationship do these ritual texts bear to orality? Were these objects first used in the service of the spoken word, and did they draw meaning from older oral habits – freezing speech in textual form, as scholars have suggested – or did they take distance from oral traditions?

A close study of the oldest curse tablets suggests that the majority do not record statements that were meant to be spoken; here writing was neither the servant of speech nor a mode of communicating what would otherwise have been uttered aloud. Rather than operating in the shadow of the spoken word, at least entirely or primarily so, late sixth-century curse tablets exhibit self-awareness of their written nature. The first tablets bear few traces of orality, and probably did not record older, oral curses – or at least this is not what the extant evidence suggests.

Curse tablets emerged at a time when written text had begun to diversify. These were years in which written literacy was rapidly spreading and, prior to 500 bce in the Sicilian poleis, epichoric scripts were well established. Svenbro has suggested that from 550 to 540 bce, ‘non-egocentric’ inscriptions begin to emerge.Footnote 8 These texts no longer ‘speak’ in the same first-person voice as the Cup of Nestor above, with forms of εἰμί (‘I am’) or otherwise. Thus, in contrast to an inscription like IG I2 410, which states ‘To all men who ask, I answer alike, that Andron son of Antiphanes dedicated me here as a tithe’, Svenbro shows how, by the mid-sixth century, we start to find texts that read ‘This is so-and-so's tomb’ or ‘So-and-so lies here’.Footnote 9 By the later sixth century, writing had come to be used more impersonally, as a ‘third-person notice of information’.Footnote 10 Greek curse tablets emerge at this stage in the development of written literacy, a period in which writing was becoming more autonomous.

Selinous and the oldest Greek curse tablets

Current evidence suggests that Greek curse tablets had their beginnings in western Sicily during the late sixth century bce, in the city of Selinous and possibly also Himera.Footnote 11 Roughly seventy curse tablets have been published from Sicily, and more than half of these emerged from Selinous and date to the late sixth and fifth centuries bce. The discovery of fifty-four new curse tablets in Himera's Western Necropolis will, once published, bring the total count of Sicilian curse tablets to around 125 – a sizeable corpus indeed; as only two curse tablets from Himera have currently been published, however, this study primarily draws upon tablets known from Selinous.Footnote 12 By 2009, the Selinountine curse-count had reached forty-five lead tablets, and these include the earliest curses, from around or just before 500 bce.Footnote 13 This datum is and shall remain significant, even as future discoveries expand the discussion and considerably increase the total number of Sicilian curse tablets.

The chronologies of early Selinountine curses are based on the style of writing, patterns in dialect (such as the appearance of Ionicisms after the mid-fifth century), and letter forms – imprecise but useful dating criteria, especially as precise archaeological contexts are unknown. The dates provided below should therefore be understood as approximate but representative of scholarly consensus.Footnote 14 In general I follow the dating rubric of Bettarini's Corpus delle defixiones di Selinunte (henceforth CDS); Bettarini autopsied the Selinountine materials most recently, and drew upon onomastic, prosopographic, and dialectic comparanda in composing the corpus.Footnote 15 Dates assigned in other editions are taken into account and, when different from Bettarini's assessment, the consensus date is given.Footnote 16 Dates assigned to early Selinountine tablets from well before 500 bce, for example ‘550 bce’ or ‘first half of the sixth century bce’, are generally considered too early by scholarly consensus.Footnote 17 That said, we cannot assume that we have found the absolute earliest curse tablet(s), or that the practice arose ex nihilo in the year 500 bce – especially as some of the earliest Selinountine curse tablets exhibit remarkably developed texts and were deposited in two discrete extramural sites by this time. Ritualized cursing was surely gestating and developing in Selinous during the final decades of the sixth century, and possibly around this time or shortly thereafter in Himera to the north.

The oldest known curse tablets appear in two separate, but contemporary, Selinountine contexts by 500 bce – one funerary (the Buffa necropolis), the other sacred (the Gaggera precincts). The oldest curse tablets from Kamarina and Gela, which date to the mid-fifth century bce, emerge in funerary contexts; the new tablets from Himera were found in graves, the oldest of which has been dated to the second decade of the fifth century bce.Footnote 18 Early curse tablets appear to cluster in the Greek poleis of western Sicily, and share a mortuary component: they were deposited in cemeteries and graves – primarily but not exclusively, as we shall see – during the final stage in the ritual process. At least five curse tablets from around 500 bce emerged from the Buffa necropolis (CDS 15–19), with an additional tablet from c. 450 bce recovered from Selinous’ Manuzza necropolis (discussed below). In no instance do we know precisely where within these two cemeteries the tablets derived: whether in or outside graves, inside funerary vessels or on the person of the corpse, what sorts of tombs were preferred for deposition, and so forth. We can only speak to their broad mortuary context, and to the texts incised on these ritual objects. (In contrast, the new finds from Himera provide fine-grained detail relating to depositional context.)

At the same time in which tablets were buried in Selinous’ Buffa necropolis, curse practice appeared at another extramural site in the city: the precinct of Malophoros, and perhaps also the contiguous sanctuary of Meilichios on Selinous’ western Gaggera hill. No fewer than thirteen Greek curse tablets are known to have come from the Gaggera precincts (CDS 1, 20–31).Footnote 19 Demeter Malophoros, Persephone, and also Hekate, who received cult in a precinct contiguous to that of Malophoros, were all associated with the Underworld. The Underworld connection was surely the fil rouge tying the Gaggera precincts to the Buffa necropolis as apt sites for curse-casting; both localities afforded contact with subterranean, chthonic powers.

A survey of the earliest curse tablets from the Buffa necropolis reveals a number of themes: demands for the ἀτέλεια or ‘unfulfilment’ of the ‘deeds and words’ of victims; the targeting of victims’ tongues; lists of names; and the use of ‘writing’ verbs (γράφω and compounds) to curse the victim. Additional motifs emerge in the Gaggera tablets, notably the ‘twisting’ or ‘turning back’ of the victim's tongue; the distortion of text; invocation of goddesses; and destruction clauses drawn from public curses (arai). The presence of several of these themes in the earliest tablets suggests that an economy of curse language and practice was established by 500 bce in Selinous. Some tablets do preserve spoken formulae, recording expressions that likely did circulate orally before their incision on lead. For example, one Sicilian curse employs the phrase εἶεν ἐξόλειαι καὶ αὐτο͂ν καὶ γενεᾶς, ‘let there be utter destruction both of these men and of their kin!’ (CDS 24), a construction drawn from sacred and civic curses (arai) found in the public realm.Footnote 20 Yet many others – the majority, and the earliest – emerge from the outset as self-consciously textual, sometimes assertively so.

It is important to note that early tablets from Selinous contain only prose; the same can be said for the two published curses from Himera. Unlike some of the earliest Greek inscriptions, which unfolded in metre (the Cup of Nestor, the Dipylon Oinochoe), late archaic Sicilian curses are decidedly not metrical. We find other ritual texts composed in hexameters in western Sicily, so this genre of metrical incantation was not unfamiliar there; the choice by early curse-writers to not use metre was a deliberate one.Footnote 21 Nor do the oldest curse texts employ verbs of speaking, incanting, singing, or binding. Finally, deictic language is largely absent. Let us now turn to these texts, which might be studied in four thematic groups: those that employ ‘writing’ verbs, that is, forms of γράφω and compounds (ἐνγράφω, καταγράφω, ἀπογράφω); those that exhibit textual distortion; those with scribal symbols or abbreviations; and columnar lists of names.

Verbs of writing: γράφω and compounds

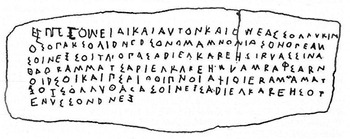

A striking number of late archaic curses from Selinous employ γράφω as the primary, operative curse verb. The act of writing was thus understood as the agentive act that brought about the curse, with the verb announcing the written self-consciousness – not the orality – of the ritual act. Compounds of γράφω are also employed, including καταγράφω (‘I write down’), ἐνγράφω (‘I inscribe’), and ἀπογράφω (‘I register’). Consider the following discoid lead tablet, which dates from shortly before 500 bce. The text targets three individuals: Selinontios, Timasos, and Tyranna; it also targets their tongues. Here the ‘tongue’ (γλο͂σα) was shorthand for the opponent's speech or testimony in court – something that brought the curse-commissioner much anxiety.

CDS 20 (= SEG 4.37–8)

Selinous, Region of the Malophoros PrecinctFootnote 22

500 bce

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42568

Side A: I inscribe (ἐνγράφο̄) Selinontios and the tongue of Selinontios, twisted back for the purpose of unfulfilment, and I inscribe (ἐνγράφο̄) the tongues of the foreign co-advocates (συνδίϙο̄ν), twisted back for the purpose of unfulfilment!

Side B: I inscribe (ἐνγράφο̄) Timasos and the tongue of Timasos, twisted back for the purpose of unfulfilment, and I inscribe (ἐνγράφο̄) Tyranna and the tongue of Tyranna, twisted back for the purpose of unfulfilment – of all of them!

Much is of interest in this early curse, but for now we shall concentrate on the verbs. The text ‘inscribes’ (ἐνγράφο̄) three individuals, their tongues, and the tongues of their supporters or advocates at trial. The verb ἐνγράφο̄ is deployed four times. The curse is thus articulated and effected through an act of writing, not of speaking, cursing, incanting, or binding. A handful of other early curses from Selinous also employ compounds of the verb γράφω. Such ‘writing’ verbs are in fact the first to appear in Greek curse tablets, and constitute the majority of verbs used prior to the mid-fifth century bce. These first-person verbs emphasize the written act as the gesture that brings the curse to pass. A second curse from the Malophoros sanctuary also uses the verb ἐνγράφο̄ (CDS 21), while three others use the verb καταγράφο̄ (‘I write down’) (CDS 23, CDS 31, CDS 13).

Figure 1. CDS 20 verso, Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42568. Drawing from Gabrici (n. 15), fig. 180b; photo from V. A. Arangio Ruiz and A. Olivieri, Inscriptiones Graecae Siciliae et infimae Italiae ad ius pertinentes (Milan, 1925), 161.

Consider CDS 23 (= SEG 16.573), a rectangular lead tablet broken into two pieces, which carries a successive list of some twenty names. The first sixteen lines of text are broken into eight sections, each of which is introduced with καταγράφο̄ πὰρ τὰν ℎαγνὰν θεόν (‘I register before the Holy Goddess’):

I register Apelos, son of Lykinos, before the Holy Goddess, along with his soul and might…Plakitas the son of Nannelaios and Halos the son of Pukeleios, I register their soul and their power to the Holy Goddess! Kadosis the son of Matulaios, and Ekotis the son of Magon, I register their soul to the Holy Goddess. And this son of Phoinix the son of Kailios, I register before the Holy Goddess…

This curse again deploys compounds of the verb γράφω. Here καταγράφο̄ (‘I write down’ or ‘I register’) is employed three times, and ἐνκαταγράφο̄ (‘I enrol’) is used once (line 14). The act of writing-down the curse is emphasized. That targets are registered ‘before/to/in the presence of’ (πάρ) a divine witness with (ἐν)καταγράφο̄ probably points to the influence of written legal procedure upon this curse.

Beyond Selinous, a mid-fifth century curse from the Gela region also uses forms of ἀπογράφο̄ and γράφο̄ to target rival choregoi (SEG 57.905), while another mid-fifth century curse from Kamarina's Passo Marinaro necropolis (SEG 4.30) opens with the words ‘these men have been registered for misfortune’ ([ℎοί]δε γεγράβαται | ἐπὶ δυσπραγί̣[αι]).Footnote 23 Again, the texts suggest that the ritual efficacy of these curses lay in the act of writing; it is difficult to imagine oral antecedents for these curses, so explicitly do they assert their written character. It seems that they evolved within a written milieu of ritual curse practice which, by the early fifth century bce at Selinous, involved inscribing a piece of lead with text (often) amid the fraught preparations for a trial, and then depositing the object in a grave or sanctuary. The orality paradigm is problematic here, as the earliest texts use γράφω to curse their targets; this undermines the notion that the earliest written curses recorded older oral ones. I suspect that the prominence in early curses of γράφω and compounds (ἐνγράφω, καταγράφω, ἀπογράφω) reflects the growing use of writing in Sicily's sixth-century law courts; written judicial procedures may in turn have catalysed the earliest curse texts, which were, after all, first used for litigation as best we can tell, and drew language from the legal process (for example, registering individuals ‘before/in the presence of the Holy Goddess’). The earliest curse tablets likely developed under the umbrella of written legal procedure, and may even have been understood as ritual extensions of law court practice. Unlike some later Attic curse tablets, it seems to me that this early ‘γράφω group’ did not evolve from older, oral curse traditions – they are explicitly and self-assuredly aware of their written nature.

Textual distortion

Another way in which early Greek curses appear self-consciously written, rather than oral, is in their use of textual distortion. These inscribed curses play with the materiality and form of the written text – scrambling and twisting letters, reversing syllables in personal names, and so on – in a sympathetic or analogical sense meant to affect the victim himself. This distortion of text could only have meaning within the written realm of cursing; the metaphorical play with script had no basis in older, oral curse traditions, but depended entirely on the new technology of writing for efficacy. Consider the following tablet from Selinous’ Gaggera precincts, which contains a list of continuous names, most of which were written retrograde (the characters, however, face toward the right).

CDS 25 (= SEG 16.572)

Selinous, Region of the Malophoros PrecinctFootnote 24

475–450 bceFootnote 25

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42562

-

Philoleos, Xim<a>ros, Deias, Pythodoros, Gorgias, Pithon ←

-

Selinoi, AkroikoiFootnote 26 ←

What is striking about CDS 25 is not the continuous list of names but the deliberate distortion of letters therein. Not only were individual names incised backwards, from right to left, but some syllables within the names were scrambled or inverted.Footnote 27 The scribe incised ΝΟΘΠΙ for ΠΙΘΟΝ (Πίθον), ΣΑΓΙΡΟΓ for ΓΟΡΓΙΑΣ (Γοργίας), and ΙΟΚΟΙΡΚΑ for ΑΚΡΟΙΚΟΙ (Ἀκρ̣οικόι?), reversing the proper succession of letters. Here is an early form of analogical ‘magic’: what has happened to the inscribed names (distortion, confounding) would befall the targets themselves. The ritual analogy depended on the written tactility of the text for meaning.

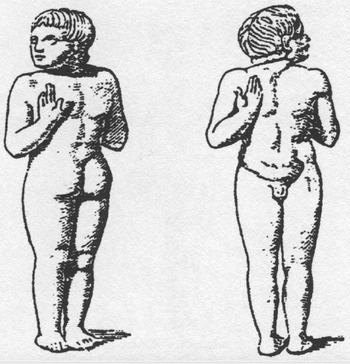

Textual distortion is found in another curse from the Malophoros sanctuary, CDS 24, on which eighteen names were written backwards (though individual characters face towards the right). There is little agreement among editors about the transcription of this difficult text, so scrambled are the names across and between lines.

CDS 24 (= SEG 16.571)

Selinous, Region of the Malophoros PrecinctFootnote 28

c.450 bce

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42566

Let there be utter destruction both of these men and of their kin! Nikullos the son of Kaposos, Dendilos the son of M <n>amon (?), Ainon the son of Blepon, Xenios the son of Apontis of the Herakleidai, Sauris, Athanis the son of Tammaros of the Herakleidai, Ras Pharmaua (?), Dion, Piakis, Pithias, Xaion, Mammaron(?), Zoita (?), Agathyllos the son of Xenios of the Herakleidai, Sunetos the son of Xenon.

My translation gives a general sense of the curse, but is insecure in several places.Footnote 29 Here the names of all victims were disfigured by the reversal of letters. Hence, in the first line of text, which otherwise runs from left to right, the name Νίκυλλος is written in reverse ΣΟΛΛΥΚΙΝ; in the second line, Καπόσο̄ is spelled ΟΣΟΠΑΚ, and so on. Just as the letters have been reversed and contorted in the lead, so too did the curse-writer intend for the victims to be confounded in life.Footnote 30 The textual play in CDS 24 and 25 – that is, the deliberate distortion of incised script – could only have evolved alongside the spread of writing, and written literacy, in early Selinous. The growing familiarity with written script surely catalysed this creative experimentation with textual distortion, and endowed written curses with still more ritual efficacy: the text itself could now hold meaningful power over the victims of the curse.

Figure 2. CDS 24, Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42566. Drawing from Gabrici (n. 15), fig. 183.

This engagement with the materiality of text can be seen in still another way in CDS 20 above (see figure 1), the discoid lead tablet targeting Selinontios, Timasos, and Tyranna. Four times the text employs the phrase ἀπεστραμ(μ)έναν ἐπ’ ἀτελείαι, ‘twisted back for the purpose of unfulfilment’ in regard to the victims’ tongues. Here the participle ἀπεστραμμένα expresses the goal of the curse: to ‘twist’ or ‘turn back’ the victims’ tongues, a means of confounding and incapacitating (ἐπ’ ἀτελείαι) an opponent's speech in court. This sentiment is underscored by the text's incision in a contorted, spiral shape on the verso; inscribing this curse required the physical twisting and turning of the lead disc, which mirrored the ‘twisting to unfulfilment’ of the targets’ tongues.

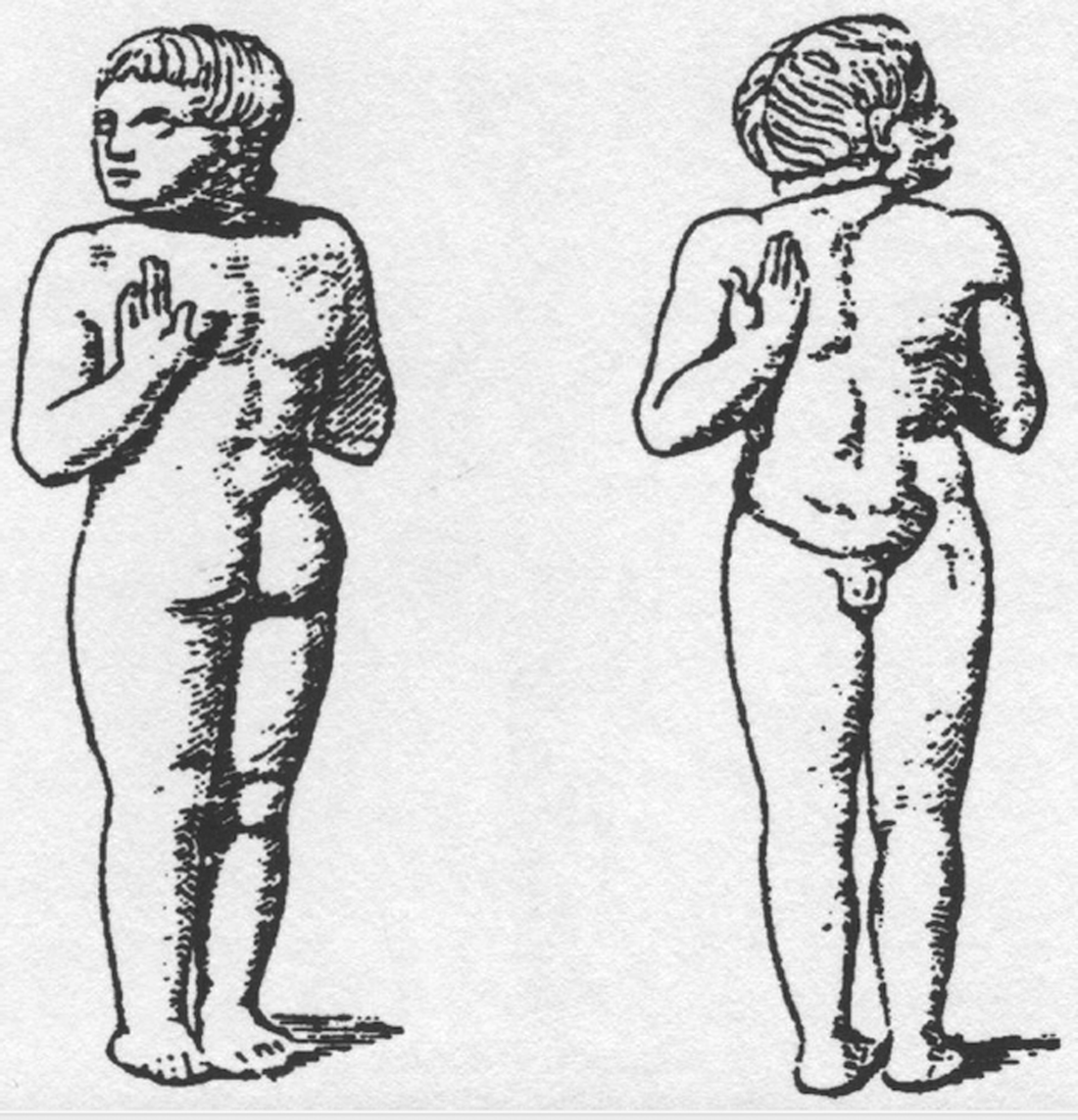

According to Faraone, the notion of twisting the tongue so that it cannot speak is a type of ‘distortive’ magic, which hinged upon the verb ἀποστρέφω. Faraone isolated groups of Greek incantations that aim ‘“to twist back” or “to distort” hostile human opponents or attacking demons and diseases’; this distortive principal is manifest in various media: amulets, curse effigies, and curse tablets.Footnote 31 It is evident in a bronze effigy from Kephalonia, the head and left arm of which have been ‘twisted back’ or ‘turned away’ (see figure 3); the doll embodies the notion of ‘twisting’ as a means of immobilizing or contorting an enemy. In CDS 20, the passive participle of the verb στρέφω (‘I twist’; ἀπεστραμ(μ)έν’ ἐπ’ ἀτελείαι) instead expressed this goal, which was materially realized by the incision of text in a contorted, spiral shape. Despite the tablet's early date, this marks a rather advanced stage of written literacy in Selinous, and an explicit awareness of the material properties of inscribed text. Like CDS 24 and 25, the Selinountine curses that invert and scramble the names of victims, CDS 20 uses the participial form of στρέφω with textual distortion – the twisting of script to mirror the twisting of tongues – in a self-consciously textual way (note, too, its use of ἐνγράφο̄ to curse victims).

Figure 3. Twisted bronze effigy from Kefalonia. Drawing from Melusine 9 (1898–9), 104, fig. 11.

One of the two new curse tablets published from Himera also exhibits textual distortion. The object dates to the first decades of the fifth century bce, and carries a list of personal names, many of which have the letters of the first syllable inverted.Footnote 32 Thus a male named Σιλανός is cursed on Side A in line 1, but his name is written ΙΣΛΑΝΟΣ; on Side B, Σίμος was inscribed as ΙΣΜΣΟ (line 5), with the characters in both syllables shuffled; and so on. All of these early Sicilian curses played with the characters of the written text: reversing, inverting, twisting, and deforming letters to analogically confound the target himself. The very shape and form of writing – the materiality of text – was drawn into the ritual process in a way that added significance to the text itself, beyond the semantic meaning of the words alone.

‘Scribal’ symbols and abbreviations

This written self-awareness can also be seen in the use of diacritical marks – what I broadly refer to as ‘scribal’ symbols, as they are suggestive of written competency – in some inscribed curses from 450 bce and earlier. These scribal signs include the analphabetic diple (from διπλῆ, ‘double’, referring to the two lines in the mark <), and the paragraphos, a horizontal punctuation often used to mark a textual division (—).Footnote 33 Abbreviations also appear in these texts. Early curse-writers betray a familiarity with textual conventions, and the use of such symbols within curse texts situates these objects within the realm of written literacy.

Let us first consider a curse tablet published by Bettarini in 2009, which emerged in Selinous’ Manuzza cemetery, the city's oldest necropolis.Footnote 34 The find marks another mortuary space in which early (c. 450 bce) curse tablets were deposited by residents of Selinous. The tablet is fragmentary, its text unremarkable; the use of a diple in the third fragment (Fragment C), however, deserves attention.

Bettarini (n. 13), 142

Selinous, Manuzza Necropolis

450 bceFootnote 35

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 45425

Fragment A Fragment B Fragment C

1 ..]ΛΟΣΣΑΙ[ 1 ]ο [Η]ύψ[ι- 1 -ΟΛΟΣΣ[. .]ΟΔΕ[

-το̄ [κ]αὶ Σελ̣ι̣[ν- ]ΟΣ[.]ΚΛ[ -ΣΣ< γλ[ōσ]σαν̣[

3 -συ̣κλέος[ 3 ]ιχα[.]ΟΡ[ vacat

-α[.]ρος καὶ [ ]ΑΣ[..]ΝΟΣ[

5 -ο Πυ̣ρρία καὶ [ 5 ]Μ[…]Τ̣ΑΣ[

]Ρ̣Ο[

This fragmentary curse allows few conclusions, but we can discern at least one reference to the ‘tongue’ in Fragment C.2, γλ[ōσ]σαν, and likely also in Fragment A.1, Γ]ΛΟΣΣΑΙ, amid several personal names: Πυρρία, Ηύψιος or Ηύψις, and perhaps Σōσικλε͂ς.Footnote 36 Among the peculiarities of this Manuzza tablet is the analphabetic sign (<), likely a diacritic added to the second line of Fragment C: ΣΣ< γλ[ōσ]σαν. This diple is often employed in the margins of a text to draw attention to something therein. Yet in this curse text, the symbol is preceded by a double sigma (ΣΣ<), and followed by the full word γλōσσαν. Here the sign probably indicates an abbreviation. Bettarini suggests that the scribe noticed the forthcoming lack of space in the row, and proceeded to abbreviate a word with this symbol.Footnote 37 The diple symbol appears in still older curses from Selinous, such as CDS 26 from the city's western Gaggera Hill.

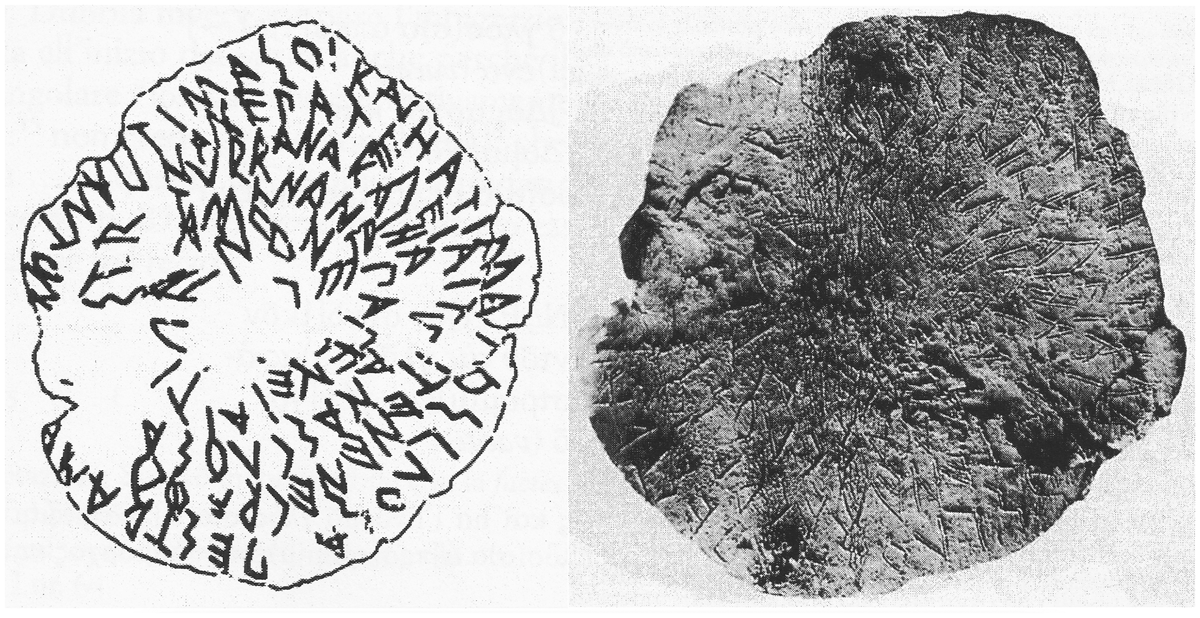

CDS 26 (= SGD 101)

Selinous, Region of the Malophoros PrecinctFootnote 38

500–450 bce

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42564

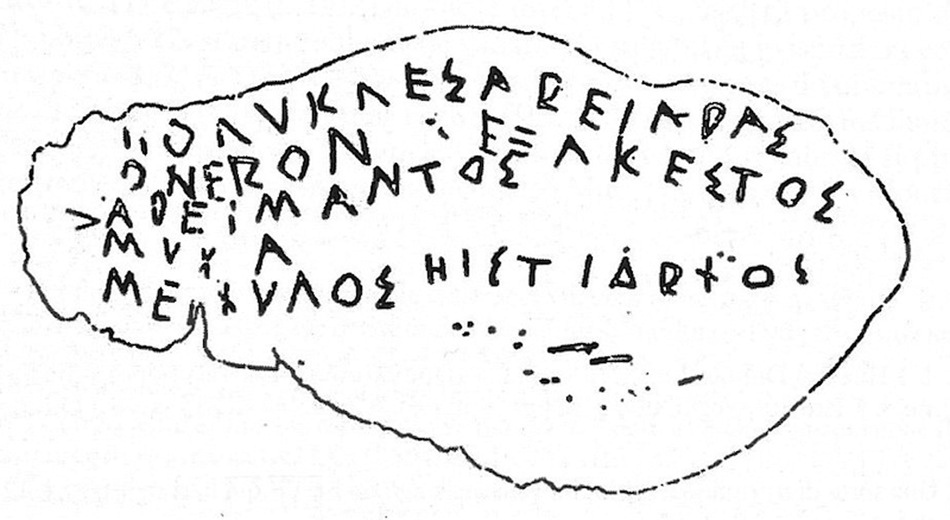

1 Πολυκλε͂ς Ἀρειάδας

Ὀνέρο̄ν Ἐξάκεστος

3 > Ἀδείμαντος

Μύχα

5 Μειχύλος ℎιστίαρχος

Figure 4. CDS 26, Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo, inv. no. 42564. Drawing from Gabrici (n. 15), fig. 184.

Polykles, Areiadas, Oneiron, Exakestos, >Adeimantos, Mycha, Meichylos, Histiarchos.

Here we encounter a simple list of named individuals, all of whom were targeted by the curse. Of interest again is the diple sign in line 3 (>), the same symbol found in the Manuzza curse (though inverted). Inserted into the otherwise vacant margin beside the name Adeimantos, here the diacritic appears to emphasize that name, and perhaps he was the main litigant.Footnote 39 Does the use of these textual signs and annotations – a marker of advanced written competency, however they are interpreted – signal the presence of professional curse-writers, or persons otherwise fluent in the inscription of text? I think so.Footnote 40

A contemporary tablet from Selinous’ Gaggera Hill raises these same questions with its skilful use of abbreviations. Dating to the first half of the fifth century, CDS 27 (= SGD 103) comprises a column of fifteen names, thirteen of which were abbreviated; these thirteen names were shortened even though sufficient space remained to write out the names in full.Footnote 41 Thus we find Ηυψ- for Ηύψις, Ηερακλ- for Ηερακλείδας, and Ηιστια- for Ηιστίαρχος. Apart from inventories and catalogues, such abbreviations are rare in Greek inscriptions.Footnote 42 Does the use of abbreviations here, in an early to mid-fifth-century Sicilian curse, suggest the influence of official public documents – legal, financial, or otherwise? It seems probable, and may also ground the object in a legal context, as it betrays a familiarity with formal written conventions.

Finally, other Sicilian curse tablets make use of the paragraphos, a horizontal ‘dash’ inserted within a row of text – though these emerge primarily in tablets from Kamarina's Passo Marinaro cemetery on the southern coast of Sicily, and begin only in the mid-late fifth century bce.Footnote 43 At least four tablets from Kamarina employ paragraphoi (Curbera [n. 13], nos. 3–4, 8, 10), which seemingly mark-off conceptual sections of texts; two of these curse tablets were deposited in graves during the fifth century bce (nos. 3–4), while two were composed in the fourth century bce (nos. 8 and 10). All of these paragraphoi curses comprise lists of personal names; the fourth (no. 10 = SEG 47.1439) is a bit more complex, listing the names of several individuals (Δεινίας, Πολλίας, etc.), and concluding with the phrase ἐξόλης οἵ (‘Destroyed, these men!’).Footnote 44

The use of diacritical marks like the paragraphos and diple, in addition to textual abbreviations, suggests that some early curse-writers were fluent in the conventions of textual composition. Texts bearing such symbols surely developed within the written realm. It seems likely that some of these tablets were produced by professional scribes, who were inscribing a wide variety of texts on lead in Selinous during the late sixth and fifth centuries bce, many of which were ritual in nature (did they ‘moonlight’, to borrow a term of David Jordan's, as private curse-writers?)Footnote 45 The involvement of scribal professionals in Sicilian curse-writing may further explain why the ritual bears a strong written focus in its earliest years.

Lists of names

The final group of early Greek curse tablets that appear self-consciously textual in nature are those that carry lists of personal names, especially names arrayed in columnar formats. At least some of these private curses may have drawn upon legal/civic lists or registers of named individuals, which were written down and publicly displayed within the late archaic polis. In Selinous and elsewhere, these early curses probably drew inspiration from written visual culture displayed in public. Consider CDS 18 from Selinous’ Buffa necropolis, dating to the earlier fifth century.

CDS 18 (= SEG 26.1114)

Selinous, Buffa NecropolisFootnote 46

500–450 bce

Antonino Salinas Regional Archaeological Museum, Palermo

1 Kulika

Xenokles

Glaukias

Here we encounter a simple list of names, a well-attested curse type by the early to mid-fifth century.Footnote 47 Lists of individual names were incised upon lead, and so ‘targeted’ by the curse, in two different formats: names could be inscribed continuously, appearing in succession like standard script; or names could be listed in columns. CDS 18 makes use of the latter, columnar name list, and provides no further information about the targets. Still more striking is CDS 14, which likely also comes from Selinous (along with the rest of this cache, acquired en masse by the Martin-von-Wagner Museum in Würzburg).

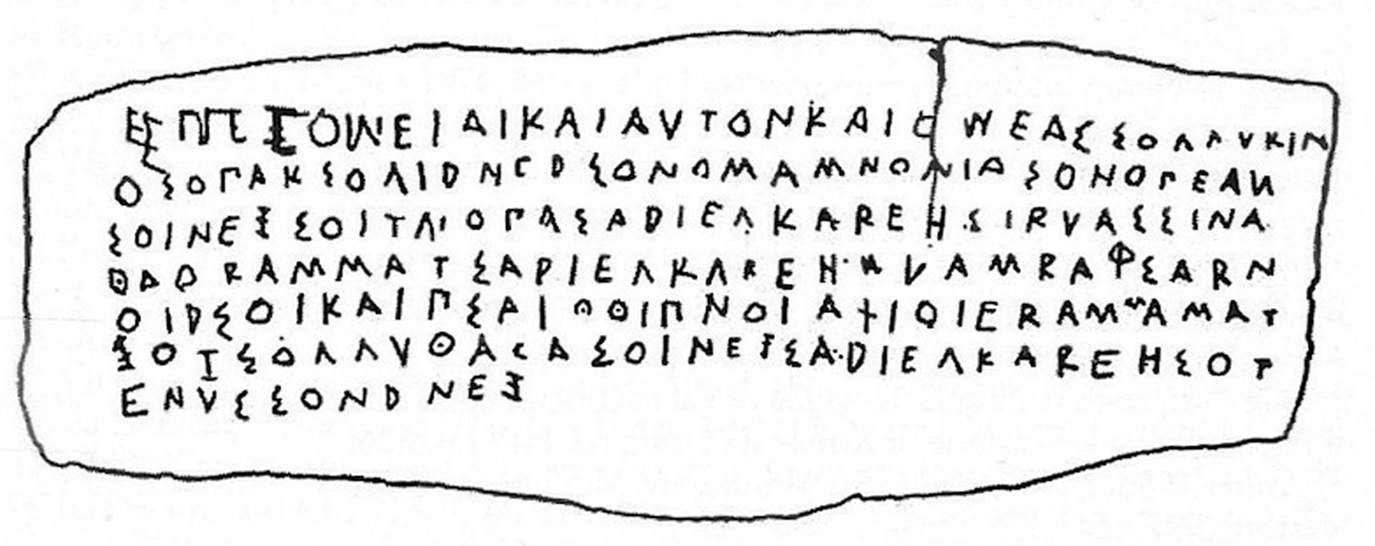

CDS 14 (= SEG 39.1021)

Selinous, provenance unknownFootnote 48

500–400 bce

Würzburg, Martin-von-Wagner Museum, inv. no. K2099

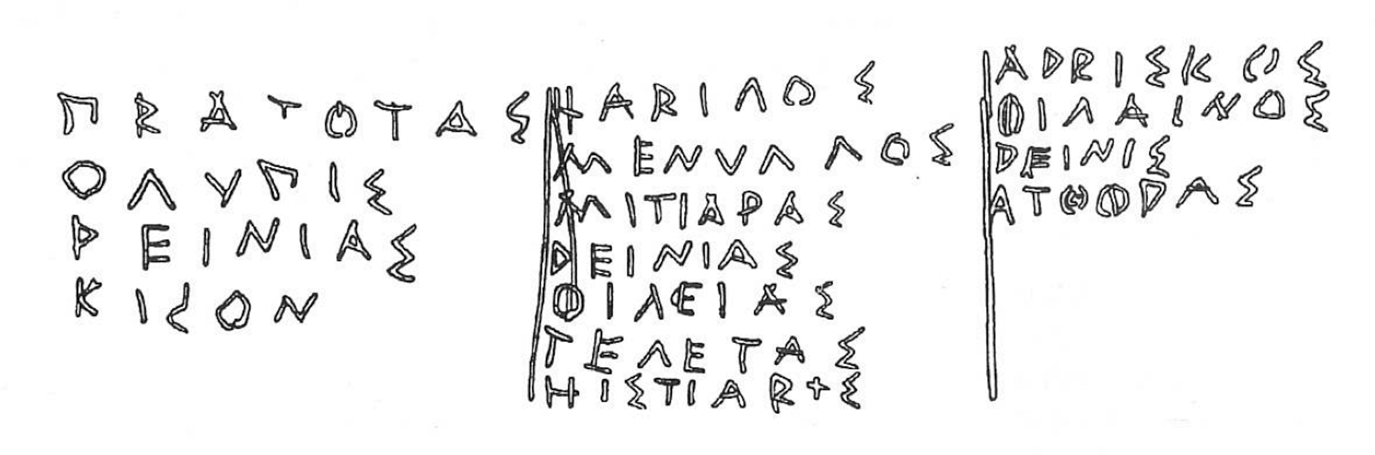

Col. A Col. B Col. C

1 Πρατοτᾶς 1 Χάριλος 1 Ἀ<ν>δρίσκος

Ὄλυ<ν>πις Μένυλλος Φίλαινος

3 Δεινίας 3 Μιτιάδας 3 Δεῖνις

Κίβ̣ο̄ν Δεινίας Ἀτ․ο̣δας.

5 Φιλείας

Τελέτας

7 ℎιστίαρχ<ο>ς

This curse was organized into three symmetric columns of text. Inscribed vertical lines divide the columns, each of which carries lists of individual names. The first column contains four names, the second seven, and the third another four. Each name is rigidly separated from those around it, and the stark text resists additional details – conjunctions, verbs, and patronymics are absent. What the curse sacrifices in commentary it gains in visual effect, drawing focus to each individual name in turn. The pillared arrangement of text was deliberate, underscored by the incision of vertical lines to delineate the columnar lists.

Figure 5. CDS 14, Würzburg, Martin-von-Wagner Museum, inv. no. K2099. Drawing from Curbera (n. 13), 166.

Curbera has suggested that such inscribed name lists drew upon written public documents. He notes that late archaic poleis such as Selinous likely published official name lists on whitewashed tables or plastered walls/boards, and that these civic rosters were visually prominent within the city's public spaces.Footnote 49 It is possible that private curses were influenced by these public texts, and adopted the format (and perhaps also some abbreviations) from name registries. Drawing on Thomas’ work on literacy, Gordon has also studied the function of such name lists within Greek curse tablets.Footnote 50 He too suggests that public lists – that is, lists in which individual names were recorded and publicly displayed in columnar formats – came to influence the physical layout of private curse tablets, and he argues that the power of these columnar curses resides in the agency of public lists in the ancient city. From the sixth to the fourth century bce in Athens, such lists included deme registries, with names of male citizens and (later) metics, public lists of military deserters, lists of homicides and would-be tyrants, cavalry lists, and lists of public debtors.Footnote 51 Similar sorts of public lists were likely also present in Selinous and Himera by the late sixth century bce.Footnote 52 Gordon suggests that the use of the columnar list in curse tablets demonstrates how curse-writers could harness symbols of (often negative) civic authority to create a powerful private curse:

The columnar list is an example of magical practice usurping tokens of authority in the dominant world for its own ends. The public list of infamy singled out each name as a separate object of inspection, opened to scorn and derision; the private list drew upon that public model as a source of guidance to the powers of the Underworld, who were invited to react as the Athenian public reacted. More precisely, perhaps, the private columnar list sought to evoke the public process of exposure and condemnation that prefaced the appearance of a name on these lists of infamy.Footnote 53

The emergence of name lists in early Greek curse tablets, especially lists neatly arrayed in columnar fashion, surely drew influence from written civic documents displayed in the public realm. These, too, conform to late archaic written habits. The arrangement of characters into columns is in itself a reflection of textual trends, with no obvious relation to older oral traditions.Footnote 54 The law courts were obvious sites in which name lists would have been concentrated in this period; it seems possible that curse-writers could easily have copied victims’ names from legal documents or even whitewashed boards in the preparations leading up to a trial.

Conclusions

Dating from the late sixth century bce, many of the oldest Greek curse tablets emerge as self-consciously written texts, which did not serve to record the spoken word. The majority were avowedly textual in nature, and quite possibly developed in tandem with the spreading use of writing in litigation at Selinous and probably also Himera. Most of these texts were unconcerned with the recording of speech, and bear few traces of orality. The oldest carry only prose texts, and show detachment from orality in their use of verbs of ‘writing’ to curse opponents (forms of γράφω and compounds). They also exhibit textual distortion, scribal symbols/abbreviations, and columnar lists of names, all of which evolved within the written realm. These represent a later stage in the development of written literacy – what Thomas and others have described as a ‘third-person notice of information’. These texts were conveying information to chthonic powers and the dead, and effecting and memorializing a ritual act.

At their inception, the majority of these texts do not appear to have represented statements that were meant to be spoken; here writing did not work in the service of speech, or provide a way of communicating what would otherwise have been spoken aloud. In this sense, the oldest Greek curse tablets recall earlier instantiations of Greek writing that operated fully independently of the spoken word. In archaic Athens, for example, the verb γράφειν (‘to write’) and the repetition of the first few letters of the alphabet appear in early Attic vase inscriptions; these rough scribbles proudly displayed the acquired skill of writing.Footnote 55 Parallels can also be seen in early votive dedications to Zeus Semios on Mount Hymettos in Attica. Incised on ceramic sherds beginning in the seventh century bce, these graffiti also ‘proclaim’ their written nature: they are self-consciously textual dedications, comprising abecedaria, names with verbs of writing (for example, ἔγραφσε, so-and-so ‘wrote this’), and even individual letters. It seems as though the written word itself was deemed an appropriate dedication within this cult; these text-centric votives may have appealed directly to Zeus Semios or Zeus of the ‘signs’ as written symbols in and of themselves.Footnote 56

Why do the majority of early Sicilian curse tablets reveal this written self-awareness? Quite possibly the use of writing in these private ritual texts ensured permanence – immortality, even – through the physicality of the text. Curses were thus perpetual and immutable, and did not depend upon the presence of the composer (as reciter) to have lasting effect. By this time, the polis was also developing new institutional uses for written text, which continuously evolved in response to opportunities afforded by the technology of writing. The earliest Selinountine curse tablets appear to have engaged with the city's law courts, and may have developed alongside or in response to the spread of written legal procedure. The legal process itself – that is, the gathering of witnesses, the collection and relaying of testimonies, and so on – was evolving alongside the spread of writing, and curse tablets may be understood as ritual participants in the written ‘revolution’ of the sixth-century law courts. Indeed, it may be in connection with the new use of writing in legal and judicial procedure that inscribed curse tablets first appear at Selinous. I suggest, in other words, that the earliest curse tablets developed under the umbrella of written legal procedure.

Professional scribes may also have had some role in this transition. Officials called mnemones (‘remembrancers’) played a part in the shift from oral to written law in many early poleis, and are thought to have been responsible for remembering oral law and judicial cases prior to the advent of public writing. After writing became established in these communities, and was employed for public record, Thomas notes that many of these mnemones ‘end up as scribes’.Footnote 57 In Selinous, Himera, Kamarina, and other coastal Sicilian poleis, might such scribes have helped in the transition from an oral to a written legal process? This could explain some of the agents responsible for the ritual texts examined above, especially those that employ diacritics, abbreviations, and ‘scribal symbols’, as I have referred to them here. The oldest Greek curse tablets from western Sicily thus reflect the proliferation of writing in the law courts and, in their earliest instantiations, appear self-consciously textual (rather than oral) in nature.