In April 2016, the UN General Assembly declared the next 10 years as a decade of Action on Nutrition around the world( 1 ). In the African context, this declaration is even more pertinent considering the current unacceptably high burden of malnutrition and the relatively slow pace in the decline of malnutrition on the continent. Presently, an estimated 220 million people on the African continent are energy-deficient( Reference Covic and Hendricks 2 ). In addition, micronutrient malnutrition remains widespread and affects the most vulnerable( Reference Covic and Hendricks 2 ). More than 165 million children and women of reproductive age are anaemic( 3 ); the burden of anaemia is pervasive and excessively prevalent in all but two African countries. Almost 60 million African children under 5 years are stunted( 4 ). Concurrently, obesity and overweight are increasing across the continent with more than one quarter of the global burden of overweight/obesity in preschool age children occurring in Africa( 4 ).

In many African countries, the burden of malnutrition is multi-faceted. For example, in thirteen countries, health and nutrition authorities are struggling to deal with a triple challenge of malnutrition: unacceptably high rates of childhood stunting, anaemia and overweight( Reference Haddad, Bendech, Bhatia, Covic and Hendricks 5 ). These different forms of malnutrition place huge social and economic costs on society. Some estimates indicate that annual costs of undernutrition range between 3 and 16 % of Gross Domestic Product( Reference Hoddinott 6 ). If low- and middle-income countries take no action on non-communicable diseases, cumulative costs are estimated to reach $7 trillion between 2011 and 2025( 7 ).

The present paper reviews existing published and grey literature and discusses the need for building capacity, academic research networks and promoting evidence-informed decision making (EIDM) to address malnutrition in Africa. The paper expands on a chapter presented in the 2015 Annual trends and Outlook Report( Reference Holdsworth, Aryeetey, Jerling, Covic and Hendricks 8 ) of ReSAKSS Africa. It also draws upon a symposium entitled ‘Evidence-informed decision making for nutrition: African experiences and way forward’, which was presented at the 2016 African Nutrition Epidemiology Conference to highlight EIDM. The paper concludes by sharing lessons learnt from existing EIDM initiatives in Africa with the view to diffuse EIDM in policy and programme planning to address malnutrition and disease burden across the continent.

Research and policy landscape in Africa

A key component in addressing malnutrition is the use of high quality evidence by decision makers( Reference Lokosang, Osei, Covic, Covic and Hendricks 9 ). Evidence-informed nutrition policies and research programmes, when introduced on a national scale and appropriately prioritised, have the potential to encourage delivery of improved nutrition services, and contribute to sustainable development outcomes( Reference Gillespie, Haddad and Mannar 10 , Reference Bryce, Coitinho and Darnton-Hill 11 ). The enhancement of EIDM and policy-driven nutrition research in resource-limited settings is thus increasingly recognised as essential for maximising public health benefits and resources( Reference Ioannidis, Greenland and Hlatky 12 ). Implemented appropriately, EIDM is likely to translate quality evidence into action and enhance impact, particularly in the world's poorest settings( 13 ).

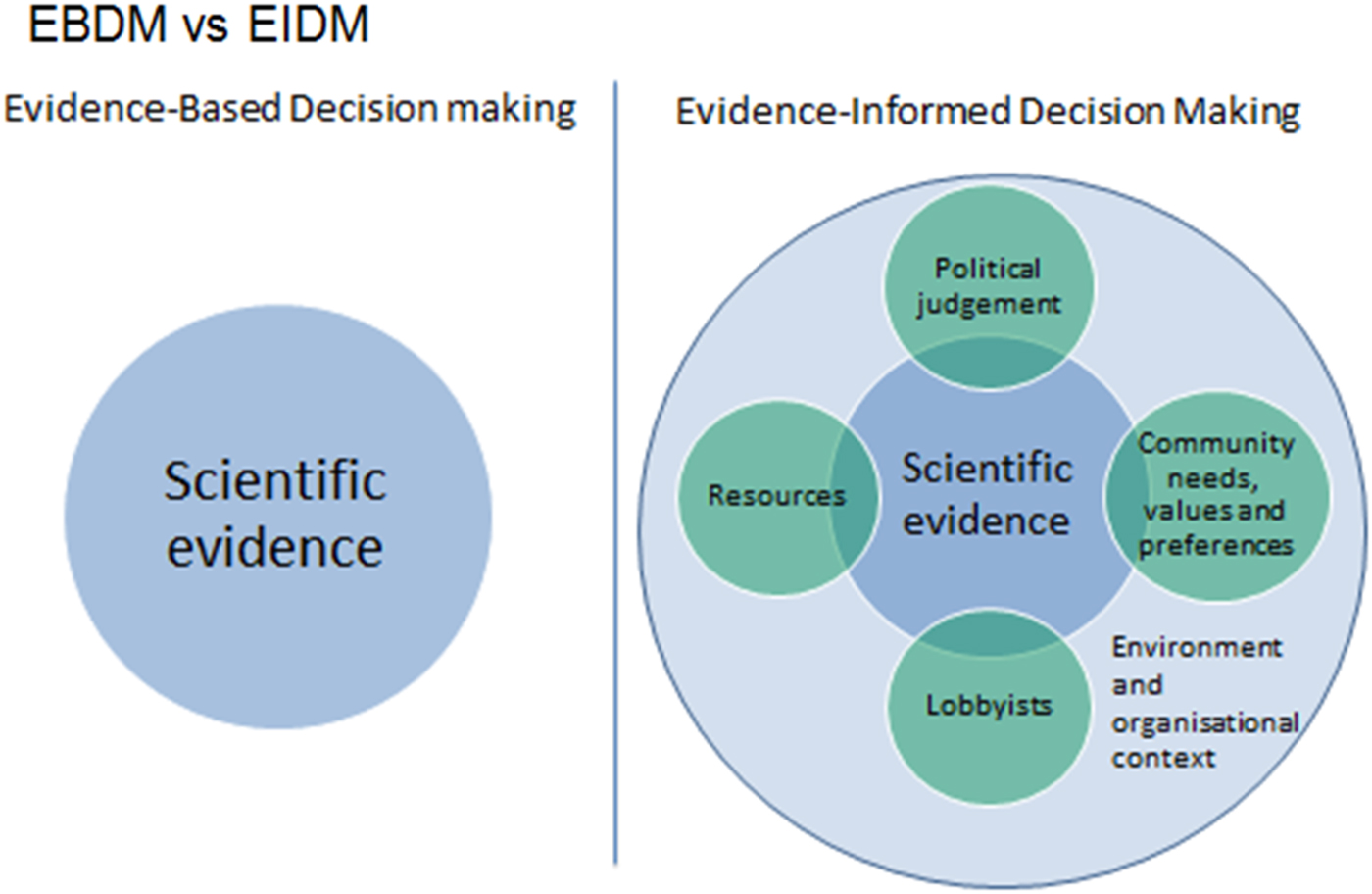

A critical and practical aspect of applying EIDM is the conceptualisation of what constitutes evidence (Fig. 1)( Reference Satterfield, Spring and Brownson 14 ). The Health Evidence Network defines evidence as ‘findings from research and other knowledge that may serve as a useful basis for decision making in public health and health care’( Reference Lomas, Culyer and McCutcheon 15 ). This definition aptly captures key factors that influence decision making beyond research findings. Such factors include levels of experience, existing public health resources, knowledge about community nutrition and health challenges, community preferences and needs, and the political climate( Reference Yost, Dobbins and Traynor 16 , 17 ).

Fig. 1. Conceptualisation of evidence informed v. evidence-based. Adapted from Satterfield et al ( Reference Satterfield, Spring and Brownson 14 ).

It is known, however, that harnessing the power of research evidence for decision making in nutrition is limited by multiple factors in Africa and other low resource settings. Firstly, although a relatively large volume of published nutrition research exists in Africa, this research is mainly descriptive with insufficient intervention-related evidence to support policy development( Reference Lachat, Roberfroid and Van den Broeck 18 ). Secondly, existing research evidence may not adequately address the priorities of national and local contexts( Reference Morris, Cogill and Uauy 19 – Reference Verstraeten, Roberfroid and Lachat 21 ) and particularly, the needs of low- and middle-income countries( Reference Resnick, Babu and Haggblade 22 ). Even where they exist, insufficient effort is invested in championing use of existing nutrition research by policy makers( Reference Gillespie, Hodge and Yosef 23 ). This lack of visibility of evidence can prevent uptake of the existing research evidence.

Other systemic challenges to evidence use have been identified. In an analysis of barriers towards sustainable nutrition research, African researchers identified unmet need for developing and conducting research that meets quality demands from high-impact journals. This is partly because of inadequate resources and funding needed to design and implement long-term follow-up or experimental studies with sufficient statistical power. Much of the existing research in Africa is typically supported by ad hoc funding and collaborations with non-African researchers and donors. Capacity to take stock of existing literature and research proposals that address pertinent knowledge gaps and policy demands were considered essential to support the local research agenda( Reference Lachat, Roberfoid and van den Broeck 24 ).

Although not limited to Africa, it is also known that many nutrition studies are electronically locked behind journal paywalls and thus remain inaccessible, particularly to decision makers. Also, a significant proportion of local research in Africa is published in Africa-based journals or shared as grey literature, which is not indexed in high visibility databases and therefore difficult to access. Conversely, the existing research outputs remain inaccessible to most decision makers largely because scientists tend to promote their work to academic audiences, effectively leaving out the decision makers who need the evidence for decision making. In some cases, accessible research may be limited by biases linked with poor study design and poor reporting of findings( Reference King 25 , Reference Horton 26 ).

As a result, decisions to address malnutrition may either be unsupported by relevant evidence( Reference Gillespie, Hodge and Yosef 23 , Reference Lachat, Roberfoid and van den Broeck 24 ), or are based on poor-quality evidence. In situations where there is insufficient time, resources or capacity to generate quality evidence, decision makers are left with no choice but to use anecdotal evidence to support decisions. Such evidence, however, ranks low on the evidence-appraisal scale and is thus likely to result in low-impact interventions and a waste of scarce resources.

Evidence-informed decision making: response to accelerating progress in reducing malnutrition burden in Africa

Working with a range of diverse actors, new efforts are therefore needed in Africa to foster EIDM to address the malnutrition burden. The availability of high-quality evidence is necessary, but insufficient by itself in decision-making processes. A culture of information stewardship and long-term commitment needs to be fostered within the nutrition research community. Evidence synthesis tools, such as evidence maps, systematic reviews and rapid reviews, are useful and enable policy makers to make informed decisions on which policies to invest in. These tools further enable academia to harness the available evidence. In addition, capacity in implementing health technology assessments is critical in learning about the properties, effects and/or impacts of health technologies and interventions. Evidence synthesis and technology assessments should, however, be tailored to identify and prioritise needs, by addressing locally relevant questions, to reduce the risk of epidemiological research waste.

Before evidence can be translated into action (such as policy, programmes, or decisions), other factors such as economic constraints, advocacy, community preferences, traditions and values must be considered. Using evidence to inform decisions therefore requires leadership, capacity and concerted action( Reference Resnick, Babu and Haggblade 22 ). Both technical capacity and leadership are critical( Reference Gillespie, Hodge and Yosef 23 ) for harnessing the use of evidence to inform policies and programmes, and therefore better decisions. Such capacity and leadership skills are required at all stages of the stepwise EIDM process: from articulating demand, generating data, conducting evidence synthesis and mobilising knowledge from multi-sectoral research to translating knowledge from research to the local context. This does not only involve strengthening individual capacity but also necessitates building operational and institutional capacity (for example researchers) and increasing the sustainability and resilience of the systematic evidence-informed processes and partners.

The African Nutrition Leadership Programme is a model of how to develop individual functional leadership capacity in Africa( Reference Taljaard 27 ). In addition, leadership for nutrition within all government agencies (such as agriculture, water and sanitation, and social protection), civil society, the UN, academia, bilateral donors and the private sector is recognised as a fundamental aspect of translating evidence of the effectiveness of multi-sectoral nutrition programmes and policies into action on the ground. A number of initiatives are presently ongoing that seek to strengthen capacity for enhancing technical competence in nutrition in Africa( Reference Aryeetey and Lartey 28 ) including re-entry grants by the International Union of Nutritional Sciences; the eNutrition Academy platform for eLearning, creating access to high quality evidence through Hinari, and Agora, EnLink Library and North-South research collaboration that includes capacity development components( Reference Aryeetey and Lartey 28 , Reference Geissler, Amuna and Kattelmann 29 ).

Multiple EIDM initiatives have been identified in Africa (see Box 1 for a brief overview). Evidence Informed Decision Making in Nutrition and Health (EVIDENT) is a relatively new initiative that has attempted to follow a stepwise EIDM process. The Scaling Up Nutrition movement also uses a similar approach of engaging stakeholders and to using existing evidence-base( 30 ). EIDM initiatives that promote leadership, include Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia and Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in East Africa, both of which operate as part of the CGIAR Agriculture for Nutrition and Health Program. All these initiatives demonstrate promising solutions for addressing the identified challenges, and could have huge impact when scaled up.

Box. 1 Evidence-informed decision-making initiatives in Africa

Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH): A Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research Programme focused on linkages between agriculture, nutrition and health. www.a4nh.cgiar.org/

African Evidence Network: A network of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers promoting evidence production and use in decision making. For education, health and technology. www.africaevidencenetwork.org/about-us/

Cochrane Nutrition Field South Africa: Based in South Africa and seeks to increase coverage, quality and relevance of Cochrane nutrition reviews. http://cwww.cochrane.org/news/cochrane-nutrition-field-established-south-africa

Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence (BCURE): Promotes and builds capacity in EIDM in developing countries. bcureglobal.wordpress.com/

Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in East Africa (LANEA): An international research consortia on leveraging agriculture and food policies and interventions to nutrition. www.fao.org/3/a-i4550e.pdf

Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE): A collaborative project to strengthen of EIDM capacity and partnerships in Africa. www.who.int/evidence/sure/en/

The SECURE Health Programme: An initiative of the African Institute for Development Policy to improve and optimise individual and institutional capacity in accessing and using data and research evidence in decision making for health. www.afidep.org/?p=1364

VakaYiko Consortium: A programme of the International Network for the Availability of Scientific Publications. Aims to build capacity and create an enabling environment for EIDM www.inasp.info/en/work/vakayiko/

The collaboration for Evidence Informed Decision Making in Nutrition and Health

EVIDENT is an international collaboration, which aims to strengthen the capacity to address the disparity between research activities and local evidence needs in nutrition and health in Africa. Hence, EVIDENT aims to bridge the gap between academic research and nutrition policies and programmes. Unlike other initiatives that aim to improve the use of evidence in decision making in health, EVIDENT focuses primarily on nutrition. EVIDENT, therefore, encompasses all issues that are at the forefront of global nutrition and health policy, and highly relevant to Africa, focusing on stunting, infant and young child feeding, maternal and child health, micronutrient deficiencies, obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases.

The EVIDENT approach is to provide evidence that is tailored to the expressed needs of decision makers. EVIDENT aims to increase impact by strengthening this evidence-policy pathway and also by translating local needs into recommendations that are specific, actionable and informed by the best available evidence, with recognition of stakeholder priorities.

Through activities within each pillar, EVIDENT investigates if such a stepwise process for identifying and using evidence actually leads to better decision making and better nutrition policies in countries with a high burden of malnutrition in all its forms. EVIDENT also explores how best to conceptually represent these processes of evidence application across different countries: i.e. whether this a priori framework applies in a linear way as proposed in Fig. 2, or whether it is a more iterative process.

Fig. 2. Evidence informed decision making in nutrition and health (EVIDENT) conceptual framework for evidence-informed decision making. Source: The EVIDENT Partnership (http://www.evident-network.org/) and Holdsworth et al ( Reference Holdsworth, Aryeetey, Jerling, Covic and Hendricks 8 ).

Activities in African countries

In the past 3 years, EVIDENT has implemented numerous activities in four case countries in Africa, of which three are described here: Benin, Ghana and South Africa (Fig. 3). Although the case study activities have been designed to address needs relevant to each country's context, common strands emerge across countries. These include the process for engaging with key stakeholders in nutrition to understand the present process for decision making, the key players who influence nutrition programming and the process for prioritisation of nutrition actions. These case studies were designed to be conducted alongside a rapid stakeholder mapping exercise. Overall, the learning activities were carried out in consultation with the relevant nutrition departments or agencies of the case study countries. In addition to the case studies, key personnel in academia and programme implementing Government Departments have been trained on aspects of EIDM, including evidence synthesis, cost-effectiveness and contextualisation of evidence.

Fig. 3. (Colour online) Case study activities in Benin, Ghana and South Africa.

In all three countries, the case studies focused on identifying who the key stakeholders were in nutrition policy and programme implementation. Similar tools were utilised in the process of stakeholder influence mapping: Net-Mapping in Ghana( Reference Schiffer and Waale 31 ), Mind Mapping in Benin and Power to Influence Matrix in South Africa( 32 ). In all countries, it was clear that a wide variety of partners were involved in nutrition policy and programming in addition to Government agencies. These included UN agencies, civil society actors (both international and indigenous), research and academia, and the media. Nevertheless, the roles and influence of various stakeholders are not always the same across countries.

Also in all countries, key informant interviews were undertaken with high level officials of multi-stakeholder organisations (exception: only government sector in South Africa) were utilised. In addition, a desk review in Ghana was used to explore the process for nutrition policy and programme prioritisation and decision-making processes as well as the process for EIDM in nutrition. Furthermore, priority questions for nutrition were identified within countries for which three relevant systematic reviews are currently underway (PROSPERO registrations: Benin: CRD42016035941; Ghana: CRD4201037471; South-Africa: CRD42016038451). All countries have conducted a dissemination process in which stakeholders were engaged to discuss findings of the case study. From these case studies, it emerged that policies are driven by evidence generated both within and outside a country (e.g. UN Agencies, bilateral donor agencies). However, application of evidence was moderated by multiple factors including political will, influential international agencies, personal interests of decision makers, availability of local evidence and funding. It also became clear that the defined a priori framework differed across countries, and may not apply in a linear way as has been proposed in Fig. 2.

Lessons learnt in the Evidence Informed Decision Making in Nutrition and Health network across countries

Experiences from the case studies have shown that using evidence to inform decision making is neither cheap nor easy, but it has major advantages. The ten key lessons learnt from this process are summarised in Table 1 later:

Table 1. Lessons learnt while implementing evidence-informed decision making (EIDM) case studies in Benin, Ghana and South Africa( Reference Holdsworth, Aryeetey, Jerling, Covic and Hendricks 8 )

EVIDENT, Evidence informed decision making in nutrition and health

Altogether, experiences from the EVIDENT activities demonstrate some key aspects of what is required to fill the gap for EIDM in Africa. Going into the future, EIDM initiatives need to cultivate leadership and capacity within and across countries. In the example of EVIDENT, this leadership emerged from academia. In practice, it has become clear that there is still more work to be done to bring academics into a common space with decision makers and implementers. When appropriately cultivated, this leadership will be useful to generate and sustain needed partnerships and harness available resources for generating, appraising, contextualising and championing evidence for decision-making and prioritisation in nutrition.

On various platforms where the experiences of EVIDENT have been shared, there has been a positive response to the achievements made. In addition, EVIDENT has been urged to share the experiences and lessons learnt more widely in order to engender interest and uptake in other settings. A key challenge however remains how to sustain the momentum generated. One of the proposed means is to partner with established initiatives like the Scaling Up Nutrition movement and the Agriculture, Nutrition & Health academy. This way, more stakeholders and also with a varied background can be reached to sustain activities. In addition, mainstreaming of the EIDM approaches through pre-service training can build capacity as part of higher education training.

Methodological advances

Access to information is a key enabler of informed decision making. Although progress has been made in facilitating access to academic publications in low- and middle-income countries, practical constraints such as poor internet connectivity and language barriers persist. Although international consensus favours the need to make published research evidence and data accessible, much data intended for sharing remains isolated, and stored in formats that restrict reuse( Reference Wilkinson, Dumontier and Aalbersberg 33 ). One initiative, which indirectly resulted from EVIDENT, to improve usefulness of nutrition research, is the development of reporting guidelines for nutrition research known as STROBE-nut( Reference Lachat, Hawwash and Ocke 34 ). STROBE-nut provides a set of twenty-four items to consider when reporting research regarding nutritional epidemiology and dietary assessment, with the aim to increase completeness and interpretation of nutrition research and thereby to strengthen the quality of the evidence base.

Conclusion

The emergence of EIDM initiatives on the African continent is an indication of the growing demand by decision makers at different levels for high quality evidence to inform decision making. The case studies in three different African countries presented here revealed strong interest for partnership between researchers and decision makers. However, there is need to cultivate, nurture and strengthen the linkages to accelerate progress in reducing the malnutrition burden in Africa. The existence of networks like EVIDENT and other similar EIDM initiatives can support the development of both capacity and leadership, EIDM processes and the necessary partnerships. The growth of EIDM, however, needs to be championed actively by both researchers and decision makers and supported at regional, national and international level.

Acknowledgement

The EVIDENT Network appreciates the time and effort of all stakeholders at global and national levels to participate in the stakeholder consultations.

Financial Support

This research received a grant from the Development Cooperation of Belgium (#912502) (http://diplomatie.belgium.be/en/policy/development_cooperation/) and Nutrition Third World (www.nutrition-ntw.org).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Authorship

R. A. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.